Abstract

We isolated a Bacillus subtilis natto strain, designated OK2, from a lot of commercial fermented soybean natto and studied its ability to undergo natural competence development using a comG-lacZ fusion at the amyE locus. Although transcription of the late competence genes was not detected in the B. subtilis natto strain OK2 during competence development, these genes were constitutively transcribed in the OK2 strain carrying either the mecA or the clpC mutation derived from B. subtilis 168. In addition, both OK2 mutants exhibited high transformation frequencies, comparable with that observed for B. subtilis 168. Moreover, as expected from these results, overproduction of ComK derived from strain 168 in strain OK2 resulted in a high transformation frequency as well as in induction of the late competence genes. These results clearly indicated that ComK produced in both the mecA and clpC mutants of strain OK2 (ComKOK2) could activate the transcription of the whole set of late competence genes and suggested that ComKOK2 was not activated in strain OK2 during competence development. We therefore sequenced the comS gene of OK2 and compared it with that of 168. The comSOK2 had a single-base change, resulting in the replacement of Ser (strain 168) by Cys (strain OK2) at position 11.

Some species of the genus Bacillus have been used not only for producing industrially useful exoenzymes, antibiotics, and insecticides, but also for making traditional foods such as natto, which is soybeans fermented by a Bacillus subtilis natto strain. Moreover, B. subtilis has been extensively studied because of its ability to sporulate as well as to be efficiently transformed. Based on its high natural transformability, B. subtilis has been utilized as a host bacterium for genetic engineering. The transformation system of B. subtilis is exquisitely regulated. During the development of natural genetic competence, the cells develop the ability to incorporate external DNA and to undergo homologous recombination between chromosomal and incoming single-stranded DNA (24). Among B. subtilis strains, the B. subtilis Marburg strain can be transformed at a high frequency, whereas other B. subtilis strains, including B. subtilis natto strains, give transformants at a frequency similar to that of spontaneous mutation.

The genome sequence of B. subtilis Marburg 168, which can develop competence, was completed in 1997 (15). Competence development in B. subtilis 168 is part of a complex signal transduction network influenced by the level of nutrients in the environment and by the cell density (3). The decisive step in the development of genetic competence is the synthesis of a transcriptional factor, ComK (3, 7, 9, 11, 28–30). The ComK protein in B. subtilis 168 can induce the transcription of recA as well as comK itself and all of the late competence operons (the comC gene and the comE, comF, and comG operons) that are essential for the uptake of exogenous DNA in macromolecular form (3, 7, 10). During the exponential-growth phase, ComK is inhibited by a direct protein-protein interaction with MecA and ClpC (14, 27). The bound ComK is also targeted for degradation by the ATP-dependent protease ClpCP (26). From the end of the exponential phase, ComS is synthesized as the end product of a quorum-sensing pathway. ComS causes the release of ComK from the ternary complex with ClpC and MecA, probably by altering the conformation of MecA and reducing its affinity for ComK (20). When ComS binds to MecA, the rate of ComK degradation by ClpCP decreases, because ComK is released (26). Thus, MecA, ClpC, and ComK, together with the signaling peptide ComS, form a regulatory mechanism controlling the activity of ComK.

Seki and Oshima examined DNA homology by DNA-DNA hybridization among Bacillus species and showed that the chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis natto strains is highly homologous to that of B. subtilis 168 (22). Moreover DNA extracted from natto strains can transform strain 168 as efficiently as DNA from strain 168. In fact, our preliminary transformation experiments showed that eight genetic markers at different positions on the chromosome of strain 168 could be efficiently transformed by DNA from the natto strain OK2, which was used in this study. Because of the industrial importance of the natto strain, we examined its ability to develop genetic competence and especially the expression of the late competence genes required for incorporation of exogenous DNA. In this paper, we present evidence that the natto strain has all the active late competence genes but that ComS in the natto strain is different from that in strain 168.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The B. subtilis natto strain OK2 was isolated from a commercial fermented soybean natto, “Okame natto,” produced by Takano Foods Co. in Ibaraki, Japan. This strain can ferment soybeans to make natto, carries two kinds of plasmids which have been recognized in many B. subtilis natto strains (25), and requires biotin for its growth. Spontaneous rifampin (rif21OK2)- or streptomycin (strA22OK2)-resistant mutants of strain OK2 were isolated by spreading on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 2 μg of rifampin/ml or 500 μg of streptomycin/ml. Both mecA and clpC (mecB) mutants derived from strain 168 were kindly provided by D. Dubnau. The construction of the strain carrying a translational comG-lacZ fusion at the amyE locus has been described previously (14).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis 168 and natto strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Marburg strains | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | |

