Abstract

Pink disease of pineapple, caused by Pantoea citrea, is characterized by a dark coloration on fruit slices after autoclaving. This coloration is initiated by the oxidation of glucose to gluconate, which is followed by further oxidation of gluconate to as yet unknown chromogenic compounds. To elucidate the biochemical pathway leading to pink disease, we generated six coloration-defective mutants of P. citrea that were still able to oxidize glucose into gluconate. Three mutants were found to be affected in genes involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes, which are known for their role as specific electron acceptors linked to dehydrogenase activities. Three additional mutants were affected in different genes within an operon that probably encodes a 2-ketogluconate dehydrogenase protein. These six mutants were found to be unable to oxidize gluconate or 2-ketogluconate, resulting in an inability to produce the compound 2,5-diketogluconate (2,5-DKG). Thus, the production of 2,5-DKG by P. citrea appears to be responsible for the dark color characteristic of the pink disease of pineapple.

Pink disease of pineapple is characterized by the production of distinct dark orange-brown color produced in the fruit tissue after the heating process of canning (27). Since the fruits remain superficially symptomless in the field, eliminating the disease by culling fruits either in the field or at postharvest is highly problematic and therefore of economic importance. Pink disease was first observed in Hawaii and was later found in Australia and in the Philippines (22, 24, 27). The incidence of seasonal factors, such as rainfall and temperature, were analyzed to reveal that flowering during wet weather preceded by dry periods increases pink disease occurrence (18). Confusion on the cause of pink disease remained for many years because four different bacteria were thought to be responsible for the disease: Erwinia herbicola, Gluconobacter oxydans, Enterobacter agglomerans, and Acetobacter aceti (28). However, recent molecular studies of the disease has identified Pantoea citrea as the causal agent of pink disease (8).

P. citrea, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family commonly isolated from fruit and soil samples, was shown to effectively produce 2,5-diketo-d-gluconic acid from d-gluconic acid and 2-keto-d-gluconic acid (20, 37). To identify the bacterial genes involved in formation of the chromogenic compound(s) characteristic of pink disease, we used the virulent strain 1056R and developed an assay that enabled us to reproduce the disease under laboratory conditions (7). We then generated and analyzed various chemically induced mutants of P. citrea that were unable to induce pink disease. This allowed us to show that one of the key steps leading to the coloration of pineapple juice was the oxidation of glucose to gluconate (7). In P. citrea, this process is carried out by two highly similar, membrane-bound quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenases, GdhA and GdhB (7, 26). gdhA is constitutively expressed at very low levels, while gdhB is fully expressed to produce gluconate from glucose (26). Mutants affected in the ability to oxidize glucose were able to carry out coloration of pineapple when supplemented with gluconate in the growth medium, indicating that production of gluconate is the first step in the pathway leading to the formation of the chromogenic compound(s) (7, 26).

To further characterize additional steps involved in color formation, we used transpositional mutagenesis to generate mutant strains of P. citrea that, although still able to oxidize glucose to gluconate, are unable to color pineapple juice. Six independent mutants were isolated. Their biochemical and genetic characterization revealed that the genes implicated in pink disease are involved in the conversion of gluconate to 2-keto-d-gluconate (2-KDG) and 2,5-diketo gluconate (2,5-DKG). We also identified several open reading frames (ORFs) for genes required for the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes that are used as electron acceptors in the oxidation reactions in P. citrea. Taken together, our data show that accumulation of 2,5-DKG is directly responsible for the intense coloration characteristic of pink disease of pineapple.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, growth conditions, and antibiotics.

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium (29). P. citrea strains were grown at 30°C either in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing rifampin, in mannitol-glutamate-yeast (MGY) medium (8), or in pineapple juice (8). All media were solidified with 1.5% (wt/vol) Bacto Agar (Difco Laboratories). E. coli and P. citrea competent cells were transformed by electroporation as previously described (7). After transformation with pBluescript SKII(−) [pBSSKII(−)] derivatives, E. coli transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal; 40 μg/ml; Denville), and 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Gibco-BRL Life Technologies). Antibiotics (Sigma) were used at the following concentrations (micrograms per milliliter): rifampin, 100; kanamycin, 15; tetracycline, 10 and 15 for P. citrea and E. coli, respectively; and ampicillin, 250 and 100 for P. citrea and E. coli, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | hsdR17 (r−K m+K) Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 φ80dlacZΔM15 supE44 thi-1 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 relA1 | 29 |

| S17-1λpir | thi pro (r− m+) recA RP4 2-Tc::Mu Km::Tn7 λ pir Smr Tpr | 35 |

| Pantoea citrea | ||

| 1056R | Wild type, pink+; Rifr | 8 |

| 1058RC | gdhA::cat; Rifr Cmr | 26 |

| CP6C8 | Pink− derivative of 1056R; Rifr Tcr | This work |

| CP9D9 | Pink− derivative of 1056R; Rifr Tcr | This work |

| CP9G10 | Pink− derivative of 1056R; Rifr Tcr | This work |

| CP15E7 | Pink− derivative of 1056R; Rifr Tcr | This work |

| 103C11 | Pink− derivative of 1058RC; Rifr Cmr Tcr | This work |

| 105D2 | Pink− derivative of 1058RC; Rifr Cmr Tcr | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK II | ColE1 origin; Apr | Stratagene |

| pUCKm | pUC18 derivative; Apr Kmr | F. Chédin, unpublished data |

| pBR322 | Tcr Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pBSL346 | Mini-Tn10 derivative; Tcr | 1 |

| pEC2 | ccm operon of E. coli into pUCBM20; Apr | 41 |

| pUCD5066 | 4-kb PvuII fragment from CP6C8 cloned into EcoRV of pBSSKII(−); Tcr Apr | This work |

| pUCD5070a | 3–3.3-kb NsiI fragment from CP9D9 cloned into PstI of pUCKm; Tcr Apr Kmr | This work |

| pUCD5070b | 3–3.3-kb NsiI fragment from CP9G10 cloned into PstI of pUCKm; Tcr Apr Kmr | This work |

| pUCD5071 | 6-kb PvuII fragment from 105D2 cloned into EcoRV of pBSSKII(−); Tcr Apr | This work |

| pUCD5074 | 2.8-kb AvaI fragment from 103C11 cloned into XmaI of pUCKm; Tcr Apr Kmr | This work |

| pUCD5077 | dsbD (1930 bp) from 1056R cloned into pBSSKII(−); Apr | This work |

| pUCD5079 | 9–10-kb PvuII fragment from CP15E7 cloned into EcoRV of pBSSKII(−); Tcr Apr | This work |

| pUCD5089 | orfB (2,169 bp) from 1056R cloned into pBSSKII(−); Apr | This work |

| pUCD5094 | ccmC (896 bp) from 1056R cloned into pBSSKII(−); Apr | This work |

| pUCD6718 | 9-kb EcoRI fragment from CP9G10 cloned into EcoRI of pBSSKII(−); Tcr Apr | This work |

Pink test and coloration assay.

