Abstract

An association has been observed between systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) in observational studies, however, the exact causal link remains unclear. We aim to evaluate the causal relationships between SLE and PBC through bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR). Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were selected as instrumental variables from publicly accessible genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in European populations. The PBC and SLE GWAS data were obtained from the MRC IEU Open GWAS database, consisting of 24,510 and 14,267 samples, respectively. After a series of quality control and outlier removal, inverse variance weighted was used as the primary approach to evaluate the causal association between SLE and PBC. The horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity were examined by the MR-Egger intercept test and Cochran Q value, respectively. Seven SNPs were included to examine the causal effect of SLE on PBC. Genetically predicted SLE may increase the risk of PBC development, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.324 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.220 ∼ 1.437, P ˂ .001). Twenty SNPs were included to explore the causal effect of PBC on SLE. Genetically predicted PBC may increase the risk of SLE development, with an OR of 1.414 (95% CI 1.323 ∼ 1.511, P ˂ .001). Horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity were absent (P > .05) among SNPs. The robustness of our results was further enhanced by using the leave-one-out method. Our research has provided new insights into SLE and PBC, indicating bidirectional causal associations between the 2 diseases. These findings offer valuable contributions to future clinical studies.

Keywords: Mendelian randomization, primary biliary cholangitis, systemic lupus erythematosus

1. Introduction

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is the most prevalent autoimmune liver disease and is characterized by destructive lymphocytic cholangitis and positive antimitochondrial antibodies. PBC is involved in immunological and cholestatic pathobiological interactions, ultimately resulting in liver cirrhosis progression.[1] The estimated global prevalence of PBC is on the rise.[2] Females and elderly individuals have shown the highest rates of incidence and prevalence.[3] Patients diagnosed with PBC are usually complicated by various extrahepatic manifestations, particularly autoimmune disorders.[4,5] The association between PBC and extrahepatic autoimmune diseases has received considerable scientific attention. In a recent retrospective cohort of 1554 PBC individuals, the prevalence of extrahepatic autoimmune diseases was 28.3%.[6] Although extensive studies have been conducted on the immunological processes that cause liver injury,[7,8] the genetic relationship between PBC and extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is still poorly understood.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multifactorial autoimmune condition with diverse clinical symptoms and can result in life-threatening systemic organ damage.[9] The incidence of SLE varies from 0.3 to 31.5 cases per 100,000 individuals per year and has increased over the past decades.[10] Although the liver is not one of the main organs affected by SLE,[11] 21% of the patients with SLE exhibited abnormal liver function.[12] Furthermore, SLE patients frequently have positive autoantibodies associated with PBC, even in those who do not have elevated liver enzymes.[13] Up to now, PBC and SLE overlap have been observed in some observational studies.[14–17] The co-occurrence of PBC and SLE suggests the possibility of common pathogenic mechanisms.[18,19] However, the causal association between PBC and SLE is still unclear, and further efforts are urgently needed to assess the causality between these disorders.

While traditional observational studies have laid the groundwork for understanding the potential link between PBC and SLE, they face significant limitations when it comes to inferring causality. These limitations include, but are not limited to, confounding factors, reverse causation, and measurement errors. The Mendelian randomization (MR) approach overcomes these limitations by using genetic variants as instrumental variables, which are associated with the exposure of interest but are assumed not to affect the outcome directly, except through this exposure.[20] The advantage of the MR method is that genetic variants are fixed at birth, thus they are not influenced by confounding factors and do not change as a result of the outcome, offering a more reliable means to infer causality. By employing the MR approach, we can more robustly assess whether there is a causal relationship between PBC and SLE, rather than merely an association. In this study, we aim to explore the causal link between PBC and SLE through bidirectional 2-sample MR analysis, indicating bidirectional causal associations between these 2 diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data sources

To eliminate genetic bias due to ethnic differences, the MR analysis was carried out only on the European population. All genome-wide association studies (GWAS) summary data were obtained from the MRC IEU Open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). The GWAS summary data for PBC (ebi-a-GCST90061440) included 8021 cases and 16,489 controls.[21] All cases of PBC were diagnosed based on the criteria for PBC from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The GWAS summary data for SLE (ebi-a-GCST003156) consisted of 5201 cases and 9066 controls.[22] All SLE cases were documented on the basis of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria. All the data in the present study are widely available to researchers worldwide; hence, ethical approval or informed consent was waived.