| BD2123 | hisB2 leu-8 metB5 amyE::comG-lacZ mecA::spc | 14 |

| BD2243 | hisB2 leu-8 metB5 amyE::comG-lacZ clpC::spc | 14 |

| RIK1001 | trpC2 amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] | 17 |

| RIK1027 | trpC2 amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] pULI7KS27 | This work |

| RIK1023 | trpC2 rif1728 strA7 | 12; this work |

| Natto strains | ||

| OK2 | bio | This work |

| RIK7101 | bio amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] | This work |

| RIK7102 | bio amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] mecA::spc | This work |

| RIK7103 | bio amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] clpC::spc | This work |

| RIK7127 | bio amyE::[comG-lacZ (Cmr)] pULI7KS27 | This work |

| RIK7121 | bio rif21OK2 | This work |

| RIK7122 | bio strA22OK2 | This work |

Media and antibiotics.

The media used were LB (21), LB agar, and 2× SG medium (16). Media for preparation of competent cells consisted of Spizizen's minimal glucose (0.5% [wt/vol]) medium (1) supplemented with 0.05% and 0.025% yeast extract (Difco) for CI and CII (see below), respectively. For the B. subtilis natto strain, biotin was added at a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml. When present in selective media, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml; kanamycin, 7.5 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 50 μg/ml; and rifampin, 2 μg/ml.

Preparation of DNA.

Chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis was prepared as follows. Cells precultured at 28°C overnight were inoculated into LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics and were grown at 37°C with shaking until early-stationary phase. A 1.5-ml portion of the culture was centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 150 μl of SETL solution (20% sucrose, 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], and 2 mg of lysozyme/ml) containing 5 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml). After incubation at 37°C for 5 min, 600 μl of lysing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) was added and gently mixed. Thirty-five microliters of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) was added and mixed well, and then phenol-chloroform treatment was carried out three times. DNA was precipitated with an equal volume of 2-propanol and washed twice with 1 ml of 70% ethanol. DNA was dissolved in 200 μl of TE (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] and 1 mM EDTA) after drying in a vacuum desiccator.

Plasmid DNAs were prepared from cells grown until early-stationary phase in L broth at 37°C in the presence of appropriate antibiotics as described previously (2).

Preparation of competent cells and transformation.

Competent cells were prepared according to the two-step protocol as described previously (6). Cells were precultured on an LB plate at 28°C for about 16 h, inoculated into 5 ml of CI medium at an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of ca. 0.05, and grown at 37°C until early-stationary phase. A 0.5-ml portion of the culture was centrifuged, and the cell pellet was suspended in 1 ml of CII medium. An aliquot of 0.1 ml of the cell suspension was mixed with DNA and incubated at 37°C for 90 min with shaking. After the addition of 0.3 ml of LB medium to the culture, the culture was further incubated for 1 or 2 h, depending on the drug resistance markers used, and plated onto LB plates containing antibiotics suitable for selection.

Construction of plasmids.

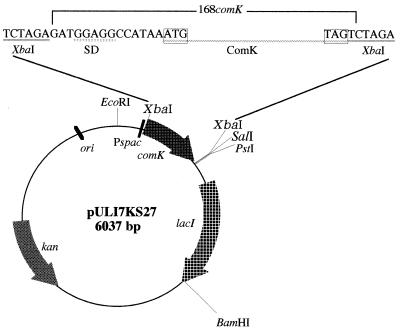

The 1.7-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pAG58 (13) containing the Pspac promoter and lacI gene was ligated with the 3.8-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pUB110 and transformed into B. subtilis 168 competent cells to construct pULI7. To construct the inducible comK expression plasmid pULI7KS27, the 601-bp comK-containing PCR fragment from B. subtilis 168 DNA was cloned into the XbaI site of pULI7. The PCR primers 5′-CAT CTC TAG AGA TGG AGG CCA TAA TAT GAG TCAG-3′ and 5′-TTA GTC TAG ACT AAT ACC GTT CCC CGA GCT CACG-3′, which have XbaI recognition sequences (underlined), were used for cloning the comK gene of B. subtilis 168 into pULI7 to produce pULI7KS27, as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Construction of pULI7KS27 carrying the Pspac-controlled comK gene. The 601-bp fragment containing the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) and coding sequences of the B. subtilis 168 comK gene was amplified by PCR and was inserted at the XbaI site of pULI7 as described in Materials and Methods.

