Abstract

Internalization of culturally dominant masculine gender role norms can have harmful impacts on the physical and emotional health of men and boys. Although parents play an important role in influencing gender-related beliefs in their children, limited research has examined how contemporary parents conceptualize masculinity and their role in gender socialization. The current study conducted 13 focus groups with Black, Latino, and White parents (N = 83) of school-age boys from rural and urban areas in a large southeastern state in the US. Parent beliefs about masculinity existed across a spectrum from “rigid” (representing narrow, culturally dominant masculine norms) to “flexible” (defining a broader set of behaviors and attitudes as masculine). In general, more flexible beliefs were expressed by mothers than fathers, and by White than Black and Latino parents. Most parents reacted positively to messages about potential harms associated with restrictive masculinity norms; however, many saw these issues primarily as parenting challenges (e.g., teaching boys to resist negative peer influences) rather than related to gender socialization. Some unique themes also emerged within racial/ethnic groups, with Black parents noting the impact of racial discrimination on societal expectations for Black men and fathers, and Latino parents describing generational shifts towards more equitable gender role attitudes and parenting practices. These findings highlight the need for more complex and nuanced messages about masculinity norms and their relationship to health and well-being and can help inform the development of interventions to promote healthy masculine gender socialization, increase health equity, and prevent injury and violence.

Keywords: Masculinity norms, parenting, masculine gender role socialization, race/ethnicity, violence, injury prevention

Men and boys face social expectations–or, masculine gender role norms– prescribing a set of traits and behaviors that serve to define, and enforce, the “masculine ideal” (Leaper & Friedman, 2007). Males are expected to be tough, stoic, self-sufficient, ready to fight, risk-takers, demonstrably heterosexual, socially and physically dominant, and in pursuit of status and power (Heilman, Barker, & Harrison, 2017; Leone & Parrott, 2018; Mahalik, Talmadge, Locke, & Scott, 2005). Although gender role attitudes are evolving in American culture (Donnelly et al., 2016; Scarborough et al., 2019), many boys and men still feel pressure to adhere to these culturally dominant masculine norms. For example, 59% of US men in a recent survey said they were taught by their parents to act strong even if they felt nervous or scared, and 52% felt society taught them it was not good for a boy to learn how to cook, sew, clean, or care for children (Heilman et al., 2017). Another study found that one in three US boys (ages 10–17) believe that society most values strength and toughness in boys (35%), expects them to hide or suppress their feelings (33%), and expects them to be tough, strong, and “suck it up” when they feel sad or scared (34%) (Plan International, 2018). These norms are taught and reinforced for boys, both implicitly and explicitly, in early childhood and adolescence and, once formed, remain relatively stable across time (Mahalik et al., 2005).

Many aspects of masculine identity encourage positive behavioral norms in men and boys— such as courage and heroism, a duty to protect and care for others, and the role of worker-provider—that serve critical roles in the structure of society (e.g., Kiselica, Benton-Wright, & Englar-Carlson, 2016). However, substantial evidence suggests that exposure and adherence to other culturally dominant conceptions of masculinity—such as those emphasizing the importance of stoicism, dominance, physical and psychological strength, aggression, and power— can have a detrimental effect on the physical and emotional health of men and boys (Courtenay, 2003, 2011; Mahalik et al., 2007; Ragonese et al., 2019; Wong, Ho, Wang, & Miller, 2017). Males are substantially more likely than females to die by homicide, suicide, and unintentional injury (Heron, 2021). Further, males experience higher rates of chronic disease and death at all ages and for nearly all leading causes of death compared to females, despite the greater social and economic power afforded to men by historically patriarchal and gender-inequitable social structures (Courtenay, 2003; Heron, 2021).

Acceptance of masculine gender norms—which tend to encourage emotional suppression and discourage help-seeking—can also impact men’s mental health, manifesting in a greater risk for depression, maladaptive coping styles, relationship problems, and suicide (Blazina & Watkins, 2000; Cleary, 2012; Reidy, Smith-Darden, Cortina, Kernsmith, & Kernsmith, 2018; Seidler, Dawes, Rice, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2016). A recent study estimated that harmful masculine norms cost the US economy at least $15.7 billion per year—including economic and public health costs (e.g., property damage, lost productivity/quality of life) of traffic accidents, suicide, depression, sexual violence, bullying, physical violence, and binge drinking (Heilman, Guerroro-Lopez, Rogonese, Kelberg, & Barker, 2019).

Recent strategies developed to address these norms and mitigate their harm have often focused on adolescents and young adults and other mechanisms of socialization such as peer norms and media messages (Amin, Kagesten, Adebayo, & Chandra-Mouli, 2018; Graham et al., 2021; Levy et al., 2020; Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, & Lippman, 2013). However, the process of gender socialization begins much earlier in childhood with parents as a primary socializing influence (Leaper & Friedman, 2007; UNICEF, 2022). Indeed, parents play a significant role in shaping gender expectations in their children, both directly and indirectly (Berke et al., 2018; Leaper & Friedman, 2007). Beliefs may be conveyed, for example, through behavior modeling (e.g., engaging in stereotypical behaviors), implied expectations (e.g., supplying gender-typed toys), or reinforcing stereotypes (e.g., “boys don’t cry”; Berke et al., 2018; Leaper & Friedman, 2007). Research on emotional expression has found that mothers talk more to girls than boys about sadness and fear (Fivush, Brotman, Buckner, & Goodman, 2000), that fathers tend to disregard or discourage displays of sadness by children while mothers encourage it (Cassano, Perry-Parrish, & Zeman, 2007), and that fathers attend more to expressions of sadness, anxiety, and submission in girls, and to anger and “disharmonious” emotions in boys (Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005). Some evidence suggests that differences in parental attention to emotional expression by gender predicts the type and level of emotions later expressed by the child, and their mental and behavioral health outcomes (e.g., Chaplin et al., 2005). Further, mothers and fathers who adhere to culturally dominant masculine role norms may be less likely to seek mental health services for their children when needed (Triemstra, Nice, Peer, & Christian-Brandt, 2017). Together, these finding suggest a need for prevention strategies that shape healthy constructions of masculinity in younger children and protect them from negative outcomes across the lifespan, with parents and caregivers as a critical target for intervention.

Despite substantial evidence that parental gender-related beliefs play a role in health outcomes for boys, there is little empirical evidence about the ways in which contemporary parents conceptualize masculinity and their role in socializing gender in their sons. Societal-level attitudes in the US are shifting towards more egalitarian gender roles (Donnelly et al., 2016; Scarborough, Sin, & Risman, 2019); yet research suggests those attitudes may become more traditional during the transition to parenthood, especially among men and parents of daughters (Perales, Jarallah, & Baxter, 2018). In addition, parents’ gender role norms and expectations are likely influenced in unique ways by socio-demographic factors, given evidence of attitudinal differences by race, gender, and region among adults (Carter, Carter, & Corra, 2016; Powers et al., 2003; Silva, 2022). For example, one U.S. based study found both gender and race differences in masculine ideology, with women holding less traditional views than men and White Americans holding less traditional views than Black Americans (Levant, Majors, & Kelley, 1998). Men in rural areas also tend to endorse more traditional attitudes than those living in urban areas; however, these differences are stronger for White men than Black or Latino men, suggesting the importance of other cultural variations in beliefs regarding masculinity (Silva, 2022). Less research has been conducted specifically among parents. One study on young expectant fathers indicated that Black men endorsed more traditional masculine norms than Latino or White men (Gordon, Nichter, Henriksen Jr., 2013). Similarly, other research has found that Black fathers tended to endorse a combination of more and less traditional masculine ideologies including emotional restriction, self-reliance, toughness, as well as family and community connectedness (Doyle et al., 2015). Collectively, these findings suggest the importance of considering how a person’s gender, race, place of residence, and other factors influence their beliefs around masculinity and related parenting practices.