2.2. Study design

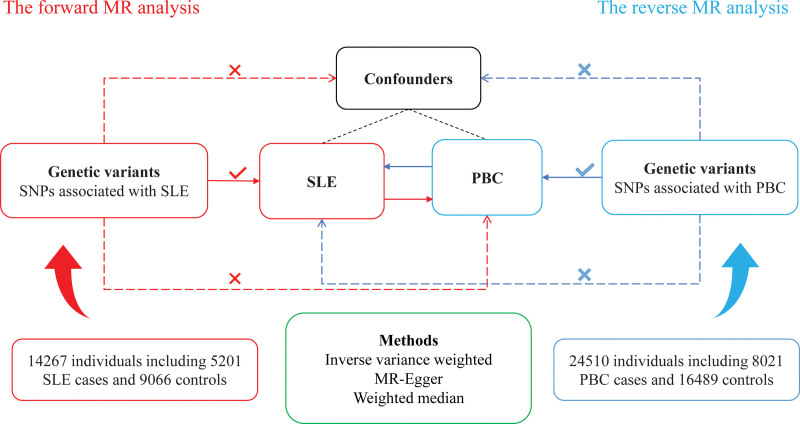

Our MR study employed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables to assess the causal associations between PBC and SLE (Fig. 1). Our study utilized the following 3 presumptions: the SNPs exhibit a strong correlation with exposure; the SNPs are unrelated to numerous confounders; and the SNPs solely affect the outcome through exposure. Therefore, SNPs with genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) were selected. To eliminate bias induced by linkage disequilibrium, SNPs that had a genomic region window of at least 10,000 kb and R2 <0.001 were included. Palindromic SNPs were excluded during SNP selection. The strength of the SNPs was assessed using the F-statistic.[23] SNPs with an F-statistic of <10 were excluded to avoid biasing weak instrumental variables. Confounders were manually retrieved from previous studies in PubMed database.[24–26] The PhenoScanner V2 database (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) was used to screen and exclude SNPs associated with confounders.

Figure 1.

Study design of MR analysis. MR = Mendelian randomization.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The main analysis was performed through the inverse variance weighted (IVW) approach by the TwoSampleMR package to investigate the causal relationships. By aggregating individual ratio estimates, IVW generates overall estimates of the causal influence of exposure on the outcome.[27] The strength of the IVW method lies in its ability to efficiently harness all the available SNPs to calculate the causal effect, proving to be highly effective when all the instruments are valid. MR-Egger regression, on the other hand, is designed to identify and correct for pleiotropy among the instrumental variables. It stands out by offering a causal effect estimate that remains unaffected by pleiotropic effects, under the condition that the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption is met.[28] The weighted median method presents a median-based estimation of the causal effect, emerging as a robust alternative capable of producing valid causal estimates even when as many as 50% of the instrumental variables are invalid.[29] It assigns weights based on the precision of each SNP estimate, striking a balance between precision and resilience against invalid instruments. Each method offers distinct contributions to the robustness and validity of MR analyses. While the IVW method is highly efficient with valid instruments, its susceptibility to pleiotropic effects is notable. MR-Egger addresses the challenge of pleiotropy but at the expense of statistical power and is reliant on the InSIDE assumption for its efficacy. Meanwhile, the weighted median approach provides a middle ground, offering robustness to invalid instruments to a certain extent. The MR results were presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

To ensure that the SNPs were consistent with the basic assumptions of the MR analysis, the possible pleiotropic effects of the SNPs were assessed by the MR-Egger intercept test. The MRPRESSO package is specifically designed to detect and address outliers among the instrumental variables based on the significance of their outlier test P values.[30] After identifying and excluding these outliers, MRPRESSO recalculates the causal estimates, thereby refining the analysis by removing potential sources of bias introduced by pleiotropic outliers. Heterogeneity was quantified by Cochran Q value, and the presence of heterogeneity was determined if the P value was <.05. If there was heterogeneity between the SNPs, the IVW was performed with a fixed effect model; otherwise, the random effect model was applied. In addition, the robustness of the MR results was examined through the leave-one-out approach. This method is instrumental in identifying any individual SNP that disproportionately influences the overall causal estimate, thereby ensuring the reliability of the results. All statistical analyses were performed in R software (version 4.3.1).

