Abstract

Two Bacillus subtilis lysogenic libraries were probed by an antibody specific for a previously described membrane-associated inhibitor of B. subtilis DNA replication (J. Laffan and W. Firshein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7452–7456, 1988). Three clones that reacted strongly with the antibody contained an entire open reading frame. Sequencing identified one of the clones (R1-2) as containing the E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase. An AT-rich sequence in the origin region was identified initially as the site to which extracts from the R1-2 clone were bound. This sequence was almost identical to one detected in Bacillus thuringiensis that also bound the E2 subunit but which was involved in activating the Cry1 protoxin gene of the organism, not in inhibiting DNA replication (T. Walter and A. Aronson, J. Biol. Chem., 274:7901–7906, 1999). However, the exact sequence was not as important in B. subtilis as the AT-rich core region. Binding would occur as long as most of the AT character of the core remained. Purified E2 protein obtained by use of PCR and an expression vector reacted strongly with antibody prepared against the repressor protein and the protein in the R1-2 clone, but its specificity for the AT-rich region was altered. The purified E2 protein was capable of inhibiting membrane-associated DNA replication in vitro, but anti-E2 antibody was variable in its ability to rescue repression when added to the assay.

The role that the bacterial membrane plays in the cell's ability to faithfully replicate its DNA has been the focus of much investigation since the introduction by Jacob et al. of the replicon model (7), which proposed that DNA was attached to the cell membrane and that the site served as a functional unit of organization for DNA replication. The best evidence supporting this model has been (i) the extensive characterization of in vitro replication systems from DNA-membrane complexes extracted from a variety of bacteria, bacteriophages, and plasmid replicons and (ii) recognition that a number of known Dna initiation proteins of these organisms can be extracted from the membrane, may require a membrane environment to function efficiently, or are specifically activated by membrane components (for reviews, see references 3, 4, and 20). Recently, a model proposed by Lemon and Grossman (12) has lent further support to the idea that the replication apparatus (or at least replicative DNA polymerase) does not move along the template but is fixed at a specific site in living cells and that the template is pulled through the DNA polymerase rather than sliding along it (factory model). The fixed site could be of membrane origin.

Nevertheless, if DNA replication is regulated by its membrane association, both positive and negative regulators should be present in the membrane. One such protein was initially detected in Bacillus subtilis by antibody analysis of in vitro membrane-associated DNA replication in which an enhancement (not inhibition) was observed when specific antibody (or its Fab fragments) against an apparent 64-kDa membrane-associated protein was added to the assay (9–11). These results suggested that the protein acted as an inhibitor of such replication and that steric interference in its activity relieved the inhibition. Further results demonstrated that the protein bound strongly to double-stranded DNA within the origin region of B. subtilis (10); that more than one round of semiconservative DNA replication occurred in vitro after the anti-64-kDa antibody was added to DNA-membrane complexes, suggesting that initiation was selectively stimulated (11); and that protease inhibitors added to germinating spores prevented the putative repressor protein (present in spores) from being naturally degraded by proteases, resulting in an inability of such newly germinated cells to initiate a round of DNA replication (2).

In the present study we have cloned the probable gene for this repression and identified it as coding for the E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex, dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids, growth conditions, and plasmid transformation.

Bacillus subtilis strain pLS1 (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Ohio University, Columbus) was used in all experiments involving B. subtilis. Other regions of the B. subtilis chromosome were obtained from the plasmid pMS102′B7 (18). Lysogenic Escherichia coli strain Y1089 containing λgt11 recombinant bacteriophage was used to isolate crude extracts of proteins of the B. subtilis PDH complex. The lysogen clones were originally prepared by Bioserve Biotechnologies (Laurel, Md.) as described below. Luria-Burtani (LB) medium, which contains 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl per liter (13), was used for E. coli growth and plasmid isolation. B. subtilis cells were incubated with Difco antibiotic medium 3. For growing E. coli cells with plasmids, the medium was supplemented with ampicillin at 50 μg/ml. The bacterial cells were incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Plasmid transformation was accomplished by the methods of Hanahan (5), while plasmid DNA was extracted by several methods, one (for small amounts) as described by Maniatis et al. (13) and the second (for larger amounts) with Qiagen columns under the manufacturer's recommended conditions.

