Abstract

The Enterobacter aerogenes eefABC locus, which encodes a tripartite efflux pump, was cloned by complementation of an Escherichia coli tolC mutant. E. aerogenes ΔacrA expressing EefABC became less susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics. Data from eef::lacZ fusions showed that eefABC was not transcribed in the various laboratory conditions tested. However, increased transcription from Peef was observed in an E. coli hns mutant. In addition, EefA was detected in E. aerogenes expressing a dominant negative E. coli hns allele.

During the last decade Enterobacter aerogenes has emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. This gram-negative bacterium is now the third most common pathogen recovered from the respiratory tract and is often isolated in the urine and gastrointestinal tracts (31). E. aerogenes strains isolated from hospitalized patients generally exhibit high resistance levels to a wide variety of antibiotics, including β-lactams, quinolones, chloramphenicol, and tetracyclines (5, 9, 20). In E. aerogenes and other gram-negative bacteria, the decrease of outer membrane permeability and the induction of active drug efflux contribute to multidrug resistance (MDR) (6, 20, 24). The well-studied AcrAB-TolC and MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux pumps are responsible for MDR in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively (18, 26). These pumps belong to the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family (27). RND-type drug efflux pumps share a common three-component organization across the two membranes: a periplasmic linker protein (AcrA, MexA), an inner membrane transporter (AcrB, MexB), and an outer membrane channel (TolC, OprM). The recent elucidations of the crystal structures of TolC and AcrB from E. coli and MexA from P. aeruginosa gave rise to major progress in the understanding of the efflux mechanism in gram-negative bacteria (13, 16, 22).

The entire E. aerogenes genome has yet to be sequenced; therefore, complementation was used to clone the drug efflux systems of E. aerogenes. An E. aerogenes genomic library has previously been screened for complementation of E. coli acrAB or tolC mutants. The E. aerogenes acrAB and tolC loci had been identified, and the AcrAB-TolC pump was shown to contribute to MDR in an E. aerogenes clinical isolate (29). In the present study, we used the same complementation approach to clone a novel multidrug efflux system of E. aerogenes, which we named EefABC (for Enterobacter efflux).

We found that eefABC expression is silent in laboratory growth conditions but induced in both an E. coli hns mutant and an E. aerogenes strain expressing a dominant negative H-NS protein from E. coli.

Cloning of the E. aerogenes eefABC operon and sequence analysis.

We used a genomic library of E. aerogenes BW16627 in the form of a mini-Mu dI5166 lysate to complement E. coli EP663 tolC for growth on plates supplemented with 0.05% deoxycholate (DOC) (11, 29, 34). Among eight recombinant plasmids containing overlapping DNA fragments, we selected pEP770, which carries the shortest insert of about 13.5 kb. E. coli EP665 acrAB tolC was constructed by P1 transduction of EP663 (tolC::Tn10) with a phage lysate prepared on EP661 (ΔacrAB::Kmr). In contrast to acrAB tolC mutants, which are hypersusceptible to hydrophobic compounds (11, 26,34), EP665(pEP770) was able to grow on plates containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 0.1%), DOC (0.05%), novobiocin (3 μg/ml), erythromycin (5 μg/ml), acriflavin (200 μg/ml), or ethidium bromide (10 μg/ml). This suggests that the E. aerogenes DNA insert in pEP770 encodes a complete tripartite efflux pump and not only a TolC homologue. Strains and plasmids used are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| BW5104 | Mu-1 Δlac-169 creB510 hsdR514 | 17 |

| EP661 | BW5104 ΔacrAB::Kmr | 29 |

| EP663 | BW5104 tolC::Tn10 Tcr | 29 |

| EP665 | BW5104 ΔacrAB::KmrtolC::Tn10 Tcr | This work |

| S17.1 λpir | recA thi pro hsdRM+ RP4::2-Tc::Mu::Km Tn7 lysogenized with λ pir phage | 10 |

