Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) regulate pain pathways with various outcomes depending on receptor subtypes, neuron types, and locations. But it remains unknown whether α4β2 nAChRs abundantly expressed in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) have potential to mitigate hyperalgesia in pain states. We observed that injection of nAChR antagonists into the SNr reduced pain thresholds in naïve mice, whereas injection of nAChR agonists into the SNr relieved hyperalgesia in mice, subjected to capsaicin injection into the lower hind leg, spinal nerve injury, chronic constriction injury, or chronic nicotine exposure. The analgesic effects of nAChR agonists were mimicked by optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic inputs from the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) to the SNr, but attenuated upon downregulation of α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons and injection of dihydro-β-erythroidine into the SNr. Chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia depended on α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons and was associated with the reduction of ACh release in the SNr. Either activation of α4 nAChRs in the SNr or optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr cholinergic projection mitigated chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia. Interestingly, mechanical stimulation-induced ACh release was significantly attenuated in mice subjected to either capsaicin injection into the lower hind leg or SNI. These results suggest that α4 nAChRs on GABAergic neurons mediate a cholinergic analgesic circuit in the SNr, and these receptors may be effective therapeutic targets to relieve hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain, and chronic nicotine exposure.

Keywords: pain, cholinergic system, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, substantia nigra pars reticulata, pedunculopontine nucleus, chronic nicotine

Introduction

As a major complain in many diseases, pain is an important manifestation to treat in patients of these diseases. Currently, opioids are still among the few accountable drugs conferring efficient analgesic effect [1–3]. But because of the devastating side-effects of the opioids [4–6], non-opioid drugs have been sought to develop better pain therapies. Accumulating evidence hints that cholinergic system in the central nervous system may be a promising target for mitigating inflammatory pain, migraine, and neuropathic pain [7–12]. However, varying effects on nociception of cholinergic agents prompt further investigations to address analgesic effects of cholinergic receptors in distinct nuclei.

The most abundant nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the central nervous system contain α4β2 subunits (referred as α4β2 nAChRs) [13–18]. Molecular pharmacological and mouse genetic studies convincingly reveal that α4 and β2 subunits rely on each other to form functional nAChRs [14, 19–24]. Therefore, detection of either α4 or β2 subunit may reveal the distribution of α4β2 nAChRs. Ligand-binding assay, mouse lines with mutant gain-of-function α4 subunit, and mouse lines with fluorescence-tagged α4 subunit show that α4β2 nAChRs are densely expressed in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra [13–18, 23–25]. Numerous studies implicate VTA α4β2 nAChRs in nicotine addiction [14, 17, 21, 26, 27]. However, the roles of α4β2* nAChRs in the substantia nigra have been understudied. GABAergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) play a critical role in pain modulation; stimulation of these neurons and their projections to the subthalamic nucleus relieves acute and chronic pain [28, 29]. As α4β2 nAChRs are well-documented to excite SNr GABAergic neurons [18, 22], α4β2 nAChRs on the SNr GABAergic neurons may mediate analgesic effects of nAChR agonists.

Cigarette smoking is a serious public health problem in the world [30]. It causes the greatest number of preventable death and chronic diseases, and poses a tremendous social economic burden to the society. Smoking cessation has been proven to dramatically reduce the prevalence of many types of tumors and cancers [30, 31]. But it is difficult for smokers to quit smoking because nicotine, one of bioactive components in cigarette, activates nAChRs, leading to addiction, and abstinence of smoking often incurs striking somatic and emotional withdrawal symptoms, including hyperalgesia [17, 30–36]. It is noteworthy that chronic nicotine exposure upregulates both number and function of α4β2 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons [18, 22]. Further investigations are needed to address whether modifications by chronic nicotine may transit the function of α4β2 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons from analgesia to hyperalgesia.

In the present study, we utilized neuropharmacological, optogenetic, and viral vector-assisted molecular techniques to modulate cholinergic inputs to SNr neurons and demonstrated that activation of α4 nAChRs in SNr neurons relieved hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain states and after chronic nicotine exposure. Using a genetically encoded fluorescent acetylcholine (ACh) sensor, we found that chronic nicotine reduced pain stimulation-evoked ACh release in the SNr. Our results suggest that cholinergic circuit in the SNr composed of α4 nAChRs on GABAergic neurons and cholinergic inputs from the pedunculopontine nucleus plays an important role in the maintenance of pain thresholds. This circuit confers analgesia in pain states when it is enhanced, but causes hyperalgesia after it is modified by repetitive nicotine exposure. Therefore, enhancement of the SNr cholinergic circuit may be a potential therapeutic intervention strategy for pain relief.

Materials and methods

Animals

The care and use of animals and the experimental protocols used in this study comply with the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (1988) in China and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Office of Laboratory Animal Resources of Xuzhou Medical University. C57BL/6 J background ChAT-Cre (stock no. 006410) and Vgat-IRES-Cre (stock no. 028862) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Heterozygous transgenic mice were crossed with wild type C57 BL/6 J mice for breeding in the animal facility of Xuzhou Medical University. The male transgenic and C57 BL/6 J wild type mice (>8 weeks old) used for experiments were group housed (no more than 5 per cage) on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to water and food. All behavioral experiments were performed in the light cycle. Efforts were made to minimize mouse suffering and to reduce the number of mice used.

Viral vectors

The following viral vectors [adenovirus-associated virus (AAV), serotype 2, 1 × 1012 to 5 × 1012 vg/ml]: AAV-CMV-DIO-(EGFP-U6)-shRNA(Chrna4)-WPRE-hGH polyA, AAV-CMV-DIO-(eGFP-U6)-shRNA(scramble)-WPRE-hGH polyA, AAV-CMV-DIO-Chrna4-P2A-eGFP-WPREs, AAV-CMV-DIO-eGFP-WPRE-hGH, AAV-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP, AAV-EF1α-DIO-eYFP, AAV-hSyn-eGFP and AAV retro-hSyn-mCherry were constructed and provided by Brain VTA (Wuhan, China); AAV-hSyn-GACh3.0 was purchased from Vigene Biosciences (Jinan, China).

Mouse surgeries

Male mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5% for induction, 1.5% for maintenance) and stabilized in a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China) and on a heating pad. The surgery was performed as described previously [28, 37].

For pharmacological manipulation, a stainless steel guide cannula (26 G, RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China) was implanted 500 μm above the SNr (AP, −3.1 mm; ML, 1.5 mm; DV, 4.2 mm) as the injection needle for drug delivery is 500 μm longer than the cannula. After 7 days recovery, the mice were lightly anesthetized with 1% isoflurane, and agonists and antagonists of nAChRs (300 nl) were injected into the SNr with a microinjection pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, USA) at a rate of 50 nl/min. Pain-like behaviors were performed 15 min after the mice recovered from anesthesia.

For optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic innervation from the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) to the SNr, we injected AAV2/9-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP or AAV2/9-EF1α-DIO-eYFP into the PPN (AP, −4.5 mm; ML, 1.3 mm; DV, 4.2 mm) [38] and implanted optical fiber [200 μm in diameter, NA 0.37 (Inper, Hangzhou, China)] into the SNr (AP, −3.1 mm; ML, 1.5 mm; DV, 4.5 mm). The mice were allowed to recover for at least 3 weeks before the behavioral test, optogenetic manipulation, and morphological assay.

For cell-specific down- and up-regulation of α4 nAChRs, AAV-CMV-DIO-(EGFP-U6)-shRNA(Chrna4)-WPRE-hGH polyA (for downregulation) (shRNA)/ AAV-CMV-DIO-(eGFP-U6)-shRNA(scramble)-WPRE-hGH polyA (for control) (scrRNA) or AAV-CMV-DIO-Chrna4-P2A-eGFP-WPREs (for upregulation) (Chrna4) / AAV-CMV-DIO-eGFP-WPRE-hGH (for control) (eGFP) was injected into the SNr of Vgat-Cre mice. The outcome was confirmed with q-RT-PCR and brain slice patch-clamp technique.

