Abstract

Background

Since the mid‐1970s, short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapies (STPP) for a broad range of psychological and somatic disorders have been developed and studied. Early published meta‐analyses of STPP, using different methods and samples, have yielded conflicting results, although some meta‐analyses have consistently supported an empirical basis for STPP. This is an update of a review that was last updated in 2006.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of STPP for adults with common mental disorders compared with wait‐list controls, treatments as usual and minimal contact controls in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). To specify the differential effects of STPP for people with different disorders (e.g. depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, mixed disorders and personality disorder) and treatment characteristics (e.g. manualised versus non‐manualised therapies).

Search methods

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR) was searched to February 2014, this register includes relevant randomised controlled trials from The Cochrane Library (all years), EMBASE (1974‐), MEDLINE (1950‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐). We also conducted searches on CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, DARE and Biological Abstracts (all years to July 2012) and all relevant studies (identified to 2012) were fully incorporated in this review update. We checked references from papers retrieved. We contacted a large group of psychodynamic researchers in an attempt to find new studies.

Selection criteria

We included all RCTs of adults with common mental disorders, in which a brief psychodynamic therapy lasting 40 or fewer hours in total was provided in individual format.

Data collection and analysis

Eight review authors working in pairs evaluated studies. We selected studies only if pairs of review authors agreed that the studies met inclusion criteria. We consulted a third review author if two review authors could not reach consensus. Two review authors collected data and entered it into Review Manager software. Two review authors assessed and scored risk of bias. We assessed publication bias using a funnel plot. Two review authors conducted and reviewed subgroup analyses.

Main results

We included 33 studies of STPP involving 2173 randomised participants with common mental disorders. Studies were of diverse conditions in which problems with emotional regulation were purported to play a causative role albeit through a range of symptom presentations. These studies evaluated STPP for this review's primary outcomes (general, somatic, anxiety and depressive symptom reduction), as well as interpersonal problems and social adjustment. Except for somatic measures in the short‐term, all outcome categories suggested significantly greater improvement in the treatment versus the control groups in the short‐term and medium‐term. Effect sizes increased in long‐term follow‐up, but some of these effects did not reach statistical significance. A relatively small number of studies (N < 20) contributed data for the outcome categories. There was also significant heterogeneity between studies in most categories, possibly due to observed differences between manualised versus non‐manualised treatments, short versus longer treatments, studies with observer‐rated versus self report outcomes, and studies employing different treatment models.

Authors' conclusions

There has been further study of STPP and it continues to show promise, with modest to large gains for a wide variety of people. However, given the limited data, loss of significance in some measures at long‐term follow‐up and heterogeneity between studies, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, variability in treatment delivery and treatment quality may limit the reliability of estimates of effect for STPP. Larger studies of higher quality and with specific diagnoses are warranted.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Mental Disorders; Mental Disorders/therapy; Psychotherapy, Brief; Psychotherapy, Brief/methods; Psychotherapy, Psychodynamic; Psychotherapy, Psychodynamic/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Somatoform Disorders; Somatoform Disorders/therapy

Plain language summary

Short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders

Background

Common mental disorders include anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, stress‐related physical conditions, certain behaviour disorders and personality disorders. People with these disorders tend to have problems handling difficult emotions and often respond with physical and psychic symptoms or avoidant behavioural patterns. Such patterns and emotional responses are theoretically treatable by short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapies (STPP) because these therapies aim to improve long‐ and short‐term problems with emotion processing, behaviour and communication/relationships with others. STPP is thought to work by making people aware of emotions, thoughts and problems with communication/relationships that are related to past and recent trauma. This in turn helps to correct problems with emotions and relationships with others.

This review sought to find out whether STPP is more effective than wait‐list control (where people receive therapy after a delay during which people in the 'active' group receive the therapy), treatment as usual and minimal treatment (partial treatments not expected to provide a robust effect).

Study characteristics

We searched scientific databases to find all published and unpublished studies of STPP compared with wait‐list control, treatment as usual or minimal treatment up to July 2012. We searched for studies in adults over 17 years of age with common mental disorders being treated in an outpatient setting. We excluded people with psychotic disorders.

Key results

We included 33 studies involving 2173 people. When the results of the studies were combined and analysed, we found that there was a significantly greater improvement in the groups of people who received STPP versus the control groups, both in the short‐term (less than three months after treatment) and medium‐term (three to six months after treatment). These benefits generally appeared to increase in the long‐term. However, some results did not remain statistically significant in the long‐term and, in addition, the studies varied in terms of their design, meaning that these conclusions are tentative and need confirmation with further research. The finding that a short‐term psychological therapy treatment may be broadly applicable and effective is of importance in the atmosphere of current global healthcare and economic restrictions.

Quality of the evidence

The studies were of variable quality.

Background

Description of the condition

Common mental disorders (CMD) are the range of non‐psychotic symptom and behaviour disorders frequently seen in primary care and psychiatry services. They include depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders and other conditions often mixed with interpersonal or personality disorders. These are extremely common conditions, with 12‐month prevalences of 6.9% for depression, 14.0% for anxiety disorders and 6.3% for somatoform disorders in one European review (Wittchen 2011). Collectively, they produce great expense to society and personal suffering for those people afflicted (Lazar 2010). Treatment guidelines for these conditions commonly cite the use of psychological therapy alongside medication as front‐line treatment options. Psychotherapies have established effectiveness in some of these conditions. Medications such as antidepressants are frequently used and, although there is some controversy about the magnitude of their effectiveness in real world samples, these appear to be marginally superior to (non‐active) placebo controls in short‐term randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for many of these conditions.

People with such a broad range of CMDs present to physicians, hospitals and mental health services. Common treatment options in these settings include psychotherapy (e.g. psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapies), medications and, in certain situations such as severe depression, procedures such as electroconvulsive therapy.

Description of the intervention

Short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) has been developed since the mid‐1970s by a number of proponents including James Mann (Mann 1973), David Malan (Malan 1979), Habib Davanloo (Davanloo 2000), Peter Sifneos (Sifneos 1972), Hans Strupp and Jeffrey Binder (Strupp 1984), and Lester Luborsky (Luborsky 1984), as brief alternatives to the prior long‐term psychodynamic therapy models. These treatments are brief talking therapies developed to work with unconscious impulses, feelings and processes that can underpin or perpetuate CMDs. Such unconscious impulses, feelings and processes often relate to losses or traumatising events in the past. Such adverse events are known risk factors for self destructive behaviours, multiple CMDs and multiple somatic disorders (Felitti 1998). Thus, psychodynamic psychotherapy, with its focus on resolving old trauma and its damaging effects on relationships, is used to treat multiple conditions including CMD (Leichsenring 2014; Shedler 2010).

Psychodynamic psychotherapy has common factors outlined by Blagys and Hilsenroth including: focus on affect and expression of emotion, exploration of attempts to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings, identification of recurring themes and patterns, discussion of past experience, focus on interpersonal relations, focus on the therapy relationship and exploration of wishes and fantasies (Blagys 2000). These features can reliably distinguish psychodynamic therapy from other models such as cognitive therapy (Blagys 2000).

In addition to these factors, elements that distinguish STPP from long‐term psychodynamic treatments include the use of selection criteria, time restriction, selection of and adherence to a therapeutic focus, efforts to prevent regression, high degrees of therapist activity and active focus on the transference (therapeutic) relationship as a template to learn about and activate emotional‐relational processes. Some models use a strict time limited format (e.g. Mann 1973), while others do not (Davanloo 2000), but the within‐study mean number of sessions is typically 12 to 24 with a range of four to 40 weekly sessions. The sessions are face‐to‐face and generally 45 to 60 minutes weekly. Many STPP methods use the triangle of conflict (the link between feelings, anxiety and defence) and the triangle of person (the link between past, therapist and current people) as key linkages to examine in the therapeutic process (Davanloo 1980;Malan 1979).

STPP treatment efforts include interventions falling along a continuum between 'supportive' (such as reassurance and encouragement) and 'expressive' elements (such as challenge to defences and elicitation of emotions) (Luborsky 1984). They may also be more or less focused on emotional mobilisation and experiencing versus insight into processes. Some models include a process to build anxiety tolerance through graded exposure to unconscious anxiety, feelings and impulses (Davanloo 2000). Hence, models of STPP can be used with people who may otherwise be unable to tolerate an emotion‐focused treatment. This includes people with active major depression or somatisation and people who use projective defences and dissociation. Hence, these models (e.g. Davanloo 2000; Luborsky 1984; McCullough 2003) can be used with a broad range of people with personality disorder including borderline personality disorder (Town 2011), and a range of depressive (Abbass 2010; Driessen 2010), and somatic disorders (Abbass 2009).

