Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of the present study was to describe histologically the gastro-oesophageal junction in the cat and interrelationships of this region. Our hypothesis was that cats are devoid of abdominal oesophagus.

Methods

Three centimetres of the terminal oesophagus, the phreno-oesophageal membrane with 1–2 cm margins of the diaphragmatic crural muscle and the proximal 3 cm of the gastric cardia were obtained from nine domestic shorthair cats and one domestic longhair cat that were euthanased for reasons other than digestive tract pathology. Longitudinal samples were examined histologically. Evaluated parameters included the location of the phreno-oesophageal membrane with reference to the transition between the oesophageal and gastric mucosa, the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle of the muscular layer of the distal oesophagus at points 3 mm and 6 mm cranial to the mucosa transition, and the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer at the mucosa transition level. Median differences in the thickness of the smooth muscle layer were compared by performing non-parametric statistical analysis using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results

The transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa was abrupt and corresponded to the point of insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane at the diaphragm level in all cats. The mean thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer at the point of oesophageal to gastric mucosa transition was significantly greater than the mean thickness of the oesophageal circumferential smooth muscle layer at 3 mm and 6 mm cranial to the mucosa transition (P ⩽0.05). The increased muscle thickness at the gastro-oesophageal junction correlates with the accepted location of the high-pressure zone, reflecting the caudal oesophageal sphincter. It seems that the whole oesophagus was situated within the thoracic rather than the abdominal cavity.

Conclusions and relevance

No distinct abdominal oesophagus was observed in nine domestic shorthair cats and one domestic longhair cat. These findings might have implications for the pathophysiology of hiatal hernia in cats.

Introduction

The gastro-oesophageal junction, the region where the oesophagus joins with the stomach, plays an important role in the pathophysiology of hiatal hernia and associated gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in cats and dogs.1–5 It is hypothesised that this junction is normally located caudal to the diaphragm where a short part of the oesophagus is situated within the abdominal cavity.2–4 The topographical anatomy of the gastro-oesophageal junction has been described in the cat, but little attention has been given to the presence of the abdominal oesophagus.6–8 Although many authors refer to the presence of abdominal oesophagus in cats, there is no clear evidence about the existence of a distinct abdominal oesophagus in this species.7,8 In certain canine breeds, including Beagles and Anatolian Shepherd Dogs, it has been shown that there is no distinct abdominal oesophagus.9,10 The aim of the present study was to describe histologically the gastro-oesophageal junction in the cat and interrelationships of this region. Our hypothesis was that cats are devoid of abdominal oesophagus.