For postoperative pain relief, meloxicam (4 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected once per day for 3 days. The expression of viral vectors and the position of the cannula implants or optical fibers in mice were confirmed histologically after the experiments.

Optogenetic manipulation

For photostimulation, 473-nm laser pulses (5 ms, 20 Hz, 4 mW) were delivered into the SNr from a laser generator (Newdoon, Hangzhou, China or Inper, Hangzhou, China). All optogenetic manipulations were performed unilaterally on the right hemisphere.

Fiber photometry

Mice was placed on a wide gauge mashed net lifted on a stand. Fiber photometry instrument (ThinkerTech, Nanjing, China) [39, 40] was used to monitor GACh and eYFP signals in the SNr when the mice received mechanical pressure on the tail or hind paw. We analyzed GACh signal 3 s before stimulation and calculated mean (F0) and its standard deviation (SD), then transformed GACh signal (F) in the full trial into z-scores [(F - F0)/SD]. The peak z-score of GACh signal during pain-like response was calculated.

von Frey filament test

The von Frey filaments were used to measure the mechanical thresholds of both hind paws of acclimatized mice in a test compartment on a wide gauge wire mesh supported by an elevated platform as described previously [28, 37, 41, 42]. The fiber forces of von Frey filaments range from 0.008 g to 4 g. The 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was calculated using Dixon’s up–down method [43].

Thermal nociception threshold

Thermal paw withdrawal latencies (PWL) in both hind paws were recorded with a plantar anesthesia tester (Boerni, Tianjin, China) in acclimatized mice in a test compartment on a glass surface [28, 37]. A heating light source was positioned over the plantar surface of the hind paw and the withdrawal latency was measured. A 20 s cut-off time was used to prevent potential tissue damage to the surface of the hind paw.

Capsaicin-induced secondary mechanical hyperalgesia

Capsaicin (0.01%, 20 µL in 10% DMSO/saline) was injected subcutaneously in the lower hind leg to induce secondary mechanical hyperalgesia in the plantar area of the hind paw [44].

Spared nerve injury

Spared nerve injury (SNI) was used to establish a neuropathic pain model, according to previous reports [28, 29, 45]. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, a longitudinal incision was made from the knee to the hip and a blunt dissection was performed to expose the sciatic nerve and its branches (sural, common peroneal, and tibial nerves). The common peroneal and tibial nerves were tightly ligated with two nylon sutures 3−4 mm apart and a 2 mm section in each nerve between the sutures was removed, but the sural nerve was kept intact. Some mice were subjected to skin incision and dissociation of sciatic nerve without nerve ligation and severing. These mice were used as sham controls. For pain threshold measurements, the von Frey filaments and heating beam were targeted to the skin area innervated by the sural nerve.

Chronic constriction injury

Chronic constriction injury (CCI) was used to establish a neuropathic pain model, according to previous reports [46, 47]. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, a longitudinal incision was made from the knee to the hip and a blunt dissection was performed to expose the sciatic nerve. Three nerve ligations separated by 1 mm were made on the sciatic nerve. Some mice were subjected to skin incision and dissociation of sciatic nerve without nerve ligation. These mice were used as sham controls. For pain threshold measurements, the von Frey filaments and heating beam were targeted to the skin area in the hind paw.

Chronic nicotine treatment

Nicotine (0.5 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected once per day in the morning for consecutive 14 days.

Locomotion

Each mouse was placed in the center of a cylinder (30 cm in diameter, 40 cm in height) and allowed to roam freely for 20 min. The locomotor activity of these mice was recorded and analyzed with the EthoVision XT 14.0 software.

Histology

Mice were sacrificed in a CO2 chamber and then subjected to cardiac perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Mouse brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. For immunostaining [37, 48], brain sections were incubated in a blocking buffer containing 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 90 min at room temperature. Then the sections were incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 24 h at 4 °C (rabbit anti-c-Fos IgG, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology; goat anti-ChAT IgG, 1:100, Millipore; Chicken anti-TH IgG, 1:500, Aves Lab; Rabbit anti-GABA IgG, 1:200, Millipore). After washing three times (10 min each) in PBS, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa 488- / Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, 1:500; Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgG, 1:500; Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG, 1:500; all from Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 90 min at room temperature. The sections were washed three times (10 min each) in PBS, dried in the dark, and then cover-slipped in mounting medium (Meilunbio, Dalian, China).

The sections were imaged with a confocal microscope (LSM 880, Zeiss, Wetzlar, Germany) and the images were processed with ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA extraction

Mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber and decapitated with a guillotine. The brains were removed, washed with ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), placed in a mouse brain module with coronal slots on both sides every 0.5 mm, and cut into 1 mm thick sections. The substantia nigra was dissected from the section, placed and sealed in a nuclease-free tube, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA extraction was conducted according to manufacturer’s manual (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan). The RNA was solved in 30 μl nuclease-free water and stored at −80 °C.

In some experiments, eGFP-labeled SNr neurons and mCherry-labeled SNc neurons were separately collected into lysis buffer filled in the cap of a 200 μl nuclease-free Eppendorf tube using a laser capture apparatus (30 neurons/tube) (Fig. S2d, S2e, S3d, S3e) (Zeiss, Wetzlar, Germany), and the tubes were stored at −80 °C for further assays.

cDNA synthesis

RNA samples were reversely transcribed into cDNA in a reaction system recommended in the manual of TaKaRa PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). Briefly, the RNA sample was mixed with PrimeScript RT Master Mix and RNase-free water, incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, then, at 85 °C for 5 s. The cDNA product was kept at 4 °C or −20 °C.

Real-time PCR

cDNA samples were mixed with SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Low ROX), primers (Table 1), and ddH2O was added to reach a volume of 20 μl in a 200 μl Eppendorf tube. The tubes were put in an ABI QuatStudio7 Flex (LifeTechnologies, Carlsbad, CA), and the samples were amplified using an optimized protocol. For PCR, the mixtures were heated sequentially at 95 °C for 15 s, at 60 °C for 20 s, and then at 72 °C for 30 s. The protocol was repeated for 40 cycles. A melt curve was obtained by heating the sample at 95 °C for 15 s, at 60 °C for 60 s, and then at 95 °C for 15 s. Each sample was amplified in two duplicated tubes. The mRNA level of a particular gene was normalized to that of Gapdh (folds of Gapdh) according to the manual provided by the manufacturer.

Table. 1.