In the early phase of STPP development, case‐based research showed that a range of people could be successfully treated by these brief therapies, and that the gains were maintained at follow‐up (Davanloo 1980; Malan 1979; Mann 1973; Sifneos 1972). Since the 1980s, other STPP models have, and continue to be, developed. Some are more focused on various aspects of these above‐noted common processes. For example, one well‐studied model, psychodynamic interpersonal therapy (PIT), which was developed based on the Hobson model (Hobson 1985), emphasises interpersonal problems and the use of the therapy relationship as a means of understanding and changing these problematic patterns. A second model, intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy, is an emotion‐focused model developed by Davanloo (Davanloo 2000) and Malan (Malan 1986) with the expressed purpose of treating complex and resistant populations. Twenty‐one studies of this model were reviewed revealing large within‐ and between‐group (cases versus controls) effects across a broad range of populations (Abbass 2012) and specifically for personality and somatic disorders (Town 2013). Luborsky's technique (Luborsky 1984), supportive‐expressive therapy, operationalises and focuses on conflict through the examination of core conflictual relationship themes. Affect phobia therapy (McCullough 2003), influenced by Davanloo's model, focuses on exposure to feared affect warded off by defence mechanisms that are associated with symptoms and personality disorder (Svartberg 2004). Milrod and colleagues have developed and studied panic‐focused psychodynamic psychotherapy (Milrod 2007), and Monsen 2000 developed psychodynamic body therapy. Other new STPP models include dynamic interpersonal therapy (Lemma 2010), a time‐limited treatment for anxiety and depression.

How the intervention might work

STPP is a form of psychodynamic therapy and, thus, its mechanisms of action parallel that of psychodynamic therapy overall (Blagys 2000; Shedler 2010). These mechanisms include facilitation of a therapeutic alliance, building emotional capacities, building self awareness, emotional work to heal past wounds and an interpersonally corrective experience.

In terms of key processes, STPP is purported to work by engaging the person to recognise and relinquish intrapsychic and interpersonal patterns that interrupt the processing and working through of anxiety‐laden past and current experiences. The therapy relationship is used as vehicle to promote change. It is seen to provide both a window to access unprocessed emotions related to past relationships, and as an in vivo interpersonal context in which to learn how to respond adaptively to these unprocessed emotions (Shedler 2010). Helping a person see the connections between past/current and therapeutic relationships plus feelings/impulses/anxiety and defences brings insight on how emotions activate unconscious reactions and how the past and present are intertwined in the unconscious mind. Healing may take place through the emergence of new understanding about the impact of these often previously implicit processes associated with emotional trauma. The extent to which this involves emotional as well as intellectual neural structures may point to the nature and relative degree of therapeutic change (Diener 2007; Ulvenes 2012). Long‐lasting and sustained improvement in quality of life and interpersonal relationships, as well as symptom reduction, are presumed to be associated with the healthy adaptation of previously negative internal representations of the self and other. Common results from this work include improved awareness of emotions, awareness of and changes in interpersonal patterns, and improved capacity to tolerate both interactions and emotions. So overall, combinations of building insight, interpersonal corrective experiences with the therapist and emotional processing appear key treatment factors.

The STPP therapist uses a range of interventions to facilitate the therapeutic alliance. In STPP, the therapeutic alliance is mobilised through, in addition to other elements, efforts to help the person face difficult emotions, clarification of observed repeated defensive patterns and challenge to emotional avoidance in the therapeutic relationship (Davanloo 1980; Luborsky 1984). These efforts activate conscious and unconscious drives in the person to be aware of and address hitherto avoided emotions: these healing forces are what comprise the therapeutic alliance contributions of the person. Recapitulation and interpretation of what is discovered is employed to help cement learning and foster a stronger therapeutic alliance (Davanloo 2000; Messer 1995). This alliance appears to be a strong contributor to outcomes across many forms of psychotherapy.

Some STPP models are more supportive than confrontative of defences. Some are more reliant on developing insight into repeated patterns (Luborsky 1984), while others rely more on defence handling and emotional mobilisation (e.g. Davanloo 2000; McCullough 2003). Most models and therapists are likely to use combinations of supportive/confrontative techniques and interpretation/emotion mobilisation in line with patient in‐session response and presentation (Luborsky 1984; Messer 1995).

As noted, the treatment course is relatively brief averaging 12 to 24 sessions, although some treatment courses will extend up to 40 sessions when working with people with more severe emotional dysregulation, limited anxiety tolerance and depression. Working through of emotions and conflict takes place over a series of sessions followed by a phase of termination. At termination, emotions related to past losses are generally activated and worked through (Mann 1973; Messer 1995).

STPP may be provided in combination with medication such as antidepressants, especially where first‐line psychotherapy or medication alone were not adequately effective (Malhi 2009). Some reviews have suggested that combination treatments are more effective than either medication or psychotherapy alone, for example in the treatment of chronic depression (Malhi 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

When we published this original review (Abbass 2006), we estimated that there were over 50 studies of STPP published in the English language literature and that the mix of results from early meta‐analyses made a call for a formal review of this evidence base using Cochrane methodology. Since then, many more studies have been published along with a series of meta‐analyses (e.g. Abbass 2009; Abbass 2010; Abbass 2011; Driessen 2010; Town 2011; Town 2012). Conservatively, there are now over 100 published trials of STPP reviewed in over 12 meta‐analyses. These individual studies are of a broad range of psychological and medical conditions and with a range of controls and research methodologies. Furthermore, recent research shows that psychodynamic therapy is frequently used in clinical practice (Cook 2010; Norcross 2013). Hence, it is important to update this Cochrane review to clarify the current state of evidence of STPP for CMDs.

While early meta‐analyses have yielded differing results due to differences in methodology (Anderson 1995; Crits‐Christoph 1992;Svartberg 1991), more recent reviews have generally reported large effects sustained or increasing over time within group while studying RCTs and non‐RCTs. Heterogeneity has been high in many studies and not all results were maintained in subgroup analyses suggesting a cautious interpretation is required. None of these reviews employed a methodology similar to ours including the entire cluster of CMDs versus all non‐formal psychotherapy or wait‐list controls.

Thus, we present this updated Cochrane review of these treatment approaches compared with non‐treatment and minimal treatment controls for people with CMDs.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of STPP for adults with CMDs compared with wait‐list controls, treatments as usual and minimal contact controls in RCTs. To specify the differential effects of STPP for people with different disorders (e.g. depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, mixed disorders and personality disorder) and treatment characteristics (e.g. manualised versus non‐manualised therapies).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs of STPP treatments. Cluster randomised trials and cross‐over randomised trials were eligible.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Adults (i.e. over 17 years old).

Diagnosis

We reviewed the following CMDs (among others), anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, somatoform disorders, certain behaviour disorders (such as eating disorder, self injurious behaviour) and interpersonal or personality problems mixed with symptom disorders.

Co‐morbidities

We accepted studies with medical or psychiatric co‐morbidity, including personality disorder.

We excluded studies of people with psychotic disorders.

Setting

We limited the population to outpatients.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

We defined STPP as:

at least one treatment group as psychodynamic in nature and treatment lasted 40 weeks or less on average.

treatment was 40 or fewer sessions, as this is the definition used in previous meta‐analyses;

the treatment technique was derived from the work of one or more developers of STPPs such as Malan (Malan 1979), Davanloo (Davanloo 1980), or Luborsky (Luborsky 1984), or was specifically developed and described for a brief psychodynamic approach;

the treatment under investigation was given in an individual format; and

the treatment had standard length sessions of 45 to 60 minutes.

Control interventions

We included studies in which controls were those conditions other than robust, bona fide psychological therapy treatments for the condition studied. These included:

wait‐list controls;

minimal treatment controls that had been designed as psychological 'placebo treatments'. For example these may have included short supportive conversations each month, the provision of psycho‐education, or partial treatments not expected to provide a robust psychotherapy effect;

treatments as usual including, for example, medical treatment as usual and psychiatric care as usual; and

studies in which non‐psychotherapeutic treatments (such as medications or medical care as usual) were provided equally in both arms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. General symptoms as defined by standardised psychiatric instruments or criteria (e.g. Symptom Checklist 90; Derogatis 1994).

2. Somatic symptoms (e.g. McGill Pain Questionnaire; Melzack 1975).

3. Anxiety (e.g. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; Hamilton 1959).

4. Depression (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); Beck 1961).

Secondary outcomes

5. Social adjustment (e.g. the Social Adjustment Scale; Weissman 1978).

6. Quality of life (e.g. EuroQol; EuroQol 1990).

7. Behavioural measures (e.g. attempts at self harm).

8. Interpersonal problem measures (e.g. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems; Horowitz 1988).

9. Patient satisfaction as measured by standardised instruments.

10. Health service use (e.g. hospital admission, outpatient contacts, visits to primary care).

11. Cost measures (e.g. medication cost changes).

12. Death.

13. Dropout rates.

14. Occupational functioning.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

When more than one scale was used to measure similar elements or the same element (e.g. depression), we used the following approach:

blind observer rated measures were used over self reported measures;

well‐known, validated measures were used ahead of lesser known, not well‐validated measures;

measures covering the scope of a condition were used ahead of measures covering only part of a condition (e.g. BDI versus Beck Hopelessness Scale: hopelessness is only one part of depression and is covered in the BDI so the BDI is used);

the measure designated as the a priori primary outcome measure was used over what was an a priori designated secondary outcome measure.

