Abstract

Novel adulterants and synthetic substances are rapidly infiltrating the US drug supply causing new clinical harms. There is an urgent need for responsive education and training to address these evolving harms and mitigate new risks. Since 2020, xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer, has become increasingly common in the illicit opioid supply, especially alongside fentanyl. Training and technical assistance (TTA) programs employing an adaptive model can quickly disseminate emerging information and provide the tools to respond effectively. We describe our TTA program’s experience developing and delivering virtual instructor-led xylazine training to a diverse group of addiction care professionals. The training objectives included the following: (1) introducing epidemiologic trends, pharmacology, and existing literature related to xylazine; (2) reviewing xylazine-associated harms and management; and (3) discussing harm reduction strategies related to xylazine use. We conducted 14 training sessions between October 2022 and July 2023, which were attended by over 2000 individuals across 49 states. We review our experience developing innovative training content and managing flexible training logistics and highlight our lessons learned, including targeting multidisciplinary professionals, leveraging online synchronous delivery methods, and a need for sustainable funding for TTA programs.

Keywords: xylazine, adulterants, training and technical assistance program, harm reduction, overdose prevention, healthcare providers, wound care

Introduction

Novel adulterants and synthetic substances are rapidly infiltrating the US and international drug supply. Efforts to reduce the overprescription of opioids, compounded by increased pressure from law enforcement, have led to shifts in the US drug market and forced people to seek illicit sources which are at risk of adulteration.1,2 This shifting drug landscape has resulted in an increasingly dangerous and unregulated supply. Initially an adulterant to heroin,3 fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, has now largely replaced heroin as the dominant illicit opioid in the US.4 This shift has resulted in an exponential rise in fatal overdoses and other drug-related harms.5 As the addiction care community continues to navigate the challenges posed by fentanyl, the nation must now adapt to yet another emerging substance, xylazine, contaminating the illicit drug supply.

Xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer, was initially identified as an adulterant to heroin in Puerto Rico during the early 2000s6 and was intermittently detected in the illicit supply prior to 2019.7,8 Since then, xylazine adulteration has expanded across the US at an alarming rate.9 It has been increasingly prevalent in the northeast region, with greater than 90% of opioid drug samples in Philadelphia testing positive for xylazine in 2021.10 From January 2019 to June 2022, deaths involving fentanyl combined with xylazine increased by 276%,11 leading the Office of National Drug Control Policy to declare xylazine-fentanyl an “emerging national drug threat” in 2023.12 However, due to inadequate national drug surveillance and lack of accessible low-barrier drug checking services, real-time knowledge of evolving drug trends is frequently lacking in both persons who use drugs (PWUD) and the providers caring for them.13 As such, the addiction care community can be slow to respond to acute changes in local supplies, often only after noticeable patterns of new or amplified drug-related harms appear or affect larger regions.14

As early as 2020, frontline harm reduction organizations began reporting upticks in “bad bags” to alert their participants to a potential new adulterant, and professionals caring for PWUD began publishing limited reports on clinical harms associated with xylazine use.15–17 However, despite growing concerns among PWUD and those they directly interact with, there was a lack of accessible and adaptive provider training translating extant literature and field experience about xylazine and its clinical implications in caring for PWUD.

Public health threats significantly affect population health, and early effective distribution of information is critical to enhance clinical response capabilities.18,19 In the context of the evolving supply to date, avenues for timely continuing and interprofessional dissemination of information for those in practice have been limited. Providers can seek opportunities for collaborative learning during annual national conferences that require membership or payment; or self-directed learning using emerging literature that requires practical and contextual translation; or rely on freestanding online resources, webinars, or courses, which may exclude the voice of the harm reduction community. Brief, interactive, didactic-based trainings have been effective and are valuable mechanisms to distribute information and implement practices in this field.20 In the rapidly evolving space of new psychoactive substances, peer-reviewed statistical and clinical evidence takes time to accrue. A significant body of current working knowledge from those with lived experience and professional exposure is communicated through professional and informal networks, including social media, and can be used to address urgent and novel substance-related harms. We describe our experience and lessons learned leveraging a robust existing training and technical assistance (TTA) model to disseminate education and information about xylazine as an emerging threat in the absence of robust clinical guidelines and a peer-reviewed evidence base.

