Abstract

Objectives

The objective was to assess the medium- and long-term outcomes (radiographic and owner questionnaire) of feline tibial diaphyseal fractures with orthogonal plate fixation via a minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) approach.

Methods

Medical records and radiographs of cats that had tibial diaphyseal fractures stabilised with orthogonal plates were obtained (2012–2016). Immediate postoperative radiographs were reviewed to assess the construct configuration and follow-up radiographs (where available) were used to assess bone healing and implant-related complications. An owner-completed questionnaire (feline musculoskeletal pain index [FMPI]) was used at a minimum of 6 months following surgery to assess the cats’ ability to perform normal activities.

Results

Eight feline tibial diaphyseal fractures met the inclusion criteria. One major complication was observed, most likely due to an operative technical error. There were no further complications following revision surgery. Six of the eight cases that had radiographic follow-up either had clinical bone union or showed evidence of bone healing. All cases were classified as successful according to FMPI.

Conclusions and relevance

Orthogonal plating of feline tibial diaphyseal fractures via an MIPO approach resulted in successful outcomes and a lower complication rate compared with previously reported techniques.

Introduction

Tibial fractures are common in cats,1–3 with a significant proportion of these fractures occurring in the mid- to distal-third of the diaphysis.1,4–7 Various methods have been described for fixation of tibial fractures, including the use of standard external skeletal fixators (ESFs), circular-linear hybrid ESFs and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with either a single plate or a plate in combination with an intramedullary device (‘plate-rod’).5–8

Tibial diaphyseal fractures were reported to account for 11/18 of feline non-union fractures. 2 Proposed causes of delayed/non-union in feline tibial diaphyseal fractures include biological compromise (inadequate blood supply from the limited extraosseous soft tissues and limited arborisation of the intramedullary circulation)9–11 and mechanical compromise (insufficiently stable fixation, excessive fracture gaps and interposition of soft tissue in the fracture gap).2,3,9 In two recent studies of feline tibial diaphyseal fracture repair the incidence of non-union was 22.8–37.5%,5,6 and fixation with ESFs significantly increased the rate of complications compared with ORIF. 6 However, the incidence of plate bending was 13% (8/60) in a study of feline tibial fractures managed with a medial plate or a medial plate-rod combination. 7 The authors of that study suggested that failure of plates by bending was indicative of acute overload (rather than cyclical failure), implying that plate strain was excessive. 7 It is widely accepted that distal tibial fractures in cats are biologically compromised, such that fixation of such fractures should be suitably robust to withstand acute and cyclical loading. Where flexible bridging osteosynthesis is utilised for fractures that are both non-reconstructable (ie, non-load-sharing) and biologically compromised, implant failure prior to bone healing is a predictable consequence.

Robust fixation may involve dual-plate fixation, which has been used in the human field for many years,12–14 often as an option for revision of non-union fractures.14,15 The success of a dual-plate construct has been ascribed to high axial and rotational stiffness, and therefore long-term stability, despite a high-strain environment.7,15–17 Dual-plate fixation for the initial repair and for the revision of failed plate osteosynthesis in feline diaphyseal tibial fractures has been documented.7,18

The importance of minimising iatrogenic biological compromise during fracture fixation is well recognised.19–22 Standard ORIF requires soft tissue dissection and periosteal elevation, resulting in compromise to the extraosseous blood supply on which early callus formation relies.1,2,23–25 Techniques such as ‘open-but-do-not-touch’ and minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) emphasise the importance of soft tissue preservation over anatomical reconstruction.19,21,26 Such techniques have been associated with shorter healing times and fewer complications in the human field,22,27–29 and in some small veterinary series.19,21

The purpose of this study was to report the medium- to long-term outcomes (radiographic and owner questionnaire) for orthogonal plate fixation of feline tibial diaphyseal fractures via a MIPO approach.

Materials and methods

Data

Case records of cats with tibial fractures treated at a single veterinary referral centre (Southern Counties Veterinary Specialists) between May 2012 and September 2016 were reviewed. Criteria for inclusion in this study were feline tibial diaphyseal fractures treated by fixation with orthogonal non-locking plates via a MIPO approach; complete medical records; and preoperative and immediate postoperative radiographs of the tibia. Information collected included signalment (breed, sex, age, weight), presence of comorbidities, time to surgery, the fracture type (open or closed), the size of the implants used and any postoperative complications. Open fractures were further classified into grades 1–3 on the basis of soft tissue disruption, as previously described. 30 Complications were defined as major (surgical intervention required) or minor (managed without surgical intervention).

