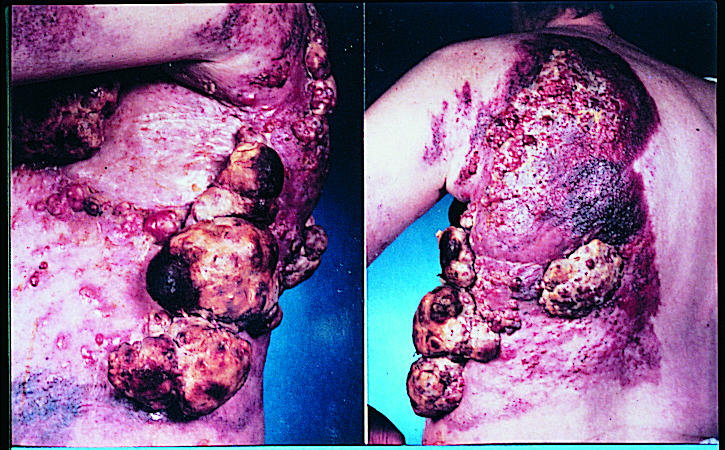

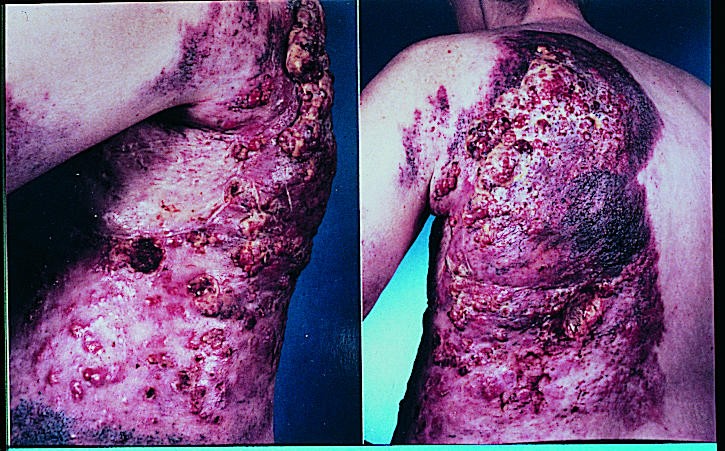

Editor—Regnard et al did not mention the use of 2% chlorhexidine mouth rinses in the section on mouth care and the risk factors for oral problems in their article in the ABC of Palliative Care.1 We have regular contact with groups of children with chronic disorders— for example, epidermolysis bullosa—and others who are treated with high dose chemotherapy and irradiation. One of the problems from which they suffer is severely blistered oral mucosa (children with epidermolysis bullosa) and mucositis related to chemotherapy or radiation.

The most widely investigated and used mouth care regimen is 2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse daily. Many workers have reported decreases in dental bacterial plaque and gingivitis.2,3 This leads to decreased oral bacterial loading, which is important, particularly in patients who are undergoing a period of immunosuppression as part of their treatment.4 Chlorhexidine does not greatly affect the progress of mucositis, and although the 7% ethanol base does cause a burning sensation, the antibacterial and local cleaning action are of great benefit to these patients. Although tooth brushing is the ideal oral hygiene method, most patients who are debilitated are unable to do this effectively and the mouth is not cleaned effectively. Mouth rinsing may also be difficult, and this difficulty can be easily overcome by soaking pink dressing sponges in chlorhexidine. When the teeth are closed on the sponges, the chlorhexidine is carried to the oral mucosa, gingivae, and teeth.

We believe that this logical approach to mouth care is more effective than the anecdotal remedies suggested by Regnard et al. Was the recommendation to use gin a misprint?

References

- 1.Regnard C, Allport S, Stephenson L. ABC of palliative care: Mouth care, skin care, and Iymphoedema. BMJ. 1997;315:1002–1005. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7114.1002. . (18 October.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiott CR, Loe H, Jensen SB, Kilian M, Davies RM, Glavind K. The effect of chlorhexidine mouthrinses on the human oral flora. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyston-Bechal S, Hernaman N. The effect of a mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine and fluoride on plaque and gingival bleeding. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferretti GA, Raybould TP, Brown AT, Macdonald JS, Greenwood M, Marnyama Y, et al. Chlorhexidine prophylaxis for chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced stomatitis: a randomised double-blind trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]