3. Results

3.1. Casual effect of SLE on PBC

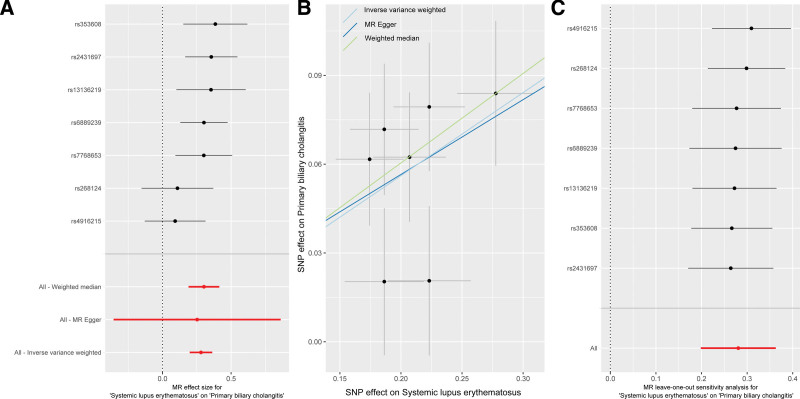

Seven SNPs strongly related to SLE were included to examine the causal effect of SLE on PBC (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/M594). The IVW analysis showed that genetically predicted SLE may increase the risk of PBC (OR = 1.324, P ˂ .001) (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Consistent results were obtained from the weighted median (OR = 1.353, P ˂ .001) (Table 1). The MR-Egger method yielded the same direction of causality (OR = 1.287, P = .45), but did not reach statistical significance. The SNPs included did not show any heterogeneity (P > .05) or horizontal pleiotropy (intercept = 0.006; P = .93) (Fig. 2B, Table 1). The robustness of the MR analysis results was confirmed by the “leave-one-out” method (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Causal effect of SLE on PBC. (A) Estimate effect; (B) scatter plot; (C) “leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis. PBC = primary biliary cholangitis, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 1.

MR results of causal associations between SLE and PBC.

| Exposure to outcome | Methods | OR (95% CI) | P value | Cochran Q (P value) |

MR-Egger intercept (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE to PBC | MR-Egger | 1.287 (0.700–2.366) | .45 | 6.211 (.28) | 0.006 (.93) |

| Inverse variance weighted | 1.324 (1.220–1.437) | <.001 | 6.222 (.40) | ||

| Weighted median | 1.353 (1.211–1.511) | <.001 | |||

| PBC to SLE | MR-Egger | 1.373 (1.140–1.653) | .004 | 27.430 (.07) | 0.008 (.74) |

| Inverse variance weighted | 1.414 (1.323–1.511) | <.001 | 27.602 (.09) | ||

| Weighted median | 1.418 (1.312–1.532) | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval, MR = Mendelian randomization, OR = odds ratio, PBC = primary biliary cholangitis, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