Surgical technique

Cats were anaesthetised according to standard protocols used in our hospital. After routine preparation, the patient was positioned in dorsal recumbency to allow access to the medial and cranial aspects of the tibia. The proximal incision (approximately 2–3 cm) was made craniomedially on the skin overlying the proximal tibial diaphysis or metaphysis, depending on the length of the plate. Sharp dissection elevating the pes anserinus was performed to expose the proximal tibia. For cases that had a short cranial plate, the screws in the proximal fragment were placed through a separate, short (approximately 2 cm) cranial incision. The distal skin incision (approximately 3 cm) was centred over the distal tibial epiphysis craniomedially and dissection was performed through the soft tissues to expose the medial tibial malleolus. Epiperiosteal bone tunnels were created between the incisions to allow placement of two veterinary cuttable plates (VCPs).

No attempt was made to visualise the fracture and fluoroscopy was not utilised. Medial plates were applied first, ensuring appropriate alignment of the hock and stifle joints. If an oblique fracture was present then pointed reduction forceps (Veterinary Instrumentation) were placed transdermally, to aid in reduction and temporary stabilisation of the fracture prior to application of the medial plate. A cranial plate was then applied. Owing to the feline tibia being relatively straight, minimal or no contouring of the plates was performed prior to application. Following lavage, the soft tissues were closed in layers with intradermal monofilament absorbable sutures and the incisions coated with a Dermabond adhesive seal (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson Medical).

Radiographic assessment

Preoperative radiographs were assessed digitally (Osirix version 6 64-bit open-source DICOM viewer; http://www.osirix-viewer.com/OsiriX-64bit.htm) to record the following: fracture location on tibia, fracture orientation (transverse, short oblique, long oblique, spiral) and the degree of comminution (none, mild = <3 fragments, moderate = 4–5 fragments, severe = >5 fragments). 30

The following variables were obtained for both the medial and cranial plates from the postoperative orthogonal tibial radiographic views: plate-bridging ratio (PBR; ratio of the plate length to the bone length), working length (WL; expressed as the number of empty plate screw holes between the proximal and distal screws closest to the fracture, and as a percentage of the tibial length spanned by this section of plate), plate screw density (PSD; ratio of the number of screws inserted to the total number of screw holes in the plate), the distance from distal-most screw to the talocrural joint, screw to bone diameter ratio at the isthmus of the bone and the accuracy of fracture reduction (mediolateral and craniocaudal translation and maximum fracture gap, measured in millimetres). PBR, WL and PSD were calculated as previously reported.31,32 In the absence of contralateral tibial radiographs (for comparison) and specific reference values for joint orientation angles, objective assessment of tibial alignment following fracture repair was not possible; therefore, subjective assessment was performed.5,33–35 Mediolateral translation was defined as the ratio between maximum displacement in the caudocranial radiographic view and the mediolateral diameter of the diaphysis at that level. 36 Fracture gap was recorded as the maximum absolute gap in either radiographic view, measured in millimetres. 36

Follow-up radiographs, when available, were assessed for radiographic signs of clinical union (defined as presence of a bridging callus or a callus >50% of the tibial diameter at the level of the fracture site on 3/4 cortices on two orthogonal views)5,21 and evidence of any implant-related complications.

Owner questionnaire

All clients were contacted and asked to complete version 9 of the ‘feline musculoskeletal pain index’ (FMPI) questionnaire obtained from North Carolina State University. This owner-completed questionnaire examines the ability of cats to perform normal feline activities at the time of contact. The use of the FMPI for assessment of clinical function in cats with naturally occurring osteoarthritis (and their response to medical management) has been described and validated.37–39 The questionnaire includes 17 numerically weighted questions regarding the cat’s ability to perform different activities, and two visual analogue scale (VAS) questions related to pain intensity (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary material). Scores from 0 to 4 are assigned from the owners’ response to each of the 17 questions (0 = unable to perform activity, 4 = normal). The pain-intensity questions required owners to rate their cat’s level of pain on a standardised 100 mm VAS. Scores on the VAS were calculated by measuring, in mm, from the start (zero point) to the owner’s mark, with 100 indicating ‘no pain’, and then dividing by 25 to provide these questions with a numerical value between 0 to 4. 39 The total score for the 19 items could, theoretically, range from 0 (cats unable to perform any activity) to 76 (cats normal for every activity), and the scores were converted to a percentage. A FMPI score of 90–100% was considered a success, 39 that is, the cat returned to pre-injury levels of activity. Any score <90% was considered a failure. Questionnaires were performed a minimum of 6 months following surgery, providing medium- to long-term evaluation of function.

Results

Between May 2012 and September 2016, 18 cats were presented with tibial fractures. Of these, 10 were treated with orthogonal plates, two of which were excluded owing to lack of follow-up. All data from the study have been included in Appendix 2 in the supplementary material.