Methods

Description of TTA Program

Boston Medical Center’s Grayken Center for Addiction Training and Technical Assistance program (Grayken TTA) utilizes an adaptive, collaborative model to improve care and services for PWUD, by educating, supporting, and building capacity within the addiction workforce. The program provides a range of free and accessible support, training, clinical guidance, and educational resources that are created by clinical and community experts for a global audience. Grayken TTA maintains a comprehensive website (www.addictiontraining.org) that serves as a centralized system for disseminating guidelines and resources, and for scheduling and registering all synchronous and asynchronous TTA activities. Professionals can access multidisciplinary trainings tailored to their background, with free continuing education credits (CEC) for various professions offered for most educational activities. Grayken TTA also manages a large email listserv composed of past training participants, colleagues, national organizations, community leaders, healthcare organizations, and state health departments.

All Grayken TTA educators and collaborators are involved in caring for people with substance use disorder (SUD), PWUD, or their family members. This ensures that new trends, risks, priorities, and gaps in professional knowledge are quickly identified, and resources are developed to meet evolving needs. Grayken TTA is also responsible for supporting the integration of evidence-based addiction treatment into community health centers across Massachusetts21 and other organizations across the country, which results in real-time feedback on urgent issues affecting the addiction workforce. The program frequently sends out needs assessments and asks all training participants what topics they would like to receive education on in the future. Input from those providing direct services is continually reviewed, assessed, and used to inform future educational priorities. A robust training support team provides the infrastructure to efficiently streamline resources and expert educator time, enhancing quality and capacity to deliver to a wide audience.

Description of Xylazine Training

The need for education on xylazine-related harms was highlighted in early 2022 by clinician reports of patients presenting with atypical extremity wounds at infectious disease clinics. Grayken TTA immediately partnered with an addiction medicine clinician who worked alongside the team’s harm reduction specialist with lived experience to co-develop xylazine-specific training content. The objectives of the training curriculum were to: (1) introduce the epidemiologic trends, pharmacology, and extant literature related to xylazine, (2) review xylazine-associated harms (ie, prolonged sedation, withdrawal, impact on overdose risk, and wounds) and management, and (3) discuss potential harm reduction management strategies related to xylazine use. We proactively tailored the training to be applicable to a multidisciplinary audience and have included an example of training content in Supplemental Appendix Table 1.

Innovative Training Content Development and Adaptation

From July to September 2022, the team relied on the limited published domestic literature by clinicians and researchers in Puerto Rico and Philadelphia on xylazine and its clinical effects and harms among PWUD,7,8,22–24 along with nontraditional sources of information for content development. For pharmacology, our team sought literature in veterinary and toxicology sciences and consulted with local specialists in those fields to better understand xylazine and its potential impacts on humans. We leveraged Drug Enforcement Administration, local community drug checking, and medical examiner reports on xylazine adulteration, community-based ecologic studies, and field epidemiologists in our network to present local and national epidemiologic trends. We reviewed relevant clinical case reports and consulted with persons with lived and living experience, frontline providers, harm reduction organizations, outreach wound care nurses, and experts in high prevalence areas to understand xylazine’s clinical effects, harms, and appropriate harm reduction responses. The TTA and session leaders used their long-standing clinical and harm reduction networks to facilitate virtual meetings, phone calls, and pooling of materials to crowdsource local clinical protocols or best practices. Finally, the team proactively scanned social media content on a weekly basis (ie, Reddit forums, YouTube, Twitter, news alerts) to understand the evolving dialogue in the field, community priorities, and clinical questions, as well as identify any inaccurate or hyperbolic information related to xylazine use.

