Abstract

Within the context of residual cardiovascular risk in post-statin era, emerging evidence from epidemiologic and human genetic studies have demonstrated that triglyceride (TG)-rich lipoproteins and their remnants are causally related to cardiovascular risk. While, carriers of loss-of-function mutations of ApoC3 have low TG levels and are protected from cardiovascular disease (CVD). Of translational significance, siRNAs/antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting ApoC3 is beneficial for patients with atherosclerotic CVD. Therefore, animal models of atherosclerosis with both hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia are important for the discovery of novel therapeutic strategies targeting TG-lowering on top of traditional cholesterol-lowering. In this study, we constructed a novel mouse model of familial combined hyperlipidemia through inserting a human ApoC3 transgene (hApoC3-Tg) into C57BL/6 J mice and injecting a gain-of-function variant of adeno-associated virus-proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (AAV-PCSK9)-D377Y concurrently with high cholesterol diet (HCD) feeding for 16 weeks. In the last 10 weeks, hApoC3-Tg mice were orally treated with a combination of atorvastatin (10 mg·kg−1·d−1) and fenofibrate (100 mg·kg−1·d−1). HCD-treated hApoC3-Tg mice demonstrated elevated levels of serum TG, total cholesterol (TC) and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C). Oral administration of atorvastatin and fenofibrate significantly decreased the plaque sizes of en face aorta, aortic sinus and innominate artery accompanied by improved lipid profile and distribution. In summary, this novel mouse model is of considerable clinical relevance for evaluation of anti-atherosclerotic drugs by targeting both hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia.

Keywords: familial combined hyperlipidemia, ApoC3, mouse model, lipid-lowering, atherosclerosis

Introduction

Familial combined hyperlipidemia (FCHL) is a common and prevalent hereditary metabolic abnormality with complex inheritance, which is characterized by an increase in serum total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) levels [1, 2]. The increases in plasma lipids represent risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD-related mortality [3–5]. To date, the existing management strategies for FCHL patients are limited to therapeutic agents like statins to lower TC and TG levels [6]. The lack of suitable animal models of FCHL is an obstacle for mechanistic understanding of the genetic basis and pathophysiology of FCHL.

The Apolipoprotein C3 (ApoC3) gene cluster is closely linked with hyperlipidemia and plays a crucial role in the metabolism of TGs [7–9]. The correlation is positive such that the higher the level of ApoC3, the higher the incidence and severity of atherosclerosis in patients [10–12]. Volanesorsen, a novel antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting ApoC3 [13], effectively lowers TG levels in individuals with hyperlipidemia as found in the results of a phase 3 clinical trial [14]. In a mouse model, Li et al. [15] reported that ApoC3 transgene promoted the development of atherosclerotic aortic lesions in low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice after 3 months of feeding with an atherogenic diet. Other studies have shown that knockout of ApoC3 delays atherogenesis induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) in New Zealand White rabbits [16] and also led to attainment of an anti-atherogenic lipid profile in hamsters fed a high-cholesterol diet (HCD) [17]. ApoC3 has a strong correlation with hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis; however, the model described by Masucci-Magoulas et al. [18] requires the crossbreeding of human ApoC3 transgenic mice with LDLR-deficient mice (which is time- and cost-consuming). In this study, we aim to establish a novel mouse model of FCHL without crossbreeding with LDLR-deficient mice. We achieve this aim by inserting a human ApoC3 transgene (hApoC3-Tg) into C57BL/6 J (C57) mice and injecting a gain-of-function variant of adeno-associated virus-proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (AAV-PCSK9) [19]. This new model offers a novel research tool to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms and potential intervention strategies of FCHL.

Materials and methods

Animals

In our study, twenty 6-week-old male hApoC3-Tg mice (T055510) and five 6-week-old male C57 mice (N000013) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). After one week of adaptation, mice were divided into 4 groups according to body weight, 5 C57 mice and 5 hApoC3-Tg mice were fed a CD, 15 hApoC3-Tg mice were fed a HCD and injected AAV-PCSK9. After the corresponding 6-weeks of HCD, hApoC3-Tg mice were randomized to two groups. One group received oral gavage with atorvastatin (10 mg·kg−1·d−1) and fenofibrate (100 mg·kg−1·d−1) for 10 weeks. Another group received vehicle (40% PEG 300, 5% Tween 80 and phosphate buffer) administration. Atorvastatin (HY-B0589) and fenofibrate (HY-17356) were purchased from MedChemExpress Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Body weight of all mice was recorded once a week. All mice were sacrificed and tissues were harvested at week 16. H&E staining was performed to evaluate tissue injury. The animal ethics committee of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) approved the animal protocols (USTCACUC212401038).