Breeds included six domestic shorthairs, one Siamese and one Bengal cross-breed. There were four males and four females. Mean age was 2.95 years (range 7 months to 6 years). Mean body weight was 4.0 kg (range 3.1–5.3 kg).

Tibial fractures were located in the distal third of the diaphysis in six cases and the central third of the diaphysis in two cases. Fracture orientations were spiral (n = 4), oblique (n = 2) and segmented (n = 2) and comminution ranged from absent to moderate. Of the eight fractures, one was open type 1, and the remaining seven were closed. Six of the eight tibial diaphyseal fractures were accompanied by fibular fractures, which occurred at the same proximodistal level as the tibial fracture in all cases. The mean time between injury and surgery was 2.6 days (range 1–4 days).

All fractures were fixed with two orthogonal VCPs (Veterinary Instrumentation, Sheffield) performed via a MIPO technique. Two cases had a reconstruction VCP placed cranially rather than a standard plate. The plate sizes used were either a 1.5 or 2.0 mm cranially, and a 2.0 or 2.4 mm medially with varying combinations in the number of screws per plate per fragment (ranging from 1–4) and screw sizes (1.5, 2.0 or 2.4 mm) (Table 1). Plate and screw size selection, in relation to body size and anatomical region, fell within the recommended guidelines outlined in the AO Foundation small animal manual. 40

Table 1.

Details of the medial and cranial plate and screw combinations used in all cases

| Case number | Medial plate and screw combination | Cranial plate and screw combination | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate used | Working length (screw holes/% of tibial length) | Screws in proximal fragment | Screws in distal fragment | Plate used | Working length (screw holes/% of tibial length) | Screws in proximal fragment | Screws in distal fragment | |

| 1 | 2.0 mm 16-hole VCP | 11/49% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 12-hole reconstruction VCP | 8/40% | Two 1.5 mm | Two 1.5 mm |

| 2 | 2.4 mm 18-hole VCP | 13/63% | Two 2.4 mm | Two 2.4 mm | 2.0 mm 18-hole VCP | 14/52% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

| 3 | 2.0 mm 19-hole VCP | 10/59% | Four 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 17-hole VCP | 11/56% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

| 4 | 2.0 mm 15-hole VCP | 8/42% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 12-hole VCP | 8/43% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

| 5 | 2.0 mm 18-hole VCP | 11/31% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 16-hole VCP | 10/26% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

| 6 | 2.0 mm 23-hole VCP | 12/76% | Three 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 17-hole reconstruction VCP | 11/42% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

| 7 | 2.0 mm 26-hole VCP | 22/75% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm | 2.0 mm 20-hole VCP | 7/26% | Two 2.0 mm | One 1.5 mm and one 2.0 mm |

| 8 – initial surgery | 2.4 mm 15-hole VCP | 11/53% | Two 2.4 mm | Two 2.4 mm | 2.4 mm 13-hole VCP | 7/38% | Two 2.4 mm | Two 2.4 mm |

| 8 – revision surgery | 2.4 mm 20-hole VCP | 8/51% | Four 2.0 mm | Three 2.0 mm | 2.4 mm 15-hole VCP | 10/51% | Two 2.0 mm | Two 2.0 mm |

VCP = veterinary cuttable plate

The successful fracture repairs (an example of one case is shown in Figure 1) had plate length and screw configurations as follows: mean PBRs of 0.85 (medial) and 0.64 (cranial); mean PSDs of 0.23 (medial) and 0.26 (cranial); mean plate WLs were 11.4 (medial) and 9.6 (cranial) screw holes; and 53.2% (medial) and 40.2% (cranial) when expressed as a percentage of the tibial length; screw to bone diameter ratio had mean values of 0.25 (range 0.23–0.29) for the medial plate and 0.25 (range 0.21–0.29) for the cranial plate. The screw configurations for the initial repair and the revision surgery of case 8 are highlighted in Table 2, to allow comparison of the mean values for all successful repairs.