| PS2209 | Wild type | 4 |

| PS2652 | PS2209 hns-1001 Smr | 4 |

| E. aerogenes | ||

| BW16627 | ATCC 15038 rpsL Smr Ampr | 17 |

| BW16662 | ATCC 15038(pREG2-1, pEG5166S) Cmr | 17 |

| BW16665 | ATCC 15038(pREG2-1, pEG5166S) Cmr | 17 |

| EAEP295 | Nalr derivative of BW16627 | 29 |

| EAEP289 | Kms derivative of the EA27 MDR clinical isolate, Apr Cmr Nalr Smr Tcr | 29 |

| EAEP308 | EAEP289 ΔacrA | 29 |

| EAEP60 | EAEP295 eefA::lacZ Kmr | This work |

| EAEP62 | EAEP289 eefA::lacZ Kmr | This work |

| EAEP64 | EAEP308 eefA::lacZ Kmr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| Mu dI5166 | Mini-Mu for in vivo cloning, Cmr | 12 |

| pEP770 | Mu dI5166 containing eefABC on a 13.5-kb insert, Cmr | This work |

| pBCSK+ | High-copy-number cloning vector, Cmr | Stratagene |

| pDrive | High-copy-number cloning vector, Apr Kmr | Qiagen |

| pEP867 | pDrive containing eefABC on a 6-kb SspI insert, Apr Kmr | This work |

| pVIK112 | pir-dependent oriR6K, suicide vector for lacZ transcriptional fusion, Kmr | 15 |

| pEP872 | pVIK112 containing the eefABC promoter region on a 1.2-kb PstI-SacII fragment, Kmr | This work |

| pGEM-T | High-copy-number PCR cloning vector, Apr | Promega |

| pEP137 | pGEM-T containing the eefABC promoter region on a 0.6-kb insert, Apr | This work |

| pFus2 | Promoterless lacZ cloning vector, Gmr | 1 |

| pUC4K | Source of Kmr cassette | Amersham Biosciences |

| pFus2-K | Kmr Gms derivative of pFus2, obtained by insertion of a BamHI Kmr cassette into the the BglII site of the Gmr gene of pFus2 | This work |

| pMM38 | pFus2-K containing the eefABC promoter region on a 0.6-kb BamHI fragment, Kmr | This work |

| pSU19 | pACYC184 derivative, Cmr | 2 |

| pDIA547 | pSU19 containing the E. coli hns gene, Cmr | 4 |

| pLG339 | Low-copy-number cloning vector, ori-pSC101 Tcr Kmr | 33 |

| pLGH-NSL26P | pLG339 containing an E. coli dominant negative hns allele, Kmr Tcr | 35 |

Apr, Cmr, Gmr, Kmr, Smr, and Tcr, resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline, respectively.

The nucleotide sequence of an 8-kb DNA region from pEP770 was determined and analyzed. Among the six open reading frames identified, the three adjacent, orf3, orf4, and orf5, were found to be homologous to efflux pump genes and were named eefABC. The eef genes are tightly linked and are probably transcribed as an operon. EefA shares 52% and 49% sequence identity with the MexA (P. aeruginosa) and AcrA (E. aerogenes and E. coli) periplasmic linker proteins, respectively. The N-terminal region of EefA exhibits characteristics of a signal sequence including a consensus lipoprotein-processing site (LSGC) (36). EefB shares 56% and 57% sequence identity with the MexB (P. aeruginosa) and AcrB (E. aerogenes and E. coli) inner membrane transporters, respectively. EefC presents 43%, 24%, and 22% sequence identity with the OprM (P. aeruginosa), TolC (E. aerogenes), and TolC (E. coli) outer membrane proteins, respectively. OprM has been shown to be acylated (23), and several P. aeruginosa OprM homologues are predicted to be lipoproteins as they all possess a characteristic lipoprotein box with a conserved cysteine residue immediately downstream of an N-terminal signal sequence (28). EefC contains such a lipoprotein box (CVSL); thus, it may be acylated.

EefABC is an MDR efflux pump in E. aerogenes.

