Abstract

Objective

Transference is a psychological process where feelings and attitudes towards a familiar person are unconsciously redirected to another. This phenomenon can be activated by physical resemblance, including facial features. Despite its potential therapeutic significance, little research has investigated transference processes in individuals with psychiatric conditions. Here, we explored how patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD)—characterized, among other features, by unstable relationships, self-damaging impulsivity, and suicidal ideation—would exhibit transference of negative and positive attributes.

Method

We performed an experiment where BPD participants and a control group with no prior psychiatric history completed a face-rating task. The task involved an evaluation of images of strangers who resembled significant others in terms of facial features.

Results

Our results indicated that transference effects were elicited in both groups. Notably, there were significant differences in ratings assigned to significant others, whereby participants with BPD displayed transference of negative attributes more and positive attributes less intensely than healthy controls, which, in part, correlated with attachment anxiety.

Conclusions

Our findings align with the tendency in BPD to perceive interpersonal relationships and emotions more negatively. They have potential implications for psychotherapeutic approaches in treating patients with BPD and our understanding of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of BPD itself.

Keywords: transference, transference processes, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), Face-Rating Task, attachment anxiety

Introduction

The concept of transference has long been recognized as a psychological process that is ubiquitous in human interaction and is most notably observed in psychotherapy. The term is generally associated with the work of Sigmund Freud who introduced transference to describe the redirection of emotions associated with the therapeutic relationship (Freud, 1912). Today, transference is understood as a general phenomenon that encompasses unconscious redirections of emotions also outside a therapeutic context (Chen & Andersen, 1999; K. N. Levy & Scala, 2012), “in which aspects of important and formative relationships (such as with parents and siblings) are unconsciously ascribed to unrelated current relationships” (Levy, 2009, p. 191). Transference is acknowledged as a non-pathological psychological phenomenon, although transference can be dysfunctional in relation to unresolved conflict and thus lead to maladaptive behavior and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. It is understood as a dynamic process which can vary significantly in intensity and between individuals. Transference can also be utilized in therapy as a means to understand the nature of past and present social relationships (Andersen & Przybylinski, 2012; Greenson, 1965). Clearly, transference is linked to personality traits and previous experiences, particularly ones with early caregivers (K. N. Levy & Scala, 2012).

The distinction between positive and negative transference is essential, as it may shed light on how individuals who seek psychotherapy perceive and respond to interpersonal stimuli. Positive transference, which involves projecting positive feelings and attributes onto others, has been associated with more positive therapeutic outcomes and better social functioning (Auchincloss & Samberg, 2012, p. 268). In contrast, negative transference may lead to maladaptive behavior and difficulties in interpersonal relationships, especially when combined with intense emotional reactions (Auchincloss & Samberg, 2012, p. 268; Cabaniss et al., 2016, p. 237). As negative transference may particularly emerge before a background of childhood adversity, we were specifically interested in exploring transference in individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

BPD is the most prevalent personality disorder (Grant et al., 2008; Torgersen et al., 2001), characterized, among other features, by a profound ambivalence in close interpersonal relationships, difficulties in maintaining trustful (therapeutic) alliances, and frequent projections of negative self-images on others, as well as projective identification, a psychological process where an individual unconsciously projects their own negative feelings and self-images onto another person, often leading to a distorted perception of the other’s behavior. (Leichsenring et al., 2011; Lieb et al., 2004). A large proportion of patients with BPD have experienced childhood abuse or neglect (Silk et al., 2005), which predictably impacts on the intensity and quality of transference. Specifically, negative transference may contribute to the chronic and pervasive interpersonal difficulties observed in BPD. Improving the understanding of the mechanisms underlying both positive and negative transference in individuals with BPD may therefore help improve their treatment and overall functioning.