The Pink test was performed in pineapple juice as previously described (7). For the coloration assay, bacteria were grown in MGY supplemented with various carbon sources (see below) for 3 days at 30°C with gentle shaking (150 rpm). The culture was then autoclaved for 5 min at 121°C, and the cells were removed by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 5 min). The absorbance of the supernatant was determined spectrophotometrically at 420 nm in a Shimadzu spectrophotometer.

Carbon sources.

The carbon sources d-arabinose, d-cellobiose, fructose, d-fucose, d-galactose, d-lactose, maltose, d-melibiose, raffinose, l-rhamnose, d-ribose, saccharose, d-trehalose, and d-xylose were used at 100 mM. d-Gluconic acid, d-glucose, 2-keto-D-gluconic acid, 5-keto-d-gluconic acid, 2,5-DKG, and gulonic acid were used at 50 mM.

Plasmids and DNA manipulations.

Cloning vectors and plasmids used and constructed in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid screening was carried out by the alkaline lysis method of Birnboim (4). Large-scale plasmid DNAs were prepared using a Qiagen plasmid kit. Total DNA extraction was performed by the method of te Riele et al. (39). DNAs were cleaved with restriction endonucleases as specified by the suppliers (Boehringer Mannheim and New England Biolabs). Ligations were performed with T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim) according to standard protocols (29).

Transposition mutagenesis.

Tn10 insertion mutants were isolated by using the Tn10 derivative pBSL346 (1). pBSL346 was introduced into P. citrea 1056R and 1058RC by electroporation; the mutants generated were selected on solid LB medium supplemented with rifampin (100 μg/ml) and tetracycline (15 μg/ml) and tested for the ability to color pineapple juice. Total DNA from a 5-ml overnight culture of the putative mutants was purified, digested with convenient restriction enzymes, analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham). The bound DNA was then hybridized with an α-32P-labeled probe corresponding to the 1.3-kb EcoRI-StyI fragment containing the tet gene from plasmid pBR322 to detect transposon Tn10. Fragments with sizes ranging from 3 to 9 kb were then purified from agarose gel with a Wizard purification kit (Promega), ligated into convenient unique sites of pBSSKII(−) or pUCKm vector, and transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells with selection for tetracycline resistance (Tcr). Among the Tcr transformants, those containing plasmids of the expected size (vector plus insert) were selected for nucleotide sequencing.

In mutants CP9D9 and CP9G10, the Tn10 derivative was localized on two 3.3-kb NsiI chromosomal fragments, which were cloned into the unique PstI site of pUCKm, yielding plasmids pUCD5070a and pUCD5070b, respectively. In mutant 105D2, the transposon was localized on a 6-kb PvuII chromosomal fragment (see Fig. 3A), which was further cloned into the unique EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), leading to plasmid pUCD5071. To extend the size of the region, a 9-kb EcoRI DNA fragment containing the transposon was isolated from CP9G10 and was cloned into the EcoRI site of pBSSKII(−), yielding plasmid pUCD6718. The sequence of a 4,349-bp DNA contig was then determined and analyzed.

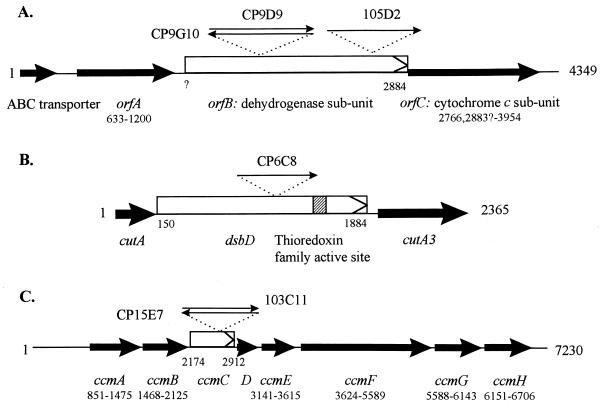

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the genes inactivated by transposition mutagenesis. Thin arrows represent the Tn10 insertion with the name of the mutant. Genes inactivated are designated by arrowed boxes; other genes are marked by dark arrows. Coordinates of genes are indicated. (A) Mutant CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2. Tn10 is inserted at nt 1858 (in opposite orientation in CP9D9 and CP9G10) and 2703, respectively. The sequence of the ABC transporter gene is only partial. (B) Mutant CP6C8. Tn10 is inserted at nt 1186. (C) Mutants CP15E7 and 103C11. Tn10 is inserted, in opposite orientation, at nt 2595 and 2604, respectively.

In mutant CP6C8, the Tcr marker of transposon Tn10 was localized on a 4-kb PvuII chromosomal fragment. This fragment was cloned into the unique EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), leading to plasmid pUCD5066.

In mutant 103C11, the Tn10 Tcr marker was localized on a 2.8-kb AvaI chromosomal fragment, which was cloned into the unique XmaI site of pUCKm, leading to plasmid pUCD5074. In mutant CP15E7, the marker was localized on a 10- to 12-kb PvuII chromosomal fragment which, upon cloning into the EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), led to plasmid pUCD5079. Nucleotide sequences of pUCD5074 and pUCD5079 revealed that the 2.8-kb AvaI DNA fragment and the larger PvuII DNA fragment were overlapping.

DNA hybridization, sequencing, and PCRs.

