We investigated how weather, behaviour and disease influence core body temperature (Tb) of wild koalas in summer. We found that koalas are more heterothermic than previously recognized. Tb increased with ambient temperature and disease disrupted the 24-hr circadian pattern of Tb. Behaviour (i.e. tree hugging and drinking free water) was not effective in moderating Tb.

Keywords: Arboreal folivore, body heat, climate change, temperature regulation, temperature rhythmometry, thermal stress

Abstract

Thermoregulation is critical for endotherms living in hot, dry conditions, and maintaining optimal core body temperature (Tb) in a changing climate is an increasingly challenging task for mammals. Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) have evolved physiological and behavioural strategies to maintain homeostasis and regulate their Tb but are thought to be vulnerable to prolonged heat. We investigated how weather, behaviour and disease influence Tb for wild, free-living koalas during summer in north-west New South Wales. We matched Tb with daily behavioural observations in an ageing population where chlamydial disease is prevalent. Each individual koala had similar Tb rhythms (average Tb = 36.4 ± 0.05°C), but male koalas had higher Tb amplitude and more pronounced daily rhythm than females. Disease disrupted the 24-hr circadian pattern of Tb. Koala Tb increased with ambient temperature (Ta). On the hottest day of the study (maximum Ta = 40.8°C), we recorded the highest (Tb = 40.8°C) but also the lowest (Tb = 32.4°C) Tb ever documented for wild koalas, suggesting that they are more heterothermic than previously recognized. This requires individuals to predict days of extreme Ta from overnight and early morning conditions, adjusting Tb regulation accordingly, and it has never been reported before for koalas. The large diel amplitude and low minimum Tb observed suggest that koalas at our study site are energetically and nutritionally compromised, likely due to their age. Behaviour (i.e. tree hugging and drinking water) was not effective in moderating Tb. These results indicate that Ta and koala Tb are strongly interconnected and reinforce the importance of climate projections for predicting the future persistence of koalas throughout their current distribution. Global climate models forecast that dry, hot weather will continue to escalate and drought events will increase in frequency, duration and severity. This is likely to push koalas and other arboreal folivores towards their thermal limit.

Introduction

Ambient temperature (Ta) is one aspect of climate that can determine a species’ distribution via its impact on the energy and water requirements of thermoregulation. The Ta of terrestrial environments typically varies temporally so endothermic animals must thermoregulate to maintain core body temperature (Tb) within a suitable range (Bozinovic et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2019; Turner, 2020). Endothermic thermoregulation can be demanding in terms of energy and water requirements, and there is a range of tolerance for Ta within which a species can indefinitely maintain thermal homoeostasis (Withers, 1992). The impact of extreme weather events such as drought and heatwaves, exacerbated by climate change, challenges the ability of many species to maintain Tb within tolerable limits (Welbergen et al., 2008; McKechnie and Wolf, 2010). During these events, Ta may exceed not only the range of tolerance but even the zone of resistance, where the conditions cannot be withstood, and lead to mortality. Consequently, the distribution and abundance of vulnerable species with narrow thermal tolerances are predicted to decline, with serious conservation implications (Williams et al., 2003; Krockenberger et al., 2012; Freeman et al., 2018; de la Fuente and Williams, 2023).

Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) are nocturnal/crepuscular arboreal marsupial folivores endemic to Australia, with their geographical range dependent on distributions of Eucalyptus and Corymbia trees (Martin et al., 2008). They face a variety of threats (Charalambous and Narayan, 2020) and are listed as endangered in New South Wales (NSW), Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). The ongoing decline in distribution and abundance of koalas is compounded by the added pressures of climate-change-driven events such as heatwaves, droughts and bush fires (Reckless et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2021).

Koalas are homeothermic endotherms that regulate their Tb within a range of approximately 2.4°C around a mean of 36.3°C (Adam et al., 2016). Koalas have physiological and behavioural adaptations that enhance their tolerance of high Ta. For example, they have highly insulative fur and thermal windows, which facilitate heat exchange (Briscoe et al., 2015). They produce concentrated urine, conserving body water (Degabriele, 1980; Carlisle et al., 1989), they have low metabolic rates, minimizing energy requirements and heat production (Degabriele and Dawson, 1979), and they pant and lick their fur to facilitate evaporative cooling (Degabriele and Dawson, 1979; Ellis et al., 2010; Briscoe et al., 2014). Koalas seek cool microhabitats in hot weather (Crowther et al., 2014) and adopt tree-hugging postures that promote heat exchange (Briscoe et al., 2014). If available, they drink free water to facilitate enhanced evaporative cooling at high Ta (Mella et al., 2019).

Despite some tolerance of hot weather, koalas have low points of relative water economy (i.e. the ambient temperature at which metabolic water production balances evaporative water loss) compared to other marsupials, indicating a limited capacity to maintain water balance at high Ta (Cooper et al., 2020), and their increased salivation for enhanced evaporative heat loss is inefficient (Degabriele and Dawson, 1979). Koala’s folivorous diet is associated with a high intake of plant secondary metabolites (PSMs), which must be detoxified, leading to generation of excess metabolic heat (Beale et al., 2018). At high Ta, dissipation of this excess heat requires enhanced evaporative water loss, but as the majority of water intake in dry and hot weather comes from leaves, this results in even greater intake of PSM (Nagy and Martin, 1985). Consequently, Ta exceeding 37.7°C can lead to heat stress in koalas (Adams-Hosking et al., 2011) and death during periods of extended drought (Gordon et al., 1988; Clifton, 2010; Ellis et al., 2010; Lunney et al., 2012). After a temperature peak of 44.7°C in South Australia, koalas continued to suffer from thermal stress (evident through dehydration and high cortisol levels) even after temperature decreased to an average of 28.3°C (Narayan and Williams, 2016). Hence, koalas appear to be critically affected and less resilient to periods of extreme heat than other marsupials (Dawson and Hulbert, 1970; Maloney et al., 2004).

The energetic requirements of endothermic thermoregulation can impact on host–pathogen relationships and influence disease dynamics at the population level (Harvell et al., 2002). Hence, animals may have to trade off the demands of thermoregulatory and immune responses (Hawley et al., 2012). For example, in hot dry summers, koalas have reduced expression of adaptive immune genes and increased transcription of a stress pathway gene (Fernandez et al., 2024). Chlamydiosis, caused by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia pecorum, is the most significant disease in koala populations (Polkinghorne et al., 2013), causing ocular and urogenital disease. The resulting conjunctivitis may impede vision and affect koalas’ ability to climb and shelter in trees (Schmid et al., 1991), while urinary incontinence (Kollipara et al., 2012) contributes to excessive water loss (Brown and Grice, 1984; Canfield and Spencer, 1993), reducing the availability of water for evaporative cooling (Clifton et al., 2007). As seeking suitable microhabitat and evaporative cooling are two major ways koalas avoid heat stress (Degabriele and Dawson, 1979; Ellis et al., 2010), chlamydiosis could reduce the thermal tolerance of koalas, making them even more susceptible to heatwaves. However, the potential impact of disease on koala thermoregulation has not yet been established.

