Abstract

Objectives

The most common cause of lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) in cats under the age of 10 years is feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC). The prevalence of LUTS in the UK pet cat population is difficult to assess. This study used data collected prospectively to investigate the prevalence of, and risk factors for, owner-reported LUTS in a cohort of young pet cats.

Methods

Cat owners were recruited into a long-term longitudinal study and asked to complete questionnaires at specified age points for their cats. All cats were at least 18 months of age at the time of analysis. The prevalence of owner-reported LUTS at 18, 30 and 48 months of age was calculated, based on whether the owner had seen the cat urinating, and whether the cat had displayed one or more of the following clinical signs: dysuria, haematuria or vocalising during urination. A case-control study to investigate the risk factors for owner-reported LUTS in study cats at age 18 months was also conducted, using a multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

The prevalence of owner-reported LUTS in cats seen urinating by the owner was 4.3%, 3.8% and 6.0%, with 95% confidence intervals of 3.2–5.7%, 2.5–5.7% and 3.4–10.5% at ages 18, 30 and 48 months, respectively. An indoor-only lifestyle at the age of 18 months and a change in diet between the ages of 12 and 18 months were identified as risk factors for owner-reported LUTS at the age of 18 months from the multivariable model. No clear type of change in diet was identified in our sample of cats with LUTS.

Conclusions and relevance

The prevalence of owner-reported LUTS in a cohort of young pet cats was higher than the previously reported prevalence of LUTS in cats presenting to veterinary hospitals for LUTS or other reasons. A novel risk factor of change in diet between 12 and 18 months of age warrants further investigation.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) in cats include stranguria, periuria, haematuria, dysuria and pollakiuria.1,2

The prevalence of LUTS in the pet cat population in the UK is difficult to assess; the most recent estimates for the prevalence in the general population in both the UK and USA were 0.6%, but these were based on data from the mid-1970s. 3 In 1999, Lund et al reported LUTS in 3% (1.5% ‘feline urological syndrome’ and 1.5% ‘cystitis’) of cats examined at private veterinary practices in the USA. 4 More recently, the Banfield State of Pet Health reported that ‘cystitis’ (LUTS) accounted for approximately 5% of diagnoses in cats older than 3 years of age presented for care of a health problem. 5

The most common cause of LUTS in cats under the age of 10 years is feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC). Studies over the past 25 years have found that the majority (55–73%) of cats presented to referral hospitals in USA and Europe for LUTS had FIC.6–14 To our knowledge, the majority of studies of the prevalence of FIC have been based on data collected from cats that have presented to a veterinary surgeon (either primary care or referral hospital) because of LUTS. There are no data on the length of time that LUTS signs were present in the cats before the first presentation to the veterinarian. FIC can resolve without medical treatment or intervention, so LUTS may resolve in some cats before they would be presented to a veterinarian for treatment. Therefore, the actual prevalence of LUTS in cats could be higher than is currently reported. LUTS can occur at any age, but are seen most commonly in middle-aged cats.1,15 The age of onset of LUTS in cats could be younger than is currently reported. Cats could show signs at an earlier age, but owners might only take the cat to a veterinarian once the signs increase in frequency, or become severe or inconvenient (eg, periuria).

Factors previously associated with an increased risk of developing FIC include age (young adult cats at higher risk), being neutered, low activity levels, higher body condition score (BCS), limited outdoor access, stress factors such as moving house within the last 3 months, presence of more than one cat in the house, being in conflict with another cat in the house and a predominantly ‘dry’ diet.1,16–18 Moreover, to our knowledge, all of the information published to date on LUTS in cats has been based on data obtained retrospectively. Retrospective data collection has the potential for bias associated with recall and case-control status.

The aims of this study were to use prospectively collected data to investigate the prevalence of, and risk factors for, owner-reported LUTS in a cohort of young pet cats.