When eefABC was cloned into the pDrive vector downstream from the lac promoter, the resulting plasmid conferred substantial restoration of antibiotic resistance to EAEP308, although not to the levels of the AcrA+ parent strain EAEP289 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Resistance of E. aerogenes strains

| Strain | Diam of growth inhibition (mm)a for drug:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | NFX | CIP | EM | TCb | DOXb | |

| EAEP289, MDR | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 16 | 12 |

| EAEP308(pDrive) | 11 | 11 | 18 | 19 | 27 | 25 |

| EAEP308(pEP867) | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 16 |

| EAEP308(pLG339) | 11 | 11 | 18 | 19 | NDc | ND |

| EAEP308(pLGH-NSL26P) | 8 | 11 | 18 | 14 | ND | ND |

The diameter of the disks is 6 mm. CM, chloramphenicol (30 μg); NFX, norfloxacin (5 μg); CIP, ciprofloxacin (5 μg); EM, erythromycin (15 μg); TC, tetracycline (30 μg); DOX, doxycycline (30 μg). Boldface indicates values significantly different from control values.

The influence of H-NSL26P on tetracycline antibiotic resistance could not be assessed as pLG339 carries a tet gene.

ND, not determined.

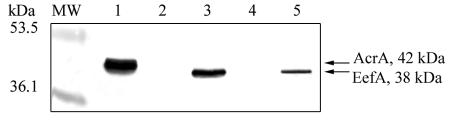

Inner membrane extracts of EAEP308(pEP867) and EAEP308(pDrive) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies raised against E. aerogenes AcrA. A protein of about 37 kDa was detected in the EAEP308(pEP867) inner membrane, but not in that of EAEP308(pDrive) (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 3). This observation suggests that the cross-reactive protein is EefA and that EefA production from the chromosomal eefABC locus is nondetectable in EAEP308.

FIG. 1.

Detection of EefA in E. aerogenes strains. Inner membrane proteins were prepared, and 10 μg was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% acrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunodetected with antibodies raised against E. aerogenes AcrA. Lane 1, EAEP289; lane 2, EAEP308(pDrive); lane 3, EAEP308(pEP867); lane 4, EAEP308(pLG339); lane 5, EAEP308(pLGH-NSL26P).

The eefABC operon is cryptic in laboratory growth conditions.

A suicide plasmid bearing an eefA::lacZ transcriptional fusion was introduced into EAEP295 (BW16627 background), EAEP289 (MDR strain), and EAEP308 (ΔacrA) (15). Integration of the eefA::lacZ suicide plasmid at the eef locus was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. A very weak activity of the reporter fusion was detected in the three resulting strains grown in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C (data not shown). EAEP289 lacks AcrR, the repressor of the acrAB operon; thus, acrAB is overexpressed in this strain (29). The absence of AcrR did not induce eefA::lacZ expression, suggesting that AcrR is not a repressor of eefABC.

Since transcription of multidrug efflux pumps can be induced by the presence of a relevant substrate in the growth medium (19, 30), we tested the effect of various antibiotics, detergents, bile salts, heavy metal salts, solvents, and dyes on the expression level of the eefA::lacZ fusion in EAEP60 (BW16627 background). We also varied temperature, osmolarity, pH, and O2 growth conditions. We found no agent or condition that led to a detectable induction of the reporter fusion (data not shown).

In E. aerogenes, the overexpression of the global regulator MarA or RamA induces an MDR phenotype associated with an increase in AcrA production (7, 8). To decipher whether these efflux activators control eef expression, EAEP60 was transformed with multicopy plasmids bearing marA or ramA. We detected no induction of the reporter fusion when either MarA or RamA was overexpressed (data not shown), suggesting that the eef operon is not part of the MarA and RamA regulatory pathways or is strongly silenced by an upstream repressor.

H-NS is a repressor of eefABC.