Transference can be operationalized in the laboratory by presenting subtle memory cues that implicitly remind participants of significant others during an encounter with a previously unknown person. In a pioneering study, transference effects were induced based on physical appearance, i.e. by presenting previously unseen faces with features subtly resembling those of significant others (Kraus & Chen, 2010). Participants were asked for information about a significant other, such as to rate the positivity of their relationship and to name attributes accurately describing their significant other. Furthermore, participants rated their hypothesized self-concept, i.e. by imagining how they would feel if they would interact with the depicted person. This was followed by a face-rating task, in which participants rated how much presented faces from a public face database resembled their significant other. In a subsequent session, participants were confronted with photographs of faces, including faces previously described as highly resembling their significant other, and asked about how likeable they found the depicted persons and how accurate they thought attributes they previously used to describe their significant other and their relationship, fit the shown person. Of note, at this stage, participants were oblivious to the aim of the study. In the study by Kraus and Chen (2010) and in a replication pilot study in our lab (Chang, 2017) facial-feature resemblance of significant others elicited a transference reaction. That is, participants rated faces previously described as resembling their significant others on average as more positive. Importantly, however, participants showed no indication on various measures of explicit memory that they explicitly recognized any obvious resemblance between the photographs of the previously unknown persons and their significant others. Furthermore, the authors observed a strong agreement between a rating of their self-concept in a hypothesized interaction with the shown person and the self-concept participants experience when interacting with the respective significant other. This indicated that transference not only pertains to external attributes of others, but that it can reactivate parts of internalized relationships. While negative attributes were also included in the study published by Kraus and Chen (2010), acquired data were analyzed by comparing mean ratings of attributes describing their significant other in total with no difference made between positive and negative descriptors, such that it remains unclear whether or not negative transference occurred. Notably, the aforementioned studies included psychologically healthy participants, mainly undergraduate students (Kraus & Chen, 2010; Chang, 2017).

To the best of our knowledge, no study has explored such transference effects in patients with BPD. We hypothesized that individuals with BPD would be significantly more likely to engage in transference of negative attributes to individuals who resemble significant others that putatively played a role in childhood experiences. We especially expected participants with BPD to exhibit a significantly different interaction in a transference setting depending on whether a positive or negative attribute was being transferred (representing positive and negative transference, respectively) in comparison to healthy controls, i.e. a more intense negative transference, as well as a less intense positive transference effect in patients with BPD.

Methods

Twenty-four participants diagnosed with BPD according to DSM-5 criteria were recruited from an inpatient ward of the LWL University Hospital Bochum, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany. Participants had a verified diagnosis of a borderline personality disorder according to a standardized interview. They were additionally required to fill out the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23) as a measure of borderline symptom severity (Wolf et al., 2009). The average score was 52.8 (SD +/- 16.5; range: 13-81), suggesting moderate to high illness severity. In addition, we recruited a group of 24 healthy subjects without a previous history of psychiatric conditions as a control group. The groups were matched for gender and age. In total, 44 females and 6 males were recruited with a mean age of 25.1 years (SD +/- 3.5; range: 18-30 years). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Ruhr University Bochum, Germany (registration number 17-6283).