Primer sequence for genes measured in qPCR analysis.

| gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| α4 | TGCGCTGGGACCCTGGTGACTAC | TCCCCGTCCGCGTTGTTGTAGAG |

| β2 | TGCGAAGTGAAGATGATGACCAG | ACATGCCAATGGTCCCAAAGA |

| α7 | TGCCACATTCCACACCAACG | CTACGGCGCATGGTTACTGT |

| Th | GTGGAGACAGAACTCGGGAC | TCCAATGAACCTTGGGGACG |

| Vgat | CACGACAAACCCAAGATCACG | AGCACGAACATGCCCTGAA |

| Gapdh | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

Chemicals

Capsaicin, dihydro-β-erythroidine hydrobromide, galantamine hydrobromide, mecamylamine hydrochloride, and Rivanicline (RJR-2403) hemioxalate were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Nicotine bi-L(+)-tartrate dihydrate was purchased from Aladdin Scientific (Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

For pharmacological, optogenetic, and behavioral experiments, mice were randomly assigned to saline/control/sham and experimental groups. For pain behavior assessments, the experimenters were blind to the chemicals and viral vectors injected into the mice. For electrophysiological recordings of nAChR-mediated currents, patch-clamp performer was blind to the types of viral vector injected into the SNr. GraphPad Prism (version 7.0) was used for all statistical analyses. All summarized data are presented as mean ± SEM and scatter points in histograms. Two-tailed paired or unpaired t-tests, one-way ANOVAs followed by post-hoc Bonferroni tests, or two-way ANOVAs were used to compare behavioral and histological data, as indicated in the figure legends. If the data did not pass either normal distribution or equal-variance tests, statistical significance of the data was evaluated with the Mann–Whitney test or two–way or one–way ANOVA rank tests. Statistics of the data are included in Table S1 in supplementary materials. In all tests, values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhibition of nAChRs in the SNr reduces pain threshold

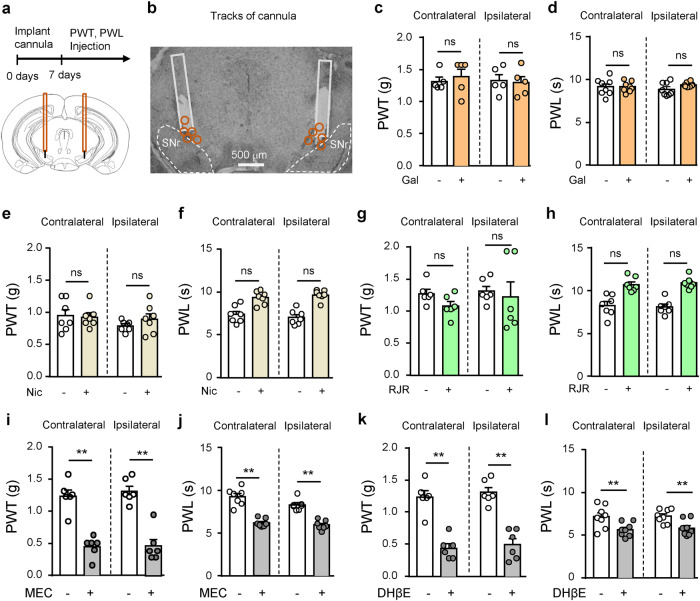

To address whether nAChRs in the SNr modulate pain threshold, we implanted cannula above the SNr for injection of galantamine, an inhibitor for acetylcholinesterase, nAChR agonists, and nAChR antagonists into the SNr, and measured mechanical and thermal thresholds before and after drug injection (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1. Inhibition of nAChRs in the SNr reduces pain threshold in mice.

a, b Diagram and a representative image showing injection of drugs into the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) through cannulas. Orange circles represent locations of cannulas. c, d Mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) and thermal paw withdrawal latency (PWL) on both hind paws after saline (-) (n = 7) or galatamine (+) (Gal, 10 μM, 300 nl) (n = 7) injection into the SNr. e, f PWT and PWL on both hind paws after saline (-) (n = 7) or nicotine (+) (Nic, 1 μM, 300 nl) (n = 7) injection into the SNr. g, h PWT and PWL on both hind paws after saline (-) (n = 7) or RJR-2403 (+) (RJR, 500 μM, 300 nl) (n = 7) injection into the SNr. i, j PWT and PWL on both hind paws after saline (-) (n = 7) or mecamylamine (+) (MEC, 100 μM, 300 nl) (n = 7) injection into the SNr. k, l PWT and PWL on both hind paws after saline (-) (n = 7) or DHβE (+) (0.3 μM, 300 nl) (n = 7) injection into the SNr. Two-tailed paired t-tests were used for (c−l). n = 7. ‘ns’ not significant. **P < 0.01.

When we injected galantamine (10 μM, 300 nl) into the SNr to cause accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh), we did not observe alterations in either mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) or thermal paw withdrawal latency (PWL) (Fig. 1c, d). As ACh activates both muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) and nAChRs whose effects on pain threshold may counteract with each other [7, 8, 17], we turned to inject nicotine into the SNr. Again we did not find significant changes in either mechanical or thermal threshold (Fig. 1e, f). We then injected α4β2 nAChR agonist, RJR-2403 (500 μM, 300 nl), into the SNr and observed no change in either mechanical or thermal threshold in mice (Fig. 1g, h). These results support that stimulating SNr neurons by activating nAChRs may not change pain thresholds in the physiological condition. It is consistent with our previous study showing that optogenetic stimulation of SNr GABAergic neurons does not affect either mechanical or thermal threshold in naïve mice [28].

We next examined the effects of nAChR antagonists in the SNr on mechanical and thermal thresholds. We found that injection of either mecamylamine (MEC) (100 μM, 300 nl), a broad spectrum nAChR antagonist, or dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) (0.3 μM, 300 nl), an α4β2 nAChR selective antagonist, into the SNr reduced both mechanical and thermal thresholds on both hind paws (Fig. 1i–l). These data suggest that the tonic activation of nAChRs, such as α4β2 nAChRs, in the SNr controls pain thresholds. This may differ from our previous study showing that inhibition of SNr neurons does not change mechanical and thermal thresholds in naïve mice [28]. We argue that MEC and DHβE may affect the activity of a group of SNr neurons expressing high levels of nAChRs and being activated by endogenous ACh.

These results suggest that tonic activation of α4β2 nAChRs by endogenous ACh in the SNr may play an important role in controlling pain thresholds.

Nicotine in the SNr mitigates hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain

Our previous study shows that stimulation of SNr GABAergic neurons mitigates both acute and chronic pain [28]. We examined whether nAChR activation exerts analgesic effects on acute and chronic pain. We first established acute pain mouse model by injecting capsaicin (Cap) into either left or right lower hind leg of mice. We observed a lower PWT and a shorter PWL on both hind paws 15–30 min and 45–60 min later. Furthermore, injection of nicotine into the SNr in the right hemisphere (Fig. 2a, b) elevated PWT and PWL on both hind paws in Cap mice (Fig. 2d, e). These data prove that nicotine in the SNr mitigates hyperalgesia in Cap-induced acute nociceptive pain mouse model.

Fig. 2. Nicotine in the SNr mitigates hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain mouse models.

a Time line and schematic diagram of drug injection into the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) through a cannula. b Representative images showing injection of Alexa 488-conjugated Ctb into the SNr. Orange circles represent locations of cannulas. c Pain mouse models: chronic constriction injury (CCI) (n = 7) and spared nerve injury (SNI) (n = 7) of the sciatic nerve. d, e PWT and PWL on both hind paws of naïve and Cap mice 15–30 and 45–60 min after Cap injection and 15 min after injection of saline (Nic -) or nicotine (Nic +, 1 μM, 300 nl) into the SNr. f Time courses of PWT and PWL in sham mice (n = 7) and CCI mice (n = 7) before and after surgery. g PWT and PWL in CCI mice before and two weeks after surgery (without or with Nic injection into the SNr). h Time courses of PWT and PWL in sham mice (n = 7) and SNI mice (n = 7) before and after surgery. i PWT and PWL in SNI mice before and two weeks after surgery (without or with Nic injection into the SNr). One-way repeated measures ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used in (d, e, g, i). Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used in (f, h). ** P < 0.01.

We then established two chronic neuropathic pain mouse models with either chronic constriction injury (CCI) or spinal nerve injury (SNI) of the sciatic nerve on the left side (Fig. 2c). As illustrated in Fig. 2f, h, both CCI and SNI mice exhibited reduced PWT and PWL in the ipsilateral hind paw, while injection of nicotine into the contralateral SNr significantly elevated PWT and prolonged PWL (Fig. 2g, i) to levels close to those in sham mice. These data indicate that nicotine in the SNr mitigates hyperalgesia in chronic neuropathic pain.