Understanding the factors affecting Tb is crucial for the conservation of thermally vulnerable species in the face of human-induced climate change (Fuller et al., 2010). Increased frequency and severity of heatwaves and drought are unavoidable consequences of global warming, so investigating how koala thermoregulation will be impacted is important for predicting population declines and evaluating future climatic distribution of this endangered species. Here, we assess how extreme heat impacts koala Tb in a population of wild, free-ranging koalas in north-west NSW, where chlamydiosis is prevalent. We quantify the effects of behavioural responses such as drinking and tree hugging on Tb and evaluate how koala health status may influence koalas’ ability to thermoregulate. We hypothesize that koalas will experience hyperthermia at high Ta but that behavioural strategies will reduce its incidence, and that Tb of koalas in poor health will have a more variable Tb than healthier individuals.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in summer 2019–2020 at the property ‘Dimberoy’ (31°07′33.2″S, 150°00′38.3″E), near the town of Gunnedah on the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. Dimberoy is a 2100-ha privately owned cattle farm with mature eucalypt woodland that provides habitat for the resident koala population (Crowther et al., 2022). Weather data during the study were obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology for the Gunnedah Airport weather station (BOM, 2020). Koala numbers in the region have declined with impacts of climate change as the area, characterized by humid, subtropical weather, has become drier (BOM, 2020). In 2009, an estimated 25% of the Gunnedah koala population perished during a drought and a series of heatwaves (Lunney et al., 2012). Since this time, chlamydiosis has become widespread in the region, including at the study site (Fernandez et al., 2019).

Data were collected under the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee approval number 2019/1547 and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Scientific License SL10233. Koalas were caught using the standard ‘flag and pole’ technique for capturing this species (Martin, 1989; Madani et al., 2020). An extendable pole was used to place a noose of soft rope around the neck of a koala to control its movement, while a flag on another extendable pole was waved above the koala’s head to encourage it to move down the tree. Once in reach of the catcher, koalas were manually restrained and placed in a capture bag. After capture, koalas were sedated with an intramuscular injection of alfaxalone (trade name Alfaxan®) at a dose rate of 1.8 mg kg−1 (Vogelnest and Portas, 2019). Then koalas were clinically evaluated, sexed, weighed and aged by tooth wear after Gordon (1991). Swabs were collected from the mucosal surface of the urogenital sinus and used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction to determine which individuals were positive/negative (binary variable) to C. pecorum (as in Fernandez et al., 2019). Delta cycle threshold (ΔCT) values, generated by subtracting CT values of koala beta-actin DNA from CT values of C. pecorum from the same swab sample (to account for differences in sample yield) and indicative of chlamydial shedding (Jackson et al., 1999), were utilized as proxy for disease severity (with higher ΔCT values representing lower chlamydial loads), as reduction in chlamydial shedding is associated with treatment (Markey et al., 2007).

Koalas were microchipped (Trovan ID100), given a uniquely numbered ear tag (Leader multitag 5430) and equipped with VHF tracking devices (ATS tag model M3420; mass, 30 g). Each koala was also given a small ingestible temperature logger (BodyCap Anipill, France), which travelled through the digestive system and lodged in the caecum (as evidenced by radiography during a pilot study of captive individuals; Mella et al., personal observation), allowing remote monitoring of Tbvia Bluetooth technology. The use of ingestible telemetric temperature loggers offers relatively non-invasive (as opposed to implants) measurements of Tb in medical and veterinary contexts (e.g. Angle and Gillette, 2011; Bongers et al., 2018). There is potential for intake of food and water to influence the temperature of an ingested logger, but the extensive hindgut and enormous caecum of koalas, combined with a long passage time (Lee and Carrick, 1989), would minimize any potential effect of feeding and drinking on loggers lodged in the caecum. Indeed, there was no change in Tb after drinking for the two koalas who drank from water stations during the study. Loggers were calibrated in the laboratory using a National Association of Testing Authorities-certified thermometer and a waterbath at temperatures from 15 to 51°C in 2°C increments. Loggers were programmed to record Tb at 5-min intervals for the duration of the study. When koalas had fully recovered from sedation, they were released at their point of capture.

A total of 12 koalas were captured for the study (eight males, four non-reproductive females), but the temperature loggers only recorded a single day (the last day) of Tb data for five koalas. These individuals were excluded from the statistical analyses, but their data provided information on koala Tb during the hottest day of the study period, which happened to coincide with the last day of the study.

Every day during the sampling period, each koala was radio tracked to make behavioural observations. Between one and three observations per koala (N = 7) were taken daily (n = 85 observations in total). All observations occurred between sunrise and sunset, and the koalas were tracked in a random order. The observer approached not closer than 10 m from the base of the tree in which they were located and photographed each koala using a digital camera (Canon EOS 1500D) to assess the degree of contact of their body with the tree (i.e. tree hugging, later scored on a scale from 1 = low contact to 3 = maximal contact; Fig. 1). Visits by individual koalas to supplemental water stations were recorded by microchip readers (Trovan® Dorset LID650 stationary decoders) and cameras (ScoutGuard model SG560K) as part of a different study (Mella et al., 2019). The data are used here to determine occurrence of drinking behaviour (binary variable: yes/no) during the study, assuming an acute effect of this behaviour on thermoregulation. However, as it rained daily during the data collection (max 2 mm day−1) and all koalas may have had access to rain water to drink (as in Mella et al., 2020), we also created a continuous variable to classify the koalas based on their frequency of access to the water stations (i.e. total number of visits per individual since water station were erected in 2017) and investigated whether regular access to free water (as opposed to short term) may influence thermoregulation. After 5–7 days, the koalas were recaptured and the temperature capsule data downloaded via Bluetooth to a handheld device.

Figure 1.

Examples of koala postures with varying levels of contact with the tree used to classify tree-hugging behaviour: (1) limited contact with the tree, (2) some contact with the tree and (3) full contact with the tree.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (Version 4.0.2; R Development Core Team, 2019) and StatistiXL (V2.0, www.statistiXL.com), and data are presented as mean ± SE, with N = number of individuals and n = number of measurements, unless stated otherwise. Time is presented as Australian eastern standard time. Body temperature measurements taken while koalas were captured and within 2 hrs of koalas being restrained or sedated were excluded from analyses, as these may have been affected by the response to capture, handling or anaesthesia (Adam et al., 2020).

We explored Tb in three ways: (i) Tb amplitude across the study period by evaluating the characteristics of a 24-hr cosinor function fitted to Tb data, to investigate overall differences between koalas owing to sex and disease, (ii) daily Tb by examining patterns of daily Tb oscillation in relation to daily ambient temperature conditions (i.e. the magnitude between daily Tb extreme values) and (iii) Tb at the time tree-hugging observations were made, to examine the direct effect of behaviour on Tb.