We used three owner-reported LUTS (straining and vocalising when passing urine, and haematuria) to create a binary outcome of ‘LUTS’ to estimate the prevalence of LUTS in cats at 18, 30 and 48 months of age. Risk factors for LUTS at 18 months were also investigated.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Cat owners were recruited into a long-term longitudinal study (Bristol Cats Study) using a variety of advertising methods, including posters in veterinary practices, advertisements through websites used by cat owners, animal welfare organisations, and publications aimed at veterinarians and cat owners. Cats included in this study were recruited between 1 May 2010 and 31 December 2013. Owners were asked to complete questionnaires either online or using a paper format when their cats were approximately 3 months (range 2–4 months) (questionnaire 1 [3 months]), 7 months (questionnaire 2 [7 months]), 12 months (questionnaire 3 [12 months]), 18 months (questionnaire 4 [18 months]), 30 months (questionnaire 5 [30 months]) and 48 months of age (questionnaire 6 [48 months]). Most questions were ‘closed questions’ with a multiple-choice format, and questionnaires took approximately 10–15 mins to complete. Questionnaires were developed by researchers with specialisms in feline medicine, veterinary epidemiology and feline behaviour, and data from respondents were anonymised prior to analysis. Links to electronic versions of questionnaires 1–4 (Q1–Q4), which were used for this study, are available at: https://smvsfa.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/bristol-cats-study-questionnaire-1-kitten-aged-8-16-wks-2 (Q1), https://smvsfa.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/bristol-cats-study-questionnaire-2-6-month-old-cats-c (Q2), https://smvsfa.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/bristol-cats-study-questionnaire-3-12-month-old-cats-c (Q3) and https://smvsfa.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/q4bc (Q4). Salient data (data considered by the authors as appropriate to assess for association with LUTS) relating to variables were extracted from each questionnaire (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables assessed as potential risk factors for owner-reported lower urinary tract signs in cats aged 18 months enrolled in the Bristol Cats Study

| Variable | Description | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Sex of cat reported by owner | Male Female |

| Breed | Breed | DSH/DLH Pedigree |

| Diet (at 12 months and 18 months) | Owners asked to state which food type(s) they fed their cat and in what proportions | 100% wet Mostly wet 100% dry Mostly dry 50:50 Mix (wet, dry, fresh) Fresh (100% and ‘mostly’) |

| Change in diet between 12 months and 18 months of age | Did the diet category change between 12 months and 18 months of age? | No Yes |

| Multi- or single-cat household (12 months and 18 months) |

This variable was derived from questions the owner was asked about how many cats had joined or left the household | Multi-cat Single cat |

| Change in multi-/single- cat household status between 12 months and 18 months of age | Did the household change from single- to multi-cat or multi- to single-cat between 12 months and 18 months of age? | Yes No |

| Age of neutering | Age at neutering, as stated by owner | ⩽4 months 5–6 months ⩾7 months Entire at 18 months |

| Number of cats in neighbourhood at 12 months and 18 months of age | Number of cats reported by the owner to be in the neighbourhood at 12 months and 18 months of age | None 1–5 6–10 ⩾11 |

| Visiting cats (12 months and 18 months) |

This variable was derived from three separate questions. The owner was asked if any of the cats in the neighbourhood: (1) come into their house; (2) come into their garden; or (3) stare through cat flaps, doors or windows | Yes No Don’t know |

| Reaction to the ‘visiting’ cats (12 months and 18 months)* |

Owners were asked how their cat reacted if the cat saw any of the visiting cats in their house or garden | Positive Negative No reaction Mixed reaction |

| Indoor and outdoor lifestyle (12 months and 18 months) |

Owners were asked what the outdoor access of their cat was | Indoor only Indoors but outside on a lead or in a run Outdoors and indoors Outdoors only |

| Change in indoor and outdoor lifestyle between 12 months and 18 months of age | Did the indoor and outdoor lifestyle category change between 12 months and 18 months of age? | Yes No |

| Moved house (18 months) |

Had the owner moved house in the past year? | Yes No |

| BCS (18 months) |

Owner-reported body condition score | 1 (very thin) 2 (thin) 3 (ideal) 4 (overweight) 5 (obese) |

| Interaction with other cats in household (18 months) † | If the household was a multi-cat household, owners were asked to report how their cat interacted with other cats in the household | Positive reaction Negative reaction Indifferent/no reaction Mixed reaction |

| Been in fight in past 6 months (18 months) |

Owners were asked to report if their cat had been in a fight with another cat in the past 6 months | Yes No |

| Age of questionnaire completion (18–48 months) |

The age of the cat as reported by the owner at the completion of Q4 (18 m), Q5 (30 m) and Q6 (48 m) | Age in months |

The categories in this variable were derived from the answers provided by the owner; a positive response was defined if the cat only reacted in a positive way (‘rubs against them’, ‘licks or grooms them’, ‘plays with them’, ‘skirts around them’), a negative response if the cat reacted only in a negative way (‘hisses or spits’, ‘chases them’, ‘swipes his/her paw’, ‘runs away’), no reaction if the cat only reacted in an indifferent way (‘ignores them’, ‘stays still’), and a mixed response if they had a positive and/or negative and/or no reaction

The categories in this variable were derived from the answers provided by the owner; a positive response was defined if the cat only reacted in a positive way (‘shares a sleeping place with another cat’, ‘grooms another cat’, ‘is groomed by another cat’, ‘rubs on another cat’, ‘is rubbed on by another cat’, ‘plays with another cat’), a negative response if the cat reacted only in a negative way (‘chases another cat’, ‘is chased by another cat’, ‘hisses or spits at another cat’, ‘is hissed or spat at by another cat’, ‘is reluctant to pass another cat in a narrow space; eg, doorway’, ‘blocks or inhibits the movement of another cat’), an indifferent/no reaction if the cat only reacted in an indifferent way (‘sleeps in the same room as another cat, but not close together’), and a mixed response if they had a positive and/or negative and/or indifferent/no reaction.