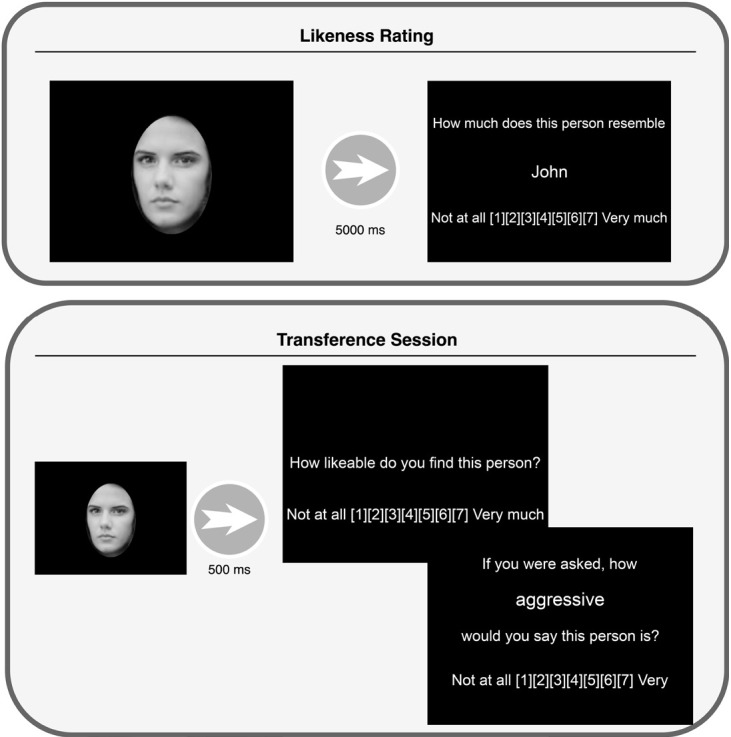

All participants were asked to select three significant persons in their lives whom they have had a close relationship with since their childhood or adolescence. They were then asked to fill out a questionnaire for each person, in which they reported some details such as length and the nature of the relationship (i.e. sibling, parent, close friend). In addition, subjects had to rate their significant others by how much they liked them in general and were also asked to write down attributes or character traits that would best describe the person in categories of positive, negative, as well as irrelevant attributes that did not fit the person they were describing (Kraus & Chen, 2010). Subjects were afterwards invited to participate in the actual experiment, which took part at the LWL University Hospital Bochum, Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany. The experiment itself consisted of two separate sessions, which were carried out on the same day. Subjects started the first session (subsequently termed ‘likeness session’) with a rating of unknown faces, presented on a computer screen, on a Likert point scale from 1 (no resemblance) to 7 (high resemblance) with a significant other (figure 1, top). In total, 200 representative random faces from a standardized image collection with a neutral facial expression were presented to each test subject (Hond & Spacek, 1997; Spacek, & Libor, 2009). After the first session, participants had a short break before continuing with the second part, during which they were asked to fill out a validated German version of the of the Experiences in Close Relationships questionnaire, a widely-used tool to assess attachment-style with regard to anxiety and avoidance in close relationships (Brennan et al., 1998; Neumann et al., 2007). While subjects completed rating the resemblance of faces in the first session, the second session (‘transference session’) of the experiment was prepared in the background. This consisted of a customized experiment on a computer, where a set of randomized faces composed of faces of humans rated by the subject as closely resembling one of the given significant others (Resemblance Condition or “R”) and faces explicitly previously rated by the subjects to not resemble their significant others (Resemblance Control Condition or “RC”) were shown for 500 milliseconds each (figure 1, bottom). Subjects were subsequently asked to imagine being in a social setting interacting with the person the face belonged to (for the test group, this social setting would be a group therapy session, for the control group a university seminar). Subjects were then asked how accurate the presented attributes were in describing the depicted person on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Attribute categories consisted of a general agreeableness category as well as positive, negative and irrelevant attributes. For this part, attributes were previously extracted from the questionnaires the subjects had filled out regarding their significant others.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study design, with the first session consisting of the likeness rating, and the second session utilizing the first session’s results to try to elicit a transference reaction

Test sessions were conducted using openSesame, an open source framework for experimental testing in psychology (Mathôt et al., 2012), with the experiment itself having been programmed in the Python programming language (Van Rossum & Drake, 2009). The collected study data was analyzed using R, an open source programming language and suite for statistical analysis, and visualized using ggplot2 and ggstatsplot, which are both libraries for data visualization (R Core Team, 2022; RStudio Team, 2019; Wickham, 2016; Patil, 2021).

To assess whether transference effects were elicited in the categories we were interested in, we first tested for a significant effect when comparing the two experimental conditions, one where we expected a transference effect to occur due to subjective resemblance according to the rating (“R”) and a control condition that should not cause any transference effect to occur, where the face displayed would be one that was rated as not looking subjectively similar to the subjects’ given significant other (“RC”). We then conducted a mixed ANOVA to look for an interaction effect between the two tested groups (patients with BPD and healthy subjects with no prior history of any psychiatric illness) and, as within-subject factors, the valence of the attribute (positive or negative) that was presented to subjects during the experimental session as well as the condition (R or RC). For analysis, we compared the mean raw response rating given by participants for each of the categories positive and negative attribute and conditions R and RC. The shown attributes were previously indicated by participants in the questionnaire as highest-ranking positive and negative attribute of a significant other.

We also used attributes irrelevant to the presented significant other as a distractor category. For this, we measured the mean raw response value given in the second session regarding the shown face and the initially given highest-ranked irrelevant attribute in the questionnaire regarding the significant other whose resembling face was shown. Because subjects were asked to name an attribute that in their opinion was not descriptive of their significant other in any way, we did not expect any transference effects to occur within this attribute category.

Results

“Significant Others”

Significant others named by participants were mostly the mother (n = 40), a close friend (n = 26) or a sibling (n =22). While in both groups the mother was the most frequently named significant other, the father was less often named in the BPD group compared to the control group. In turn, BPD participants more often included friends than their control counterparts (table 1).