Activation of α4β2 nAChRs mitigates hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain

We examined whether α4β2 nAChR agonist mimics nicotine effect on hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain. In capsaicin-induced acute nociceptive pain models, RJR-2403 was injected into the SNr in the right hemisphere 15 min before measurement of pain threshold. We observed that injection of RJR-2403 into the SNr increased c-Fos-(+) neurons in the SNr (Fig. 3a–c), indicating the enhancement of the activity of SNr neurons. Although nAChRs are vulnerable to desensitization upon exposure to their agonists [16, 17], our c-Fos-staining data support that RJR-2403 injection activates α4β2 nAChRs in the SNr. In behavioral tests, we found that RJR-2403 injection into the SNr elevated PWT and prolonged PWL on both hind paws of mice subjected to Cap injection into lower hind legs (Fig. 3d, e). Furthermore, co-injected with DHβE into the SNr, RJR-2403 did not exert analgesic effect in Cap-induced acute nociceptive pain mouse model (Fig. 3f, g). These data suggest that RJR-2403 in the SNr exerts analgesic effect through activating α4β2 nAChRs.

Fig. 3. Activation of α4β2 nAChRs mitigates hyperalgesia in acute and chronic pain.

a Diagram of drug injection into the SNr. b Representative images showing c-Fos-(+) SNr neurons in mice subjected to saline and RJR-2403 (RJR, 500 μM) injection. c Summary of c-Fos-(+) SNr neurons on both sides after saline or RJR injection. Contralateral, t = 6.37, P < 0.0001, n = 6; Ipsilateral, t = 13.25, P < 0.0001, n = 6. Two-tailed t tests. d, e PWT and PWL on both hind paws of Cap mice 15–30 and 45–60 min after Cap injection and 30 min after injection of saline(-) or RJR(+) into the SNr. f, g PWT and PWL on both hind paws of Cap mice (15–30 and 45–60 min after Cap injection) after injection of saline (-) or RJR (+) or RJR + DHβE into the SNr. h, i PWT and PWL after injection of saline (-) or RJR (+) into the SNr of CCI mice. j, k PWT and PWL after injection of saline (-) or RJR (+) into the SNr of SNI mice. l, m PWT and PWL after injection of saline (-) or ropinirole (Rop) or RJR + Rop into the SNr of CCI mice. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests were used in (d−m). ‘ns’ not significant. * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01.

In SNI and CCI mice (on left side), we observed that injection of RJR-2403 into the SNr in the right hemisphere significantly reversed both mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia on the left hind paw (Fig. 3h–k). According to Fig. 2b, drugs injected into the SNr may act on not only the principal GABAergic neurons but also dopaminergic neurons that are located in the ventral tier of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) [49, 50]. To clarify whether these dopaminergic neurons contribute to analgesic effect of RJR-2403, we injected ropinirole, a D2 receptor agonist, into the SNr to inhibit dopaminergic neurons [18, 51, 52]. Compared to CCI mice with saline or ropinirole injection into the SNr, CCI mice subjected to injection of ropinirole and RJR-2403 into the SNr showed significantly elevated PWT and prolonged PWL (Fig. 3l, m). These data suggest that inhibition of dopaminergic neurons did not dramatically attenuate the analgesic effect of RJR-2403 injected into the SNr. These results hint that GABAergic neurons may be major mediators of analgesic effect of RJR-2403 in the SNr.

Activation of α4β2 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons mitigates acute and chronic pain

To further confirm the role of α4β2 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons in pain modulation, we constructed Cre-dependent viral vectors carrying α4-shRNA (AAV-CMV-DIO-(EGFP-U6)-shRNA(Chrna4)-WPRE-hGH polyA) (shRNA) or scrambled RNA (AAV-CMV-DIO-(eGFP-U6)-shRNA(scramble)-WPRE-hGH polyA) (scrRNA). Three weeks after being injected into the SNr (Fig. 4a), we performed immunohistochemistry by GABA-antibody staining and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-antibody staining. We observed that the viral vector labeled neurons accounted for about half of SNr GABAergic neurons without overlapping with SNc dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 4b, c; Fig. S1a, b), and more than 90% of the virally labeled SNr neurons were GABAergic (Fig. 4b, c). Using quantitative real-time PCR assay, we found that transfection of shRNA (Chrna4) into SNr GABAergic neurons caused about 40%−50% downregulation of α4 mRNA without changing β2 and α7 mRNAs in the substantia nigra (Fig. S1c). To further analyze the changes of nAChR subunit mRNA in SNr GABAergic neurons, we utilized a laser capture apparatus to collect shRNA-eGFP-labeled neurons and scrRNA-eGFP-labeled neurons from 20 μm brain sections and analyzed mRNA levels of α4, β2, α7, Th, and Vgat genes with qRT-PCR. To visualize and collect SNc neurons with laser capture apparatus, we injected retrograde viral vector (AAV retro-hSyn-mCherry) into the subthalamic nucleus and captured mCherry-labeled SNc neurons. We observed that the transfection of shRNA-eGFP significantly downregulated mRNA of α4 and β2 in SNr GABAergic neurons (Fig. 4d; Fig. S1d), but not in SNc dopaminergic neurons (Fig. S1e, f).

Fig. 4. α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons modulate pain states in mice.

a Diagram for downregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons. b, c The specificity (left histogram) and efficiency (right histogram) of viral labeling of SNr GABAergic neurons. d mRNA of Vgat, α4, β2, α7, and Th in eGFP-labeled SNr GABAergic neurons in shRNA-injected mice (n = 6) and scrRNA-injected mice (n = 6). e, f 50 μM RJR-2403 (RJR)-evoked inward currents in SNr GABAergic neurons and SNc non-GABAergic neurons from shRNA (n = 5) and naive mice (n = 5). g PWT and PWL measured (15–30 min) before and after RJR injection into the SNr in shRNA mice (n = 7) subjected to Cap injection on the lower leg. h PWT and PWL measured (45–60 min) before and after RJR injection into the SNr in shRNA mice (n = 7) subjected to Cap injection on the lower leg. i PWT and PWL measured (15–30 min) before and after Nic injection into the SNr in shRNA mice (n = 7) subjected to Cap injection on the lower leg. j PWT and PWL measured (45–60 min) before and after RJR injection into the SNr in shRNA mice (n = 7) subjected to Cap injection on the lower leg. k PWT and PWL before and after injection of RJR into the SNr in shRNA (n = 6) mice subjected to SNI. l PWT and PWL before and after injection of Nic into the SNr in shRNA mice (n = 6) subjected to SNI. Two-tailed t tests were used in (d, f). One-way repeated measures ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests were used in (g−l). ‘ns’ not significant. * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01.

We also employed the whole-cell patch-clamp recording to measure α4 nAChR function in SNr and SNc neurons. In eGFP-labeled SNr neurons, puff (8 pSi, 1 s) of RJR-2403 (50 μM)-evoked inward currents in shRNA mice were reduced to about half of those in scrRNA mice (Fig. 4e, f). In contrast, in SNc neurons without eGFP (likely the principal dopaminergic neurons), RJR-2403 puff-evoked inward currents in shRNA mice had peak amplitudes similar to those in scrRNA mice (Fig. 4e, f). These data suggest that these viral vectors allow for cell-specific downregulation of α4β2 nAChRs in the SNr.

We further examined whether down-regulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons affects pain modulation by injection of RJR-2403 or nicotine into the SNr. We observed that in shRNA mice, RJR-2403 injection into the SNr lost its analgesic effect on Cap-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity (Fig. 4g, h); nicotine injection into the SNr exerted no effect on Cap-induced mechanical allodynia, but minor effect on Cap-induced thermal hypersensitivity (Fig. 4i, j). In shRNA mice subjected to SNI, injection of RJR-2403 into the SNr lost analgesic effects (Fig. 4k), whereas injection of nicotine into the SNr mitigated hyperalgesia in these mice (Fig. 4l).