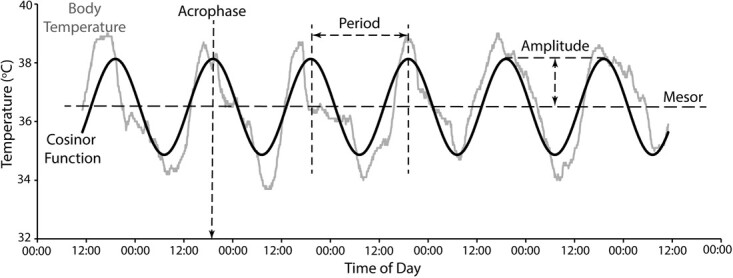

The diel Tb rhythm and degree of heterothermy exhibited by each individual koala (N = 7) for the entire duration of Tb measurement (4–7 days) was evaluated by fitting a 24-hr cosinor function to its daily pattern of Tb (Maloney et al., 2013; Maloney et al., 2017), using a custom-written Excel macro (S Maloney and P Withers, University of Western Australia; Fig. 2). Where the function’s fit was significant, the parameters of the rhythm including amplitude (presented as 2× the amplitude, i.e. max–min), 24-hr mesor (rhythm-adjusted mean), acrophase (time of the peak of the 24-hr cycle), period (duration of a single cycle) and goodness of fit of the daily rhythm (R2) were calculated after Nelson et al. (1979). We used a linear model using the ‘lm’ function (R Development Core Team, 2019) to determine if the factors sex and disease (presence/absence and severity in separate analysis) influenced the amplitude of Tb and the goodness of fit of the 24-hr cosinor function. Mass was excluded from the model as sex and mass were confounded (i.e. males were heavier than females). Frequency distributions of male and female koala Tb were determined separately and analysed for skewness and kurtosis using StatistiXL.

Figure 2.

Cosinor function (dark line) and koala body temperature (grey line) showing the diel Tb rhythm and degree of heterothermy exhibited by an individual koala for the duration of the study. The various rhythm characteristics (acrophase; period; mesor; amplitude, analysed as 2× the amplitude) of the cosinor analysis are indicated by dashed lines.

The absolute daily (n = 4–7 days) amplitude of Tb (N = 7, n = 41) and Ta were quantified as the difference between the absolute daily maximum and minimum temperatures (calculated from 0000 to 2359 hrs). Three separate linear mixed effect models (LMM), using the ‘lme4’ package (Bates et al., 2015), were then used to determine the relationship between (i) absolute daily Tb amplitude, (ii) absolute daily maximum Tb and (iii) absolute daily minimum Tb (response variables) and the fixed factors daily Ta amplitude, drinking behaviour (yes/no and frequency in separate analysis) and disease (presence/absence and severity in separate analysis), with koala identity (ID) and day as random factors to account for repeated measurements of individuals. Finally, we used an LMM to explore the effects of Ta, tree hugging and disease (both presence/absence and severity) on koala Tb at the time of observation (N = 7, n = 84), with koala ID nested in day as a random factor.

Results

Body mass of the koalas ranged from 5.6 to 9.3 kg (N = 12) and estimated age from 3 to ≥9 years. For the koalas included in the statistical analysis (N = 7), body mass ranged from 6.1 to 9.1 kg and estimated age was ≥9 years. Two individuals (one male and one female) were negative for C. pecorum, while the other five koalas were positive, with CT values ranging from 22.3 to 31.3. Only two male koalas accessed the water stations during the study, but five individuals (three males and two females) were habitual visitors to the water stations, with an average of one visit every 3 days in the preceding 3 years (since the water stations were erected), while two koalas (one male and one female) never used the stations.

Mean daily minimum Ta during the study was 23.3°C (range, 21.3–26.7°C) and mean daily maximum Ta was 38.3°C (range, 35.4–40.9°C; BOM, 2020). Total rainfall for this period was 15 mm (Dimberoy property rain gauge). Mean koala Tb during the study was 36.4°C (N = 7; n = 1656), mean minimum Tb was 34.4°C (range, 32.8–35.9°C) and mean maximum Tb was 38.6°C (range, 37.6–39.4°C). Mean daily range in koala Tb recorded in this study was 4.1°C (range, 2.3–6°C).

The absolute minimum and maximum koala Tb recorded during the study occurred on 30 January 2020. Mean Ta on this day was 31.7°C, with the daily minimum of 23.3°C occurring between 0610 and 0630 hrs and the daily maximum of 40.8°C occurring at 1610 hrs. On the same day, the highest koala Tb recorded (40.8°C) occurred between 1621 and 1814 hrs, but also the lowest Tb recorded (32.4°C) occurred on this day between 0747 and 0754 hrs.

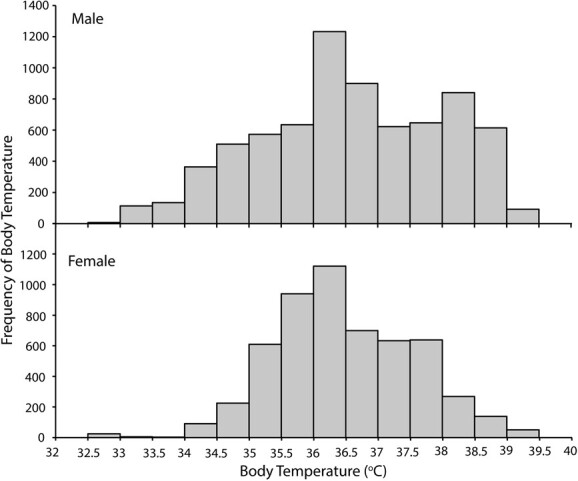

The cosinor function was highly significant for all individuals (F2,1433–2014, P < 0.001), with R2 ranging from 0.62 to 0.84. The acrophase occurred between mid-afternoon and evening (1604–2010 hrs) with an amplitude of 1.5 to 3.3°C and a mesor of 36.3 ± 0.01 to 36.6 ± 0.02°C. The amplitude of Tb and goodness of fit of the daily rhythm were significantly affected by sex (F1,4 = 13.2, P = 0.022 and F1,4 = 16.7, P = 0.01,4 respectively; Fig. 3), with males having a greater Tb amplitude and more pronounced 24-hr rhythm than females. Disease severity did not influence Tb amplitude or goodness of fit of the daily rhythm (F1,4 = 1.8, P = 0.254, and F1,4 = 7.1, P = 0.056, respectively), but healthy koalas in general did have a better goodness of fit of the daily rhythm to a 24-hr period than diseased koalas (F1,4 = 9.1, P = 0.039; Fig. 4). The Tb distribution of male koalas was negatively skewed (skewness = −0.201, P < 0.001) and kurtotic (kurtosis = −0.705, P < 0.001), while that of female koalas was positively skewed (skewness = 0.075, P = 0.023) but was not kurtotic (kurtosis = −0.013, P = 0.822; Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

2× the amplitude (black) and goodness of fit (R2; white) of a cosinor analysis of body temperature (°C) for free-living koalas (P. cinereus) on the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. There is a significant difference between males and females for both variables. Values are mean ± SE, N = 7.