DSH = domestic shorthair; DLH = domestic longhair; BCS = body condition score; Q4 = questionnaire 4; Q5 = questionnaire 5; Q6 = questionnaire 6

All cats in the cohort were at least 18 months old at the time of analysis. The cut-off date for inclusion of cats into the 30 month and 48 month analysis was 1 June 2015; data from questionnaires received after this date were not included.

Descriptive statistics

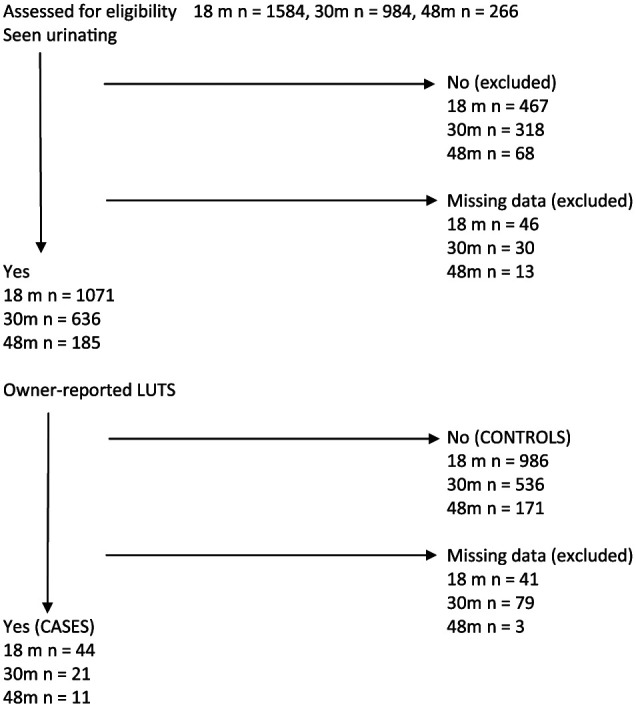

The prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of owner-reported LUTS at 18, 30 and 48 months of age were calculated based on the data summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing how the final numbers of cases and controls for the descriptive statistics of owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) among cats enrolled on the ‘Bristol Cats Study’ at 18, 30 and 48 months were determined

Case (LUTS) and control (no LUTS) definitions

Cases were defined as those cats whose owners had answered ‘yes’ to seeing the cat urinating and also answered ‘yes’ to at least one of the following ‘LUTS questions’: ‘Which, if any, of the following have you been aware of whilst watching your cat urinating?’; ‘He/she strains or appears to have difficulty urinating’; ‘He/she has passed blood when urinating’; ‘He/she vocalises (eg, meows) before or during urination’.

Control cats were defined as those cats whose owners had answered ‘yes’ to seeing the cat urinating and had answered ‘no’ to all of the LUTS questions outlined above.

We chose to include only those cats whose owners had seen them urinating for case and control selection, to reduce misclassification. For example, blood could be observed in the litter tray, but unless the owner had seen the cat passing urine to know that it had come from haematuria, one could not exclude that the blood had come from another source such as a wound or haematochezia (although this is rare). Owners are more likely to notice cases rather than controls. For example, if the cat vocalises during urination, the owner is more likely to notice the problem. This may overestimate the prevalence, as cats not seen urinating were excluded. It is likely those cats not seen were less likely to have LUTS in the first place. To take this into account, the prevalence (and 95% CIs) were calculated using data that included those cats that the owner had not seen urinating to provide the lowest prevalence estimate for owner-reported LUTS with the assumption that all cats not seen urinating did not have LUTS.

Risk factor analysis of variables associated with LUTS at 18 months

A case-control study to investigate risk factors for owner-reported LUTS in study cats at the age of 18 months was conducted. Cats with LUTS and cats without LUTS were identified from the dataset, using the criteria outlined above. Cats were excluded from the risk factor analysis if the owner had not seen the cat urinating, if they answered ‘don’t know’ for all three owner-reported signs, or a mixture of ‘no’ and ‘don’t know’ for the three owner-reported signs (on the basis that a ‘don’t know’ answer could not be defined as ‘no’ or ‘yes’).

Potential risk factors (summarised in Table 1) were tested, using univariable logistic regression models, for their association with LUTS at 18 months of age. Where appropriate, the number of categories of each variable was reduced by combining categories. BCS was dichotomised into 1–3 and 4–5, as the area of interest was a high BCS. Similarly with diet, 100% dry, mostly dry, 50:50, true mix and fresh food were grouped together, as the univariable analysis did not suggest a link between dry diet (100% dry or mostly dry) and risk of LUTS.