3.2. Casual effect of PBC on SLE

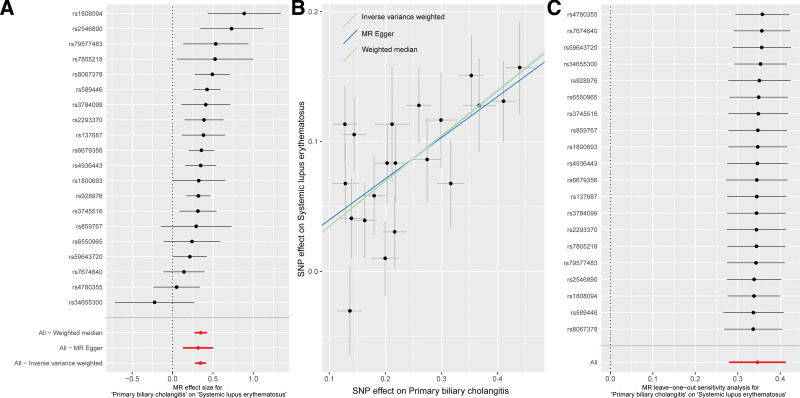

Twenty SNPs strongly related to PBC were included to examine the causal effect of PBC on SLE (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/M595). The IVW method showed that genetically predicted PBC may increase the risk of SLE (OR = 1.414, P ˂ .001) (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Consistent results were also obtained using the MR-Egger (OR = 1.373, P = .004) and weighted median approaches (OR = 1.418, P ˂ .001) (Table 1). No evidence indicated the presence of any heterogeneity (P > .05) and horizontal pleiotropy (intercept = 0.008; P = .74) (Fig. 3B, Table 1). The reliability of the MR analysis was further confirmed through the “leave-one-out” approach (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Causal effect of PBC on SLE. (A) Estimate effect; (B) scatter plot; (C) “leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis. PBC = primary biliary cholangitis, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

4. Discussion

Our study aims to explore the causal relationship between PBC and SLE, a matter that remains unsolved in previous observational studies. Although the potential mechanisms behind SLE and PBC are not yet fully understood, our study has demonstrated a bidirectional causal relationship between the 2 diseases. The robustness of our MR results was validated by sensitivity analysis. Heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy were absent in our study. Our results might suggest a potential overlap in the pathophysiological mechanisms of these autoimmune diseases.

Previous studies showed that the prevalence of concomitant SLE in PBC patients varies between 1.3% and 3.7% and the prevalence of concomitant PBC in SLE patients ranges from 2.2% to 7.5%.[5] SLE patients frequently have positive autoantibodies associated with PBC,[13] while autoantibodies associated with SLE are also often detected in PBC patients.[19] Although the co-existence of PBC and SLE was reported in previous observational studies, the causal associations between these diseases remain unclear. According to the current guidelines for SLE, liver damage is included in the diagnostic and classification criteria for SLE.[10,11] However, abnormal liver function is common in SLE cases.[12] Our study employed the MR approach to evaluate the causal associations between SLE and PBC, showing a bidirectional causal relationship between the 2 diseases. Therefore, except for drug-induced liver injury, the abnormalities in liver function in SLE cases might be caused by PBC.

The development of extrahepatic autoimmune diseases is involved in the interactions of both natural and adaptive immune responses targeting cholangiocytes and various extrahepatic tissues.[31] Smoking has been shown to impair both innate and adaptive immunity and has been identified as a risk factor in developing PBC and SLE.[32,33] Smoking is known to affect pro-inflammatory cytokines mediated Th1/Th17 adaptive immune response, which plays vital roles in the pathogenic mechanisms of PBC.[34] The mechanisms of smoking in SLE is complicated, including effects on abnormal T cell function, evaluated levels of inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress.[35]

There has been a great deal of research about the genetic inheritance of PBC and SLE,[36,37] highlighting the importance of genetic background. Osteopontin is a versatile cytokine and adhesion molecule, which is involved in the regulation of both the innate and adaptive immune responses.[38] Numerous studies have implicated osteopontin in the development of a variety of autoimmune diseases,[38–40] including PBC and SLE. Previous GWAS showed that PBC and SLE shared some common genes, including IL12RB2, IL12A, IL12B, STAT4, CD226, EST1, IRF5, and TNPO3.[14,36,37] These may provide an explanation for why individuals with common genes are more susceptible to concurrent SLE in PBC, or PBC in SLE. Nevertheless, it is challenging to determine the exact mechanism of the above common genes in regulating PBC and SLE. Further comprehension of the genetic heredity of these disorders will be beneficial for clinical pharmacotherapy.

There is growing evidence to suggest that there is a strong link between intestinal dysbiosis and autoimmunity.[41,42] Some research has indicated that individuals with SLE experienced dysbiosis in their gut microbiome, with a reduction in species richness.[43,44] Furthermore, the reduction was more pronounced in SLE patients with high disease activity.[45] Decreased bacterial diversity was also observed in PBC cases, and gut dysbiosis is associated with clinical prognosis.[46,47] Animal studies have shown promising results for gut microbiota-based therapy, supporting the hypothesis that changes in gut microbiota can affect autoimmune responses and disease outcomes.[48] However, the composition of intestinal microflora is frequently influenced by multifactorial conditions, and further study with better design is needed.