Table 1.

Occurrences of kinds of relationships with significant others named by participants of the bpd and control group

| bpd | control | |

|---|---|---|

| Mother | 19 | 21 |

| Father | 6 | 14 |

| Sibling | 10 | 12 |

| Partner | 6 | 8 |

| Relatives | 6 | 6 |

| Other | 25 | 11 |

When asked about how positive they would rate their given relationships when thinking about the positive aspects on a 7-point Likert scale, the BPD group rated their relationships as significantly less positive (M = 5.51; SD = 1.59) than the control group (M = 6.43; SD = 0.73). (t(96) = [4.4]; p < .0001)

We also asked participants to rate their relationships with regard to aspects they considered negative. Interestingly, participants with BPD rated their relationships significantly less negative on average (M = 3.97; SD = 1.96) than their control counterparts (M = 4.67; SD = 1.4). (t(129) = [2.45]; p = .016)

Rating Performance

For our main analysis, we applied a mixed ANOVA design with the two tested groups BPD and control as the between-subject factor, and the attribute category presented (positive or negative) as a within-subject factor, with a second within-subject factor being “condition” (R vs. RC). The three-way interaction model approached significance (F(1, 46) = [3.33]; p = .074). A significant main effect was found for “condition”, indicating successful transference (F(1, 46) = [16.94]; p < .001). Another main effect occurred for the attribute category, with negative attributes being rated significantly lower than positive ones (F(1, 46) = [11.33]; p = .002), indicating that regardless of the shown condition participants in both groups rated negative attributes as less fitting than positive ones. We also found an interaction between “group” and “category”, supporting our main hypothesis of a difference in the rating between patients with BPD and healthy control subjects when asked about positive or negative attributes (F(1, 46) = [13.19]; p < .001). Another significant interaction effect was found between “condition” and “category” (F(1, 46) = [4.99]; p = .03), indicating that both healthy controls and bpd participants attributed positive and negative attributes differently to faces that did vs. did not resemble their significant others. These results show that transference was effective and modulated by emotional category across groups.