Southern blot hybridizations were performed as previously described (29) and were carried out at 65°C with Rapid-Hyb buffer according to the directions of the supplier (Amersham Life Science). Probes were prepared by nick translation (Boehringer Mannheim) using [α-32P]dCTP as the radioactive nucleotide (Dupont-NEN Products). Double-stranded DNA sequences were determined by the dideoxy-chain termination method (30) using a Sequenase version 2.0 kit (USB Amersham) with the M13 universal primers or convenient primers (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies) and [α-35S]dATP as the radioactive nucleotide (DuPont-NEN Products). The sequences were run on a GenomyxLR sequencer (Genomyx Co.). Sequences were compiled and comparative analyses were made with the Wisconsin Package version 9.0 (Genetics Computer Group, University of Wisconsin, Madison) and the BlastN and BlastX programs developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. All PCRs were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 apparatus (Perkin-Elmer), using the recombinant Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and convenient primers (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies). Nucleotide sequences of the constructs were verified to ensure that the inability to complement the mutant was not due to mutations introduced during the PCRs. A 2,169-bp fragment containing the orfB gene was amplified using primers 5070-11 (5′-AACGGGACAATCAGTTCAGC-3′ nucleotides [nt] 889 to 908) and 5071-R1 (5′-AACGCTGTCTTACTGCCG-3′; nt 3058 to 3041) along with total DNA from strain 1056R as the template. The amplified fragments were then cloned into the EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), yielding plasmid pUCD5089. A 3,848-bp DNA fragment containing orfA, orfB, and orfC was amplified using primers StartEcoRI (5′-AGCAGAATTCGCGCGTTGTAACACTCCACCGC-3′; nt 483 to 512) and EndBamHI (5′-TCTGGTGGATCCTTCAGAGTTCAGTGATGTTAAGC-3′; nt 4331 to 4298) (the underlined nucleotides represent restriction sites for EcoRI and BamHI, respectively). After digestion of the PCR product with the EcoRI and BamHI, the fragment was cloned into pBSSKII(−), previously digested with the same enzymes.

The dsbD gene was amplified using primers 5066PCR1 (5′-GTAGTATCTGCTCATGTAC-3′; nt 1971 to 1953) and 5066PCR2 (5′-ATACGGAGCATCAACAGGAC-3′; nt 41 to 60) along with total DNA from wild-type strain 1056R as a template. The resulting 1,930-bp fragment was cloned into the EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), yielding plasmid pUCD5077.

The ccmC gene was amplified using total DNA from strain 1056R as the template and primers hem1 (5′-TGGCACCTTTTGCCACAGCCGCAGCGG-3′; nt 2081 to 2107) and hem2 (5′-GCCAGACATAGAAGGCATAACCTCCC-3′; nt 2977 to 2952). The resulting 896-bp fragment was cloned into the EcoRV site of pBSSKII(−), to yield plasmid pUCD5094.

Dehydrogenase assays.

In vivo glucose dehydrogenase activity was detected on solid MGY supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) glucose and eosin yellow-methylene blue as previously described (26).

Detection of gluconate dehydrogenase activity was adapted from the method of Bouvet et al. (5). Bacteria were grown overnight in 5 ml of MGY supplemented with 50 mM d-gluconic acid and then collected by centrifugation (2,700 × g for 3 min). The pellet was rinsed once with fresh sterile MGY and resuspended in 50 μl of sterile water. Then 10-μl aliquots of bacterial suspensions were dispensed into the wells of a microtiter plate, each well containing 100 μl of solution A (0.2 M acetate buffer [pH 5.2], 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 2.5 mM MgSO4, 50 mM gluconate, 1 mM iodoacetate). The microtiter plate was incubated at 30°C for 20 min with gentle shaking (100 rpm). Then 10 μl of 0.1 M potassium ferricyanide was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 30°C for 40 min with shaking (100 rpm). Finally, 50 μl of solution B [0.6 g of Fe2(SO4)3, 0.36 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate, 11.4 ml of 85% phosphoric acid, distilled water to 100 ml) was added to the wells. Wells were examined for the development of a green to blue color within 15 min at room temperature. The color of the negative control (MGY medium without bacteria) remained yellow.

The 2-ketogluconate dehydrogenase assay was the same as described above, except that the cells were grown in MGY supplemented with 50 mM 2-keto-d-gluconate and solution A contained 50 mM 2-keto-d-gluconate instead of d-gluconate.

TLC.

Qualitative detection of d-gluconate (D-Gln), 2-KDG, and 2,5-DKG was done by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) according to Joveva et al. (19). The three acids were separated on Silica Gel 60 plates (20 by 20 cm; Whatman) impregnated with 5% metaphosphoric acid, using a two-step migration. The first migration was done in solvent A (isopropanol-pyridine-water-acetic acid [8:8:1:4]) until the front of the solvent was 12 cm away from the start. The plate was then air dried, and the second migration took place in solvent B (isopropanol-pyridine-water-acetic acid [8:8:3:4]) until the front of the solvent was 18 cm away from the start. The plate was then air dried before spraying freshly prepared reactive C (p-anisaldehyde 0.5% [Sigma] in methanol-sulfuric acid-acetic acid [9:5:5]). Finally the plate was dried under vacuum at 120°C for 10 to 15 min. The retention front (Rf) values corresponding to d-glucose, d-Gln, 2-KDG, and 2,5-DKG are 0.56, 0.36, 0.36, and 0.28, respectively. Despite the fact that d-Gln and 2-KDG show the same Rf, the two compounds are easily distinguishable since d-Gln gives a light blue spot, while the spot corresponding to 2-KDG is dark brown.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence of the dsbD gene, the ccm operon, and the putative 2-ketogluconate dehydrogenase operon are deposited in GenBank with accession no. AF102175, AF103874, and AF131202, respectively.

RESULTS

Glucose catabolism is responsible for development of pink disease.

We previously showed that the oxidation of d-glucose to d-Gln is the first step leading to pink disease of pineapple (7, 26). Since glucose dehydrogenases can oxidize glucose and other aldoses to their corresponding acids (9, 17), we wanted to determine more precisely which sugars can be used as substrates to produce the coloration of pineapple juice by P. citrea. For that purpose, P. citrea 1056R was grown for 3 days in MGY medium containing 100 mM carbon source (as described in Materials and Methods). The cultures were autoclaved, and the relative (before and after bacterial growth) turbidity (optical density [OD]) of the supernatant was measured at 420 nm. A substantial increase of the OD is observed when glucose is present in the medium, indicating that glucose is the key substrate leading to the dark coloration of pineapple juice.