The Current Study

Understanding how contemporary parents conceptualize and socialize masculine gender role norms can help inform interventions to support parents in recognizing potential harms of some norms, like emotional restriction, and change their parenting practices to support the development of positive masculine identities and norms (e.g., role flexibility, emotional and physical health, connectedness, non-violence). More work is needed to address the important role of parents and caregivers in the development of a child’s gender self-concept. To inform the development of effective interventions aimed at changing social norms and parenting practices related to masculinity, the current study conducted focus groups with a diverse set of US mothers and fathers of school-age boys to explore three primary research questions:

How do contemporary parents view masculinity norms and their role in parenting boys?

How do parents react to norms-challenging messages regarding masculine socialization?

Are unique beliefs and reactions expressed by gender, among racial and ethnicity minority groups, and by parents from rural versus urban communities?

This knowledge can help prevention developers understand the information, messages, and skills that will best engage, motivate, and prepare parents and caregivers to communicate and support healthy gender-based messages and expectations for boys. In addition, understanding whether views vary by population is important for determining the need for audience segmentation in communications campaigns (i.e., targeting unique populations with different messages) or the development or adaptation of programs to better engage parents from different backgrounds (e.g., Noar, 2012).

Method

Recruitment and Data Collection

Thirteen focus group discussions (FGDs) with parents (N=83) of school-age boys (ages 5–9) were conducted from May-June 2020. The original goal aimed to collect data from 12 FGDs, with participants segmented into “rural” or “urban/suburban” groups that aligned with their gender (male, female) and race/ethnicity (Latino/Latina/Hispanic (hereafter referred to as Latino), White, Black), to obtain a range of perspectives across racial/ethnic, gender, and residential categories. However, to ensure sufficient data collection from all participant segments, a thirteenth FGD was conducted with rural White fathers who were underrepresented in recruitment for the initial 12 focus groups. The study focused on parents of school-age boys to ensure participants had experience raising boys through multiple stages of development, and that their experience was current; however, FGDs were not specific to raising school age boys.

FGDs allow researchers to assess and explore the ways in which individuals in a group discuss, debate, and conform around topics and arguments (Hollander, 2004) and have been used extensively in gender norms research. As this was the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, FGDs were carried out via Zoom, lasted 90 minutes, and were facilitated by a trained facilitator whose gender and racial/ethnic background matched the FGD participants.

Parents were recruited via local community-based partners and social media groups (e.g., Facebook, Nextdoor) from one large metropolitan area (urban/suburban) and counties identified as non-metropolitan (rural) using 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes in a Southeastern state. Interested individuals completed an online screening form with demographic (gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, and number, age, and gender of children) and contact information for follow-up. Eligibility for specific groups was based on whether they had a son between ages 5–9, their gender, and their race/ethnicity. Screening forms were completed by 191 respondents; 162 met eligibility criteria and were invited to participate, 121 agreed to participate, and 83 participated. Participants received a $50 gift card. The research protocol was approved by an independent IRB.

Participants

Participants included 83 parents of school-age boys (See Table 1); 56.6% were fathers (M age 38) and 43.4% were mothers (M age = 35). Participants self-identified as White (29%), Black (41%), or Latino (30%) from rural (53.8%) and urban (48.2%) areas. Most participants (82%) were married and 66% had an associate or bachelor’s degree or higher. On average, they had 2.5 sons (range = 1–7) and 1 daughter (range = 0–3).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (n)

| Black | White | Latino | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Total | |

|

| |||||||

| Mothers | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 36 |

|

|

|||||||

| Associate degree or higher | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 25 (69%) |

|

|

|||||||

| Married or living with a partner | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 28 (77%) |

|

| |||||||

| Fathers | 14 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 47 |

|

|

|||||||

| Associate degree or higher | 8 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 26 (55%) |

|

|

|||||||

| Married or living with a partner | 9 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 40 (85%) |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 19 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 83 |

Focus Group Discussion Guide

Facilitators followed a discussion guide that included a combination of direct questions about beliefs and behaviors relating to masculine norms and parenting, and videos from popular media used to facilitate conversations (See Table 2). These videos functioned as vignettes, or short narratives used by researchers to stimulate and contextualize participant responses. Direct and decontextualized approaches such as those employed by typical attitude and social norm qualitative questioning techniques can suffer from social desirability bias and lack contextualization with which to assess responses (Finch, 1987). Vignettes can overcome these limitations by providing a pretext in which to discuss sensitive topics that would be challenging or unethical to address directly (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014), as well as social distance for participants as a buffer against negative emotions associated with these topics (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Focus Group Discussion Guide Structure and Sample Questions

| Activity 1: Defining Masculinity |

|

|

| • Thinking about what you have seen or heard from the media, which of these words [list of words provided in a handout] describe what you think of as an “ideal man” based on what you see in the media? |

| • What does the media tell us about characteristics that an “ideal man” should not be? |

| • When we think of an ideal man—as portrayed in the media, what celebrity or famous person comes to mind? |

| • Now I would like you all to think about your sons and what you want for your sons as they grow up to become men [using the same list]. Can you share one or two of the characteristics/words that you chose? |

| • Were there any words that stood out to you as characteristics that would not be important to you in what you want for your son? Or that you would not want your sons to be like? |

| • Raising boys today can be tough. There are a lot of influences on them, some of which can be hard to protect them from. What aspects of raising boys today make you most concerned? |

|

|

| Activity 2: Gillette commercial 1 |

|

|

| • What are your initial reactions to this commercial? |

| • What do you think the message is? |

| • The commercial ends with this statement “The actions we take today will be seen by the men of tomorrow”? Do you agree with the message? |

| • This commercial was originally aired during the Super Bowl and it led to a lot of different reactions. Some people really liked it and other people did not. Why do you think some people did NOT like this commercial? Do you think this commercial reflects real issues in the U.S.? |

| • Thinking about what is acceptable for men to do or say, what do you think has changed since we were children? |

|

|

| Activity 3: The Mask You Live In trailer 2 |

|

|

| • What are your reactions to this trailer? |

| • The trailer begins and ends with a list of words and phrases that boys might hear. Which of those words or phrases stood out to you the most? [Fathers only: Have you had any of those things said to you? Who said it to you? What were the circumstances?] |

| • Why do you think people communicate these ideas, or messages, to boys? |

| • Based on the trailer, what do you think the point of the movie is? |

| • How do you think these ideas about “being a man” affect boys? |

| • What do you think young boys need from their parents, families, or communities in order to be resilient, or protected, against messages that might be harmful? |

|

|

| Activity 4: Communication Messaging for Parents |

|

|

| • What kinds of information or support do parents need to help protect their sons from potentially harmful messages about what it means to “be a man”? |

| • Like we talked about, some people really did not like [the Gillette] commercial. They said it only showed negative stereotypes about men and most men do not behave that way. What are better ways of talking about this topic? What other ideas do you have about messages and materials that can help start a conversation about this topic? |

Note. Complete discussion guide available from the corresponding author upon request.

We included two videos in our discussion guide: a Gillette commercial that first aired in 2019 (“We Believe”; see https://time.com/5503156/gillette-razors-toxic-masculinity/) and generated substantial online and social media reaction (Bogen, Williams, Reidy, & Orchowski, 2021), and a trailer for the documentary film “The Mask You Live In,” (see https://therepproject.org/films/the-mask-you-live-in/) which depicts the challenges that boys and men in the US face negotiating cultural expectations of masculinity that are harmful to their emotional, physical, and relational health (Newsom, 2015). Using these two videos, we were able to explore participants’ reactions to the arguments put forth in the videos and, through those reactions, better understand their beliefs and norms adherence related to masculinity and parenting sons.

