With the world facing complex health challenges and limited resources, it’s critical that we maximize the impact of evidence to find effective solutions. Randomized control trials (RCTs) are widely used in health sciences to establish causal relationships between interventions (such as new medications) and outcomes (such as a reduction in a targeted disease condition like obesity). However, RCTs have limitations that constrain the impact of the evidence they generate (1, 2).

When used together, ABM and RCTs offer powerful synergy, each addressing key limitations of the other. Image credit: Shutterstock/Jelena Sebik.

Agent-based modeling (ABM) is a computational methodology for representing simulated dynamic pathways that connect exposures to outcomes (3–5) across diverse and interacting individuals and contexts [such as how retail density, price information, and individual characteristics work together to shape tobacco use patterns across very different cities (6)]. ABM can also consider potential intervention counterfactuals—that is, projected alternative states of the world representing results of untested interventions or adaptations of intervention components (3, 4). For example, ABM has been used during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand the potential impact of interventions being considered to contain spread of the virus (7, 8). Still, a lack of empiric data can limit the utility of ABM.

When used together, ABM and RCTs offer powerful synergy, each addressing key limitations of the other. We argue that more research should pair these two methods to increase significant research discoveries.

Addressing RCT Limitations

Three key limitations of RCTs that can hinder impact include 1) generalizability (external validity), 2) inability to assess mechanism of action, and 3) necessary assumptions regarding effects in groups (so-called “stable unit value treatment” and “average treatment effect” assumptions). For each of these, ABM offers the potential to complement RCTs to make evidence go further.

Cost, feasibility, or ethics can constrain the settings in which researchers can use RCTs and limit the diversity of sample, setting, and time horizon. In addition, the limited sample sizes for many RCTs create constraints on the number of variables that researchers can consider in drawing inferences due to statistical considerations. These limitations all pose a challenge to external validity—extrapolation of findings from an RCT to different populations, contexts, or timeframes. For example, a clinical trial can tell clinicians whether a drug is effective within the sample, but it cannot show how it would work for other populations of people who weren’t represented in the trial or across longer time periods or different settings than were studied.

ABM can help address this concern by providing a principled way to translate evidence from one setting (the site of the original RCT) to another (a novel counterfactual), leveraging the method’s ability to represent dynamic pathways while adjusting for heterogeneity between contexts (3, 7, 9). Even after RCTs are implemented with the highest quality, external validity of the resulting evidence suffers if features of the environment or population being studied change during or after study completion. ABM offers a valuable complement to approaches such as the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomization Trial (SMART), an adaptive design used to address some of these limitations (10, 11). SMART allows for limited within-person and between-person heterogeneity in an RCT context by developing a priori tailoring variables that can change over time (allowing researchers to adapt the trial with a predetermined approach). For example, in a SMART trial testing an obesity intervention, a predetermined approach could be taken if body mass index (BMI) isn’t responsive to the intervention. Unfortunately, this will always be bounded by a finite set of variable changes. In contrast, ABM allows for hundreds of thousands of in silico variable changes or combinations (7).

A second limitation for RCT evidence arises because RCTs tell us what causal relationships exist between things directly measured, but not necessarily why these relationships exist. This not only makes translation across settings difficult, but also restricts insight into alternative conditions, such as doses or combinations of intervention elements beyond those studied. Many RCTs fail to show an effect but cannot conclude that the overall intervention approach was truly ineffective without exploring variations around intervention implementation or potential differential attrition (12). For example, in a study of 600 parent–preschool child pairs aimed at reducing emergence of early childhood obesity, researchers documented an early intervention effect; however, this disappeared by the three-year study endpoint when examining the whole sample (13). Yet for a subset of intervention participants, BMI improved. The RCT does not explain why the intervention worked for some and not others, nor how modifications of the intervention design might have helped it work more consistently across and within participants. ABM can help overcome these limitations, providing a powerful tool to develop and test hypotheses about why relationships between exposures and outcomes are (or are not) observed (3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 14–17), drawing in both auxiliary data (such as from other available datasets) and theory. Although this approach is not without challenges (9), carefully building confidence in a mechanistic model of key processes can allow evaluation in silico of intervention formulations, settings, or loss-to-follow-up scenarios that have not yet been assessed in vitro or in vivo (10, 16–18).

A third limitation of RCT evidence arises from fundamental assumptions necessary for causal inference using this tool. The stable unit value treatment assumption in RCTs means that receipt of treatment by one individual is assumed to not affect the impact of treatment or nontreatment on someone else (effectively ignoring any potential social influence or contagion). For some important problems in health, this inability to consider social influence can sharply limit insight. The randomization necessary for the RCT approach worsens this limitation by removing individuals out of naturally occurring social contexts (1). ABM can assist with reintroducing social effects into the analysis because it is particularly well suited for studying interactions among individuals—for example, the social spread of disease, information, or behavior (7, 8).