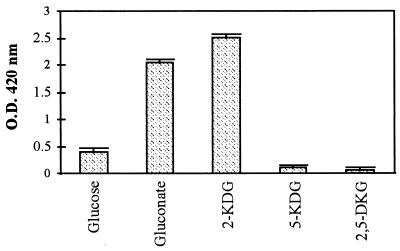

In bacteria which possess a direct glucose oxidation metabolism, d-glucose is oxidized to d-Gln, which can be further oxidized into 2-KDG or 5-KDG by membrane-bound gluconate dehydrogenases 55). Furthermore, a number of Acetobacter, Erwinia, and Gluconobacter species are able to oxidize 2-KDG to 2,5-DKG by membrane bound 2-ketogluconate dehydrogenases (5, 43). We therefore decided to test these different compounds for the ability to be used as a substrate for the dark coloration characteristic of pink disease. We supplemented liquid MGY medium with 50 mM d-glucose, d-Gln, 2-KDG, 5-KDG, or 2,5-DKG and measured the relative absorbance of the clarified medium supernatant after 3 days of growth, as described above. As shown in Fig. 1, coloration of the medium was observed with three of the sugars, with the most intense coloration obtained with 2-KDG. Interestingly, addition of 5-KDG or 2,5-DKG to the medium appears to have no effect on the absorbance after growth (Fig. 1). In the case of 2,5-DKG, this is because when put into solution, this sugar already forms the dark orange color characteristic of pink disease (data not shown). Therefore, although no increase in the intensity of the color was observed after growth of P. citrea, the results suggest that pink disease is due to the accumulation of 2,5-DKG.

FIG. 1.

Involvement of sugars in pink disease color. P. citrea 1056R cells were grown for 3 days in MGY supplemented with 50 mM sugar substrates from the Entner-Doudoroff pathway as described in Materials and Methods. The growth medium was then autoclaved for 5 min at 121°C, cells were removed by centrifugation, and the relative OD (inoculated medium versus noninoculated medium treated under the same conditions) was measured at 420 nm. Each bar corresponds to the mean of three independent measurements with standard deviation.

Isolation of color-deficient mutants.

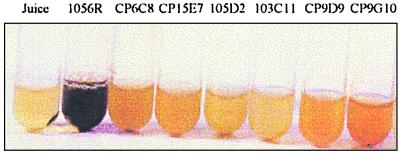

We recently characterized color-deficient mutants of P. citrea that are affected in the ability to oxidize glucose to gluconate, allowing the identification of the first step of the pathway leading to pink disease (7, 26). To identify additional genes involved in the disease, and to confirm our physiological studies using various derivatives of d-glucose, we used Tn10 transposon mutagenesis to generate mutant strains of P. citrea that are unable to color pineapple juice but can still carry out the first oxidation step. Plasmid pBSL346 (1) containing transposon Tn10 was introduced into P. citrea 1056R as described in Materials and Methods. Of the 2,578 independent Tcr mutants obtained, 8 were unable to color pineapple juice; of these 8, 6 were still able to oxidize glucose into gluconate. The phenotypes of these six mutants (CP6C8, 103C11, CP15E7, CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2) regarding the ability to color pineapple juice are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. The genes affected in these mutants were cloned and sequenced, and their functions were analyzed as described below (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Phenotypes of various P. citrea mutants unable to induce pink disease of pineapple. Strains were grown for 3 days in pineapple juice at 30°C and then autoclaved for 5 min at 121°C. The P. citrea wild-type strain (1056R) was able to color pineapple juice, while mutants CP6C8, CP15E7, 105D2, 103C11, CP9D9, and CP9G10 were not . Pineapple juice medium that was not inoculated with bacteria remained yellow.

TABLE 2.

Color-forming activity of P. citrea mutants

| Strain | Color-forming activity (%)a |

|---|---|

| 1056R | 100 |

| CP6C8 | 5.8 ± 2.0 |

| 103C11 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| CP15E7 | 2.4 ± 0.4 |

| CP9D9 | 24.3 ± 0.7 |

| CP9G10 | 38.3 ± 2.4 |

| 105D2 | 17.4 ± 2.8 |

Measured at 420 nm after 3 days of growth in pineapple juice. Each value corresponds to the mean of six measurements ± standard deviation.

Identification of a three-gene operon encoding a dehydrogenase complex involved in pink disease formation.

Sequencing of the CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2 insertion sites revealed that the transposon was inserted at the same locus, orfB, in all three cases (Fig. 3A). Further sequencing of the region flanking this locus indicates that it contains two additional genes, orfA, and orfC (GenBank accession no. AF131202). orfA, orfB, and orfC are likely to be organized as an operon, since no transcription termination signal could be detected between them. Intriguingly, no obvious expression signals (−35 and −10 boxes, ribosome-binding sequence) were detected upstream of the operon. However, upstream of orfA in the contig is a partial ORF (nt 1 to 443) showing 62% similarity at the amino acid level with a hypothetical ABC transporter ATP-binding protein of Methanococcus jannaschii (6) (data not shown) (Fig. 3A). This partial ORF is followed by a potential rho-independent transcriptional terminator 79 bp downstream of the stop codon (nt 524 to 537), indicating that it belongs to a separate transcriptional unit.

The first gene of the operon, orfA (nt 633 to 1200), can encode a novel protein of 189 amino acid residues. It is followed by a second putative gene, orfB, with no obvious transcription terminator being located between the two elements. The putative gene product encoded by orfB shares 34% similarity with a gluconate dehydrogenase subunit precursor from Erwinia cypripedii (data not shown) (43). Four potential start codons (ATG) for orfB are located at positions 1225, 1228, 1231, and 1408 (Fig. 3). Depending on which of these initiating codons is used, the OrfB protein would be 553, 552, 551, and 492 amino acids (aa), respectively. Following orfB is a third putative gene, orfC. Two possible start codons are detected for orfC: nt 2766 (in which case orfC would overlap orfB by 120 nt) and nt 2883. The second possible start codon of orfC is more likely to be used since it is preceded by a reasonable ribosome-binding site (nt 2871 to 2876). Depending on the start codon used, orfC would encode for a protein of 396 or 357 aa. This putative OrfC protein is 60% similar to the alcohol dehydrogenase cytochrome c subunit of A. polyoxogenes (38) and the cytochrome c precursor of the membrane-bound gluconate dehydrogenase from E. cypripedii (43). Three cytochrome c family heme-binding sites were found at nt 3018 to 3032 (CQACH), 3462 to 3476 (CDTCH) and 3888 to 3902 (CASCH). It therefore appears that this operon encodes for a dehydrogenase complex composed of three subunits: a flavoprotein dehydrogenase (OrfB), its association cytocchrome c subunit (OrfC) and a third possible subunit of unknown function (OrfA).

