Abstract

Yersinia enterocolitica yplA encodes a phospholipase required for virulence. Virulence genes are often regulated in response to environmental signals; therefore, yplA expression was examined using a yplA::lacZY transcriptional fusion. Maximal yplA expression occurred between pH 6.5 and pH 7.5 and was induced in the mid-logarithmic growth phase. Potential Fnr, cyclic AMP (cAMP)-cAMP receptor protein (Crp), and ςF regulatory sites were identified in the nucleotide sequence. Reduction of yplA expression by aeration, addition of glucose and sucrose, and application of high temperature and salt is consistent with Fnr-, cAMP-Crp-, and ςF-mediated regulation, respectively. Expression of yplA was reduced in flhDC and fliA null strains, indicating that yplA is part of the flagellar regulon.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a human pathogen and a causative agent of gastroenteritis which is transmitted by the oral-fecal route (8). As is frequently true of gastrointestinal parasites, Y. enterocolitica is capable of prolonged survival outside a human host, in soil and water at temperatures as low as 4°C (9). Consequently, it has adapted to grow in two environments, in nutrient-limited natural environs at ambient temperature and in a generally nutrient-rich host at 37°C. The adaptation to a dual lifestyle is reflected by temperature regulation of Y. enterocolitica metabolism (prototrophic at <30°C, auxotrophic at 37°C), motility, O-antigen structure, and virulence genes (9, 13, 34, 37).

Expression of the virulence genes ail, inv, yst, yadA, and myfA; the ysc type III secretion system; and the yop genes is affected by temperature (11, 13, 22, 25, 29, 34, 37–39). Notably, the yst and inv virulence genes are expressed poorly at 37°C unless the bacteria are grown under conditions of greater osmolarity or lower pH, respectively (34, 37). Motility is also affected by temperature: Y. enterocolitica is motile at low temperatures (<30°C) (10). Interestingly, characterization of flagellar regulation has demonstrated that some Y. enterocolitica flagellar genes are regulated in response to temperature, yet others are not. Increasing the temperature above 30°C quickly repressed transcription of the fleABC class III flagellar genes in vitro (23). The flagellar sigma factor (ςF or FliA) directs transcription of class III genes, and fliA itself is temperature regulated (24). However, transcription of the class II flagellar genes flhBAE was unaffected by a shift to 37°C (14). By analogy to Escherichia coli and salmonellae, class II flagellar proteins form a transmembrane structure which serves as the flagellar type III secretion apparatus (1). Considering that a functional flagellum is not made at 37°C, it is unclear why some flagellar genes would be expressed unless (i) this partial flagellar structure served another purpose or (ii) being able to quickly complete the partial flagellum is advantageous in case conditions change. A recent study suggested that the flagellar basal body (encoded by class II genes) is able to function as a type III-like secretion apparatus, and this may account for the function of this structure at 37°C in the absence of a flagellum (49).

Previous experiments have established that the Y. enterocolitica phospholipase (YplA) is a virulence factor that influences the ability of Y. enterocolitica strain 8081v (39) and its derivatives to colonize tissues and to induce a more vigorous inflammatory response (41). To better understand the role of this phospholipase in pathogenesis, we characterized the pattern of yplA expression in Y. enterocolitica strains derived from 8081v (Table 1) in response to environmental conditions, especially those conditions which affect the expression of other known virulence factors. In addition, we examined the possibility that yplA is regulated as part of the flagellar regulon because it has a potential flagellar ςF promoter and it has been demonstrated that the phospholipase is secreted through the flagellar type III secretion system (49).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica strains | ||

| 8081v | Serovar O:8 wild type; pYVO8+ PLA+ Nalr | 39 |

| JB580v | pYVO8+ ΔyenR (R− M+) derivative of 8081v; PLA+ Nalr | 26 |

| 8081c | pYVO8− derivative of 8081v; PLA+ Nalr | 39 |

| YEDS10 | pYVO8+yplA::pEP185.2 PLA− Nalr | 41 |

| YEDS16 | pYVO8+yplA::lacZY PLA+ Nalr | This work |

| GY460 | JB580v ΔflhDC PLA− Nalr | 50 |

| YEDS29 | GY460 yplA′::lacZY PLA− Nalr | This work |

| JB400v | JB580v ′fliA PLA− Nalr | 2 |

| YEDS18 | JB400v yplA::lacZY PLA− | This work |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F′ endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA(Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] | 31 |

| S17-1 λpir | pro thi hsdR514 (R+ M−) ΔrecA integrated RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Kn::Tn7 (Tpr Strr) | 42 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDHS20 | 6.0-kb HindIII fragment harboring yplAB in pUC19; Ampr | 41 |

| pDHS21 | Same 6.0-kb fragment in opposite orientation in pUC19; Ampr | This work |

