The government white paper The New NHS, published in December 1997,1 reaffirmed the NHS Executive’s commitment to an NHS-wide electronic network. The network was originally conceived in essentially administrative terms, but it is now to be used to support clinical work. Now is therefore a good time to consider the future direction of NHS networking. This article focuses on the economic and political issues of electronic networks in primary care and considers two questions. Firstly, can the benefits of networks outweigh the costs, or are they simply poor investments? Secondly, if a case can be made, then what problems will need to be addressed in the new networking strategy?

Summary points

The NHS computer network, NHSnet, was originally oriented towards administration but is now to be designed to support clinical work

It is possible to construct a positive case for a large scale network for healthcare settings, based mainly on economic arguments

It is also possible to identify conditions that need to be met before the positive case can be translated into reality

Some of these conditions could be met in the near future, but others will require changes in attitudes and values that will have to be tackled in the longer term

Assessment of the chances of success of an NHS-wide network is hampered by a lack of empirical evidence about the costs and benefits of networks in health care

Background

Implementation of the 1992 information management and technology strategy2 was slower than the NHS Executive originally hoped.3,4 Concern has been expressed about elements of the strategy, notably about data security5 and the failure to show that the investments made to date have been worth while.6 It has been claimed that the strategy will save £100m a year,7 but after five years there is no firm published evidence that any money has been saved.

A key element of the strategy was a dedicated national network service (called NHSnet) linking databases in general practices, NHS trusts, health authorities, and elsewhere. The concept was that data could be accessed wherever it was needed within the NHS, subject to security and other safeguards. The service is available and in principle can be used to exchange many different types of data, but, crucially, few general practices are linked to it. Most general practices do, however, have links to health authorities via local networks for exchanging limited administrative data such as items of service claims, but they cannot exchange clinical data with other sites. The two systems are not currently compatible with each other, so persuading general practitioners to move to using NHSnet is a complicated matter. A third option, the internet, is used by some general practitioners for email and other purposes. The relative costs and benefits to general practitioners of these different networks are difficult to compare because they are used for different purposes.

The New NHS signals a move away from a concern with networks for administration to networks to support clinical work, and hence use of NHSnet by general practitioners and other clinicians. The major task of creating a clinically focused national network has thus formally begun. This article considers the issues from the point of view of a key service provider, the general practitioner. The first section puts a positive, somewhat idealised, case for networking based mainly on economic arguments,8,9 while the next section outlines key challenges.

The case for networking

Imagine that you work in a general practice with an aging computer system and are considering whether to join a local network. One course of action might be to undertake a literature review. Systematic reviews of general practice systems10 and those used in other clinical settings11–13 have found only limited evidence of positive changes. Major NHS computing initiatives have run into serious problems.14,15 There is little reliable information about the costs or benefits of networks.16

Given this problem, you might instead assess the volume of data “traffic” currently going in and out of the practice (see table) to establish what types of data might bring benefits if exchanged electronically. For example, a typical general practitioner writes some 40-50 prescriptions a week.6 These are helpful figures, though it is not known how much of the information is really important clinically or in managing the practice.

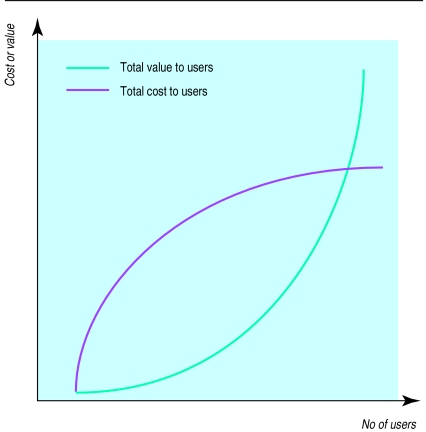

The practice might therefore generate a set of arguments about the costs and benefits of networks (see box for an example). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the central concept, which is that the bulk of the investment costs are incurred early on in the development of a network (perhaps in the range of £1m to £3m for the area of a health authority) and tail off as the network grows. Conversely, the initial benefits are modest and grow only when the number of users increases, exceeding the costs when a “critical” number of users is reached. In practical language, it is too expensive for individual practices to fund links to local trusts and other sites on their own. If, however, they share the investment costs with a large enough number of local practices, trusts, and the local health authority the investment costs become more affordable.

Sources of resource savings

Cases for new investments in computers and networks are usually based on the assumption that they will substitute for paper based systems. In healthcare settings the main source of such benefits is likely to be when networks reduce communication time or costs, compared with using the post or faxes. The time related effects will be important when providing information sooner is likely to lead to better service or patient outcomes. Note that the empirical evidence for savings from substitution is weak,5 and it seems quite possible that linking to a large network may increase ease of communication and hence the volume of messages that practices have to deal with. Another source of benefits that is rarely mentioned is economies of scope and scale. This is understandable because we have almost no information on the size of any effects, but in principle they may be considerable. The larger a network becomes, both in scale (the number of users) and scope (the number of different uses it can be put to), the lower the costs and the greater the value of the network for each user.17 These effects are thought to underlie the massive reduction in the costs of communications by telephone, and increasingly by computer, in our everyday lives.

