Summer hay fever causes considerable morbidity and affects quality of life at a time usually considered as the best of the year. Its prevalence has increased over the past 20 years despite falling pollen counts.

Antihistamines and nasal corticosteroid sprays are first line treatment

Environmental triggers

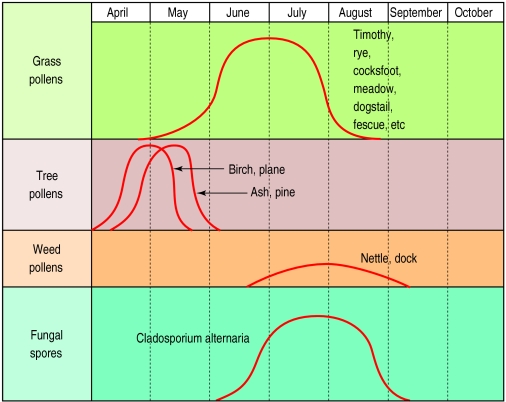

The main cause of hay fever in Britain is grass pollen, particularly perennial rye (Lolium perenne) and timothy grass (Phleum pratense). Symptoms peak during June and July. Symptoms in spring are commonly due to tree pollens, whereas symptoms in late summer and autumn may be due to weed pollens and mould spores. Rape seed may also provoke symptoms of rhinitis, although usually through irritant rather than allergic mechanisms. It has been suggested that emissions of nitrogen dioxide and ozone from vehicle exhausts have been increasing the sensitivity to airborne allergens.

Mechanisms of rhinitis

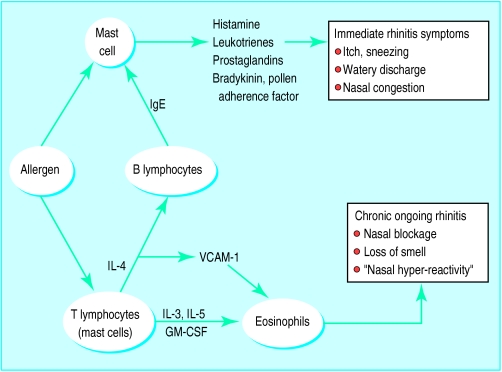

The symptoms of rhinitis are caused by an interaction between grass pollen and IgE on the surface of sensitised mucosal mast cells (type 1 hypersensitivity). The cells release mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes, which produce itch, sneeze, watery anterior nasal discharge, nasal congestion, and symptoms affecting the eyes.

Allergens are also recognised and processed by mucosal dendritic cells (Langerhans’ cells) or macrophages, which then stimulate T lymphocytes to release interleukins, which promote tissue eosinophilia and IgE production. These compounds act to produce ongoing rhinitis, symptoms of blockage, impaired sense of smell, and nasal hyperreactivity (an exaggerated nasal response to environmental irritants such as cold air, perfume, or tobacco smoke).

Diagnosis

Most patients present with the diagnostic symptoms of seasonal itching, sneezing, watery nasal discharge, and associated eye problems. The nose may be examined with an auriscope to exclude a structural problem. Skin prick tests are not usually needed for diagnosis, but a positive result may help to reinforce advice to take topical prophylaxis.

Diagnosis of hay fever

| History | Prominent itch or sneezing and associated eye symptoms |

| Pale, bluish, swollen mucosa (only if symptomatic at time) | |

| Not essential, although of educational value and reinforces oral advice | |

| Nasal examination | |

| Skin prick test or radioallergosorbent test | |

BMJ 1988;316:843-5

Drug treatment

Antihistamines

Oral antihistamines are effective in patients with mild to moderate disease, particularly in those whose main symptoms are palatal itch, sneezing, rhinorrhoea, or eye symptoms. Antihistamines have little effect, however, on nasal blockage.

Diagnosis of summer hay fever is usually straightforward

Terfenadine and astemizole are the most commonly prescribed drugs, are effective, and rarely cause drowsiness or anticholinergic side effects. With these drugs it is important to emphasise the manufacturers’ instructions in view of the extremely rare complication of cardiac arrhythmias in overdose and, in the case of terfenadine, interactions with erythromycin or ketoconazole (which should not be given concurrently).

Newer alternatives include loratadine and fexofenadine. Acrivastine is short acting and may be useful when symptoms are mild and episodic. Cetirizine has also been shown to be highly effective in placebo controlled trials. The place of topical nasal antihistamines in hay fever is currently being evaluated.