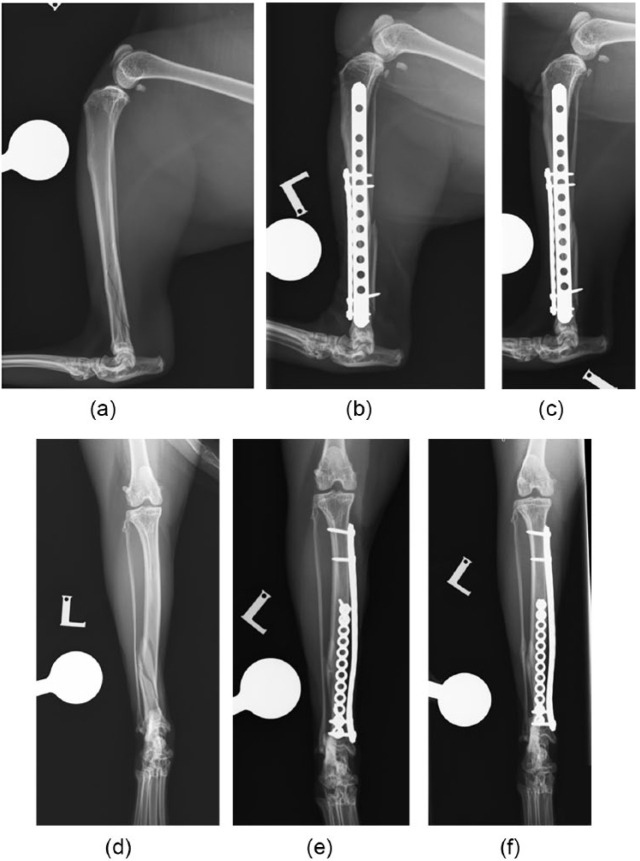

Figure 1.

(a–c) Mediolateral and (d–f) caudocranial radiographs were taken (a,d) preoperatively, revealing a spiral, segmental fracture of the distal one-third diaphysis of the tibia; (b,e) immediately postoperatively, revealing satisfactory implant positioning and alignment, and mild caudal displacement of the segmental fragment (a 16-hole 2.7 mm veterinary cuttable plate [VCP] was placed medially with two 2.4 mm screws proximally and distally, and a 12-hole 2.0 mm reconstruction VCP with two 2.0 mm screws proximally and distally); and (c,f) 29 days following surgery, revealing no implant-related complications and new bone formation at the fracture site consistent with mineralised callus formation

Table 2.

Details of plate length and screw configurations for all successful repairs (expressed as a mean value) and for the initial and revision surgery of case 8

| Mean values for all successful repairs (± SD) |

Case 8 initial repair |

Case 8 revision surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | Cranial | Medial | Cranial | Medial | Cranial | |

| Screw to bone diameter ratio | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Plate screw density | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.2 | 0.27 |

| Plate-bridging ratio | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.64 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.54 | 0.85 | 0.67 |

| Plate working length (% of tibial length) | 53.2 ± 17.6 | 40.2 ± 11.3 | 53 | 38 | 33 | 51 |

| Distance from distal most screw to talocrural joint (mm) | 2.95 ± 0.89 | 11.1 | 1.93 | |||

Postoperative radiographs revealed satisfactory fracture reduction with mean translation at the fracture of 7.6% of the tibial diaphyseal width (range 0–37%) and mean maximum fracture gap of 2.4 mm (range 0–6.6 mm).

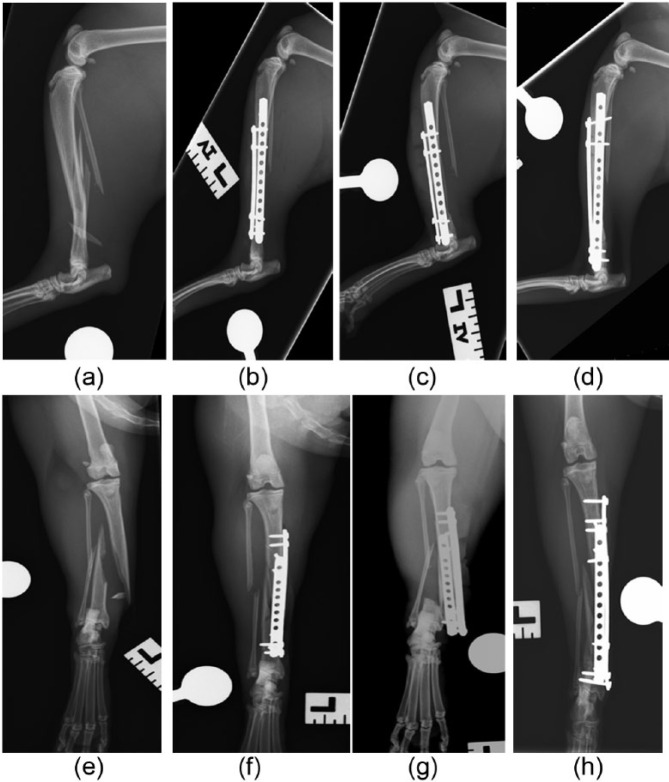

A major complication occurred in case 8; the remaining cases had no minor or major complications. In case 8, the tibia fractured through the distal most screws of the medial and cranial plates, approximately 48 h after the initial surgery. Surgery was revised, placing longer plates, which increased the PBR from 0.7 to 0.85 and 0.54 to 0.67 in the medial and cranial plates, respectively (Figure 2). The distance from distal-most screw to the talocrural joint was also reduced from 11.1 mm to 1.93 mm. The screw sizes were changed from 2.4 mm to 2.0 mm. No further complications were observed following the revision surgery and healing was unremarkable.