We solved cases of any disagreement between evaluators through consensus or eliciting the opinion of a third rater.

Timing of outcome assessment

Where sufficient data were available, we studied treatment outcomes in three time frames:

short‐term: less than three months after treatment was concluded;

medium‐term: three to nine months after treatment was concluded;

long‐term: nine or more months after treatment is completed.

When there were multiple measurement points inside one time frame, we used data from the longest follow‐up assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK, a references register and a studies based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 34,000 reports of randomized controlled trials in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Coordinator for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), EMBASE (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organisation’s trials portal (ICTRP), ClinicalTrials.gov, drug companies, the hand‐searching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies can be found on the Group‘s website.

Electronic searches

1. The Cochrane, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The CCDANCTR was searched by the Group's Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) to February 2010 using a sensitive list of terms for psychodynamic psychotherapies (intervention only). An update search was conducted in February 2014 using a more precision maximazing search strategy (intervention + comparator). A companion search of PsycINFO was also conducted at this time.

CCDANCTR (Studies and References Register, update search 2014‐02‐21): #1 (psychoanalytic or psychodynamic* or psycho‐dynamic* or (*dynamic* and (brief or *psycho* or *therap*)) or "time limited psychotherap*" or mann's or davanloo* or hobson* or STPP or ISTDP):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #2 ("treatment as usual" or tau:ab or "usual care" or "care as usual" or waitlist* or "wait* list*" or wait‐list* or "minim* contact*") #3 (enhanced or routine or standard or traditional or usual) NEAR2 (*care or treatment or *therap*) #4 (delay* or “no treatment” or “no *therap*”) NEAR (control or group or treatment*) #5 (peer or “self help*” or “mutual help*” or (support* NEAR2 (“help” or group or *therap* or listening)) or relaxation) #6 (“combined modality” or (combin* NEAR2 (therapy or treatment))) #7 (#1 and (#2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6))

OVID PsycINFO (update search 2014‐02‐21): 1. PSYCHODYNAMICS/ 2. PSYCHODYNAMIC PSYCHOTHERAPY/ 3. (psychodynamic* and (therapy or psychotherapy)).ti,ab. 4. ((brief adj3 dynamic) and (therapy or psychotherapy)).ti,ab. 5. (dynamic* adj3 (therapy or psychotherapy)).ti,ab. 6. or/1‐5 7. (randomized or randomised).ti,ab,sh. 8. (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or control* or determine* or divide* or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or recruit* or subsitut* or treat*)).ab. 9. or/7‐8 10. 6 and 9 PsycINFO records were screened and added to the CCDANCTR as appropriate.

CCDANCTR (Studies and References Register, initial search, all years to 2010‐02‐03): Studies Register: Intervention = (Psychodynamic or Dynamic or Psychoanalytic or Analytic) and Age Group = (Adult or Aged) References Register: Free‐Text = Psychodynamic or Dynamic or Psychoanalytic or Analytic

2.Other electronic searches To ensure all eligible studies and review articles were identified, we conducted our own searches on the following electronic databases (2012‐07‐23): The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE (1966‐); EMBASE (1980‐), CINAHL (1982‐), PsycINFO (1887‐ ), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) and Biological Abstracts (January 1980‐). The search strategy included terms for common mental health disorders and brief/time limited psychodynamic psychotherapies, see CENTRAL search (Appendix 1).

For MEDLINE, we expanded the search to include ANALYTIC, PSYCHOANALYTIC, DYNAMIC or PSYCHODYNAMIC, as the National Library of Medicine has defined brief psychotherapy as being not more than 20 sessions for indexing purposes since 1973. This ensured we did not miss therapies of up to 40 sessions.

No restrictions on date, language or publication status were applied to the searches. All relevant foreign language papers were translated.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all retrieved and potentially relevant papers, as well as relevant systematic reviews and literature reviews to identify other potentially relevant articles. We retrieved and assessed these articles for possible inclusion in the review.

Personal communications

We wrote to the lead author of relevant studies to ascertain if they knew of any additional related published or unpublished data that may have been relevant to the review. We contacted two list serves containing psychodynamic researchers to ask about recent studies.

Handsearching

We scrutinised abstracts from national and international psychiatry and psychology conferences to identify unpublished studies. These included meetings organised by national and international medical colleges, speciality societies and professional organisations. We contacted the authors of these studies to obtain further details about the studies and to enquire if they knew of any other unpublished or published relevant work.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors independently selected suitable studies for inclusion in this review as detailed below. Where the two review authors disagreed about the inclusion of a study, we resolved disagreements by consensus, and consulted a third author if they could not reach consensus. Where resolution was not possible, we contacted the investigator to obtain more information and clarification.

We assessed the titles and abstracts of studies identified by searching electronic databases to determine whether each article met the eligibility criteria. In order to limit bias, we printed out a list of all titles and abstracts excluding the investigators' names, institutions and journal title. If the title and abstract contained sufficient information to determine that an article did not meet the inclusion criteria, we rejected that article. We documented all rejected papers and the reasons for rejection.

We retrieved the full papers of all remaining titles and abstracts deemed relevant. In addition, we reviewed all other potentially relevant articles identified by the various search strategies (reference checking, personal communications, etc.). We translated all papers in languages other than English or someone competent in that language reviewed them.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently reviewed all articles, each of whom completed a form for each study and made a judgement on the quality using the 'Risk of bias' tools defined below. We documented the reasons for exclusion. Where the same study had more than one article written about the outcomes, we treated all articles as one study and presented the results only once.

Data extraction

We extracted data from the papers and recorded them on forms to elicit the following information:

general (published/unpublished, title, authors, source, contact address, country, language of publication, year of publication, duplicate publications);

interventions (frequency, timing, individual versus group, up to 20 sessions versus 20 to 40 sessions, manual driven versus non‐manualised therapies), comparison interventions, concurrent medications;

participant characteristics ‐ sampling, exclusion criteria, number of participants, age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, educational status, duration of symptoms, number of complications, similarity of groups at baseline (including any co‐morbidity), withdrawals/losses to follow‐up (reasons/descriptions);

primary diagnosis (e.g. depression, anxiety or somatoform disorders). These were determined based on the reported diagnoses being treated in the paper independent of which diagnostic criteria were being used (e.g. Feighner Criteria or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) for major depression were both considered as depression);

type of medical co‐morbidity if present;

type of psychiatric co‐morbidity ‐ clinical diagnosis or symptomatology assessed by questionnaire;

type of outcome ‐ self report or observer‐rated;

type of assessment tool used to assess psychiatric co‐morbidity (e.g. BDI, Zung Depression Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Structured interview, DSM‐IV criteria;

cut‐off used on psychiatric scale, percentage of people defined as psychiatric cases on this basis; mean (standard deviation (SD)) symptom score;

timing of follow‐up: short‐term (less than three months), medium‐term (three to nine months) and long‐term (more than nine months);

assessment of different domains of bias according to the 'Risk of bias' tool defined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008b).

We reported a summary of data extracted from included studies.

Main planned comparisons

STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the current update of this review, we have updated the methods to include assessment for 'Risk of bias' based on the revised version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 8.5.1; Higgins 2008b). For each included study, two review authors assessed the degree to which:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated (random sequence generation);

the allocation was adequately concealed (allocation concealment);

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study (blinding);

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting; and

the study was apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias.

We allocated each domain one of three possible categories for each of the included studies: low risk of bias, high risk of bias and unclear risk of bias (where the risk of bias was uncertain or unknown).

We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving a third review author.

In future reviews, we will adapt the 'Risk of bias' tool to incorporate features such as the use of adherence ratings, the use of manuals, therapist experience, handling of participants lost to follow‐up and researcher allegiance to enable measurement of psychotherapy quality.

Measures of treatment effect

Many rating scales are available to measure outcomes in psychological trials. These scales vary in the quality of their validation and reliability. Therefore, if a rating scale's validation had not been published in a peer‐reviewed journal, then the data were not included in this review. In addition, the rating scale should have been either self report or completed by an independent observer or relative. Trials that used the same instrument to measure specific outcomes were used in direct comparisons where possible. We reported the mean and SD. Where SDs were not reported in the paper, we attempted to obtain them from the authors or to calculate them using others measures of variation that were reported, such as the confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, we meta‐analysed data from different scales, rating the same effect using the standardised mean difference (SMD). We considered SMDs of 0.2 as small, 0.5 as moderate and 0.8 and greater as large (Cohen 1988).