| pDHS28 | 1.7-kb AvaI/NheI fragment harboring yplA in pMal-p2; Ampr | This work |

| pEP185.2 | mob+ of pACYC184 with R6K origin; Cmr | 37 |

| pFUSE | lacZYA′ derivative of pPEP185.2; Cmr | 3 |

| pDHS45 | 2.2-kb NheI/XbaI fragment harboring region 5′ to yplA in pFUSE to give yplXA′::lacZY; Cmr | This work |

| pTM100 | mob+ derivative of pACYC184; Cmr Tetr | 33 |

| pGY10 | 4.3-kb EcoRI fragment harboring flhDC in pTM100; Tetr | 50 |

| pJB222 | 2.2-kb EcoRV fragment harboring fliA in pTM100; Cmr Tetr | 2 |

pYVO8+ strains carry the virulence plasmid of the O:8 serovar; pYVO8− strains do not. PLA+ indicates that the strain produces phospholipase activity on plates; PLA− indicates that the strain does not.

Sequence analysis of the yplAB promoter region.

The nucleotide sequence was scanned for potential regulatory sequences that might influence yplA expression; this required additional sequence information upstream of yplAB (GenBank accession no. AF0678496). The template pDHS20 (41) was purified by the alkaline lysis method (31), sequenced using the ABI Prism Bigdye Terminator Cycle Sequencing System (Perkin-Elmer), and read on an ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer (Nucleic Acid Chemistry Laboratory, Washington University). Sequence analysis using the Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package (GCG, Madison, Wis.) indicated that the arrangement of genes and their predicted amino acid sequences are very similar to those in the phlAB locus of Serratia liquefaciens (41). S. liquefaciens phlAB encodes a phospholipase A1 and its putative accessory protein, respectively (18, 19). Located 221 bp upstream of yplAB is another open reading frame, yplX, transcribed from the same strand as yplAB. The predicted amino acid sequence of Y. enterocolitica yplX is 90% identical (over 111 residues) to that of similarly placed orfX found in S. liquefaciens (17), as well as 85 and 83% identical to hypothetical proteins encoded in E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae (6, 15). All of these small proteins share significant identity (80% identity over 61 residues) with the acetyltransferase domain of E. coli pyruvate formate lyase (formate acetyltransferase) (48). Further examination of the Y. enterocolitica nucleotide sequence indicated that divergently transcribed genes flank the hypothetical acetyltransferase yplX and yplAB, suggesting that the maximal possible transcriptional unit is restricted to yplXAB.

Examination of the upstream regions for potential regulatory sequences such as promoters and regulatory protein binding sites has identified several regions of interest. Preceding yplX by 113 bp is a sequence with similarity to the binding site consensus for Fnr (46). Fnr is a global activator of genes expressed under anaerobic conditions that is itself oxygen sensitive (4). Examination of the intergenic sequence between yplX and yplA had confirmed a potential binding site for flagellar sigma factor ςF (FliA) (21, 41) and Crp (7). The potential ςF and Crp binding sites are located 55 and 92 bp upstream of yplA, respectively. FliA (ςF) is the alternate sigma factor that directs transcription of class III flagellar genes. Crp is a global regulator that responds to cytoplasmic cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels (7). Comparison of the intergenic sequences of Y. enterocolitica and S. liquefaciens determined that regions with the highest identity encompass the potential regulatory sites. Matches to Fnr, cAMP-Crp, and ςF binding sites were found similarly positioned in the S. liquefaciens nucleotide sequence (17). Furthermore, expression of Serratia phlAB was shown to be dependent on functional cya (adenylate cyclase) and flhDC genes in E. coli (17). The pattern of phlAB regulation in S. liquefaciens was consistent with catabolite repression (inhibition by glucose) and was shown to require functional flhD (16, 17).

Environmental signals affecting yplAB expression.

The Y. enterocolitica reporter strain YEDS16 was generated with yplA::lacZY located in the appropriate chromosomal environment in single copy to reflect expression of yplA (Fig. 1). YEDS16 is a merodiploid with a fully intact yplX yplAB (yplXAB) region with another copy of yplXA′ transcriptionally fused to lacZY. To generate a transcriptional fusion in the Yersinia chromosome, pDHS45 (yplA′::lacZY) was mated into Y. enterocolitica strain JB580v (26) as previously described (42). pDHS45 replicates from an R6K origin; thus, it can only be stably maintained if the plasmid integrates into the chromosome by homologous recombination (27, 42). Y. enterocolitica transconjugants were selected on Luria broth (LB) supplemented with nalidixic acid at 20 μg/ml and chloramphenicol at 25 μg/ml. This strain, YEDS16, was found to be β-galactosidase and phospholipase positive on plates (1% tryptone agar or MacConkey agar base) incubated at 26°C supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside at 20 μg/ml or 0.2% egg yolk lecithin and 1 mM CaCl2, respectively (data not shown); under the same conditions, 8081v is also positive on lecithin plates (41). This is consistent with the functional phospholipase promoter being duplicated and driving lacZY and yplAB expression in YEDS16.