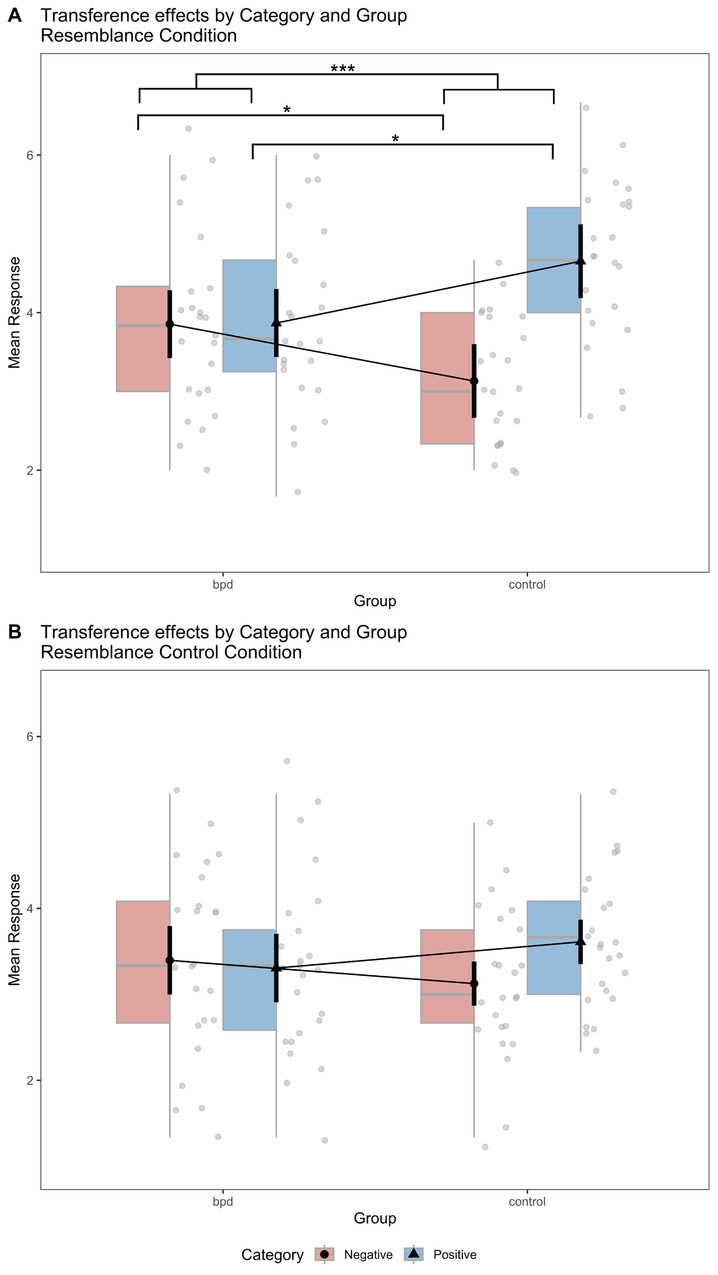

Even though the three-way ANOVA just failed to reach statistical significance, we further explored the R and RC conditions separately, according to our main research question whether transference effects differ between patients and controls (figure 3). Having shown in the previous analysis that transference effects occur across groups (i.e., showing a difference between R and RC conditions), we particularly focused on the analysis of the R condition, since this comparison captures the central aspect of our hypotheses, i.e. whether transference effects differ between groups with respect to emotional categories. In the R condition, a significant interaction occurred between “group” and “category” (F(1, 46) = [12.01]; p < .001; figure 3 (A)). A pairwise comparison for each attribute category showed that there was a significant difference between the BPD group and the control group when presenting SO-resembling faces with a negative attribute, suggesting that BPD subjects perceived SO-resembling faces as more negative than healthy controls (t(41) = [2.5]; p = .017; figure 3 (A)). A significant difference was also observed when presenting the BPD group and the control group faces resembling significant others (SO) with a positive attribute, suggesting that BPD subjects rated SO-resembling faces less positive than controls (t(46) = [2.5]; p = .016; figure 3 (A)). In the RC condition, the interaction effect was weaker and did not reach significance (F(1, 46) = [3.15]; p = .08; figure 3 (B)). A pairwise comparison for each attribute category in the RC condition showed no significant difference between the BPD group and (t(44) = [0.92]; p = .359; figure 3 (B)). A difference for positive attributes was also absent (t(42) = [1.12]; p = .268; figure 3 (B)).

Figure 3.

Results of the second session grouped by category of attribute asked; “control” being the group of healthy test subjects, “bpd” being the BPD patient group

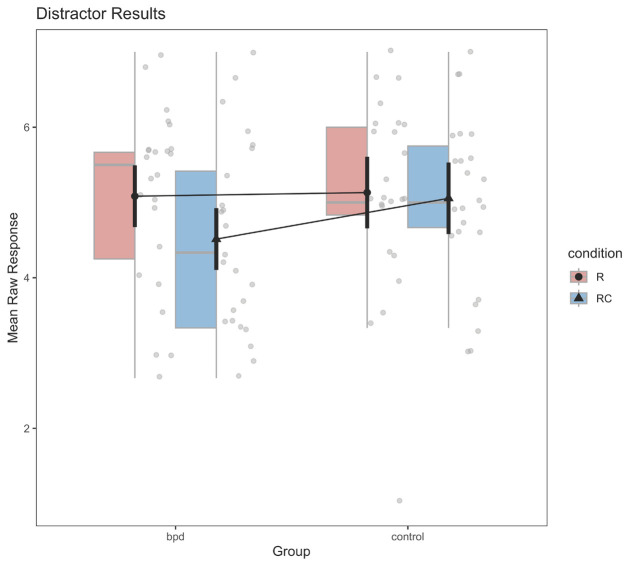

We finally performed an ANOVA for the distractor category “irrelevant attribute” to better understand how participants reacted when confronted with an unrelated attribute (figure 4). As expected, we did not see any main effect for the group (F(1, 46) = [1,13]; p = .292) or the condition presented (F(1, 46) = [2,26]; p = .139). We also did not find an interaction effect (F(1, 46) = [1,32]; p = .257).

Figure 4.

Results of the distractor category (“irrelevant” attribute”); “control” being the group of healthy test subjects, “BPD” being the BPD patient group; “R” meaning resemblance condition, “RC” meaning resemblance

Attachment Style

The BPD group scored significantly higher on the ECR-R in terms of attachment anxiety than healthy controls (BPD: M = 5.2; SD = 0.96, control: M = 2.5; SD = 0.88; t(46) = [10.2]; p < .0001), as well as avoidance (BPD: M = 4.09; SD = 1.26, control: M = 2.32; SD = 0.74; t(37) = [5.9]; p < .0001).