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

Due to the risk of carry‐over effects in cross‐over trials, we used only data from the first phase of the study.

Cluster‐randomised trials

Should any cluster randomised trials be identified in future updates of this review, we will include them as long as proper adjustment for the intra‐cluster correlation can be undertaken as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where studies had additional treatment arms that were not relevant to this review, we did not consider those additional data. If a study had more than two treatment arms that met the inclusion criteria (e.g. two brief psychodynamic psychotherapy models and a psychological placebo arm), then the data from the psychological placebo arm were split equally between to produce two (or more) pair wise comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

Where it was not possible to analyse data quantitatively as reported in published studies, we contacted the first author to obtain the additional data required. We used data from intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses where possible. We listed issues of attrition bias in the 'Risk of Bias' tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity on the basis of the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (I2 values of 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity). In addition to the I2 value (Higgins 2003), we presented the Chi2 and its P value and considered the direction and magnitude of the treatment effects. In a meta‐analysis with few studies, the Chi2 test is underpowered to detect heterogeneity should it exist, thus, we used a P value of 0.10 as a threshold of statistical significance. Hence, we consider P value < 0.10 and I2 of 50% or more to reflect significant heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We used data from all identified and selected trials to draw a funnel plot (size of study versus effect size) (Egger 1997), to attempt to detect the possibility of publication bias. However, it should be noted that there may be other reasons for asymmetry in funnel plots, such as heterogeneity and small‐study effects.

Data synthesis

If studies were available that were sufficiently similar and of sufficient quality, we pooled those that could be grouped together and used the statistical techniques of meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012). We used a fixed‐effect model when there was little statistical heterogeneity (both P value > 0.10 and I2 of 50% or greater). In cases where there was significant heterogeneity (both P value < 0.10 and I2 of 50% or greater), we used a random‐effects model. Thus, we relied on the results of these two measures to decide which model to report. The rationale for this decision was that, even though there were expectations of variation between studies (due to samples, treatment approaches and controls), within each subgroup (e.g. social adjustment, short‐term follow‐up) there was a possibility of low heterogeneity due to the measures, timing and groups using those measures (e.g. mostly studies of people with depression measuring depression). In cases where these measures of heterogeneity were not significant and we used a fixed‐effect model, we also examined the effects using a random‐effects model to determine if this decision had any bearing on outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In order to investigate sources of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses as follows:

studies using minimal treatment or wait‐list controls as opposed to treatment as usual as a comparator;

studies of therapy of up to 20 sessions versus over 20 sessions in duration;

studies of specific STPP methods when there were adequate numbers (five or more) of such studies; and

studies of different diagnostic groups including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, mixed disorders and personality disorder.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses examining treatment effects of the following groups of studies in comparison with those of the entire group of studies:

manualised therapies only;

studies giving observer‐rated outcome;

studies with medications provided on both study arms.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

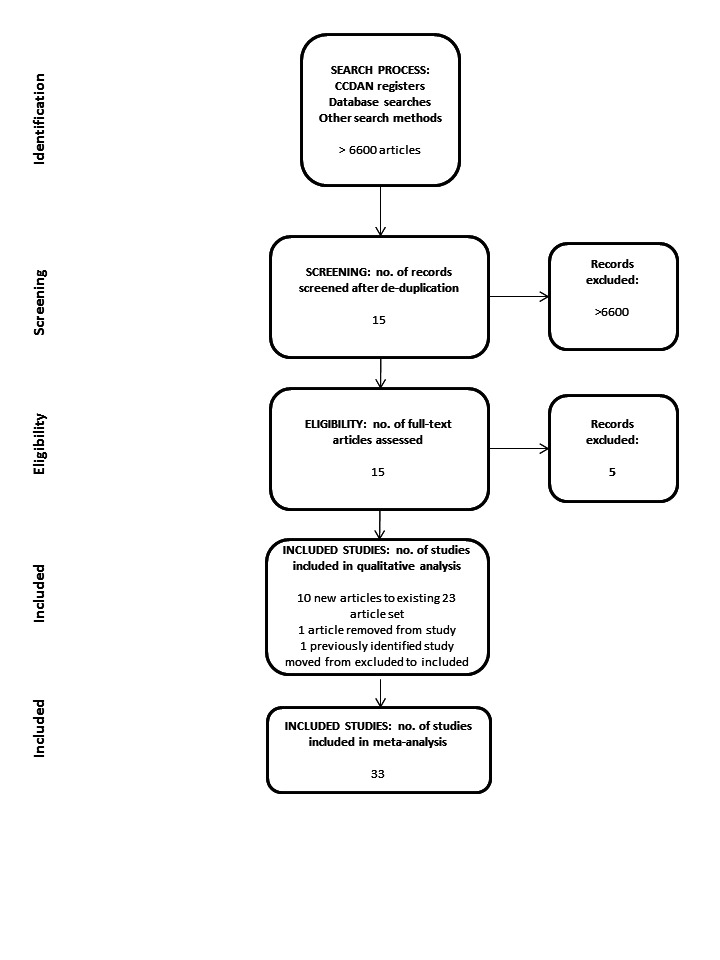

We carried out update searches to 23 July 2012. These broad searches identified more than 6800 references. It is likely many of these overlapped with the large set of studies reviewed for this original review (Abbass 2006). We excluded all but 18 from assessment of title and abstract. Fifteen remained after de‐duplication. We retrieved full papers for these 15 records. After inspection of the full‐text papers, we excluded five records. The remaining 10 references were added to those from the earlier version of this review and they contributed to the analysis (Characteristics of included studies).

In this updated version of the review, Dare 2001 was moved from the excluded studies to the included studies, in accordance with Cochrane's MECIR standards (Chandler 2013), which states that eligible studies be included irrespective of whether measured outcome data has been reported in a 'useable' way.

The study selection process is also detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

A late‐stage literature search was conducted by the Cochrane, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (February 2014) and publications to be considered for inclusion in the next update of this review are listed (for the reader's benefits) in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification .

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

All 33 studies included were RCTs. We found several cross‐over trials but no cluster randomised trials.

Sample sizes

The mean number of randomised participants was 65.3 with nearly all samples containing between 30 and 80 participants.

Setting

All studies were conducted in outpatient settings. Studies were conducted in several countries primarily in Europe and North America.

Participants

All studies were of adult samples. Six studies included only female participants (Alstrom 1984b; Baldoni 1995; Carrington 1979; Cooper 2003; Marmar 1988; Vitriol 2009), and almost all of the studies had a majority of females. Primary problems were diverse and included somatoform disorders (eight studies), mixed conditions (eight studies), anxiety disorders (seven studies), depressive disorders (five studies), personality disorders (three studies), self induced poisoning (one study) and eating disorders (one study). The somatoform disorders included multisomatoform disorder, irritable bowel syndrome (three studies), chronic pain, urethral syndrome, pelvic pain, chronic dyspepsia and atopic dermatitis. Anxiety disorders included obsessive‐compulsive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, hypochondriasis, agoraphobia, social phobia, panic disorder and post‐traumatic stress disorder.

Over one‐third of these studies included challenging‐to‐treat populations. Three studies included people with co‐morbid personality disorders among their samples or as the main study sample (Abbass 2008; Emmelkamp 2006;Winston 1994). One study included people with deliberate self poisoning (Guthrie 2001). Several studies were of 'treatment resistant' (Guthrie 1993), 'high utilizers' (Guthrie 1999), 'chronic' (Hamilton 2000), or 'severe' (Creed 2003; Sattel 2012; Vitriol 2009) populations, while two included participants who were not candidates for a traditional psychoanalytic treatment (Alstrom 1984a;Alstrom 1984b).

Interventions

A range of brief psychodynamic‐based psychotherapy methods were represented in these studies. Eleven cited Davanloo/Malan's model (Davanloo 1980;Malan 1979), while six cited PIT derived from Hobson 1985. These courses of therapy averaged 15.0 psychodynamic therapy sessions (SD 8.9, range 4 to 40). They were described as employing common factors of brief dynamic therapies such as focus on unconscious operations and emotions, and their link to symptoms or behavioural problems. All but one study described the use of some brief therapy framework, while two studies had a general psychoanalytic model of short duration (Cooper 2003; Sloane 1975). Fourteen of these studies described using experienced therapists, but it was often unclear whether the therapists were experienced in the specific brief therapy approach versus other psychotherapy models. Fifteen studies referred to specific manuals while others referenced models including those of Davanloo 1980; Malan 1979;Mann 1973; and Strupp 1984. Because we did not exclude studies with medication use on both treatment arms, we included five such studies (Burnand 2002;de Jonghe 2001;Maina 2010;Vitriol 2009; Wiborg 1996). These five studies included people with depression, panic disorder and mixed disorders: participants were provided medications including clomipramine (two studies), other antidepressants (two studies) and psychotropic agents (one study) according to an algorithm from antidepressants to antipsychotics.