Figure 1.

Changes in total cost and value of network as number of users increases. The costs of implementing the network are high initially, but the rate of increase in costs falls once the main elements are in place, and the additional cost of linking new users is relatively low. Conversely, the benefits are modest initially but increase as the number of users increases. For the right design and implementation strategy, and sufficient users, the curves eventually cross so that the value exceeds the cost

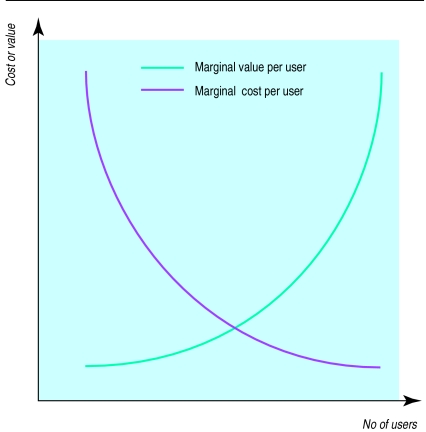

Figure 2.

Marginal cost and value of network for individual users as number of users increases. From the perspective of a general practice, the marginal cost of using a network decreases as it grows in size because there are more users to share the investment and running costs—as long as any savings are passed on to users and not retained entirely by suppliers. The value of the network increases with increasing size, as the network allows users to benefit from new services that can be made available

Figure 2 shows that, as the number of users increases, the marginal cost of using the system falls and the value of using it increases, again to a point when the benefits outweigh the costs. If this analysis is correct, one implication for general practitioners is that they need to implement systems so as to maximise early financial and service benefits, to ensure they get to the “critical” point before they run out of money. Another is that some applications cannot be justified early on but may be justified later, once the network is largely completed, because the additional cost of providing them is then relatively small. Creating links to sources of good practice guidance cannot by itself justify the initial investment in a network, but it might be justified once the network is up and running.

Complications

If these arguments are correct, why isn’t everyone linked already? Five key economic and political complications that are discussed here will have to be addressed if a new national strategy is to be successful. A sixth, data security, has been discussed elsewhere.5,18

Evaluation: informing investment decisions

—If the cost and benefits of systems had been clearly demonstrated by now, it might be reasonable to expect general practitioners and others to make investments in electronic networks themselves; but the evidence is not available, and central guidance does not reflect the arguments in the previous section.19 There are currently risks that bad investments will be made, with substantial sums of money, because there is little reliable evaluative information available to local sites. It is important not to proceed on the basis of the theoretical case advanced earlier. After all, electronic networks might serve to speed up the provision of unnecessary services, such as requests for unnecessary tests, at the same time as supporting tangible improvements in service.

Who pays?

—The NHS faces basic questions about who pays for initial connections and for the ongoing costs of using the network. The most sensible solution would seem to be a balance of national and local funding, but these are straitened times for the NHS, and, even if general practitioners were given generous support for networking, the total financial and time costs for practices would be substantial.

Who owns clinical and management data?

—Problems of data ownership have bedevilled the information management and technology strategy and other information related initiatives in recent years.18 The advent of large scale networks requires the NHS to revisit the debate, because formal decisions have to be made about where to store data and about rights of access to it. This goes to the heart of debates about the merits of shared patient records, about patients’ access to data about themselves, and other issues of ownership. The new strategy needs solutions that have been negotiated with all interested parties.

Collective action

—The next problem is getting people to act in a coordinated way to maximise the value of any network. Broadly, the better the coordination the more successful the network. However, multi-professional and multi-agency working has proved difficult in other initiatives and seems likely to be a limiting factor in the rate of progress of any networking strategy. A new strategy will therefore have to take into account the costs of encouraging those with reservations and the problems caused by those who do not want to participate. This is not a trivial issue, impinging as it does on differences in values and beliefs within and between different types of clinician and manager. This leads to questions about ways of achieving the necessary coordination. Central efforts will have to be balanced by a new approach to encourage local initiatives: many of the benefits will be found in and near patient care settings, so this is where effort now needs to be focused.20

Regulation: protecting patients’ and NHS interests

—Any new strategy must include protection of the interests of the NHS and of patients. In the case of networking this might include encouraging or discouraging suppliers in particular markets, and setting technical standards that suppliers have to comply with. Without a regulator there is a risk that suppliers of networks or key services may have a monopoly and perhaps charge general practitioners excessive fees.

Conclusion

An economic case can be made for electronic networks in the NHS, although the arguments are necessarily qualitative and theoretical in nature. Equally, though, there are several issues that have helped to slow the progress of networking in the NHS and which will have to be tackled in the new national strategy. A more clinical focus for NHS networking is welcome: an agenda for large economic and organisational change has now to be tackled.

Further reading

Allan D, Quinlan C. Making sense of computers in general practice. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1995

Preece J. The use of computers in general practice. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994

Netlines

Technical Advisory Service for Images (TASI)

• In view of the recent discussion in the BMJ about digital images and informed consent, readers might be interested to visit the TASI website (www.tasi.ac.uk), which provides advice on the ethical, technical, and copyright aspects of setting up digital image archives.