Qualitative Data Analysis

FGD data were transcribed and imported into MAXQDA 2018 Analytics for analysis. Two analysts reviewed each transcript and compiled a list of preliminary descriptive codes both deductively-derived from the literature and guided by the project goals and inductively-derived from the data (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Codes were organized according to a “codebook architecture,” whereby broader organizing categories included a list of smaller codes related to the larger theme. For example, the broader theme of “ideal manhood in the media” includes smaller codes such as “economic characteristics” and “leader.” Codes were iteratively refined and compiled into a codebook that included detailed descriptions of each code, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and examples of the code in use (Bartholow, Milstein, Kathleen, McLellan-Lemal, & MacQueen, 2008). Final codes were then applied to the transcripts by each coder independently with discrepancies discussed to consensus or adjudicated by a third coder when needed.

Data analysis utilized applied thematic analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2011) and narrative analysis (Riessman, 2008) strategies to address the research questions. Analysts used the MAXQDA cross-tabulation feature to generate proportions of code frequencies across transcripts to obtain a “birds-eye view” of code distribution and generate hypotheses around themes to explore further. Analysts then constantly compared codes within and across FGDs and by participant demographics, ultimately arriving at themes, understood to be the “essence of the meaning or experience” (DeSantis & Ugarriza, 2000, p. 355). These themes were mapped using Miro onto axes to tease out their properties, dimensions, and conceptual relationships (Glaser & Strauss, 2017) to ultimately arrive at a more complete understanding. Analysts used analytical memos throughout to document thought processes and questions, and to reflect on the development of ideas (Birks, Chapman, & Francis, 2008). Particular attention was paid to how participants narrated specific beliefs or experiences to identify common narratives that provide insight into the ways in which norms are instilled and communicated in interactions, as well as useful narratives or narrative strategies (e.g., perspectives to adopt; potential referent others) that can inform intervention. The results we present reflect those that manifested via a greater intensity in discussion amongst participants, including how they arrived at conclusions, as well as the attitudes and beliefs expressed by participants in their conversations (Fern, 2001; Barbour, 2005).

Results

Parent Beliefs about Masculinity

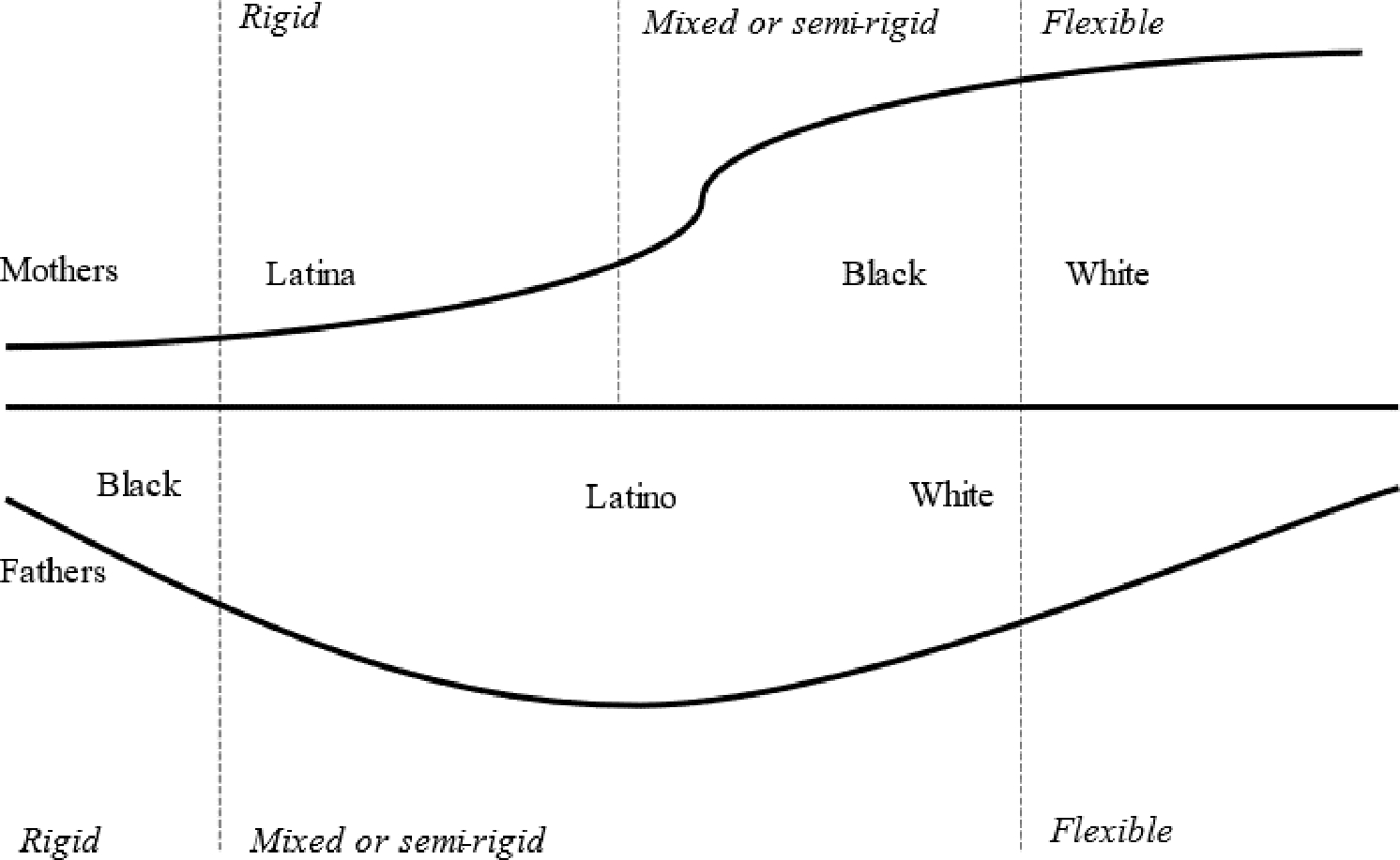

Participants’ beliefs about masculinity existed across a spectrum from “rigid” to “flexible” (see Figure 1). Rigid gender beliefs are those that narrowly define men as in control of themselves, their emotions, and households, and willing to defend their honor physically and metaphorically, aligned with prior conceptualizations and measurement of culturally dominant masculinity norms in the research literature. Parents expressing rigid beliefs endorsed notions that men should be leaders, particularly of their families, with this “head of household” status strongly connected to financial provision. Ideal men were often framed as being effective providers for their family, rather than by their personal traits or behaviors:

Maybe like a real man in our community...would maybe be a construction worker that works all kinds of hours of the day and has to provide for his children. And might even have another job at Kroger. You know, that’s a strong man (rural Latina mother, age 34, married).

Parents expressing rigid gender beliefs also wanted their sons to be “leaders” and “protectors” in adulthood and conceptualized these characteristics as having the emotional strength to resist peer pressure, standing up for one’s beliefs, and being able to financially provide for and guide their family through life’s challenges.

Figure 1. Patterns of Parent Beliefs about Masculinity by Gender and Race/Ethnicity.

Note. Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of patterns observed in qualitative data based on focus group discussions with parents.

Flexible gender beliefs define manhood more broadly, allowing men to engage in a wider range of activities, including those assumed to be traditionally “feminine” such as crying and nurturing one’s children, without compromising their masculine status. These parents acknowledged that a hierarchy exists in broader society between activities considered “masculine” versus “feminine,” and that men experience backlash for engaging in activities considered “feminine.” However, these parents viewed this hierarchy as problematic and described key traits of an ideal man as including respect for women and being able to identify pressures to adhere to harmful masculine norms and intentionally choose an alternative way of being. Parents with flexible gender beliefs wanted their sons to be self-aware, able to navigate harmful social pressures, and to be compassionate towards others: “I would like my son to be a leader, but not a leader that rolls over others or who gets to a position of leadership by dominating others, but rather a leader who is able to influence others... influence others in a positive manner” (urban Latino dad, age 42, married).