While the training format remained constant over time, the content was continuously updated as new information became available. Examples of updates made include the addition of information on the use of commercially available xylazine test strips,25 modified overdose prevention and response strategies, xylazine withdrawal protocols,26 and wound care best practices.27 The adaptive training content and continuous scoping of emerging information also allowed us to provide counternarratives to emerging media misinformation, stigma, and fear regarding xylazine.28 In addition, the adaptive nature allowed the team to advocate for necessary policy changes, and discuss areas for future research while providing pragmatic strategies to addiction care community professionals to implement in their practice.

Flexible Training Logistics With Post-Training Feedback

We publicized our xylazine training via word of mouth and through the Grayken TTA program’s listserv, website, and social media channels to reach a broad audience. Participants were required to preregister for the training session which typically took place during lunchtime or after business hours to optimize accessibility for working professionals. Each session was co-led by a clinician and a harm reduction expert via Zoom. We provided 1 hour of didactic content and 30 minutes of an interactive open-format question and answer period. A moderator monitored questions asked in the virtual chat. We opted not to record the sessions given rapidly evolving available information about xylazine and to create an environment that allowed participants to candidly ask questions, provide mutual aid, give feedback, and make community connections. A training support team assisted with programming recruitment announcements, managing registration, taking attendance, managing the virtual meeting platform, troubleshooting participant technological issues, providing CEC, and collecting post-evaluation information. Free CEC was offered for physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, social workers, licensed mental health counselors, licensed alcohol and drug counselors, certified alcohol and drug counselors, and recovery coaches. After each training, we distributed the didactic slides and other crowdsourced resources to facilitate opportunities for participants to train others and to share the educational materials. Both formal and informal participant feedback were used to identify content areas that needed further elaboration (eg, the need to create a xylazine wound care-specific training) or educational resources. This feedback resulted in topic experts partnering with Grayken TTA team members to publish freely accessible patient-facing materials for xylazine overdose response29 and wound care30 in English and Spanish and informational public health videos.31–32

Process Evaluation and Quality Improvement

As part of ongoing TTA quality improvement activities, we collected information to help characterize program reach and training impact on practice-level activities and professional knowledge. To assess program reach, we used preregistration participant demographic data (eg, primary professional credential, location of practice, functional role, contact information, type of CEC requested). Given some participants attended the training session multiple times, we removed all duplicate attendees before aggregating and summarizing results. We calculated participants’ region of practice using their state of employment and the US Census Bureau definitions,33 and urbanicity using their employment zip code and the rural-urban commuting area classifications.34 All additional technical assistance requests submitted to Grayken TTA during the time period were documented and summarized by requesting organization type.

A voluntary electronic post-training survey was emailed to each participant to collect feedback and fulfill CEC requirements. Participants received 1 of 2 post-training surveys depending on CEC requested: those requesting continuing medical education (CME) credit (ie, Supplemental Appendix Table 2) versus those seeking non-CME or no CEC (Supplemental Appendix Table 3). To further understand the immediate training impact on attendees’ knowledge, intentions, and attitudes, we conducted a thematic analysis of the following open-response questions: “Please describe at least one change that you plan to make as a result of this activity” (CME survey); “What impact do you predict participation in this educational experience will have in your professional development, practice or on patient outcomes?” (non-CME survey). Open responses to both questions were aggregated and coded using a hybrid inductive and deductive approach. All team members reviewed the open-response evaluation data and an initial framework was developed based on team discussions to guide coding of individual responses. A single reviewer (ASV) was responsible for coding all responses using the framework as a guide and updating as appropriate, as this analysis was conducted for the purpose of quality improvement. All coding was conducted in NVivo (version 14, 2023; Lumivero), and the team reviewed final coding to derive themes.

Results

Training Program Reach

The first xylazine training was in October 2022. Due to high national demand, we continued offering this training once or twice per month. Over a 10-month period, we conducted a total of 14 public virtual instructor-led training sessions, with a median of 182 (interquartile range 153–208) attendees per session and a total of 2312 unique attendees.