A range of controls was employed in these studies. Eighteen studies had treatment as usual, which included medications, medical management and, in some cases, psychotherapeutic support that did not constitute a robust treatment effort. Ten studies had wait‐list controls, often with cross‐over designs where participants received STPP after the wait list. Five studies had minimal psychological interventions used as controls. Overall, treatment as usual control situations provided less face‐to‐face therapist contact time than the STPP groups, although these were considered standard treatment approaches with presumed effectiveness. Fewer treatment benefits, due in part to less intense therapeutic exposures, would be expected in the wait list and minimal treatment controls versus controls with more robust treatments as usual including medication in many cases: for this reason, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with treatment as usual controls.

Outcomes

Nineteen studies reported on general psychiatric symptoms, 18 studies used measures of depression, 18 studies used measures of anxiety, eight studies used somatic symptom measures, six studies used interpersonal problem measures and nine studies used measures of social adjustment. Other measures were used only a few times or were not comparable enough to combine in this review.

Follow‐up periods varied from immediately post treatment up to four years (Baldoni 1995).

Excluded studies

We listed 22 studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Most studies examined in detail and ultimately excluded were studies that had other formal treatment controls. We excluded a study of ulcers that was included in the previous version of this review as it was conducted prior to the discovery of Helicobacter pylori and specific treatment of this (Sjodin 1986): thus, the care of ulcer disease has undergone major changes since this discovery. Other studies were not randomised trials.

Studies awaiting classification

There are 11 studies awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table). Three of these studies are of depression, three studies are of somatic symptom disorders and two studies are of anxiety disorders. Four of the studies are large with over 150 participants. Due to these large numbers and sets of studies inside of specific diagnostic categories, it is possible these studies may influence meta‐analytic outcomes.

New studies found at this update

We included 10 new trials in this update (Bressi 2010; Burnand 2002; Carrington 1979; Emmelkamp 2006; Levy Berg 2009; Maina 2010; Milrod 2007; Sattel 2012; Sørensen 2010; Vitriol 2009). Dare 2001 was moved from the excluded studies to the included studies, in accordance with The Cochrane Collaboration's methodological stipulation that studies that meet the inclusion criteria should be included in the review irrespective of whether they reported data in a useable way (Chandler 2013).

Ongoing studies

We have identified three ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). One of these is an RCT of intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy versus medical care as usual for treatment‐refractory depression (NCT01141426). One is an RCT of intensive short‐term dynamic psychotherapy versus care as usual for medically unexplained symptoms in the emergency department (NCT02076867). One is an RCT of dynamic interpersonal therapy versus an enhanced wait list condition for major depression (ISRCTN38209986).

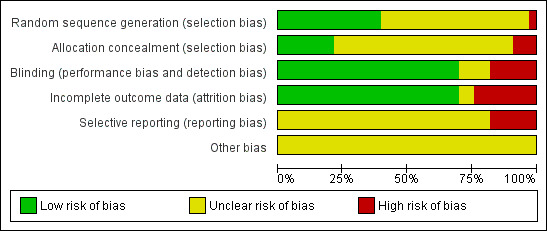

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the risk of bias judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies. Graphical representations of the overall risk of bias in included studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged only three of the 33 included studies to be at high risk of selection bias. However, for the majority of studies (19 out of 33 for selection bias (random sequence generation) and 23 out of 33 for selection bias (allocation concealment)), there was inadequate information to make a satisfactory risk of bias judgement.

Blinding

With self reported measures, blinding of the observer was less important. We judged the majority of studies (24 out of 33) to be of low risk of bias. For observer‐rated measures, we reported six studies as being at high risk of detection bias because raters were not blinded to treatment allocation group.

Incomplete outcome data

For the majority of studies (23 out of 33), we judged attrition bias to be at low risk of bias. We judged eight studies to be at high risk of bias and there was insufficient information to make an assessment for two studies. Studies classified as at high risk of attrition bias did not account for evident attrition in analyses.

To limit the influences of attrition bias, we only included studies with less than 20% drop‐outs but in the next iteration of this review, this will not be the case. Examination of the effects of the methods of handling of lost cases will be performed through risk of bias assessment and subgroup analyses.

Selective reporting

In six studies, we deemed there to be high risk of reporting bias. Without details of the study protocol, we deemed there to be insufficient information regarding reporting bias and therefore, we judged assessment of reporting bias to be unclear for the remaining studies.

Other potential sources of bias

For all studies, we judged risk of other sources of bias to be unclear due to insufficient information. One study employed a restricted STPP model where some key treatment ingredients were withheld for purposes of the study (Sørensen 2010).

Effects of interventions

We were able to combine results from studies for general psychiatric symptoms as well as anxiety disorders, depressive disorders and somatic symptoms. In each case, we have grouped findings under the following diagnostic groups: depression, anxiety, somatoform and mixed disorders. We highlighted any differences between groups in the section on subgroup analyses.

A few studies (e.g. Baldoni 1995;Creed 2003;Wiborg 1996 in general outcome measures) provided data at long‐term follow‐up but not at short‐term follow‐up in some outcome categories. Attrition data was lacking from or varied in definition in most papers so we reported only papers with self described dropout rates where they did statistical analyses and reported on it: we are considering a plan to extract/seek this data formally and report it in the next review.

Comparison 1. Short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapy versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment

Primary outcomes

There was significant heterogeneity (P values < 0.10, I2 = 50% or greater) in 10 of the 16 analyses. Therefore, we reported results derived from the random‐effects model for these comparisons. We reported results derived from the fixed‐effect model for the remaining analyses where measures of heterogeneity were not significant. These are illustrated in the Data and analyses table and figures. Given the frequency of significant heterogeneity in these analyses, in each study where a fixed‐effect model was reported, we also examined results using a random‐effects model: in each of the six cases, the differences were nil to negligible and there were no changes in statistical significance.

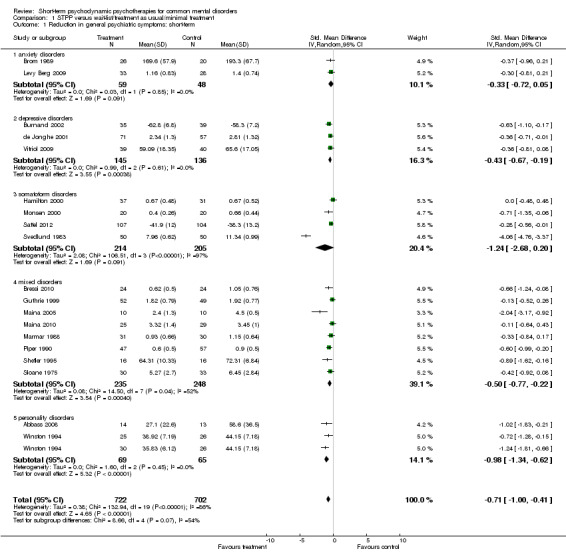

1.1 General symptoms as defined by standardised psychiatric instruments or criteria

We were able to incorporate 19 studies that reported measures of general psychiatric symptoms. We used the random‐effects model for short‐ and long‐term follow‐up, as there was significant heterogeneity and used the fixed‐effect model for medium‐term comparisons. These measures showed small to large differences in favour of STPP treatment.

The differences reached significance in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.41; 19 studies, 1424 participants) (Analysis 1.1) and medium‐term (SMD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.08; 5 studies, 437 participants) (Analysis 1.2). In the case of long‐term follow‐up, the effect sizes increased but marginally did not reach significance (SMD ‐1.51, 95% CI ‐3.14 to 0.12, P value = 0.07; 4 studies, 344 participants) (Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 1 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: short‐term.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 2 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: medium‐term.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 3 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: long‐term.

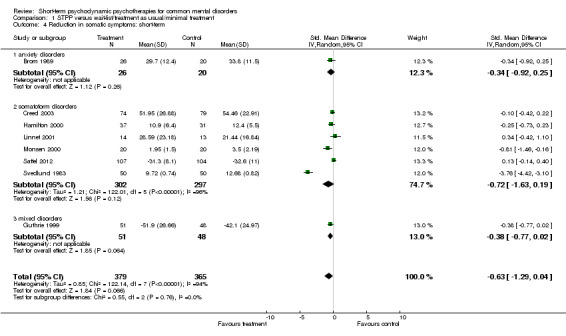

1.2 Somatic symptoms

We were able to incorporate eight studies that reported measures of somatic symptoms. We used the random‐effects model for short‐, medium‐ and long‐term follow‐up, as there was significant heterogeneity. These measures showed moderate to large differences in favour of STPP treatment.

