Abstract

Corynebacterium glutamicum is known for its effective excretion of amino acids under particular metabolic conditions. Concomitant activities of uptake and excretion systems would create an energy-wasting futile cycle; amino acid export systems are therefore tightly regulated. We have used a DNA microarray approach to identify genes for membrane proteins which are overexpressed under conditions of elevated cytoplasmic concentrations of methionine. One of these genes was brnF, coding for the larger subunit of BrnFE, a previously identified two-component isoleucine export system. By deletion, complementation, and overexpression of the brnFE genes in a C. glutamicum strain, in which the two uptake systems for methionine were inactivated, we identified BrnFE as being responsible for methionine export. In the presence of both substrates in the cytoplasm, BrnFE was found to transport isoleucine and methionine at similar rates. The expression of the brnFE gene cluster depends on an Lrp-type transcription factor and was shown to be strongly induced by increasing cytoplasmic methionine concentration. Methionine was a better inducer than isoleucine, indicating that methionine rather than isoleucine might be the native substrate of BrnFE. When the synthesis of BrnFE was blocked by chloramphenicol, fast methionine export was still observed, but only at greatly increased cytoplasmic levels of this amino acid. This indicates the presence of at least one other methionine export system, presumably with low affinity but high capacity. Under conditions where cytoplasmic methionine does not exceed a concentration of 50 mM, BrnFE is the dominant export system for this amino acid.

It is now well established that transport proteins in the cytoplasmic membranes of bacteria are responsible not only for uptake of nutrients such as amino acids but also for their export (6, 9, 10, 18, 19, 20). In the last 15 years, export systems in Corynebacterium glutamicum and in Escherichia coli have been characterized in biochemical and in molecular terms for a number of amino acids, namely, l-glutamate, l-lysine, l-threonine, l-isoleucine, l-arginine, l-cysteine, and cysteine derivatives (20). The first three amino acids listed above are bulk products in biotechnology, and are all produced by fermentative processes using C. glutamicum or E. coli. Another bulk product is dl-methionine, which is produced by a chemical process (21), although attempts to develop fermentative processes have been reported (1, 16, 26). Unlike the other amino acids, methionine can be applied in racemic form as a feed additive, since mammals harbor a methionine racemase. It is nevertheless interesting to investigate the possibility of a microorganism-based technology for the production of l-methionine, which would have advantages compared to the racemate, e.g., in terms of optimization of nutrient utilization. Production of l-methionine requires the presence of an appropriate excretion system; however, export systems for this amino acid have not been reported so far.

Amino acid exporters in C. glutamicum are likely to counteract situations of metabolic imbalance. These situations either may be caused by a combination of uptake of complex nutrients and a limited catabolic capacity of the cell, as in the case of lysine, or may originate from a metabolic overflow situation, e.g., in the case of glutamate (18, 19). For lysine, it has been demonstrated that this explanation is in fact true, since absence of the lysine exporter LysE results in growth arrest at elevated cytoplasmic l-lysine concentrations when cells are grown in complex media (2). Amino acid import and export have to be strictly regulated in view of the obvious danger of creating a futile cycle, since the simultaneous presence of energy-dependent uptake and excretion reactions would waste metabolic energy (13). Consequently, it is not surprising that expression of genes encoding amino acid export systems has been shown to be strictly controlled by the cytoplasmic concentration of the respective amino acid (2, 17).

The absence of an appropriate export system for a particular amino acid may cause growth arrest in the presence of nutrient peptides containing this amino acid. Several amino acid export systems from C. glutamicum have been identified by exploiting this observation. Peptide feeding was first introduced for characterizing export of lysine, isoleucine, and threonine (3, 25, 35) and was then successfully used for the identifying exporter proteins for the same three amino acids (17, 32, 34). Here, we have applied an alternative strategy, namely, analysis of gene expression profiles under stress conditions caused by an increased cytoplasmic methionine concentration. One of the genes induced in this stress situation turned out to be that for BrnFE, the major methionine export system of C. glutamicum, which had originally been described as exporter for branched-chain amino acids (32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

The strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Becton-Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) or in minimal medium MM1 (16) at 30°C and 130 rpm. When appropriate, kanamycin (15 or 25 μg ml−1) or chloramphenicol (50 or 100 μg ml−1) was added to the medium.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5αMCR | endA1 supE44 recA1 gyr96 relA1 deoRU169 φ80dlacZΔM15 mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) | 11a |

| C. glutamicum | ||

| ATCC 13032 | Wild type | ATCCb |

| 13032 ΔmetD | Wild type deleted of a 1.8-kb fragment of metD | This work |

| 13032 ΔmetD Δcgl0944 | Wild type deleted of a 1.3-kb fragment of cgl0944 | This work |

| 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE | 13032 ΔmetD deleted of a 1-kb fragment of brnE | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pZ8-1 | Expression vector, ptac, Kmr, ori pUC, ori C. glutamicum | Degussa AG (Halle, Germany) |

| pXMJ19 | Expression vector, ptac, lacIq, Cmr | 14a |

| pK18mobsacB | Integration vector, KmroriVEc oriT sacB | 31 |

| pK18mobsacBΔmetD | pK18mobsacB with a 2-kb fragment carrying the flanking regions of cgl0635 and cgl0636 | This work |

| pK18mobsacBΔCgl0944 | pK18mobsacB with a 2-kb fragment carrying the flanking regions of cgl0944 | This work |

| pK18mobsacBΔbrnE | pK18mobsacB with a 1-kb fragment carrying the flanking regions of brnE | This work |

| pZ8-1brnFE | pZ8-1 carrying the brnFE genes | This work |

| pXMJ19Cgl0944 | pXMJ19 carrying the cgl0944 gene | This work |

Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed in E. coli DH5αMCR from PCR-generated fragments (Master Mix; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) by using C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 DNA as a template. In order to construct pXMJ19Cgl0944, the upstream primer 5′-GCCTGCAGATGACAAATCCCACAGAGG-3′ and the downstream primer 5′-GGAATTCCTATCCGGCGGATACTTC3′ were used. The resulting fragment was PstI and EcoRI digested and cloned into pXMJ19 restricted with the same enzymes. The gene brnFE was amplified by using the upstream primer 5′-GCGCGCGAATTCGTGCAAAAAACGCAAGAGAT-3′ and the downstream primer 5′-CGCGCGGGATCCTTAGAAAAGATTCACCAGTCC-3′. The resulting fragment was EcoRI and BamHI digested and cloned into pZ8-1 restricted with the same enzymes.

