Abstract

With the deep application of automation and digitalization technologies, the global automobile value chains are undergoing a new round of large-scale restructuring, and the traditional supply chain structure taken vehicle manufacturers as the core has been broken. The dual-credit policy (DCP), taking over the subsidies for new energy vehicles (NEVs), plays a vital role in reconstructing, transforming, and upgrading the automobile industry. The target group of DCP is passenger vehicle manufacturers, but it is unclear how its implementation will affect the NEV industry chain. To address this issue, this study examined the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises using a DID (difference-in-difference) model based on the data of 693 listed advanced manufacturing enterprises in China A-shares from 2014 to 2021. The empirical results show that the DCP has significantly promoted the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. In terms of supply chain role heterogeneity, the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of parts manufacturers is more significant. Regarding enterprise ownership heterogeneity, the DCP has a greater impact on the innovation performance of SOEs(state-owned enterprises). In addition, regarding regional heterogeneity, enterprises in eastern and middle regions are significantly affected by the DCP to improve innovation performance.

Keywords: Dual-credit policy, Difference-in-differences model, New energy vehicle chain, Innovation performance, Industrial sustainability

1. Introduction

New energy vehicles (NEVs) are an essential engine of world economic growth and the measure to address the increasing scarcity of energy sources, embodying the strategy cross of carbon neutrality, energy security, and intelligent manufacturing [1]. As one of the world's largest automobile markets, China has provided strong policy support for the development of NEVs, including numerous technical standards, financial subsidies, tax breaks, and other regulatory policies, and China's NEV industry has made significant progress [2]. However, problems such as “subsidy fraud” and financial burdens have also emerged [3], [4]. To address these challenges, in 2017, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) issued the Measures for Parallel Management of Average Fuel Consumption and New Energy Vehicle Credits for Passenger Vehicle Enterprises (hereinafter referred to as the dual-credit policy (DCP)) [5] drawing on the CAFE(corporate average fuel economy) and ZEV(zero-emission vehicle) policy in the U.S. It aims to avoid a series of problems brought about by the rapid development of NEVs and, in anticipation of the withdrawal of the financial subsidies, to establish a coordinated development of energy efficiency and NEVs under the market-oriented mechanism [6].

Dual credit includes Corporate Average Fuel Consumption (CAFC) and NEV credits [5], [7]. Automakers are required to reduce CAFCs and increase NEV credits to avoid negative annual credits to ensure policy compliance [8], [4]. The implementation and continuous revision of the DCP pose a considerable challenge to automakers, who must innovate green to achieve technological advancement and green transformation [9]. Some scholars have already shown the innovation incentive effect of the DCP on vehicle manufacturing enterprises from the perspectives of supply chain management [9], [6] and empirical analysis [10], [11]. However, the innovation of NEVs is a highly complex systematic project that requires the collaborative innovation of the upstream and downstream enterprises in the NEV industry chain to be realized [12]. Then, does the policy effect of the DCP pass through the industrial chain and affect the innovation performance of new energy vehicle manufacturing enterprises (including parts and vehicle manufacturing enterprises)?

Prior academic research on the DCP has primarily concentrated on the two areas below: Macroeconomically, the focus is on the influence of the DCP on the automobile industry in China [13], [14], [15]; microscopically, most scholars investigate the optimal decisions of the automakers subjected to the influence of the DCP by game theory and optimization techniques [3], [16]. In recent years, DCP has received more and more attention in the study of the impact of DCP on technological innovation in the automobile industry. However, the conclusion for its effectiveness remains controversial. Some studies have shown that DCP can stimulate the technological innovation of NEVs. Zhou et al. [17] believed a positive relationship exists between DCP and manufacturers' green investment. By comparing the DCP and the subsidy policy, Li et al. [18] found that the DCP is more conducive to the technological innovation of NEVs. From the perspective of empirical analysis, scholars mainly use the DID model to study the impact of the DCP on innovation using a sample of Chinese A-share listed automobile enterprises from 2012 to 2020. Li et al. [10] argue that the DCP can improve the green innovation capability of automobile enterprises. He et al. [11] believe that the DCP significantly improves automakers' green technology innovation efficiency. Shi and Ming [19] show that DCP significantly incentivizes new energy automobile enterprises' substantive innovation behavior. Sun and Tian [20] found that since the introduction of the DCP in 2017, the quantity and quality of innovations by NEV enterprises have been significantly improved. He and Lin [21] believe that the DCP has significantly increased the probability, quantity, share, and quality of disruptive innovations in NEV enterprises.

Meanwhile, some other scholars have pointed out that the DCP needs further improvement. Lou et al. [8] argued that DCP may not aid manufacturers in enhancing the fuel economy of fuel vehicles or decreasing the production of high-fuel consumption vehicles. Cheng and Fan [4] believed that compared to setting a high NEV production ratio, maintaining a higher credit price is more favorable for increasing NEV production. Yang et al. [22] pointed out that automakers' performance would be negatively affected by the DCP, and a new R&D subsidy policy must be introduced at this stage. Meng et al. [23] showed that DCP can promote the development of the new energy vehicle industry, but capital constraints will weaken the incentive effect of the policy. Subsequently, Ma et al. [9], [24] have suggested that information asymmetry diminishes the incentive effect of the DCP. Yu et al. [6] argued that the current DCP makes it challenging for NEV manufacturers to innovate. The existing literature provides a solid theoretical foundation and modeling reference for our study. However, some limitations still exist. First, most of the existing literature ignores the impacts of the DCP on component manufacturers and fails to assess the impact of the DCP on both parts and vehicle manufacturers from a holistic perspective. Second, few studies have incorporated the vehicle industry reconstruction into the study of the DCP.

Therefore, this study aims to elucidate the mechanism of the effect of the DCP on the innovation performance of Chinese component and vehicle manufacturing enterprises. We treat the implementation of the DCP as a quasi-natural experiment and use China A-share advanced manufacturing enterprises as initial samples to investigate the mechanism of policy effects between 2014 and 2021 using a difference-in-difference (DID) model. The possible marginal contributions of our study are as follows: First, in contrast to previous studies [22], [10], [11] that only examined the impact of the DCP on the technological innovation of vehicle manufacturing enterprises, we explored the total impact of the DCP on parts and vehicle manufacturing enterprises in the context of industry restructuring. Second, regarding experimental sample selection, referring to Cao et al. [25], we take the advanced manufacturing enterprises covered by the ten critical areas as the initial research sample and identify the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. Third, we analyze the heterogeneity of the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of parts and vehicle manufacturers from the perspective of automotive industry restructuring, which contributes to the high-quality development of the automobile industry and the further optimization of DCP.

The remaining sections are organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework and hypotheses. Section 3 details the empirical model and data. Section 4 presents the empirical test and discussion. Section 5 provides conclusions and policy implications.