The “rigid” and “flexible” gender beliefs represent poles on a spectrum of narrow versus broad gender beliefs. However, many participants expressed gender beliefs that are better located in the central area of the spectrum (mixed or semi-rigid gender beliefs). These parents either expressed a blend of rigid and flexible beliefs or rearranged their comments and arguments as the group discussion progressed or others contradicted their earlier comments. In this way, these expressions reflected norms in practice, whereby individuals re-aligned their reactions and expressed normative beliefs to adhere to norms within the group setting. For example, one father initially argued that the phrase “be a man” imposed harmful restrictions on young boys and that men should reject pressure to adhere to harmful social norms such as fighting to assert dominance, even if “that puts yourself at risk”. However, in response to other fathers who argued that the phrase “be a man” encompasses positive characteristics such as responsibility, work ethic, and accountability, this father amended his response by acknowledging that “the phrase ‘be a man’ isn’t a bad term as long as you have a solid foundation, a solid definition– like a healthy definition of what a man is” (rural White father, age 30, married). Parents with mixed beliefs about masculinity, while expressing a greater range of beliefs, often endorsed notions of an ideal man as a financial provider who cultivates respectful relationships with women and spends time with their sons. These parents endorsed a more traditional model of masculinity wherein men functioned above all as economic providers who instilled work ethic in their sons, while also allowing more space for these men to focus on their emotions and the emotional quality of their relationships with their families.

Demographic differences in expressed gender beliefs:

Overall, mothers expressed more flexible beliefs than fathers, and fewer beliefs at the rigid end of the spectrum. However, among mothers, the more rigid beliefs were primarily expressed by Latina mothers. White and Latino men expressed a wider range of gender beliefs, ranging from mixed or semi-rigid to flexible, while Black men more consistently endorsed rigid to mixed or semi-rigid beliefs (please see Figure 1 for a visual representation of this distribution). No consistent differences were observed between rural and urban groups on the range of beliefs expressed.

Reactions to Masculinity Messaging

Most parents reacted positively to both the Gillette commercial and The Mask You Live In trailer, accepting take-home messages in these videos about how men model or reinforce gender role expectations and the resulting impact on young boys. However, parents in these groups varied in how they framed the issues presented in these videos– as either a gender norms issue, a parenting issue, or—for a smaller number of participants—not an issue that they were concerned with.

Reaction 1: This is a gender norms issue.

Despite the explicit focus of the vignettes on gender socialization, only a portion of participants—more mothers than fathers—recognized the concerns portrayed as gender norms-related. These parents articulated an association between the cultural notion that “real men” are aggressive, dominant, do not cry, and are “in control” (of their incomes, relationships, and emotions) with adverse mental health outcomes:

The concept of the mask that we grow up with is that to be a man, you have to be violent, you have... to silence your emotions, no? And that goes on to generate a lot of unexpressed emotions and many times can lead to suicide and the expressions of violence via school shootings, the use of a guns, for that mask that has been placed on us that doesn’t let us, that sees expressing oneself as unmanly (urban Latino father, age 42, married).

These participants often reacted emotionally to the videos and connected the ideas presented with personal experiences and strategies they have used to teach their sons differently. Several described confronting adults who criticized their sons for behaving in a stereotypically feminine manner (e.g., “wearing pink”; urban Black mother, age 41, married). Others described efforts to support their son’s self-expression, including in ways that conflict with culturally dominant norms (e.g., allowing him to wear a rainbow tutu to his preschool graduation, urban White mother, age 36, married; “trying to instill in my son that it’s okay to cry sometimes”, rural White mother, age 43, married).

Reaction 2: This is a parenting issue.

Other participants who reacted positively to the videos saw the issues presented as parenting challenges, and the problems boys faced—often described as bullying, fighting, or vulnerability to negative peer pressure—reflected a lack of values or good role models that parents are responsible for providing.

What stuck with me was the bullying, and ... that today very few people that when they see bullying, they just stay quiet...That’s what worries me... today it’s more important to grab the phone, record what’s happening instead of putting on the pants and saying, “I’m going to separate this fight, I’m going to defend the weaker person.” Which shows... they’re losing their values, because we as fathers...aren’t teaching our sons good values. (rural Latino father, age 34, married).

These parents felt their sons needed parental emotional support and guidance to navigate the challenges and pressures they face and to avoid the kinds of negative outcomes described by boys in the videos. One mother framed her role as “making sure that they’re compassionate and kind and true to themselves” (urban Black mother, age 35, married) when faced with negative influences.

Reaction 3: This isn’t an issue.

Some parents–the majority of whom were fathers–exhibited resistance to the messages communicated in the videos. Although at least one or two fathers from each group pushed back on the videos, the largest proportion of participants exhibiting resistance to these messages were Black fathers. Non-receptive reactions came in several forms. The most common form was directly challenging the message that masculine norms enforcement and notions of “be a man” were exclusively harmful. For example, when reacting to The Mask You Live In trailer, one father argued:

... “be a man” ... was described as one of the most destructive things a young man ... may hear as a child. It’s not necessarily the most destructive term. He does have to evolve to being a man, at some point in time...we don’t want dads to grow up with their hands out begging all the time just to get through life. They’re going to have to man up at some point (rural Black father, no info).

These fathers argued that notions of “being a man” carried positive and negative assumptions, and the goal was to inculcate positive values in your son, including being a hard worker, a leader, being resilient against negative peer pressure, and being able to take care of himself financially. Several also argued that these messages protected their sons and helped them become strong: “When you hear that around you 24/7, I mean, you either get strong or you give up. One of the two” (rural White father, age 24, married). These fathers did not express concern for the emotional repercussions portrayed in either video, but rather emphasized the need to instill positive masculine norms that would enable their sons to grow into responsible and independent men. Some argued that, in pursuit of being a good man, you may need to be willing to physically defend yourself and your honor. In these ways, they did not demonstrate receptivity to either video’s take-home messages about the ways in which culturally dominant masculine norms could be harmful to their health or well-being.

Beliefs and Reactions by Demographic Group

Mothers versus fathers: Language and mental health.

Some noteworthy trends emerged in attitudes, beliefs, and endorsement of norms between mothers and fathers. Overall, mothers described a greater interest in the impact of language as a means of enforcing harmful masculine norms, such as notions that men should not experience or express certain emotions or that men should resolve conflicts with violence. Although there was variation, most mothers were receptive to the messages conveyed by the Gillette commercial and The Mask You Live In trailer and expressed particular concern about the potential negative mental health outcomes for boys who feel pressured to suppress their emotions or who are unable to express their feelings:

...we’ve cut off our nurturing to our boys at a certain point...because we don’t want to make them too feminine... And that could be part of the anger build-up. ...I’m an educator, I see it on a daily basis with our boys...my husband and I handle (their 8-year-old son) differently. I’m more nurturing and my husband will be the one to be, “Why you crying? You’re not supposed to be crying.” And, you know, all of that. So – but why? Why can’t a boy cry? What’s wrong with that? (rural Black mother, age 34, married).