Enzyme reactions, including PCR and synthesis of oligonucleotides.

All restriction endonucleases and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from commercial suppliers (Stratagene, New England Biolabs, BRL Life Technologies, US Biochemicals, Sigma, and Boehringer Mannheim) and used according to the manufacturers' recommendations.

When oligomers (oligodeoxynucleotides) were used as probes in experiments, complementary single strands (from BRL) had a 5′ overhang, so the 3′ end could be filled in with radioactive deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates using the Klenow fragment. Two micrograms of each strand was allowed to anneal by boiling it and cooling it to room temperature, after which 2 μl of dCTP and dTTP (1 mM stock) was added, with 2 μl (3 μCi) each of [32P]dATP and [32P]dGTP (150 mCi/ml) and the Klenow fragment, to a total volume of 100 μl. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, the sample was purified by Amicon's microcon tubes according to the manufacturer's directions.

When purified E2 protein was synthesized (see below), oligomers were prepared so that PCR could be used to clone the gene from B. subtilis DNA, which was extracted as described by Marmur (14). Restriction sites (NdeI and BamHI) were designed into the primers to make cloning into Novagen's pET15b expression vector easier. The cocktail (100 μl) for PCR contained a 0.04 mM concentration of each of the four deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, a 1 μM concentration of each primer, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 4 mM MgCl2, and 1 ng of template DNA. The assay was run for 30 cycles in the thermocycler and cooled, protein was extracted with chloroform, and the aqueous layer containing the DNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis before ligation into the pET15b plasmid expression vector.

Gel electrophoresis procedures.

DNA fragments were separated and analyzed by electrophoresis through horizontal agarose gels, with concentrations ranging from 0.8 to 1.5%, depending upon the sizes of the DNA fragments. After being stained with ethidium bromide for visualization under UV light, the bands were cut out of the gel and extracted by the Gene-clean procedure of Qiagen under the manufacturer's recommended conditions.

Proteins were analyzed by electrophoresis through sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide slab gels using the buffer system of Laemmli (8) and were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue. After electrophoresis, the immunodetection of proteins of interest was accomplished by Western blot procedures using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit from Amersham.

Utilization of λgt11 libraries and sequencing.

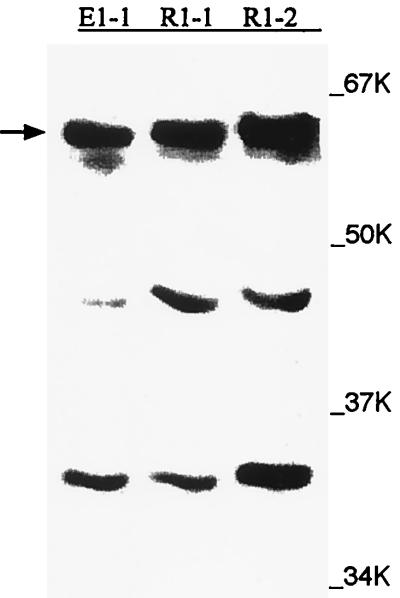

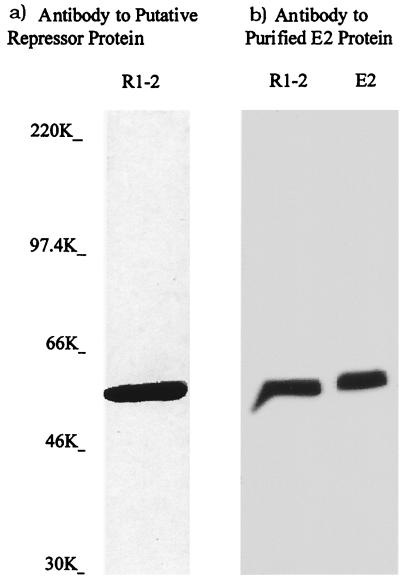

Two B. subtilis λgt11 libraries prepared by Chester Price (21) (one was a random digest created by combining partial digests of AluI, HaeIII, and RsaI, and the other was a partial EcoRI digest) were probed with antibodies directed against the putative repressor (PR) protein (2) by Bioserve Biotechnologies. Of eight lysogen clones that reacted positively by Western blotting, three (one EcoRI digest and two random digests) were chosen for further study because they reacted most strongly with anti-PR protein antibody (Fig. 1). They were sequenced after ligation into a pGem vector (Promega) by Bioserve Biotechnologies.