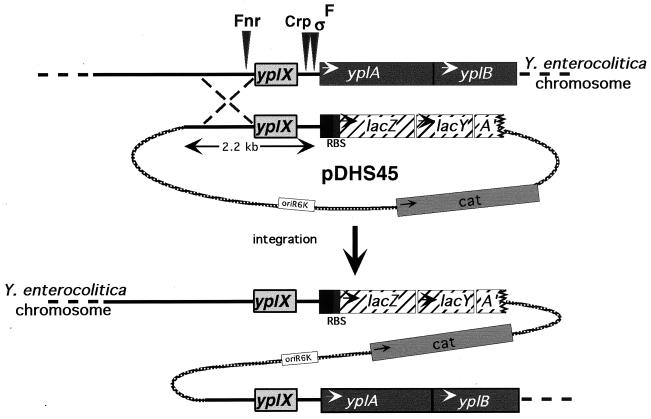

FIG. 1.

Integration of pDHS45 into the Y. enterocolitica chromosome (above) with resolution of the homologous recombination event (below) to generate a chromosomal reporter fusion. The coding regions of the phospholipase, yplA, its putative accessory protein, yplB, and the hypothetical acetyltransferase, yplX, are depicted as boxes. In the boxes, arrows indicate the direction of transcription and the positions of predicted regulatory protein binding sites are indicated by labeled arrowheads in the normal locus diagrammed at the top. The suicide plasmid pDHS45 carries a 2.2-kb XbaI/NheI fragment from pDHS21 that encompasses sequences 5′ to yplA and was ligated into the unique XbaI site adjacent to the intact lacZY genes (with a ribosomal binding site) on the suicide vector pFUSE (3). The functional yplAB locus is encoded within pDHS21 (this study; yplAB is in the opposite orientation within previously described plasmid pDHS20 [41]). The yplAB region diagrammed is present in strains YEDS16, YEDS18, and YEDS29. Plasmid sequences are indicated by the broken line; the solid line indicates Yersinia sequences. The correct insertion of yplA′::lacZY (on pDHS45) was confirmed by Southern analysis (45) of SphI and EcoRI digests of chromosomal DNA purified as previously described (32) using a yplA fragment as a probe (data not shown). A 662-bp fragment of yplA was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′ AAGAACTCATCCGATGTG 3′ and 5′ AGTGCATCGACCAAATGCC 3′.

An initial observation indicated that levels of phospholipase activity produced by Y. enterocolitica decreased when salt was added to the medium (when assayed on lecithin plates). Consistent with this observation, comparison of the β-galactosidase activity produced by overnight cultures of the reporter strain, YEDS16, grown in either 1% tryptone broth, 1% tryptone with 200 mM NaCl, or LB (which contains 171 mM NaCl) determined that yplA expression was greatest in the 1% tryptone broth cultures (data not shown). β-Galactosidase assays were performed and values were calculated as previously described (35). This finding suggests that the inhibitory effect of salt on YplA activity is exerted at the transcriptional level. Thereafter, all experiments used Y. enterocolitica cultures grown in 5 ml of 1% tryptone broth based media under standard conditions, i.e., incubation in a culture tube on a wheel at 26°C for 8 h, unless otherwise indicated. Cultures for determination of yplA expression were inoculated from overnight LB cultures, conditions known to produce very low levels of yplA expression. Thus, residual β-galactosidase activity from the overnight cultures would not be detected in the samples assayed. The inhibitory effect of NaCl was further examined to distinguish among several possible environmental cues which might be causing the effect: NaCl concentration, ionic strength, and osmolarity (Fig. 2A). The effects of ionic strength versus osmolarity were tested in 1% tryptone broth supplemented with increasing salt (0 to 300 mM KCl or NaCl) or rhamnose (0 to 600 mM) concentrations, as indicated. The level of β-galactosidase activity (yplA expression) decreased similarly with increasing concentrations of NaCl and KCl, but only the highest concentration of rhamnose (600 mM) caused significant repression. Thus, the environmental cue triggered by NaCl seems to be either chloride concentration or ionic strength generally rather than osmolarity, although high osmotic strength is also apparently inhibitory.

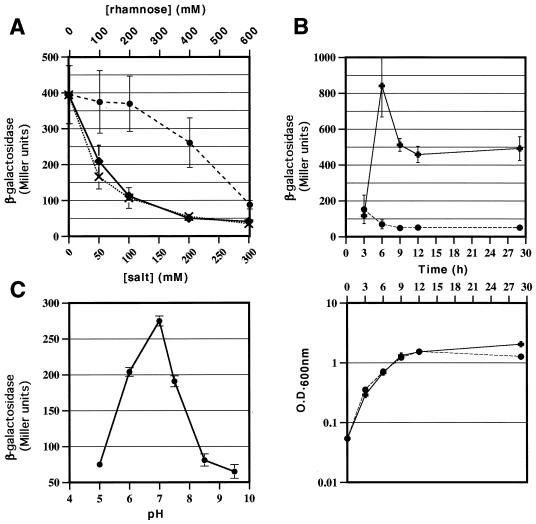

FIG. 2.