The difference between treatment and control groups marginally did not reach statistical significance in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.63, 95% CI ‐1.29 to 0.04, P value = 0.07; 8 studies, 744 participants) (Analysis 1.4). The effects were significant in the medium‐term (SMD ‐1.39, 95% CI ‐2.75 to ‐0.02; 4 studies, 359 participants) (Analysis 1.5) but did not reach significance in long‐term follow‐up (SMD ‐2.21, 95% CI ‐5.49 to 1.07; 3 studies, 280 participants) (Analysis 1.6).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 4 Reduction in somatic symptoms: short‐term.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 5 Reduction in somatic symptoms: medium‐term.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 6 Reduction in somatic symptoms: long‐term.

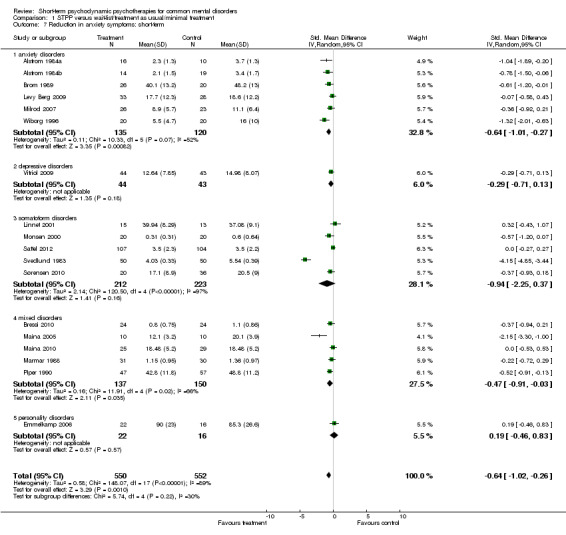

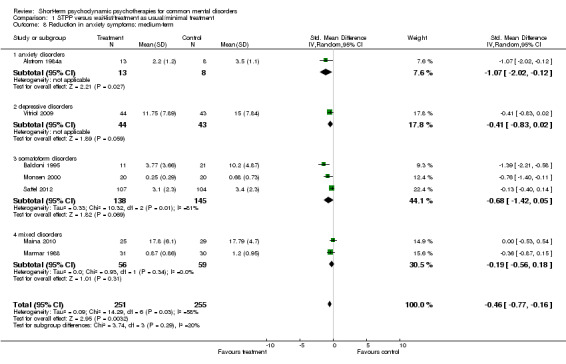

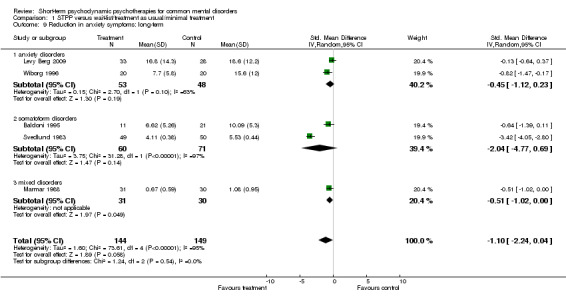

1.3 Anxiety

We were able to incorporate 18 studies that reported measures of anxiety symptoms. We used the random‐effects model for short‐, medium‐ and long‐term follow‐up, as there was significant heterogeneity. These measures showed modest to large differences in favour of STPP treatment.

The differences were statistically significant in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.64, 95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.26; 18 studies, 1102 participants) (Analysis 1.7) and medium‐term (SMD ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐0.77 to ‐0.16; 7 studies, 506 participants) (Analysis 1.8). In the long‐term follow‐up, these effects increased but marginally did not reach significance (SMD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐2.24 to 0.04, P value = 0.06; 5 studies, 293 participants) (Analysis 1.9).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 7 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: short‐term.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 8 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: medium‐term.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 9 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: long‐term.

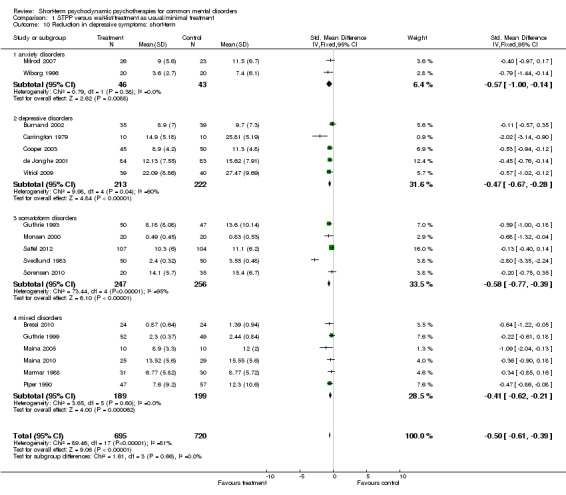

1.4 Depression

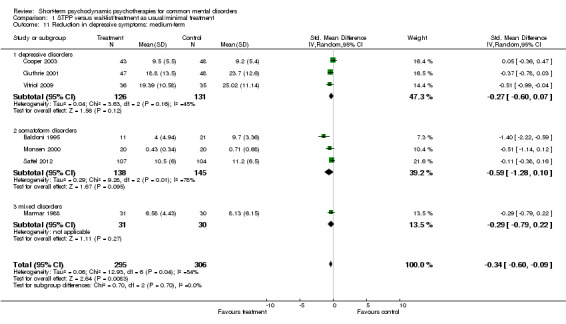

We were able to incorporate 18 studies that reported measures of depression symptoms. We used the random‐effects model for medium‐ and long‐term follow‐up, as there was significant heterogeneity and used the fixed‐effect model for short‐term comparisons.

Measures of depression showed small to medium and significant treatment effects relative to controls in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.39; 18 studies, 1415 participants) (Analysis 1.10) and the medium‐term (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.60 to ‐0.09; 7 studies, 601 participants) (Analysis 1.11). The effects increased but did not reach significance in long‐term follow‐up (SMD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐2.22 to 0.21; 5 studies, 321 participants) (Analysis 1.12).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 10 Reduction in depressive symptoms: short‐term.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 11 Reduction in depressive symptoms: medium‐term.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 12 Reduction in depressive symptoms: long‐term.

Secondary outcomes

In our protocol, we stated that we would consider secondary outcome measures including social adjustment, quality of life, behavioural measures, interpersonal problem measures and participant satisfaction as measured by standardised instruments. However, studies reported very different measures in insufficient detail for quantitative integration of data in most cases. In all cases, we used the fixed‐effect model, as tests for heterogeneity were non‐significant.

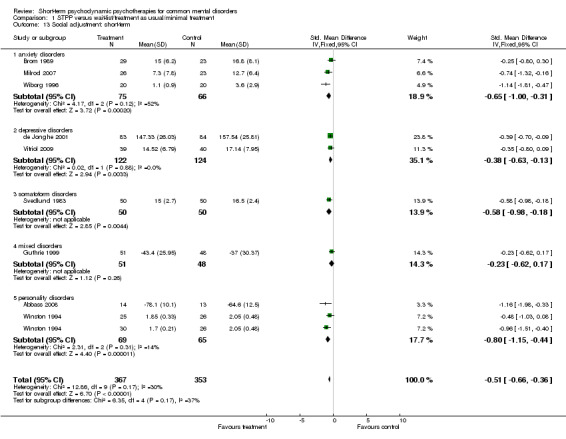

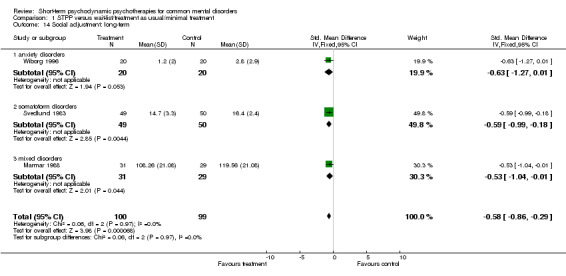

1.5 Social adjustment

Ten studies reported on social adjustment and showed significant and moderate effects in short‐term follow‐up using the fixed‐effect model (SMD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.36; 9 studies, 720 participants) (Analysis 1.13), which increased in long‐term follow‐up (SMD ‐0.58, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.29; 3 studies, 199 participants) (Analysis 1.14).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 13 Social adjustment: short‐term.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 14 Social adjustment: long‐term.