Another common set of RCT assumptions, related to estimating an average treatment effect, generally require that participants have a predictable and stable outcome from the intervention. If interventions have differing effects across individuals (due to heterogeneity in biology, behavior, or context) or differing effects within an individual across time (due to adaptation), this average effect estimate may not yield clear insights. Here, ABM can complement RCTs by accounting for adaptability and heterogeneity in treatment response, as well as potential interaction between intervention elements—for example, synergy between different intervention actions that work together more powerfully than they can individually to reduce smoking or obesity (4, 6, 8, 15, 19).

Addressing ABM Limitations

ABM, in turn, can strongly benefit from partnership with RCTs to overcome important limitations of its own. Although ABM has seen rapid uptake along with other complex systems science tools across the health sciences (6, 8, 15–26), data availability often constrains potential applications. This is because an important strategy for testing and improving ABM is to compare output from the computational simulation to real-world empiric data taken from observational or experimental sources. Use of ABM to extrapolate across contexts requires a solid representation of the mechanistic structure of a system. Where such structure is not already well understood, ABM can be used to build theory by identifying hypothesized structures and testing them using existing evidence (6, 7, 14, 15, 24, 25). Resultant models can be used with suitable caution to simulate potential real-world intervention effects (7, 16, 17). While such testing cannot prove definitively that a particular mechanistic representation is correct, identifying models that are consistent with data from both experimental and observational sources generates insights to inform promising interventions for future trials (27, 28).

RCT data are a particularly well-suited partner for developing and testing ABMs for several reasons. First, simulated data from an ABM can be disaggregated at the level of the individual and can extend across long time periods with high granularity. ABM data can also include multiple individual and contextual factors, establishing within the simulated world the specific role of each factor influencing each outcome. For example, ABM could be applied to behaviors associated with improved health, such as physical activity, to understand what drives differences between individuals and across time, as well as how and why these drivers might change over time. Empirical datasets that share more of these features (e.g., repeated observations of individuals across many contexts with strong inferred relationships to outcomes, such as RCTs) allow for the best and most rigorous tests of ABM, including more nuanced insights and better adjudication between competing mechanistic hypotheses. Thus, an RCT with standardized observation of physical activity at the daily level across many individuals and time points would provide an ideal partner to test ABM of physical activity’s determinants. The strategy of testing predictive models (such as ABMs) with experiments (such as RCTs) is a cornerstone approach across many other fields of science, especially the natural sciences (27).

Today, it remains rare to see work pairing these two methods in the health sciences. However, two recent case studies are illustrative of the potential (18, 20, 29). In the first example (18, 29), empiric data from an information technology randomized control intervention (29) were used to build an agent-based model assessing varying conditions for intervention delivery. The intervention, CommunityRx, was a clinic-based approach to provide patients with an individualized list of community resources. The agent-based model allowed the authors to examine community referral information diffusion by conducting a series of in silico experiments. First, the existing intervention was replicated in silico, and, second, additional testing was conducted, altering who delivered the intervention (physicians, nurses, or clinical clerks). Together, this generated new information to guide further dissemination in different environments than were tested in the original RCT (18).

The strongest potential synergy from combining these two methods may come through more iterative and integrated blending of the tools.

The second example (20) demonstrates how ABM can extrapolate from existing empiric evidence to novel contexts to make predictions regarding interventions that are later validated in subsequent RCTs. In a study of inflammatory response after trauma, empiric data from a cohort of blunt trauma patients examined injury severity score (ISS), length of stay (LOS), and inflammatory markers. Using these data, a virtual patient-specific trauma agent-based model was developed, along with a larger population virtual cohort. The model predicted LOS, multiple organ dysfunction, and ISS. Findings were then validated in a cohort of trauma patients. This seamless partnership between empiric data and in silico virtual cohorts allowed the investigators to test more targeted hypotheses. This example illustrates successful combination of a more reductionist clinical trial design with mechanistic modeling. Doing so enabled researchers to examine the sort of interactions and adaptations that are often seen in complex biological circumstances, such as trauma.

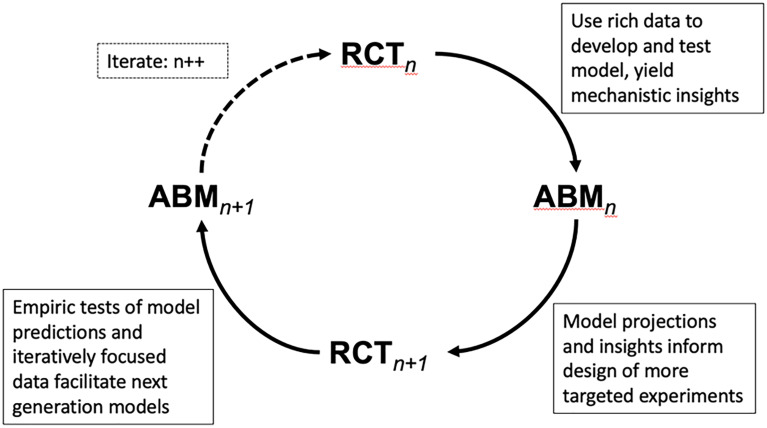

For all the reasons above, more work combining RCTs and ABM would benefit health science. The strongest potential synergy from combining these two methods may come through more iterative and integrated blending of the tools (Fig. 1). In such an approach, an always-improving combination of real and simulated data could be used to iteratively improve our understanding and treatment of complex diseases (for which both causes and outcomes may vary considerably across individuals). Doing so would help make evidence and scarce resources go much further in a complex world.