FIG. 1.

Western blots of λgt11 lysogen clones probed with anti-PR antibody. Lysogenic E. coli strain Y1089 containing two B. subtilis libraries of λgt11 recombinant bacteriophage were obtained from Chester Price of the University of California, Davis (21). Crude protein extracts of those clones that reacted strongly with the anti-PR antibody (2) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The Anti β-galactosidase antibody was obtained from Sigma. The extra bands below 64 kDa are degradation products, since the E. coli vector alone displayed no bands after treatment with anti-PR protein antibody (results not shown).

Preparation of crude extracts from the λgt11 lysogens.

Cultures in LB broth were incubated at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.45 followed by IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction (10 mM) for 1 h at 37°C, freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing, and lysozyme treatment (10 mg/ml) for 15 min on ice. After being centrifuged at 12,000 × g (4°C) for 30 min, the supernatant fluid was dialyzed against a lysogen extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM PMSF [phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride]) and stored at −70°C. This procedure disrupted the membrane and dissociated any membrane-associated proteins into the soluble extract.

Synthesis of purified E2 protein after being cloned into the pET15b expression vector and thrombin cleavage of the His tag.

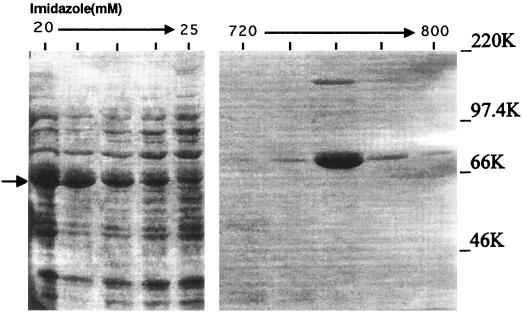

The pET system utilizes an N-terminal His tag sequence in order to purify the fusion protein via a nickel column. After growth of the pET expression vector strain containing the cloned gene in LB medium with ampicillin (50 μg/ml), the cells were centrifuged and the pellets were suspended in a native buffer (50 ml) (20 mM phosphate, pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl), treated with lysozyme (50 μg/ml) for 15 min on ice, and disrupted by sonication; the protease inhibitors leupeptin (1.2 mg/ml) and PMSF (1 mM) were added, and the extract was subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm (20 min; 4°C) in a Sorvall RC2 centrifuge, and the supernatant fluid containing the crude protein was applied to the nickel column as specified by Invitrogen. The pure E2 protein was eluted by stepwise additions of imidazole buffer (20 to 50 mM for early elutions and 600 to 800 mM for later elutions, which yielded the pure protein [see Fig. 4]). Antibodies to the recombinant E2 protein were made by Cocalico Industries (Reamstown, Pa.) for use in some of the experiments. A thrombin cleavage site is encoded by Novagen's pET15b vector. The protease site is placed between the cloning sites of target proteins and the amino-terminal His tag leader sequence. Thrombin cleavage of the purified His-tagged E2 protein was accomplished by adding restriction grade thrombin (2 ng) to the E2 protein (1 μg/ml) in a Tris HCl (pH 8.4) buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O and incubating the mixture for 2 h at room temperature. Cleavage was assayed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

FIG. 4.

Purification of the E2 subunit. B. subtilis strain pLSI from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center was used as the source of chromosomal DNA to clone the E2 subunit gene by PCR amplification into the pET15b expression vector (Novagen). The pET system utilizes an N-terminal His tag sequence fused to the cloned expressed protein to allow purification via a nickel column. The crude protein extract was eluted from the column by increasing stepwise concentrations of imidazole buffer as indicated. Purification was followed by Coomassie blue staining of fractions after SDS-PAGE. All procedures are described in Materials and Methods. The higher-molecular-mass band observed with the highly purified E2 protein is probably a dimer of the protein because it was not observed after dialysis to remove the buffer. Arrow, eluted E2 protein band.