1.6 Quality of life

Guthrie 1999, using the EuroQol 5D, did not find significant differences at termination but did find significantly higher quality of life ratings in the STPP group in follow‐up. Creed 2003 found significant and persistent improvements on the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) physical scores relative to controls, but found significant superiority of STPP only in the short‐term on mental symptom subscales relative to controls. Levy Berg 2009 found greater improvement on the World Health Organization (WHO) Well Being Index in people receiving STPP with generalised anxiety disorder. de Jonghe 2001 reported greater gains on a measure of depression‐related quality of life in people who received combined STPP plus antidepressants versus antidepressant medication alone in the ITT sample.

1.7 Behavioural measures

In a unique and high‐quality study, Guthrie 2001 found treated participants had a reduction in suicidal ideation and self harm episodes relative to treatment as usual in people who had self induced poisoning. Dare 2001 found STPP to produce superior weight gains and recovery rates compared with controls in a group of adults with anorexia nervosa.

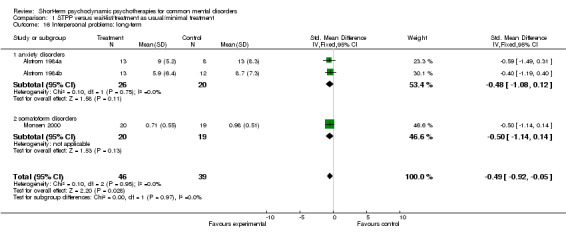

1.8 Interpersonal problem measures

Six studies reported outcomes on measures of interpersonal problems. Using the fixed‐effect model, significant effects were seen in the short‐term follow‐up (SMD ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐0.67 to ‐0.17; 6 studies, 265 participants) (Analysis 1.15), which increased in the long‐term follow‐up (SMD ‐0.49, 95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.05; 3 studies, 85 participants) (Analysis 1.16).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 15 Interpersonal problems: short‐term.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 STPP versus wait‐list/treatment as usual/minimal treatment, Outcome 16 Interpersonal problems: long‐term.

1.9 Participant satisfaction

Guthrie 2001 reported positive participant satisfaction measures after the six‐session treatment for deliberate self poisoning.

1.10 Health service use

Hamilton 2000 reported within‐group reduction in hospital, medication and service use but no differences between treatment and control groups. Burnand 2002 reported significantly fewer hospital admissions and days in people with depression provided STPP versus the treatment as usual control. Vitriol 2009 reported that severely depressed women with trauma histories treated with STPP had fewer hospital days (6 versus 21.3) but did not note if this was statistically different. Psychiatry use was greater in the STPP group (7 versus 2.5) as was psychologist use (5.7 versus 4.5 visits) in six‐month follow‐up. Guthrie 2001 reported no differences in healthcare use versus controls in follow‐up except treated participants with deliberate self poisoning saw psychiatric nurses more often. Sattel 2012 reported significantly less medication and psychotherapy use versus controls in follow‐up after STPP versus enhanced medical care for people with multisomatoform disorder: there were no differences in medical visits between the groups at any time point.

1.11 Cost measures

Creed 2003 found STPP was more cost effective than treatment as usual over the first year of treatment in people with irritable bowel syndrome, while paroxetine was not significantly more cost effective than control. Guthrie 1999 found STPP to reduce several cost measures significantly compared with treatment as usual in a mixed sample of high service‐utilising participants. Hamilton 2000 did not find significant cost savings relative to the control treatment but did note significant cost savings compared with the period before treatment. Burnand 2002 found significant cost savings beyond treatment costs of USD 2311 due to reduced hospital and disability costs: this is greater than controls but statistical analysis of the difference was not provided.

1.12 Mortality

No data were available for mortality.

1.13 Dropout rates

Two studies reported statistical analysis of differential dropout rates. de Jonghe 2001 specifically compared dropout rates between STPP added to treatment with medications versus medications alone. They found a 10% dropout rate using STPP plus medication versus 40% for medication alone. Milrod 2007 reported 7% drop‐out in the STPP group compared with 34% in treatment as usual, which was significantly different.

1.14 Occupational functioning

Monsen 2000 found those treated with STPP had significantly more job advancements and Creed 2003 found STPP‐treated participants had significantly less work disability compared with the paroxetine‐treated group. Abbass 2008 reported significantly more works hours and higher employment rates after STPP treatment versus the control condition in people with anxiety disorders. Alstrom found significantly superior improvement in work capacity relative to controls in the agoraphobic group (Alstrom 1984b), but not in the socially phobic group (Alstrom 1984a). Burnand 2002 reported significantly improved occupational functioning with fewer lost days due to disability.

Heterogeneity analysis

Tests for heterogeneity were statistically significant at the P value 0.10 or less and an I2 statistic of 50% or greater in 10 of the 16 cases. Heterogeneity was not significant for some subgroup analyses of the symptom most specific to the condition under consideration (e.g. medium‐term comparisons of depressive symptoms in depressive disorders). It was not significant in measures of social adjustment and interpersonal problems.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Because of the small number of trials in each analysis, these results are limited and should be interpreted with caution. Given the degree of heterogeneity expected in these analyses, we only present results using the random‐effects model. See Table 1 and Table 2.

1. Properties of studies.

| Study | Diagnosis | Manualised |

Observer rated |

Medication on both arms |

Wait‐list/ minimal treatment control |

20 or fewer sessions |

Malan/ Davanloo |

Hobson/ PIT |

| Abbass 2008 | Mixed: personality disorders | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Alstrom 1984a | Anxiety: social phobia | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Alstrom 1984b | Anxiety: agoraphobia | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Baldoni 1995 | Somatic/medical: urethral syndrome | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Bressi 2010 | Mixed: depressive and anxiety disorders | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Brom 1989 | Anxiety: PTSD | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Burnand 2002 | Depression: major depression | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Carrington 1979 | Depression: Feighner Criteria | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Cooper 2003 | Depression: postpartum depression | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Creed 2003 | Somatic/medical: IBS | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Dare 2001 | Anorexia nervosa | No | No | No | Yes | Yes/No | Yes | No |

| de Jonghe 2001 | Depression: major depression | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Emmelkamp 2006 | Mixed: personality disorders | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Guthrie 1993 | Somatic/medical: IBS | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Guthrie 1999 | Mixed diagnoses: general outpatient referrals | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Guthrie 2001 | Mixed diagnoses: self poisoning presenting to emergency | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hamilton 2000 | Somatic/medical: functional dyspepsia | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Levy Berg 2009 | Anxiety: generalised anxiety disorder | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Linnet 2001 | Somatic/medical: atopic dermatitis | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Maina 2005 | Mixed: mood and anxiety disorders | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Maina 2010 | Mixed: OCD and depression | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Marmar 1988 | Mixed: major depression, PTSD, adjustment disorders | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Milrod 2007 | Anxiety: panic disorder | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Monsen 2000 | Somatic/medical: pain syndromes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Piper 1990 | Mixed: mood, anxiety, adjustment, axis II | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sattel 2012 | Somatic/medical: multisomatoform disorders | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Shefler 1995 | Mixed: anxiety, depression, adjustment disorders | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Sloane 1975 | Mixed: 'psychoneuroses' and axis II | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Sørensen 2010 | Anxiety: hypochondriasis | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Svedlund 1983 | Somatic/medical: IBS | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Vitriol 2009 | Depression: severe major depression | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Wiborg 1996 | Anxiety: panic disorder | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Winston 1994 | Mixed: personality disorders | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

OCD: obsessive‐compulsive disorder; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; PIT: psychodynamic interpersonal therapy; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder.

2. Subgroup analyses.

| Outcome or subgroup |

Manualised (SMD (95% CI) |

Observer‐rated outcomes (SMD (95% CI) |

Medications on both arms (SMD (95% CI) |

Wait‐list or minimal treatment controls (SMD (95% CI) |

20 or fewer sessions (SMD (95% CI) |

Malan/ Davanloo (SMD (95% CI) |

Hobson/ PIT (SMD (95% CI) |

| 1.1 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: short‐term | ‐0.49 (‐0.72 to ‐0.27) | ‐0.87 (‐1.37 to ‐0.37) | ‐0.38 (‐0.59 to ‐0.16) | ‐0.67 (‐0.92 to ‐0.43) | ‐0.69 (‐1.08 to ‐0.30) | ‐1.28 (‐2.06 to ‐0.49) | ‐0.19 (‐0.39 to 0.01) |

| 1.2 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: medium‐term | ‐0.09 (‐0.34 to 0.15) | ‐0.37 (‐0.66 to ‐0.08) | ‐0.31 (‐0.66 to 0.04) | ‐0.50 (‐1.01 to 0.01) | ‐0.23 (‐0.44 to ‐0.02) | ‐0.11 (‐0.64 to 0.43) | ‐0.09 (‐0.36 to 0.18) |

| 1.3 Reduction in general psychiatric symptoms: long‐term | ‐0.44 (‐1.26 to 0.39) | ‐2.01 (‐4.29 to 0.27) | ‐0.91 (‐1.56 to ‐0.26) | ‐0.60 (‐1.11 to ‐0.08) | ‐1.51 (‐3.14 to 0.12) | ‐2.73 (‐6.30 to 0.84) | ‐0.06 (‐0.39 to 0.26) |