2. Theoretical framework and hypothesis proposed

2.1. New energy vehicle chain

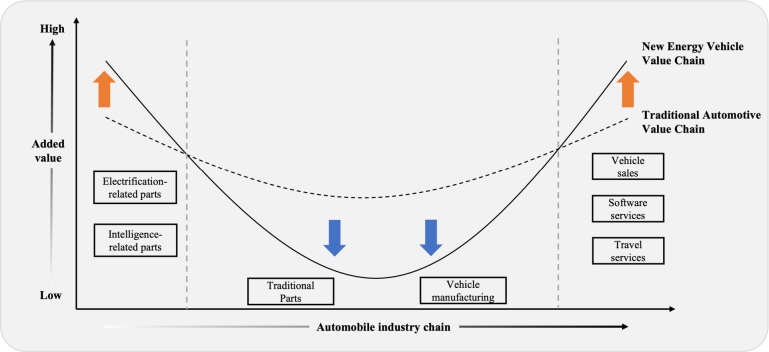

Long and extensive, the NEV chain is a complex ecosystem established by the interaction and cooperation between upstream and downstream enterprises. As depicted in Fig. 1,1 the complete NEV chain consists of four components: essential primary materials, core parts manufacturing, vehicle manufacturing, and the automobile aftermarket Parts and vehicle manufacturing enterprises are the heart of the entire automobile industry and the primary focus of our study.

Figure 1.

New energy vehicle chain. Source: Foresight Industry Research Institute.

Nowadays, the global automotive industry is undergoing an unprecedented transformation, including a shift from internal combustion engines to all-electric powertrains, a transition from distributed to centralized electronic and electrical architectures in vehicles, and an evolution from vertical integration to cross-industry collaboration in industrial division systems. This transformation accelerates the reconstruction of the NEV supply chain and value chain, which can be observed in four primary areas: The industry chain for powertrains forms around the battery, motor, and electronic control systems of NEVs. Software-defined vehicles and in-vehicle operating systems are now indispensable for automotive enterprises in achieving digital transformation. Furthermore, the adoption rate of advanced autonomous driving systems based on extensive data analysis is progressively increasing under the trend of intelligent and connected vehicles. Finally, the traditional supply system transforms as the automotive electronic and electrical architecture is upgraded.

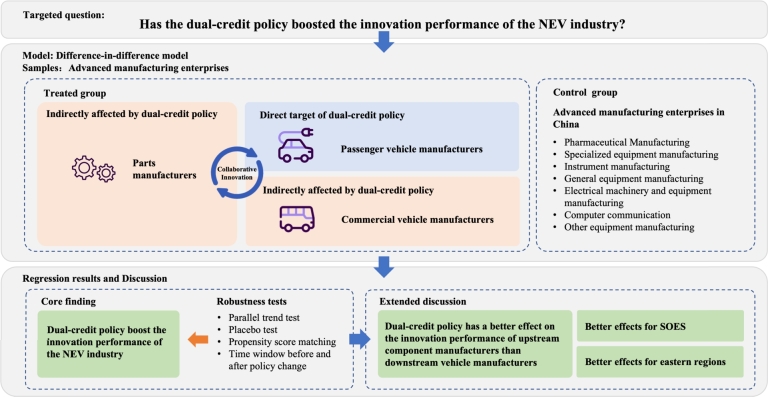

The reconstruction of the automotive industry chain has altered the existing value chain pattern and steepened the “smile curve” of the automotive industry chain (as depicted in Fig. 2).2 On the one hand, electrification, intelligent creation of incremental parts, and software-defined vehicles lead to modifications in profit models that increase the value added at both ends. On the other hand, the profit of traditional vehicle and component manufacturing has decreased, reducing the value added by intermediate connections. The formation of a new value chain signifies that the traditional “vehicle-parts” relationship with vehicle enterprises as the core is broken and that core parts enterprises gradually occupy an essential position in the “smile curve” of the industrial chain division of labor and take the lead in promoting the entire NEV industry's technological advancement and industrialization process.

Figure 2.

Smile curve of automobile value chain. Source: CICC Research Department.

In summary, from the perspective of the automotive industry reconstruction, parts manufacturers are the essential body of R&D and innovation of NEVs, and their position in the NEV industry is becoming more and more prominent. However, existing studies exploring the effects of the DCP have primarily focused on the impact on vehicle manufacturing enterprises [26], [22], [10], [11] while ignoring parts manufacturing enterprises. Therefore, our paper will explore the impact of DCP on NEV manufacturing enterprises (including parts and vehicle manufacturing enterprises) to fill the research gap.

2.2. Hypothesis proposed

2.2.1. The impact of DCP on innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises

DCP is a kind of industrial policy characterized by mandatory technological innovation, which is the gradual replacement and effective articulation of subsidy policy. It represents that China's automobile development policy has been changed from a subsidy-based incentive mechanism to a regulation-based mandatory orientation [6], [10], [26], and one of its important goals is to force automobile enterprises to green innovation and transformation and upgrading and to promote new energy automobile enterprises to circumvent the short-sighted effect of subsidy dependence, and to seek for a long-term development strategy based on technology [6].

In essence, DCP is an environmental regulatory policy. According to the Porter hypothesis [27], it can be seen that appropriate environmental regulation can stimulate enterprises to carry out more innovative activities, which in turn can increase enterprises' productivity, offset environmental protection costs, and improve enterprises' profitability [28]. Further, according to the weak Porter's hypothesis proposed by Jaffe and Palmercite [29], environmental regulation can incentivize enterprises to innovate in order to reduce the cost burden of environmental protection [30], [31]. DCP promotes the transition of vehicle manufacturers towards green and new energy vehicles by internalizing the external costs faced by vehicle manufacturers, thereby changing the relative rights of vehicle manufacturers and the government in the game [10]. Specifically, to ensure their policy compliance, vehicle manufacturing enterprises have the incentive to improve the fuel vehicles' fuel economy through green technological innovations and to develop NEVs further to earn positive NEV credits [8], [24], [6]. Meanwhile, the above analysis of the NEV chain reveals that NEV innovation is a complex process. DCP influences the modification of vehicle manufacturing enterprises' strategic planning directly, and further impacting the entire NEV chain system. Therefore, based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1

DCP is able to boost the innovation performance of both parts and vehicle manufacturing enterprises.