Materials and methods

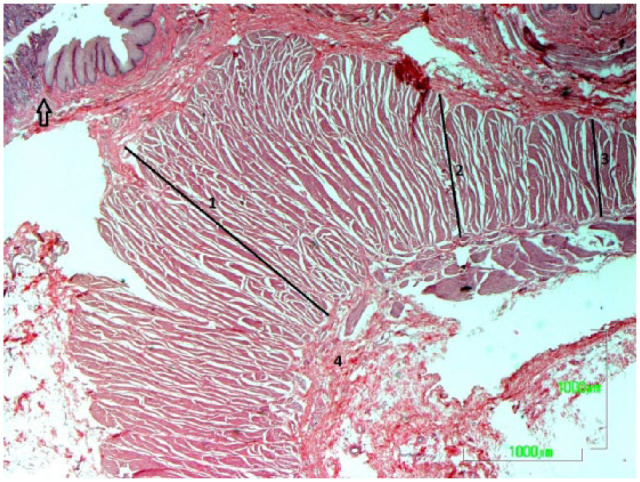

Tissues were taken from 10 cats that were euthanased for reasons other than digestive tract pathology. Nine domestic shorthair cats and one domestic longhair cat, six females and four males, with a median age of 2.5 years (range 0.25–16.5 years) and a median weight of 2 kg (range 0.5–4.5 kg) were used in this study. From each cat 3 cm of the distal oesophagus, the phreno-oesophageal membrane along with 1–2 cm margins of the diaphragmatic crural muscle and the proximal 3 cm of the gastric cardia were obtained. Longitudinal sections from each specimen incorporating distal oesophagus, phreno-oesophageal membrane and gastric cardia were prepared, embedded into paraffin wax and cut into 10 μm-thick sections for slide mounting, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. All slides were examined by direct light using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. Sections were assessed using a computer image analysis program (Image Pro Plus 6.3; Media Cybernetics) attached to a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. Parameters evaluated included the location of the phreno-oesophageal membrane with reference to the transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa, the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle of the muscular layer of the distal oesophagus at points 3 mm and 6 mm cranial to the mucosa transition, and the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer at the mucosa transition level (Figure 1). The histology of the gastro-oesophageal junction, as detected and evaluated in these sections, was compared with other studies. 8

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of the feline gastro-oesophageal junction. The phreno-oesophageal membrane (4) with reference to the transition of the oesophageal to the gastric mucosa (arrow), the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle of the muscularis layer of the distal oesophagus at a point 3 mm (3) and 6 mm (2) cranial to the mucosal transition and the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer at the mucosal transition level (1) are visualised (haematoxylin and eosin stain)

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed using statistical software (SPSS version 19.0). Data are expressed as median (range). A non-parametric statistical analysis using the Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to compare differences in the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer of the oesophagus between certain points. P ⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Results

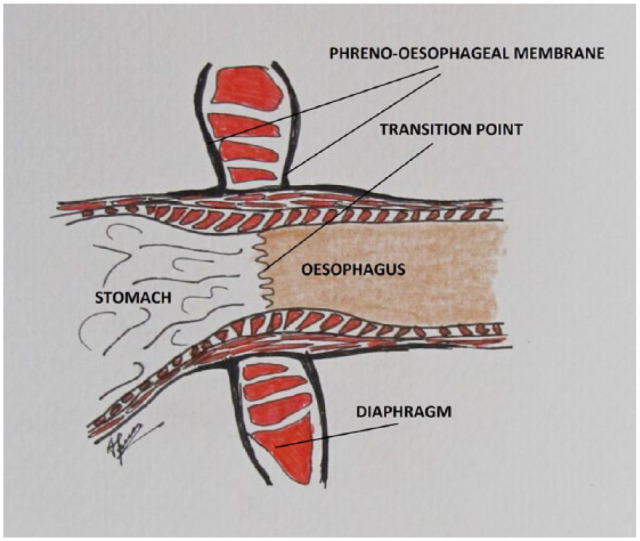

Histological examination of the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction showed that the muscular wall of the oesophagus was composed of only smooth muscle fibres arranged in two layers. The outer layer contained only longitudinal smooth muscle fibres and the inner layer contained only circular smooth muscle fibres. No glands were visible at the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. The transition of the oesophageal to the gastric mucosa was sudden and corresponded to the point of insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane between the bifurcation of the ascending and descending limbs of the membrane in all cats, suggesting that the transition from oesophageal to gastric mucosa took place at the diaphragm level. The median thickness (2001.25 μm; range 2499.46–1656.61 μm) of the circumferential smooth muscle layer at the point of oesophageal to gastric mucosa transition (gastro-oesophageal junction) was significantly greater than the median thickness of the oesophageal circumferential smooth muscle layer at 3 mm cranial to the mucosa transition (917.805 μm; range 1770.21–782.41 μm) and the median thickness (759.58 μm; range 1170.18–656.74 μm) of the oesophageal circumferential smooth muscle layer at 6 mm cranial to the mucosa transition (P ⩽0.05). The median distance between the cranial and caudal point of insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane was 4.85 mm (range 3.7–5.3 mm) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the feline gastro-oesophageal junction. The transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa is located at the level of the diaphragm and insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane. The oesophagus seems to be located within the thoracic cavity