For the variables of interaction with other cats in the household at 18 months and change in household type (single/multi-cat household between 12 months and 18 months) there were no cases in one of the categories. To enable the univariable models to run, a control cat was selected at random for each model and altered to become a case and the model was run. The data were analysed in their original format for all other univariable analyses.

Variables with a P value <0.2 were considered for inclusion in a multivariable logistic regression model. The multivariable model was built using backward elimination; variables with P values <0.05 were retained in the model, and the change in deviance was assessed to determine the best model fit. Owing to missing data for some variables, the final multivariable model was based on data for 33 cases and 796 controls. Clustering within the dataset arising from some households owning more than one study cat was considered to be minimal, so was not accounted for owing to very small group sizes and unbalanced data. 19 Out of the cases and controls (33 cats and 796 cats, respectively) there were 144 single cat households and 650 multi-cat households (35 cats had missing data for the household type).

The sample size was determined by the number of questionnaires completed by 1 June 2015 and was estimated to have 80% power to detect odds ratios of 3.0 or more, based on a 95% level of confidence and assuming that 25% of controls were exposed to risk factors (Epi Info 2000 Online, available from http://epitools.ausvet.com.au/content.php?page=CIProportion).

IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 was used for data analysis.

The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Bristol’s ethics committee (reference UIN/13/026). Owners gave fully informed consent for the use of their data, and their data were used in accordance with the Data Protection Act.

Results

The numbers of completed questionnaires available for analysis at the time of the study were as follows: 3 months, n = 2172; 7 months, n = 1900; 12 months, n = 1716; 18 months, n = 1586; 30 months, n = 1159; 48 months, n = 248. Not all respondents completed all questions, resulting in additional missing data in each questionnaire. Figure 1 details how the numbers of cases and controls were determined.

Descriptive statistics

Of those cats seen urinating, a combination of owner-reported LUTS was observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of cats (seen urinating by their owners) with the signs used to define the outcome of owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) in cats enrolled in the Bristol Cats Study at 18 months, 30 months and 48 months

| Owner-reported LUTS | 18 months | 30 months | 48 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straining only | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) |

| Blood only | 7 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Vocalising only | 27 (2.6) | 15 (2.7) | 7 (3.8) |

| Vocalising and straining | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Vocalising and blood | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Straining and blood | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Vocalising, straining and blood | 7 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.1) |

| No LUTS | 986 (95.7) | 536 (96.2) | 171 (94.0) |

| Total number of cats seen urinating | 1030 | 557 | 182 |

Data are n (%)

The prevalence estimates and 95% CIs of owner-reported LUTS at 18 months, 30 months and 48 months are summarised in Table 3, based on cats that were observed urinating by their owners and for all cats (including those whose owners had not seen them urinating).

Table 3.

Prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) at 18 months, 30 months and 48 months for cats enrolled in the Bristol Cats Study

| Age (months) | Number of cats with owner-reported LUTS | Number of cats observed urinating | Prevalence (%) of LUTS for cats observed urinating (95% CI) | Number of cats (including those not seen urinating) | Prevalence of LUTS for all cats (including those not observed urinating) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 44 | 1030 | 4.3 (3.2–5.7) | 1497 | 2.9 (2.2–3.9) |

| 30 | 21 | 557 | 3.8 (2.5–5.7) | 875 | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) |

| 48 | 11 | 182 | 6.0 (3.4–10.5) | 250 | 4.4 (2.5–7.7) |

Completion of all three questionnaires (questionnaires at 18 months, 30 months and 48 months) were completed by the owners of 98 cats. Table 4 summarises owner-reported LUTS at the three time points for these 98 cats.

Table 4.

Number (%) of cats that had one or more owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) at 18, 30 and/or 48 months for the subsample of cats with owners who had completed questionnaires at 18 months, 30 months and 48 months for the Bristol Cats Study

| Time point/age of cat | Number (%) of cats with owner-reported LUTS |

|---|---|

| 18 months only | 4 (4.1) |

| 30 months only | 0 (0) |

| 48 months only | 6 (6.1) |

| 18 months and 30 months only | 0 (0) |

| 30 months and 48 months only | 0 (0) |

| 18 months, 30 months and 48 months | 2 (2.0) |

| 18 months and 48 months | 0 (0) |

| No time points | 86 (87.8) |

| Number of cats whose owners completed all three questionnaires (18 months, 30 months and 48 months) | 98 |