The three transposon insertions affecting orfB are located at positions 1858 and 2703. In mutants CP9D9 and CP9G10, Tn10 is inserted in opposite orientation at position 1858 (Fig. 3A). Thus, orfB appears to be essential for color formation. Note that we cannot rule out potential contribution by orfC which was also likely affected in the three mutants, due to polar effects of the insertion.

To verify that the deficiency of mutants CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2 is due to the inactivation of orfB, we constructed pUCD5089 and pUCD5092 containing the full-length orfB gene cloned in both orientations with respect to the lacZ promoter of pBSSKII(−). We introduced these plasmids into strains CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2 and tested four independent transformants in complementation assays. Results indicated that none of the transformants restored the ability of the strain to induce the coloration of pineapple juice (data not shown). This result could simply indicate that orfB was not expressed in our construct, or that the defect in the three mutant strains is due to a polar effect of the transposon insertion on orfC. To test these hypotheses, we cloned orfC alone, as well as a fragment containing both orfB and orfC or orfB and orfA (data not shown). However, none of these constructs could complement the mutants, strongly suggesting that the three genes are necessary for complementation. We could rule out a polar effect on an ORF downstream of orfC since no significant ORF (longer than 60 aa) could be detected downstream of orfC (data not shown). We then amplified a 3,848-bp DNA fragment containing the three ORFs, as described in Materials and Methods, and added the ligation mixture to E. coli DH5α competent cells. However, none of the transformants contained an insert of the correct size: all of the plasmids recovered after transformation carried deletions, suggesting that the operon might encode a product that is toxic to E. coli. Our attempts to clone the operon directly in P. citrea CP9D9 or in a lower-copy-number vector (such as pACYC184) were also unsuccessful (the plasmids recovered after transformation also carried deletions), again suggesting a toxic effect results when the entire operon is expressed.

Biogenesis of c-type cytrochrome is required for pink disease formation.

Isolation and sequencing of the CP6C8 insertion site demonstrated that the Tn10 was inserted in 1,734-bp ORF that would encode a 578-aa protein (nt 150 to 1884) (Fig. 3B). Homology searches revealed that this putative protein is 80% similar to the E. coli DsbD protein, a protein involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes (11). By analogy, the putative protein of P. citrea was called DsbD. A thioredoxin family active site characteristic of thiol-disulfide interchange proteins was also found between aa 484 and 512 at the C terminus of DsbD. Analysis of the sequences flanking dsbD revealed that it is surrounded by two genes showing more than 70% homology with cutA (upstream) and cutA3 (downstream) that are involved in copper tolerance in E. coli (15). No transcriptional terminator could be detected between the three genes, suggesting that they form an operon structure. To confirm that alteration of DsbD function is responsible for the pink− phenotype of mutant CP6C8, we introduced a plasmid containing the gene, pUCD5077, into strain CP6C8 and randomly selected four independent transformants. These transformants were tested for the ability to induce pink disease and were all able to color pineapple juice, albeit at 75% of the wild-type strain level (data not shown), showing that the defect in CP6C8 can be complemented solely by dshD.

Sequencing of the 103C11 and CP15E7 insertion sites demonstrated that Tn10 was inserted in 738-bp gene (nt 2174 to 2912) whose product would correspond to a 246-aa protein 82% similar to the CcmC protein of E. coli and was therefore called ccmC. The nucleotide sequence of a 7,130-bp fragment of pUCD5079 showed that ccmC belongs to a gene cluster highly homologous to the ccm cluster of E. coli which is required for cytochrome c maturation (41) (Fig. 3C). A total of eight genes could be identified around ccmC: ccmA (nt 851 to 1475), ccmB (nt 1468 to 2125), ccmC (nt 2174 to 2912), ccmD (nt 2911 to 3142), ccmE (nt 3141 to 3615), ccmF (nt 3624 to 5589), ccmG (nt 5588 to 6143), and ccmH (nt 6151 to 6706). All of those genes are very likely arranged in an operon structure, since no transcriptional terminator could be detected in the 7-kb sequence or after the 3′ end of the equivalent of the ccmH gene. As in E. coli, the start codon for ccmE would be GTG instead of the usual ATG. Except for ccmH, the genes of the cluster encode proteins whose size is equivalent to their counterparts in E. coli (Table 3). The putative CcmH protein of P. citrea is only 185 aa, while in E. coli it is 350 aa. However, CcmH of P. citrea is 60% similar, and closer in size, to the CycL protein of Pseudomonas fluorescens (156 aa), which is also required for the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes (42).

TABLE 3.

Similarity between P. citrea and E. coli ccm gene products

| Gene | No. of residues

|

% Similarity | % Identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. citrea | E. coli | |||

| ccmA | 208 | 205 | 67 | 57 |

| ccmB | 219 | 220 | 74 | 67 |

| ccmC | 246 | 245 | 82 | 75 |

| ccmD | 77 | 69 | 61 | 48 |

| ccmE | 158 | 159 | 75 | 66 |

| ccmF | 655 | 647 | 76 | 69 |

| ccmG | 185 | 185 | 83 | 75 |

| ccmH | 185 | 350 | 69a | 55a |

On 127 amino acid residues.

A plasmid containing the full-length ccmC gene, pUCD5094, was constructed and introduced into mutants 103C11 and CP15E7 for complementation assays. For randomly independent transformants were selected and tested for the ability to induce pink disease. All of them were able to color pineapple juice at a level identical to that for the wild-type strain, showing that a defect in CcmC was solely responsible for the inability to color pineapple juice (data not shown).