Thickness data of the circumferential smooth muscle of the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction in 10 cats are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurements of the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle of the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction in 10 cats

| Cat number | Circumferential smooth muscle thickness of the distal oesophagus 6 mm cranial to the mucosal transition point (μm) | Circumferential muscle thickness of the distal oesophagus 3 mm cranial to the mucosal transition point (μm) | Circumferential muscle thickness of the gastro-oesophageal junction at the mucosal transition level (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 705.93 | 793.74 | 2499.46 |

| 2 | 656.74 | 782.41 | 1818.06 |

| 3 | 743.58 | 932.43 | 2191.94 |

| 4 | 714.01 | 815.33 | 2289.38 |

| 5 | 820.67 | 1359.81 | 1698.38 |

| 6 | 748.62 | 1325.75 | 1657.49 |

| 7 | 1170.18 | 1549.33 | 2147.42 |

| 8 | 1147.31 | 1770.21 | 2253.46 |

| 9 | 853.45 | 903.18 | 1656.61 |

| 10 | 770.54 | 898.71 | 1855.08 |

Discussion

According to some authors the feline gastro-oesophageal junction consists of the distal oesophagus, which continuing caudally joins with the gastric cardia, as a short abdominal part, after passing through the oesophageal hiatus of the diaphragm.7,11,12 The phreno-oesophageal membrane, comprising an ascending and a descending limb, anchors the distal oesophagus to the diaphragmatic crus. The attachment of the descending limb of the phreno-oesophageal membrane to the stomach is immediately caudal to the gastro-oesophageal junction. 8

The distal oesophageal muscular layer is composed of circular and longitudinal smooth muscle fibres. The distal oesophageal mucosa is covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which becomes simple columnar at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Microscopically the transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa was abrupt and located at the level of the diaphragmatic muscle cranial to the cardia and between the two layers of the phreno-oesophageal membrane.6,8

In the present study, in order to determine the gradual thickening of the circumferential smooth muscle layer from the distal oesophagus to the point of transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa, measurements of the thickness of the circumferential smooth muscle layer were performed at three points, 3 mm and 6 mm cranial to the mucosa transition at the oesophageal site and at the mucosa transition level.9,10

Our findings showed that there was a gradual thickening of the circumferential smooth muscle layer going towards the gastro-oesophageal junction starting from 759.58 μm 6 mm from the junction at the oesophageal site and ending at 2001.25 μm at the junction level. Our results compare favourably with those of others in cats where the mean muscle thickness of the distal oesophagus at 0.5 cm from the gastro-oesophageal junction was greater than that of the gastric side. 8 However, no statistical analysis of the muscular thickness was performed by the authors of this study to validate their results. Our findings also support recent studies in dogs where a consistent, significant increase in the muscle thickness at the level of the gastro-oesophageal junction was found.9,10 Based on the findings of the study presented here it seems that our cats have an increased muscle thickness at the gastro-oesophageal junction, which correlates with the accepted location of the high-pressure zone reflecting the anatomically ill-defined caudal oesophageal sphincter. 13

In the present study we found that the transition of the oesophageal to gastric mucosa was located at the level of insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane and between the bifurcation of the ascending and descending limbs of the membrane in all cats. Our findings are in agreement with others, who have reported that in cats the zone of mucosa transition is located at the level of the diaphragm and phreno-oesophageal membrane bifurcation. 8 In contrast, other authors reported the presence of a well-defined abdominal oesophagus in this species. 7 Additionally, studies in dogs demonstrated that the position of the cranial and caudal points of insertion of the phreno-oesophageal membrane at the level of the mucosa transition point was highly variable and breed dependent. 9 In our study, all cats shared similar histological findings showing a stable point of the mucosa transition being between the two limbs of the gastro-oesophageal membrane and reflecting the absence of an abdominal part of the oesophagus.