The results of the univariable logistic regression analyses are summarised in Table 5. Six variables had P values <0.2 and were thus carried forward to the multivariable model building process (these are highlighted in bold in Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariable logistic regression analysis of potential variables for owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) at 18 months in a UK cat cohort

| Variable | Number of cases (cats with owner-reported LUTS) (%) | Number of controls (cats without owner-reported LUTS) (%) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 25 (4.7) | 503 (95.3) | 1.0 | |

| Female | 18 (3.6) | 476 (96.4) | 0.39 | 0.76 (0.41–1.41) |

| Breed | ||||

| DSH/DLH | 27 (3.7) | 701 (96.3) | 1.0 | |

| Pedigree | 15 (5.5) | 256 (94.5) | 0.20 | 1.52 (0.80–2.91) |

| Diet at 12 months of age | ||||

| 100% wet or mostly wet | 14 (6.0) | 221 (94.0) | 1.0 | |

| All other diets | 22 (3.2) | 674 (96.8) | 0.06 | 0.52 (0.26–1.02) |

| Diet at 18 months of age | ||||

| 100% wet or mostly wet | 19 (6.9) | 255 (93.1) | 1.0 | |

| All other diets | 24 (3.4) | 682 (96.6) | 0.02 | 0.47 (0.25–0.88) |

| Change in diet between 12 months and 18 months of age | ||||

| No | 18 (5.6) | 303 (94.4) | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 17 (3.0) | 556 (97.0) | 0.06 | 1.94 (0.99–3.83) |

| Multi- or single-cat household at 12 months | ||||

| Single cat | 7 (4.1) | 164 (95.9) | 1.0 | |

| Multi-cat | 26 (3.5) | 718 (96.5) | 0.71 | 0.85 (0.36–1.99) |

| Multi- or single-cat household at 18 months | ||||

| Single cat | 7 (4.4) | 153 (95.6) | 1.0 | |

| Multi-cat | 26 (3.4) | 728 (96.6) | 0.57 | 0.78 (0.33–1.83) |

| Change in household type multi-/single- cat household status between 12 months and 18 months of age | ||||

| No | 1 (4.5) | 21 (95.5) | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 33 (3.7) | 859 (96.3) | 0.84 | 1.24 (0.16–9.50) |

| Age of neutering Up to 6 months of age | 28 (3.6) | 758 (96.4) | 1.0 | |

| ⩾7 months | 12 (7.7) | 144 (92.3) | 2.26 (1.12–4.54) | |

| Entire at outcome | 4 (6.6) | 57 (93.4) | 0.06 | 1.90 (0.64–5.60) |

| Number of cats in neighbourhood at 12 months of age | ||||

| None | 2 (2.7) | 72 (97.3) | 1.0 | |

| 1–5 | 19 (3.2) | 584 (96.8) | 1.17 (0.27–5.13) | |

| 6–10 | 12 (5.1) | 224 (94.9) | 1.93 (0.42–8.82) | |

| ⩾11 | 3 (7.9) | 35 (92.1) | 0.31 | 3.09 (0.49–19.32) |

| Number of cats in neighbourhood at 18 months of age | ||||

| None | 2 (2.7) | 73 (97.3) | 1.0 | |

| 1–5 | 29 (4.5) | 615 (95.5) | 1.72 (0.40–7.36) | |

| 6–10 | 9 (3.6) | 239 (96.4) | 1.37 (0.29–6.51) | |

| ⩾11 | 4 (7.5) | 49 (92.5) | 0.55 | 2.98 (0.53–16.90) |

| Visiting cats at 12 months of age | ||||

| Yes | 25 (4.1) | 579 (95.9) | 1.0 | |

| No | 9 (3.8) | 230 (96.2) | 0.80 | 0.91 (0.42– 1.97) |

| Visiting cats at 18 months of age | ||||

| Yes | 25 (3.8) | 641 (96.2) | 1.0 | |

| No | 5 (5.7) | 83 (94.3) | 0.39 | 1.55 (0.58–4.14) |

| Reaction to ‘visiting’ cats at 12 months of age |

||||

| Positive | 9 (3.4) | 259 (96.6) | 1.0 | |

| Negative | 11 (4.8) | 218 (95.2) | 1.45 (0.59–3.57) | |

| No reaction | 4 (4.2) | 92 (95.8) | 1.25 (0.38–4.16) | |

| Mixed reaction | 6 (4.3) | 134 (95.7) | 0.88 | 1.29 (0.45–3.70) |

| Reaction to ‘visiting’ cats at 18 months of age |

||||

| Positive | 15 (5.4) | 262 (94.6) | 1.0 | |

| Negative | 11 (3.8) | 277 (96.2) | 0.69 (0.31–1.54) | |

| No reaction | 4 (4.5) | 85 (95.5) | 0.82 (0.27–2.54) | |

| Mixed reaction | 5 (2.8) | 171 (97.2) | 0.59 | 0.51 (0.18–1.43) |

|

Indoor and outdoor lifestyle

at 12 months of age |

||||

| 100% indoors | 15 (7.1) | 195 (92.9) | 1.0 | |

| Outdoor access | 21 (2.8) | 726 (97.2) | 0.005 | 0.38 (0.19–0.74) |

|

Indoor and outdoor lifestyle

at 18 months of age |

||||

| 100% indoors | 18 (7.9) | 211 (92.1) | 1.0 | |

| Outdoor access | 26 (3.3) | 773 (96.7) | 0.003 | 0.39 (0.21–0.73) |

| Change in indoor and outdoor lifestyle between 12 months and 18 months of age | ||||