2.2.2. The impact of supply chain role on policy effect

Notably, in the process of NEV's transformation to electrification, intelligence, interconnection, and sharing, the technological innovation of the automobile industry is experiencing breakthroughs in multiple fields, triggering a new change in the chain of mutually supportive and synchronized technologies. In the current industrial change, the relationship between vehicle and parts enterprises has undergone qualitative changes. On the one hand, it is the reconstruction of the whole-zero relationship. With the continuous advancement of electric and hybrid vehicle technology, core component manufacturers, such as Ningde Times, Bosch, Continental, etc., have become more and more prominent in the supply chain. For example, the Bosch L9369 chip is a critical component of Bosch's Electronic Stabilization System (ESP), which Bosch supplies to 70% of domestic automakers.3 In 2022, Great Wall Motor's sales dropped by 20%, mainly due to the insufficient supply of Bosch's ESP chip.4 On the other hand, there is the reconstruction of the industrial value chain. New energy vehicles are reshaping the value chain of the traditional automobile industry. The profit structure of the industry has changed: the upstream power battery and intelligent electronic components and the downstream end-market user service may become a vital profit pool. For example, for the core powertrain components of the engine and transmission in traditional fuel vehicles, the cost accounted for about 30% of the vehicles. In contrast, for the battery, motor, and electronic control of new energy vehicles, the cost accounted for about 60%.5 It indicates that parts manufacturers provide the necessary technical support for vehicle manufacturers and play an essential role in promoting the technological progress of the entire industry [12], [9]. Therefore, based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

DCP has a greater impact on the innovation performance of parts manufacturing enterprises than vehicle manufacturing enterprises.

2.2.3. The impact of the nature of ownership on policy effect

The nature of ownership is the most basic institutional arrangement of the enterprise. Differences in enterprise ownership have an impact on the motivation for technological innovation and the acquisition and allocation of innovation resources, thus leading to the heterogeneity of technological innovation behaviors and effects of enterprises with different ownerships [32].

The nature of ownership is the most basic institutional arrangement of the enterprise. Differences in enterprise ownership impact the motivation for technological innovation and the acquisition and allocation of innovation resources, thus leading to the heterogeneity of technological innovation behaviors and effects of enterprises with different ownerships [32]. It will result in the heterogeneity of technological innovation behaviors and impacts on enterprises with different ownership [33]. There is no conclusive evidence on the impact of the nature of ownership on technological innovation. Some scholars believe that SOEs are weaker than non-SOEs in technological innovation due to the loss of incentives for technological innovation due to the constraints of business objectives and agency costs [20]. However, some scholars suggest that the incentive for technological innovation in non-SOEs is less significant than in SOEs [34], [19]. In the automobile industry, innovation is a systematic project involving multiple subjects and a lengthy cycle, requiring a high degree of synergy between multiple links, such as the level of industrial development, risk management, capital investment, and supporting facilities [35], [36], [12]. SOEs have chain-leader responsibility in the automobile industry chain in China; therefore, they should leverage their fundamental advantages in integrating innovation resources and providing continuous iteration and upgrading of new technologies, thereby promoting the deep integration of innovation in the NEV chain through resource integration and strategic leadership. Therefore, based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3

The nature of ownership affects the effect of DCP on the technological innovation of enterprises, and the policy effect is better in SOEs than in non-SOEs.

2.2.4. The impact of regional economic development level on policy effect

Schumpeter believed that technological innovation and economic growth are closely linked, and technological innovation is actually the process of economic growth [37]. Innovation capacity and efficiency are affected by the development status of regional industries and enterprises, the development level of the market economy, the composition of market subjects, and the distribution of factors [38]. Existing studies show an interactive relationship between technological innovation and regional economic development that promotes each other, and the improvement of the regional economic development level will be conducive to the role of innovation incentives [11], [20].

In addition, the agglomeration economic theory suggests that industrial agglomeration can improve productivity and innovation [39]. In regions with more advanced economic development, industrial clusters of automobiles and their components have often been formed. For example, many component suppliers have gathered around the Tesla Super Factory in Shanghai, including Ningde Times, Junsheng Electronics, Changying Precision, and others.6 In addition, innovative activities require a wealth of human resources and financial support [40]. Regions with a higher level of economic development usually have a better education system, a higher level of R&D institutions, and richer industry experience, and they can attract and train more highly skilled personnel. They also have more mature financial markets and richer sources of capital, which facilitates the provision of the financial support needed by enterprises for innovation. Therefore, based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4

Differences in regional economic development affect the effect of DCP on the technological innovation of enterprises, and the policy effect is better in economically developed regions than in economically underdeveloped regions.

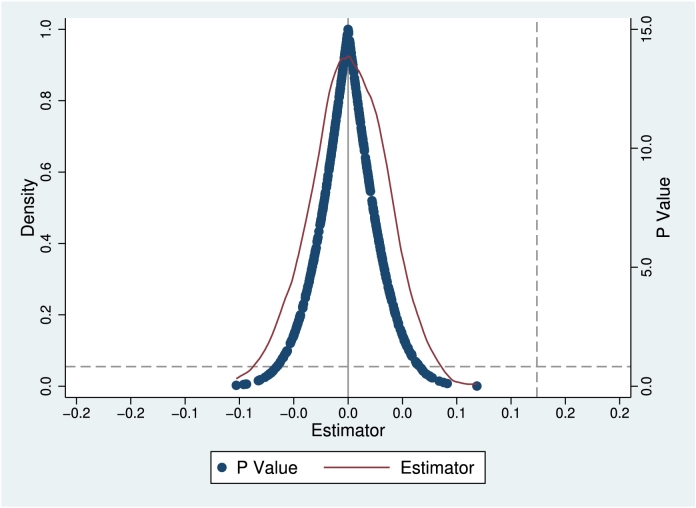

The research framework is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Research framework.

3. Model and data

3.1. DID model

We employ the DID model to evaluate the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises. The specific formulation of the baseline regression model is as follows:

| (1) |

Where represents the innovation performance of enterprise i in year t. is a dummy variable for grouping, 1 if the enterprise is affected by the DCP, 0 otherwise. is a dummy variable for the time of policy implementation, 1 for 2017 and later years, 0 otherwise. is the set of control variables, is the individual fixed effect, is the time fixed effect, and is the error term. This study focuses on the coefficient , which reflects the net effect of policy influence on the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises.

3.2. Data

3.2.1. Dependent variables

Referring to Li and Zheng [41] and Cao et al. [25], we measure the innovation performance of enterprises by the number of invention patent applications. This is due to the fact that (1) technological innovation is the value form of the transformation of the efficiency of enterprise resource input, allocation, and use. Invention patents as innovation output is the realistic embodiment of technological innovation in advanced manufacturing industries. (2) Invention patents are more in line with the characteristics of innovation and more demanding and better reflect the innovation capability of manufacturing industries.

3.2.2. Independent variables

(1) Whether it is an automobile manufacturing enterprise affected by the DCP (). We determine whether an enterprise is affected by the DCP based on official data from listed enterprises' official websites, announcements, and annual reports to determine whether the enterprise is involved in a certain part of the automobile manufacturing industry chain. If the enterprise is affected by the DCP, is 1; otherwise, it takes the value of 0.

(2) Whether the year is after the policy occurs (). We define 2014 to 2016 based on the fact that the MIIT released the DCP in September 2017 as the years that are not affected by the DCP, and 2017 to 2021 are defined as the years that are affected by the DCP, that is, is 1 for 2017 to 2021; otherwise, it is 0.