Chromosomal deletions were introduced in the C. glutamicum genome according to the protocol described by Schäfer et al. (31), using plasmid pK18mobsacB. All deletions were verified by PCR, and the flanking regions in the genome were sequenced for control (data not shown). For cgl0944 deletion, 1-kb DNA fragments up- and downstream of cgl0944 were amplified via PCR. Primers were designed so that EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites (upstream DNA) or BamHI and PstI restriction sites (downstream DNA) (shown in boldface) were introduced (5′-CGGAATTCCGGCTCTAGCTCCACG-3′, 5′-GCGGATCCGCTTAGAAGAACTACACCG-3′, 5′-GCGGATCCCCACCCAAATAGGCAGG-3′, and 5′-GCCTGCAGGCGGTCTCCGATGACAG-3′). The PCR products were ligated to EcoRI/PstI-restricted pUC19 DNA, leading to plasmid pUC19ΔCgl0944. The generated 2-kb EcoRI/PstI fragment was isolated and ligated to EcoRI/PstI-restricted pK18mobsacB DNA, leading to plasmid pK18mobsacBΔCgl0944, which was applied to generate a chromosomal cgl0944 deletion as described previously (31).

For brnE deletion, two 0.5-kb fragments up- and downstream of brnE were amplified and ligated by crossover PCR (22). The resulting 1-kb fragment was cloned into pK18mobsacB via its attached EcoRI restriction site (restriction site in boldface, overlap underlined: 5′-CTAGGAATTCCTTCCGCCACGTATTCTATG-3′, 5′-CATACTGCGACAACAAGGAG-3′, 5′-CTCCTTGTTGTCGCAGTATGATCCGCATGCCCTCAATTTG-3′, and 5′-CTAGGAATTCTTCACCAACCTGCGCACAAT-3′).

Construction of strains.

C. glutamicum was transformed by electroporation (34), and the presence of replicative plasmids was verified by plasmid reisolation and restriction analysis. The brnE and cgl0944 deletion mutant strains were generated by using pK18mobsacBΔbrnE and pK18mobsacBΔCgl0944, respectively. Clones were selected for kanamycin resistance to establish integration of the plasmid in the chromosome. In a second round of positive selection by using sucrose resistance, clones were selected for deletion of the vector (31). The deletions in the chromosome were verified by PCR analysis.

RNA preparation and hybridization.

Cells cultivated in BHI medium were used to inoculate an overnight culture in 20 ml MM1 medium. The overnight culture was used to inoculate fresh MM1 medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Until the cells reached an OD600 of 5, dipeptides were added and samples were taken at indicated time points.

Total RNA was prepared after disruption of the C. glutamicum cells by glass beads, using the NucleoSpin RNAII kit as recommended by the supplier (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The RNA was blotted onto positively charged nylon membranes (BioBond; Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany), using a Minifold I dot blotter (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Hybridization of digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes was detected with a Fuji luminescent image analyzer LAS1000 (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany), using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin Fab fragments and CSPD as light-emitting substrate as recommended by the supplier (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

For the generation of antisense probes, internal DNA fragments of the corresponding genes were amplified by PCR. The sequence of the T7 promoter (shown in boldface) was added to one of the primers. For cloning of the brnF gene fragment the primer sequences 5′-GCTGCAGGTTTGGGCATG-3′ and 5′-GCGCGCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTGCGAGCAGCAGAGAAG-3′ were used. The hybridization probes were produced by in vitro transcription using T7 polymerase.

Peptide uptake and amino acid export assay.

Cells cultivated in BHI medium were used to inoculate an overnight culture in 20 ml MM1 medium. The overnight culture was washed twice and inoculated into fresh MM1 medium to an OD600 of 2. After preincubation for 45 min at 30°C, the assay of peptide uptake and amino acid excretion was initiated by addition of methionyl-methionine (Met-Met) or of isoleucyl-isoleucine (Ile-Ile) at final concentrations between 1 and 3 mM. Processing of samples for separation of extra- and intracellular fluids was performed by using silicone oil centrifugation with perchloric acid in the bottom layer (28). In the resulting fractions, amino acids were quantified as their o-phthaldialdehyde derivatives via high-pressure liquid chromatography. The intracellular volume used to calculate the internal amino acid concentration was 1.7 μl mg (dry weight)−1 (30).

RESULTS

Methionine excretion in C. glutamicum as a consequence of peptide uptake.

To establish a system in which methionine excretion can be studied experimentally, we optimized the dipeptide feeding strategy. Dipeptides containing the amino acid under study were added to cells, which, after active uptake by peptide transport systems and subsequent hydrolysis by cytoplasmic hydrolases, increases the internal amino acid pool, thus providing an appropriate substrate for amino acid export systems. For a biochemical characterization, this approach is preferable to the use of strains which overproduce amino acids because of deregulated amino acid biosynthesis, since the internal amino acid pool can experimentally be influenced by time, kind, and concentration of the added peptide. Since the specificities of the various peptide uptake systems in C. glutamicum are not known, we tested a number of methionine-containing dipeptides and found that the peptide methionyl-methionine is taken up with reasonably high activity. This peptide was used in most of the following experiments. During optimization of the dipeptide feeding assay, we realized that methionine-containing dipeptides are not only taken up by cells of C. glutamicum but are also hydrolyzed by a peptide hydrolase in the cell wall to a significant extent. As a consequence, in all transport assays perchloric acid was used as stopping agent to immediately quench the hydrolase activity.