| No | 3 (2.3) | 129 (97.7) | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 33 (4.0) | 790 (96.0) | 0.34 | 0.56 (0.17–1.84) |

| Moved house in past year at 18 months of age | ||||

| Yes | 6 (6.5) | 86 (93.5) | 1.0 | |

| No | 38 (4.1) | 891 (95.9) | 0.28 | 0.61 (0.25–1.49) |

| BCS at 18 months of age | ||||

| 1, 2 or 3 | 38 (4.4) | 830 (95.6) | 1.0 | |

| 4 or 5 | 5 (3.8) | 125 (96.2) | 0.78 | 0.87 (0.34–2.26) |

| Interaction with other cats in household at 18 months of age | ||||

| Positive reaction | 1 (1.4) | 70 (98.6) | 1.0 | |

| Negative reaction | 2 (6.7) | 28 (93.3) | 5.0 (0.44–57.37) | |

| No or mixed reaction | 29 (3.9) | 712 (96.1) | 0.43 | 2.85 (0.38–21.25) |

| Been in fight past 6 months at 18 months of age |

||||

| Yes | 4 (2.4) | 160 (97.6) | 1.0 | |

| No | 12 (3.2) | 362 (96.8) | 0.63 | 1.33 (0.42–4.17) |

Variables in bold indicate those with a P value <0.2, which were considered for inclusion in the final multivariable model

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DSH = domestic shorthair; DLH = domestic longhair

The final multivariable model, built using the six variables with a P value <0.2, is summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Final multivariable logistic regression model for variables associated with owner-reported lower urinary tract signs (LUTS) at 18 months of age in a UK cat cohort

| Variable | Number (%) of cases (cats with owner-reported LUTS) | Number (%) of controls (cats without owner-reported LUTS) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor and outdoor lifestyle at 18 months of age | ||||

| Outdoor access | 19 (2.9) | 644 (97.1) | 1.00 | |

| Indoor only | 14 (8.4) | 152 (91.6) | 0.003 | 3.01 (1.47–6.17) |

| Change in diet between 12 months and 18 months of age | ||||

| No | 15 (2.8) | 520 (97.2) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 18 (6.1) | 276 (93.9) | 0.032 | 2.17 (1.07–4.39) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

From the multivariable model, an indoor-only lifestyle and a change in diet between 12 months and 18 months of age were identified as risk factors for owner-reported LUTS at 18 months of age. No clear type of change in diet was identified in our sample of case cats (Table 7).

Table 7.

Change of diet category and the number of cats that had a diet change between 12 months and 18 months of age

| Diet category change | Number of cats that changed diet type |

|---|---|

| 50:50 to mostly wet | 5 |

| Mostly wet to 50:50 | 3 |

| Mostly dry to 100% dry | 2 |

| 100% dry to mostly dry | 2 |

| Mostly dry to 50:50 | 1 |

| Fresh to mostly dry | 1 |

| 50:50 to mostly dry | 1 |

| Fresh to 50:50 | 1 |

| Mostly dry to mostly wet | 1 |

| Mostly wet to mostly dry | 1 |

| Total number of cases that had a diet change between 12 months and 18 months of age | 18 |

Discussion

The most important findings of this study were that the prevalence of owner-reported LUTS was higher than that previously reported for cats presenting to veterinary hospitals for LUTS or other reasons, and that a change in diet between 12 and 18 months of age and an indoor-only lifestyle at 18 months of age are risk factors for LUTS.