Analysis of lipid metabolism

Blood was collected from fasted mice. Serum TC, TG, high density lipoprotein (HDL) and LDL levels were determined by a biochemical autoanalyzer, as same as serum levels of the liver enzyme alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST). Liver TG (FUJIFILM Wako, 290-63701) and TC (FUJIFILM Wako, 294-65801) were determined with commercial kits, respectively. Serum hApoC3 levels were measured using a hAPOC3 ELISA Kit (EHAPOC3, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

The assays of plasma (apo)lipoproteins

Fast-protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) of plasma lipoproteins was performed using 100 µL plasma samples from 5 animals with every groups to analyse lipid distribution, which were screened by 5 µm and applied to Tricorn high-performance Superose S-6 10/300GL columns (Amersham Biosciences), eluted with PBS at a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL/min [15]. TG and TC content in eluted fractions (500 µL per fraction) was assessed by using the same TG and cholesterol kits mentioned above.

Western blots

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) proteins in eluted fractions were determined using Western blots (WB). In short, every 3 consecutive fractions were pooled together and 15 µL of pooled fractions were mixed with 5 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer [15]. Samples were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. Proteins were separated by 4%–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for WB using different antibodies against ApoA1 (sc-30089, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA, rabbit polyclonal IgG, 1:2000) and ApoB (178467, Millipore, goat polyclonal IgG, 1:2000).

Quantification of atherosclerosis

Heart and en face aorta were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h and immersed in 30% sucrose overnight. The en face aorta was then cut longitudinally under a dissecting microscope and stained with a 60% Oil Red O (ORO) dye mixture (Poly Scientific R&D Corp., Cleveland, NY, USA). The top part of the heart and innominate artery were embedded in OCT and stored at −80 °C prior to sectioning [15]. Serial sections of aortic sinus (10 µm), where all three aortic valve cusps were clearly visible, were obtained and mounted consecutively on slides. Serial sections of innominate artery (8 µm) were also obtained on slides. Aortic sinus and innominate artery were cross-sectioned and stained with ORO to visualize lesion morphology [20]. The plaque sizes of en face aorta, aortic sinus and innominate artery were measured by using Image J software.

Metabolic assay

For the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), mice were fasted overnight. The glucose levels were measured using a glucose analyzer from VivaChek (Hangzhou, China) at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after oral gavage of glucose (2 g/kg) [21]. For the insulin tolerance test (ITT), insulin (0.75 U/kg) was administered via intraperitoneal injection. The glucose levels of the tail vein were measured at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after insulin administration [22].

Real-time PCR

The mRNA expression of mApoC3 and hAPOC3 in liver was quantified by real-time PCR. First, total RNA was isolated and purified from liver samples by using RNA isolation Kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Next the total RNA concentration was measured and reversed with a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan). Real-time PCR was performed by using a FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) [23, 24]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was set for internal reference. Primer sequences were listed as followed.

| hAPOC3-F | 5′-AGGAACAGAGGTGCCATGC-3′ |

| hAPOC3-R | 5′-CCTCTGAAGCTCGGGCAG-3′ |

| mApoc3-F | 5′-CCATCTAGCCCACAGAAGGC-3′ |

| mApoc3-R | 5′-CTACCTCTTCAGCTCGGGCA-3′ |

| mGapdh-F | 5’-AACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTC-3’ |

| mGapdh-R | 5’-CCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATT-3’ |

Statistics

Statistical analyses of the mouse data were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software). A 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare differences between 2 groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. The analysis of OGTT and ITT was based on the area under the curve (AUC), using two tailed of unpaired t-test. Body weight analysis involved two-way ANOVA to compare the weights of two groups with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