Figure 2.

(a–d) Mediolateral and (e–h) caudocranial radiographs were taken (a,e) preoperatively, revealing a spiral fracture of the mid-third diaphsysis of the tibia and a fibular fracture at the same level; (b,f) immediately postoperatively, revealing satisfactory implant positioning and alignment (a 15-hole 2.4 mm veterinary cuttable plate [VCP] was placed medially with two 2.4 mm screws proximally and distally, and a 13-hole 2.4 mm VCP with two 2.4 mm screws proximally and distally); (c,g) 48 h following surgery, revealing fracture of the tibia through the distal screws of the medial and cranial plates; (d,h) and after postoperative revision surgery, revealing satisfactory implant positioning and alignment (a 20-hole 2.4 mm VCP was placed medially with four 2.0 mm screws proximally and three 2.0 mm distally, and a 15-hole 2.0 mm VCP with two 2.0 mm screws proximally and distally)

Radiographic follow-up was available for six of the cases, with a mean time from surgery of 47 days (range 24–95 days). Clinical union was evident in three cases, with the remaining three cases showing subjective evidence of bone healing and callus formation. The mean time for follow-up with the FMPI was 555 days (range 186–1610 days). The outcome was considered successful in all cases when assessed by the FMPI, with five cases achieving a score of 100% and three scoring 98.6%.

Discussion

The high complication rate when repairing feline diaphyseal tibial fractures implies that previously reported fixation methods are not appropriate for all cases.2,5–7 Previously reported complications may be attributed to both inadequate construct selection and disturbance of the fracture site biology.5–7 This study reports the outcomes of eight cats with tibial diaphyseal fractures undergoing fixation with orthogonal VCPs and conventional screws (1.5/2.0/2.4 mm) performed via an MIPO technique. Outcome measures were short-term radiographic assessment (six cases) and medium- to long-term follow-up was by client questionnaire. One major complication was experienced, involving failure of the tibia through the distal-most 2.4 mm tibial screw.

MIPO has been described for tibial fracture management in dogs and cats.21,22 It has been shown that the distal tibia has a poorer extraosseous blood supply when compared with the proximal tibia in humans. 41 A similarly limited extraosseous blood supply to the feline distal tibia may be hypothesised to contribute to the high incidence of fracture non-union in previous studies.2,5,6 With this in mind, biological osteosynthesis emphasises preservation of the soft tissues surrounding the fracture site and may therefore be appropriate in tibial diaphyseal fracture management.19,21,23,26,35 One disadvantage of conventional (ie, non-locking) plate application is iatrogenic disruption of the extraosseous blood supply. 41 This could be theoretically worsened by orthogonal plating, in which compression of the periosteum is applied from both the cranial and medial aspects of the bone.

The low mean PSD (0.21 and 0.25 for medial and lateral plates, respectively) and high mean PBR (0.85, when considering the medial plate, which was always longer) in our study are consistent with a biological approach.19,21,26,42 The PSDs for both the medial and cranial were lower than what has been previously reported (0.34–0.72).7,21,23,32 However, the screw holes in VCPs are close together, 21 potentially resulting in a relative increase in the number of empty holes compared with some other plating systems. The PBR for both the medial and lateral plates was comparable with previously reported values.7,21,32

WLs in our study had means of 56.1% and 40.3% of the tibial length, and 11.9 and 9.9 empty screw holes for the medial and cranial plates, respectively, which was higher than previous studies (23.8% and 3–6 screw holes).7,32 While the WL measured by screw holes will be increased by the high hole density in VCPs, the plate type has no influence on the WL measured by tibial length spanned. Increasing WL has been described to result in greater elasticity, which allows micro-motion at the fracture, potentially encouraging rapid formation of periosteal callus.24,43–45 A higher WL also lowers the pull-out forces exerted on the screws.24,44,45 The benefits of increasing WL have been disputed in a biomechanical study, which stated that WL had no influence on gap strain. 46 Other studies have also stated that when non-locking plates are used and the plates were contoured accurately to the bone, the WL was the length of the fracture itself.47,48

When plates are placed orthogonally, each plate will be effectively edge-loaded, increasing the implant’s area moment of inertia, which increases the resistance to bending.9,25,49 Therefore, the use of orthogonal plates in our study was likely to have eliminated any theoretical benefit of elasticity or dissipation of strain, which may have been obtained with a high WL. However, it remains theoretically possible that the benefit of lowered screw pull-out force, when WL is increased, was maintained. The authors would argue that maximising PBR is appropriate to prevent the stress riser effect of a plate ending in the diaphysis (particularly where this involves the isthmus of the bone, as in case 8, where fracture of the tibia was observed through the distal screw hole). High WL has several further advantages: avoidance of disruption of the fracture hematoma; minimisation of plate compression on the periosteal blood vessels close to the fracture site; and placement of screws for both plates through minimal (ie, short) approaches.19,21,24,26,42 To our knowledge there are no publications determining how PSD, PBR and WL influence the biomechanics of a construct when plates are placed orthogonally. Further clinical and biomechanical studies are required before definitive recommendations can be made.