In terms of our program reach, participants represented 49 of 50 states, with 61.1% from the northeast region (Table 1). Most participants were practicing in an urban region (88.2%). Slightly more than half (53.1%) of the participants were working in a clinical role. There was considerable diversity in attendees’ professional backgrounds, ranging from clinicians to harm reduction organization personnel to persons with lived experience. Over the course of our trainings, we received over 22 requests for organization-specific TTA from a wide range of sources, primarily from the northeast. Requests for TTA from criminal justice sources included police, fire, jails, prisons, High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas programs, Alcohol and Drug Policy Criminal Justice Subcommittees, including frontline correctional and probation officers, and federal/state/local and tribal agents. Requests from medical sources included local hospitals and SUD programs, community health centers, harm reduction learning collaboratives, addiction task forces, state agencies, tribal working groups, the Providers Clinical Support System, the Opioid Response Network, consulting firms, and emergency medical services.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Xylazine Training Participants from October 2022 to July 2023 (N = 2312a).

| Region, n (%) | |

| Northeast | 1413 (61.1) |

| Midwest | 328 (14.2) |

| West | 289 (12.5) |

| South | 270 (11.7) |

| Outside the US | 10 (0.4) |

| US territory | 2 (0.1) |

| Geography, n (%) | |

| Urban | 2039 (88.2) |

| Rural | 235 (10.2) |

| Not available | 38 (1.6) |

| Primary professional credential,b n (%) | |

| Nurse | 510 (22.1) |

| Recovery support/peer navigator | 485 (21.0) |

| Mental health professional | 362 (15.7) |

| Advanced practice provider | 220 (9.5) |

| Physician | 139 (6.0) |

| Master of public health | 92 (4.0) |

| Allied health professional | 73 (3.2) |

| Student | 52 (2.2) |

| Pharmacist | 44 (1.9) |

| None | 186 (8.0) |

| Other | 149 (6.4) |

| Functional role,c n (%) | |

| Clinical | 1228 (53.1) |

| Administration/management | 394 (17.0) |

| Community/outreach | 295 (12.8) |

| Academia/research | 201 (8.7) |

| Recovery support | 143 (6.2) |

| Other | 51 (2.2) |

| Number of training participants per training,d mean (range) | 183.8 (98–295) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 181.5 (153.3–207.8) |

Unique training participants;

Nurse includes registered nurses (RN), licensed practical nurses (LPN), and nurses with master of science in nursing (MSN), bachelor of science in nursing (BSN), and associates degrees in nursing (ADN). Recovery support/peer navigation includes community health workers, peer recovery coaches, certified alcohol and drug counselors (CADC), licensed alcohol and drug counselors (LADC), certified addictions recovery coaches (CARC), patient navigators, and other addiction counselors. Mental health counselor includes licensed certified social workers (LCSW), licensed independent clinical social workers (LICSW), licensed mental health counselors (LMHC), masters of social work (MSW), and other behavioral health counselors. Advanced practice provider includes nurse practitioners (NP), physicians assistants (PA), clinical nurse specialists (CNS), certified nurse midwives (CNM), and advanced practice registered nurses (APRN). Physician includes doctors of medicine (MD) and doctors of osteopathic medicine (DO). Allied health professional includes medical assistants, occupational therapists, physical therapists, case managers, emergency medical technicians (EMT), paramedics, and phlebotomists. Pharmacist includes doctors of pharmacy (PharmD) and registered pharmacists (RPh).

Clinical includes clinical supervisors, pharmacists, midwives, nurses, case managers, mental health providers, physicians, advanced practice providers, and other clinical staff. Administration/management includes executive leadership, project coordinators, program managers, and other administrative roles. Community/outreach includes community health workers, human services, outreach workers, harm reduction outreach, housing support, and other community service providers. Academia/research includes educators, students, researchers, epidemiologists, analysts, public health professionals, and interns. Recovery support includes recovery coaches, recovery coach supervisors, peer support specialists, recovery specialists, alcohol and drug counselors, and patient navigators.