Assay of β-galactosidase activity.

The β-galactosidase specific activity was determined as described previously (17). Strains were grown in CI or LB medium with or without isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; 0.1 to 1 mM), 200- to 500-μl samples were collected at the indicated times, and β-galactosidase activities were measured. One unit is equivalent to 1,000 × A420/OD660/ml/min, where A420 is the absorbance at 420 nm.

Other reagents and instruments.

Restriction enzymes, the PCR amplification kit, the DNA ligation kit, and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) were purchased from Takara Shuzo Co. (Shiga, Japan). For PCR, we used a model PJ2000 apparatus (Perkin-Elmer).

RESULTS

Transformation ability of the B. subtilis natto strain OK2.

We isolated the B. subtilis natto strain, designated OK2, from a commercial fermented soybean natto lot as described in Materials and Methods. To examine whether strain OK2 has transformation ability, we carried out transformation experiments with the chromosomal DNA prepared from RIK7121, a rifampin-resistant (rif21OK2) mutant of OK2. As shown in Table 2, strain OK2 gave only a few Rifr colonies per 0.1 ml. To examine whether these Rifr colonies were real transformants, strain OK2 was transformed with chromosomal DNA extracted from a rif1728 strA7 double mutant of strain 168, and the linkage between rif1728 and strA7 markers was determined. The cotransformation frequency of Rifr with Strr was found to be about 40%, indicating that these Rifr and Strr colonies were real transformants obtained via a homologous-recombination process (19). These results suggested that the homologous-recombination system in competent cells of strain OK2 functioned at a detectable level. Table 2 also shows that plasmid transformation with pUB110 DNA occurred at a frequency similar to that obtained with chromosomal DNA, indicating that strain OK2 cannot take up exogenous DNA. These results strongly suggested that a complete set of genes required for competence development does exist in strain OK2 but that they function inefficiently.

TABLE 2.

Transformation frequency in mecA and clpC mutants of the B. subtilis natto strain OK2

| Recipient | Genotype | Donor DNA

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifr mutant DNAa (no. of Rifr transformants/ml) | pUB110b (no. of Kmr transformants/ml) | ||

| B. subtilis 168 | trpC2 | 1.3 × 105 | 1.1 × 104 |

| B. subtilis OK2 | bio | 6.0 × 10 | 2.0 × 10 |

| RIK7101 | bio amyE::comG-lacZ | 2.0 × 10 | 1.5 × 10 |

| RIK7102 | bio amyE::comG-lacZ mecA::spc | 3.9 × 104 | 1.5 × 104 |

| RIK7103 | bio amyE::comG-lacZ clpC::spc | 2.1 × 104 | 1.1 × 103 |

DNA extracted from RIK7121 (bio rif21OK2) was used for transformation experiments at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. Cells were collected 4 h after inoculation. After the addition of LB medium, cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h with shaking and plated onto LB plates containing 2 μg of rifampin/ml.

pUB110 DNA extracted from strain 168(pUB110) was used for transformation experiments at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Cells were collected 4 h after inoculation. After the addition of LB medium, the cell culture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h with shaking and plated onto LB plates containing 7.5 μg of kanamycin/ml.