Membrane isolation, preparation for in vitro replication of DNA, and assay.

B. subtilis cells were grown in 1.5 liters of Difio antibiotic 3 medium at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8. They were harvested by centrifugation and washed with HEPES buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 0.1 mM EDTA), and the pellets were resuspended in the same buffer containing potassium glutamate (2 mg/ml), 1 mM PMSF, dimethyl casein (50 μg/ml), 5 mM dithiothreitol, and lysozyme (25 μg/ml) for 5 min on ice. The cells were disrupted at 3,000 lb/in2 for 10 min in a French pressure cell, the debris was removed by centrifuging the solution for 10 min at 8,000 rpm in a Sorvall RC2 centrifuge, and the cloudy supernatant fluid was centrifuged in a Beckman L7 ultracentrifuge for 1 h (4°C) at 45,000 rpm. The resulting pellet was resuspended in the HEPES buffer described above but with 10% glycerol (wt/vol). The crude membrane pellet was then layered on top of a biphasic sucrose gradient (1.35 M sucrose over 1.8 M sucrose) in the same buffer and centrifuged for 18 h at 42,000 rpm (4°C) in a Beckman L7 ultracentrifuge. Two bands (one complexed with ribosomes and the other ribosome free) were observed visually as described by Marty-Mazars et al. (15). The bands were removed, and the free membrane fraction was dialyzed against the glycerol-HEPES buffer for 4 h at 4°C and stored on ice (not frozen) for assay of synthesis within 24 to 48 h.

In vitro membrane-associated synthesis in which no template or enzymes were added was carried out as described previously (9). The purified E2 protein and bovine serum albumin (BSA) control were added at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 37.5 μg/ml.

Gel retardation.

These procedures were carried out as described by Chodosh (1), using a 5% polyacrylamide gel. The samples were prepared by adding 1 μg of poly(dI · dC) (the nonspecific competitor)/ml, 20 to 30 μg of the protein to be bound, and binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol (wt/vol), and 5.0 ng of 32P-labeled oligomer [oligonucleotide] probe) to a total volume of 50 μl. The probe was the last item to be added, and then the mixture was allowed to incubate for 10 min, after which 3 μl of loading dye was added, the mixture was loaded onto the gel, and the gel was run at 4°C (200 V) for approximately 2 h. The running buffer was TBE (0.045 M Tris-borate, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA).

RESULTS

Identification of the PR protein.

In order to determine the identity of the PR protein, two B. subtilis λgt11 lysogens were probed with anti-PR antibody as described in Materials and Methods. At first, it was surprising that all three lysogen clones (one from EcoRI treatment and two from random digests) which reacted strongly with the antibody had molecular masses close to that of the PR protein (64 kDa) (Fig. 1). This is because the λgt11 clones are designed to be fusion proteins in situations where the target clone is adjacent to the lacZ gene and is inducible by IPTG. It would have been expected that the antibody would react with this fusion protein at a much higher molecular mass. However, when anti-β-galactosidase antibody (the product of the lacZ gene) was used as the probe, Western blots showed no detectable high-molecular-mass band on the polyacrylamide gel after induction with IPTG (results not shown). These results suggested that the three clones possessed their own promoter for the PR protein and that they were active in the E. coli cytoplasm. One of these clones (R1-2) was chosen for further study because it demonstrated the strongest antibody reaction (Fig. 1). It was ligated into a pGem vector (Promega) and sequenced, and a GenBank search revealed that it contained a part of the PDH complex of B. subtilis. The only complete gene present in the clone was that for the E2 subunit of the complex, whereas the flanking sequences contained parts of the surrounding genes, namely, those for the E1 and E3 subunits (results not shown). These results led us to conclude that anti-PR antibody recognized the E2 subunit of the PDH complex.