Based on 14 public trainings; N = 2537 of total participants.

Immediate Impact on Knowledge, Intentions, and Attitudes

Approximately 50% (n = 1253) of unique participants completed the optional post-training survey. We identified 3 major themes related to the impact of the training on knowledge, attitudes, and intended practice changes, professional development, or patient outcomes.

The first theme was an intention to provide education to others, with approximately 45% reporting an intention to disseminate the training information about xylazine-related harms and ways to potentially reduce harm. Numerous participants stated that they hoped to educate patients about xylazine’s presence in the drug supply and its associated harms. Others hoped to disseminate this information to community members, clinical colleagues, and students. One participant said they “will encourage [their] harm reduction counselors to ask about wounds at every encounter and begin to teach participants to wipe needle on clean alcohol pad before injecting.”

The second theme was increased understanding and identification of xylazine-related harms connected to training participation. Some participants had not personally encountered xylazine, and attending this training was the first educational experience they had received; one participant, in particular, felt “better equipped to address issues that arise once we have applicants to our residential program.” While others felt that attending the training complemented and added to their existing knowledge. Numerous participants appreciated the inclusion of content challenging media misconceptions; one participant said, “it was helpful to be aware of the myth of ‘narcan resistance’ and how we will need to adapt our overdose reversal training to the public.”

The third theme was feeling more equipped to respond to xylazine-associated harms in real time. Participants commented that even if they lived in an area where xylazine adulteration was not prevalent, they felt confident about the basics and were better prepared to identify and respond to clinical sequalae affecting their patients. One participant stated that attending the training “will be helpful in [their] response to overdose on site with guests as well as my ability to best advocate for guests or understand what they are experiencing. For example, if we have to provide [naloxone] to a guest and they are not responsive I can encourage staff to focus on rescue breathing.”

Discussion

Our responsive educational training on xylazine had broad reach and impact allowing for timely dissemination of information. By leveraging a flexible TTA model, our team was able to provide accessible education with free CEC to a diverse group of professionals and community members. Post-training participant feedback was critical to facilitate adaptation of content and aid development of needed resources for the field. By pairing information gathered from literature and nontraditional sources with established clinical protocols and harm reduction strategies from the field, we were able to provide tangible education. The added benefit of working with a robust TTA team allowed us to proactively update information in real time that participants could consider implementing in their own practices—all before literature and official public health guidance became accessible.

We noted considerable interest in our training content by participants beyond those with traditional medical backgrounds, including law enforcement, frontline emergency services, firefighters, policymakers, and persons with lived experience. In response, our TTA team adapted training content and created materials that could be utilized by a broad clinical and nonclinical audience.29–32 Furthermore, by having the training co-created and co-led by a person with lived experience alongside an addiction clinician, we demonstrated an example of a meaningful collaboration which is critical in addressing public health impacts of the evolving drug supply. While our xylazine training had a broad reach, we did identify a need for dedicated outreach to facilitate future participation by physicians, specifically, and professionals in rural areas who may also benefit from such educational efforts.

As virtual training has become the norm since the COVID-19 pandemic, we found our online synchronous delivery method utilizing flexible hours to be effective in allowing participation by attendees of numerous disciplines across the US. Through interactive Zoom features, we were able to build a collaborative space where hundreds of participants could interact, share knowledge and resources, create opportunities for peer networking, and receive real-time guidance to address their acute concerns. We were also able to solicit feedback for suggestions for improvement, including additional training topics and ideas for deliverables.

Despite the important service that TTA programs can provide, they often rely on regional, public, or foundational grants, which can limit their reach and sustainability, unlike those that are part of the federally funded network of TTAs that have a national presence. While federally funded TTA programs have broader goals and missions, they also have heterogeneous participation patterns among the addiction care community.35,36 In the age of an evolving drug supply, we ought to consider ways to bolster the efforts of TTA programs that have expertise and are championing innovative content through sustained partnerships and increased federal investment.