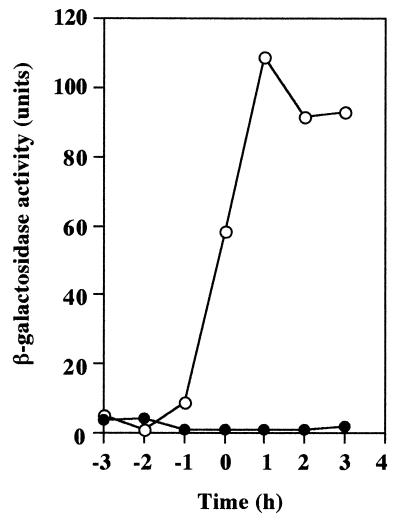

Extensive studies on competence development in B. subtilis Marburg 168 derivative strains have shown that the ComK protein can induce the transcription of all the late competence genes that are responsible for the uptake of exogenous DNA in macromolecular form (4, 8, 28–30). To examine whether an active ComK protein was produced, we first tried to introduce a translational comG-lacZ fusion at the amyE locus (14) of the OK2 chromosome. Two Cmr transformants of strain OK2 were obtained using the chromosomal DNA from strain 168 carrying a comG-lacZ fusion. To confirm whether these OK2 transformants contain the intact comG-lacZ fusion, strain 168 was transformed with their chromosomal DNAs and β-galactosidase activities in all Cmr transformants of strain 168 tested were induced during the development of competence (data not shown). The results in Fig. 2 show that comG-lacZ is not expressed. A possible explanation, based on our knowledge of B. subtilis 168, is that the level of ComK is greatly reduced in OK2.

FIG. 2.

Expression of comG-lacZ in B. subtilis 168 and the B. subtilis natto strain OK2. Cells were grown in CI medium, and samples (200 to 500 μl) were collected at the indicated times. β-Galactosidase activities were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Time zero is defined as the end of exponential growth. Symbols: ○, RIK1001 (168 amyE::comG-lacZ); ●, RIK7101 (OK2 amyE::comG-lacZ).

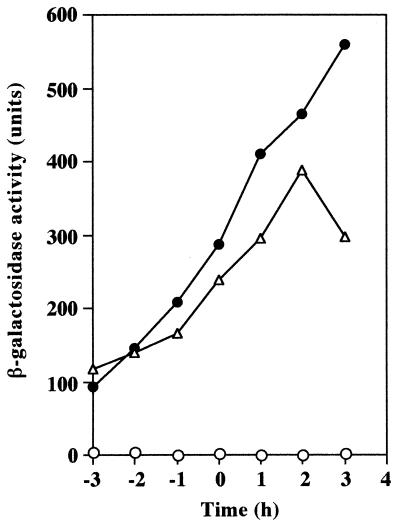

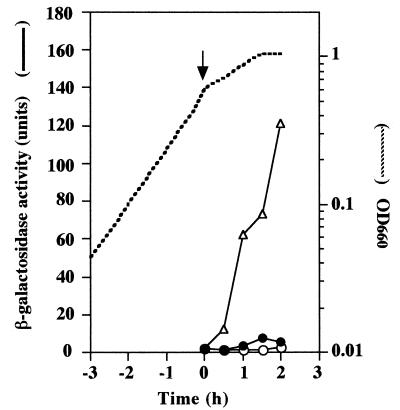

Expression of comG-lacZ in a mecA or clpC mutant of OK2.

It has been shown that the late competence genes, including the comG operon, are constitutively expressed even in rich media such as LB in either mecA or clpC (mecB) mutants (5). It has also been shown recently that these gene products in combination with ClpP protein inhibit the expression of the late competence genes by degrading ComK protein (26, 27). We therefore introduced a deletion of mecA or clpC into an OK2-derived strain carrying a comG-lacZ fusion and examined the transformation abilities and ComK activities of the mecA and clpC mutants by measuring comG-lacZ expression during competence development in CI medium (Table 2; Fig. 3). It seems plausible that an active ComK protein exists in strain OK2 and also that ComK produced in both mecA and clpC mutants of strain OK2 can activate the transcription of the comG operon as well as of the other late competence genes, since the transformation ability of strain OK2 was greatly enhanced by the introduction of either the mecA or the clpC mutation (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

The effect of mecA or clpC mutation on comG-lacZ expression in the B. subtilis natto strain OK2. Growth conditions and measurement of β-galactosidase activities were as specified in the legend to Fig. 2. Time zero is defined as the end of exponential growth. Symbols: ○, RIK7101 (OK2 amyE::comG-lacZ); ●, RIK7102 (OK2 amyE::comG-lacZ mecA::spc); ▵, RIK7103 (OK2 amyE::comG-lacZ clpC::spc).