Many mothers argued that pressure to “be a man” is predominately harmful to boys and efforts should be made to shift society away from these harmful norms and avoid reinforcing them through language. Among mothers who endorsed more flexible models of masculinity– a sizeable portion of the mothers in this study– enforcement of harmful masculine norms was something they felt should be eradicated, allowing boys to behave as children rather than as “men”. They indicated boys should be allowed to cry, behave in “feminine” ways, and ultimately, be allowed to grow into emotionally intelligent men capable of building respectful relationships. Some mothers noted that their more flexible views conflicted with their husband’s perspective, requiring them to negotiate their parenting approach or attempt to counteract the father’s messages:

Me and my husband butt heads a lot when it comes to our son... my husband’s old-fashioned. Men shouldn’t cry, this and that and I’m like why? He’s five!...He feels like well, I’m raising a man! Yeah, you can raise a man when he’s like 13 or 14, not when he’s 5!...That’s really something that I want my son to be able to do, is express his feelings but also be independent and strong, because it’s okay for a man to be able to express his feelings and I want my son to know he can (urban White mother, age 28, married).

Fathers tended to express less concern about the impact of gendered language on boys’ ability to express themselves and the adverse mental health outcomes that may result from emotional suppression. Not surprisingly, those fathers whose reactions suggested that “this [i.e., harmful masculine norms] isn’t an issue” expressed the least concern. Instead, many fathers acknowledged that pressure to “be a man” can impose unrealistic expectations that lead boys and men to experience or participate in bullying, peer pressure, violence, or other negative outcomes. However, unlike mothers, fathers more often believed that this pressure is a social reality that is unlikely to disappear. They posited that boys need to cultivate strategies to navigate this pressure and grow into “good” men with positive attributes, such as being responsible, leaders, having integrity, and being willing to protect others:

Yeah, many times to be accepted within a group you have to look like that. You have to make them respect you... I think that’s true. But with that pattern, you have to know how to handle it. You have to know how to teach them [to handle it]. Because truthfully you can’t let your son become too submissive either, right? But it all has to be done with respect for others (urban Latino father, age 45, married).

Only a few fathers acknowledged their role in potentially reinforcing harmful masculine norms. The majority located the pressure as within peer groups or deriving from media representations. Fathers instead emphasized being positive role models for their sons, helping them cultivate skills to navigate harmful social pressure including pressure to behave aggressively, take irrational risks, or engage in criminal or violent behavior.

Rural versus urban parents.

Contrary to expectations, no meaningful or consistent differences were identified in the discussions between urban and rural groups.

Black parents: Expectations for Black men.

Black participants, both mothers and fathers, explicitly discussed how notions of masculinity differ for Black men compared to other racial/ethnic groups. However, some meaningful differences also emerged between mothers and fathers in their views of masculinity and race. Black mothers discussed how different societal expectations for Black men led to significant limitations on their ability to express emotion, affection, and participate in child-rearing activities. These mothers argued that many Black men perceive expressing or talking about emotions as weakness: “I feel in the Black community, a lot of men are not open to things such as therapy and counseling. Just because I’ve heard men tell me...they don’t need to talk to anybody. They’re not soft” (rural Black mother, age 30, married). Several of these mothers argued that there is more flexibility for White men to express themselves emotionally and contribute to child-rearing activities: “There seems to be a lot more leeway for them to be gentle. For them to be at home. And it doesn’t take away from their manhood” (urban Black mother, age 35, married).

Black fathers also described limitations placed on them by wider expectations about Black masculinity. However, their remarks related to the comparative absence of positive media or popular culture portrayals of middle-class Black men providing for their families. These participants were acutely aware of racially prejudiced assumptions made about Black men and described historical and current strategies to silence their voices, minimize their power, and undermine Black culture:

One of the things historically, and this affects us today, is that for Black men, we’re never allowed to be assertive. Black men were never allowed to be dominant. They were never allowed to be in any kind of power position, historically, in this country. And they were turned into boys by the dominant society. It was okay for a teenage, 17-year-old white boy to see a grown 50-year-old, 40-year-old Black man and say “Hey boy.” And it was accepted in dominant society. And that was feminization. (urban Black father, age 48, not married).

Several Black fathers described feeling concerned about the prejudice and discrimination their sons might face by virtue of their race and efforts they undertook to prepare their sons to be resilient against discrimination:

I told [my son] how I used to get picked on because I was real light skinned... Black folks didn’t like me, white folks didn’t like me. I told him how I changed the narrative for myself by believing in myself and listening to my mentor. When I started listening to my mentor, then I started growing confidence to myself. When I started growing that confidence in myself, then I was able to speak out for myself. And when I was able to speak out for myself, I have things like the [Black Lives Matter] protest now. You know, ... doing different things for my city. But that didn’t come overnight. (rural Black father, age 38, not married).

Latino parents: Changes across generations.

Latino participants, particularly fathers, discussed how expectations of fatherhood have evolved across generations. Some participants discussed how their fathers did not express affection, play with them growing up, or provide essential guidance on important topics (e.g., sex), but rather expected obedience and respect: “...our fathers had a different attitude and way of teaching us. They were very harsh and not very communicative...I had to do what my dad said, in the way he said, at the hour he said” (rural Latino dad, age 34, married). Fathers from this generation, some argued, were expected to provide for their families financially, not emotionally–for example, not spending time with their children or expressing affection for their children. One participant observed that while his father is emotionally expressive, he does not approve of his level of involvement with child-rearing:

...my dad is nice, you know, he gives me hugs and all that, but when I talk to him about some parenting things I do now, he doesn’t get it. He’s like, “why doesn’t your wife do that?” ...He told me once, “I think you’re doing too much in the house. You’re doing too much to help your boys.” It’s like, what? That doesn’t make sense (rural Latino father, age 40, married).

These comments allude to a “traditional” fatherhood model (Vigoya, Fonseca, Latapí, Ferrándiz, & Gutmann, 2002)— one that promotes expectations of fathers as financial providers but not emotional contributors to child rearing—and are consistent with dominant values of machismo in Latin cultures (Nuñez et al., 2016). Participants in the Latino father groups discussed growing up with these cultural ideals modeled in their families but rejecting aspects of it in their own practices. Latino fathers talked more than other father groups about spending time with their sons and doing activities together to build “confianza” (or the feeling of connectedness and trust): “I try to spend time with my son...learn about his interests, what projects he has in his head. I think this helps him to have more confianza with me and tell me what’s going on” (urban Latino father, age 47, married). Some fathers also talked about modeling respectful treatment with their wives to show sons that it is necessary to respect women. Others talked about the need to provide affection and emotional support to their sons because they did not receive this from their fathers and perceived the lack of affection or emotional support to be problematic. Although many Latina mothers expressed more rigid beliefs, those with flexible beliefs echoed Latino fathers’ concerns about overcoming generational differences:

There’s a misconception in the Mexican culture about the man having to be macho and doesn’t need to do house chores. In my house, I teach my kids how to do dishes, the boys and the girls have to do it the same way... I have taught them about doing laundry and everything because I told them: you want to go to college someday... you’re going to live by yourself. I don’t believe in the macho thing... In Mexican culture, it’s so ... difficult to fight that, because the oldest people from the house are like that, the uncles, the grandparents, everything goes like that (urban Latina mother, age 38, married).

White parents.

Discussions in groups with White parents largely echoed those found in other racial/ethnic groups, save for the absence of the unique commentary noted in the Black and Latino groups. White parents, particularly mothers, more often expressed views that clustered towards the “flexible” end of the spectrum of gender beliefs and indicated receptivity towards the messages in both videos. As eliciting unique concerns of White parents was not a primary objective of the current study, additional probing for potential themes was not conducted.