LUTS represent a common clinical problem in cats. To date, the majority of published studies of FIC were based on data collected from cats that had visited a veterinary practice because of their LUTS. It is unlikely that all cats displaying LUTS recognised by their owner are presented to a vet on the first instance of these signs. It is possible that the signs become more severe, or unacceptable to the owner (such as periuria) before these cats are presented to a vet; hence, the true prevalence of LUTS might be higher than reported in the literature and may occur at a younger age. LUTS can be linked to disease and be observed in healthy cats, so without a complete diagnostic investigation we cannot say whether the cats that showed LUTS in our study had FIC, if the signs were due to another cause of if they occurred in a healthy cat exposed to unusually threatening conditions. 20

We found prevalences of owner-reported LUTS of 4.5% at 18 months, 3.9% at 30 months and 6.4% at 48 months, which are higher than veterinary-reported data.3,4 However, it must be noted that the veterinary-reported prevalence cannot be directly compared with the owner-reported prevalence, as the cases in the owner reported prevalence study have not had a confirmed diagnosis of lower urinary tract disease, like the veterinary reported prevalence data did. We propose two reasons why this might be the case. First, the data in this study were based on owner-reported LUTS, whereas previously published prevalence estimates were based on data obtained from cats that had been presented to a veterinarian for LUTS. Second, assessing the prevalence of LUTS when including all study cats (ie, those seen and not seen urinating) the prevalence was 2.9% at 18 months, 2.4% at 30 months and 4.4% at 48 months. These lower numbers may be more accurate because they were less susceptible to bias arising from only including those cats seen urinating, which may have falsely increased the prevalence of owner-reported LUTS if cats with LUTS were more likely to have been seen urinating than cats without LUTS. This is because of the nature of LUTS; cats that pass urine more frequently, vocalise when urinating and urinate in inappropriate places in the house are more noticeable to their owner.

There are limitations to this study to be taken into account when interpreting the prevalence of owner-reported LUTS in this cohort of cats. We may have found a higher prevalence for LUTS than is true of the general population of cats within the UK for a number of reasons. By the nature of a long-term longitudinal study, the cohort consists of cats owned by highly motivated owners, who might be more likely to notice (and thus report) LUTS compared with a randomly selected population of cat owners. However, it could also be argued that such owners might provide a more accurate report of disease than less motivated owners who might miss signs of disease. As the LUTS were owner-reported, we cannot confirm that these cats actually had lower urinary tract disease. Some clinical records for cats are potentially accessible, but this relies on the owner having taken the cat to a veterinarian because of the LUTS in the first instance, which we suspect is not always the case. It must be noted that the owner-reported LUTS ‘haematuria’ was not confirmed by urinalysis; therefore, haemoglobinuria or myoglobinuria cannot be excluded in these cases, which are not necessarily linked to FIC. Our case definition included cats that, for example, might have had just one episode of vocalising while urinating, which potentially led to some misclassification of controls as cases.

Vocalising when urinating was the single most commonly reported LUTS and represented 61–71% of all cats with owner-reported LUTS (see Table 2). However, it should be noted that the owner-reported sign of ‘vocalising before or during urination’ may not be a direct indicator of LUTS. If cats were vocalising for other reasons then our prevalence estimates will have been over-estimated; however, anecdotal reports and the personal experience of the authors suggests that vocalisation before/during urination is a commonly used owner-reported sign of LUTS used by veterinarians in practice. LUTS reported by owners at different times suggested that the signs were intermittent rather than persistent, and only two cats had LUTS at all three questionnaire times (see Table 4). It is likely that if LUTS are intermittent and mild, then cats may not be presented to a vet. Although we did not collect data on the severity of LUTS, it could be speculated that the prevalence of LUTS in the general cat population is higher than suggested by data collected from veterinary practices.

Risk factors for owner-reported LUTS at 18 months of age

Results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated that an indoor-only lifestyle and a change in diet between 12 and 18 months of age were both significantly associated with an increased risk of owner-reported LUTS at 18 months of age (see Table 6). The finding of a change in diet between 12 and 18 months of age being significantly associated with an increased risk of owner-reported LUTS is interesting. As indicated in Table 7, there was no apparent pattern to the type of change in diet that was associated with this increased risk. A change in diet could be a proxy for another event; for example, if another cat in the household was ill and the owner was advised to feed a different diet, then all cats in the house may have changed diets because of this. Another possibility is that the cat was showing LUTS and the owner changed the diet because of this, so the change in diet was a consequence of LUTS rather than a cause. It could be speculated that the change in diet itself may not have been the stressor, but an event such as a cat being unwell in the household could cause stress and hence LUTS. The type of diet was not retained in our multivariable model, yet a change in diet was, suggesting that it was the change in diet, rather than the diet itself that increased the risk for owner-reported LUTS. Only 18 cats had owner-reported LUTS and also had a change in diet, which represents a relatively small sample size. A larger sample size might provide more information on change in diet and how it affects owner-reported LUTS, and is an area where we recommend further research. A previous study reported that a diet high in dry food was associated with an increased risk of LUTS. 17 In this study, the categories of 100% dry, mostly dry, 50:50, true mix and fresh food were grouped together as the univariable stage of analysis did not identify a link between a dry diet (100% dry, or mostly dry combined) and owner-reported LUTS compared with any other category.