Figure 4.

The effect of chlamydial disease status (positive/negative) on the daily rhythm goodness of fit (R2) of wild koalas in the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. There is a significant difference between C. pecorum positive and negative koalas. Values are mean ± SE, N = 7.

Figure 5.

Body temperature distribution of wild male and female koalas (P. cinereus; N = 7) in the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. Male body temperature frequency was negatively skewed and kurtotic; female body temperature frequency was positively skewed.

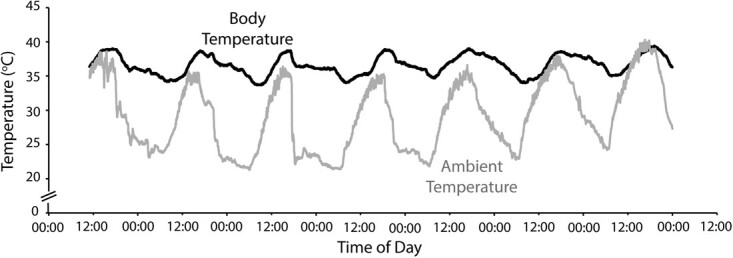

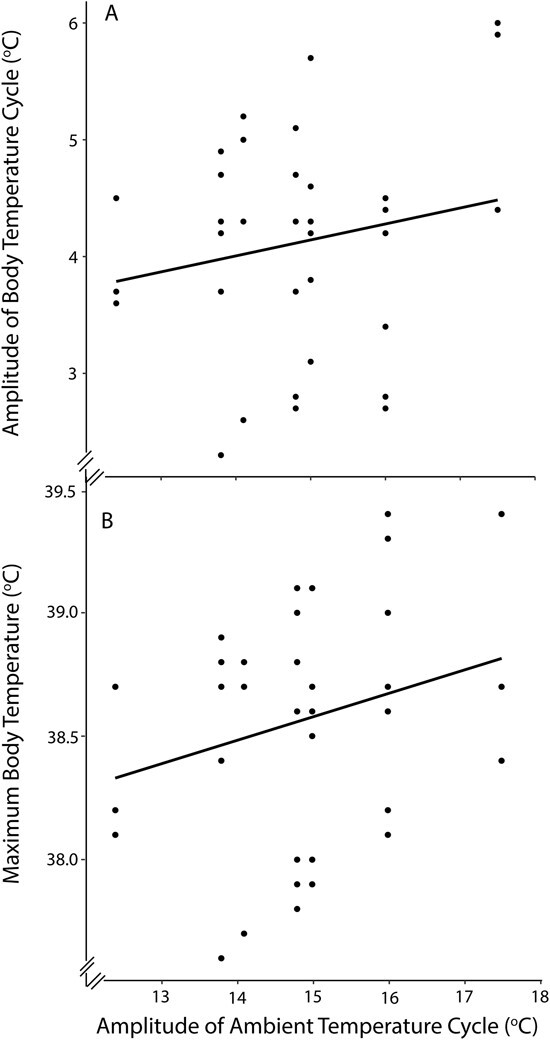

Daily Tb amplitude and daily maximum Tb were significantly affected by daily Ta amplitude (F1,7 ≥ 6.7, P ≤ 0.037, and F1,10 ≥ 17.7, P ≤ 0.044, respectively; Figs 6 and 7) but not by drinking behaviour (F1,4 ≤ 2.6, P ≥ 0.181, and F1,4 ≤ 2.0, P ≥ 0.232, respectively) or disease (F2,7 ≤ 1.2, P ≥ 0.349, and F2,6 ≤ 1.8, P ≥ 0.265, respectively). Daily minimum Tb was not affected by daily Ta amplitude (F1,7 ≤ 1.3, P ≥ 0.288), drinking behaviour (F1,4 ≤ 2.7, P ≥ 0.174) or disease (F1,4 ≤ 2.6, P ≥ 0.183). There was no correlation between daily minimum Tb and daily maximum Ta (r = −0.03; P = 0.841).

Figure 6.

Body temperature (°C; black line) of a wild koala (P. cinereus) in the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia, plotted alongside ambient temperature (°C; grey line) at the study site for the same period.

Figure 7.

The effect of the daily ambient temperature cycle amplitude (°C) on (A) daily body temperature amplitude (°C) and (B) maximum daily body temperature (°C) of wild koalas (N = 7, n = 41) in the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. The solid line is the relationship for the linear mixed model relating koala body temperature to ambient temperature amplitude, including drinking behaviour and disease as additional fixed factors with koala identity and day as random factors.

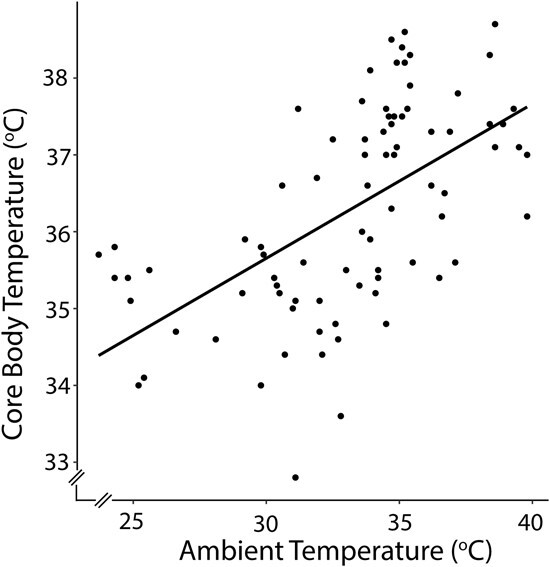

Koalas were observed mainly in Eucalyptus populnea (n = 69) and less often in Eucalyptus albens (n = 9) and Eucalyptus melliodora (n = 6) trees. All koalas were observed engaging in varied tree-hugging behaviour (scores 1–3), which weakly correlated with Ta (r = 0.3, P = 0.011). Koala Tb at the time behavioural observations were made was significantly affected by Ta (F1,75 ≥ 63.7, P < 0.001), increasing as Ta increased (Fig. 8), while neither tree hugging (F1,68 ≤ 1.18, P ≥ 0.281) nor disease (F1,72 ≤ 1.41, P ≥ 0.239) influenced koala Tb.

Figure 8.

The effect of ambient temperature (°C) on wild koala body temperature (°C) at the time of behavioural observation (N = 7, n = 84) in the Liverpool Plains, NSW, Australia. The solid line is the relationship for the linear mixed model relating koala body temperature to ambient temperature, including tree-hugging behaviour and disease as additional fixed factors with koala identity and day as random factors.