These results suggest that α4 nAChRs in the SNr exert analgesic effect primarily by acting on GABAergic neurons, and α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons may play different roles in analgesic effect of nicotine in acute and chronic pain states.

Stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection mitigates hyperalgesia in mice with acute and chronic pain

Cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) are major sources of cholinergic inputs to the SNr [17, 53, 54]. Our preceding data show that exogenous nAChR agonist may activate SNr GABAergic neurons and modulate pain thresholds (Figs. 2, 3). We wondered whether stimulation of PPN cholinergic inputs to the SNr is sufficient to regulate mechanical and thermal thresholds. We then injected AAV-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP or AAV-EF1α-DIO-eYFP into the right PPN of ChAT-Cre mice and implanted an optical fiber into the right SNr (Fig. 5a–c). Although stimulation of the right PPN-SNr projection did not change PWT and PWL on either side in naïve mice (Fig. 5d–g), it elevated PWT and PWL on the left hind paw in mice subjected to Cap-injection on the left lower leg, but not on the right hind paw of mice subjected to Cap-injection on the right lower leg (Fig. 5h–k; Fig. S2a–d). Moreover, the analgesic effect of stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection on Cap-induced pain was attenuated by intraperitoneal injection of either MEC or DHβE (Fig. 5l–o). In SNI mice, stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection also elevated PWT and prolonged PWL on the contralateral side (Fig. 5p, q).

Fig. 5. Stimulating the PPN-SNr projection mitigates hyperalgesia in acute pain.

a Diagram and representative images showing optogenetic stimulation of the cholinergic projection from the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) to the SNr. b Summary of ChR2- and ChAT antibody-labeled PPN neurons. c A representative image showing an optical fiber in the SNr. d, e PWT and PWL on both hind paws before, during, and after blue light illumination of the PPN-SNr projection in ChR2 mice (n = 15). f, g PWT and PWL on both hind paws before, during, and after blue light illumination of the SNr in eYFP mice (n = 7). h, i PWT and PWL on both hand paws in Cap mice (n = 8) (45–60 min after Cap injection) before and during optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection. j, k PWT and PWL on both hand paws in eYFP mice (n = 7) (45–60 min after Cap injection) before and during blue light illumination of the SNr. l, m PWT and PWL in Cap mice before and during optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection without or with i.p. injection of mecamylamine (MEC) (n = 6). n, o PWT and PWL in Cap mice before and during optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection without or with i.p. injection of DHβE (n = 6). p, q PWT or PWL of SNI mice before and during optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection (n = 8). One-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used in (d−q). ‘ns’ not significant. ** P < 0.01.

These data suggest that endogenous cholinergic inputs to the SNr modulate pain thresholds in both acute and chronic pain via activating α4β2 nAChRs.

α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons regulates chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia

Consistent with previous studies [34–36], we observed that when we conducted subcutaneous injection of nicotine (0.5 mg/kg) to mice once per day for 2-3 weeks, the mice gradually developed mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity (Fig. 6a–c). Since previous studies demonstrated upregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons in chronic nicotine-treated mice [18, 55], we hypothesized that the hyperalgesia might be related to the upregulation of these receptors. To test this hypothesis, we injected Cre-dependent AAV viral vectors, carrying either Chrna4 mRNA (AAV-CMV-DIO-EGFP-U6-Chrna4-WPRE-hGH polyA) (Chrna4) or eGFP (AAV-CMV-DIO-EGFP-WPRE-hGH polyA) (eGFP) into the SNr of Vgat-Cre mice to overexpress α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons (Fig. 6d, e; Fig. S3a, b). We allow the mice recover for at least 3 weeks before we did the following experiments.

Fig. 6. The role of α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons in chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia in mice.

a Diagram for chronic subcutaneous injection of nicotine (Nic) or saline in mice and PWT and PWL was measured 5 h after injection. b, c PWT and PWL in chronic Nic mice (n = 8) and saline mice (n = 8). d, e AAV-CMV-DIO-Chrna4-eGFP was transfected in SNr GABAergic neurons. f mRNA levels of Vgat, α4, β2, α7, and Th in eGFP-labeled SNr GABAergic neurons in Chrna4 mice and eGFP mice was measured with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). g, h Representative traces and summary of RJR-evoked inward currents in SNr GABAergic and SNc non-GABAergic neurons from Chrna4 and eGFP mice. i Comparison of PWT and PWL in eGFP, Chrna4, and shRNA mice. j PWT and PWL in shRNA mice (n = 7) and scrRNA mice (n = 15) subjected to daily subcutaneous injection of Nic. k Diagram of chronic nicotine treatment, injection of Nic or RJR into the SNr, and pain behavior tests. l, m PWT in chronic nicotine mice before and after injection of Nic (n = 8) or RJR (n = 8) into the SNr. Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used in (b, c, j). Two-tailed t tests were used in (f, h). One-way ANOVA was used in (i). One-way repeated measures ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used in (i, l, m).

We observed that the transfection of Chrna4 increased the mRNA levels of α4 and β2 nAChR subunits to 5 and 2 folds in the substantia nigra respectively by quantitative real-time PCR assay of substantia nigra tissue (Fig. S3c) and to about 30 folds in SNr GABAergic neurons with quantitative real-time PCR assay of eGFP-labeled SNr neurons collected from 20 μm brain sections with a laser capture apparatus (Fig. 6f). On the contrary, the transfection of Chrna4 into the SNr did not change α4 and β2 nAChR mRNA levels in retrogradely labeled SNc neurons (Fig. S3e, f). Whole-cell patch-clamp recording demonstrated that transfection of Chrna4 into SNr GABAergic neurons enhanced the peak amplitude of RJR-evoked inward currents by 3 folds in SNr GABAergic neurons, but did not change the peak amplitude of RJR-evoked inward currents in SNc non-GABAergic neurons (Fig. 6g, h).

The mechanical and thermal thresholds in these mice were similar to naïve mice (Fig. 6i). This phenomenon was also observed in mice subjected to shRNA transfection into SNr GABAergic neurons to downregulate α4 nAChRs (Fig. 6i). Therefore, neither upregulation nor downregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons affects baseline mechanical and thermal pain thresholds. These data suggest that the upregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons may not directly cause hyperalgesia in chronic nicotine mice. In contrast to shRNA mice (Fig. 4), Chrna4 mice retained analgesic effects of nAChR agonists in acute and chronic pain states (Fig. S4a-l).

To elucidate whether α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons are involved in the development of chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia, we set up cohorts of mice subjected to injection of viral vector carrying either shRNA or scrambled RNA (scrRNA) of α4 nAChR subunit into the SNr of Vgat-Cre mice, and exposed these mice to chronic nicotine. We observed that chronic nicotine reduced both PWT and PWL in scrRNA mice, but not in shRNA mice (Fig. 6j). Thus, α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons are essential for the development of chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia. Taken these data together with those in Figs. 2–4 showing that inhibition of nAChRs reduced mechanical and thermal thresholds, it is reasonable to postulate that chronic nicotine-induced allodynia may come from persistent desensitization of nAChRs. To test this speculation, we implanted a cannula above the SNr to administer nicotine or RJR-2403 into chronic saline or nicotine treated-mice (Fig. 6k). We observed that injection of either nicotine or RJR-2403 into the right SNr improved mechanical allodynia and thermal hypersensitivity on both hind paws in chronic nicotine-treated mice (Fig. 6l, m; Fig. S4m, n). In this circumstance, α4 nAChRs in the SNr may be activated because the activation of α4 nAChRs in the SNr confers analgesic effect in pain states (Figs. 2, 3, 5). Therefore, chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia does not cause a persistent desensitization of α4β2 nAChRs in the SNr, which may not be an immediate cause of hyperalgesia in chronic nicotine-treated mice.