Overproduction of ComK168 can develop genetic competence in strain OK2.

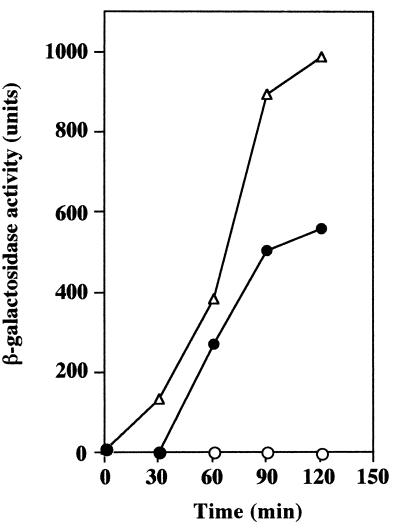

The results described above promptly led us to the idea that the transformation ability of OK2 would be enhanced by overproducing the ComK protein of strain 168 (ComK168). We therefore constructed plasmid pULI7KS27 (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1), containing a Pspac-controlled comK gene derived from 168, and examined the effect of overproduction of ComK168 on comG expression in strain 168 during the exponential-growth phase in LB medium. As shown in Fig. 4, the results indicate that plasmid pULI7KS27 produces sufficient ComK protein to induce the transcription of the late competence genes after the addition of 0.1 mM IPTG. During the construction of pULI7KS27, we found that 168 cells carrying this plasmid cannot form colonies on LB plates containing 1 mM IPTG, indicating that overproduction of ComK168 protein is toxic for the growth of 168.

FIG. 4.

Effect of comK induction on comG-lacZ expression in B. subtilis 168 during exponential growth. RIK1027 cells carrying pULI7KS27 (Fig. 1) were grown in LB medium containing 7.5 μg of kanamycin/ml. When the cell density reached an OD660 of 0.1, IPTG was added to the culture at various concentrations. Symbols: ○, 0 mM IPTG; ●, 0.1 mM IPTG; ▵, 1 mM IPTG.

We next introduced pULI7KS27 into OK2 carrying a translational comG-lacZ fusion to obtain RIK7127 and examined the effect of ComK168 overproduction on the late competence genes in OK2. The expression of comG-lacZ in RIK7127 was significantly induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG 3 h after the inoculation of RIK7127 cells into CI medium (Fig. 5). We also carried out the transformation experiment in which RIK7127 cells were collected 1 h after the addition of 1 mM IPTG, suspended in CII medium, and then mixed with RIK7121 (bio rif21OK2) DNA at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. We could obtain 2.4 × 103 Rifr transformants/ml. These results clearly showed that all of the late competence genes, as well as the homologous-recombination activity in OK2, could be induced by the overproduction of ComK168 protein.

FIG. 5.

Effect of comK induction on comG-lacZ expression in OK2 during competence development. RIK7127 cells carrying plasmid pULI7KS27 were grown in CI medium containing 7.5 μg of kanamycin/ml and 0.1 μg of biotin/ml as described in Materials and Methods. At the point shown by the arrow (T0, defined as the end of exponential growth), IPTG was added to the culture at the indicated concentrations, and β-galactosidase activities were measured as specified in the legend to Fig. 2. Symbols: ○, 0 mM IPTG; ●, 0.1 mM IPTG; ▵, 1 mM IPTG.

Difference in ComS between strains OK2 and 168.

The results described above, together with the information that ComS disrupts the ternary complex consisting of MecA, ClpC, and ComK (26, 27), clearly indicated that a complete set of late genes required for competence exists in OK2 and also suggested that ComS or ComK of strain OK2 may differ from that of 168. We first determined the nucleotide sequence of the comK gene of OK2 and could not find any difference in the predicted amino acid sequence of the ComK protein in spite of 11 differences in nucleotides between OK2 and 168. Furthermore, the AT-rich motif recognized by ComK (11) is conserved upstream of the comK promoter of OK2. We next determined the nucleotide sequences of the comS genes of OK2 and the other three natto strains, including strains Naruse, Takahashi, and Miyagino, which are widely used for natto fermentation in Japan, and found only a 1-base difference between the coding sequence of the comS gene of 168 and those of the natto strains. This single-base change resulted in the replacement of Ser (AGC) (strain 168) by Cys (TGC) (natto strains) at position 11 in the N terminus of ComS.