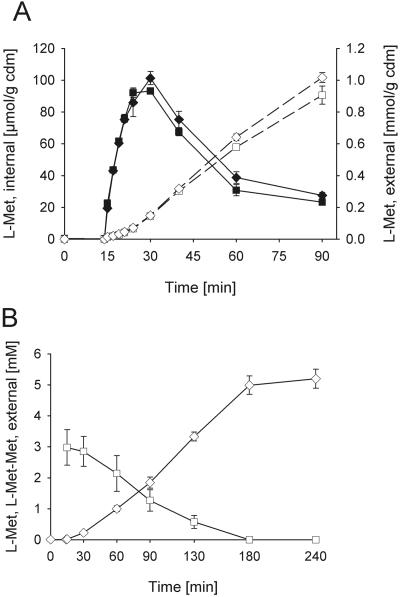

Figure 1 shows the responses of internal and external methionine during methionine production upon addition of Met-Met within the initial time phase (Fig. 1A), as well as the decrease of external dipeptide and the production of external methionine until total consumption of the added peptide (Fig. 1B). Immediately after addition of Met-Met, the internal methionine transiently increased from a low concentration up to values of around 100 μmol/g cell dry mass (CDM) and finally decreased again. The external methionine concentration increased until consumption of the dipeptide. The observed cytoplasmic methionine concentration was below the detection limit before addition of the dipeptide, reached 60 mM at the peak of accumulation, and decreased again to 15 to 20 mM 90 min after the Met-Met addition. These values were calculated on the basis of a cell volume for C. glutamicum of 1.7 μl/mg CDM, as measured in the absence of osmotic stress (30). In the medium, a continuous increase of methionine was observed, arising from both the activity of the excretion system and the external hydrolase. External Met-Met (3 mM) was fully consumed within 3 h (Fig. 1B), and internal dipeptide was not detectable at any time.

FIG. 1.

Methionine excretion in response to addition of 3 mM Met-Met dipeptide. A. Internal (solid symbols) and external (open symbols) methionine was measured in the wild-type strain C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (squares) and C. glutamicum strain ATCC 13032 ΔmetD (diamonds). The dipeptide was added at 14 min after start of the experiment. B. Time courses of decrease of external Met-Met dipeptide (squares) and increase of external methionine (diamonds). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

The fact that the concentration of external methionine at the end of the experiments was in general about 1.8 times the concentration of Met-Met dipeptide added at the beginning indicates a product recovery of around 90%. An example is shown in Fig. 1B, where 5.3 mM methionine is measured externally after consumption of 3 mM added Met-Met dipeptide. Furthermore, from Fig. 1, both dipeptide uptake rates (Fig. 1B) and methionine excretion rates (Fig. 1A and 1B) can be obtained. Not surprisingly, the values coincide with about 15 μmol/(g CDM · min) for methionine excretion (Fig. 1A and 1B) and 8.5 μmol/(g CDM · min) for Met-Met uptake (Fig. 1B) (taking into consideration a cell density of 2.6 g CDM/liter at 90 min), again indicating a recovery of about 90%.

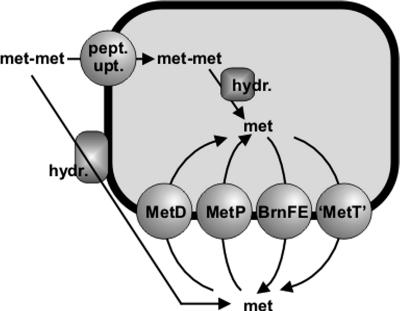

The measured net fluxes of methionine and Met-Met dipeptide shown in Fig. 1 are in principle based on a complex scenario of extracellular, cytoplasmic, and transmembrane metabolic fluxes (Fig. 2). This picture combines peptide uptake (flux a), external peptide hydrolysis (flux b), internal peptide hydrolysis (flux c), intracellular methionine degradation (flux d), methionine export (flux e), and methionine uptake (flux f). Since we were interested in the quantification of transmembrane fluxes related to methionine production in C. glutamicum by using the peptide feeding assay, we adapted the experimental setup appropriately and measured some of the reactions separately in order to be able to finally dissect the true rate of methionine uptake from all other possible interfering rates.

FIG. 2.

Schematic drawing of metabolic and transmembrane methionine fluxes considered in the text. External methionyl-methionine dipeptide is taken up by peptide uptake systems. Internal methionine results from hydrolysis of methionine-containing peptides in the cytoplasm and from methionine uptake via the two uptake systems (MetD and MetP). External methionine results from hydrolysis of methionine-containing peptides by a membrane-bound peptide hydrolase activity and from methionine excretion by the two methionine export systems (BrnFE and “MetT”).

The observation of a methionine recovery of around 90% (see above) indicates that cytoplasmic methionine degradation, i.e., flux d, does not significantly contribute to the overall flux estimation. We furthermore completely abolished the possibly interfering reuptake of methionine into the cell. The kinetic analysis of methionine uptake in C. glutamicum revealed, as in E. coli (15), the presence of at least two different uptake systems, one with high affinity (0.5 μM) and one with medium affinity (15 μM) (results not shown). A detailed characterization of methionine uptake systems in C. glutamicum will be described elsewhere. The high-affinity system was found to be encoded by an operon similar to that for MetD of E. coli, an ABC-type transporter (11, 23). Deletion of any single gene of this gene cluster led to abolishment of high-affinity methionine uptake in C. glutamicum (results not shown). The medium-affinity transport system was found to be a secondary carrier encoded by a so-far-unknown gene. We analyzed the substrate specificity of this uptake system and found that methionine uptake could be efficiently inhibited by addition of excess cysteine, valine, leucine, or isoleucine. The simultaneous presence of 30 μM leucine or, alternatively, 100 μM cysteine blocked uptake of 20 μM methionine to more than 95% (results not shown). Consequently, most of the following experiments designed to analyze methionine efflux in C. glutamicum were carried out with a strain in which the MetD system was inactive due to the deletion of the ATP binding protein and the permease subunits, and the secondary system was completely inhibited by addition of 4 mM cysteine and 10 mM leucine where indicated. Under these conditions, no uptake of labeled methionine can be measured. For comparison, in Fig. 1A, the basic peptide feeding experiment is shown either with the wild type without or strain 13032 ΔmetD with added cysteine and leucine.