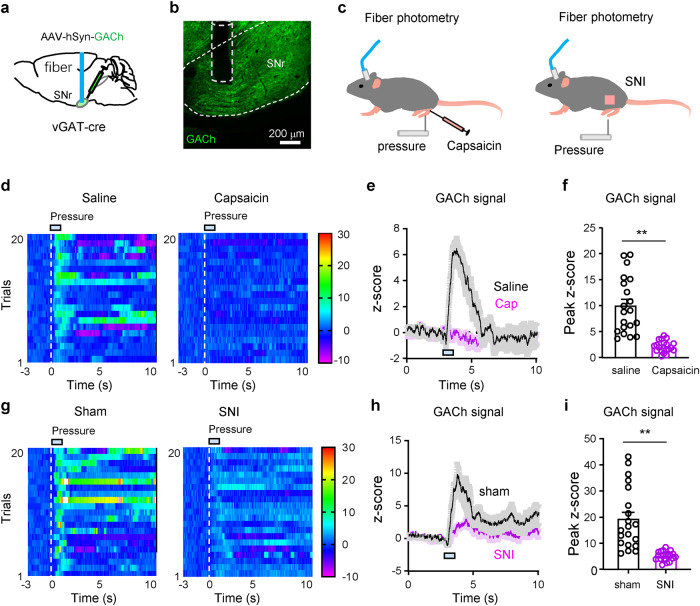

ACh release in the SNr is attenuated in mice subjected to chronic nicotine exposure, and acute and chronic pain

The release of endogenous ACh is an important component for cholinergic inputs. To understand whether chronic nicotine affects ACh release in the SNr, we transfected AAV-hSyn-GACh, a green fluorescent ACh sensor [56, 57], into the SNr to monitor ACh release with fiber photometry (Fig. 7a, b). We observed that mechanical stimulation on the tail evoked less ACh release in the SNr in chronic nicotine-treated mice than in chronic saline-treated mice (Fig. 7c–f). These data further support that ACh deficiency in the SNr may be an important pathophysiology associated with hyperalgesia in chronic nicotine-treated mice. We then enhanced endogenous cholinergic inputs from the PPN to the SNr with optogenetic technique (Fig. 7g). Although optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection did not alter PWT and PWL in chronic saline mice, it increased PWT and PWL on the contralateral hind paw in chronic nicotine-treated mice, but not those on the ipsilateral hind paw (Fig. 7h–k). These data suggest that reduction of ACh release may be relevant to chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia.

Fig. 7. Chronic nicotine reduces ACh release in the SNr.

a, b Diagram and a representative image for fiber photometry recording of fluorescence intensity of ACh sensor (GACh) in the SNr. c Pressure (3 s, 200 g/mm2) on tail induced ACh release in the SNr. d Heat maps showing pressure-induced ACh release in the SNr. e, f Summarized pressure-induced changes in GACh signal. e Two tailed t test. f Mann-Whitney test. g Representative images showing optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr cholinergic projection. h PWT on both hind paws before and during light stimulation in chronic saline mice (n = 7). i PWT on both hind paws before and during light stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection in chronic Nic mice (n = 8). j PWL on both hind paws before and during light stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection in chronic saline mice (n = 7). k PWL on both hind paws before and during light stimulation in chronic Nic mice (n = 8). One-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used in (h−k). ‘ns’ not significant. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

To determine whether reduction of ACh release occurs in acute and chronic pain states, we performed fiber photometry recordings of the GACh signal in the SNr of mice subjected to either capsaicin-injection into the lower hind leg or SNI (Fig. 8a–c). We observed that mechanical stimulation of the hind paw evoked much smaller increase of ACh release in the SNr in capsaicin-induced nociceptive pain and SNI mice than saline-treated or sham mice (Fig. 8d–i). These results may explain why stimulation of the PPN-SNr cholinergic projection elevates pain thresholds in acute and chronic pain mice, but not in naïve mice.

Fig. 8. Pain stimulation-induced ACh release in the SNr is reduced in capsaicin nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain.

a, b Diagram and a representative image for fiber photometry recording of fluorescence intensity of ACh sensor (GACh) in the SNr. c GACh signal was monitored with fiber photometry before (3 s), during, and after hind paw pressure (2 s, 200 g/mm2) was applied on the hind paw in capsaicin-evoked nociceptive pain mice and SNI mice. d Heat maps showing hind paw pressure-induced ACh release in the SNr in saline- or capsaicin-injected mice. e, f Summarized traces and amplitudes of pain-stimulation-induced changes in GACh signal. g Heat maps showing hind paw pressure-induced ACh release in the SNr in sham and SNI mice. h, i Summarized traces and amplitudes of pain-stimulation-induced changes in GACh signal in the SNr. Two-tailed t test for (f, i). **P < 0.01.

Considering that motor function may affect pain response in mice, we performed the open field test in mice and observed that pharmacological activation of nAChRs with either nicotine or RJR-2403, optogenetic stimulation of the PPN-SNr cholinergic terminals, pharmacological inhibition of nAChRs with DHβE, and viral vector-assisted overexpression of α4 subunit did not change locomotion in mice (Fig. S5). The only exception is that down-regulation of α4 subunit in SNr GABAergic neurons significantly enhanced locomotion. The underlying mechanisms need further investigation. Therefore, the overall pain modulation effects by α4 nAChRs in the present study are not confounded by the alterations in motor function.

Discussion

nAChRs are widely distributed in the central nervous system, including ascending and descending pain pathways [8, 10, 11, 58]. Accumulating evidence reveals the complexity of pain modulation by nAChRs. The outcomes (i.e., hyperalgesia, no effect, or analgesia) depend on the locations (brain regions and neuron types) and subtypes of nAChRs [8, 11, 58]. Several subtypes of nAChRs are highly expressed in the midbrain, especially in the ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra [14, 15, 18, 22, 25]. These brain regions do not belong to the classical pain modulation pathways. Emerging studies have implicate dopaminergic system originated from the ventral tegmental area in pain modulation [46, 47, 59, 60]. However, pain modulation by nAChRs in the substantia nigra has been understudied.

Recently, we demonstrated that SNr GABAergic neurons regulate hyperalgesia in acute pain and chronic neuropathic pain [28, 29, 37]. As nAChRs were established as effective modulators of SNr neurons [18, 22], they may regulate pain thresholds through SNr neurons. The present study provides evidence to support this hypothesis. First, in naïve mice, inhibition of nAChRs, especially α4β2 nAChRs, reduced both mechanical and thermal thresholds. Second, in acute nociceptive pain and chronic neuropathic pain states, hyperalgesia was mitigated by pharmacological activation of α4β2 nAChRs in the SNr and by optogenetic stimulation of endogenous cholinergic inputs to the SNr. Third, α4β2 nAChR agonist still relieved chronic neuropathic pain when dopaminergic neurons were inhibited by a D2 receptor agonist. Fourth, in mice whose α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons were down-regulated, RJR-2403 lost its analgesic effects in acute and chronic pain states. These data suggest that α4β2 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons may be potential targets to treat pain symptoms.