Effects of ionic strength and osmolarity (A), growth phase and temperature (B), and pH (C) on β-galactosidase activity production by yplA′::lacZY present in Y. enterocolitica YEDS16. (A) Cultures were grown at 26°C for 8 h in 1% tryptone supplemented with the concentrations of NaCl (⧫, solid line) and KCl (×, dotted line) indicated on the bottom x axis and the concentrations of rhamnose (●, hashed line) indicated on the top x axis. β-Galactosidase activity is shown on the y axis in Miller units. The OD600 of the cultures in these media were comparable after 8 h, except for those with 400 or 600 mM added rhamnose, in which YEDS16 grew slower. (B) Cultures were grown in 1% tryptone at 26°C (✚, solid line) and at 37°C (●, hashed line) for 29 h, and samples were taken initially every 3 h. The top graph plots the β-galactosidase activity on y axis (Miller units) versus time (h) on the x axis. The bottom graph depicts bacterial growth over time for the same cultures. OD600 is plotted on the y axis, and time is on the x axis. (C) A series of buffered 1% tryptone broth cultures (50 mM buffer, pH range of 5.0 to 9.5) were inoculated from the same overnight YEDS16 LB cultures and incubated for 8 h at 26°C. The final pH of the buffered media was determined and found not to change during the course of the experiment. The OD600 of the cultures in the buffered media were comparable after 8 h, except for that of the pH 9.5 medium, which had a lower OD600. Consequently, the cultures in pH 9.5 medium were allowed to grow for an additional 4 h; the β-galactosidase activities at 8 and 12 h were similar, even though the 12-h culture had a greater OD600. The standard deviation of the mean is represented as error bars for each plotted point.

The level of expression was monitored at various times during the growth of YEDS16 to determine at which phase of growth yplA is most highly expressed (Fig. 2B). β-Galactosidase activity peaked during mid-to-late logarithmic phase, but significant activity was detected late into stationary phase. Induction of expression at the transition from logarithmic growth to stationary phase has been demonstrated for other virulence genes, including inv, yst, ail, and myfA (22, 34, 37, 38). Although the initial increase of yplA transcription is initiated in late log phase, significant transcriptional activity continues well into stationary phase.

Experiments examining phospholipase activity produced by Y. enterocolitica on lecithin plates established that phospholipase activity was produced at 26°C but was not detected at 37°C. There are several possible explanations for this temperature effect: yplA may not be efficiently transcribed, YplA may not be efficiently secreted, or YplA is not active at 37°C. Active phospholipase had been produced from a high-copy plasmid in E. coli grown at 37°C, suggesting that YplA is active at 37°C, which is consistent with the role of YplA as a virulence factor (data not shown). To determine whether the temperature effect was due to transcriptional regulation, YEDS16 was grown at 37°C and assayed for β-galactosidase activity at various times during growth (Fig. 2B). In vitro, there was no significant induction of expression in 1% tryptone at 37°C at any phase of growth. Therefore, the lack of phospholipase activity displayed by Y. enterocolitica in vitro at 37°C is due to temperature regulation at the level of transcription.

Superficially, this pattern of temperature regulation is contradictory to the role of YplA as a virulence factor. However, inv (invasin) and yst (heat-stable enterotoxin) are also virulence genes expressed at low temperature rather than at 37°C in vitro (13). Yet, at slightly acidic pH or high osmolarity, respectively, these virulence genes are expressed at 37°C in vitro (34, 37). Moreover, invasin has been detected in yersiniae recovered from mouse tissues 45 h after peroral inoculation in amounts similar to those produced by the same number of bacteria cultured at 26°C in vitro (37). Therefore, high-temperature repression can be superseded by other conditions that stimulate expression in the host. Alternatively, low-temperature induction could reflect the need for the virulence factors early in the infectious process, as has been suggested for invasin (37) and the Y. enterocolitica urease (12). Invasin is thought to promote initial entry through the intestinal epithelium, and urease is thought to promote survival in the acidic environment of the host stomach. However, a secreted virulence factor would likely be diluted or degraded and exert little effect unless produced and secreted within the host. Thus, it seems probable that some cue induces expression of yplA in vivo. Future experiments will attempt to demonstrate the presence of YplA or expression of yplA in yersiniae infecting mouse tissues, but that is beyond the scope of this study.