The increase of internal methionine followed by a decrease to a low internal methionine concentration comparable to that observed under conditions where reuptake of methionine is blocked argues for a significant contribution of methionine excretion to the increase of external methionine. A proof for this interpretation was provided by the following experiments, including deletion and overexpression of the corresponding export system (see below). Furthermore, the lack of detectable internal dipeptide in these experiments strongly argues for the fact that internal hydrolysis is not rate limiting; at least it must be significantly faster than Met-Met uptake. Consequently, flux c is not rate limiting and thus is not relevant for interpreting the time course of the increase of external methionine.

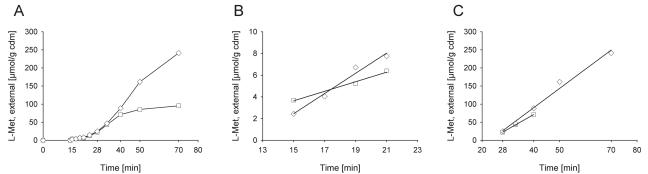

The observed decrease of external Met-Met peptide is the sum of uptake (flux a) and external hydrolysis (flux b), or, vice versa, the increase of external methionine is the sum of methionine excretion (flux e) and external hydrolysis (flux b). For an estimation of the external hydrolase activity, we took advantage of the observation that hydrolysis starts immediately after addition of the dipeptide, whereas the start of methionine excretion is strongly delayed in a strain in which the main export system has been deleted (see below). We thus analyzed external methionine in strain 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE within the first 20 min after dipeptide addition and found biphasic kinetics of methionine accumulation (Fig. 3). In this analysis, the initial phase is related to the activity of the external hydrolase, whereas the second phase includes both hydrolysis and activity of the excretion system BrnFE. Based on the data in Fig. 3, hydrolysis of Met-Met dipeptide in the first 5 min occurred at rates of 0.45 and 0.93 μmol/g CDM · min in the presence of 1 and 3 mM peptide, respectively. In this time range, the internal methionine concentration was below 20 mM and thus far below the value where high activity of the second excretion system was observed (around 70 mM [see below]). In relation to the values of 4.1 and 5.3 μmol/g CDM · min, which were measured after onset of methionine excretion, the hydrolase activity amounts to 12 and 21% of the excretion activity at 1 and 3 mM of peptide added, respectively. Consequently, around 80 to 90% of the rate of increase of external methionine measured under the conditions described in Fig. 1 is related to the activity of methionine efflux.

FIG. 3.

Resolution of time dependence of methionine excretion in strain 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE in response to addition of 1 mM (squares) and 3 mM (diamonds) methionyl-methionine. Dipeptide was added 14 min after the start of the experiment; only the external methionine concentration is shown. A, full time course; B, increase of external methionine immediately after addition of dipeptide; C, increase 10 to 50 min after addition of dipeptide. The straight lines connecting the data points in panels B and C were derived by linear regression and were used for calculating the respective rates of methionine export mentioned in the text. The experiment was performed in the presence of 10 mM leucine and 4 mM cysteine to inhibit methionine uptake.

BrnFE is a methionine export system.

As an approach to identify possible methionine export systems, we applied a DNA microarray assay using a methionine-overproducing strain of C. glutamicum (8). In this strain, the genes coding for transcription factors of methionine biosynthesis (mcbR and hcbR, an gene located adjacent to the methionine biosynthesis genes) (27, 29) were deleted, genes encoding enzymes of methionine biosynthesis (metXEY) were overexpressed, and the S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (metK) was decreased by point mutation of its gene to 65% of its original activity (8). This strain produced small amounts of methionine in later states of fermentation. We compared mRNAs from this strain before and during the methionine production phase by the use of microarrays and found that the genes of two membrane proteins were significantly overexpressed, namely, genes cgl0944 and brnF. The gene cgl0944 is annotated as a multidrug resistance transporter, and brnF encodes the larger subunit of the isoleucine export system BrnFE (17).

We first studied the membrane protein Cgl0944. The gene was deleted in frame in the parental strain 13032 ΔmetD lacking the MetD methionine uptake system. The resulting strain, 13032 ΔmetD Δcgl0944, was tested with respect to its ability to excrete methionine. However, no significant difference was found in the time courses of both internal and external methionine concentrations (results not shown). In order to confirm that Cgl0944 is not involved in methionine excretion, we overexpressed the corresponding gene in the same parental strain, which again did not lead to a significant change in methionine efflux (results not shown).

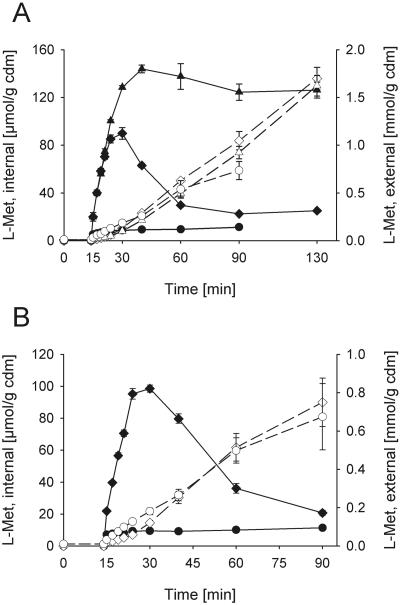

We analyzed the significance of BrnFE, the isoleucine export system of C. glutamicum, for methionine excretion. Deletion of brnE dramatically changed the time course of internal methionine concentration in response to Met-Met addition (Fig. 4A). The initial increase of the cytoplasmic methionine pool was identical to that observed in strain 13032 ΔmetD. After a few minutes, however, the internal methionine level reached much higher values, and a steady-state concentration of around 130 μmol/g CDM, corresponding to 75 mM methionine, was observed. Surprisingly, the change in internal methionine concentration was not reflected in the time course of accumulation of external methionine, which reached a value of about 10 μmol/g CDM · min, closely similar to the rate reported in Fig. 1. As a matter of fact, we never observed rates of external methionine accumulation higher than those reported in Fig. 1 and 4, independent of the state of activity of BrnFE. This observation is due to the fact that the rate of methionine efflux corresponds to the maximum rate of peptide uptake (Fig. 1B), which can of course not be exceeded by methionine excretion in a steady-state situation of uptake and excretion.