The fact that genes involved in cytochrome c maturation are responsible for the phenotype of mutants 103C11 and CP15E7 was also confirmed by complementation of these two strains with plasmid pEC2, which contains the whole ccm operon of E. coli (41). 103C11 and CP15E7 cells harboring pEC2 were able to color pineapple juice, although the intensity of the color was only 60% of that obtained with the wild-type strain (data not shown).

The pink− mutants are deficient for gluconate or 2-KDG dehydrogenase activity.

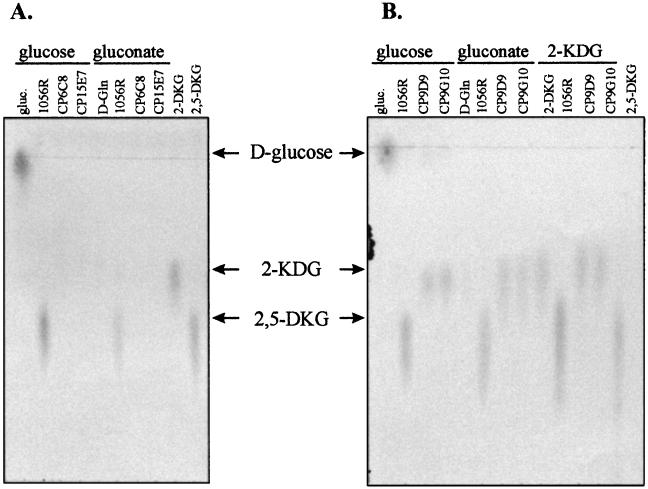

The pathway forming 2,5-DKG from d-glucose oxidation appears to be responsible for the coloration of pineapple juice. To determine directly at which step of the pathway the mutants were affected, CP6C8 (dsbD), CP15E7 (ccmC), and CP9D9 and CP9G10 (orfB) cells were assayed for gluconate dehydrogenase and 2-KDG dehydrogenase activities as described in Materials and Methods. No gluconate dehydrogenase activity was detected in mutant CP6C8 or CP15E7, while mutants CP9D9 and CP9G10 were able to oxidize d-Gln. However, mutants CP6C8 and CP15E7 were able to oxidize 2-KDG, while mutants CP9D9 and CP9G10 were not (data not shown). These results were confirmed by direct deletion of 2-KDG and 2,5-DKG by TLC. P. citrea wild-type strain 1056R and the above mutants were grown for 3 days in MGY medium supplemented with 50 mM d-glucose, d-Gln, or 2-KDG, and culture supernatants were analyzed by TLC (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 4, P. citrea 1056R accumulates 2,5-DKG when grown in the presence of d-glucose, d-Gln, or 2-KDG. When mutant strains CP6C8 and CP15E7 were grown in the presence of glucose or gluconate, only a weak light blue spot corresponding to gluconate was detected (data not shown); no spot characteristic of 2-KDG was detected. However, when these strains were grown in presence of 2-KDG, a spot corresponding to 2,5-DKG was visible, although to a lesser intensity than with the wild-type strain (data not shown; see Discussion). These results indicate that strains CP6C8 and CP15E7, deficient for dsbD and ccmC, respectively, are affected in their gluconate dehydrogenase activity and, to a lesser extent, in the ability to oxidize 2-KDG. In contrast, mutant strains CP9D9 and CP9G10, deficient in orfB, were able to product 2-KDG when grown in presence of glucose or gluconate but could not convert this compound to 2,5-DKG (Fig. 4B), confirming that they lack 2-KDG dehydrogenase activity. Taken together, these results demonstrate that production of 2,5-DKG by this pathway in P. citrea is responsible for pink disease of pineapple.

FIG. 4.

Qualitative detection of d-Gln, 2-KDG, and 2,5-DKG by TLC. P. citrea wild-type (1056R) and mutant strains were grown in MGY medium supplemented with 50 mM -d-glucose, d-Gln, or 2-KDG; 5μl of the culture supernatant were deposited on a Silica Gel 60 TLC plate and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Controls correspond to 5 μl of MGY supplemented with the corresponding sugar. The wild-type strain was able to accumulate 2,5-DKG when grown in the presence of d-glucose, d-Gln, or 2-KDG. (A) 1056R and mutants strains CP6C8 (dsbD) and CP15E7 (ccmC). Mutants CP6C8 and CP15E7 were able to produce only d-Gln. (B) 1056R and mutants strains CP9D9 and CP9G10 (orfB). These mutants are able to oxidize d-Gln to 2-KDG but are unable to accumulate 2,5-DKG. Arrows indicate the position of the running front of each sugar.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence for the presence of an oxidative pathway beginning with d-glucose and ending with 2,5-DKG in P. citrea. The end product, 2,5-DKG, is a highly chromogenic compound that turns intensely rusty red when heated and appears to be the primary contributor of the pink-to-red coloration associated with pink disease of pineapple.

The rationale behind this work was to identify the complete pathway leading to the economically important pink disease of pineapple at the molecular level, using transposon mutagenesis and biochemical assays. Previously, we showed that oxidation of d-glucose to d-Gln was required for the disease (7, 26). However, addition of -d-Gln in the medium could bypass the need for glucose dehydrogenase activity, indicating that the complete pathway included at least one additional step. In Erwinia sp., d-Gln can be converted to 2-keto gluconate or 5-keto gluconate by membrane-bound dehydrogenases linked to the cytochrome chain that release the products in the periplasmic space (33, 34, 37). We showed that sugars of the Entner-Doudoroff pathway, 5-DKG, l-gulonic acid, and sugars of the pentose phosphate pathway were not involved in the dark coloration by P. citrea (Fig. 1 and data not shown). However, 2-KDG allowed for an intense coloration of the medium by P. citrea, demonstrating that conversion of d-gluconate to 2-KDG was a second important step in the pathway (26). 2-KDG can then be further oxidized to 2,5-DKG. Interestingly, the addition of 2,5-DKG to the culture medium produced the red color characteristic of pink disease, even in the absence of bacterial growth, strongly suggesting that accumulation of 2,5-DKG by P. citrea is responsible for the coloration of pineapple juice (data not shown).