3.2.3. Control variables

We controlled the firm-level economic characteristic variables by referring to related studies on enterprise innovation [22], [10]. These characteristics can affect enterprises' innovation performance, including asset size (), capital structure (lev), current ratio (), return on total assets (ROA), R&D intensity (R&D), equity concentration (), and government subsidies () (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variable definition.

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| patentit | Number of patent applications, the natural logarithm of the annual number of patent applications for inventions plus 1. |

| treati | Dummy variable, 1 for enterprises affected by the DCP, 0 otherwise. |

| policyt | Dummy variable, 1 in the year of implementation of the DCP and in subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. |

| size | Asset size, the natural logarithm of total assets. |

| lev | Leverage, the ratio of total liabilities to total assets. |

| liquid | Current ratio, the ratio of current assets to current liabilities. |

| ROA | Return on total assets, the ratio of net income to total assets. |

| R&D | R&D intensity, the ratio of R&D investment to revenue |

| top10 | Shareholding concentration, top 10 shareholders' shareholdings |

| subsidy | Government subsidies, the natural logarithm of the government subsidies plus 1. |

3.3. Data source and processing

In our study, 2017 is taken as the time point when the DCP affects the innovation of automotive manufacturing enterprises. We select the advanced manufacturing enterprises listed in China A-shares from 2014 to 2021 as the initial research sample. Referring to previous relevant studies [41], [25], the data samples are censored, including the ST category, samples with missing data that cannot be filled, and delisted enterprises.

To implement Made in China 2025,7 guide the concentration of social resources, and promote the development of profitable and strategic industries, the Chinese Academy of Engineering has proposed the direction and path of innovation in ten key areas.8 Referring to Cao et al. [25], the advanced manufacturing enterprises covered by the above ten key regions are used as the initial research samples. Meanwhile, the advanced manufacturing enterprises that meet one of the following three cases are identified as automobile manufacturing enterprises affected by DCP (treatment group):

-

•

According to the Industry Classification Guidelines for Listed Enterprises (2012),9 enterprises belong to the automobile manufacturing industry.

-

•

According to their official websites, annual reports, and announcements, enterprises' actual business categories or main operating revenues include auto parts and components.

-

•

Enterprises' subsidiaries or branches have relevant auto parts and components products.

After the statistics, 178 enterprises were finally selected as the treatment group affected by DCP and 515 as the control group, with 5512 valid observations. In addition, to avoid the influence of outliers, a 1% tail shrinkage is applied to both the left and right ends of the data indicators. The financial data of the enterprises are obtained from WIND and CSMAR databases, the invention patent data come from the CNNDRS database, and whether the enterprises are involved in a specific part of the upstream and downstream of the automobile manufacturing chain is mainly based on official data from official websites, annual reports, and announcements.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results regression of DID model

Table 2 displays the regression results of the DCP on the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises. Column (1) displays the average impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises after controlling for industry, region, and year-fixed effects. The regression coefficient of DCP on innovation performance is 0.2381 (significant at the 1% level), indicating that DCP significantly improves the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. Column (2) adds control variables to column (1), and the regression results remain significant. Individual characteristics that do not vary over time are considered more thoroughly in columns (3) and (4), and the regression results of the fixed effects model (FE) are still significant after controlling for individual factors. From columns (1) to (4), it can be found that the regression coefficients focused on in our study are all significantly positive, which indicates that the implementation of the DCP has a significant role in promoting the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. Therefore, the results in Table 2 verify Hypothesis 1 to a certain extent, and we will subsequently launch a series of robustness tests.

Table 2.

Baseline regression results.

| Variable | OLS |

FE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (3) | |

| treat × policy | 0.2381*** | 0.0959** | 0.1387*** | 0.1562*** |

| (0.0571) | (0.0417) | (0.0443) | (0.0420) | |

| cons | 3.1716*** | -15.4771*** | 4.4210*** | -11.8552*** |

| (0.4620) | (0.4819) | (0.2853) | (0.8074) | |

| Control Variable | N | Y | N | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Area FE | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Industry FE | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Individual FE | N | N | Y | Y |

| N | 5,512 | 5,462 | 5,512 | 5,462 |

| R2 | 0.3238 | 0.6418 | 0.1265 | 0.2229 |

Note: ***, **, * respectively means the significance level are 1%, 5%, 10%. The values in brackets in Table 2 are t-value.

4.2. Parallel trend test

The DID model is used on the premise that the treatment and control groups satisfy the parallel trend hypothesis [42]. That is, prior to the implementation of the policy, there was no significant difference in the trend of the dependent variable between the treatment and control groups. Before the implementation of the DCP, there should be no discernible difference between the innovation performance of enterprises in the automobile manufacturing group and other advanced manufacturing groups. To examine the applicability of the DID model in this study, we draw on the methodology of Jacobson et al. [43] and utilize an event analysis research framework to evaluate the dynamic effects of the DCP. The following regression equation is estimated based on the model (1).

| (2) |

Where, the base year is the year of introduction of the DCP and is the dummy variable for the kth year of policy implementation. In addition, additional variables are consistent with those in the regression model (1).

Excluding 2016 to avoid total contribution, Fig. 4 reports the estimated results of the regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals. It can be found that none of the estimated coefficients for the years prior to the introduction of the DCP passes the significance test at the 5% level. This confirms that the treatment group (affected by the DCP) and the control group (not affected by the DCP) satisfy the parallel trend hypothesis. Therefore, the significant rise in the number of invention patent applications in the treatment group relative to the control group after 2017 results from the introduction of the DCP rather than a result of ex-ante differences.

Figure 4.

Dynamic effects of the DCP.

In addition, we observe a gradual increase in the impact of DCP on the innovation performance of NEV manufacturing enterprises, reaching statistical significance in 2021. However, there is a significant decrease in 2020. There are two main possible reasons for this. On the one hand, a series of problems in the implementation of the DCP, including the urgent need to update the technical standards, the lack of investment in fuel-efficient vehicle technologies, and the imbalance between supply and demand in the credit trading market [6]. On the other hand, Covid-19 has also had an impact on it. Against this background, the government made the first revision of the DCP [7] and formally implemented it in January 2021, which made the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of automobile manufacturers increases significantly in 2021, as shown in Fig. 4.