The PDH complex plays a critical role in the citric acid cycle by oxidatively decarboxylating pyruvate to form acetyl coenzyme A. Specifically, the E2 subunit (dihyrolipoamide acetyltransferase) catalyzes the oxidation of the hydroxyethyl group attached to thiamine pyrophosphate to form an acetyl group, which is then transferred to the lipoamide region of E2 and finally to coenzyme A (19). The E2 subunit acts as a symmetrical core around which the other subunits (decarboxylase [E1α and -β] and dehydrogenase [E3]) are arranged stoichiometrically (19). All of the subunits are linked in an operon with the E2 subunit in the middle (6).

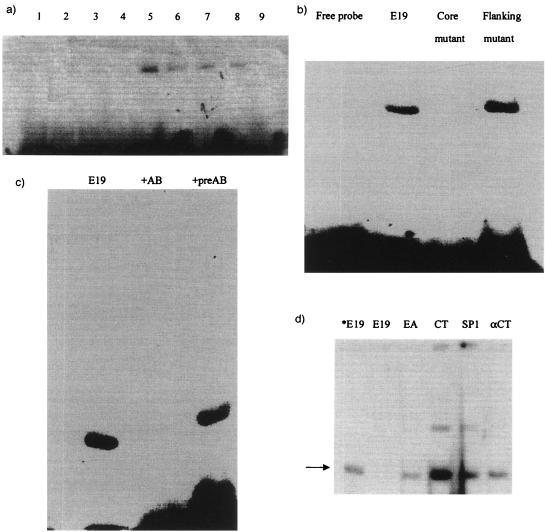

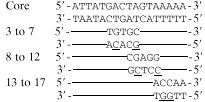

Interaction of the R1-2 clone with an oligodeoxynucleotide from origin region DNA.

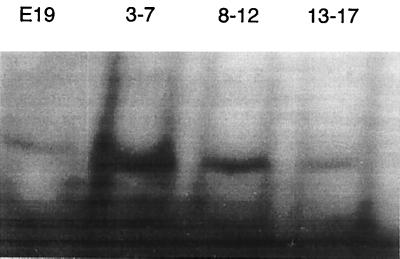

The unexpected observation that the E2 subunit may have a regulatory as well as a catabolic function was further reinforced by the results of Walter and Aronson (22) with Bacillus thuringiensis. The E2 subunit in B. thuringiensis is 88% identical to the B. subtilis E2 subunit and binds to regions upstream of certain (cry) protoxin genes, where it appears to be involved in regulating their synthesis. One of the sequences to which the B. thuringiensis E2 subunit bound was almost identical to a sequence found in a 1.2-kb restriction fragment within the origin region of B. subtilis (E19) (16–18) that bound the PR protein. It is a highly AT rich 17-bp sequence (see the legend to Fig. 2), and this sequence was used in gel retardation experiments with extracts from clone R1-2. A variety of analyses (Fig. 2) demonstrated the following: (i) the AT-rich oligomer probe was retarded by protein extracts from the R1-2 clone but not by λgt11 control preparations (Fig. 2a); (ii) when the central core region of the binding sequence was altered from AT rich to GC rich, binding was prevented, but when the flanking regions were altered with GC base pairs, no effect on retardation was observed (Fig. 2b); (iii) when antibody against the PR protein (which reacts strongly with the R1-2 clone extract) was preincubated with the extract prior to exposure to the oligomer probe, no retardation was observed in comparison to preincubation with preimmune serum (Fig. 2c); and (iv) when various random DNA oligomers were added as nonspecific competitors (100-fold excess) to the gel retardation mixture of the R1-2 extract and radioactive AT-rich probe, only the nonradioactive control probe was capable of competing off the labeled one (Fig. 2d). Although these results indicated that binding of the R1-2 clone extract was specific for the AT-rich sequence in the E19 origin region fragment, two additional experiments suggested that the specific sequence of the AT-rich core region was not as important as its AT rich character. In the first experiment (Fig. 3), three different oligomers, each having approximately one-third of the core region altered with GC base pairs, were tested for their ability to be retarded by the R1-2 protein. The results showed that there was no decrease in binding of any of the altered oligomers to the R1-2 protein, and in fact, one of the altered oligomers (bases 3 to 7) displayed an enhancement in binding intensity compared to that of the control. In the second experiment, the AT-rich core was rearranged, leaving its AT-rich character intact. No difference in binding of the R1-2 protein was detected (results not shown).