Discussion

We investigated if weather, behaviour and chlamydial disease influenced thermoregulation of free-ranging koalas. Ta had highly significant effects on koala Tb that could not be compensated for with thermoregulatory behavioural strategies (i.e. tree hugging and drinking). Disease impacted the 24-hr Tb rhythm, but there was no evidence that severity of infection impacted Tb.

We recorded both the lowest (Tb = 32.4°C) and the highest (Tb = 40.8°C) Tb ever documented for free-ranging koalas. While the mean Tb (36.4 ± 0.05°C) was consistent with previous studies (Robinson, 1954; Dickens, 1975; Degabriele and Dawson, 1979; Adam et al., 2016; Adam et al., 2020), the minimum and maximum Tb in our study were 1.8°C above and below the most extreme Tb previously recorded for wild koalas, and maximum Tb was 0.8°C above even the highest recorded Tb for restrained individuals (Adam et al., 2020). All koalas used in this study were still alive at least 6 months after data collection (i.e. recaptured as part of a study by Simpson et al., 2023). This is evidence that koalas can survive more extreme Tb than was previously thought, and that they employ heterothermia during conditions of heat and aridity.

Hyperthermia at high Ta reduces the gradient for environmental heat gain and the water expended on evaporative heat loss but is accompanied by an increased heat production due to the Q10 effect on metabolic rate, and a risk of death if Tb exceeds the species upper critical limit (Hetem et al., 2014; Gerson et al., 2019; Turner, 2020). We calculated that allowing Tb to increase from 36.4 to 40.8°C results in substantial water saving of ~ 54 ml or 18% of the daily water turnover (~300 ml day−1; Mella et al., unpublished data) of a koala at this site (assuming the specific heat of tissues is 3.9 J g−1°C−1 and latent heat of evaporation is 2.4 kJ g−1; Withers, 1992). However, a Tb of 40.8°C is approaching that assumed to be fatal for other folivorous marsupials (Cooper et al., 2020), as an increase of 4–6°C beyond normothermia (i.e. Tb of 40.4–42.4°C for koalas) is typically lethal for mammals (Cossins and Bowler, 1987; McKechnie and Wolf, 2019). Interestingly, however, koalas with regular access to supplementary water (which included the individual with the highest Tb recorded in the study) did not thermoregulate more tightly than other individuals, as instead observed in other species (Czenze et al., 2020). Therefore, it appears that either access to drinking water does not lead to more effective thermoregulation for koalas at high Ta or that it was the individuals most thermally challenged that exploited the available drinking water to maintain Tb below lethal limits. However, we consider this unlikely as the two individual koalas that visited the water stations at the study site during data collection had a stable Tb of 36°C recorded before and after drinking water, supporting the hypothesis that drinking did not translate into more efficient thermoregulation.

The highest Tb recorded for all of the koalas occurred during the late afternoon and evening of 1 day of extremely high maximum Ta, but these high Tb were typically preceded by the lowest recorded Tb. Lower Tb in the mornings of hotter days were also observed for western grey kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus; Maloney et al., 2004). The authors concluded that changes in circannual rhythm or food availability drove these long-term patterns in Tb for kangaroos. However, our similar observations for koalas suggest that pre-emptively lowering morning Tb on extremely hot days may provide greater scope for heat storage throughout the day, reducing requirements for evaporative cooling during the hottest parts of the day. This strategy requires individuals to predict days of extreme Ta from night and morning conditions and adjust Tb regulation accordingly. Zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) modify their feeding and drinking behaviour in the early mornings of days of high maximum Ta (Cooper et al., 2019), so such predictions by wild animals are possible. Our results show, for the first time, that koalas appear to predict environmental conditions to better deal with extreme heat.

The cosinor analysis indicated a significant 24-hr Tb rhythm, with the timing of the acrophase consistent with peak Tb reported by Adam et al. (2020) and correlating with increased activity in the evening (Logan and Sanson, 2002; Ryan et al., 2013). It is typical for the Tb acrophase of mammals to correlate with the timing of maximal activity (e.g. Refinetti and Menaker, 1992; Hetem et al., 2019). We observed a higher Tb amplitude, more pronounced Tb rhythm and kurtosis of Tb distribution for males, presumably a consequence of their longer movements, and more frequent tree changes (Ryan et al., 2013) as activity impacts the shape and amplitude of the diel body temperature cycle (Refinetti, 2010). The negative skew of their Tb distribution further suggests that larger, more active males may face greater energetic challenges than females.

Diseased koalas had disrupted 24-hr Tb rhythms. The amplitude of Tb rhythm is widely appreciated to be an indicator of health and fitness for mammals (e.g. Kamerman et al., 2001; Maloney et al., 2017; Maloney et al., 2019), but illness, injury and disease can also disrupt the 24-hr Tb cycle due to the close interrelationship between the immune system, circadian rhythm and Tb, although this is more widely appreciated for humans than other mammals (Refinetti and Menaker, 1992; Culver et al., 2020; Coiffard et al., 2021). We demonstrate that disease disrupts the rhythmicity of Tb for koalas. The most likely mechanism by which chlamydiosis may impact Tb is through the urinary incontinence seen in affected koalas (Griffith, 2010), compromising water balance and reducing the water available for evaporative cooling in diseased animals, irrespective of their infection load.

Energetic and nutritional challenges impact on the ability of mammals to maintain thermoregulatory homeostasis (Hetem et al., 2019). Herbivores voluntarily reduce their food intake as a response to increased Ta (Beale et al., 2018), but chronic reduction in feed intake, coupled with the associated dehydration, may have severe impacts on the health and survival of koalas in a hot, dry climate (Lepock, 1997; Beale et al., 2018; Youngentob et al., 2021). The high amplitude of the cosinor function (1.5–3.3°C) compared to that of long-term Tb amplitude for comparable previous studies (e.g. 1.2°C; Adam et al., 2020) results not only from a higher maximum Tb, but also a lower minimum Tb, suggesting that these koalas are energy limited (Hetem et al., 2016), likely due to ageing. All the koalas included in the analyses were old adults (<9 years). Energy and nutritional uptake for herbivores depends on mastication efficiency (Pérez-Barbería and Gordon, 1998), and the ability of koalas to process food reduces with age as tooth wear increases (Logan, 2003). Similarly, sheep reduced minimum Tb and increased the amplitude of their diel cycle when energy intake was less than required for maintenance (Maloney et al., 2013), and the diel Tb amplitude of aardvarks (Orycteropus afer) increased with starvation during a summer drought (Rey et al., 2017).

Trees provide a microhabitat fundamental for koala survival. They offer a barrier against solar radiation (Crowther et al., 2014), feed (Clifton et al., 2007), water (Mella et al., 2020) and in some cases a cool surface for heat dissipation (Kavanagh et al., 2007; Briscoe et al., 2014). We expected tree hugging to lower Tb, as the thin fur across the koala ventral and inner thigh regions allows for heat exchange with the tree (Briscoe et al., 2014; Briscoe et al., 2015). However, we found that the degree of contact between the koala and tree did not affect Tb, and high level of tree hugging in hot conditions was not a predominant strategy, possibly because of the characteristics of the trees available to this population. Koalas were predominantly observed in rough bark trees (i.e. E. populnea) likely limiting the close approximation between the koalas and trees necessary to facilitate heat exchange.