Correlation Analyses

No correlation occurred between symptom severity (BSL-23) scores and any one of the resemblance ratings. Specifically, the correlations for positive attributes in the resemblance (r = -0.02; p = 0.926) and resemblance control condition (r = -0.189; p = 0.377), as well as the negative attributes in the resemblance (r = -0.215; p = 0.313) and resemblance control condition (r = -0.038; p = 0.859) were statistically not significant. Likewise, the distractor category did not show any significant correlation in either the resemblance (r = -0.134; p = 0.532) and resemblance control condition (r = -0.21; p = 0.326).

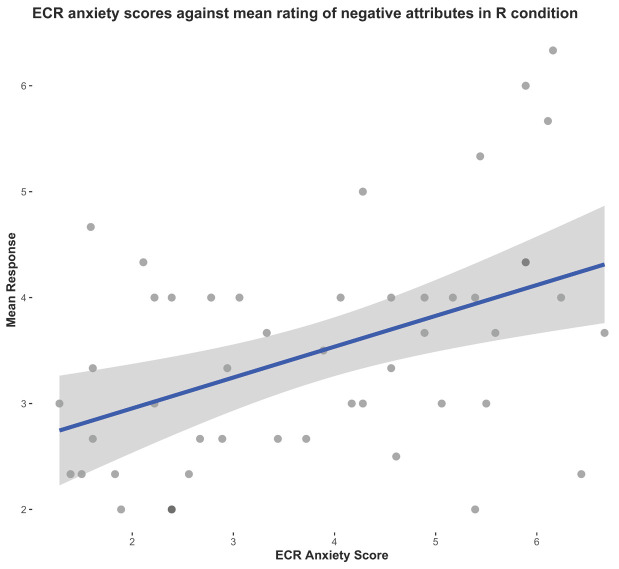

With regard to attachment, ECR anxiety scores correlated significantly with the rating of negative attributes (rho = 0.414; p = 0.003; figure 2). Moreover, the correlation of attachment anxiety with the rating of positive attributes in the resemblance condition approached significance (rho = -0.257; p = 0.078). All other correlation of attachment anxiety with ratings were non-significant (all p > .05).

Figure 2.

Correlation of ECR anxiety scores with given mean responses regarding a negative attribute in the R condition

Likewise, ECR avoidance scores did not correlate significantly with any one condition or attribute.

Discussion

The present study sought to explore the quality and intensity of transference-related processes in patients with BPD. Consistent with previous work (Kraus and Chen, 2010), transference was elicited in both the clinical BPD group and controls, indicated by participants more often rating attributes previously given for significant others as fitting for faces resembling them than for non-resembling faces. This finding was corroborated by the absence of transference in the distractor condition.

Interestingly from a psychodynamic point of view, we found differences in transference between BPD and controls, whereby individuals with BPD rated faces resembling their significant others as more negative and less positive than controls. This finding is compatible with previous research suggesting a skewed perception of emotional valence in individuals with BPD towards negativity, and may reflect a general tendency in BPD individuals to experience intense and fluctuating emotions as negative, particularly in interpersonal contexts (Winter et al., 2017; Salsman & Linehan, 2012; Coifman et al., 2012). This is in stark contrast to our finding that BPD patients stated that they experience their relationships as less negative than the healthy controls, pointing to a discrepancy between subjective experience and behavior. This would be in line with psychodynamic theorizing in that BPD patients use defense mechanisms in order to ward off negative experiences with others whereas they feel and act dramatically differently, which may explain their common interactional difficulties (Zanarini et al., 2013). Interestingly, we found a significant correlation of attachment anxiety with negative rating of significant-other resembling individuals, which could corroborate the interpretation that transference processes differ between securely and insecurely attached individuals.

Furthermore, positive transference was more pronounced in the control group compared to BPD, suggesting that relational experiences in individuals with BPD are not limited to an overemphasis of negative attributions. The same pattern of results emerged in our pilot study with a small student sample (n = 16) using the same paradigm, where also only positive, but not negative attributes elicited a transference effect. This suggests that healthy participants tend to perceive others in more positive ways, which could arguably be linked to more positive experiences with significant others in their biographical history.