Stepwise approach to treatment of summer hay fever

Allergen avoidance (if appropriate)

Mild disease or with occasional symptoms

Rapid onset, oral, non-sedating histamine H1 antagonists when the patient is symptomatic; or

Antihistamine or cromoglycate topically to eyes or nose, or both

Moderate disease with prominent nasal symptoms

Topical nasal steroid daily (start early in the season); plus

Antihistamine or cromoglycate topically to eyes

Moderate disease with prominent eye symptoms

Oral, non-sedating histamine H1 antagonists daily; or

Topical nasal steroid and sodium cromoglycate topically to eyes

If above are ineffective, check compliance and consider:

Nasal examination

Allergy tests

Additional pharmacotherapy—for example, short course of oral steroids

Immunotherapy (requires referral to specialist)

Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are extremely potent, with a low potential for systemic side effects. They are the best treatment for patients with moderate to severe nasal symptoms. Aqueous corticosteroids are better tolerated than those in fluorocarbon propellants and have a better local distribution in the nose. The side effects are minor—local irritation and occasional (in 5% of cases) bleeding. Treatment should be started before the beginning of the hay fever season for maximal effect. Patients should be given instruction on the importance of regular treatment and how to use the nasal spray.

Topical corticosteroids are effective against all nasal symptoms, including nasal blockage. Although systemic absorption is negligible in adults, care should be taken when nasal steroids are given to children who are also taking inhaled steroids for asthma or topical steroids for eczema. Sodium cromoglycate two to four times daily is an alternative, particularly in children. Eye drops containing sodium cromoglycate, such as Opticrom, are effective in most patients (often within minutes) for allergic symptoms affecting the eyes.

Effects of drugs on nasal symptoms in adults

| Itch or sneezing | Discharge | Blockage | Impaired smell | |

| Topical corticosteroids | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Oral antihistamines | +++ | ++ | +/− | − |

| Sodium cromoglycate* | + | + | +/− | − |

| Ipratropium bromide | − | +++ | − | − |

| Topical decongestants | − | − | +++ | − |

| Oral corticosteroids | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

*First line treatment in children.

Second line treatment

In patients who fail to respond to antihistamines or topical corticosteroids, a short course of an oral corticosteroid (say, prednisolone 20 mg for five days) may produce rapid relief of symptoms. This is particularly effective when the nose is completely obstructed as topical treatment will not gain access to the nose.

An alternative is to use a topical decongestant short term to allow penetration of topical corticosteroids. Ipratroprium bromide may have a role when watery rhinorrhoea is pronounced.

In general it is important to establish which are the patient’s dominant symptoms and, particularly for severe symptoms, to match the treatment to the symptoms.

Avoiding allergens

Patients with allergies are usually advised to avoid the provoking allergen. It is, however, controversial whether this should be routinely recommended for pollen allergy. As hay fever is usually not severe or life threatening, drugs can allow patients to lead a normal life without unnecessary restrictions. But patients with debilitating symptoms may benefit from simple advice. Pollen counts at ground level are highest during the evening and at night, when open grassy spaces should be avoided.

How to avoid pollen

Keep windows in cars and buildings shut

Wear glasses or sunglasses

Avoid open grassy places, particularly in the evening and at night

Use a car with a pollen filter

Check for pollen counts in the media

During the peak season take a holiday by the sea or abroad

Grass pollen immunotherapy

Immunotherapy should be considered in patients with summer hay fever uncontrolled by antiallergy drugs

It should be administered only in hospital or specialised clinics with immediate access to resuscitative facilities

Patients should be kept under observation for the first 60 minutes after injections

Patients with asthma should not be given grass pollen immunotherapy

Allergen extracts used should be biologically standardised

Immunotherapy

Most patients with hay fever will have their symptoms controlled by the above measures. Patients whose symptoms remain uncontrolled may benefit from “allergen injection immunotherapy.” This form of treatment is performed only in specialised centres. Careful selection of patients for this treatment is essential, and immunotherapy is contraindicated in those with chronic asthma. Indications and guidelines for immunotherapy in Britain were the subject of a recent report by the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Further reading

Howarth PH. Allergic rhinitis: a rational choice of treatment. Respir Med 1989;83:179-88

Naclerio RM. Allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med 1991;325:860

Lund V on behalf of the International Rhinitis Management Working Group. International consensus report on the diagnosis and management of rhinitis. Allergy 1994;49(suppl 19):1-34

Frew AJ on behalf of a British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology Working Party. Injection immunotherapy. BMJ 1993;307:919-22

Figure.

Perennial rye grass (Lolium perenne)—common in Britain

Figure.

Pollen calendar for Britain

Figure.

Hypothesis on mechanisms of summer hay fever (rationale basis for treatment). IL=interleukin, VCAM=vascular cell adhesion molecules, GM-CSF=granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

Acknowledgments

The pollen calendar is adapted with permission from Varney (Clin Exp Allergy 1991;21:757). The diagram showing the mechanisms of summer hay fever and the box on the stepwise approach to the treatment are adapted with permission from Lund et al (Allergy 1994;49(suppl 19):1-34).

Footnotes

The ABC of allergies is edited by Stephen Durham, honorary consultant physician in respiratory medicine at the Royal Brompton Hospital, London. It will be published as a book later in the year.