Discussion

Some culturally-dominant masculine gender role norms—prizing stoicism and physical and social dominance over emotional expression and connectedness among men and boys—have been associated with numerous harmful social and health consequences, including increased morbidity and mortality among males related to chronic disease, mental health problems, unintentional injury, and violence (Heilman & Barker, 2018; Heilman et al., 2017; Mahalik et al., 2007). Socialization and enforcement of these “masculine ideals”—through peers, media, culture, and family—not only impacts boys and men but also drives the development of multiple risk behaviors (e.g., aggression, substance use) that are detrimental to public health and safety. Parents and caregivers represent a critical but relatively untapped resource for primary prevention efforts aimed at promoting flexible gender role norms during early and middle childhood, when these beliefs are developing, to reduce negative outcomes. There is growing recognition of the need for such work; for example, gender-responsive parenting is a key component of UNICEF’s Parenting Strategy (UNICEF, 2021a,b). To inform the development of preventative interventions for US parents, the current study conducted FGD with 83 parents of young boys—segmented by gender, race/ethnicity, and rural vs. urban communities—to examine attitudes and beliefs regarding masculine gender role norms, reactions to messages about the potential harms associated with traditional conceptions of masculinity, and the role of gender socialization in raising physically and emotionally healthy boys.

Overall, findings suggest that contemporary parents’ beliefs about masculinity exist across a spectrum from flexible to rigid, with many parents falling in between. On the rigid end of the spectrum, parents saw (ideal) men primarily as leaders and providers who are in control of their emotions and relationships, and willing to defend and protect themselves and others when necessary. Respondents with more flexible conceptions of masculinity believed men could engage in a wide range of behaviors and roles without diminishing their “manhood,” including engaging in activities historically relegated to women (e.g., childcare, housework, emotional labor). However, most parents endorsed a mix of rigid and flexible beliefs. These parents maintained the idea that men should be financial providers with a strong work ethic, but also held a greater expectation for men to be involved parents and respectful partners. Although comparable data are limited, the location of most parents in the center of the spectrum may reflect a gradual and ongoing cultural shift in attitudes. Some research suggests that U.S. adults have reported more egalitarian gender attitudes over time; however, the pace of this change varies by context, with more support for gender equality in the public spheres of work and politics than in the private spheres of home and family (Scarborough et al., 2019). Indeed, despite shifts in attitudes, recent data on US parents’ time use suggests that fathers continue to spend less time with their children compared to mothers (Negraria, Augustine, & Prickett, 2018). Findings from this study also suggest that shifts towards more flexible gender role beliefs vary by demographic and cultural characteristics. Understanding these differences can inform efforts to bolster gender equitable attitudes and reduce the potential harms associated with rigid masculine norms by “meeting people where they are” with messaging that addresses their current beliefs and concerns.

Mothers in this study generally expressed more flexible gender role beliefs than fathers. These findings may reflect the greater gender role flexibility afforded girls and women today compared to males (Miller, 2018). Women are also exposed to masculinity norms indirectly; they see and hear cultural expectations for men but do not face the same potential for social consequences that males may fear, or experience, for nonconformity—potentially resulting in weaker internalization of those norms (Leaper & Friedman, 2007). Indeed, fathers in this study tended to prioritize protecting their sons from perceived threats to achieving “manhood,” at times drawing from their own experiences with the consequences of nonconformity. Such ‘policing of masculinity’ serves a primary means of masculine gender socialization in adolescence and is both normative and potentially harmful (Reigeluth & Addis, 2016, 2021). Aligning with research suggesting that boys’ resistance to masculine norms is associated with greater social and psychological adjustment (Way, 2014), some fathers emphasized the importance of raising sons with the physical and emotional strength to resist social pressures to engage in aggressive or risky behaviors, while also encouraging them to manifest positive masculine characteristics associated with the provider and leader roles. Mothers and fathers may benefit from tailored messaging or interventions addressing their unique perspectives and concerns about parenting boys. For example, many mothers were motivated by concerns for their son’s mental health. Thus, parenting messages focused on supporting boys’ emotional health by encouraging emotional expression and connection may help mothers engage with these ideas and relevant parenting programs.

Cultural norms about gender and parenting are also influenced by the intersecting identities of race and ethnicity (Kane, 2000). Black mothers and fathers in this study pointed to the effects of racism and societal expectations for Black men on their conceptions of masculinity and parenting, with particular concern for the risks associated with perceived weakness. These findings align with “cool pose” theory, which suggests that racial oppression has resulted in a unique conceptualization of masculinity among Black men that emphasizes physical and emotional strength, athleticism, and domination or control of others (Unnever & Chouhy, 2021). Black fathers’ focus on supervision, discipline, and encouragement (versus overt affection) in their parenting practices is also consistent with prior research and may reflect a core interest in promoting their sons’ skills for self-protection (Doyle et al., 2015). Black fathers in this study described the importance of preparing boys to confront these challenges, similar to other research in which Black men viewed perseverance as a critical and positive masculine attribute resulting from exposure to racism-related stress (Hooker et al., 2012). These concerns may explain why some Black fathers reacted negatively to messages framing culturally dominant masculine norms as harmful; to the extent that these norms promote strength in the face of challenges, their perceived benefits may outweigh the risks. Thus, these fathers may respond more positively to prevention messages that acknowledge these concerns and emphasize the ways in which flexible gender beliefs can empower their sons to reject peer pressure and improve their safety and life opportunities.

Many men indicated that their parents, particularly fathers, had more rigid, traditional expectations for their behavior growing up—such as encouraging them to fight, be “tough”, and not cry—than they currently espoused for themselves and their sons. This trend was most evident among Latino men who described a sharp, and salient, contrast between their own beliefs and parenting practices, and those of their fathers. While other groups may have echoed these feelings if asked, Latino fathers discussed these generational changes explicitly and with minimal prompting. As most of these men were first- and second-generation immigrants from Latin America, the contrast between their childhood and adult experiences might be more dramatic or salient (Taylor & Behnke, 2005). This shift might reflect differences in internalization of caballerismo versus machismo constructs among younger generations. Caballerismo emphasizes respect, responsibility for one’s family, chivalry, and the provider role over the aggression, dominance, emotional suppression, and misogyny associated with machismo, with evidence pointing to positive effects on parenting style associated with higher levels of caballerismo beliefs and lower machismo (Mogro-Wilson & Cifuentes, 2021). Related research has also found that Latino boys were more likely than other boys to report moderate to high levels of resistance to masculine norms and to maintain that resistance over time (Way et al., 2014). Way and colleagues suggest that these boys, mostly first- and second-generation immigrants, may less “entrenched” in American norms valuing independence and autonomy and greater internalization of positive Latin cultural values emphasizing family, interdependence, and emotional expression. Many Latina mothers in the current study, in contrast to fathers, expressed more rigid adherence to culturally dominant masculinity norms than Black and White mothers, or Latino fathers. Although not tested in this study, prior evidence suggests lower acculturation among immigrant Latina mothers is associated with more authoritarian parenting practices and an emphasis on traditional values, such as respect for authority (Calzada, Huang, Anicama, Fernandez, & Brotman, 2012); acculturation status might also explain attitudes towards traditional gender roles. More research is needed to understand how acculturation may be affecting Latino men and boys and women differently. However, these findings suggest that parenting interventions focused on Latino parents in the US may benefit from content that addresses cultural and familial influences on their parenting style and provides them with skills to respond to social pressures to parent in ways that do not align with their more flexible beliefs (Barker, Cook, & Borrego Jr., 2010).