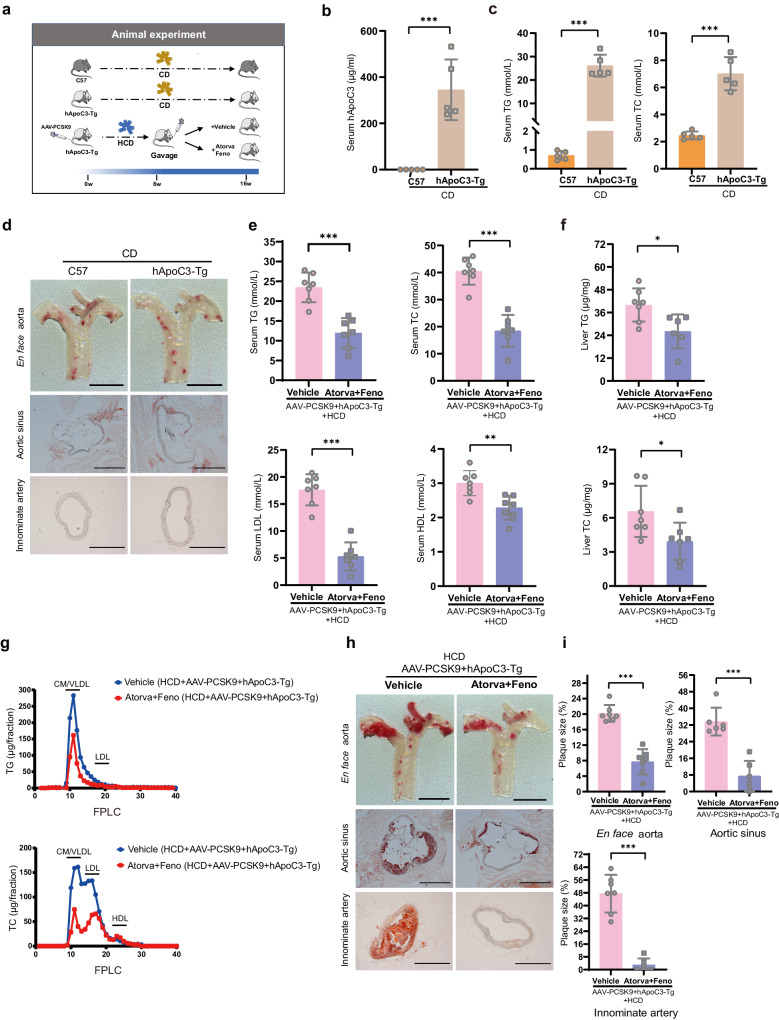

In this study, we first evaluated hyperlipidemic phenotypes in hApoC3-Tg mice fed a chow diet (CD) using C57 mice as the control group. Then, hApoC3-Tg mice were injected with AAV-PCSK9 and fed a HCD for a total of 16 weeks. The hApoC3-Tg mice were divided into two groups at week 6, and the mice were treated with either vehicle or a combination of atorvastatin (10 mg·kg−1·d−1) and fenofibrate (100 mg·kg−1·d−1) orally for 10 weeks (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. A new mouse model of familial combined hyperlipidemia (FCHL) and atherosclerosis suitable for the evaluation of potential pharmaceutical agents.

a Animal experiment flow chart. b Serum hApoC3 level in hApoC3-Tg mice and C57 mice fed a CD (n = 5). c Serum TG and TC level in hApoC3-Tg mice and C57 mice fed a CD (n = 5). d Representative micrographs of Oil Red O (ORO) staining of en face aorta (scale bar = 3.5 mm, top panel), aortic sinus (scale bar = 100 µm, middle panel) and innominate artery (scale bar=100 µm, bottom panel) in hApoC3-Tg mice and C57 mice fed a CD. e Serum TG, TC, LDL and HDL levels between vehicle and combination group (Atorvastatin/Fenofibrate) (n = 7). f Liver TG (n = 6–7) and TC (n = 7) levels between combination treatment group and vehicle control group. g Fractions of CM, VLDL, LDL and HDL in lipoprotein profiles through FPLC (n = 5). h Representative micrographs of ORO staining of en face aorta (scale bar=3.5 mm), aortic sinus (scale bar = 100 µm) and innominate artery (scale bar = 100 µm) from top to bottom between vehicle and combination group (Atorvastatin/Fenofibrate). i Statistical analysis of plaque size in en face aorta (n = 7), aortic sinus (n = 6) and innominate artery (n = 6–7) between combination treatment group and vehicle control group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. A 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare differences between 2 groups. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We collected serum from all mice at the end of experiments. Firstly, we verified the expression of hApoC3 protein and mRNA in liver tissues of hApoC3-Tg mice fed a CD compared with control mice (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S1a). hApoC3-Tg mice showed elevated levels of serum TG, TC, LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), ALT and AST levels compared with wild type (WT) control mice fed a CD (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S1b, c). The plasma lipoprotein profiles between groups were analyzed using FPLC. As expected, hApoC3-Tg mice exhibited an increase in the fractions of chylomicron (CM), very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and LDL compared with control mice (Supplementary Fig. S1d). However, there was no change in the number of leukocytes and erythrocytes, as same as the proportion of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes (Supplementary Fig. S1e). An increase in serum apolipoprotein B48 (ApoB48) and apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100) was observed by WB in hApoC3-Tg mice (Supplementary Fig. S1f). To investigate whether or not this atherogenic lipid profile could promote atherosclerosis development, we stained en face aorta, aortic sinus and innominate artery with ORO and found that there was no visible lipid deposition in either group of mice (Fig. 1d). Collectively, our data demonstrated that a hyperlipidemic phenotype was successfully established by hApoC3 transgene. However, no visible lesion formation was observed despite overt hypertriglyceridemia.