FIG. 4.

Dependence of methionine excretion on the presence of the brnE gene. Internal (solid symbols) and external (open symbols) methionine concentrations are shown. A. Deletion of and complementation by gene brnE. The strains 13032 ΔmetD (diamonds), 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE (triangles), and 13032 Δmet ΔbrnE(pZ8-1brnFE) (circles) were compared. B. Overexpression of brnFE. The strains 13032 ΔmetD(pZ8-1) (diamonds) and 13032 ΔmetD(pZ8-1brnFE) (circles) were compared. The experiment was performed in the presence of 10 mM leucine and 4 mM cysteine to inhibit methionine uptake. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

As a control, we also constructed a cgl0944 brnE double-deletion mutant. This strain showed levels of internal methionine closely similar to those of the strain carrying the brnFE deletion only, thus confirming that cgl0944 is not related to methionine excretion (results not shown).

To achieve stable overexpression of brnFE independent of its native regulation, brnFE was cloned without its original promoter in plasmid pZ8-1 (pZ8-1brnFE). Strain 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE could be complemented by transformation with this plasmid. Complementation led to a significant decrease in internal methionine accumulation in response to Met-Met addition (Fig. 4A), indicating a strongly increased activity of BrnFE (Fig. 4B). In this strain, cytoplasmic methionine never exceeded a low internal steady-state concentration of 22 μmol/g CDM, corresponding to about 13 mM.

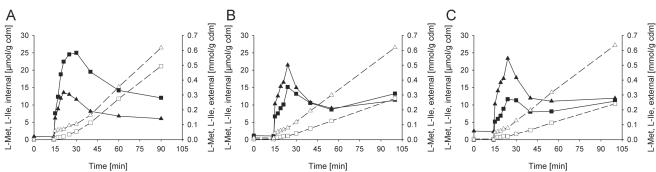

Taken together, these results demonstrate that BrnFE, besides being responsible for export of isoleucine, leucine, and valine, also efficiently catalyzes excretion of methionine. It was now interesting to know which amino acid is preferred by BrnFE as a transport substrate. In order to answer this question, we added various mixtures of Met-Met and Ile-Ile dipeptides and measured the internal concentrations of the two amino acids as well as rates of increase of external amino acids. The use of dipeptides containing both Ile and Met was not successful because of low uptake rates for these peptides (results not shown). By the peptide feeding approach we were able to achieve different concentration ratios of cytoplasmic methionine and isoleucine. In Fig. 5, the results of three different experiments in which 1 mM external Met-Met was added together with increasing concentrations of Ile-Ile between 1 and 1.7 mM are shown. The external presence of Ile-Ile in addition to Met-Met reduced the amount of transient internal methionine accumulation due to competition of the two dipeptides at the level of the corresponding uptake system. Addition of Ile-Ile also reduced the rate of methionine export because of competition of isoleucine and methionine as substrates for BrnFE-mediated transport.

FIG. 5.

Competition for excretion via BrnFE by cytoplasmic isoleucine and methionine. At 14 min after the start of the experiment, the dipeptides isoleucyl-isoleucine and methionyl-methionine were added in different concentrations. The internal (solid symbols) and external (open symbols) concentrations of methionine (squares) and isoleucine (triangles) are shown. The concentration ratios applied were (in mM methioninyl-methionine/mM isoleucinyl-isoleucine) 1:1 (A), 1:1.3 (B), and 1:1.7 (C). The experiment was performed in the presence of 10 mM leucine and 4 mM cysteine to inhibit methionine uptake.

To obtain true values for the internal substrate specificity of BrnFE, or, in other words, for the different excretion rates of methionine and isoleucine, the rates of external dipeptide hydrolysis have to be subtracted. They were determined for the Ile-Ile dipeptide exactly as described for the Met-Met dipeptide and were subtracted from the rate of increase of external amino acids (Fig. 3 and results not shown). For the experiments described in Fig. 5, the shares of external hydrolysis were determined to be 12% and 42% of the total increase in external amino acid for methionine and isoleucine, respectively. Taking these numbers in account, an evaluation of internal competition between methionine and isoleucine is possible. In the experiment using 1 mM of each dipeptide, the internal concentration ratio was determined to about 2 (Met/Ile), and the ratio of true efflux rates after subtraction of external hydrolysis was 1.1 (Met/Ile) (Fig. 5A). The corresponding numbers for the experiment using 1 mM Met-Met together with 1.3 and 1.7 mM Ile-Ile dipeptide are 0.9 and 0.6 for the internal concentration ratio (Met/Ile) and 0.6 and 0.45 for the true rates of efflux (Met/Ile), respectively (Fig. 5B and 5C). Consequently, a slight preference of BrnFE for the substrate isoleucine was revealed by these experiments.

Expression regulation of transport systems involved in methionine efflux.