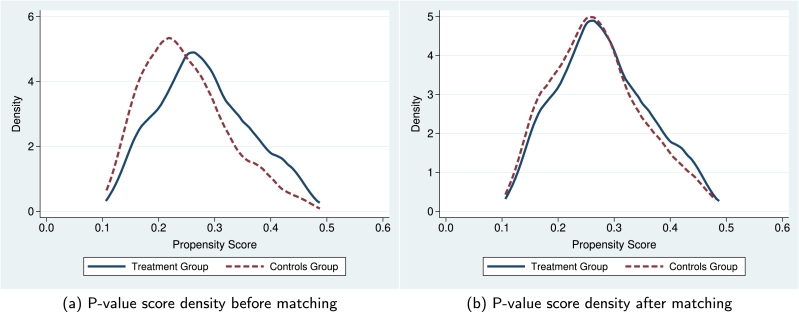

4.3. Placebo test

In this section, to rule out that the policy effect is affected by omitted variables, random factors, and others, referring to Chetty et al. [44] and La Ferrara et al. [45], we further test whether there are other unobservable factors affecting the result of the baseline regression by randomly selecting the years in which the DCP was implemented and the enterprises affected by the policy for a placebo test. In our study, 500 baseline regressions were repeated for random samples, and Fig. 5 illustrates the distribution of regression coefficients and corresponding p-values. The estimated coefficients of spurious regressions are centered around zero, and most estimated values have p-values more significant than 0.1, indicating that the omitted variables do not confound the policy effect of the DCP on automobile manufacturing enterprises and that the core results are still significant.

Figure 5.

Placebo test.

4.4. Robustness test

4.4.1. Propensity score matching

In this section, to avoid estimation bias due to sample selection bias, referring to Rosenbaum and Rubi [46], we use PSM-DID (propensity score matching - difference-in-differences) for robustness testing to further validate the causal relationship between the DCP and the improvement of China's manufacturing industry's innovation performance. Specifically, asset size (), capital structure (lev), current ratio (), return on assets (ROA), R&D intensity (R&D), equity concentration (), and government subsidies () were selected as characteristic variables and a Logit model was used to estimate the probability of inclusion for each sample. Then, the radius matching method was used to match a reasonable control group [30], [47]. Table 3 demonstrates that, after matching, standardized bias is significantly lower than 5% for all characteristic variables between the treatment and control groups, and none of the t-values after PSM are significant. It indicates that the matching results are valid.

Table 3.

Balance testing result of PSM.

| Variable | Unmatched Matched | Mean |

Bias (%) | Reduction in bias |

t-test |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | t | p > t | ||||

| size | U | 22.547 | 22.204 | 30.7 | 98.0 | 10.07 | 0.000 |

| M | 22.545 | 22.552 | -0.6 | -0.15 | 0.877 | ||

| lev | U | 0.4600 | 0.3906 | 38.1 | 98.2 | 12.29 | 0.000 |

| M | 0.4598 | 0.4611 | -0.7 | -0.18 | 0.855 | ||

| liquid | U | 2.0096 | 2.5066 | -28.8 | 96.4 | -8.64 | 0.000 |

| M | 2.0101 | 2.0281 | -1.0 | -0.31 | 0.754 | ||

| ROA | U | 2.9938 | 3.6544 | -10.6 | 97.6 | -3.32 | 0.001 |

| M | 2.9941 | 3.0097 | -0.3 | -0.07 | 0.946 | ||

| R&D | U | 0.0520 | 0.0576 | -15.0 | 80.5 | -4.58 | 0.000 |

| M | 0.0520 | 0.0531 | -2.9 | -0.80 | 0.421 | ||

| top10 | U | 0.5307 | 0.5362 | -4.0 | 99.9 | -1.28 | 0.201 |

| M | 0.5307 | 0.5307 | -0.0 | 0.00 | 0.999 | ||

| subsidy | U | 17.010 | 16.666 | 24.1 | 97.5 | 7.90 | 0.000 |

| M | 17.008 | 17.017 | -0.6 | -0.16 | 0.876 | ||

Fig. 6 (a) and (b) depict the P-value score kernel density of the treatment and control groups before and after matching, respectively. It can be seen that the matched control group is better able to make causal inferences than the treatment group's counterfactual outcome. Based on the matched samples, we construct PSM-DID to reassess the policy effects of the DCP. Table 4 displays the regression results, showing that the results are still significant after PSM.

Figure 6.

P-value score density.

Table 4.

Regression results based on PSM.

| Variable | OLS |

FE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (3) | |

| treat × policy | 0.2397*** | 0.0961** | 0.1375*** | 0.1551*** |

| (0.0571) | (0.0417) | (0.0443) | (0.0420) | |

| cons | 3.1697*** | -15.4667*** | 4.4199*** | -11.8623*** |

| (0.4618) | (0.4825) | (0.2853) | (0.8076) | |

| Control Variable | N | Y | N | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Area FE | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Industry FE | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Individual FE | N | N | Y | Y |

| N | 5,509 | 5,459 | 5,509 | 5,459 |

| R2 | 0.3242 | 0.6415 | 0.1268 | 0.2230 |

Note: ***, **, * respectively means the significance level are 1%, 5%, 10%. The values in brackets in Table 4 are t-values.

4.4.2. Time window before and after policy change

Based on the above analysis, we can conclude that the DCP significantly improves the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. However, the abovementioned regression analysis cannot reflect the magnitude and variability of the impacts in different time intervals before and after the DCP shock. Therefore, drawing on the methodology of Dong and Zhu [48], we alter the time window before and after the implementation of the DCP to investigate the impact gap on the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises. The regression results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of changing the policy time window.

| Variable | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year before and after | Two years before and after | Three years before and after | |

| treat × policy | 0.1243** | 0.1341*** | 0.1362*** |

| (0.0583) | (0.0497) | (0.0434) | |

| cons | -7.1156*** | -11.0425*** | -12.6340*** |

| (1.8088) | (1.0954) | (0.7937) | |

| Control Variable | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y |

| Area FE | N | N | N |

| Industry FE | N | N | N |

| Individual FE | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 2056 | 3426 | 4,782 |

| R2 | 0.0929 | 0.1435 | 0.2215 |

Note: ***, **, * respectively means the significance level are 1%, 5%, 10%. The values in brackets in Table 5 are t-values.

The results show that by changing the time window before and after the policy implementation, the policy effect does not change, and both significantly enhance the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises in the treatment group, indicating that the baseline regression result is robust. It can also be found that with the expansion of the time interval, the significance level of the dependent variable increases, and the estimated coefficients keep increasing, which indicates that the policy effect is persistent and can continue to promote the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises.

4.5. Heterogeneity analysis

4.5.1. Supply chain role

Based on the baseline regression, DCP has a significant positive impact on the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises. Further, it is worth exploring whether the DCP significantly impacts its target group (passenger vehicle manufacturing enterprises) more significantly than others (parts and business vehicle manufacturing enterprises) in the NEV industry chain. Therefore, two additional scenarios are examined: (1) passenger vehicle manufacturing enterprises as the treatment group and commercial vehicle manufacturing enterprises as the control group; (2) vehicle manufacturing enterprises as the treatment group and parts manufacturers as the control group, which have been conducted in other studies [26], [22], [10]. The results for these two scenarios are listed in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6. It can be found that the results are not significant, and interestingly, this is inconsistent with the finding revealed by Xiong et al. [26], Yang et al. [22], and Li et al. [10]. Combined with the baseline regression results, the DDC can effectively improve the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises. However, the policy effect is similar for enterprises within the automobile manufacturing industry. Obviously, although the DCP works directly on passenger vehicle manufacturing enterprises, its policy effects have apparent spillover effects in the NEV supply chain.