To induce atherosclerotic plaque formation, we injected AAV8-PCSK9-D377Y [19] into control or hApoC3 transgenic mice concurrently with HCD feeding. We found serum TC and LDL-C levels were further increased. Elevation of circulating levels of TG, TC, LDL and HDL were reversed after treatment with atorvastatin and fenofibrate (Fig. 1e). Additionally, this combination therapy could lower liver TG and TC content significantly (Fig. 1f), but serum AST level had a significant increase after combination treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Not only the concentration of TG and TC carried on CM, VLDL and LDL particles was reduced (Fig. 1g), but also serum ApoB48 and ApoB100 levels were markedly lower after combination therapy (Supplementary Fig. S2b). In line with the findings showing that the atherogenic lipid profiles were reversed after combination treatment, the plaque lesion size of en face aorta, aortic sinus and innominate artery was apparently reduced (Fig. 1h, i). Consistent with the results reported by Kanter et al. [25], we also found that there were no changes in the number of leukocytes and erythrocytes, and the proportion of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes also showed no differences between vehicle control group and combination treatment group (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Additionally, there were no differences in body weight at week 16, nor OGTT results at week 11 or ITT results at week 13 either under conditions of CD (Supplementary Fig. S1g–i) or HCD (Supplementary Fig. S2d–f) feeding.

We note that the combination administration led to an increase of serum AST level, although this treatment reduced atherosclerotic plaque markedly. Clinical studies have also shown that fenofibrate-statin combination therapy leads to significantly higher incidence of elevated aminotransferase than the statin monotherapy group [26–28]. However, there was no change in level of enzymes indicative of kidney and heart functions after treatment with atorvastatin and fenofibrate; kidney morphology showed no significant change and improved hepatic steatosis observed after combination therapy (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b). Thus, this result indicates the potential use of this combination regimen in patients with FCHL whilst monitoring of liver function to avoid hepatic toxicity, so as to achieve the goal of safe and effective lowering of blood lipids and reduced atherosclerotic plaque burden.

In conclusion, we have established a novel mouse model of familial combined hyperlipidemia without crossbreeding with LDLR deficient mice. This new mouse model is of clinical relevance for patients with elevated risk of atherosclerosis, providing an ideal tool to evaluate anti-atherosclerotic drugs targeting both high TG and TC levels as compared to traditional mouse models of atherosclerosis (including ApoE deficient mice, LDLR deficient mice or AAV-PCSK9 injected mice) [29].

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFC2500500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82370444, 82070464, 82003741, 82270479, 82070460) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB38010100). This work was also supported by the Program for Innovative Research Team of The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC (CXGG02), Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 202104j07020051), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2208085J08). Suo-wen Xu is the recipient of Humboldt Fellowship for Experienced Researchers from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Mei-jie Chen, Yi-tong Xu

Contributor Information

Xun-de Xian, Email: xianxunde@bjmu.edu.cn.

Jian-ping Weng, Email: wengjp@ustc.edu.cn.

Suo-wen Xu, Email: sxu1984@ustc.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-024-01241-8.