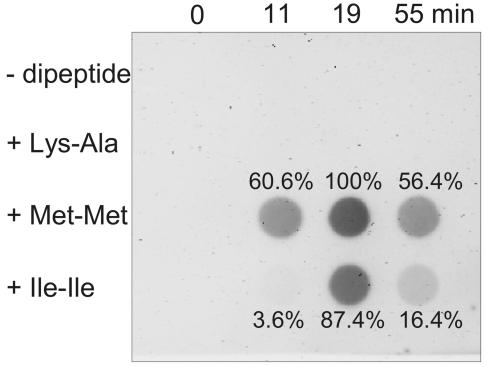

A gene encoding an Lrp-type transcription factor located adjacent to the brnFE operon was identified as being responsible for regulation of brnFE (17). Since we found that methionine, in addition to the previously described branched-chain amino acids, is also a substrate for BrnFE, we studied the regulation of brnFE expression in response to elevated amounts of different amino acids in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6). For this purpose, we again applied the peptide feeding assay with addition of various dipeptides and analyzed RNA synthesis by a dot blot assay using brnF as a probe. Addition of 3 mM of the dipeptides Lys-Ala, Met-Met, and Ile-Ile led to peak internal amino acid concentrations after 2 min of around 40 mM. Whereas no induction was observed in the presence of Lys-Ala dipeptide, both Met-Met and Ile-Ile efficiently induced brnFE. Expression caused by increased internal methionine was stronger and, in particular, faster than that caused by elevated isoleucine concentrations.

FIG. 6.

Dot blots of brnF expression in response to addition of dipeptides. At 9 min after the start of the experiment, the three different dipeptides lysyl-alanine, methionyl-methionine, and isoleucyl-isoleucine were added to a suspension of C. glutamicum cells. RNA was isolated at the times indicated at the top of the blot and assayed with a brnF probe. The values adjacent to the dot blot signals are the results of the spot quantification (see Materials and Methods).

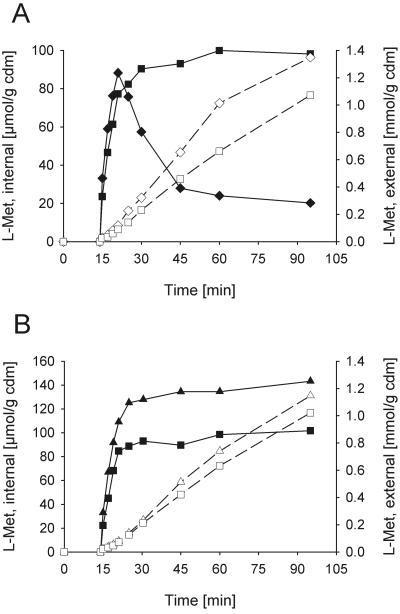

The fact that the brnFE operon is effectively regulated at the level of expression was used to analyze the response of the observed total activity of methionine excretion in dependence of the internal amino acid pool. For this purpose, we added 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol together with the Met-Met dipeptide at the same time (Fig. 7A). The presence of the inhibitor fundamentally changed the time course of internal methionine accumulation; however, the rate of amino acid excretion was not much different from that observed for the untreated strain. The reason for this observation, as explained above, is most probably the limitation by the capacity of peptide uptake. It is important to note that the time course of the cytoplasmic methionine concentration in the chloramphenicol-treated strain (Fig. 7A) was very similar to that of the strain in which brnFE was deleted (Fig. 4A and 7B). This indicates that the share of methionine export activity which is subject to expression regulation is identical to the share catalyzed by BrnFE. Moreover, since we observe similar rates of methionine excretion in the absence and in the presence of chloramphenicol as well as in the brnFE deletion strain, an additional methionine exports system(s) besides BrnFE must be present in C. glutamicum. The small decrease of methionine export observed upon addition of chloramphenicol (Fig. 7B) can most probably be explained by negative effects of the inhibitor on the expression of the dipeptide uptake system(s), which is thought to be the rate-limiting step.

FIG. 7.

Influence of chloramphenicol addition on methionine efflux. Internal (solid symbols) and external (open symbols) methionine concentrations are shown. A. Strain 13032 ΔmetD was used in the absence (diamonds) and presence (squares) of 100 μg/ml of chloramphenicol. B. Same as in A, except strain 13032 ΔmetD ΔbrnE was used. The experiment was performed in the presence of 10 mM leucine and 4 mM cysteine to inhibit methionine uptake.

The results further indicate that this so-far-unidentified methionine excretion system seems to be constitutively expressed. In view of the relatively high internal concentration of methionine at which the activity of this system was observed in the brnFE deletion strain, it may be speculated that methionine efflux under these conditions is mediated by mechanosensitive efflux channels. The presence of at least two types of these channels has been proven for C. glutamicum (24, 30). Upon application of hypo-osmotic conditions, relatively selective efflux of betaine, proline, and ectoine was observed in C. glutamicum (30). Consequently, we tested, under conditions of methionine efflux in the brnFE deletion strain mediated by the putative second methionine export system, whether proline also is released in combination with methionine. Since this was not the case (results not shown), involvement of mechanosensitive efflux channels in methionine export seems unlikely.

DISCUSSION

Methionine efflux in bacterial cells has not been described or analyzed so far. Since efficient methionine efflux from C. glutamicum would be an essential prerequisite for a fermentative process for methionine production using this organism, we were interested in this excretion process. For its characterization, we used a peptide feeding approach, which was first introduced for the analysis of lysine and isoleucine export in C. glutamicum (3, 4, 13, 35) and was also used for the identification of the threonine exporter ThrE (32), as well as for BrnFE, an exporter for branched-chain amino acids (17). Using this approach, we provide experimental evidence for the presence of at least two export systems for methionine in C. glutamicum. For a correct quantification in the peptide feeding assay of the observed methionine fluxes mediated by the various transport systems involved, it was necessary to determine also the rate of peptide hydrolysis due to the presence of external, membrane-bound hydrolases. It should be pointed out that this fact had been not taken into consideration by earlier investigations using the method of peptide feeding for inducing and testing amino acid efflux systems.