Personalized management strategies might be necessary for patients with PBC and SLE, considering the potential shared pathophysiological mechanisms between the 2 conditions. To facilitate early identification and intervention, screening programs for these patients should be detailed and comprehensive. For individuals at risk due to common genetic backgrounds or lifestyle factors, such as smoking, more aggressive monitoring measures are recommended. However, future studies should expand across diverse ethnicities and geographical areas to determine the universality and applicability of these results. Additionally, the integration of advanced omics technologies, such as genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, in future studies could elucidate the molecular pathways shared between PBC and SLE.[49] This might be helpful for the discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Although large samples of GWAS summary data were used for MR analysis, several limitations of this research should be recognized. Firstly, the MR results of this study are derived from the European population. Hence, caution should be taken when extending the results to other ethnic groups. Further analysis and validation of the findings across different populations are imperative. Secondly, both PBC and SLE are more prevalent in females than males. Due to the currently limited GWAS data, stratification of the genetic-level causal effects between PBC and SLE by gender was not possible. Finally, MR analysis only provides the causal association between SLE and PBC, without explanation of the biological process behind the association. Therefore, further experimental efforts are needed to explore the biological mechanism between PBC and SLE.

5. Conclusion

The MR results showed bidirectional causal associations between SLE and PBC, which provides new insights into these diseases and holds significant clinical guidance for clinicians in daily medical practice. Personalized screening protocols should be developed to enhance early detection, facilitating timely therapeutic interventions. Further research is required to assess the universality and applicability of these findings across different ethnic groups and geographical areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the IEU OpenGWAS project for providing GWAS summary data.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ying Wang, Zhe Zhou, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Data curation: Ying Wang, Zhe Zhou, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Formal analysis: Ying Wang, Zhe Zhou, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Methodology: Hai-Ping Zhang.

Software: Ying Wang, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Validation: Zhe Zhou.

Visualization: Ying Wang, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Writing – original draft: Ying Wang, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Writing – review & editing: Ying Wang, Hai-Ping Zhang.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- GWAS

- genome-wide association study

- IVW

- inverse variance weighted

- MR

- Mendelian randomization

- OR

- odds ratio

- PBC

- primary biliary cholangitis

- SLE

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Wang Y, Zhou Z, Zhang H-P. Causal association between systemic lupus erythematosus and primary biliary cholangitis: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Medicine 2024;103:21(e38282).

Contributor Information

Ying Wang, Email: wangyinghy@126.com.

Zhe Zhou, Email: 120695253@qq.com.