DISCUSSION

High transformation ability is observed in B. subtilis Marburg and its derivative strains but not in other B. subtilis strains. We isolated a B. subtilis natto strain, designated OK2, from a commercial natto preparation and examined whether it could develop genetic competence. We first carried out transformation experiments with OK2 using DNA extracted from a rif1728 strA7 (Rifr Strr) (12) double mutant of 168. Since the frequency of simultaneously spontaneous mutation in these two genes is expected to be about 10−8 × 10−8, or 10−16, it is difficult to obtain the spontaneous Strr Rifr double mutants. The frequency of cotransformation was 40%, and this value was in good agreement with those obtained in strain 168 (19, 23). We performed plasmid transformation experiments using pUB110, since plasmid transformation is known to be independent of RecA activity. The frequency of plasmid transformation was as low as that obtained with chromosomal marker transformation (Table 2). These results indicated that there was some defect in the function and/or expression of the late competence genes.

In B. subtilis 168, when ComK is activated, the transcription of all genes which are required for the uptake of external DNA is induced (8, 28–30). ComK activity can be easily monitored by measuring the expression of the comG operon using a translational comG-lacZ fusion (29). We therefore first introduced the translational comG-lacZ fusion (14) into OK2 and 168 and then measured β-galactosidase activity in CI medium. Although strong expression of comG was observed in strain 168 after the end of exponential growth, comG expression was not detected in OK2 throughout growth, suggesting that the absence of active ComK is the cause of the low transformation ability in OK2.

Based on these results, together with the fact that the late competence genes are constitutively expressed in 168 carrying a mecA or clpC mutation, we introduced a mecA or clpC mutation (14) into OK2 carrying the comG-lacZ translational fusion and examined the expression of the comG operon as well as transformability. We found that comG expression is strongly induced in both OK2 mutants during competence development (Fig. 3). Moreover, high transformation ability with Rifr chromosomal and pUB110 plasmid DNA was observed in these mutants (Table 2). It is thus likely that the comK gene of OK2 produces a functional ComK protein (ComKOK2) but that it is not fully activated during competence development in OK2 cells. To confirm this, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the comK gene in OK2 and examined the effect of ComK168 overproduction in OK2 cells. There was no difference between the deduced amino acid sequences of the ComK proteins of 168 and OK2, in spite of several differences in the nucleotide sequence. Furthermore, strain OK2 bearing pULI7KS27 showed strong expression of comG and high transformation ability when ComK168 was induced by the addition of IPTG (Fig. 5). These results again indicate that there is no difference in the ComK gene as well as the late competence genes between OK2 and 168.