A number of important Yersinia virulence genes, the yop genes and yadA, are expressed under low-calcium conditions at 37°C in vitro (39). Experiments with YEDS16 demonstrated that removal of calcium by addition of 20 mM NaC2O4 and 20 mM MgCl2 at 26°C slightly repressed expression of yplA, but addition of extra Ca2+ (2.5 mM CaCl2) had no significant effect (data not shown). There was no apparent effect of calcium limitation at 37°C, although Y. enterocolitica does not grow well at elevated temperature without calcium. Virulence factors from many pathogenic bacterial species are regulated in response to Fe2+. Experiments in which either additional 150 μM FeCl3 was added or available Fe2+ was removed (chelated using 100 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl) demonstrated there was no significant effect on transcription of yplA in response to Fe2+ concentration (data not shown).

Y. enterocolitica survives over a large pH range (pHs 4.0 to 10.0), which is certainly beneficial as it traverses the acidic stomach and is carried into the alkaline small intestine (5). Therefore, β-galactosidase activity was assayed in cultures grown in a series of buffered broth media (1% tryptone) inoculated in parallel. The effect of pH was examined using 1% tryptone broth containing a 50 mM concentration of the following buffers equilibrated at the indicated pH values: citric acid for pHs 5.0 and 6.0; HEPES for pHs 7.0 and 7.5, and TAPS [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid] for pHs 8.5 and 9.5. After 8 h of incubation, bacteria were harvested for β-galactosidase assays and the pH of the culture media was tested. In no case had the pH significantly changed (>0.2 pH U) from the original pH of the buffered media. In the pH range tested, pHs 5.0 to 9.5, the cultures reached similar cell densities (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 1.0 to 1.2), except for the most alkaline medium (pH 9.5; OD600, 0.5 to 0.7). These results suggest that yplA was efficiently transcribed at pHs 6 to 7.5 and expression peaked at pH 7.0 (Fig. 2C).

Given the identification of potential regulatory binding sites 5′ to the yplAB locus, environmental cues which affect the regulatory proteins were tested. First, the potential Fnr binding site upstream of yplX suggests that transcription of yplX, and perhaps yplA, might be regulated in response to oxygen tension. Few investigators have examined the response of Y. enterocolitica virulence gene expression at different oxygen levels: expression of both inv and ail is reduced under anaerobic conditions in vitro (inv is only significantly affected in rich medium at 26°C and not at 37°C or in minimal media) (36, 37). Therefore, the effect of aeration was determined using 5-ml cultures grown under the following conditions of increasing aeration, from least to greatest: in a culture tube on a wheel, in a slanted culture tube shaking at 250 rpm, and in a 125-ml flask shaking at 250 rpm. Static cultures were not included for comparison because these cultures grew slowly to a low cell density in 1% tryptone, which would not allow meaningful comparison of promoter activities. Vigorously shaken cultures produced a fifth of the β-galactosidase activity of cultures grown in tubes on a wheel (Fig. 3A). As maximum expression occurs when cell density is high and free oxygen is scavenged quickly, the oxygen tension in these culture is probably low. These results are consistent with Fnr-dependent regulation of yplA expression. Similar conditions of low oxygen tension occur in the gut lumen, so this condition may have relevance in the host (43).

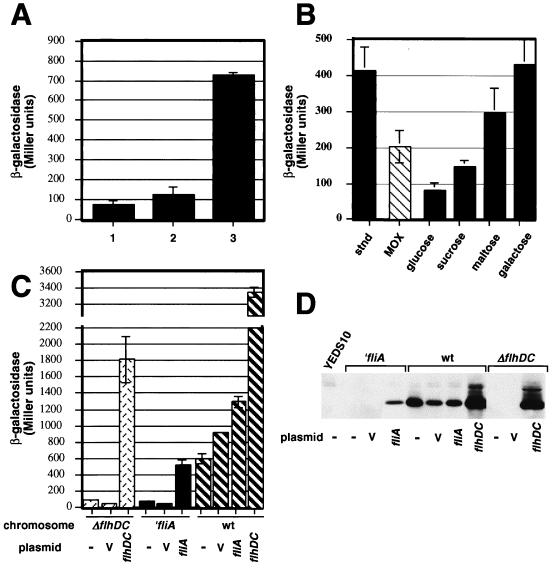

FIG. 3.