Previous research has shown that individuals with BPD show a negativity bias towards faces with neutral facial expressions (Dyck et al., 2009; Vestergaard et al., 2020). Indeed, individuals with BPD often tend to interpret faces with neutral expressions as negative (Dyck et al., 2009). Although this approach differs from our own, it is entirely consistent with our findings.

The examination of transference effects based on visual cues in clinical samples such as patients with BPD underscores the importance of a reevaluation of our understanding of psychotherapeutic settings. In fact, transference is an integral part of any psychotherapy, which involves a complex interplay of psychological and perceptual factors. That is, psychotherapy cannot be viewed simply as verbal exchange between therapist and patient that is independent of prior interpersonal experiences of both interlocutors (Høglend, 2014). Instead, research has shown that the physical appearance of the therapist, including gender and age, may significantly affect the therapeutic alliance and outcome (Harris & Busby, 1998; Behn et al., 2018). In support of this perspective, our study findings imply a need for the therapist to understand possible transference effects that can be based on visual cues such as similarity to significant others of the patient.

A limitation of the study is the analysis of transference effects without a more nuanced look at the exact nature of the relationship with the participants’ significant other. Arguably, transference of maternal characteristics may substantially differ from transference effects elicited by recalled features of a partner or a friend. Additional research is thus warranted to improve our understanding of positive and negative transference in patients with BPD, depending on early experiences with caregivers and with regard to more nuanced and complex modern conceptions of transference as discussed in contemporary psychoanalysis (e.g., Ferro and Civitarese, 2015). This seems highly relevant for psychotherapeutic approaches, but would require an extension and replication in larger samples. In addition, transference can certainly not only be elicited by visual cues – in fact, auditory cues (voice pitch or intonation) or even olfactory stimuli may work as well. However, to the best of our knowledge, no research exists using stimuli other than visual ones or such based on written language for the examination of transference. Finally, we did not examine the participants’ current mood state, which may have affected the transference process in terms of intensity and categories in which transference was demonstrated.

Together, the present study indicates for the first time that individuals with BPD differ from psychologically unaffected people in the transference of attributes of significant others to unfamiliar individuals. Remarkably, this process can be evoked by facial resemblance, while not being restricted to the visual realm. Overall, people with BPD seem to see significant others as more negative and less positive, and this bias is apparently transferred to subjects who resemble close others physically. If confirmed, we expect that these findings may have substantial impact on clinical research and practice, including psychological treatment of individuals BPD, independent of the psychotherapeutic “school”.

References

- Andersen, S. M., & Przybylinski, E. (2012). Experiments on transference in interpersonal relations: Implications for treatment. Psychotherapy, 49, 370–383. 10.1037/a0029116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss, E. L., & Samberg, E. (2012). Psychoanalytic Terms and Concepts. Yale University Press; JSTOR. 10.2307/j.ctv6jm9bp [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behn, A., Davanzo, A., & Errázuriz, P. (2018). Client and therapist match on gender, age, and income: Does match within the therapeutic dyad predict early growth in the therapeutic alliance? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(9), 1403–1421. 10.1002/jclp.22616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. Attachment Theory and Close Relationships, 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cabaniss, D. L., Cherry, S., Douglas, C. J., & Schwartz, A. (2016). Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: A Clinical Manual Second Edition (1st ed.). Wiley. 10.1002/9781119142010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. Y. (2017). Shadows from the Past: A Paradigm for Neuroimaging Study of Transference Processes [Master’s Thesis]. Ruhr-University Bochum. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Andersen, S. M. (1999). Relationships from the Past in the Present: Significant-Other Representations and Transference in Interpersonal Life. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 31, pp. 123–190). Elsevier. 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60273-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coifman, K. G., Berenson, K. R., Rafaeli, E., & Downey, G. (2012). From negative to positive and back again: Polarized affective and relational experience in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(3), 668–679. 10.1037/a0028502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck, M., Habel, U., Slodczyk, J., Schlummer, J., Backes, V., Schneider, F., & Reske, M. (2009). Negative bias in fast emotion discrimination in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 39(5), 855–864. 10.1017/S0033291708004273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, A., & Civitarese, G. (2015). The analytic field and its transformations. Karnac Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. (1912). The dynamics of transference. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XII (1911-1913): The Case of Schreber, Papers on Technique and Other Works (pp. 97–108). [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B. F., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Huang, B., Stinson, F. S., Saha, T. D., Smith, S. M., Dawson, D. S., Pulay, A. J., Pickering, R. P., & Ruan, W. J. (2008). Prevalence, Correlates, Disability, and Comorbidity of DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder: Results From the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(4), 533–545. 10.4088/JCP.v69n0404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenson, R. R. (1965). The working alliance and the transference neurosis. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 34, 155–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S. M., & Busby, D. M. (1998). THERAPIST PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS: AN UNEXPLORED INFLUENCE ON CLIENT DISCLOSURE. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 24(2), 251–257. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1998.tb01081.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høglend, P. (2014). Exploration of the Patient-Therapist Relationship in Psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(10), 1056–1066. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14010121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hond, D., Spacek, L.. (1997). Distinctive Descriptions for Face Processing. Proceedings of the 8th British Machine Vision Conference BMVC97, Colchester, England, 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M. W., & Chen, S. (2010). Facial-Feature Resemblance Elicits the Transference Effect. Psychological Science, 21(4), 518–522. 10.1177/0956797610364949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring, F., Leibing, E., Kruse, J., New, A. S., & Leweke, F. (2011). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 377(9759), 74–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, K. (2009). Psychodynamic and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (pp. 179–211). [Google Scholar]