In order to identify the transport system(s) responsible for methionine export in C. glutamicum, we analyzed gene expression by application of DNA microarrays under stress conditions caused by elevated cytoplasmic methionine concentrations. Two transport systems responded to this particular situation with increased expression. One of them was BrnFE, which has previously been characterized as an export system for branched-chain amino acids. By using the peptide feeding assay, BrnFE was shown to be able to catalyze efficient export of methionine, provided that the internal concentration of this amino acid reaches significant levels. As expected, BrnFE turned out to be efficiently regulated on the level of expression. The brnFE mRNA content responded to an internal increase in methionine starting from very low levels. In agreement with this observation, a steep increase in cytoplasmic methionine concentration was found to precede the excretion phase, indicating a low level of methionine excretion capacity, i.e., a low level of brnFE expression, at the beginning of the peptide feeding experiment. During active excretion, the internal methionine concentration returned to low levels due to the function of the strongly induced export system BrnFE, and this could be prevented upon inhibiting translation by chloramphenicol. Induction of brnFE was more efficient in response to an elevated level of methionine compared to isoleucine, another substrate of BrnFE.

The preference for methionine as an inducer does not fully coincide with the export carrier's substrate specificity, since isoleucine turned out to be slightly preferred as a transport substrate. A difference between inducing capacity and transport affinity has also been observed in the case of LysE, the lysine export carrier of C. glutamicum, where lysine and arginine, but not histidine, were identified as substrates, whereas all three were found to be able to induce expression of lysE (2). It is difficult to directly determine the transport affinity of an export carrier, since internal amino acid concentrations are not freely accessible to experimental variation. The observation of a steady-state internal methionine concentration of around 10 mM at a constant influx into (peptide uptake and internal hydrolysis) and efflux out of (excretion) the cytoplasmic methionine pool suggests a transport Km not far from this steady-state value of around 10 mM. In spite of high specificity, low internal affinity has also been observed for other excretion carriers (4, 5, 17, 33). In terms of physiology, this observation makes sense in view of the fact that export is thought to occur only under conditions of elevated internal amino acid concentrations. This fact is furthermore relevant for avoidance of futile cycling of methionine by both energy-dependent uptake and efflux. The isoleucine export system BrnFE has previously been shown to be coupled to the electrochemical proton potential (13, 17) and thus uses metabolic energy for active extrusion of its substrate, as it is the case for both methionine uptake systems. The main strategy to avoid futile cycling in the absence of a situation of metabolic imbalance, however, was shown to be provided by the tight regulation of brnFE expression.

The Vmax value of BrnFE for methionine export could not be estimated under the conditions of the peptide feeding assay since the rate of methionine export turned out to be limited by the capacity of the peptide uptake system. The observed export rate of about 10 μmol/(g CDM · min) thus represents the lower limit for this value. This interpretation was corroborated by several observations. First, we directly measured uptake of Met-Met dipeptide, which in fact turned out to be half of the value observed for maximum methionine efflux (Fig. 1). It was not possible to directly reduce the rate of Met-Met uptake by using limiting amounts of peptide because of the high affinity of the peptide uptake system. Second, the experiments involving internal competition of methionine efflux by isoleucine argue for the efflux system working under nonsaturating conditions, since the presence of cytoplasmic isoleucine concentrations below those of methionine led directly to a decrease of methionine export.

We also provide evidence for at least one further methionine excretion system in C. glutamicum besides BrnFE. This export system seems to be constitutively expressed and seems to have a very low affinity for methionine but a high transport capacity. Significant methionine export via this excretion system was observed only at internal methionine concentrations of higher than 50 mM; consequently, the apparent affinity of the export system should be in this range. For the same reasons as discussed for the case of BrnFE, namely, the limited capacity of the peptide uptake system, only a lower limit for Vmax could be measured. The low substrate affinity suggests either that this system may be an unspecific emergency system for amino acid export in general or that methionine export observed at high cytoplasmic concentrations is due to the side activity of an excretion system specific for another substrate.

Not surprisingly, the methionine export rate measured under these conditions was very similar to that measured previously for isoleucine excretion, since export of this amino acid is also mediated by BrnFE (17) and a similar peptide feeding assay was used in this work, most probably leading to the same limitation. Moreover, export of methionine is in the same range as measured for lysine in C. glutamicum and threonine in E. coli (2, 3, 4, 5, 33). It is certainly higher than the value observed for threonine in C. glutamicum (25, 32) and far lower than the highly effective glutamate excretion by this organism (12, 14). Our results furthermore indicate that in the presence of reasonably high internal methionine concentrations, not exceeding a value of around 30 mM, BrnFE and not the additional system which operates only at highly elevated internal methionine concentrations will be nearly exclusively responsible for methionine excretion. An overview of the transmembrane and metabolic fluxes which have been considered in this work is given in Fig. 2.

C. glutamicum is in general thought not to be equipped with regulation networks as sophisticated as found in many other bacteria, e.g., E. coli or Bacillus subtilis. This has often been used as an argument for explaining the extraordinary capacity of this organism to excrete amino acids because of an increased possibility of encountering situations of metabolic imbalance (6, 18, 19, 20). In a number of cases, however, which have been studied in detail, this does not seem to be true, e.g., for nitrogen control (7) and also for biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids (27, 29). In this work, C. glutamicum was shown to harbor at least two different excretion systems which are able to catalyze active efflux of methionine. Consequently, the function of excretion carriers as metabolic relief valves designed for cases of metabolic imbalance (6, 18, 19, 20) seems to be of high physiological significance, even in the case of tightly regulated anabolic pathways. The metabolic conditions, i.e., peptide feeding, used here as a test system for the functional characterization of amino acid export at the same time also seem to be the most likely explanation for the physiological significance of active methionine export. In the presence of a low capacity for methionine degradation, active uptake of methionine-containing peptides may result in an increase of internal methionine and consequently in an imbalanced situation of cell metabolism, which may be relieved by the action of BrnFE.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Kalinowski and D. Rey, University of Bielefeld, for communication of information concerning regulation of methionine biosynthesis in C. glutamicum prior to publication as well as for several constructs which were helpful in the investigations on methionine uptake. We are furthermore grateful to L. Eggeling and N. Kennerknecht, Research Center Jülich, for the pJC1brnFE plasmid.