Why cannot ComKOK2 in OK2 be activated? We assumed that ComKOK2 is not released from degradation by the MecA–ClpC–ClpP ternary complex in OK2. We therefore determined the nucleotide sequence of comS, whose product releases ComK from the ternary complex in 168 cells. We found only a 1-base change, resulting in a difference between the 11th amino acid of ComSOK2 (Cys [TGC]) and that of ComS168 (Ser [AGC]) (15). It has recently been shown that comG-lacZ expression was significantly reduced by the substitution of alanine for Ser11 of ComS168 (18). It has also been shown that ComS activity was greatly reduced by alanine substitution in the region between the 11th and 15th residues. In particular, the altered ComS with an alanine substitution at Ser13 completely lost its ability to bind to MecA (18). Furthermore, it was suggested that this N-terminal region containing Ser11 in ComS has an important role in binding to MecA (18). It is thus most likely that the alteration of ComS of strain OK2 affects its efficient interaction with MecA and that ComK is thereby constitutively degraded, resulting in the failure of expression of the late competence genes. Although it remains to be clarified whether the quorum-sensing signal transduction pathway in OK2 functions or not, the transformable B. subtilis natto strains are now available, as described in this paper. These transformable natto strains will be useful not only for genetic analysis but also for engineering improvements in natto strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. Dubnau for bacterial strains and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank R. H. Doi, P. Zuber, and M. M. Nakano for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Y. Chijiiwa for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan and by a grant, JSPS-RFTH96L00105, from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnboim H C. A rapid alkaline extraction method for the isolation of plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1983;100:243–255. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubnau D. Genetic exchange and homologous recombination. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 555–584. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubnau D. Binding and transport of transforming DNA by Bacillus subtilis: the role of type-IV pilin-like proteins—a review. Gene. 1997;192:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubnau D, Roggiani M. Growth medium-independent genetic competence mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4048–4055. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.4048-4055.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubnau D, Davidoff-Abelson R. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1971;56:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman A D. Genetic networks controlling the initiation of sporulation and the development of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:477–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn J, Kong L, Dubnau D. The regulation of competence transcription factor synthesis constitutes a critical control point in the regulation of competence in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5753–5761. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5753-5761.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn J, Luttinger A, Dubnau D. Regulatory inputs for the synthesis of ComK, the competence transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:763–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.371407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haijema B J, van Sinderen D, Winterling K, Kooistra J, Venema G, Hamoen L W. Regulated expression of the dinR and recA genes during competence development and SOS induction in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamoen L W, van Werkhoven A F, Bijlsma J J E, Dubnau D, Venema G. The competence transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis recognizes short A/T-rich sequences arranged in a unique, flexible pattern along the DNA helix. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1539–1550. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosoya Y, Okamoto S, Muramatsu H, Ochi K. Acquisition of certain streptomycin-resistant (str) mutations enhances antibiotic production in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2041–2047. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaacks K J, Healy J, Losick R, Grossman A D. Identification and characterization of genes controlled by the sporulation-regulatory gene spo0H in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4121–4129. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4121-4129.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong J H, Dubnau D. Regulation of competence-specific gene expression by Mec-mediated protein-protein interaction in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5793–5797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature (London) 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leighton T J, Doi R H. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3189–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanamiya H, Ohashi Y, Asai K, Moriya S, Ogasawara N, Fujita M, Sadaie Y, Kawamura F. ClpC regulates the fate of a sporulation initiation sigma factor, ςH protein, in Bacillus subtilis at elevated temperatures. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:505–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura M, Liu L, LaCelle M, Nakano M M, Zuber P. Mutational analysis of ComS: evidence for the interaction of ComS and MecA in the regulation of competence development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:799–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohashi Y, Sugimaru K, Nanamiya H, Sebata T, Asai K, Yoshikawa H, Kawamura F. Thermo-labile stability of ςH (Spo0H) in temperature-sensitive spo0H mutants of Bacillus subtilis can be suppressed by mutations in RNA polymerase β subunit. Gene. 1999;229:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Persuh M, Turgay K, Mandic-Mulec I, Dubnau D. The N- and C-terminal domains of MecA recognize different partners in the competence molecular switch. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:886–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seki T, Oshima Y. Taxonomic position of B. subtilis. In: Bunji M, Yoshikawa H, editors. Bacillus subtilis: molecular biology and industrial application. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; 1989. pp. 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith I. The translational apparatus of Bacillus subtilis. In: Dubnau D A, editor. The molecular biology of the bacilli. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1982. pp. 111–145. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon J M, Grossman A D. Who's competent and when: regulation of natural genetic competence in bacteria. Trends Genet. 1996;12:150–155. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka T, Koshikawa T. Isolation and characterization of four types of plasmids from Bacillus subtilis (natto) J Bacteriol. 1977;131:699–701. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.2.699-701.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turgay K, Hahn J, Burghoorn J, Dubnau D. Competence in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by regulated proteolysis of a transcription factor. EMBO J. 1998;17:6730–6738. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turgay K, Hamoen L W, Venema G, Dubnau D. Biochemical characterization of a molecular switch involving the heat shock protein ClpC controls the activity of ComK, the competence transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:119–128. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Sinderen D, Luttinger A, Kong L, Dubnau D, Venema G, Hamoen L. comK encodes the competence transcription factor (CTF), the key regulatory protein for competence development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:455–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Sinderen D, ten Berge A, Haijema B J, Hamoen L, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequence of comK, a gene required for genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Sinderen D, Venema G. comK acts as an autoregulatory control switch in the signal transduction route to competence in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5762–5770. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5762-5770.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]