FIG. 2.

Interaction of extracts from the R1-2 clone with an oligomer fragment from the origin region of B. subtilis. Gel retardation techniques were used to ascertain whether the protein extracts interacted with the oligomer from the E19 fragment as described previously (1) and in Materials and Methods. This fragment in B. subtilis contained the following 17-base sequence: 5′-ATTATGACTAGTAAAA-3′. The concentrations of extracts, the 32P-labeled oligomers, and their preparation are described in Materials and Methods. (a) Gel retardation of the labeled oligomer probe with R1-2 lysogen and control extracts. Lanes 1 to 4 are various concentrations of lysogen control (20 to 5 μg), while lanes 5 to 8 are R1-2 extracts (20 to 5 μg). Lane 9 is the labeled E19 oligomer probe alone. (b) Gel retardation of different labeled oligomer constructions with the R1-2 lysogen extracts. The native E19 oligomer probe was modified by changing the core (underlined) or the flanking sequences as follows:Native 5′-CATGACCATTATGACTAGTAAAAA-3′3′-TAATACTGATCATTTTTGAAAAA-5′Core 5′-CATGACCCGGCGACTGCAGCCCCC-3′3′-GCCGCTGACGTCGGGGGTGAAAAA-5′Flanking 5′-TCGACTTATTATGACTAGTAAAAA-3′3′-TAATACTGATCATTTTTGACCCCC-5′(c) Gel retardation of the labeled E19 oligomer probe with R1-2 lysogen extracts pretreated with anti-PR protein antibody (+AB) or preimmune serum (preAB). (d) Gel retardation of the labeled E19 oligomer probe with R1-2 lysogen extracts in the presence of various unlabeled nonspecific oligomers from chicken embryos and the unlabeled oligomer probe. *E19 is a control without addition of any unlabeled probe. E19 represents the mobility shift in the presence of a 100-fold excess of unlabeled E19 oligomer. EA, CT, SP1, and αCT represent the mobility shifts with 100-fold excess of unlabeled chicken embryo oligomers. Arrow, retarded band.

FIG. 3.

|

Taking all of the results together, it is believed that there is not a strict sequence necessary for binding of the core AT-rich region to the R1-2 protein in B. subtilis but that as long as the sequence is strongly AT rich, there probably will be an interaction. Whether a consensus binding sequence is involved in the binding, as with B. thuringiensis (22), is not known.

Purification of the E2 subunit.

In order to confirm that the PR protein in the R1-2 clone was, in fact, the E2 subunit and that its activities were due only to this subunit, the E2 protein was purified as described in Materials and Methods. The PCR product of the E2 gene from B. subtilis chromosomal DNA was cloned into the Novagen pET-15b cloning vector, and purification was achieved by fractionation of the His-tagged expressed protein using nickel column chromatography. One fraction from the column yielded a highly purified protein of the appropriate molecular mass as seen on Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 4). It should be pointed out, however, that according to the E2 gene sequence, the molecular mass is 48 rather than 64 kDa (6). This discrepancy is thought to be due to its slower migration on polyacrylamide gels (6). Western blot analysis confirmed that the isolated protein is the E2 subunit (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Western blots with anti-PR protein antibody and anti-E2 antibody. (a) anti-PR protein antibody reacting with protein extract of the R1-2 clone; (b) anti-E2 antibody reacting with the R1-2 clone extract and purified E2 protein.

Gel retardation experiments with the E2 protein and the AT-rich oligomer proved only partially successful. There was clearly a band shift with the E2 protein and the native oligomer probe, but specificity seemed to be lost in that the core mutant, as well as the native probe, was retarded, in contrast to its failure to be retarded by the R1-2 extract (results not shown). Adding cell lysates from control cells that may have contained a cofactor for proper activity, or removing the 6-amino-acid His tag by thrombin treatment, did not restore specificity (results not shown).