As these training sessions were conducted through a single TTA program, our findings and experience may not be generalizable to other TTA platforms. While we included a thematic analysis of open-ended participant responses, the data we reported were derived from evaluation tools in place for quality assurance and CEC purposes, and therefore not designed to assess actual behavior or practice-level change. Additionally, because our thematic analysis was conducted solely for the purpose of quality improvement, we utilized a single coder which could have introduced bias and further limits generalizability.

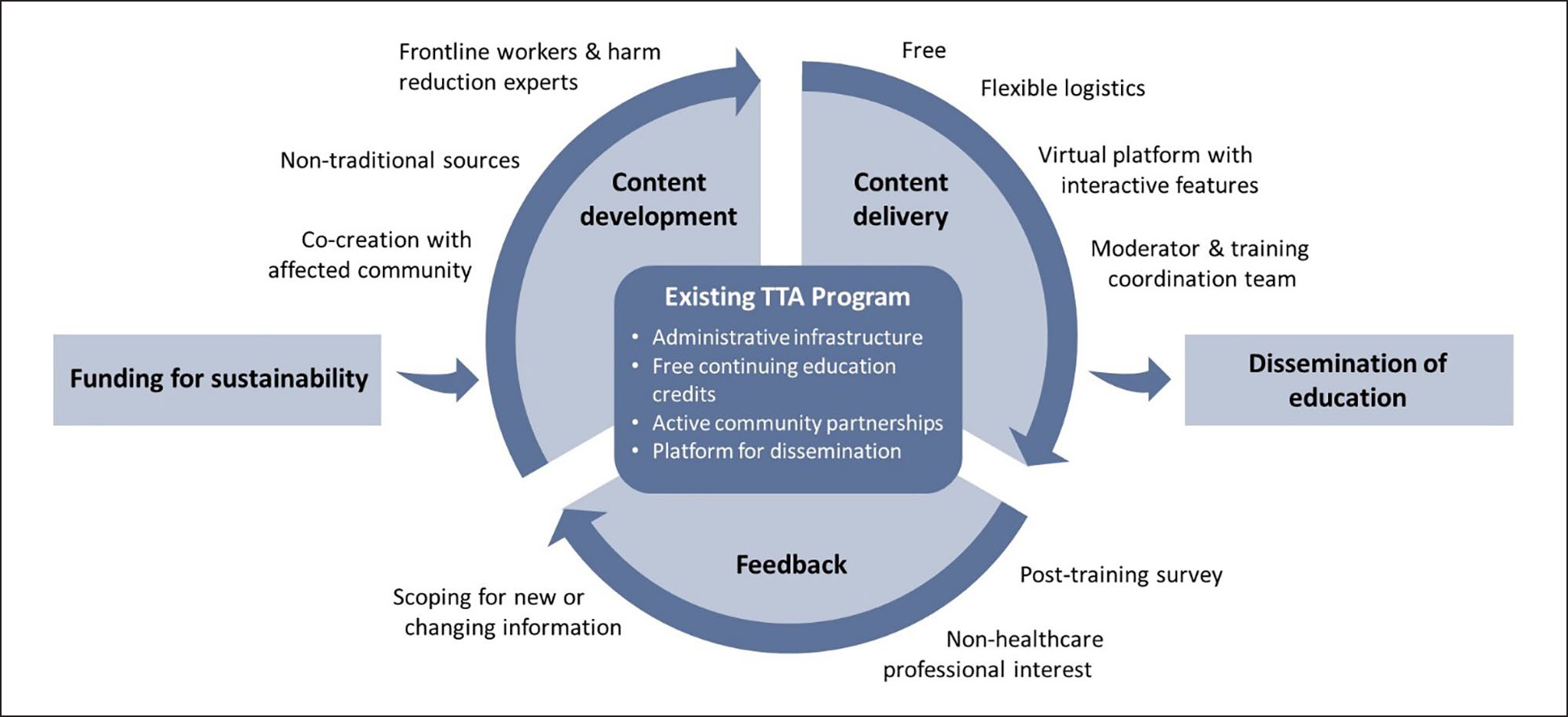

Busy clinical and nonclinical professionals require appropriately delivered education that mirrors the rapidly changing drug supply to address and mitigate drug-related harms. We summarize our lessons learned that could be applied to future adaptive educational trainings for emerging topics (Figure 1) to effectively disseminate real-time pragmatic content to a wide audience. Adaptive educational models have the potential to increase capacity and strengthen the ability of the addiction care community and related stakeholders to address evolving harms associated with the rapidly changing US drug supply. The importance of developing responsive content, recruiting clinical and topic experts, maintaining strong administrative coordination and support, and the ability to offer resources, training, and materials that are freely available to the public cannot be understated.

Figure 1.

Responsive education model leveraging an existing TTA program to address emerging topics. TTA, training and technical assistance.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Novel adulterants, like xylazine, are rapidly infiltrating the US drug supply and causing new clinical harms, resulting in an urgent need for responsive provider training and technical assistance for high-quality information dissemination.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere gratitude goes to the persons who use drugs, frontline harm reduction organizations, advocates and street outreach clinicians, health department epidemiology and drug checking teams, clinicians, and researchers who contributed to the content and evolution of these trainings. We would also like to thank the Grayken Center for Addiction Training and Technical Assistance team who made these trainings possible.

Prior Presentation: Oral abstract presentation at 2023 AMERSA Conference, Washington, DC.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: NIDA K12DA050607 (RJ), MA Department of Public Health Bureau of Substance Addiction Services INTF2330M04500824223 (TTA). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Compliance, Ethical Standards, and Ethical Approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online at the SAJ website http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/29767342241231114.