References

- [1].Gulamhusein AF, Hirschfield GM. Primary biliary cholangitis: pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Trivella J, John BV, Levy C. Primary biliary cholangitis: epidemiology, prognosis, and treatment. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lv T, Chen S, Li M, et al. Regional variation and temporal trend of primary biliary cholangitis epidemiology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chalifoux SL, Konyn PG, Choi G, et al. Extrahepatic manifestations of primary biliary cholangitis. Gut Liver. 2017;11:771–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang CR, Tsai HW. Autoimmune liver diseases in systemic rheumatic diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:2527–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Efe C, Torgutalp M, Henriksson I, et al. Extrahepatic autoimmune diseases in primary biliary cholangitis: prevalence and significance for clinical presentation and disease outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu SP, Bian ZH, Zhao ZB, et al. Animal models of autoimmune liver diseases: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58:252–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liwinski T, Heinemann M, Schramm C. The intestinal and biliary microbiome in autoimmune liver disease-current evidence and concepts. Semin Immunopathol. 2022;44:485–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kiriakidou M, Ching CL. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fanouriakis A, Tziolos N, Bertsias G, et al. Update omicron the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shen N, Zhao Y, Duan LH, et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2023;62:775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wu CY, Li MC, Duan XW, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with rheumatic diseases and abnormal liver function. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2023;62:1102–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ahmad A, Heijke R, Eriksson P, et al. Autoantibodies associated with primary biliary cholangitis are common among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus even in the absence of elevated liver enzymes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;203:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shizuma T. Clinical characteristics of concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus and primary biliary cirrhosis: a literature review. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:713728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cheng C, Wang Z, Wang L, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus and primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:1819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu Y, Han K, Liu C, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of concomitant primary biliary cholangitis and autoimmune diseases: a retrospective study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:5557814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fan X, Men R, Ni P, et al. Concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus might have a negative impact on the biochemical responses to treatment in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Podgorska J, Werel P, Klapaczynski J, et al. Liver involvement in rheumatic diseases. Reumatologia. 2020;58:289–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Selmi C, Generali E, Gershwin ME. Rheumatic manifestations in autoimmune liver disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44:65–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization. JAMA. 2017;318:1925–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cordell HJ, Fryett JJ, Ueno K, et al.; PBC Consortia. An international genome-wide meta-analysis of primary biliary cholangitis: novel risk loci and candidate drugs. J Hepatol. 2021;75:572–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bentham J, Morris DL, Graham DSC, et al. Genetic association analyses implicate aberrant regulation of innate and adaptive immunity genes in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Burgess S, Thompson SG; CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xiao XY, Chen Q, Shi YZ, et al. Risk factors of systemic lupus erythematosus: an overview of systematic reviews and Mendelian randomization studies. Adv Rheumatol. 2023;63:42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xu H, Wu Z, Feng F, et al. Low vitamin D concentrations and BMI are causal factors for primary biliary cholangitis: a mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1055953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang H, Chen L, Fan Z, et al. The causal effects of inflammatory bowel disease on primary biliary cholangitis: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Liver Int. 2023;43:1741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Floreani A, De Martin S, Secchi MF, et al. Extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune liver disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;59:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Premkumar M, Anand AC. Tobacco, cigarettes, and the liver: the smoking gun. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11:700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Cigarette smoking and autoimmune disease: what can we learn from epidemiology? Lupus. 2006;15:737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yang CY, Ma X, Tsuneyama K, et al. IL-12/Th1 and IL-23/Th17 biliary microenvironment in primary biliary cirrhosis: implications for therapy. Hepatology. 2014;59:1944–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Speyer CB, Costenbader KH. Cigarette smoking and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kwon YC, Chun S, Kim K, et al. Update on the genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: genome-wide association studies and beyond. Cells. 2019;8:1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hitomi Y, Nakamura M. The Genetics of primary biliary cholangitis: a GWAS and Post-GWAS Update. Genes (Basel). 2023;14:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu C, Wu Y, Liu N. Osteopontin in autoimmune disorders: current knowledge and future perspective. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30:385–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wang J, Yuan Z, Zhang H, et al. Obeticholic acid aggravates liver injury by up-regulating the liver expression of osteopontin in obstructive cholestasis. Life Sci. 2022;307:120882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee YH, Song GG. Associations between osteopontin variants and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2023;27:277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chen B, Sun L, Zhang X. Integration of microbiome and epigenome to decipher the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2017;83:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].De Luca F, Shoenfeld Y. The microbiome in autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;195:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. mBio. 2014;5:e01548–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].He Z, Shao T, Li H, et al. Alterations of the gut microbiome in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Azzouz D, Omarbekova A, Heguy A, et al. Lupus nephritis is linked to disease-activity associated expansions and immunity to a gut commensal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:947–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tang R, Wei Y, Li Y, et al. Gut microbial profile is altered in primary biliary cholangitis and partially restored after UDCA therapy. Gut. 2018;67:534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Furukawa M, Moriya K, Nakayama J, et al. Gut dysbiosis associated with clinical prognosis of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatol Res. 2020;50:840–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Miyauchi E, Shimokawa C, Steimle A, et al. The impact of the gut microbiome on extra-intestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tao T, Tang A, Lv L, et al. Investigating the causal relationship and potential shared diagnostic genes between primary biliary cholangitis and systemic lupus erythematosus using bidirectional Mendelian randomization and transcriptomic analyses. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1270401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.