Effects of oxygen levels (A), added sugars (B), and flagellar regulators (C) on β-galactosidase activity production by Y. enterocolitica YEDS16 and Western analysis of Y. enterocolitica phospholipase production from YEDS16 and flagellar mutant Y. enterocolitica strains using anti-YplA serum (D). (A) Five-milliliter cultures of YEDS16 were grown in 1% tryptone broth at 26°C as follows: 1, in a 125-ml flask with vigorous aeration; 2, in a culture tube with vigorous aeration; 3, in a culture tube incubated on a wheel. (B) Cultures were grown under the standard conditions in 1% tryptone broth (black column) and with 20 mM added sugars (gray columns). One percent tryptone with 20 mM Mg oxalate (MOX) was included for comparison (striped column). (C) Effects of a flagellar regulator mutant background on production of β-galactosidase activity from yplA′::lacZY. Shown are results for the ′fliA mutant background, YEDS18−, with the pTM100 vector (v) and complemented with fliA on pJB222 (fliA) and the ΔflhDC mutant background, YEDS29 (−), with the vector pTM100 (v) and complemented with flhDC on pGY10 (flhDC) (dotted columns). Results for wild-type (wt) Y. enterocolitica YEDS16 and its derivatives carrying plasmids pTM100 (v), pJB222 (fliA), and pGY10 (flhDC) are shown as striped columns for comparison. (D) Proteins secreted into the medium were concentrated essentially as previously described (49), resuspended in reducing sample buffer, and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis essentially by the method of Laemmli (28). The polyacrylamide gels were transferred to nitrocellulose using a semidry transfer apparatus (Trans-Blot SD; Bio-Rad). The primary anti-MalE-YplA serum was used at 1/2,000, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G diluted to 1/30,000 (Sigma), and the Western immunoblot was developed by a chemiluminescence assay method (ECL; Amersham).

The identification of a cAMP-Crp binding site suggests that yplA is regulated by catabolite repression. For members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, the cAMP concentration varies inversely with the growth rate and the presence of glucose both reduces cAMP synthesis and stimulates its efflux from the cytoplasm (7, 40). Therefore, 20 mM glucose, sucrose, maltose, lactose, arabinose, galactose, or glycerol was added to 1% tryptone broth, the cultures were incubated under the standard conditions, and then levels of β-galactosidase activity were determined. The addition of 20 mM glucose or sucrose, a disaccharide of glucose and fructose, reduced the levels of β-galactosidase activity to a quarter and approximately a third of that observed in the 1% tryptone broth, respectively (Fig. 3B). Addition of other utilizable carbon sources at 20 mM, including maltose, galactose, arabinose, glycerol, and lactose, did not have a significant effect on the levels of yplA expression (Fig. 3B and data not shown). While lactose is a disaccharide composed of glucose and galactose, it had no significant effect on levels of β-galactosidase activity. This result is consistent with the fact that Y. enterocolitica is unable to utilize lactose as a carbon source. Furthermore, all of these results are consistent with the regulation of yplA by catabolite repression.

To confirm that the patterns of transcriptional regulation determined using the reporter fusion reflected the production of YplA protein, Y. enterocolitica grown under various conditions was examined by Western analysis using antiserum generated against YplA. Polyclonal antiserum was raised in a rabbit using MalE-YplA produced from pDHS28 in E. coli and purified as previously described (49). Confounding specificity for common bacterial antigens was removed by adsorption to acetone powders prepared from Y. enterocolitica YEDS10 (phospholipase null mutant) and E. coli containing pMal-p2 (20). In all cases, the amount of YplA detected correlated with the levels of expression determined using the yplA::lacZY fusion (data not shown).

yplAB expression requires the flagellar regulators (FlhDC and FliA).

The identification of a potential flagellar sigma factor-dependent promoter, export of YplA by the flagellar type III apparatus, and regulation of yplA and flagellar genes in response to temperature and ionic strength suggest that yplA is part of the flagellar regulon. This hypothesis was tested by introducing yplA::lacZY into Y. enterocolitica strains GY460 and JB400v, which have mutations in the flagellar regulatory genes flhDC (50) and fliA (2), respectively. The correct insertion of the reporter plasmid construct pDHS45 into ΔflhDC or ′fliA mutant strains was confirmed by Southern analysis (Fig. 1; data not shown). When bacteria were grown under standard conditions, β-galactosidase activity was reduced to ∼20% of wild-type levels in either YEDS29 (ΔflhDC) or YEDS18 (fliA) compared to YEDS16 (Fig. 3C). Parent strains JB400v and GY460 do not produce detectable phospholipase activity on plates. To confirm that the ΔflhDC or ′fliA mutation was responsible for the decreased β-galactosidase production, each mutation was complemented with the functional gene(s) carried on a plasmid, pGY10 (50) or pJB222 (2), respectively. For comparison, the plasmid vector pTM100 was introduced into the strains as well. The ′fliA mutation was complemented to wild-type levels of β-galactosidase activity by pJB222. Similarly, the ΔflhDC mutation was complemented by pGY10 yet it induced even greater β-galactosidase activity than that of the wild type, YEDS16 (Fig. 3C). In neither case did the pTM100 vector alone complement the mutation. To confirm that the patterns of transcriptional regulation determined using the reporter fusion reflected the production of YplA protein, Y. enterocolitica mutant strains with and without complementing plasmids were examined by Western analysis using antiserum generated against YplA. For all strains, the amount of YplA correlated with levels of lacZ expression (Fig. 3D). Thus, the results demonstrate that yplA is part of the flagellar regulon and are consistent with direct promotion of yplA transcription by FliA (ςF).