References

- 1.Beletsky L, Davis CS. Today’s fentanyl crisis: prohibition’s iron law, revisited. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer M, Westenberg JN, Jang KL, et al. Shifting drug markets in North America—a global crisis in the making? Int J Ment Health Syst. 2023;17(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13033-023-00601-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll JJ, Marshall BDL, Rich JD, Green TC. Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island: a mixed methods study. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciccarone D Fentanyl in the US heroin supply: a rapidly changing risk environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahji A, Cheng B, Gray S, Stuart H. Mortality among people with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):e118–e132. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torruella RA. Xylazine (veterinary sedative) use in Puerto Rico. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reyes JC, Negron JL, Colon HM, et al. The emerging of xylazine as a new drug of abuse and its health consequences among drug users in Puerto Rico. J Urban Health. 2012;89(3):519–526. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9662-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SC, Curtis JA, Wingert WE. Concurrent detection of heroin, fentanyl, and xylazine in seven drug-related deaths reported from the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53(2):495–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Drug Enforcement Administration. The growing threat of xylazine and its mixture with illicit drugs. 2022. Accessed October 8, 2023. https://www.dea.gov/documents/2022/2022-12/2022-12-21/growing-threat-xylazine-and-its-mixture-illicit-drugs [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bettigole C, Best A, da Silva DT. Health update: xylazine (tranq) exposure among people who use substances in Philadelphia. Substance Use Prevention and Harm Reduction. 2022. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://hip.phila.gov/document/3154/PDPH-HAN_Update_13_Xylazine_12.08.2022.pdf/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kariisa M, O’Donnell J, Kumar S, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose deaths with detected xylazine—United States, January 2019-June 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(26):721–727. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7226a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. Biden-Harris administration designates fentanyl combined with xylazine as an emerging threat to the United States. 2023. Accessed September 09, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/briefing-room/2023/04/12/biden-harris-administration-designates-fentanyl-combined-with-xylazine-as-an-emerging-threat-to-the-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evrard I, Legleye S, Cadet-Tairou A. Composition, purity and perceived quality of street cocaine in France. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(5):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mars SG, Ondocsin J, Ciccarone D. Sold as heroin: perceptions and use of an evolving drug in Baltimore, MD. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(2):167–176. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2017.1394508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spadaro A, O’Connor K, Lakamana S, et al. Self-reported xylazine experiences: a mixed-methods study of Reddit subscribers. J Addict Med. 2023;17:691–694. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malayala SV, Papudesi BN, Bobb R, Wimbush A. Xylazine-induced skin ulcers in a person who injects drugs in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28160. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman J, Montero F, Bourgois P, et al. Xylazine spreads across the US: a growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;233:109380. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan Y, O’Sullivan T, Brown A, et al. Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1344. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6250-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashcraft LE, Quinn DA, Brownson RC. Strategies for effective dissemination of research to United States policymakers: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01046-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polydorou S, Gunderson EW, Levin FR. Training physicians to treat substance use disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(5):399–404. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0064-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winhusen T, Walley A, Fanucchi LC, et al. The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA): evidence-based practices in the HEALing communities study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108325. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, Viner K. Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010–2019. Inj Prev. 2021;27(4):395–398. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Colon K, Chavez-Arias C, Diaz-Alcala JE, Martinez MA. Xylazine intoxication in humans and its importance as an emerging adulterant in abused drugs: a comprehensive review of the literature. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;240:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López LM, Hermanto J, Russ A, Chassler D, Lundgren LM. Injection of xylazine mixed with heroin associated with poor health outcomes and HIV risk behaviors in Puerto Rico. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(Suppl. 1):A35. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-10-S1-A35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shuda SA, Lam HY. Characterization of xylazine test strips for use in drug checking. 2022. Accessed September 9, 2023. https://www.cfsre.org/images/content/reports/drug_checking/CFSRE_Xylazine_Report-Rev-1-18-23.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy. Best practices for management of xylazine withdrawal and xylazine-related overdose. 2023. Accessed September 09, 2023. https://penncamp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CAMP-Xylazine-Best-Practices-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pennsylvania Department of Health. Xylazine and wound care for healthcare providers. 2023. Accessed September 09, 2023. https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/Documents/Opioids/Xylazine%20Provider%20Info.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canning P Xylazine hysteria. Streetwatch: Notes of a Paramedic. 2023. Accessed September 09, 2023. https://medicscribe.com/2023/03/xylazine-hysteria/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang M, Murray S, Alves J, LaBelle C, Jawa R. (2023). Xylazine Overdose Prevention Pamphlet. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA. (Unpublished): http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/id/eprint/45774. DOI: 10.18117/y2aq-rd48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang M, Murray S, Alves J, LaBelle C, Jawa R. (2023). Xylazine Wound Care Pamphlet. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA. (Unpublished): http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/id/eprint/45776. DOI: 10.18117/gbcq-2w37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jawa R, Blakemore S. Xylazine 101. 2023. Accessed July 07, 2023 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1DEwXoZZ_Qk&t=100s [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jawa R, Blakemore S. Xylazine 102: Focus on Wound Care. 2024. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://youtu.be/fkCWiZtBdr0?si=TJ-KMDy5vqf4Bl3W [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Geographic division or region. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. Acccessed June 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/sources-definitions/geographic-region.htm [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Agriculture. Ag Data Commons user guide. 2010. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafer MS, Oh H, Sturtevant H, Freese T, Rutkowski B. Patterns and predictors of sustained training and technical assistance engagement among addiction treatment and affiliated providers. J Behav Health Serv Res. Published online August 7, 2023. doi: 10.1007/s11414-023-09854-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott K, Salas MDH, Bayles D, Sanchez R, Martin RA, Becker SJ. Substance use workforce training needs during intersecting epidemics: an analysis of events offered by a regional training center from 2017 to 2020. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1063. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13500-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.