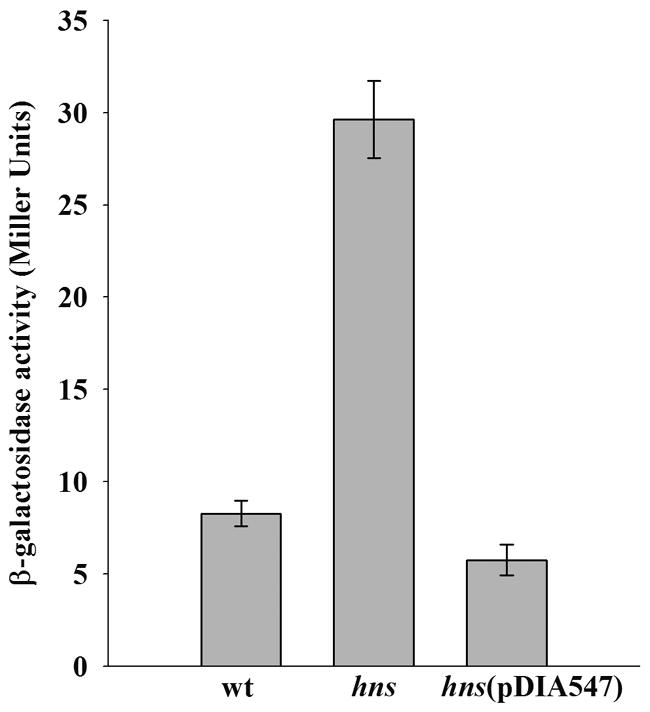

In E. coli, H-NS represses the expression of some multidrug efflux genes and deletion of hns confers MDR to an acrAB-deficient strain (25). We monitored the eef expression in an E. coli hns mutant by using a Peef::lacZ reporter plasmid. The 0.6-kb intergenic DNA region upstream of eefABC (Peef) was PCR amplified by using the primers BamHI-Peef1 (5′ GGA-TCC-TTG-CGT-TTG-GCG-ATA-AGC 3′) and BamHI-Peef2 (5′ GGA-TCC-TGA-GCG-AGG-CGG-TAG-TGC 3′) and E. aerogenes BW16627 genomic DNA as the template. The PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T to obtain pEP137. Digestion of pEP137 with BamHI released the 0.6-kb fragment, which was cloned into the BamHI site of pFus2-K to obtain pMM38, in which Peef controls lacZ expression. The Peef::lacZ expression level increased threefold in the hns mutant compared to the parental strain (Fig. 2). In addition, the Peef::lacZ expression level decreased upon transformation of the hns mutant with a plasmid bearing a wild-type E. coli hns copy. These results suggest that H-NS silences Peef activity in the heterologous host E. coli.

FIG. 2.

Effect of H-NS on the expression of Peef::lacZ in E. coli. Histograms show β-galactosidase activity in E. coli PS2209 (wt), PS2652 (hns), and PS2652(pDIA547) carrying pMM38. β-Galactosidase was assayed on cells cultured overnight (21). The data are expressed as the means of a minimum of three independent experiments. Standard deviations were calculated.