This scenario received strong support from our genetic screen of P. citrea mutants which are deficient in the ability to induce the disease. The first series of mutants, corresponding to strains CP6C8, 103C11, and CP15E7, are unable to oxidize d-Gln to 2-KDG and are therefore affected in their d-gluconate dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 4B). The second series of mutants, corresponding to strains CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2, are clearly deficient in the ability to convert 2-KDG to 2,5-DKG. The reason behind these deficiencies were, however, multiple and therefore allowed us to gain insight regarding the catabolism of glucose in P. citrea and the use of cytochromes c. c-type cytochromes are found in many respiratory chains and are usually located in the periplasm or attached to the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane (13, 14, 25). They serve as specific electron acceptors linked to various oxidation reactions, including those resulting from dehydrogenase activities (10, 12, 43).

Mutant strain CP6C8 (Fig. 3B) is inactivated in a gene potentially encoding a 578-aa protein that is very (70 to 80%) similar to the disulfide bond isomerase proteins DsbD and DipZ of E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae, respectively (data not shown). In E. coli, DsbD is involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes by maintaining cytochrome c apoproteins in the correct conformation for the covalent attachment of heme (11). In E. coli, DsbD is a cytoplasmic membrane protein with a thioredoxin-like domain at its C terminus, a domain that is also found in the DsbD protein of P. citrea (aa 484 to 512) (23). Mutant strains 103C11 and CP15E7 (Fig. 3C) are defective in a 738-bp gene showing 80% identity with the ccmC gene of E. coli. This gene is part of an eight-gene operon which shares significant homology, and a conserved structure, with the ccm operon of E. coli (Table 3). This operon encodes eight membrane-associated proteins required for cytochrome c maturation in E. coli (for a review, see reference 40). More specifically, CcmC is required for the transfer of the heme prosthetic group of c-type cytochrome to the newly synthesized apocytochrome c (31, 32). Taken together, these three mutant trains are affected in genes involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes.

In P. citrea, a defect in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes is responsible for a failure of gluconate dehydrogenase activity. It is worth mentioning that when 2-KDG was added to the growth medium of these mutant cells, only a small amount of 2,5-DKG was detected, indicating that c-type cytochromes might also be involved in 2-KDG dehydrogenase activity (data not shown). In contrast, d-glucose dehydrogenase activity was not affected in these mutants, in agreement with our previous results showing that this reaction uses pyroloquinoline quinone as an electron acceptor (26).

Mutant strains CP9D9, CP9G10, and 105D2 are affected in a putative 1,659-bp gene (orfB) that appears to be part of a three-gene operon (Fig. 3A and 4). The corresponding protein, OrfB, shared 34% similarity with the E. cypripedii membrane-bound gluconate dehydrogenase. In this organism, the gluconate dehydrogenase is thought to be composed of three subunits corresponding to the dehydrogenase itself, a cytochrome c subunit, and a third small subunit of unknown function (43). A similar organization has also been reported for Gluconobacter dioxyacetonicus (34). Interestingly, the product of the third gene of the P. citrea operon, OrfC, shows 60% similarity to the cytochrome c subunit of the E. cypripedii gluconate dehydrogenase complex (43), as well as to the A. aceti alcohol dehydrogenase (38). This finding, together with our results regarding the phenotype of the orfB mutations, allows us to suggest that the P. citrea operon encodes for a three-subunit, 2-keto-d-gluconate dehydrogenase. This enzyme therefore carries out the last step of the pathway leading to the accumulation of 2,5-DKG, the likely cause of the dark coloration of pineapple.

A way to confirm the hypothesis that the accumulation of 2,5-DKG by P. citrea is the cause of the pink coloration is to use a 2,5-DKG reductase that would catalyze conversion of 2,5-DKG to 2-keto-l-gulonic acid (2-KLG), as is observed in a number of organisms such as Corynebacterium sp. (3, 36). 2-KLG can then be further reduced to gulonic acid, which is not a substrate for coloring the medium (data not shown). For this purpose, we introduced plasmid pTrp1-35 containing the 2,5-DKG dehydrogenase from Corynebacterium sp. (3, 21) into P. citrea and found that transformants still retained the ability to color pineapple juice (data not shown). This negative result can be interpreted in several ways. One possibility is that the Corynebacterium sp. 2,5-DKG reductase does not efficiently reduce 2,5-DKG to 2-KLG in P. citrea. In support of this possibility, the 2,5-DKG reductase used here, 2,5-DKG reductase I, has a specific activity 33 times lower than that of the 2,5-DKG reductase II from Corynebacterium sp. used by Grindley et al. to convert glucose to 2-KLG in a recombinant strain of P. citrea (16). This might explain why 2,5-DKG was not efficiently reduced in our experiments. A second possibility is that P. citrea possesses enzymes that efficiently reduce 2-KLG to idonate and 2-KDG to gluconate, which in effect would produce even more substrate for the 2-KDG dehydrogenase. Indeed, some 2-KDG reductases from acetic acid bacteria are able to catalyze the reduction of 2-KLG to l-idonate and are also able to reduce 2-KDG to d-gluconate (2, 44). In support of this possibility, kinetics experiments showed that 2,5-DKG accumulated even faster in the presence of plasmid pTrp1-35 (data not shown). Therefore, the failure of our attempt to eliminate accumulation of 2,5-DKG does not disprove our initial suggestion.

In conclusion, we have described new genes in P. citrea that are involved in the coloration of pineapple juice. These genes allowed the identification of the biochemical pathway leading to the production of 2,5-DKG, which we now identify as the chromogenic compound responsible for the dark color characteristic of pink disease of pineapple.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Alexeyev and L. Thöny-Meyer for kindly providing plasmids pBSL346 and pEC2, respectively. We appreciate Stephen Anderson for providing plasmid pTrp135-A. We thank Peter Pujic for supplying 2,5-DKG and gulonic acid and for helpful discussion. We are grateful to Frédéric Chédin and Timothy Durfee for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Natalie Macher and Viet Pham for technical help.