Implications for Prevention

Although gender socialization occurs through multiple social and cultural mechanisms, parents and caregivers of young boys are in a unique and critical position to either reinforce or counteract prevailing pressures for boys to internalize traditional masculine norms associated with increased risks for violence, injury, mental health problems, and premature death. Many parents (both mothers and fathers) reacted to video vignettes describing these risks with concern and openness to the core ideas—although concerns were more often framed around mental health, negative peer influences, and bullying than gender. A smaller subset of parents communicated resistance to the idea that enforcing rigid masculinity norms may be harmful to boys and, instead, argued phrases like “be a man” are not inherently harmful when focused on instilling positive values (e.g., work ethic, defense of self and others) and that there may be greater risks associated with nonconformity. Overall, these findings suggest a need for prevention strategies grounded in more complex and nuanced messages about masculinity norms and their relationship to well-being, and that address parents at different points on the spectrum of beliefs. Specifically, these findings suggest a need for two types of interventions:

Promoting social norms change.

Perceived social norms are important drivers of human behavior, and efforts to shift norms— through social marketing, communications campaigns, or social network approaches, for example—have been applied to several health contexts, including substance use, HIV, and violence prevention (e.g., Basile et al., 2016; Burchell et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2022; Sweat et al., 2012). Such approaches may also be useful in shifting masculinity norms towards healthier, broader, and more achievable conceptualizations of “manhood”. Parents at the more rigid end of the spectrum may benefit most from messages that elevate and reinforce positive, flexible examples of masculinity and parenting behaviors that support the socio-emotional health of boys, while also communicating risks associated with culturally dominant norms in terms that acknowledge and address the unique concerns or barriers described across populations. In addition to efforts targeting parents and caregivers directly, approaches that focus on influential adults in the community, such as teachers or faith leaders, can also begin to shift norms within parents’ broader social network, making behavior change easier and more desirable.

Parent training programs.

Many parents in this study expressed concern about the physical and emotional health of boys and an interest in shifting societal expectations and their parenting practices. However, they also described obstacles to changing their behavior to align with these beliefs, such as mothers describing their sons’ fathers endorsing traditional gender roles to the perceived detriment of their sons’ emotional health and development. Adults raised in homes that modeled or enforced traditional gender roles, for example, may lack the skills or behavioral examples to create new dynamics in their own families. Several evidence-based parent training programs exist to teach skills for positive, effective parenting (Fortson et al., 2016). Such content could be integrated into existing parent training programs or new interventions focused specifically on raising healthy boys and tailored to the interests of different communities. Pairing parent training with a communications campaign designed to shift social norms in the surrounding community may also promote parent engagement and bolster effectiveness by exposing participants to reinforcing messages in their environment.

Given the strong theoretical and empirical connections between culturally dominant masculine norms and violence, in particular, it is notable that both social norms-based and parent training approaches have also been identified as effective strategies for the prevention of multiple forms of violence (e.g., Basile et al., 2016; Fortson et al., 2016; Niolon et al., 2017). Building on existing preventative interventions to address healthy masculine socialization in early and middle childhood— along with other risk and protective factors for violence—may accelerate and extend the effects of those interventions to additional health outcomes disproportionately affecting boys and men, as well as the health and safety of the broader community, through cross-cutting prevention efforts.

Limitations and Future Research

Data for this study were collected from parents in urban and rural areas of one Southeastern state using online technologies. These findings may not reflect the beliefs, attitudes, or reactions that would be seen among parents in other geographic areas or who might have been digitally excluded. No notable differences were found between rural and urban parents in this study. This is inconsistent with prior research finding more conservative attitudes among rural than urban men; however, a recent study found that this relationship was moderated by level of education with weaker effects among more educated men (Silva, 2022). As our sample had above average education levels (66% completed some college), the effects of rural vs. urban context on attitudes may have been less evident. This study also included only White, Black, and Latino parents; additional research is needed with other racial/ethnic groups to gain a deeper understanding of their beliefs and receptivity to related parenting messages. In addition, further study with White parents may identify unique concerns or themes that were not elicited in the current study. The high proportion of married parents in this sample may also limit generalizability to single parents, divorced/unmarried co-parents, and other caregivers (e.g., grandparents). Qualitative data can provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of a population than survey or other quantitative data. However, future quantitative research examining parent attitudes and their connection to parenting practices and child outcomes would build on the current findings by identifying evidence-based risk and protective factors in more representative samples to inform the development of parenting and social norms change interventions.

Conclusions

Parents are a primary source of gender socialization in early childhood and an important population of focus for prevention efforts. Although parent attitudes in this study suggest an ongoing shift towards a more flexible understanding of masculinity, many still expressed mixed or rigid expectations for “ideal manhood” that might limit their sons’ life opportunities and health outcomes. Effective efforts to address restrictive conceptualizations of masculinity by reaching parentsand their communities—with social norms change and skills-based interventions have the potential for long-term impacts on numerous costly public health problems, including illness, disease, unintentional injury, and violence. Advancements in the development, evaluation, and dissemination of effective interventions focused on protecting the emotional and physical health of boys will help advance knowledge and practice in this area and has the potential to enhance health equity and improve public health.

Public Significance Statement.

Culturally dominant masculine gender role norms (e.g., emotional stoicism, social and physical dominance, independence, toughness) are associated with negative social and health consequences for boys and men, along with public health and safety concerns related to risk behaviors and violence perpetration. Parents and caregivers of young boys are an ideal target for preventative interventions addressing these norms in early and middle childhood when gender socialization begins. Findings from this study suggest variation by gender and race/ethnicity in contemporary parents’ attitudes towards masculinity and norms-challenging messages about parenting boys, and can inform the development of social norms-based and parenting interventions to improve health equity and address multiple public health concerns, including injury and violence.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for sharing their time and being willing to engage in tough conversations during a particularly challenging time at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors are also grateful for the expertise and partnership of Banyan Communications, Inc. on data collection and interpretation. Funding was provided by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Contract No. HHSD2002015M88152B. Data collection was approved under OMB PRA No. 0920–1050.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose.

Contributor Information

Sarah DeGue, Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Robyn Singleton, Banyan Communications, Inc..

Megan Kearns, Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Aguinis H, & Bradley KJ (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Alemann C, Garg A, & Vlahovicova K (n.d.). The role of fathers in parenting for gender equality. Equimundo. Available from: https://www.equimundo.org/resources/the-role-of-fathers-in-parenting-for-gender-equality/ [Google Scholar]

- Amin A, Kågesten A, Adebayo E, & Chandra-Mouli V (2018). Addressing gender socialization and masculinity norms among adolescent boys: policy and programmatic implications. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(3), S3–S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour RS (2005). Making sense of focus groups. Medical Education, 39(7), 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker CH, Cook KL, & Borrego J Jr (2010). Addressing cultural variables in parent training programs with Latino families. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(2), 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow K, Milstein B, Kathleen M, McLellan-Lemal E, & MacQueen K (2008). Team-based Codebook Development: Structure, Process, and Agreement. In Handbook for Team-based Qualitative Research (pp. 119–135). Rowman AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, DeGue S, Jones K, Freire K, Dills J, Smith SG, & Raiford JL (2016). STOP SV: A technical package to prevent sexual violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS, Reidy D, & Zeichner A (2018). Masculinity, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: A critical review and integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 106–116. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS, Reidy DE, Gentile B, & Zeichner A (2016). Masculine discrepancy stress, emotion-regulation difficulties, and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(6), 1163–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Chapman Y, & Francis K (2008). Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Blazina C, & Watkins CE Jr. (2000). Separation/individuation, parental attachment, and male gender role conflict: Attitudes toward the feminine and the fragile masculine self. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 1(2), 126. [Google Scholar]

- Bogen KW, Williams SL, Reidy DE, & Orchowski LM (2021). We (want to) believe in the best of men: A qualitative analysis of reactions to #Gillette on Twitter. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 22(1), 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J, & Herber O (2014). Vignette development and administration: a framework for protecting research participants. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17(4), 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bradstreet TC, & Parent MC (2018). To be (healthy) or not to be: Moderated mediation of the relationships between masculine norms, future orientation, family income, and college men’s healthful behaviors. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(4), 500. [Google Scholar]