Table 6.

Policy effects at different locations in the chain.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| treat × policy | 0.0447 | -0.0033 | 0.1362*** | 0.0859* | 0.0903* |

| (0.2858) | (0.1545) | (0.0433) | (0.0475) | (0.0470) | |

| cons | -26.2877*** | -25.8256*** | -12.6368*** | -12.4538*** | -12.0156*** |

| (7.7598) | (3.4339) | (0.7143) | (0.7316) | (0.7267) | |

| Control Variable | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 149 | 524 | 5,310 | 5,005 | 5,014 |

| R2 | 0.4712 | 0.3516 | 0.2230 | 0.2161 | 0.2121 |

Note: ***, **, * respectively means the significance level are 1%, 5%, 10%. The values in brackets in Table 6 are t-values.

Further, we delve into the degree of positive incentives of the DCP for each part of the NEV supply chain compared with other advanced manufacturing enterprises. To this end, we add dummy variables to the baseline model to represent the position of enterprises in the NEV supply chain and obtain three sub-samples of parts manufacturing enterprises, passenger vehicle manufacturing enterprises, and commercial vehicle manufacturing enterprises for group regression. The estimates for the sub-samples of parts manufacturing enterprises, passenger vehicle manufacturing enterprises, and commercial vehicle manufacturing enterprises are presented in columns (3), (4), and (5) of Table 6. The findings indicate that the treatment effects are consistent across the three sub-samples. At 13.62%, 8.59%, and 9.03%, respectively, the DCP has a significant innovation-promoting effect on both upstream and downstream enterprises in the NEV supply chain. Compared to upstream vehicle manufacturing enterprises, DCP is more effective in positively incentivizing parts manufacturing enterprises' innovation performance. This conclusion has also been confirmed by latest research in the NEV supply chain decision-making [24], [9].

The heterogeneous effects described above are attributed to the following reasons: In the current restructuring of the automotive industry, the status of component manufacturers has been significantly elevated. This shift is largely driven by rapid advancements in technology and changing market demands, particularly the increasing adoption of NEVs. Parts manufacturers, traditionally in a supportive role, are now pivotal in driving innovation across the industry. Their enhanced status comes from their critical role in developing advanced technologies such as high-efficiency batteries, electric motors, and sophisticated electronic control systems. These components are essential for meeting the stringent standards set by the DCP, which not only assess vehicle manufacturers but also place implicit demands on the supply chain to innovate and reduce emissions. The evolving role of these manufacturers reflects a deeper integration into the core strategic objectives of the entire automotive sector, making them key players in the industry's transition towards sustainability. In addition, Commercial vehicle manufacturing enterprises are also innovating in response to industry upgrades and the shifting paradigms of automotive manufacturing, driven by the need to stay competitive in a rapidly changing market environment where customers increasingly value efficiency and sustainability.

Through inventive “vehicle-parts” partnerships, parts manufacturing enterprises and vehicle manufacturing enterprises promote the integrated development of the industry in light of the current new circumstances and trend development in the automobile industry. CAFC requires the reduction of fuel consumption of conventional fuel vehicles, which necessitates technological advancements in engines, transmissions, and other components; NEV credits necessitate the development of electric motors, power batteries, and electronic controls. Even though the DCP is a direct evaluation of the vehicle manufacturing enterprises, its technological advancement is driven by the component manufacturing enterprises. Consequently, businesses that manufacture upstream components are the most responsive to the DCP. First, the majority of commercial vehicle manufacturing enterprises have models that are directly affected by the double-points policy; second, the introduction of the DCP prompts some forward-thinking enterprises to recognize the need to vigorously develop energy-saving and new energy commercial vehicles, advance the layout, and enhance the innovation of production, energy saving, and emission reduction.

4.5.2. Enterprise ownership

In this subsection, the entire sample is divided into two categories, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (Non-SOEs), to test the effect of ownership heterogeneity of the DCP on the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises. The regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7. It can be found that the coefficients of the impact of the DCP on enterprises' innovation performance are all significantly positive. Moreover, regarding the estimated coefficients' size, the incentive effect of the DCP on innovation is more significant for SOEs than Non-SOEs.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity test.

| Variable | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise ownership |

Regional economic development level |

||||

| SOE | Non-SOE | Eastern region | Middle region | Western region | |

| treat × policy | 0.1580** | 0.1324** | 0.1320*** | 0.2189** | 0.0728 |

| (0.0702) | (0.0523) | (0.0488) | (0.1006) | (0.1452) | |

| cons | -9.6613*** | -13.6230*** | -11.3316*** | -14.4174*** | -19.2816*** |

| (1.3498) | (0.8512) | (0.8174) | (1.9841) | (2.3398) | |

| Control Variable | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Individual FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | 1,755 | 3,704 | 3,879 | 1,060 | 520 |

| R2 | 0.2457 | 0.2232 | 0.2165 | 0.2631 | 0.2921 |

Note: ***, **, * respectively means the significance level are 1%, 5%, 10%. The values in brackets in Table 7 are t-values.

The aforementioned heterogeneous effect can be attributed to the subsequent causes. (1) China's innovation-driven development strategy has given SOEs the mission and task they deserve. At present, China's large state-owned automobile manufacturing enterprises occupy a core dominant position in the industrial chain and have the primary advantage of leading the development in terms of capital, technology, talents, and other innovation factors, and can play a driving and pulling role, pulling the upstream and downstream of the automobile industrial chain to synergize the development and technological progress. (2) Since the comprehensive deepening of the reform of SOEs, Chinese automobile SOEs' competitiveness, innovation, influence, and risk-resistant ability have been substantially enhanced. As a result, they can respond more positively and quickly to the DCP so that the external policy can be more fully transformed into the endogenous impetus of technological innovation. (3) From the history of China's automobile industry development, almost only state-owned enterprises with sufficient capital and development history have the ability to carry out the production of automobiles. As a strategic emerging industry in China, NEV has high requirements for enterprises' scale and innovation ability. Non-SOEs are in the process of market competition, transformation, and upgrading of financing constraints and resource factors, such as the shortage of shackles, to a certain extent, to limit their innovation and development in the automotive industry. Therefore, the DCP has a more significant effect on the innovation incentive of SOEs.

4.5.3. Regional economic development level

China is a vast country, and there are differences in the industrial system and economic development level of different regions. Based on the model (1), we introduce regional dummy variables and divide the whole sample into three categories, namely, eastern, middle, and western regions, according to the economic zone classification method of the National Bureau of Statistics, to analyze regional heterogeneity. The estimated values of the subsamples from the eastern, middle, and western regions are presented in columns (3), (4), and (5), respectively, of Table 7. It can be found that the estimated coefficients are all significant at the 1% significance level for the eastern region, at the 5% significance level for the middle region, and not significant for the western region. It indicates that the DCP enhances the innovation performance of automobile manufacturing enterprises in the eastern and middle regions.