Dual-plate fixation for treatment of fractures has been described both biomechanically and clinically in the veterinary and human literature.7,12–14,17,16,50,51 Orthogonal plating of the tibia provides greater construct stiffness during mediolateral bending and a higher failure load in axial compression when compared with single plating and plate-rod constructs. 16 This may account for the absence in the current study of the complication of plate bending, as reported in a recent study of similar fractures. 7 The use of orthogonal plates also allows increased screw purchase within small bone fragments. Achieving purchase of six cortices (ie, three bicortical screws, the current AO recommendations for non-locking plates) 40 in short bone fragments (eg, distal tibial fractures) with a single plate may be difficult or impossible. One solution to maximise fixation in short juxta-articular fracture fragments is the use of hybrid linear–circular ESFs. 52 However, in a case series of eight distal tibial fractures in cats a non-union rate of 37.5% (n = 3/8) was recorded, and the authors surmised that the mechanical environment was insufficiently rigid resulting in failure of callus mineralisation. 5 The high hole density of VCPs aids placement of several screws over a short distance. 21 However, the VCP is regarded as having relatively low stiffness, 53 therefore necessitating additional fixation (intramedullary device or orthogonal plating) in situations of high strain. Placement of orthogonal plates also allows the surgeon to maximise cortices purchased in a small distal fragment of bone since screws may be placed at almost the same level in two different planes. The disadvantage of having a large number of screws in a small segment is the potential for iatrogenic fracture secondary to stress riser creation, as observed in a single case in this study. We attributed this complication to a technical error, which may have occurred for a number of reasons: the screw diameter for the distal screws for both the medial and cranial plates were at the upper range of the current AO recommendations, 40 and were very close together; the most distal screw was 11.1 mm from the distal tibial joint surface, which was higher when compared with the other seven cases, which had an average distance of 1.72 mm (the increased distance from the joint surface will have increased the moment at the distal screw hole, increasing bone stress at that level). We would therefore recommend that at least one plate should span the full length of the tibia where possible (in our opinion, it is easier to achieve this with the medial plate), and that the distal-most screw should be as close to the joint as possible; finally, if the screw diameter becomes close to the upper end of the current AO recommendations, consider selecting a smaller-diameter screw.

When placing orthogonal plates to repair a fracture, there is a concern that the construct may be too stiff, resulting in ‘stress protection’ of the fracture site,17,54 that is, insufficient strain to stimulate osteoblast activity, persistence of non-mineralised callus and fracture non-union.25,54,55 However, this has been disputed by a human biomechanical study which showed that orthogonal plating of a 1 cm fracture gap did not necessarily exceed the stiffness of the intact model. 5 Furthermore, non-unions were not observed in our study, as all cases that had radiographic follow-up had either clinical union, or evidence of mineralised callus formation within the expected time frame. One limitation of the study was that radiographic follow-up was not available for 2/8 cases.

FMPI was used to assess the medium- to long-term functional outcome. The questionnaire is validated for assessment of behaviour in naturally occurring feline osteoarthritis.38,39 There is currently no validated questionnaire for assessing the outcomes of fracture repair in cats. However, the FMPI assesses a cat’s ability to perform normal activities, which was considered a reasonable assessment of outcome. Five cases had a score of 100% and three of 98.6%. Of the cases that achieved 98.6%, two cats dropped one point on their ‘jumping ability’ question (the cats in question were still happy to jump; however, the clients felt that the jumping was ‘not quite normal’ when compared with jumping before surgery) and the third cat dropped one point on its ‘grooming’ ability question (owing to occasional licking at the skin overlying the plate; despite this, no skin lesions from over-grooming requiring treatment had been observed in the 550 days prior to the FMPI questionnaire). Based on the FMPI results, all cats returned to pre-injury levels of activity.

In addition to the lack of complete radiographic follow-up for all cases, the retrospective nature and small sample size were limitations of our study. Furthermore, decisions on WL, PSD and PBR were not standardised or compared with a control group; therefore, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding these factors. Further studies with a larger sample size, better radiographic follow-up and comparison between a biological approach and ORIF using orthogonal plate fixation for tibial diaphyseal fractures are necessary for recommendations to be made.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that orthogonal plates may be employed in feline tibial diaphyseal fracture management, perhaps with fewer complications than previously reported for other fixation methods.5–7 We would advise that the medial plate has a high PBR, and that the distal screw is placed as close to the talocrural joint as possible, in order to mitigate the risk of iatrogenic fracture of the tibia.