FliA-dependent regulation would provide a mechanism for both inhibition of yplA expression by ionic strength and temperature regulation of yplA. The flagellin genes fleABC are similarly repressed at 37°C and expressed at 26°C, and their expression is dependent on FliA (ςF) (23). In vitro, fliA expression is immediately arrested if the temperature is increased to 37°C, which explains the loss of motility and reduced expression of flagellin genes and yplA (24). Repression of yplA expression by ionic strength may also reflect its regulation as part of the flagellar regulon. Motility and flagellin production are also repressed by ionic strength, although the mechanism has not been elucidated (50). Thus far, characterization of the Y. enterocolitica flagellar regulatory cascade has determined that it is very similar to the E. coli and Salmonella paradigm (21, 30). The master regulator flhDC is required for expression of fliA, and FliA (ςF), in turn, promotes expression of the class III flagellar genes which complete the flagellum. Therefore, FlhDC is needed for expression of both class II and III genes but FliA is only necessary for expression of class III genes. Consequently, the effects of mutations in flhDC and fliA on expression are consistent with direct promotion of yplA transcription by ςF, possibly by binding to the identified ςF consensus site. With respect to the patterns of regulation by oxygen tension (Fnr), catabolite repression (cAMP-Crp), and a flagellar regulator (FliA), the behavior of yplA is identical to that of phlA of S. liquefaciens (16, 17). Indeed, the organization of the Y. enterocolitica yplXAB and S. liquefaciens orfXphlAB loci and the proteins encoded therein are very similar. Since both Serratia and Yersinia spp. are members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, it is certainly possible that other species have phospholipase genes at similar loci. The potential role of the PhlA phospholipase in pathogenesis has not been addressed, although S. liquefaciens is considered an opportunistic pathogen.

Based on the E. coli and Salmonella paradigm, flhDC is predicted to be under catabolite repression control; cAMP-Crp is required for flhDC transcription (21, 30). Interestingly, for Y. enterocolitica, the response to the addition of glucose differs for flagellin (and motility); with or without the addition of glucose, Y. enterocolitica is motile and similar levels of flagellin are produced (50). However, the phospholipase production appears to be catabolite repressed. This is consistent with the presence of a cAMP-Crp site upstream of yplA and suggests one mechanism to explain why yplA regulation does not always parallel the flagellar regulon. These data suggest that other regulatory mechanisms are superimposed on yplA expression, in addition to regulation by FliA and FlhDC.