Our previous studies reveal the heterogeneity of SNr GABAergic neurons in terms of pain modulation [28, 37]. In naïve mice, optogenetic stimulation of glutamatergic inputs from the subthalamic nucleus (STN) to the SNr to excite some SNr neurons reduces thermal threshold in naïve mice; while photostimulation of SNr GABAergic neurons exert no effect on both mechanical and thermal thresholds in naïve mice. These inconsistent results may be partially explained by our previous finding that SNr neurons projecting to the subthalamic nucleus and those innervated by the subthalamic nucleus are largely separated [28]. Thus, modulating different neuronal populations in the SNr may lead to different effects on pain threshold. In the present study, we observed that inhibition of nAChRs, especially α4β2 nAChRs, in the SNr reduced pain thresholds. It is noteworthy that nAChR antagonists may perturb preferentially the activity of a group of SNr neurons receiving strong endogenous cholinergic innervation and expressing high levels of nAChRs. In acute inflammatory pain and chronic neuropathic pain models, our data show that activation of nAChRs, primarily α4β2 nAChRs, by injecting exogenous agonist in the SNr or optogenetically stimulating endogenous cholinergic input to the SNr, mitigated hyperalgesia through regulating SNr GABAergic neurons. Although the diversity of SNr GABAergic neurons poses uncertainty to predict pain modulation outcomes by a particular group of neurons, our data hint that activation of α4β2 nAChRs in the SNr may recruit a group of SNr GABAergic neurons being able to mitigate pain symptoms in both acute and chronic pain.

Chronic nicotine modifies the circuit of the substantia nigra [18, 22, 61, 62]. It upregulates α4β2 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons, but not in SNc dopaminergic neurons. This cell-specific upregulation leads to hyperactivity of SNr GABAergic neurons and hypoactivity of SNc dopaminergic neurons. This circuit pattern may explain protection of SNc dopaminergic neurons from excitotoxicity by chronic nicotine [61]. In the present study, we observed that neither overexpression nor downregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons regulated pain thresholds in naïve mice. These data suggest that mere changes in these receptors do not replicate hyperalgesia in chronic nicotine-treated mice. It is noteworthy that viral vector-assisted gradual modulation of α4 nAChRs may mobilize compensatory machinery to maintain normal pain thresholds. This may explain why gradual downregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons did not reduce pain thresholds in naïve mice similarly to immediate inhibition of these receptors with nAChR antagonists. Interestingly, the downregulation of α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons eliminated chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia. These data suggest that the interaction between chronic nicotine and α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons may play an important role in hyperalgesia phenotype.

Considering that besides the biophysical property and number of nAChRs, endogenous ACh levels in the SNr is an additional key factor to determine the function of α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons, which may be involved in chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia. This hypothesis is supported by our fiber photometry data showing that after chronic nicotine treatment, ACh release in the SNr in response to in vivo pain stimulation was significantly attenuated. Indeed, in the present study, we observed that in chronic nicotine-treated mice, either microinjection of nAChR agonist into the SNr or stimulation of the PPN-SNr projection elevated pain thresholds. Together with our finding that enhancement of the function of α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons either optogenetically or pharmacologically can mitigate chronic nicotine-induced hyperalgesia, these data hint that pain stimulation-induced ACh release in the SNr may play an important role in determining pain thresholds; chronic nicotine compromises this presynaptic machinery and reduces pain thresholds. This may be also applicable to interpret the hyperalgesia in capsaicin-induced nociceptive pain and SNI because pain-stimulation-induced ACh release was attenuated in these mouse models.

We also provided evidence supporting that α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons may play different roles in acute and chronic pain. In shRNA mice, RJR injection into the SNr lost its analgesic effects in both acute and chronic pain mouse models; nicotine injection into the SNr only slightly increased thermal threshold in Cap mice, but dramatically increased mechanical and thermal thresholds in SNI mice. These data suggest that non-α4 nAChRs in the SNr may also be modified in chronic pain and serve as potential analgesic targets, complementary to α4 nAChRs. As chronic nicotine affects both nAChRs and ACh release, which may interplay to confer hyperalgesia, it is noteworthy that chronic pain may modify both nAChRs and ACh release. Further investigation is needed to address this possibility.

In summary, we provide evidence to support the notion that α4 nAChRs on SNr GABAergic neurons are involved in pain modulation under some conditions with hyperalgesia as a major manifestation. In naïve mice, α4 nAChRs receptors may contribute to the maintenance of pain thresholds because inhibition, but not activation, of these receptors regulates pain thresholds. In acute and chronic pain states, activation of these receptors mitigates hyperalgesia, probably due to neuroadaptation in SNr circuits, such as reduction of ACh release. Furthermore, the interplay between α4 nAChRs and ACh release may be important for the manifestation of hyperalgesia in chronic nicotine treated, acute nociceptive, and chronic neuropathic pain conditions. The present study suggests that α4 nAChRs in SNr GABAergic neurons may be effective therapeutic targets for treatment of both acute and chronic pain and for intervention to mitigate hyperalgesia during smoking cessation.

Supplementary Information

Supplemental information titles and legends

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071231 (CX), 81971038 (CYZ), 82171235 (CYZ), 82271293 (CX), 82371242 (CYZ)), the Fund for Jiangsu Province Specially Appointed Professor (CX, CYZ), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20211349, CYZ), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (23KJA320006 (CYZ), 23KJA320007, (CX)), and the Leadership Program in Xuzhou Medical University (JBGS202203, CX). We thank Terrence Z.Y. Xiao for data organization and grammar check for the manuscript.

Author contributions

CX, CYZ and SL designed the experiments. CX and CYZ supervised this research. YH, JQZ, YWL and YJ performed mouse survival surgeries and morphological experiments. YH, JQZ, SYL, YWL, CY and YJ performed behavioral tests and managed the mouse colony. YWJ and HZG collected and analyzed electrophysiological data. CX, CYZ and YH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yu Han, Jia-qi Zhang

Contributor Information

Chun-yi Zhou, Email: chunyi.zhou@xzhmu.edu.cn.

Cheng Xiao, Email: xchengxj@xzhmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-024-01234-7.