In contrast to previous research, where cats in multi-cat households, cats with conflict between cats living in the same household, cats with high BCS, male cats and pedigree cats were reported to be more likely to have FIC,1,17 we found no evidence of a significant association between these factors and owner-reported LUTS at 18 months of age (see Table 5). Reasons for this contrast in findings between our study and previously published studies could be because the LUTS used for our case and control definitions were owner-reported only, whereas the studies mentioned used cats previously diagnosed with LUTS or cats presented to veterinary practices because of their LUTS.1,17 The limited statistical power of our study may also account for the discrepancy between our results and published veterinary data. We did not find any significant evidence of association with neuter status between cases and controls, which is in agreement with other work. 21

Conclusions

The prevalence of owner-reported LUTS within this UK cat cohort was estimated to be at least 2.9% (95% CI 2.2–3.9%) at 18 months, 2.4% (95% CI 1.6–3.6%) at 30 months and 4.4% (95% CI 2.5–7.7%) at 48 months of age. We have also demonstrated evidence of an association between both a change in the diet between 12 and 18 months of age, and an indoor-only lifestyle, with owner-reported LUTS. We did not demonstrate a significant association between owner-reported LUTS and the more commonly reported risk factors of higher BCS, eating a dry diet, neuter status, breed or sex.

Acknowledgments

Emma Gale is thanked for providing administrative support for the Bristol Cats Study. Cheryl Gale, Freya Gruffydd-Jones, Sarah Hobbs, Jo Hockenhull, Megana Nedungadi, Elodie Tinland and Amber Whitmarsh are thanked for data entry of postal questionnaires.

Footnotes

Louise Longstaff’s post was funded by Zoetis.

Funding: Zoetis funded Louise Longstaff’s post while this study was conducted. Cats Protection funds Jane Murray’s post. WALTHAM funds Emma Gale’s post. The Langford Trust for Animal Health and Welfare funded this study. Additional funding was provided by the Indoor Cat Initiative of The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Accepted: 14 March 2016

References

- 1. Cameron ME, Casey RA, Bradshaw JWS, et al. A study of environmental and behavioural factors that may be associated with feline idiopathic cystitis. J Small Anim Pract 2004; 45: 144–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Westropp J, Buffington CAT. Lower urinary tract disorders in cats. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC. (eds). Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 7th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2010, pp 2069–2086. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaskell CJ. Feline urological syndrome (FUS) – theory and practice. J Small Anim Pract 1990; 31: 519–522. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lund EM, Armstrong PJ, Kirk CA, et al. Health status and population characteristics of dogs and cats examined at private veterinary practices in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 1336–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klausner J, Lund EM. State of pet health 2014. https://www.banfield.com/Banfield/media/PDF/Downloads/soph/Banfield-State-of-Pet-Health-Report_2014.pdf (2014, accessed March 7, 2016).

- 6. Kruger JM, Osborne CA, Goyal SM, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with lower urinary tract disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991; 199: 211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buffington CA, Chew DJ, Kendall MS, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with nonobstructive urinary tract diseases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997; 210: 46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lekcharoensuk C, Osborne CA, Lulich JP. Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract diseases in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001; 218: 1429–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraijer M, Fink-Gremmels J, Nickel RF. The short-term clinical efficacy of amitriptyline in the management of idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease: a controlled clinical study. J Feline Med Surg 2003; 5: 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gerber B, Boretti FS, Kley S, et al. Evaluation of clinical signs and causes of lower urinary tract disease in European cats. J Small Anim Pract 2005; 46: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eggertsdottir AV, Lund HS, Krontveit R, et al. Bacteriuria in cats with feline lower urinary tract disease: a clinical study of 134 cases in Norway. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Defauw PA, Van de Maele I, Duchateau L, et al. Risk factors and clinical presentation of cats with feline idiopathic cystitis. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 967–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saevik BK, Trangerud C, Ottesen N, et al. Causes of lower urinary tract disease in Norwegian cats. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dorsch R, Remer C, Sauter-Louis C, et al. Feline lower urinary tract disease in a German cat population. Tierärztliche Praxis Kleintiere 2014; 42: 231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gunn-Moore DA. Feline lower urinary tract disease. J Feline Med Surg 2003; 5: 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Defauw PAM, Van de Maele I, Duchateau L, et al. Risk factors and clinical presentation of cats with feline idiopathic cystitis. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 967–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones BR, Sanson RL, Morris RS. Elucidating the risk factors of feline lower urinary tract disease. N Z Vet J 1997; 45: 100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lekcharoensuk C, Osborne CA, Lulich JP. Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract diseases in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001; 218: 1429–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarke P. When can group level clustering be ignored? Multilevel models versus single-level models with sparse data. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CA. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buffington CAT, Westropp JL, Chew DJ, et al. Risk factors associated with clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease in indoor-housed cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006; 228: 722–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]