References

- 1.Goldstein JL, Schrott HG, Hazzard WR, Bierman EL, Motulsky AG. Hyperlipidemia in coronary heart disease. II. Genetic analysis of lipid levels in 176 families and delineation of a new inherited disorder, combined hyperlipidemia. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1544–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI107332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill PK, Hegele RA. Familial combined hyperlipidemia is a polygenic trait. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2022;33:126–32. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luijten J, Greevenbroek MMJ, Schaper NC, Meex SJR, Steen C, Meijer LJ, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in familial combined hyperlipidemia: A 15-year follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 2019;280:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin MA, McKnight B, Edwards KL, Bradley CM, McNeely MJ, Psaty BM, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in familial forms of hypertriglyceridemia: A 20-year prospective study. Circulation. 2000;101:2777–82. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.24.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Q, Huang Y, Kong X, Jia B, Lu X, Chen Y, et al. QDBLiPro: a database for lipids and proteins in human lipid metabolism. Phenomics. 2023;3:350–9. doi: 10.1007/s43657-023-00099-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braamskamp MJAM, Wijburg FA, Wiegman A. Drug therapy of hypercholesterolaemia in children and adolescents. Drugs. 2012;72:759–72. doi: 10.2165/11632810-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packard CJ, Pirillo A, Tsimikas S, Ferenve BA, Catapano AL. Exploring apolipoprotein C-III: pathophysiological and pharmacological relevance. Cardiovasc Res. 2024;119:2843–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Taskinen M-R, Borén J. Why is apolipoprotein CIII emerging as a novel therapeutic target to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:59. doi: 10.1007/s11883-016-0614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saleheen D, Natarajan P, Armean IM, Zhao W, Rasheed A, Khetarpal SA, et al. Human knockouts and phenotypic analysis in a cohort with a high rate of consanguinity. Nature. 2017;544:235–9. doi: 10.1038/nature22034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks FM, Alaupovic P, Moye LA, Cole TG, Sussex B, Stampfer MJ, et al. VLDL, apolipoproteins B, CIII, and E, and risk of recurrent coronary events in the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) trial. Circulation. 2000;102:1886–92. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.16.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng C. Updates on apolipoprotein CIII: fulfilling promise as a therapeutic target for hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2014;25:35–39. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luc G, Fievet C, Arveiler D, Evans AE, Bard JM, Cambie F, et al. Apolipoproteins C-III and E in apoB- and non-apoB-containing lipoproteins in two populations at contrasting risk for myocardial infarction: the ECTIM study. Etude Cas Témoins sur ‘Infarctus du Myocarde. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:508–17. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)37594-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaudet D, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Alexander VJ, Singleton W, Hughes SG, et al. Targeting APOC3 in the familial chylomicronemia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2200–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witztum JL, Gaudet D, Freedman SD, Alexander VJ, Digenio A, Williams KR, et al. Volanesorsen and triglyceride levels in familial chylomicronemia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:531–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Han Y, Qi R, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yu M, et al. Aggravated restenosis and atherogenesis in ApoCIII transgenic mice but lack of protection in ApoCIII knockouts: the effect of authentic triglyceride-rich lipoproteins with and without ApoCIII. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:579–89. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zha Y, Lu Y, Zhang T, Yan K, Zhuang W, Liang J, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of APOC3 stabilizes plasma lipids and inhibits atherosclerosis in rabbits. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20:180. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01605-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo M, Xu Y, Dong Z, Zhou Z, Cong N, Gao M, et al. Inactivation of ApoC3 by CRISPR/Cas9 protects against atherosclerosis in hamsters. Circ Res. 2020;127:1456–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masucci-Magoulas L, Goldberg IJ, Bisgaier CL, Serajuddin H, Francone OL, Breslow JL, et al. A mouse model with features of familial combined hyperlipidemia. Science. 1997;275:391–4. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjørklund MM, et al. Induction of atherosclerosis in mice and hamsters without germline genetic engineering. Circ Res. 2014;114:1684–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centa M, Ketelhuth DFJ, Malin S, Gistera A. Quantification of atherosclerosis in mice. J Vis Exp. 2019; 10.3791/59828. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hu W, Li M, Sun W, Li Q, Xi H, Qiu Y, et al. Hirsutine ameliorates hepatic and cardiac insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced diabetic mice and in vitro models. Pharmacol Res. 2022;177:105917. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagy C, Einwallner E. Study of in vivo glucose metabolism in high-fat diet-fed mice using oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT). J Vis Exp. 2018;56672. 10.3791/56672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Xu S, Liu Y, Ding Y, Luo S, Zheng X, Wu X, et al. The zinc finger transcription factor, KLF2, protects against COVID-19-associated endothelial dysfunction. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:266. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00690-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S, Wu X, Wang S, Xu M, Fang T, Ma X, et al. TRIM56 protects against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via promoting the degradation of fatty acid synthase. J Clin Invest. 2024;134:e166149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kanter JE, Shao B, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Shimizu-Albergine M, Vaisar T, et al. Increased apolipoprotein C3 drives cardiovascular risk in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4165–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI127308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo J, Meng F, Ma N, Li C, Ding Z, Wang H, et al. Meta-analysis of safety of the coadministration of statin with fenofibrate in patients with combined hyperlipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng Q, Ren J, Li S, Chen H. A meta-analysis on the safety of combination 27 therapy with fenofibrate and statins. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2013;41:1063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geng Q, Ren J, Chen H, Lee C, Liang W. Adverse events following statin-fenofibrate therapy versus statin alone: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:219–26. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ilyas I, Little PJ, Liu Z, Xu Y, Kamato D, Berk BC, et al. Mouse models of atherosclerosis in translational research. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022;43:920–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.