- Levy, K. N., & Scala, J. W. (2012). Transference, transference interpretations, and transference-focused psychotherapies. Psychotherapy, 49(3), 391–403. 10.1037/a0029371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 364(9432), 453–461. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathôt, S., Schreij, D., & Theeuwes, J. (2012). OpenSesame: An open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 314–324. 10.3758/s13428-011-0168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, E., Rohmann, E., & Bierhoff, H.-W. (2007). Entwicklung und Validierung von Skalen zur Erfassung von Vermeidung und Angst in Partnerschaften. Diagnostica, 53(1), 33–47. 10.1026/0012-1924.53.1.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil, I. (2021). Visualizations with statistical details: The “ggstatsplot” approach. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(61), 3167. 10.21105/joss.03167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. (2019). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, Inc. http://www.rstudio.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Salsman, N. L., & Linehan, M. M. (2012). An Investigation of the Relationships among Negative Affect, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation, and Features of Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34(2), 260–267. 10.1007/s10862-012-9275-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silk, K. R., Wolf, T. L., Ben-Ami, D. A., & Poortinga, E. W. (2005). Environmental Factors in the Etiology of Borderline Personality Disorder. In Borderline Personality Disorder (Mary C Zanarini) (p. 52). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Spacek, Libor, 2009. Facial Images Database. https://cmp.felk.cvut.cz/~spacelib/faces/

- Torgersen, S., Kringlen, E., & Cramer, V. (2001). The Prevalence of Personality Disorders in a Community Sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(6), 590. 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rossum, G., & Drake, F. L. (2009). Python 3 Reference Manual. CreateSpace. [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard, M., Kongerslev, M. T., Thomsen, M. S., Mathiesen, B. B., Harmer, C. J., Simonsen, E., & Miskowiak, K. W. (2020). Women With Borderline Personality Disorder Show Reduced Identification of Emotional Facial Expressions and a Heightened Negativity Bias. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(5), 677–698. 10.1521/pedi_2019_33_409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D., Bohus, M., & Lis, S. (2017). Understanding Negative Self-Evaluations in Borderline Personality Disorder—A Review of Self-Related Cognitions, Emotions, and Motives. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(3), 17. 10.1007/s11920-017-0771-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M., Limberger, M. F., Kleindienst, N., Stieglitz, R.-D., Domsalla, M., Philipsen, A., Steil, R., & Bohus, M. (2009). Kurzversion der Borderline-Symptom-Liste (BSL-23): Entwicklung und Überprüfung der psychometrischen Eigenschaften. PPmP - Psychotherapie · Psychosomatik · Medizinische Psychologie, 59(08), 321–324. 10.1055/s-0028-1104598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2013). Defense Mechanisms Reported by Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder and Axis II Comparison Subjects Over 16 Years of Prospective Follow-Up: Description and Prediction of Recovery. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(1), 111–120. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]