This work was sponsored by Dole Philippines, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexeyev M F, Shokolenko I N. Mini-Tn10 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and gene delivery into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1995;160:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameyama M, Adachi O. 2-Keto-d-gluconate reductase from acetic acid bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1982;89:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)89033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson S, Marks C B, Lazarus R, Miller J, Stafford K, Seymour J, Light D, Rastetter W, Estell D. Production of 2-keto-l-gulonate, an intermediate in l-ascorbate synthesis, by a genetically modified Erwinia herbicola. Science. 1985;230:144–149. doi: 10.1126/science.230.4722.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C. A rapid alkaline extraction method for the isolation of plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1983;100:243–255. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvet O M, Lenormand P, Grimont P A. Taxonomic diversity of the d-glucose oxidation pathway in the enterobacteriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha J-S, Pujol C J, Kado C I. Identification and characterization of a Pantoea citrea gene encoding glucose dehydrogenase that is essential for causing pink disease of pineapple. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:71–76. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.71-76.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha J-S, Pujol C J, Ducusin A R, Macion E A, Hubbard C H, Kado C I. Studies on Pantoea citrea, the causal agent of pink disease of pineapple. J Phytopathol. 1997;145:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleton-Jansen A-M, Goosen N, Wenzel T J, van de Putte P. Cloning of the gene encoding quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: evidence for the presence of a second enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2121–2125. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2121-2125.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox J M, Day D J, Anthony C. The interaction of methanol dehydrogenase and its electron acceptor, cytochrome cL in methylotrophic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1119:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90240-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crooke H, Cole J. The biogenesis of c-type cytochromes in Escherichia coli requires a membrane-bound protein, DipZ, with a protein disulphide isomerase-like domain. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1139–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duine J A, Frank J, De Ruiter L G. Isolation of a methanol dehydrogenase with a functional coupling to cytochrome c. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;115:523–526. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson S J. Cytochrome c springs a surprise. Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson S J. Periplasmic electron transport reactions. In: Anthony C, editor. Bacterial energy transduction. London, England: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 151–182. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong S T, Camakaris J, Lee B T. Molecular genetics of a chromosomal locus involved in copper tolerance in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1127–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grindley J F, Payton M A, van de Pol H, Hardy K G. Conversion of glucose to 2-keto-l-gulonate, an intermediate in l-ascorbate synthesis, by a recombinant strain of Erwinia citreus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1770–1775. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1770-1775.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauge J G. Glucose dehydrogenase: Pseudomonas sp. and Bacterium anitratum. Methods Enzymol. 1966;9:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hine R B. Epidemiology of pink disease of pineapple fruit. Phytopathology. 1975;66:323–327. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joveva S, Nozinie R, Delie V. Determination of intermediates in bioconversion of 2,5-diketo-d-gluconic acid by genus Corynebacterium by thin-layer chromatography. Prehrambeno-tehnol Biotehnol Rev. 1991;29:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kageyama B, Nakae M, Yagi S, Sonoyama T. Pantoea punctata sp. nov., Pantoea citrea sp. nov., and Pantoea terrea sp. nov. isolated from fruit and soil samples. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:203–210. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khurana S, Powers D B, Anderson S, Blaber M. Crystal structure of 2,5-diketo-d-gluconic acid reductase A complexed with NADPH at 2.1-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6768–6773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyon H L. A survey of the pineapple problems. Hawaii Plant Rec. 1915;13:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Missiakas D, Schwager F, Raina S. Identification and characterization of a new disulfide isomerase-like protein (DsbD) in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1995;14:3415–3424. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxenham B L. Diseases of the pineapple. Queensl Agric J. 1957;83:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettigrew G W, Moore G R. Cytochromes c. Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin; 1987. pp. 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujol C J, Kado C I. gdhB, a gene encoding a second quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase in Pantoea citrea, is required for the pink disease of pineapple. Microbiology. 1999;145:1217–1226. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohrbach K G. Unusual tropical fruit diseases with extended latent periods. Plant Dis. 1989;73:607–609. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohrbach K G, Pfeiffer J B. The interaction of four bacteria causing pink disease of pineapple with several pineapple cultivars. Phytopathology. 1976;66:396–399. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz H, Fabianek R A, Pellicioli E C, Hennecke H, Thöny-Meyer L. Heme transfer to the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation requires the CcmC protein, which may function independently of the ABC-transporter CcmAB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6462–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz H, Hennecke H, Thöny-Meyer L. Prototype of a heme chaperone essential for cytochrome c maturation. Science. 1998;281:1197–1200. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinagawa E, Chiyonobu T, Matsushita K, Adachi O, Ameyama M. Distribution of gluconate dehydrogenase and ketogluconate reductases in aerobic bacteria. Agric Biol Chem. 1978;42:1055–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinagawa E, Matsushita K, Adachi O, Ameyama M. d-Gluconate dehydrogenase, 2-keto-d-gluconate yielding, from Gluconobacter dioxyacetonicus: purification and characterization. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;48:1517–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vitro engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:742–791. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonoyama T, Kobayashi B. Purification and properties of two 2,5-diketo-d-gluconate reductases from a mutant strain derived from Corynebacterium species. J Ferment Technol. 1987;65:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonoyama T, Yagi S, Kageyama B. Facultatively anaerobic bacteria showing high productivities of 2,5-diketo-d-gluconate from d-glucose. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:667–674. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamaki T, Fukaya M, Takemura H, Tayama K, Okumura H, Kawamura Y, Nishiyama M, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Cloning and sequencing of the gene cluster encoding two subunits of membrane-bound alcohol dehydrogenase from Acetobacter polyoxogenes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1088:292–300. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90066-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.te Riele H, Michel B, Ehrlich S D. Single-stranded plasmid DNA in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2541–2545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thöny-Meyer L. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Rev. 1997;61:337–376. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.337-376.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thöny-Meyer L, Fischer F, Kunzler P, Ritz D, Hennecke H. Escherichia coli genes required for cytochrome c maturation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4321–4326. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4321-4326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang C, Azad H, Cooksey D. A chromosomal locus required for copper resistance, competitive fitness, and cytochrome c biogenesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yum D Y, Lee Y P, Pan J G. Cloning and expression of a gene cluster encoding three subunits of membrane-bound gluconate dehydrogenase from Erwinia cypripedii ATCC 29267 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6566–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6566-6572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yum D-Y, Lee B-Y, Hahm D-H, Pan J-G. The yiaE gene, located at 80.1 minutes on the Escherichia coli chromosome, encodes a 2-ketoaldonate reductase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5984–5988. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5984-5988.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]