Another consideration for the phospholipase is its secretion into the extracellular milieu, which is undoubtedly necessary for its role as a virulence factor. Indeed, a number of bacterial phospholipases have been identified as virulence factors, and without exception, they are all secreted proteins (reviewed in references 44 and 47). This Y. enterocolitica phospholipase has been shown to utilize the flagellar type III secretion apparatus (49). The expression of class II flagellar genes encoding this apparatus is dependent on FlhDC but does not require FliA or expression of the class III genes. Interestingly, the class II flagellar genes flhBAE of Y. enterocolitica are not transcriptionally regulated by temperature (14). As FlhA and FlhB are thought to be part of the secretion apparatus (1, 30), a functional flagellar type III secretion apparatus may be produced at 37°C although the flagellum is not complete and the yersiniae are not motile. Production of a functional flagellar secretion apparatus without a functioning flagellum might appear wasteful, unless the flagellar secretion apparatus serves another purpose, such as secretion of nonflagellar proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI27342 and AI01230 to V.L.M., AI09265 to D.H.S., and 5T AI0123 to G.M.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa S. Flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.344874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badger J. Ph.D. thesis. Los Angeles: University of California; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumler A J, Tsolis R M, van der Velden A W M, Stojiljkovik I, Anic A, Heffron F. Identification of a new iron regulated locus of Salmonella typhi. Gene. 1996;183:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker S, Holinghaus G, Gabrielczyk T, Unden G. O2 as the regulatory signal for FNR-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4515–4521. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4515-4521.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bercovier H, Mollaret H H. Yersinia. In: Krieg N, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borodovsky M, Rudd K E, Koonin E V. Intrinsic and extrinsic approaches for detecting genes in a bacterial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4756–4767. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botsford J L, Harman J G. Cyclic AMP in prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:100–122. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.100-122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bottone E J. Yersinia enterocolitica. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brubaker R R. Factors promoting acute and chronic disease caused by yersiniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:309–324. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis G, Laroche Y, Balligand G, Sory M-P, Wauters G. Y. enterocolitica, a primary model for bacterial invasiveness. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:64–87. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelis G, Vanooteghem J-C, Sluiters C. Transcription of the yop regulon from Y. enterocolitica requires trans-acting pYV and chromosomal genes. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:367–379. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Koning-Ward T F, Robins-Browne R M. Contribution of urease to acid tolerance in Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3790–3795. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3790-3795.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delor I, Cornelis G R. Role of Yersinia enterocolitica Yst toxin in experimental infection of young rabbits. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4269–4277. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4269-4277.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauconnier A, Allaoui A, Campos A, Van Elsen A, Cornelis G, Bollen A. Flagellar flhA, flhB, and flhE genes, organized in an operon, cluster upstream of the inv locus in Yersinia enterocolitica. Microbiology. 1997;143:3461–3471. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G G, FitzHugh W, Fields C A, Gocayne J D, Scott J D, Shirley R, Liu L I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Givskov M, Ebert L, Christiansen G, Benedik M J, Molin S. Induction of phospholipase- and flagellar synthesis in Serratia liquefaciens is controlled by expression of the flagellar master operon flhD. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Givskov M, Molin S. Expression of extracellular phospholipase from Serratia liquefaciens is growth-phase-dependent, catabolite-repressed and regulated by anaerobiosis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1363–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Givskov M, Molin S. Secretion of Serratia liquefaciens phospholipase from Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:229–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Givskov M, Olsen L, Molin S. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene for extracellular phospholipase A1 from Serratia liquefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5855–5862. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5855-5862.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helman J D. Alternative sigma factors and the regulation of flagellar gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2875–2882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iriarte M, Vanooteghem J C, Delor I, Diaz R, Knutton S, Cornelis G R. The Myf fibrillae of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapatral V, Minnich S A. Co-ordinate, temperature-sensitive regulation of the three Yersinia enterocolitica flagellin genes. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapatral V, Olson J W, Pepe J C, Miller V L, Minnich S A. Temperature-dependent regulation of Yersinia enterocolitica class III flagellar genes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1061–1071. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.452978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapperud G, Namork E, Skurnik M, Nesbakken T. Plasmid-mediated surface fibrillae of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica: relationship to the outer membrane protein YOP1 and possible importance for pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2247–2254. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2247-2254.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinder S A, Badger J L, Bryant G O, Pepe J C, Miller V L. Cloning of the YenI restriction endonuclease and methyltransferase from Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:8 and construction of a transformable R−M+ mutant. Gene. 1993;136:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90478-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolter R, Inuzuka M, Helinski D R. Transcomplementation-dependent replication of a low molecular weight origin fragment from plasmid R6K. Cell. 1978;15:1199–1208. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert de Rouvroit C, Sluiters C, Cornelis G R. Role of the transcriptional activator, VirF, and temperature in the expression of the pYV plasmid genes of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:395–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacNab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mekalanos J J. Duplication and amplification of toxin genes in Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 1983;35:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michiels T, Cornelis G R. Secretion of hybrid proteins by the Yersinia Yop export system. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1677–1685. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1677-1685.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikulskis A V, Delor I, Thi V H, Cornelis G R. Regulation of the Yersinia enterocolitica enterotoxin Yst gene. Influence of growth phase, temperature, osmolarity, pH and bacterial host factors. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:905–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pederson K J, Pierson D E. Ail expression in Yersinia enterocolitica is affected by oxygen tension. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4199–4201. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4199-4201.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pepe J C, Badger J L, Miller V L. Growth phase and low pH affect the thermal regulation of the Yersinia enterocolitica inv gene. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:123–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierson D E, Falkow S. The ail gene of Yersinia enterocolitica has a role in the ability of the organism to survive serum killing. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1846–1852. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1846-1852.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Portnoy D A, Moseley S L, Falkow S. Characterization of plasmids and plasmid-associated determinants of Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:775–792. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.775-782.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saier M H J, Feucht B U, McCaman M T. Regulation of intracellular adenosine cyclic 3′:5′-monophosphate levels in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7593–7601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmiel D H, Wagar E, Karamanou L, Weeks D, Miller V L. Phospholipase A of Yersinia enterocolitica contributes to pathogenesis in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3941–3951. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3941-3951.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sleisenger M H. Pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Songer J G. Bacterial phospholipases and their role in virulence. Trends Microbiol. 1997;156:156–161. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spiro S, Guest J R. Regulation and over-expression of the fnr gene of Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3279–3288. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-12-3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Titball R W. Bacterial phospholipases. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:127S–137S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner A F, Frey M, Neugebauer F A, Schafer W, Knappe J. The free radical in pyruvate formate-lyase is located on glycine-734. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:996–1000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young G M, Schmiel D H, Miller V L. A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6456–6461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young G M, Smith M, Minnich S A, Miller V L. The Yersinia enterocolitica motility master regulatory operon, flhDC, is required for flagellin production, swimming motility, and swarming motility. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2823–2833. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2823-2833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]