Our results indicate that Ta is a major determinant of koala Tb, affecting daily Tb amplitude, daily maximum Tb and absolute Tb. We have demonstrated that koalas can tolerate short periods of high Ta and associated hyperthermia. However, considering their Tb approaches potentially lethal levels (Lepock, 1997) at high Ta and their unfavourable relative water economy (Cooper et al., 2020), prolonged heat stress for koalas is potentially fatal (Adams-Hosking et al., 2011). Consequently, the increase in Ta, combined with more frequent and severe heatwaves throughout the koala habitat expected with current climate predictions, seriously threatens koala survival (Hughes, 2003; Kirono et al., 2011). Suitable trees that provide koalas with the microhabitat required for thermoregulation during severe weather events are becoming rarer (Kirono et al., 2011; Adams-Hosking et al., 2012), and favoured trees in the Liverpool Plains region did not afford effective conductive heat exchange.

Our study highlights the importance of climate change projections for koala conservation and suggests that future species management should consider the thermoregulatory limits of koalas and their interaction with chlamydial disease. Our conclusions also apply to other specialist herbivores, which are likely impacted by climate change, and hence our results are globally relevant. Mammalian herbivores are a highly interactive component of most ecosystems on most continents, shaping plant–herbivore–predator dynamics, so their conservation has significant ecological consequences.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rob Frend and family for allowing access to their property, A/Prof. Damien Higgins, Cristina Fernandez and Alexis Priola for assistance with data collection in the field, Laura Woolfenden for her assistance in the laboratory, Prof. Philip Withers and Prof. Shane Maloney for providing us with their cosinor Excel macro and Prof. Mathew Crowther and Dr Evelyn Hall for statistical analysis advice.

Author Contributions

Valentina S.A. Mella: conceptualization, experimental design, data collection, data analysis, project administration, writing and editing. Christine E. Cooper: data curation, data analysis, writing and editing. Madeline Karr: data collection and writing. Andrew Krockenberger: conceptualization, experimental design and editing. George Madani: data collection, writing and editing. Elliot B. Webb: data analysis and editing. Mark B. Krockenberger: conceptualization, experimental design and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The project was funded by the University of Sydney NSW Industry and Community Seed Fund, in collaboration with the NSW North West Local Landcare Service, and by philanthropic donations to the 2018 University of Sydney Pave the Way Campaign for the project Koalas and Climate Change.

Data Availability

The data used to generate the results in the paper are available on the Sydney eScholarship Repository under the following identifier: https://url.au.m.mimecastprotect.com/s/8xu6Cq71mwfL7Zqj2iZK5iP?domain=hdl.handle.net.

Contributor Information

Valentina S A Mella, Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia; School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia.

Christine E Cooper, School of Molecular and Life Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia 6102, Australia.

Madeline Karr, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia.

Andrew Krockenberger, Division of Research and Innovation, James Cook University, Cairns, Queensland 4878, Australia.

George Madani, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia.

Elliot B Webb, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia; Department of Planning and Environment, Science, Economics and Insights Division, Parramatta, New South Wales 2150, Australia.

Mark B Krockenberger, Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia.

References

- Adam D, Johnston S, Beard L, Nicholson V, Lisle A, Gaughan J, Larkin R, Theilemann P, Mckinnon A, Ellis W (2016) Surgical implantation of temperature-sensitive transmitters and data-loggers to record body temperature in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust Vet J 94: 42–47. 10.1111/avj.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam D, Johnston SD, Beard L, Nicolson V, Gaughan JB, Lisle AT, FitzGibbon S, Barth BJ, Gillett A, Grigg Get al. (2020) Body temperature of free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) in south-east Queensland. Int J Biometeorol 64: 1305–1318. 10.1007/s00484-020-01907-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Hosking C, Grantham HS, Rhodes JR, McAlpine C, Moss PT (2011) Modelling climate-change-induced shifts in the distribution of the koala. Wildl Res 38: 122. 10.1071/WR10156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Hosking C, McAlpine C, Rhodes JR, Grantham HS, Moss PT (2012) Modelling changes in the distribution of the critical food resources of a specialist folivore in response to climate change. Divers Distrib 18: 847–860. 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2012.00881.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angle TC, Gillette RL (2011) Telemetric measurement of body core temperature in exercising unconditioned Labrador retrievers. Can J Vet Res 75: 157–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67: 1. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beale PK, Marsh KJ, Foley WJ, Moore BD (2018) A hot lunch for herbivores: physiological effects of elevated temperatures on mammalian feeding ecology. Biol Rev 93: 674–692. 10.1111/brv.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOM (2020) Bureau of Metereology. In Latest Weather Observations for Gunnedah Airport. Accessed in January 2020 athttp://www.bom.gov.au/products/IDN60801/IDN60801.95740.shtml

- Bongers CCWG, Hopman MTE, Eijsvogels TMH (2018) Validity and reliability of the myTemp ingestible temperature capsule. J Sci Med Sport 21: 322–326. 10.1016/j.jsams.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozinovic F, Bastías DA, Boher F, Clavijo-Baquet S, Estay SA, Angilletta MJ Jr (2011) The mean and variance of environmental temperature interact to determine physiological tolerance and fitness. Physiol Biochem Zool 84: 543–552. 10.1086/662551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe NJ, Handasyde KA, Griffiths SR, Porter WP, Krockenberger A, Kearney MR (2014) Tree-hugging koalas demonstrate a novel thermoregulatory mechanism for arboreal mammals. Biol Lett 10: 20140235. 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe NJ, Krockenberger A, Handasyde KA, Kearney MR (2015) Bergmann meets Scholander: geographical variation in body size and insulation in the koala is related to climate. J Biogeogr 42: 791–802. 10.1111/jbi.12445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Grice RG (1984) Isolation of Chlamydia psittaci from koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust Vet J 61: 413. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1984.tb07182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield P, Spencer A (1993) Renal complications of cystitis in koalas. Aust Vet J 70: 310–311. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1993.tb07983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle C, Brown A, Filippich L, Reynolds K, Reynolds W (1989) Intravenous urography in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Vet Radiol 30: 34–40. 10.1111/j.1740-8261.1989.tb00750.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charalambous R, Narayan E (2020) A 29-year retrospective analysis of koala rescues in New South Wales, Australia. PLoS 1 15: e0239182. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton ID (2010) High koala mortality associated with low browse moisture in tropical environments. Aust Mammal 32: 157. 10.1071/AM10015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton ID, Ellis WA, Melzer A, Tucker G (2007) Water turnover and the northern range of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust Mammal 29: 85. 10.1071/AM07010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coiffard B, Diallo AB, Mezouar S, Leone M, Mege JL (2021) A tangled threesome: circadian rhythm, body temperature variations, and the immune system. Biology (Basel) 10: 65–80. 10.3390/biology10010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Withers PC, Hurley LL, Griffith SC (2019) The field metabolic rate, water turnover, and feeding and drinking behavior of a small avian desert granivore during a summer heatwave. Front Physiol 10. 10.3389/fphys.2019.01405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Withers PC, Turner JM (2021) Physiological implications of climate change for a critically endangered Australian marsupial. Aust J Zool 68: 200–211. 10.1071/ZO20067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cossins AR, Bowler K (1987) Temperature Biology of Animals. Springer, Dordrecht [Google Scholar]