We are grateful to DEGUSSA AG for generous financial support of this project. This work was partially funded by a Hermann-Schlosser fellowship from DEGUSSA AG to C.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banik, A. K., and S. K. Majumdar. 1974. Studies on methionine fermentation. I. Selection of Micrococcus glutamicus and optimum conditions for methionine production. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 12:363-365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellmann, A., M. Vrljic, M. Patek, H. Sahm, R. Krämer, and L. Eggeling. 2001. Expression control and specificity of the basic amino acid exporter LysE of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology 147:1765-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bröer, S., and R. Krämer. 1991. Lysine secretion by Corynebacterium glutamicum. 1. Identification of a specific secretion carrier system. Eur. J. Biochem. 202:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bröer, S., and R. Krämer. 1991. Lysine secretion by Corynebacterium glutamicum. 2. Energetics and mechanism of the transport system. Eur. J. Biochem. 202:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bröer, S., L. Eggeling, and R. Krämer. 1993. Strains of Corynebacterium glutamicum with different lysine productivities may have different lysine excretion systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:316-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkovski, A., and R. Krämer. 2002. Bacterial amino acid transport proteins: occurence, functions, and significance for biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkovski, A. 2003. Ammonium assimilation and nitrogen control in Corynebacterium glutamicum and its relatives: a new type of regulation in actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:617-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deutenberg, D. 2003. Diploma thesis, University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany.

- 9.Eggeling, L., and H. Sahm. 1999. l-Glutamate and l-lysine: traditional products with impetuous developments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:146-153. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggeling, L., and H. Sahm. 2003. New ubiquitous translocators: amino acid export by Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 180:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gál, J., A. Szvetnik, R. Schnell, and M. Kálmán. 2002. The metD d-methionine transporter locus of Escherichia coli is an ABC transporter gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 184:4930-4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Grant, S. G. N., J. Jessee, F. R. Bloom, and D. Hanahan. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. USA 87:4645-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutmann, M., C. Hoischen, and R. Krämer. 1992. Carrier mediated glutamate secretion by Corynebacterium glutamicum under biotin limitation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1112:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann, T., and R. Krämer. 1996. Mechanism and regulation of isoleucine excretion in Corynebacterium glutamicum, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3238-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoischen, C., and R. Krämer. 1989. Evidence for an efflux carrier system involved in the secretion of glutamate by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch. Microbiol. 151:342-347. [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Jakoby, M., C. E. Ngoutou-Nkili, and A. Burkovski. 1999. Construction and application of new Corynebacterium glutamicum vectors. Biotechnol. Tech. 13:437-441. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadner, R. J., and W. J. Watson. 1974. Methionine transport in Escherichia coli: physiological and genetic evidence for two uptake systems. J. Bacteriol. 119:401-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kase, H., and K. Nakayama. 1975. l-Methionine production by methionine analog-resistant mutants of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Agric. Biol. Chem. 39:153-160. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennerknecht, N., H. Sahm, M. R. Yen, M. Patek, M. H. Saier, Jr., and L. Eggeling. 2002. Export of l-isoleucine from Corynebacterium glutamicum: a two-gene-encoded member of a new translocator family. J. Bacteriol. 184:3947-3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krämer, R. 1994. Secretion of amino acids by bacteria—physiology and mechanism. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 13:75-93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krämer, R. 1996. Genetic and physiological approaches for the production of amino acids. J. Biotechnol. 45:1-21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krämer, R. 2004. Production of amino acids: physiological and genetic approaches. Food Biotechnol. 18:171-216. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leuchtenberger, W. 1996. Amino acids—technical production and use, p. 455-502. In H. J. Rehm and G. Reeds (ed.), Products of primary metabolism. Biotechnology, vol. 6. VHC, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link, A. J., D. Phillips, and G. M. Church. 1997. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol. 179:6228-6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merlin, C., G. Gardiner, S. Durand, and M. Masters. 2002. The Escherichia coli metD locus encodes an ABC transporter which includes Abc (MetN), YaeE (MetI), and YaeC (MetQ). J. Bacteriol. 184:5513-5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nottebrock, D., U. Meyer, R. Krämer, and S. Morbach. 2003. Molecular and biochemical characterization of mechanosensitive channels in Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmieri, L., D. Berns, R. Krämer, and M. Eikmanns. 1996. Threonine diffusion and threonine transport in Corynebacterium glutamicum and their role in threonine production. Arch. Microbiol. 165:48-54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham, C. B., F. C. F. Galves, and W. G. Padolina. 1992. Methionine production by batch fermentation from various carbohydrates. ASEAN Food J. 7:34-37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rey, A. D., A. Pühler, and J. Kalinowski. 2003. The putative transcriptional repressor McbR, member of the TetR-family, is involved in the regulation of the metabolic network directing the synthesis of sulphur containing amino acids in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 103:51-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rottenberg, H. 1979. The measurement of membrane potential and delta pH in cells, organelles and vesicles. Methods Enzymol. 55:547-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rückert, C., A. Pühler, and J. Kalinowski. 2003. Genome-wide analysis of the l-methionine pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum by targeted gene deletion and homologous complementation. J. Biotechnol. 104:213-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruffert, S., C. Lambert, H. Peter, V. F. Wendisch, and R. Krämer. 1997. Efflux of compatible solutes in Corynebacterium glutamicum mediated by osmoregulated channel activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:572-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simic, P., H. Sahm, and L. Eggeling. 2001. l-Threonine export: use of peptides to identify a new translocator from Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:5317-5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Rest, M. E., C. Lange, and D. Molenaar. 1999. A heat shock following electroporation induces highly efficient transformation of Corynebacterium glutamicum with xenogenic plasmid DNA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:541-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vrljic, M., H. Sahm, and L. Eggeling. 1996. A new type of transporter with a new type of cellular function: l-lysine export from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol. Microbiol. 22:815-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zittrich, S., and R. Krämer. 1994. Quantitative discrimination of carrier-mediated excretion of isoleucine from uptake and diffusion in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 176:6892-6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]