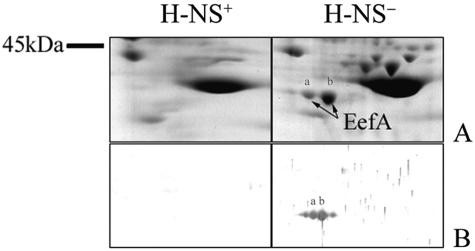

To evaluate the role of H-NS in eef regulation in E. aerogenes, we transformed EAEP308 ΔacrA with pLGH-NSL26P, which carries a dominant negative E. coli hns allele (35). Resistance to chloramphenicol and erythromycin was increased in EAEP308(pLGH-NSL26P) compared to EAEP308(pLG339) (Table 2). However, resistance to fluoroquinolones was not affected. Fluoroquinolones diffuse very efficiently across the bacterial membranes, so it is possible that the fluoroquinolone efflux is too slow to counterbalance entry. To assess EefA production, we analyzed inner membrane extracts of EAEP308(pLGH-NSL26P) and EAEP308(pLG339) by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against E. aerogenes AcrA. A single 37-kDa cross-reactive protein was detected in the inner membrane of the EAEP308 expressing the dominant negative H-NSL26P but not in that of EAEP308(pLG339) (Fig. 1, lanes 4 and 5). Its expression level was 75% lower than that in EAEP308(pEP867) (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 5). To identify this protein, whole-cell membranes of EAEP308 harboring pLG339 or pLGH-NSL26P were prepared and analyzed by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE). The first dimension was carried out on 7-cm isoelectrofocusing strips, pH 3 to 10 NL (Amersham Biosciences), in buffer containing 8 M urea, 2% Triton X-100, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.5% IPG buffer, pH 3 to 10 (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The second dimension was carried out on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide slab gels. Proteins were either visualized with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue staining (Fig. 3A) or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and immunodetected with antibodies raised against E. aerogenes AcrA (Fig. 3B). Two immunoreactive spots (a and b in Fig. 3) were excised from the gel, in gel tryptic digested, and analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (32). In EAEP308(pLGH-NSL26P), an immunoreactive protein was resolved as a major spot of pI 5.3 and an apparent mass of 37 kDa, in agreement with the theoretical values computed from the EefA amino acid sequence. This protein was undetectable in extracts of EAEP308(pLG339) (Fig. 3). The peptide masses were used to search in sequence databases. The MALDI-TOF analysis of tryptic peptides from spots a and b accounted for 28 and 65% coverage of the E. aerogenes EefA precursor sequence tr Q8GC84, respectively, and the matching peptides were distributed throughout the entire sequence (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

2D-PAGE analysis of the membrane protein profiles from EAEP308(pLG339) H-NS+ and its H-NS− derivative expressing E. coli dominant negative H-NSL26P. Equal amounts of proteins (up to 100 μg) from strains to be compared were separated by 2D-PAGE. Proteins were either visualized with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue staining (A) or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and immunodetected with antibodies raised against E. aerogenes AcrA (B). Only the region in the vicinity of the EefA spots is shown. EefA isoforms a and b are indicated by arrowheads.

Conclusions.

Numerous H-NS target genes are involved in bacterial adaptation to stressful environmental conditions and virulence (3, 14). The biological relevance of the eef operon silencing is not known. However, like other commensal or pathogenic bacteria, E. aerogenes has to orchestrate drastic changes in its gene expression profile in order to adapt to the host-associated conditions. Further studies might decipher the regulation and physiological role of the eef operon.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of the E. aerogenes eefABC operon and flanking genes regR (orf 1), act (orf 2), and yfeU (orf 6) have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AJ508047.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Bertin for generously providing strains and plasmids. We also thank Daniel Lafitte for mass spectrometry analysis, Jean-Michel Bolla for critical reading of the manuscript, and Ruth Winter for checking the English.