- Crowther MS, Lunney D, Lemon J, Stalenberg E, Wheeler R, Madani G, Ross KA, Ellis M (2014) Climate-mediated habitat selection in an arboreal folivore. Ecography 37: 336–343. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther MS, Rus AI, Mella VSA, Krockenberger MB, Lindsay J, Moore BD, McArthur C (2022) Patch quality and habitat fragmentation shape the foraging patterns of a specialist folivore. Behav Ecol 33: 1007–1017. 10.1093/beheco/arac068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver A, Coiffard B, Antonini F, Duclos G, Hammad E, Vigne C, Mege JL, Baumstarck K, Boucekine M, Zieleskiewicz Let al. (2020) Circadian disruption of core body temperature in trauma patients: a single-center retrospective observational study. J Intensive Care 8: 4. 10.1186/s40560-019-0425-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czenze ZJ, Kemp R, Jaarsveld B, Freeman MT, Smit B, Wolf BO, McKechnie AE (2020) Regularly drinking desert birds have greater evaporative cooling capacity and higher heat tolerance limits than non-drinking species. Funct Ecol 34: 1589–1600. 10.1111/1365-2435.13573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TJ, Hulbert A (1970) Standard metabolism, body temperature, and surface areas of Australian marsupials. Am J Physiol Legacy Content 218: 1233–1238. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.4.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degabriele R (1980) The physiology of the koala. Sci Am 243: 110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degabriele R, Dawson TJ (1979) Metabolism and heat balance in an arboreal marsupial, the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). J Comp Physiol 134: 293–301. 10.1007/BF00709996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens R (1975) The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) past, present and future. Aust Vet J 51: 459–463. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis W, Melzer A, Clifton I, Carrick F (2010) Climate change and the koala Phascolarctos cinereus: water and energy. Aust Zool 35: 369–377. 10.7882/AZ.2010.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPBCA (1999) Environment protection and biodiversity conservation act. Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed in January 2020 athttps://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A00485. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez CM, Krockenberger MB, Valentina M, Mella SA, Wright BR, Crowther MS, Higgins DP (2024) A novel multi-variate immunological approach, reveals immune variation associated with environmental conditions, and co-infection in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Sci Rep 14: 7260. 10.1038/s41598-024-57792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez CM, Schmertmann LJ, Higgins DP, Casteriano A, Irinyi L, Mella VS, Crowther MS, Meyer W, Krockenberger MB (2019) Genetic differences in Chlamydia pecorum between neighbouring sub-populations of koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Vet Microbiol 231: 264–270. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B, Scholer M, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Fitzpatrick J (2018) Climate change causes upslope shifts and mountaintop extirpations in a tropical bird community. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115: 11982–11987. 10.1073/pnas.1804224115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuente A, Williams SE (2023) Climate change threatens the future of rain forest ringtail possums by 2050. Divers Distrib 29: 173–183. 10.1111/ddi.13652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller A, Dawson T, Helmuth B, Hetem RS, Mitchell D, Maloney SK (2010) Physiological mechanisms in coping with climate change. Physiol Biochem Zool 83: 713–720. 10.1086/652242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson AR, McKechnie AE, Smit B, Whitfield MC, Smith EK, Talbot WA, McWhorter TJ, Wolf BO (2019) The functional significance of facultative hyperthermia varies with body size and phylogeny in birds. Funct Ecol 33: 597–607. 10.1111/1365-2435.13274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G (1991) Estimation of the age of the koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Marsupialia: Phascolarctidae) from tooth wear and growth. Aust Mammal 14: 5. 10.1071/AM91001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G, Brown A, Pulsford T (1988) A koala (Phascolarctos cinereus Goldfuss) population crash during drought and heatwave conditions in south-western Queensland. Aust J Ecol 13: 451–461. 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1988.tb00993.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JE (2010) Studies into the Diagnosis, Treatment and Management of Chlamydiosis in Koalas . PhD Thesis. The University of Sydney, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Harvell CD, Mitchell CE, Ward JR, Altizer S, Dobson AP, Ostfeld RS, Samuel MD (2002) Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296: 2158–2162. 10.1126/science.1063699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley DM, DuRant SE, Wilson AF, Adelman JS, Hopkins WA (2012) Additive metabolic costs of thermoregulation and pathogen infection. Funct Ecol 26: 701–710. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.01978.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hetem RS, Fuller A, Maloney SK, Mitchell D (2014) Responses of large mammals to climate change. Temperature (Austin) 1: 115–127. 10.4161/temp.29651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetem RS, Maloney SK, Fuller A, Mitchell D (2016) Heterothermy in large mammals: inevitable or implemented? Biol Rev 91: 187–205. 10.1111/brv.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetem RS, Mitchell D, BA DEW, Fick LG, Maloney SK, Meyer LCR, Fuller A (2019) Body temperature, activity patterns and hunting in free-living cheetah: biologging reveals new insights. Integr Zool 14: 30–47. 10.1111/1749-4877.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes L (2003) Climate change and Australia: trends, projections and impacts. Austral Ecol 28: 423–443. 10.1046/j.1442-9993.2003.01300.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, White N, Giffard P, Timms P (1999) Epizootiology of Chlamydia infections in two free-range koala populations. Vet Microbiol 65: 255–264. 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerman PR, Fuller A, Faurie AS, Mitchell G, Mitchell D (2001) Body temperature patterns during natural fevers in a herd of free-ranging impala (Aepyceros melampus). Vet Rec 149: 26–27. 10.1136/vr.149.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh RP, Stanton MA, Brassil TE (2007) Koalas continue to occupy their previous home-ranges after selective logging in Callitris–Eucalyptus forest. Wildl Res 34: 94. 10.1071/WR06126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirono D, Kent D, Hennessy K, Mpelasoka F (2011) Characteristics of Australian droughts under enhanced greenhouse conditions: results from 14 global climate models. J Arid Environ 75: 566–575. 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kollipara A, George C, Hanger J, Loader J, Polkinghorne A, Beagley K, Timms P (2012) Vaccination of healthy and diseased koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) with a Chlamydia pecorum multi-subunit vaccine: evaluation of immunity and pathology. Vaccine 30: 1875–1885. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krockenberger AK, Edwards W, Kanowski J (2012) The limit to the distribution of a rainforest marsupial folivore is consistent with the thermal intolerance hypothesis. Oecologia 168: 889–899. 10.1007/s00442-011-2146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AK, Carrick FN (1989) Phascolarctidae. In Walton DW, Richardson J, eds, Fauna of Australia Vol 1B Mammalia 740–754. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra [Google Scholar]