References

- 1.Busse JW, Wang L, Kamaleldin M, Craigie S, Riva JJ, Montoya L, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:2448–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hylands-White N, Duarte RV, Raphael JH. An overview of treatment approaches for chronic pain management. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noori A, Sadeghirad B, Wang L, Siemieniuk RAC, Shokoohi M, Kum E, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of individual opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins C, Smith BH, Matthews K. Evidence of opioid-induced hyperalgesia in clinical populations after chronic opioid exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:e114–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koller G, Schwarzer A, Halfter K, Soyka M. Pain management in opioid maintenance treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:1993–2005. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1652270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noori SA, Aiyer R, Yu J, White RS, Mehta N, Gulati A. Nonopioid versus opioid agents for chronic neuropathic pain, rheumatoid arthritis pain, cancer pain and low back pain. Pain Manag. 2019;9:205–16. doi: 10.2217/pmt-2018-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dulawa SC, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic regulation of mood: from basic and clinical studies to emerging therapeutics. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:694–709. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naser PV, Kuner R. Molecular, cellular and circuit basis of cholinergic modulation of pain. Neuroscience. 2018;387:135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schechtmann G, Song Z, Ultenius C, Meyerson BA, Linderoth B. Cholinergic mechanisms involved in the pain relieving effect of spinal cord stimulation in a model of neuropathy. Pain. 2008;139:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umana IC, Daniele CA, McGehee DS. Neuronal nicotinic receptors as analgesic targets: it’s a winding road. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:1208–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umana IC, Daniele CA, Miller BA, Abburi C, Gallagher K, Brown MA, et al. Nicotinic modulation of descending pain control circuitry. Pain. 2017;158:1938–50. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji YW, Shen ZL, Zhang X, Zhang K, Jia T, Xu X, et al. Plasticity in ventral pallidal cholinergic neuron-derived circuits contributes to comorbid chronic pain-like and depression-like behaviour in male mice. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37968-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks MJ, Grady SR, Salminen O, Paley MA, Wageman CR, McIntosh JM, et al. α6β2*-subtype nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are more sensitive than α4β2*-subtype receptors to regulation by chronic nicotine administration. J Neurochem. 2014;130:185–98. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, et al. Nicotine activation of α4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wooltorton JR, Pidoplichko VI, Broide RS, Dani JA. Differential desensitization and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in midbrain dopamine areas. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3176–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03176.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J. Understanding of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:653–5. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao C, Zhou CY, Jiang JH, Yin C. Neural circuits and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediate the cholinergic regulation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons and nicotine dependence. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41401-019-0299-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nashmi R, Xiao C, Deshpande P, McKinney S, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, et al. Chronic nicotine cell specifically upregulates functional α4* nicotinic receptors: basis for both tolerance in midbrain and enhanced long-term potentiation in perforant path. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8202–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2199-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buisson B, Bertrand D. Chronic exposure to nicotine upregulates the human α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor function. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1819–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01819.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGranahan TM, Patzlaff NE, Grady SR, Heinemann SF, Booker TK. α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic neurons mediate nicotine reward and anxiety relief. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10891–902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, et al. Acetylcholine receptors containing the β2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391:173–7. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao C, Nashmi R, McKinney S, Cai H, McIntosh JM, Lester HA. Chronic nicotine selectively enhances α4β2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12428–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2939-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C, et al. Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7820–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07820.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klink R, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Zoli M, Changeux JP. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1452–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estakhr J, Abazari D, Frisby K, McIntosh JM, Nashmi R. Differential control of dopaminergic excitability and locomotion by cholinergic inputs in mouse substantia nigra. Curr Biol. 2017;27:1900–14.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metaxas A, Bailey A, Barbano MF, Galeote L, Maldonado R, Kitchen I. Differential region-specific regulation of α4β2* nAChRs by self-administered and non-contingent nicotine in C57BL/6J mice. Addict Biol. 2010;15:464–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miwa JM, Freedman R, Lester HA. Neural systems governed by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: emerging hypotheses. Neuron. 2011;70:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin C, Jia T, Luan Y, Zhang X, Xiao C, Zhou C. A nigra-subthalamic circuit is involved in acute and chronic pain states. Pain. 2022;163:1952–66. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia T, Wang YD, Chen J, Zhang X, Cao JL, Xiao C, et al. A nigro-subthalamo-parabrachial pathway modulates pain-like behaviors. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7756. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35474-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2021: addressing new and emerging products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 31.Wipfli H, Samet JM. One hundred years in the making: the global tobacco epidemic. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:149–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Biasi M, Dani JA. Reward, addiction, withdrawal to nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:105–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J. Double target concept for smoking cessation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1015–8. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson KL, Pinkerton KE, Uyeminami D, Simons CT, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Antinociception induced by chronic exposure of rats to cigarette smoke. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, Warner DO. Smoking and pain: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:977–92. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alfonso-Rodriguez J, Wang S, Zeng X, Candiotti KA, Zhang Y. Mechanism of electroacupuncture analgesia on nicotine withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia in a rat model. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2022;2022:7975803. doi: 10.1155/2022/7975803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luan Y, Tang D, Wu H, Gu W, Wu Y, Cao JL, et al. Reversal of hyperactive subthalamic circuits differentially mitigates pain hypersensitivity phenotypes in parkinsonian mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:10045–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916263117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2nd, Editor. (Academic Press, San Diego, 2001).

- 39.Wang D, Liu P, Mao X, Zhou Z, Cao T, Xu J, et al. Task-demand-dependent neural representation of odor information in the olfactory bulb and posterior piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2019;39:10002–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1234-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H, Yan X, Tang D, Gu W, Luan Y, Cai H, et al. Internal states influence the representation and modulation of food intake by subthalamic neurons. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:1355–68. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang YK, Lu YG, Zhao X, Zhang JB, Zhang FM, Chen Y, et al. Cytokine activin C ameliorates chronic neuropathic pain in peripheral nerve injury rodents by modulating the TRPV1 channel. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:5642–57. doi: 10.1111/bph.15284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou C, Luo ZD. Nerve injury-induced calcium channel α2δ1 protein dysregulation leads to increased pre-synaptic excitatory input into deep dorsal horn neurons and neuropathic allodynia. Eur J Pain. 2015;19:1267–76. doi: 10.1002/ejp.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixon WJ. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:441–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN. Peripheral and central mechanisms of cutaneous hyperalgesia. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:397–421. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90027-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87:149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Qian YL, Li C, Liu D, Wang L, Wang XY, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the mesolimbic reward circuitry mediates nociception in chronic neuropathic pain. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82:608–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang HR, Hu SW, Zhang S, Song Y, Wang XY, Wang L, et al. KCNQ channels in the mesolimbic reward circuit regulate nociception in chronic pain in mice. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:597–610. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00668-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou C, Gu W, Wu H, Yan X, Deshpande P, Xiao C, et al. Bidirectional dopamine modulation of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to subthalamic neuron subsets containing α4β2 or α7 nAChRs. Neuropharmacology. 2019;148:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan JP, Geng HZ, Ji YW, Jia T, Treweek JB, Li AA, et al. Age-dependent alterations in key components of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system and distinct motor phenotypes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:862–75. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00713-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao C, Cho JR, Zhou C, Treweek JB, Chan K, McKinney SL, et al. Cholinergic mesopontine signals govern locomotion and reward through dissociable midbrain pathways. Neuron. 2016;90:333–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grace AA, Onn SP. Morphology and electrophysiological properties of immunocytochemically identified rat dopamine neurons recorded in vitro. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3463–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03463.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacey MG, Mercuri NB, North RA. Two cell types in rat substantia nigra zona compacta distinguished by membrane properties and the actions of dopamine and opioids. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1233–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-04-01233.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benarroch EE. Pedunculopontine nucleus: functional organization and clinical implications. Neurology. 2013;80:1148–55. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182886a76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mena-Segovia J, Bolam JP. Rethinking the pedunculopontine nucleus: from cellular organization to function. Neuron. 2017;94:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao C, Miwa JM, Henderson BJ, Wang Y, Deshpande P, McKinney SL, et al. Nicotinic receptor subtype-selective circuit patterns in the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:3734–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3528-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jing M, Li Y, Zeng J, Huang P, Skirzewski M, Kljakic O, et al. An optimized acetylcholine sensor for monitoring in vivo cholinergic activity. Nat Methods. 2020;17:1139–46. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0953-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jing M, Zhang P, Wang G, Feng J, Mesik L, Zeng J, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent acetylcholine indicator for in vitro and in vivo studies. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:726–37. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carstens E, Carstens MI. Sensory effects of nicotine and tobacco. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24:306–15. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu D, Tang QQ, Wang D, Song SP, Yang XN, Hu SW, et al. Mesocortical BDNF signaling mediates antidepressive-like effects of lithium. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1557–66. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-0713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu D, Tang QQ, Yin C, Song Y, Liu Y, Yang JX, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated projection-specific regulation of depressive-like and nociceptive behaviors in the mesolimbic reward circuitry. Pain. 2018;159:175. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lester HA, Xiao C, Srinivasan R, Son CD, Miwa J, Pantoja R, et al. Nicotine is a selective pharmacological chaperone of acetylcholine receptor number and stoichiometry. Implications for drug discovery. AAPS J. 2009;11:167–77. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nashmi R, Lester H. Cell autonomy, receptor autonomy, and thermodynamics in nicotine receptor up-regulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental information titles and legends