| 1.4 Reduction in somatic symptoms: short‐term | ‐0.11 (‐0.33 to 0.12) | ‐1.22 (‐3.62 to 1.17) | Not estimable | ‐0.34 (‐0.92 to 0.25) | ‐0.60 (‐1.34 to 0.13) | ‐1.71 (‐5.73 to 2.30) | ‐0.11 (‐0.33 to 0.12) |

| 1.5 Reduction in somatic symptoms: medium‐term | ‐1.91 (‐5.18 to 1.35) | Not estimable | Not estimable | Not estimable | ‐1.58 (‐3.56 to 0.39) | ‐0.94 (‐1.71 to ‐0.17) | ‐1.91 (‐5.18 to 1.35) |

| 1.6 Reduction in somatic symptoms: long‐term | 0.05 (‐0.27 to 0.37) | ‐6.61 (‐7.62 to ‐5.59) | Not estimable | Not estimable | ‐2.21 (‐5.49 to 1.07) | ‐3.38 (‐9.68 to 2.91) | 0.05 (‐0.27 to 0.37) |

| 1.7 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: short‐term | ‐0.45 (‐0.80 to ‐0.10) | ‐0.82 (‐1.43 to ‐0.21) | ‐0.50 (‐1.16 to 0.17) | ‐0.47 (‐0.74 to ‐0.20) | ‐0.74 (‐1.23 to ‐0.25) | ‐0.97 (‐1.90 to ‐0.05) | 0.00 (‐0.27 to 0.27) |

| 1.8 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: medium‐term | ‐0.10 (‐0.34 to 0.14) | ‐0.28 (‐0.56 to ‐0.01) | ‐0.24 (‐0.64 to 0.16) | ‐0.60 (‐1.26 to 0.06) | ‐0.57 (‐1.05 to ‐0.08) | ‐0.83 (‐2.45 to 0.79) | ‐0.13 (‐0.40 to 0.14) |

| 1.9 Reduction in anxiety symptoms: long‐term | ‐0.45 (‐1.12 to 0.23) | ‐1.58 (‐3.37 to 0.21) | ‐0.82 (‐1.47 to ‐0.17) | ‐0.32 (‐0.69 to 0.05) | ‐1.35 (‐2.73 to 0.03) | ‐1.64 (‐3.45 to 0.18) | Not estimable |

| 1.10 Reduction in depressive symptoms: short‐term | ‐0.56 (‐0.81 to ‐0.31) | ‐0.66 (‐0.99 to ‐0.32) | ‐0.43 (‐0.63 to ‐0.23) | ‐0.71 (‐1.20 to ‐0.22) | ‐0.68 (‐0.99 to ‐0.36) | ‐0.93 (‐1.16 to ‐0.70) | ‐0.26 (‐0.45 to ‐0.06) |

| 1.11 Reduction in depressive symptoms: medium‐term | ‐0.14 (‐0.34 to 0.07) | ‐0.57 (‐1.00 to ‐0.14) | ‐0.51 (‐0.99 to ‐0.04) | ‐0.29 (‐0.79 to 0.22) | ‐0.33 (‐0.61 to ‐0.05) | ‐1.40 (‐2.22 to ‐0.59) | ‐0.20 (‐0.44 to 0.04) |

| 1.12 Reduction in depressive symptoms: long‐term | ‐0.26 (‐0.93 to 0.41) | ‐0.41 (‐0.75 to ‐0.06) | ‐0.65 (‐1.29 to ‐0.01) | ‐0.35 (‐0.86 to 0.16) | ‐1.00 (‐2.22 to 0.21) | ‐1.59 (‐3.61 to 0.44) | Not estimable |

CI: confidence interval; PIT: psychodynamic interpersonal therapy; SMD: standardised mean difference.

Sensitivity analyses

a) Manualised therapies

When restricting analyses to studies using manualised treatments, there were smaller effects in most outcome categories compared with studies of the overall set of studies.

b) Studies that gave observer‐rated outcomes

The effect sizes were larger compared with those of the overall review studies in most outcome categories when analyses were restricted to studies that included observer ratings.

c) Studies that used medications on both treatment arms

When analyses were restricted to studies with medication on both treatment arms, effect sizes were generally smaller than the effects of the overall set of studies.

Subgroup analyses

a) Therapy of up to 20 sessions

When analyses were restricted to studies that averaged 20 or fewer sessions, measures of general symptoms in medium‐term, social adjustment and interpersonal problems were smaller compared with studies where treatment was over 20 sessions.

b) Studies that used minimal treatment or wait‐list controls as opposed to treatment as usual controls

Anxiety effect sizes were smaller when analyses were restricted to studies with minimal contact or wait‐list controls. Otherwise, there were no differences in degrees of significance or effect sizes compared with studies using treatment as usual controls.

c) Effects of short‐term psychodynamic psychotherapy treatment models

As a post hoc analysis, we examined outcomes by STPP treatment approach where five or more studies were available.

When analyses were restricted to models derived from Hobson or PIT (six studies), effects across all outcomes were smaller than studies using the Malan/Davanloo short‐term dynamic psychotherapy model (11 studies) with the exceptions of general symptoms at medium‐term and somatic symptom at medium‐term follow‐up. The effects of Hobson/PIT studies were negligible to small in all the other categories. In contrast, the effects of analyses restricted to Malan/Davanlo studies were large in all but general symptoms at medium‐term follow‐up.

d) Differences in outcomes between different diagnostic groups

People diagnosed with somatoform disorders had the greatest effects sizes in most outcome categories except general symptoms at medium‐term and somatic symptoms at medium‐term follow‐up. People diagnosed with depression tended to have the lowest effects on measures of anxiety and depression. See Data and analyses.

Assessing publication bias: funnel plot analysis

We explored funnel plots as an indication of publications bias. The largest number of studies available was in each of the short‐term outcome measures. Each of these had funnel plots that had some features of an inverted funnel (somatic) or had studies with similar standard errors (anxiety, depression), leaving a flat but dispersed distribution. Other categories had too few studies to allow an interpretation. Thus, we could not draw definitive conclusions about publication bias using this method.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This meta‐analysis of 33 RCTs of STPP comprised of 2173 participants found it to have modest to large effects relative to controls across a broad range of CMDs. With the exception of somatic measures in the short‐term, these effects were also statistically significant in short‐ and medium‐term follow‐ups while not reaching significance in long‐term follow‐up in some outcome categories. Benefits were observed across a broad range of outcome measures including general measures and somatic symptoms, as well as depression, anxiety, interpersonal and social adjustment. Individual studies also reported reduced self injury and weight gain in anorexia nervosa, suggesting behavioural as well as symptomatic gains. Studies also reported occupational gains and cost benefits. Combined, these findings provide converging evidence of treatment benefits. In each of somatic symptoms, depressive symptoms, anxiety, general symptoms, social adjustment and interpersonal problems, the treatment effect sizes were greater in long‐term follow‐up than in short‐term follow‐up suggesting accrued gains over time though some of this effect may have been from different studies reporting at different time intervals (i.e. short‐ versus long‐term follow‐up periods).

Study quality was variable in these studies, which spanned 1975 to 2012. Although STPP method (e.g. Hobson versus Malan/Davanloo) appeared to impact outcomes, it is yet to be determined if these effects are better accounted for by common (e.g. therapist training, adherence, allegiance effects) or specific (e.g. emotional experiencing, intellectual insight) factors. Heterogeneity and loss of significance of some measures in follow‐up suggest these results be interpreted with caution.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review found preliminary evidence that STPP may be effective for a broad range of CMDs as are seen in mental health and medical clinics. Common specific psychiatric conditions including major depression, somatic symptom disorders, eating disorders, anxiety disorders and personality disorders were treated in these studies.

Several studies included treatment resistant, severe and character‐disordered participants, which are challenging‐to‐treat patient groups. Treatment effects in these groups may be lower than what may be expected in samples without such resistance or complexity. Thus, these studies may underestimate the effects of this brief treatment. This is an important finding since these patient groups are common in clinical populations where half or more do not reach remission with first‐line psychotropic medication or talking therapies. These problems are costly to the system as they induce prolonged disability from work and excess hospital and medical service use, so, brief and relatively low‐cost treatment options are necessary and welcome.

The number of studies in many analyses was relatively small making comparisons across diagnostic groups and other subgroup analyses difficult. The diversity of the samples and treatment methods likely contributed to heterogeneity, which influences our ability to interpret these groups of studies. However, this diversity is also a strength of this literature implying the range of methods in STPP may be broadly applied in clinical populations.

Quality of the evidence

Study quality