Supplemental Material

Feline musculoskeletal pain index questionnaire

Raw data

Footnotes

Accepted: 9 January 2017

Supplementary material: The following files are available: Appendix 1: Feline musculoskeletal pain index questionnaire. Appendix 2: Raw data.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Boone EG, Johnson A L, Montavon P, et al. Fractures of the tibial diaphysis in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986; 188: 41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nolte DM, Fusco JV, Peterson ME. Incidence of and predisposing factors for non-union of fractures involving the appendicular skeleton in cats: 18 cases (1998–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 226: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harari J. Treatments for feline long bone fractures. Vet Clin Small Anim Pract 2002; 32: 927–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brunnberg L. Tibial and fibular fractures in the cat. Kleintierpraxis 2003; 48: 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Witte PG, Bush MA, Scott HW. Management of feline distal tibial fractures using a hybrid external skeletal fixator. J Small Anim Pract 2014; 55: 571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perry KL, Bruce M. Impact of fixation method on postoperative complication rates following surgical stabilization of diaphyseal tibial fractures in cats. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2015; 28: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morris AP, Anderson AA, Barnes DM, et al. Plate failure by bending following tibial fracture stabilisation in 10 cats. J Small Anim Pract 2016; 57: 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gemmill TJ, Cave TA, Clements DN, et al. Treatment of canine and feline diaphyseal radial and tibial fractures with low-stiffness external skeletal fixation. J Small Anim Pract 2004; 45: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeAngelis MP. Causes of delayed and non-union of fractures. Vet Clin North Am 1975; 5: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu C, Miclau T, Hu D, et al. Ischaemia leads to delayed union during fracture healing: a mouse model. J Orthop Res 2007; 25: 51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dugat D, Rochat M, Ritchey J, et al. Quantitative analysis of the intramedullary arterial supply of the feline tibia. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2011; 24: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korner J, Lill H, Müller LP, et al. The LCP-concept in the operative treatment of distal humerus fractures – biological, biomechanical and surgical aspects. Injury 2003; 34: SB20–SB30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Self J, Viegas SF, Buford WL, Jr, et al. A comparison of double-plate fixation methods for complex distal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El Haj M, Khoury A, Mosheiff R, et al. Orthogonal double plate fixation for long bone fracture nonunion. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2013; 80: 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kosmopoulos V, Nana AD. Dual plating of humeral shaft fractures: orthogonal plates biomechanically outperform side-by-side plates. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472: 1310–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glyde M, Day R, Deane B. Biomechanical comparison of plate, plate-rod and orthogonal locking plate constructs in an ex-vivo canine tibial fracture gap model [Abstract]. Proceedings of the ECVS 20th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2011; Ghent, Belgium. Zurich, Switzerland: ECVS, 2011, p 88. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Preston TJ, Glyde M, Hosgood G, et al. Dual bone fixation: a biomechanical comparison of 3 implant constructs in a mid-diaphyseal fracture model of the feline radius and ulna. Vet Surg 2016; 45: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fitzpatrick N. Challenging fracture fixation – what to do when it’s not in the book [abstract]. Proceedings of the BVOA Autumn Meeting; 2013; Manchester, UK. Gloucester, UK: BSAVA. 2013, pp 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson AL, Smith CW, Scheffer DJ. Fragment reconstruction and bone plate fixation versus bridging plate fixation for treating highly comminuted femoral fractures in dogs: 35 cases (1987–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dudley M, Johnson AL, Olmstead M, et al. Open reduction and bone plate stabilization, compared with closed reduction and external fixation, for treatment of comminuted tibial fractures: 47 cases (1980–1995) in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997; 211: 1008–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guiot LP, Déjardin LM. Prospective evaluation of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis in 36 non-articular tibial fractures in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2011; 40: 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerber C, Mast JW, Ganz R. Biological internal fixation of fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1990; 109: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reems MR, Beale BS, Hulse DA. Use of a plate-rod construct and principles of biological osteosynthesis for repair of diaphyseal fractures in dogs and cats: 47 cases (1994–2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 223: 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sarrau S, Meige F, Autefage A. Treatment of femoral and tibial fractures in puppies by elastic plate osteosynthesis. A review of 17 cases. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2007; 20: 51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perren S. Evolution of the internal fixation of long bone fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 2002; 84: 1093–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gautier E, Sommer C. Guidelines for the clinical application of the LCP. Injury 2003; 34: B63–B76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tong GO, Bavonratanavech S. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO). Davos: AO Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Collinge C, Sanders R, DiPasquale T. Treatment of complex tibial periarticular fractures using percutaneous techniques. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; 375: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Redfern DJ, Syed SU, Davies SJM. Fractures of the distal tibia: minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis. Injury 2004; 35: 615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DeChamp C, Johnston S, Dejardin L, et al. Fractures, classification, diagnosis and treatment. In: Brinker, Piermattei DL, Flo GL. (eds). Handbook of small animal orthopaedics and fracture repair. 5th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016, pp 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pozzi A, Hudson CC, Gauthier CM, et al. Retrospective comparison of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis and open reduction and internal fixation of radius-ulna fractures in dogs. Vet Surg 2012; 42; 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vallefuoco R, Le Pommellet H, Savin A, et al. Complications of appendicular fracture repair in cats and small dogs using locking compression plates. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2016; 29: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson AL. Current concepts in fracture reduction. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2003; 16: 59–55. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmoekel HG, Stein S, Radke H, et al. Treatment of tibial fractures with plates using minimally invasive percutaneous osteosynthesis in dogs and cats. J Small Anim Pract 2007; 48: 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hudson SS, Pozzi A, Lewis DD. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis: applications and techniques in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009; 22: 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piras L, Cappellari F, Peirone B, et al. Treatment of fractures of the distal radius and ulna in toy breed dogs with circular external skeletal fixation: a retrospective study. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2011; 24: 228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Benito J, Depuy V, Hardie E, et al. Reliability and discriminatory testing of a client-based metrology instrument, feline musculoskeletal pain index (FMPI) for the evaluation of degenerative joint disease-associated pain in cats. Vet J 2013; 196: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gruen ME, Griffith EH, Thomson AE, et al. A novel approach to the detection of clinically relevant pain relief in cats with degenerative joint disease associated pain. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 8: 346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gruen ME, Griffith EH, Thomson AE, et al. Criterion validation testing of clinical metrology instruments for measuring degenerative joint disease associated mobility impairment in cats. Plos One 2015; 10: e0131839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koch D. Implants: description and application. In: Johnson AL, Houlton JEF, Vannini R. (eds). AO principles of fracture management in the dog and cat. Clavadelerstrasse: AO Publishing, 2005, pp 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Borrelli J, Prickett W, Song E, et al. Extraosseous blood supply of the tibia and the effects of different plating techniques: a human cadaveric study. J Orthop Trauma 2002; 16: 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rozbruch SR, Muller U, Gautier E, et al. The evolution of femoral shaft plating technique. Clin Orthop 1998; 354: 195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McKibbin B. The biology of fracture healing in long bones. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1978; 60: 150–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grundnes O, Rekeras O. Effects of instability on bone healing. Femoral osteotomies studied in rats. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64: 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aro H, Chao E. Bone-healing patterns affected by loading, fracture fragment stability, fracture type, and fracture site compression. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993; 29: 8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maxwell M, Horstman CL, Crawford RL, et al. The effects of screw placement on plate strain in 3.5 mm dynamic compression plates and limited-contact dynamic compression plates. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009; 22: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pearson T, Glyde M, Hosgood G, et al. The effect of intramedullary pin size and monocortical screw configuration on locking compression plate-rod constructs in an in vitro fracture gap model. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2015; 28: 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chao P, Conrad B, Daniel DD, et al. Effect of plate working length on plate stiffness and cyclic fatigue life in a cadaveric femoral fracture gap model stabilized with a 12-hole 2.4 mm locking compression plate. BMC Vet Res 2013; 9: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muir P, Johnson KA, Markel MD. Area moment of inertia for comparison of implant cross-sectional geometry and bending stiffness. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 1995; 3: 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hurt R, Syrcle J, Elder S, et al. A biomechanical comparison of unilateral and bilateral String-of-Pearls locking plates in a canine distal humeral metaphyseal gap model. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2014; 27: 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hutcheson KD, Butler JR, Elder SE. Comparison of double locking plate constructs with single non-locking plate constructs in single cycle to failure in bending and torsion. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2015; 28: 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marcellin-Little DJ. Fracture treatment with circular external fixation. Vet Clin Small Anim Pract 1999; 29: 1153–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fruchter AM, Holmberg DL. Mechanical analysis of the veterinary cuttable plate. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 1991; 4: 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stiffler KS. Internal fracture fixation. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2004; 19: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sumner-Smith G. Non-union of fractures. In: Sumner-Smith G. (ed). Bone in clinical orthopedics. 2nd ed. Duebendorf: AO Publishing, 2002, pp 349–378. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Feline musculoskeletal pain index questionnaire

Raw data