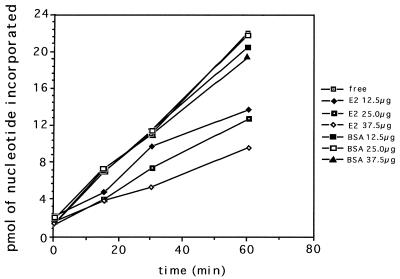

Effects of the purified E2 protein on membrane-associated DNA replication.

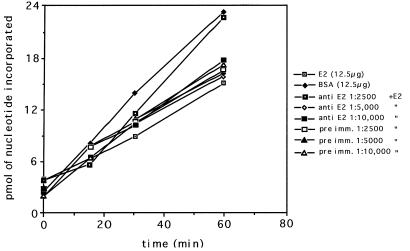

In order to illustrate the biological activity of the E2 protein, an in vitro membrane-associated DNA replication system described previously (9) and in Materials and Methods was assayed in several ways. First, addition of the purified E2 recombinant protein to the assay system should have tested the idea that the protein does indeed act as a DNA replication inhibitor. Second, attempts were made to rescue this repression of replication (if it occurred) through steric hindrance of the E2 protein by specific anti-E2 antibody. Third, addition of anti-E2 antibody to the membrane-associated DNA replication system should have stimulated DNA replication just as the original antibody to the PR protein did (11). Of the three approaches, only the first worked unequivocally (Fig. 6). The results confirmed that there was a significant inhibition of membrane-associated DNA replication with the addition of increasing amounts of E2 protein. The control in these experiments was BSA prepared in the same buffer and concentration as the E2 protein. However, attempts to rescue the inhibition by additional anti-E2 antibody produced equivocal results. In a few of the experiments, rescue was achieved, but the majority of attempts proved unsuccessful. One of the successful experiments is shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that anti-E2 antibody diluted 1:2,500 reversed the inhibition of replication by the E2 protein but higher dilutions did not. Finally, no stimulation of DNA replication (the third approach) was ever obtained upon addition of anti-E2 antibody to the assay system in comparison to the immune serum control (results not shown).

FIG. 6.

Membrane-associated DNA replication in vitro in the presence of different concentrations of the purified E2 protein. Membranes were extracted from B. subtilis by a modification of the technique of Marty-Mazars et al. (15) as described in Materials and Methods using low French pressure to minimize shearing of membrane-associated DNA. In vitro DNA synthesis was carried out as described previously (9). The control consisted of BSA prepared in the same buffer and the same concentration as the E2 protein.

FIG. 7.

Membrane-associated DNA replication in the presence of the purified E2 protein and various concentrations of anti-E2 antibody. Membranes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods by a modification of the method of Marty-Mazars et al. (15). In vitro DNA synthesis was carried out as described previously (9). The amount of E2 protein added was 12.5 μg/ml. Anti-E2 antibody and preimmune serum (preimm.) (used as a control) were added as shown.

DISCUSSION

The weight of evidence is positive for the identification of the PR protein as the E2 subunit of the PDH complex, despite the fact some of the antibody results and some of the gel retardation experiments were equivocal. The majority of the gel retardation analyses demonstrated not only that the R1-2 clone contained the E2 subunit in its entirety but that it was capable of binding B. subtilis origin region DNA and that sequences enriched in AT base pairs were involved. The lack of strict specificity could conceivably serve the role of the E2 subunit better as a repressor of DNA replication. The protein could function to prevent the binding of essential initiation proteins by binding to periodic AT-rich regions in the origin and could sterically hinder such proteins by altering the conformation of the DNA strand. As for why the purified E2 protein did not behave exactly like the E2 in the R1-2 extracts with respect to interaction with the AT-rich oligonucleotide, a variety of possibilities exist. The primary one may be that a conformation of the fusion E2 protein different from the E2 in the R1-2 cloned extract exists. In support of this possibility, studies with B. thuringiensis demonstrated that it was necessary to treat a His-tagged E2 with urea to retard the cry(b) DNA (22). Also, it is not known whether the lipoyl moiety of the E2 subunit is altered in any way after the His tag E2 purification. Nevertheless, the fact that the addition of purified His-tagged E2 protein to the membrane-associated DNA replication system inhibited such replication is a strong argument for its relationship to the PR protein.