This work was supported by the Université de la Méditerranée.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoine, R., S. Alonso, D. Raze, L. Coutte, S. Lesjean, E. Willery, C. Locht, and F. Jacob-Dubuisson. 2000. New virulence-activated and virulence-repressed genes identified by systematic gene inactivation and generation of transcriptional fusions in Bordetella pertussis. J. Bacteriol. 182:5902-5905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beloin, C., and C. J. Dorman. 2003. An extended role for the nucleoid structuring protein H-NS in the virulence gene regulatory cascade of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 47:825-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertin, P., E. Terao, E. H. Lee, P. Lejeune, C. Colson, A. Danchin, and E. Collatz. 1994. The H-NS protein is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:5537-5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosi, C., A. Davin-Regli, C. Bornet, M. Mallea, J. M. Pages, and C. Bollet. 1999. Most Enterobacter aerogenes strains in France belong to a prevalent clone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2165-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charrel, R. N., J. M. Pagès, P. De Micco, and M. Mallea. 1996. Prevalence of outer membrane porin alteration in beta-lactam-antibiotic-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2854-2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chollet, R., C. Bollet, J. Chevalier, M. Malléa, J. M. Pagès, and A. Davin-Regli. 2002. mar operon involved in multidrug resistance of Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1093-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chollet, R., J. Chevalier, C. Bollet, J. M. Pages, and A. Davin-Regli. 2004. RamA is an alternate activator of the multidrug resistance cascade in Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2518-2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Gheldre, Y., M. J. Struelens, Y. Glupczynski, P. De Mol, N. Maes, C. Nonhoff, H. Chetoui, C. Sion, O. Ronveaux, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2001. National epidemiologic surveys of Enterobacter aerogenes in Belgian hospitals from 1996 to 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:889-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lorenzo, V., and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5- and Tn10-derived minitransposons. Methods Enzymol. 235:386-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fralick, J. A., and L. L. Burns-Keliher. 1994. Additive effect of tolC and rfa mutations on the hydrophobic barrier of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 176:6404-6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groisman, E. A., and M. J. Casadaban. 1986. Mini-mu bacteriophage with plasmid replicons for in vivo cloning and lac gene fusing. J. Bacteriol. 168:357-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins, M. K., E. Bokma, E. Koronakis, C. Hughes, and V. Koronakis. 2004. Structure of the periplasmic component of a bacterial drug efflux pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:9994-9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hommais, F., E. Krin, C. Laurent-Winter, O. Soutourina, A. Malpertuy, J. P. Le Caer, A. Danchin, and P. Bertin. 2001. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 40:20-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalogeraki, V. S., and S. C. Winans. 1997. Suicide plasmids containing promoterless reporter genes can simultaneously disrupt and create fusions to target genes of diverse bacteria. Gene 188:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koronakis, V., A. Sharff, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, K. S., W. W. Metcalf, and B. L. Wanner. 1992. Evidence for two phosphonate degradative pathways in Enterobacter aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 174:2501-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, X. Z., H. Nikaido, and K. Poole. 1995. Role of mexA-mexB-oprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1948-1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallea, M., J. Chevalier, C. Bornet, A. Eyraud, A. Davin-Regli, C. Bollet, and J. M. Pagès. 1998. Porin alteration and active efflux: two in vivo drug resistance strategies used by Enterobacter aerogenes. Microbiology 144:3003-3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Murakami, S., R. Nakashima, E. Yamashita, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. Crystal structure of bacterial multidrug efflux transporter AcrB. Nature 419:587-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakajima, A., Y. Sugimoto, H. Yoneyama, and T. Nakae. 2000. Localization of the outer membrane subunit OprM of resistance-nodulation-cell division family multicomponent efflux pump in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30064-30068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2004. Role of histone-like protein H-NS in multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:1423-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okusu, H., D. Ma, and H. Nikaido. 1996. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J. Bacteriol. 178:306-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulsen, I. T., M. H. Brown, and R. A. Skurray. 1996. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol. Rev. 60:575-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulsen, I. T., J. H. Park, P. S. Choi, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1997. A family of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane factors that function in the export of proteins, carbohydrates, drugs and heavy metals from gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pradel, E., and J. M. Pagès. 2002. The AcrAB-TolC efflux pump contributes to multidrug resistance in the nosocomial pathogen Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2640-2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg, E. Y., D. Bertenthal, M. L. Nilles, K. P. Bertrand, and H. Nikaido. 2003. Bile salts and fatty acids induce the expression of Escherichia coli AcrAB multidrug efflux pump through their interaction with Rob regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1609-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders, W. E., Jr., and C. C. Sanders. 1997. Enterobacter spp.: pathogens poised to flourish at the turn of the century. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:220-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoker, N. G., N. F. Fairweather, and B. G. Spratt. 1982. Versatile low-copy-number plasmid vectors for cloning in Escherichia coli. Gene 18:335-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitney, E. N. 1970. The tolC locus in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics 67:39-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams, R. M., S. Rimsky, and H. Buc. 1996. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins by using dominant negative derivatives. J. Bacteriol. 178:4335-4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoneyama, H., H. Maseda, H. Kamiguchi, and T. Nakae. 2000. Function of the membrane fusion protein, MexA, of the MexA, B-OprM efflux pump in Pseudomonas aeruginosa without an anchoring membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 275:4628-4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]