- Lepock JR (1997) Protein denaturation during heat shock. In Bittar EE, Willis JS, eds, Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology. Elsevier, pp. 223–259 [Google Scholar]

- Logan M (2003) Effect of tooth wear on the rumination-like behavior, or merycism, of free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). J Mammal 84: 897–902. 10.1644/BBa-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan M, Sanson GD (2002) The effect of tooth wear on the feeding behaviour of free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus, Goldfuss). J Zool 256: 63–69. 10.1017/S0952836902000080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lunney D, Crowther MS, Wallis I, Foley WJ, Lemon J, Wheeler R, Madani G, Orscheg C, Griffith JE, Krockenberger M (2012) Koalas and climate change: a case study on the Liverpool Plains, north-west New South Wales. In Lunney D, Hutchings P, eds, Wildlife and Climate Change: Towards Robust Conservation Strategies for Australian Fauna Vol 150

- Madani G, Ashman K, Mella V, Whisson D (2020) A review of the ‘noose and flag’ method to capture free-ranging koalas. Aust Mammal 42: 341. 10.1071/AM19064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney S, Fuller A, Kamerman P, Mitchell G, Mitchell D (2004) Variation in body temperature in free-ranging western grey kangaroos Macropus fuliginosus. Aust Mammal 26: 135. 10.1071/AM04135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney S, Goh G, Fuller A, Vesterdorf K, Blache D (2019) Amplitude of the circadian rhythm of temperature in homeotherms. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, 14: 1–30 [Google Scholar]

- Maloney SK, Marsh MK, McLeod SR, Fuller A (2017) Heterothermy is associated with reduced fitness in wild rabbits. Biol Lett 13: 20170521. 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney SK, Meyer LC, Blache D, Fuller A (2013) Energy intake and the circadian rhythm of core body temperature in sheep. Physiol Rep 1: e00118. 10.1002/phy2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey B, Wan C, Hanger J, Phillips C, Timms P (2007) Use of quantitative real-time PCR to monitor the shedding and treatment of chlamydiae in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Vet Microbiol 120: 334–342. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R (1989) Draft management plan for the conservation of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) in Victoria. In Technical Report Series No. 99. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Conservation, Forests & Lands, Victoria, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Martin RW, Handasyde KA, Krockenberger A (2008) Koala. In Dyck S, Strahan R, eds, The Mammals of Australia: 198–201. Reed New Holland, Sydney [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie AE, Wolf BO (2010) Climate change increases the likelihood of catastrophic avian mortality events during extreme heat waves. Biol Lett 6: 253–256. 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie AE, Wolf BO (2019) The physiology of heat tolerance in small endotherms. Phys Ther 34: 302–313. 10.1152/physiol.00011.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mella VSA, McArthur C, Krockenberger MB, Frend R, Crowther MS (2019) Needing a drink: rainfall and temperature drive the use of free water by a threatened arboreal folivore. PLoS One 14: e0216964. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mella VSA, Orr C, Hall L, Velasco S, Madani G (2020) An insight into natural koala drinking behaviour. Ethology 126: 858–863. 10.1111/eth.13032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy K, Martin R (1985) Field metabolic rate, water flux, food consumption and time budget of koalas, Phascolarctos cinereus (Marsupialia: Phascolarctidae) in Victoria. Aust J Zool 33: 655. 10.1071/ZO9850655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan EJ, Williams M (2016) Understanding the dynamics of physiological impacts of environmental stressors on Australian marsupials, focus on the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). BMC Zool 1: 2. 10.1186/s40850-016-0004-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W, Tong YL, Lee JK, Halberg F (1979) Methods for cosinor-rhythmometry. Chronobiologia 6: 305–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Barbería FJ, Gordon IJ (1998) Factors affecting food comminution during chewing in ruminants: a review. Biol J Linn Soc 63: 233–256. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1998.tb01516.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S, Wallis K, Lane A (2021) Quantifying the impacts of bushfire on populations of wild koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus): insights from the 2019/20 fire season. Ecol Manage Restor 22: 80–88. 10.1111/emr.12458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne A, Hanger J, Timms P (2013) Recent advances in understanding the biology, epidemiology and control of chlamydial infections in koalas. Vet Microbiol 165: 214–223. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.6.1. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [Google Scholar]

- Reckless HJ, Murray M, Crowther MS (2017) A review of climatic change as a determinant of the viability of koala populations. Wildl Res 44: 458. 10.1071/WR16163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Refinetti R (2010) The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 15: 564. 10.2741/3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refinetti R, Menaker M (1992) The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Physiol Behav 51: 613–637. 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey B, Fuller A, Mitchell D, Meyer LCR, Hetem RS (2017) Drought-induced starvation of aardvarks in the Kalahari: an indirect effect of climate change. Biol Lett 13: 20170301. 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KW (1954) Heat tolerances of Australian monotremes and marsupials. Aust J Biol Sci 7: 348–360. 10.1071/BI9540348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MA, Whisson DA, Holland GJ, Arnould JPY (2013) Activity patterns of free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) revealed by accelerometry. PLoS One 8: e80366. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid LM, Schmid KL, Brown B (1991) Behavioural determination of visual function in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Wildl Res 18: 367. 10.1071/WR9910367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SJ, Higgins DP, Timms P, Mella VSA, Crowther MS, Fernandez CM, McArthur C, Phillips S, Krockenberger MB (2023) Efficacy of a synthetic peptide Chlamydia pecorum major outer membrane protein vaccine in a wild koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) population. Sci Rep 13: 15087. 10.1038/s41598-023-42296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JM (2020) Facultative hyperthermia during a heatwave delays injurious dehydration of an arboreal marsupial. J Exp Biol 223: jeb.219378. 10.1242/jeb.219378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelnest L, Portas T (2019) Current Therapy in Medicine of Australian Mammals. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton South, Victoria, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Welbergen JA, Klose SM, Markus N, Eby P (2008) Climate change and the effects of temperature extremes on Australian flying-foxes. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 275: 419–425. 10.1098/rspb.2007.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Bolitho E, Fox S (2003) Climate change in Australian tropical rainforests: an impending environmental catastrophe. Proc R Soc B 270: 1887–1892. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers PC (1992) Comparative Animal Physiology. Saunders College Publishing, Fort Worth, USA [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob KN, Lindenmayer DB, Marsh KJ, Krockenberger AK, Foley WJ (2021) Food intake: an overlooked driver of climate change casualties? Trends Ecol Evol 36: 676–678. 10.1016/j.tree.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]