The above-described possible difference in conformation between the purified His tag E2 protein and the E2 present in the R1-2 extracts may also explain why anti-E2 antibody did not behave exactly like anti-PR antibody in previous experiments (2, 11). If a different epitope were recognized immunologically, an antibody could be produced against the His-tagged E2 that was slightly different than that against the PR protein. They both recognize E2, as shown by the Western blots (Fig. 5), but they may behave differently in a complex in vitro membrane-associated DNA replication system. Yet the fact that repression of replication by E2 was rescued occasionally by the anti-E2 antibody (Fig. 7) does suggest that recognition occurs in the assay mix but that other complications exist (unknown at present).

How can the E2 protein exert its pleiotropic effects in regulation and in catabolism? One possibility is that the E2 subunit is made in excess over the amount required to complex stoichiometrically with the other components of the PDH complex to affect respiration (where it may not be subject to degradation by proteases) (2) because it has its own promoter (6). Under these conditions, the promoter of the E2 subunit would be activated to synthesize the additional amounts required for the other functions. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that the E2 subunit may interact with one or more additional proteins that are actually involved in regulating DNA replication in B. subtilis. Nevertheless, this protein constitutes a new and particularly direct link between the metabolic state of the cell and gene expression, in this case DNA replication. No such link has ever been demonstrated previously, although its relationship to other metabolic control processes in B. thuringiensis has been discussed above (22).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants to W.F. from the U.S. Army Research Office.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chodosh L A. Mobility shift DNA binding assay using gel electrophoresis. In: Ausabel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1988. pp. 12.2.1–12.2.7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eident-Wilkinson B, Mele L, Laffan J, Firshein W. Temporal expression of a membrane-associated protein putatively involved in repression of initiation of DNA replication in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:477–485. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.477-485.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firshein W. Role of the DNA/membrane complex in prokaryotic DNA replication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1989;43:89–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.43.100189.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firshein W, Kim P D. Plasmid replication and partition in Escherichia coli. Is the cell membrane the key? Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2061569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemila H, Palva A, Paulin L, Arvidson S, Palva I. Secretory S complex of Bacillus subtilis: sequence analysis and identity to pyruvate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5052–5063. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5052-5063.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacob F, Brenner S, Cuzin F. On the regulation of DNA replication of bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1963;28:329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laffan J J, Firshein W. DNA replication by a DNA/membrane complex extracted from Bacillus subtilis. Site of initiation in vitro and analysis of initiation potential of subcomplexes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2819–2827. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2819-2827.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laffan J J, Firshein W. Membrane protein binding to the origin region of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4135–4140. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4135-4140.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laffan J J, Firshein W. Origin-specific DNA-binding membrane associated protein may be involved in repression of initiation of DNA replication in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7452–7456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemon K P, Grossman A D. Location of bacterial DNA polymerase: evidence for a factory model of replication. Science. 1998;282:1516–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marty-Mazars D, Horiuchi S, Tai P C, Davis B D. Proteins of ribosome-bearing and free membrane domains in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1381–1388. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.3.1381-1388.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moriya S, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H. Structure and function of the region of the replication origin of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. III. Nucleotide sequence of some 10,000 base pairs in the origin region. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;13:2251–2265. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seiki M, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H. Structure of the region of the replication origin of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Nature (London) 1979;281:699–702. doi: 10.1038/281699a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seiki M, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H. Structure and function of the replication origin of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. I. Isolation and characterization of plasmids containing the origin region. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;183:220–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00270621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streyer L. Biochemistry. 3rd ed. 1988. Citric acid cycle. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex: an organized enzyme assembly, p. 379–382. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sueoka N. Cell membrane and chromosome replication in Bacillus subtilis. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;59:35–53. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suh J W, Boylan S A, Price C W. Gene for the alpha subunit of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase maps in the ribosomal gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:65–71. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.65-71.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter T, Aronson A. Specific binding of the E2 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase to the upstream region of Bacillus thuringiensis protoxin genes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7901–7906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]