The above heterogeneous effects can be attributed to the following reasons: (1) The western region is constrained by factors such as geographic location, natural elements, and development foundation, with scarce innovation resources and weak innovation capacity. (2) The central region has the location advantage of carrying the east to the west and connecting the south to the north, as well as rich resource elements, huge market potential, and profound cultural heritage. Benefit from the strategy of the rise of the central region in recent years,10 the central region will accelerate the rise of China's development map to support the “spine” for high-quality development and the construction of Chinese-style modernization to create essential strategic support. (3) The eastern region benefits from its favorable geographical location and open-door policy, and its economic development is faster. The accumulation of long-term capital makes its regional resource agglomeration and social innovation atmosphere better than other regions, which is more conducive to the technological innovation activities of enterprises. In summary, the impact of DCP on enterprises' innovation performance is characterized by significant regional heterogeneity.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

5.1. Conclusions

This paper uses the data of 693 China A-share listed enterprises in the advanced manufacturing industry from 2014 to 2021 as the initial research sample. It divides the initial research sample into treatment and control groups based on the criterion of whether or not they are involved in the automobile manufacturing industry. Taking the implementation of the DCP as a quasi-natural experiment, we utilize a DID model to explore the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of China's automobile manufacturing enterprises. The empirical result shows that the DCP significantly improves the innovation performance of Chinese automobile manufacturing enterprises, and the above finding remains significant after a series of tests, such as propensity score matching and changing the time window period. In terms of supply chain role heterogeneity, the impact of the DCP on the innovation performance of parts manufacturers is more significant. Regarding enterprise ownership heterogeneity, the DCP has a greater impact on the innovation performance of SOEs. In addition, regarding regional heterogeneity, enterprises in eastern and middle regions are significantly affected by the DCP to improve innovation performance.

5.2. Implications

The policy implications are proposed as follows.

-

•

Continue to improve and adjust the DCP to further stimulate the innovation power of automakers. On the one hand, the government should improve the market mechanism of credit transactions. Currently, the market mechanism of DCP is still unsound, and it is difficult to fully digest the positive credits, resulting in the problem of surplus credits, which affects the willingness of vehicle manufacturing enterprises to innovate. On the other hand, the technical threshold of NEVs should be raised. The government should continuously update the standard according to the status quo of industrial development and technological progress to avoid weakening enterprises' innovation power due to surplus credits.

-

•

Expand the scope of application of the DCP. The government should actively promote commercial vehicle credit management. China's commercial vehicle holdings account for only 12% of the overall automobile, while carbon emissions account for more than 55%. Compared with passenger vehicles, the carbon reduction of commercial vehicles is even more urgent.

-

•

The government should further consider ownership differences when formulating policies. Considering the high technological content of NEVs and the high risk of research and development, the government can further provide innovation financing, tax incentives, and other policy support for non-SOEs to reduce technological innovation risks and stimulate innovation vitality.

-

•

The government should further consider regional differences when formulating policies. For economically underdeveloped middle and western regions, local governments should formulate more targeted and detailed NEV industry policies based on the central government's policies, provide corresponding policy guidance and support to local enterprises, and help local enterprises carry out high-quality innovation. Especially for small and medium-sized enterprises, the government should focus on helping them open up market channels, enjoy policy dividends, and increase their willingness to innovate.

In addition, our study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of the DCP in promoting innovation within the automotive industry. These insights can be instrumental for policymakers in other countries considering similar regulatory frameworks. Specifically:

-

•

Adaptability of policy mechanisms: The DCP's core mechanism — using credits and penalties to drive industry behavior — demonstrates a flexible approach that could be adapted to different regulatory environments to encourage innovation in the automotive sector.

-

•

Insights into policy spillovers: The study shows that the DCP had broad spillover effects across the entire NEV supply chain, suggesting that similar policies in other countries could also foster comprehensive industrial benefits, not just targeted improvements.

-

•

Guidance on implementation: Our analysis reveals which aspects of the DCP were most effective, such as its impact on parts manufacturers. This can guide other nations in designing incentives that specifically target crucial segments of their automotive industries to stimulate innovation and technological upgrades.

5.3. Future studies

Finally, this study has some shortcomings and limitations that need to be addressed in future research. (1) The DCP has been revised twice, and the effect of the policy revision can be further analyzed after the policy has been implemented for a more extended period. (2) How to measure the level of technological innovation of enterprises more comprehensively is still to be further researched, and we can consider establishing a comprehensive index system that includes patents, technological innovation efficiency, R&D investment, and other indicators, to comprehensively evaluate the level of technological innovation of enterprises.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hui Yu: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Ying Li: Project administration. Wei Wang: Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72074076).

Data availability

Some or all the data, models, or codes generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Li Jingjing, Jiao Jianling, Xu Yuwen, Chen Chuxi. Impact of the latent topics of policy documents on the promotion of new energy vehicles: empirical evidence from Chinese cities. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021;28:637–647. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma Shao-Chao, Xu Jin-Hua, Fan Ying. Willingness to pay and preferences for alternative incentives to ev purchase subsidies: an empirical study in China. Energy Econ. 2019;81:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Haicheng, Lou Gaoxiang, Fan Tijun, Chan Hing Kai, Chung Sai Ho. Conventional Automotive Supply Chains Under China's Dual-Credit Policy: Fuel Economy, Production and Coordination. Energy Policy. April 2021;151 Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Yongwei, Fan Tijun. vol. 103. Publisher: Pergamon; September 2021. Production Coopetition Strategies for an Fv Automaker and a Competitive Nev Automaker Under the Dual-Credit Policy; p. 102391. (Omega). [Google Scholar]

- 5.MIIT Measures for parallel administration of average fuel consumption and new energy vehicle credits of passenger vehicle enterprises. 2017. https://wap.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/zbys/qcgy/art/2020/art_f09be90b302f4875928ac1c05a5c3bbc.html

- 6.Yu Hui, Li Ying, Wang Wei. Optimal innovation strategies of automakers with market competition under the dual-credit policy. Energy. July 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 7.MIIT Decision on amending the measures for parallel administration of average fuel consumption and new energy vehicle credits of passenger vehicle enterprises. 2020. https://wap.miit.gov.cn/gyhxxhb/jgsj/cyzcyfgs/bmgz/qtl/art/2020/art_4dd5db1cc927478e94764ce903fe8718.html