- Burchell K, Rettie R, & Patel K (2013). Marketing social norms: social marketing and the ‘social norm approach’. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang K-Y, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, & Brotman LM (2012). Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JS, Carter SK, & Corra M (2016). The significance of place: The impact of urban and regional residence on gender-role attitudes. Sociological Focus, 49(4), 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, & Zeman J (2007). Influence of gender on parental socialization of children’s sadness regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 210–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, & Zahn-Waxler C (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5(1), 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary A (2012). Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science and Medicine, 74(4), 498–505. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2015). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com/books?id=Dc45DQAAQBAJ [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH (2003). Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. International journal of men’s health, 2(1). [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W (2011). Dying to be Men: Psychosocial, Environmental, and Biobehavioral Directions in Promoting the Health of Men and Boys. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis L, & Ugarriza DN (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly K, Twenge JM, Clark MA, Shaikh SK, Beiler-May A, & Carter NT (2016). Attitudes toward women’s work and family roles in the United States, 1976–2013. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle O, Clark TT, Cryer-Coupet Q, Nebbitt VE, Goldston DB, Estroff SE, & Magan I (2015). Unheard voices: African American fathers speak about their parenting practices. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16(3), 274–283. 10.1037/a0038730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Treves-Kagan S, & Lippman SA (2013). Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: a review of the global evidence. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 2845–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Banyard VL, Waterman EA, Hopfauf SL, Shin H-S, Simon B, & Valente TW (2022). Use of social network analysis to identify popular opinion leaders for a youth-led sexual violence prevention initiative. Violence Against Women, 28(2), 664–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fern Edward F. (2001). Advanced focus group research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Finch J (1987). The vignette technique in survey research. Sociology, 21(1), 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman MA, Buckner JP, & Goodman SH (2000). Gender differences in parent–child emotion narratives. Sex Roles, 42(3), 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, & Alexander SP (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (2017). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon TV, Nichter M, & Henriksen RC Jr (2013). Raising black males from a black father’s perspective: A phenomenological study. The Family Journal, 21(2), 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Graham LM, Embry V, Young BR, Macy RJ, Moracco KE, Reyes HLM, & Martin SL (2021). Evaluations of prevention programs for sexual, dating, and intimate partner violence for boys and men: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(3), 439–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, & Namey EE (2011). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, & Barker G (2018). Masculine Norms and Violence: Making the Connections. Promundo-US. https://promundoglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Masculine-Norms-and-Violence-Making-the-Connection-20180424.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, Barker G, & Harrison A (2017). The Man Box: A study on bring a young man in the US, UK, and Mexico (US P & Unilever, Eds.). [Google Scholar]

- Heilman B, Guerroro-Lopez CM, Rogonese C, Kelberg M, & Barker G (2019). The Cost of the Man Box: A study on the economic impacts of harmful masculine stereotypes in the US, UK, and Mexico - Executive Summary. Promundo US and Unilever. [Google Scholar]

- Heron M (2021). Deaths: Leading Causes for 2019. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JA (2004). The social contexts of focus groups. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 33(5), 602–637. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker SP, Wilcox S, Burroughs EL, Rheaume CE, & Courtenay W (2012). The potential influence of masculine identity on health-improving behavior in midlife and older African American men. Journal of Men’s Health, 9(2), 79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee CS, Takamatsu S, & Gordon D (2011). “Man-ing” up and getting drunk: The role of masculine norms, alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems among college men. Addictive Behaviors, 36(9), 906–911. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, & Smiler AP (2013). Alcohol makes you macho and helps you make friends: The role of masculine norms and peer pressure in adolescent boys’ and girls’ alcohol use. ubstance Use and Misuse, 48(5), 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane EW (2000). Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology, 419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica MS, Benton-Wright S, & Englar-Carlson M (2016). Accentuating positive masculinity: A new foundation for the psychology of boys, men, and masculinity. In Wong YJ & Wester SR (Eds.), APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities (pp. 123–143). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14594-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R, Shoveller JA, Oliffe JL, Gilbert M, Frank B, & Ogilvie G (2012). Masculinities,’guy talk’and ‘manning up’: a discourse analysis of how young men talk about sexual health. Sociology of Health and Illness, 34(8), 1246–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C, & Friedman CK (2007). The socialization of gender. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research, 561–587. [Google Scholar]

- Leone RM, & Parrott DJ (2018). Hegemonic masculinity and aggression. In The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression (pp. 31–42). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Majors RG, & Kelley ML (1998). Masculinity ideology among young African American and European American women and men in different regions of the United States. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4(3), 227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JK, Darmstadt GL, Ashby C, Quandt M, Halsey E, Nagar A, & Greene ME (2020). Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 8(2), e225–e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Burns SM, & Syzdek M (2007). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science and Medicine, 64(11), 2201–2209. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Talmadge WT, Locke BD, & Scott RP (2005). Using the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory to work with men in a clinical setting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC (2018, September 14, 2018.). Many Ways to Be a Girl, but One Way to Be a Boy: The New Gender Rules. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/14/upshot/gender-stereotypes-survey-girls-boys.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur [Google Scholar]

- Mogro-Wilson C, & Cifuentes A Jr (2021). The Influence of Culture on Latino Fathers’ Parenting Styles. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 12(4), 705–729. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, & Stuart GL (2005). A Review of the Literature on Masculinity and Partner Violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(1), 46. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Wright C, & Kaluzny GJSR (2002). If “Boys Will Be Boys,” Then Girls Will Be Victims? A Meta-Analytic Review of the Research That Relates Masculine Ideology to Sexual Aggression. Sex Roles, 46(11), 359–375. 10.1023/a:1020488928736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negraia DV, Augustine JM, & Prickett KC (2018). Gender disparities in parenting time across activities, child ages, and educational groups. Journal of Family Issues, 39(11), 3006–3028. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JS (2015). The Mask You Live In. The Representation Project. [Google Scholar]

- Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J, Rambo K, Irving S, Armstead T, & Gilbert LK (2017). Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM (2012). An Audience–Channel–Message–Evaluation (ACME) Framework for Health Communication Campaigns. Health Promotion Practice, 13, 481–488. 10.1177/1524839910386901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez A, González P, Talavera GA, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Roesch SC, Davis SM, Arguelles W, Womack VY, Ostrovsky NW, Ojeda L, Penedo FJ, & Gallo LC (2016). Machismo, Marianismo, and Negative Cognitive-Emotional Factors: Findings From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Latinx Psycholology, 4(4), 202–217. 10.1037/lat0000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales F, Jarallah Y, & Baxter J (2018). Men’s and women’s gender-role attitudes across the transition to parenthood: Accounting for child’s gender. Social Forces, 97(1), 251–276. [Google Scholar]

- Plan International. (2018). The State of Gender Equality for US Adolescents. https://www.planusa.org/docs/state-of-gender-equality-summary-2018.pdf

- Powers RS, Suitor JJ, Guerra S, Shackelford M, Mecom D, & Gusman K (2003). Regional differences in gender—role attitudes: Variations by gender and race. Gender Issues, 21(2), 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ragonese C, Shand T, & Barker G (2019). Masculine norms and men’s health: making the connections. Promundo-US. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Smith-Darden JP, Cortina KS, Kernsmith RM, & Kernsmith PD (2015). Masculine discrepancy stress, teen dating violence, and sexual violence perpetration among adolescent boys. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(6), 619–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Smith-Darden JP, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Malone CA, & Kernsmith PD (2018). Masculine discrepancy stress and psychosocial maladjustment: Implications for behavioral and mental health of adolescent boys. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(4), 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]