Some authors believe that in cats and dogs the caudal oesophageal sphincter and gastro-oesophageal junction are normally located within the abdominal cavity and control the passage of the contents between the oesophagus and stomach. 14 It is also reported that elevated intra-abdominal pressure generated by the abdominal portion of the oesophagus functions as a ‘flutter valve’, preventing the creation of gastro-oesophageal reflux.15,16 Displacement of the gastro-oesophageal junction into the thoracic cavity in the case of a sliding hiatal hernia deprives the cat of the ‘flutter valve’. However, it is also hypothesised that other extrinsic factors, including the right diaphragmatic crura, gastric cardia, gastro-oesophageal angle, the phreno-oesophageal membrane or the muscular sling of the lesser gastric curvature, may influence the moderation of gastro-oesophageal reflux in both cats and dogs.15,17

Limitations of the present study include the small number of relatively thin cats examined belonging to a certain breed. Our study has yielded some preliminary findings that need to be treated with caution.

Conclusions

Histological examination of the gastro-oesophageal junction in nine domestic shorthair cats and one domestic longhair cat showed that the whole oesophagus was located in the thoracic cavity, terminating at the level of the diaphragm. It seems that the cats examined in our study were lacking an abdominal oesophagus, which might alter our beliefs about the pathophysiology of hiatal hernia in this particular species. These results need to be confirmed by a larger study in several feline breeds.

Footnotes

Author note: Presented in the 25th Annual Scientific Meeting, European College of Veterinary Surgeons, Lisbon, 2016.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Accepted: 3 April 2017

References

- 1. Bright RM, Sackman JE, DeNovo C, et al. Hiatal hernia in the dog and cat: a retrospective study of 16 cases. J Small Anim Pract 1990; 31: 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ellison GW, Lewis DD, Phillips L, et al. Esophageal hiatal hernia in small animals: literature review and a modified surgical technique. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1987; 23: 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prymak C, Saunders HM, Wahabau RJ. Hiatal hernia repair by restoration and stabilization of normal anatomy. An evaluation in four dogs and one cat. Vet Surg 1989; 18: 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Waldron DR, Moon M, Leib MS, et al. Oesophageal hiatal hernia in two cats. J Small Anim Pract 1990; 31: 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lorinson D, Bright RM. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical treatment of hiatal hernias in dogs and cats: 27 cases (1978–1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Botha MGS. Note on the comparative anatomy of the cardio-oesophageal junction. Acta Anat 1958; 34: 52–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friedland GW, Kohatsu S, Lewin K. Comparative anatomy of feline and canine sling fibers. Analogy to human anatomy. Dig Dis 1971; 16: 495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bremner CG, Shorter RG, Ellis FH. Anatomy of feline esophagus with special reference to its muscular wall and phrenoesophageal membrane. J Surg Res 1970; 10: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pratscke KM, Fitzpatrick E, Campion D, et al. Topography of the gastro-oesophageal junction in the dog revisited: possible clinical implications. Res Vet Sci 2004; 76: 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alsafy MAM, El-Gendy SAA. Gastroesophageal junction of Anatolian Shepherd Dog; a study by topographical anatomy, scanning electron and light microscopy. Vet Res Commun 2012; 36: 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crouch JE. Text-atlas of cat anatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1969, p 145. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnes JA. Digestive system. In: Hudson LC, Hamilton WP. (eds). Atlas of feline anatomy for veterinarians. 2nd ed. Jackson, FL: Teton NewMedia, 2010, pp 154–170. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hashim MA, Waterman AF. Determination of the length and position of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) by correlation of external measurements with combined radiographic and manometric estimation in the cat. Br Vet J 1992; 148: 435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waldron DR, Leib MS. Hiatal hernia. In: Bojrab MJ. (ed). Disease mechanisms in small animal surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger, 1993, pp 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hunt GB. Hiatal hernia. In: Bojrab MJ, Monnet E. (eds). Mechanisms of disease in small animal surgery. 3rd ed. Jackson, FL: Teton New Media, 2010, pp 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornell K. Stomach. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA. (eds). Veterinary surgery small animals. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp 1500–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sivacolundhu RK, Read RA, Marchevsky AM. Hiatal hernia controversies – a review of pathophysiology and treatment options. Aust Vet J 2002; 80: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]