- 8.Lou Gaoxiang, Ma Haicheng, Fan Tijun, Chan Hing Kai. Impact of the Dual-Credit Policy on Improvements in Fuel Economy and the Production of Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. May 2020;156 Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Miaomiao, Meng Weidong, Li Yuyu, Huang Bo. Impact of dual credit policy on new energy vehicles technology innovation with information asymmetry. Appl. Energy. February 2023;332 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Bo, Chen Yiran, Cao Shaopeng. Carrot and stick: does dual-credit policy promote green innovation in auto firms? J. Clean. Prod. June 2023;403 [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Haonan, Li Shiqiang, Wang Shanyong, Zhang Chaojia, Ma Fei. Value of dual-credit policy: evidence from green technology innovation efficiency. Transp. Policy. 2023;139:182–198. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han Jing, Guo Ju-E., Cai Xun, Lv Cheng, Lev Benjamin. An analysis on strategy evolution of research & development in cooperative innovation network of new energy vehicle within policy transition period. Omega. October 2022;112 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou Shiqi, Lin Zhenhong, Qi Liang, Li Jie, He Xin, Przesmitzki Steven. The dual-credit policy: quantifying the policy impact on plug-in electric vehicle sales and industry profits in China. Energy Policy. 2018;121:597–610. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Sinan, Zhao Fuquan, Liu Zongwei, Hao Han. Impacts of a super credit policy on electric vehicle penetration and compliance with China's corporate average fuel consumption regulation. Energy. 2018;155:746–762. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Yaoming, Zhang Qi, Tang Yanyan, Mclellan Benjamin, Ye Huiying, Shimoda Hiroshi, Ishihara Keiichi. Dynamic optimization management of the dual-credit policy for passenger vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;249 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Yongwei, Fan Tijun, Zhou Li. Optimal strategies of automakers with demand and credit price disruptions under the dual-credit policy. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2022;7(3):453–472. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Dequn, Yu Yi, Wang Qunwei, Zha Donglan. Effects of a generalized dual-credit system on green technology investments and pricing decisions in a supply chain. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;247:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Jizi, Ku Yaoyao, Liu Chunling, Zhou Yuping. Dual credit policy: promoting new energy vehicles with battery recycling in a competitive environment? J. Clean. Prod. 2020;243 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Dan, Ming Xing. Can the “dual-credit” policy promote substantive innovation of new energy vehicles. J. Beijing Inst. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023;25(04):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Jianguo, Tian Mingfu. Did the dual-credit policy promote the “quality and quantity” of innovation in new energy vehicle enterprises? Soft Sci. 2023 http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/51.1268.G3.20230906.0923.002.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Yubing, Lin Ting. The impact mechanisms of compulsory institutional pressureon disruptive innovation: an empirical study on the cafc & nevc redit regulation of China's new energy vehicle industry. 2024. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1224.G3.20240322.1548.012.html (in Chinese) Science & Teechnology Progress and Policy.

- 22.Yang D.-X., Meng J., Yang L., Nie P.-Y., Wu Q.-G. Dual-credit policy of new energy automobile at China: inhibiting scale or intermediary of innovation? Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022;43 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng Weidong, Ma Miaomiao, Li Yuyu, Huang Bo. New energy vehicle R&d strategy with supplier capital constraints under China's dual credit policy. Energy Policy. September 2022;168:113099. Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Miaomiao, Meng Weidong, Huang Bo, Li Yuyu. The influence of dual credit policy on new energy vehicle technology innovation under demand forecast information asymmetry. Energy. May 2023;271 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Hongjian, Zhao Yu, Li Jiao. Does the “belt and road” initiative enhance the innovation capability of China's advanced manufacturing industry. Word Econ. Stud. 2021;326(04):104–119. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Xu, Xiong Yongqing. Research on the influence of the cafc-nev mandate on R&D investment of new energy vehicle manufacturers. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2021;39(10):1770–1780. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter Michael E., van der Linde Claas. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. December 1995;9(4):97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Chunhua, Jiang Dequan, Lan Meng, Li Weiping, Ye Ling. Does environmental regulation affect labor investment efficiency? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. July 2022;80:82–95. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe Adam B., Palmer Karen. Environmental regulation and innovation: a panel data study. Rev. Econ. Stat. November 1997;79(4):610–619. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du Gang, Yu Meng, Sun Chuanwang, Han Zhao. Green innovation effect of emission trading policy on pilot areas and neighboring areas: an analysis based on the spatial econometric model. Energy Policy. September 2021;156 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Yigang, Zhu Rongqi, Tan Longyan. Emission trading scheme, technological innovation, and competitiveness: evidence from China's thermal power enterprises. J. Environ. Manag. October 2022;320 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Xianjun, Wang Wei, Liu Wenchao, Jinglun Wang. Research on the relationship among ownership attribution, innovation input and firm performance of listed auto companies in China. Manag. Rev. 2018;30(02):71–82. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clò Stefano, Florio Massimo, Rentocchini Francesco. Firm ownership, quality of government and innovation: evidence from patenting in the telecommunication industry. Res. Policy. June 2020;49(5) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Liuyong, Zhang Zeye. The impact of green credit policy on corporate green innovation. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022;40(02):345–356. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller Roger. Global R & D networks and large-scale innovations: the case of the automobile industry. Res. Policy. January 1994;23(1):27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sierzchula William, Bakker Sjoerd, Maat Kees, van Wee Bert. Technological diversity of emerging eco-innovations: a case study of the automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. December 2012;37:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumpeter Joseph A., Swedberg Richard. Routledge; 2021. The Theory of Economic Development. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez-Pose Andrés, Crescenzi Riccardo. Research and development, spillovers, innovation systems, and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Reg. Stud. February 2008;42(1):51–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Hui, Shen Neng, Ying Huanqin, Wang Qunwei. Can environmental regulation directly promote green innovation behavior?—— based on situation of industrial agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;314 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Changjin, Qi Huarui, Jia Lijun, Wang Yanjiao, Huang Dan. Impact of digital technologies and financial development on green growth: role of mineral resources, institutional quality, and human development in south Asia. Resour. Policy. 2024;90 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Wenjing, Zheng Manni. Is it substantive innovation or strategic innovation? —Impact of macroeconomic policies on micro-enterprises' innovation. Econ. Res. J. 2016;51(4):60–73. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertrand Marianne, Duflo Esther, Mullainathan Sendhil. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates?*. Q. J. Econ. February 2004;119(1):249–275. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobson Louis S., LaLonde Robert J., Sullivan Daniel G. Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993;83(4):685–709. Publisher: American Economic Association. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chetty Raj, Looney Adam, Kroft Kory. Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. September 2009;99(4):1145–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 45.La Ferrara Eliana, Chong Alberto, Duryea Suzanne. Soap operas and fertility: evidence from Brazil. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. July 2012;4(4):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenbaum Paul R., Rubin Donald B. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am. Stat. February 1985;39(1):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao De, Yu Fan, Guo Chenhao. The impact of China's pilot carbon ETS on the labor income share: based on an empirical method of combining PSM with staggered DID. Energy Econ. August 2023;124 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong Yanmei, Zhu Yingming. Can high-speed rail construction reshape the layout of China's economic space-based on the perspective of regional heterogeneity of employment, wage and economic growth. China Ind. Econ. 2016;10:92–108. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all the data, models, or codes generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.