Fig. 1.

Powerful insight could come from a cycle of models and experiments in which agent-based models leverage existing RCTs and other data to develop and test mechanistic and predictive insights. These models then, in turn, allow design of more precise and targeted new RCT experiments that feed back to inform an improved generation of models. This deliberate sequence of models and inferences is not yet common in population health, but is especially well suited for advancing progress on complex challenges replete in the field. The cycle is shown in discrete steps, but could also grow to include real-time adaptive adjustment in both trials and models, with each informing the other.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Author contributions: R.A.H. and S.B. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this work are those of the authors and have not been endorsed by the National Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1.Deaton A., Cartwright N., Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med. 210, 2–21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Concato J., Shah N., Horwitz R., Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1887–1892 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall B. D. L., Galea S., Formalizing the role of agent-based modeling in causal inference and epidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 181, 92–99 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond R. A., “Considerations and best practices in agent-based modeling to inform policy” in Assessment of Agent-Based Models to Inform Tobacco Policy (National Academies Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luke D. A., Stamatakis K. A., Systems science methods in public health. Ann. Rev. Pub. Health 33, 357–376 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond R. A., et al. , Development of a computational modeling laboratory for examining tobacco control policies: Tobacco Town. Health & Place 61, 102256 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedson J., et al. , A review and agenda for integrated disease models including social and behavioral factors. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 834–846 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Gara D., et al. , TRACE-Omicron: Policy counterfactuals to inform mitigation of COVID-19 spread in the United States. Adv. Theory Simul. 6, 2300147 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan A. L., et al. , Disseminated effects in agent based models: A potential outcomes framework to inform pre-exposure prophylaxis coverage levels for HIV prevention. Am. J. Epidemiol. 190, 939–948 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins L. M., Murphy S. A., Strecher V., The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 32 (5 Suppl), S112–S118 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almirall D., Nahum-Shani I., Sherwood N. E., Murphy S. A., Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: With application to weight loss research. Transl. Behav. Med. 4, 260–274 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Templeton A. J., Amir E., Tannock I. F., Informative censoring—a neglected cause of bias in oncology trials. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 327–328 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barkin S. L., et al. , Effect of a behavioral intervention for underserved preschool-age children on change in body mass index: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320, 450–460 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall K., Hammond R. A., Rahmandad H., Dynamic interplay between homeostatic, hedonic, and cognitive feedback circuits regulating body weight. Am. J. Public Health 104, 1169–1175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasman M., et al. , An agent-based model of child sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: Implications for policies and practices. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 116, 1019–1029 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasman M., et al. , Childhood sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: An agent-based model of context-specific reduction efforts. Am. J. Prev. Med. 65, 1003–1014 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Combs T. B., et al. , Modeling the impact of menthol sales restrictions and retailer density reduction policies: Insights from Tobacco Town Minnesota. Tobacco Control 29, 502509 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau S. T., et al. , Building and experimenting with an agent-based model to study the population-level impact of CommunityRx, a clinic-based community resource referral intervention. PloS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009471 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation (National Academies Press, 2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown D., et al. , Trauma in silico: Individual-specific mathematical models and virtual clinical populations. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 285ra61 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond R. A., Osgood N., Wolfson M., “Using complex systems simulation modeling to understand health Inequality” in Growing Inequality: Bridging Complex Systems, Population Health, and Health Disparities, Kaplan G. A., Galea S., Eds. (Westphalia Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson K. H., Hammond R. A., Homer J. B., Complex adaptive systems modeling to address cardiovascular disparities: Complex science for a complex problem. Circulation 148, 201–203 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutuskey L., et al. , “Applicability of systems science approaches to the dietary guidelines for Americans” (Tech. Rep., US Department of Agriculture, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walpole J., Papin J. A., Peirce S. M., Multiscale computational models of complex biological systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 15, 137–154 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiatt R. A., et al. , A complex systems model of breast cancer etiology: The Paradigm II Model. PLOS One 18, e0282878 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne-Sturges D. C., et al. , Defining and intervening on cumulative environmental neurodevelopmental risks: Introducing a complex systems approach. Environ. Health Perspect. 129, 35001 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearl J., Causality (Cambridge University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldrick R. C., Randomized trials vs real-world evidence: How can both inform decision-making? JAMA 329, 1352–1353 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindau S. T., et al. , CommunityRx: A real world controlled clinical trial of a scalable, low-intensity community resource referral intervention. Am. J. Public Health 109, 600–606 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]