British Official Publications Current Awareness Service (BOPCAS)

• The BOPCAS website (www.soton.ac.uk/∼bopcas/index.html) allows you to browse or search lists of UK parliamentary or departmental publications indexed by date, publication type, and policy area. There are several associated mailing lists available via the mailbase server (www.mailbase.ac.uk/alphabetical/b.html).

EMBBS Electrocardiogram of the Month

• The EMBBS Electrocardiogram of the Month (www.embbs.com/ekg/ekg.html) features a collection of challenging ECGs (in US parlance, EKGs) with diagnosis and analysis. On the same site is the EKG File Room on www.embbs.com/ekg/fileroom.html.

DocTalk Radio

• DocTalk (medworld.stanford.edu/radio/) is weekly radio programme produced by medical students at Stanford University. You can listen to it over the net, but you will need to have the RealAudio Player software (available from www.realaudio.com/products/player/).

Anatomy tutorials

• Donal Shanahan at the University of Newcastle has produced three interactive tutorials (numedsun.ncl.ac.uk/∼nds4/tutorials/index.html) on the gross anatomy of the shoulder, larynx, and vertebral column. Aimed at first year medical students, they include diagrams, dissection images, magnetic resonance images, text, and movies.

Orthogate

• Orthogate (www.orthogate.com) boasts that it provides all the orthopaedic information that you could need from the internet. The site certainly has an international feel, with a European version on www.belgianorthoweb.be/orthogate/, a version in French on www.belgianorthoweb.be/orthogate/index_fr.htm, and a link to IndiaOrth (indiaorth.simplenet.com/orth/index.htm), a mailing list for Indian surgeons.

Internet porn: set a thief to catch a thief?

• While the internet is by and large a force for good, its down side includes the exchange of pornography by paedophiles and the malevolent activities of some hackers. It is thus intriguing to see that some hackers are using their skills for good rather than ill. Ethical Hackers Against Pedophiles (www.hackers.com/ehap/) is a group who claim that theirs is “a mission of good over evil” and that “this is war.” It is hard to disagree with their stated aim of seeking out and stopping exploitation of children on the internet, but does the end justifies the means?

Internet porn: are you re-publishing it?

• While adult pornography may not be as clearly illegal or unethical as child pornography, most, if not all, British medical schools have a policy of banning it from their computers and networks. It thus seems odd that many of the same institutions still accept and re-broadcast a wide range of newsgroups covering the rawer aspects of human sexuality (particularly those in the alt.sex hierarchy, which covers everything from news:alt.sex.bestiality to news:alt.sex.incest). If you can access these newsgroups over your university network you might want to ask those in authority why.

Babelfish

• A fashionable office ruse used to be to put colleagues’ names through a spellchecker program to see how they got mangled. The latest internet fashion is to feed web pages or other text to Alta-vista’s Babelfish (babelfish.altavista.digital.com/cgi-bin/translate?) and see how it performs. The website allows you to translate from English to five other European languages and vice versa. Despite some amusing gaffes, it does well enough to be useful much of the time. Try turning the BMJ into French (babelfish.altavista.digital.com/cgi-bin/translate?languagepair=ef&urltext=http%3a%2f%2fwww%2ebmj%2ecom%2fcurrent%2eshtml) or compare Babelfish’s attempts to translate the Pasteur Institute’s web pages (www.pasteur.fr) with their official English language versions. Alternatively, you could try learning Esperanto (wwwtios.cs.utwente.nl/esperanto/).

Compiled by Mark Pallen email m.pallen@qmw.ac.uk web page www.medmicro.mds.qmw.ac.uk/∼mpallen

Table.

Quantity of paper flowing into general practices*

| Type of document | Quantity (per partner per working week) |

|---|---|

| Patient related | Up to 141 items |

| Profession related | Up to 44 items |

| Practice management related | Up to 18 items |

| “Junk mail” | Up to 2 kg |

Data from NHS Executive (1995)6

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Department of Health. The new NHS: modern, dependable. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Management Executive. Information management and technology strategy: overview. London: Information Management Group, NHSME; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. The national health service: a service with ambitions. London: DoH; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Executive. Seeing the wood, sparing the trees. Leeds: NHS Executive; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson R. NHS-wide networking and patient confidentiality. BMJ. 1995;311:5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Executive. Patients, not paper. Leeds: NHS Executive; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee of Public Accounts. The hospital information support systems initiative. PAC 7th report, House of Commons (session 1996/97). London: Stationery Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonelli C. The economic theory of information networks. In: Antonelli C, editor. The economics of information networks. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson B, Keen J. Transaction costs, externalities and information technology in health care. Health Economics. 1996;5:25–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199601)5:1<25::AID-HEC181>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan F, Mitchell E. Has general practitioner computing made a difference to patient care? A systematic review of published reports. BMJ. 1995;311:848–852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston M, Langton K, Haynes B, Mathieu A. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on clinician performance and patient outcome. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:135–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-2-199401150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lock C. What value do computers provide to NHS hospitals? BMJ. 1996;312:1407–1410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Audit Commission. For your information. London, HMSO, 1995.

- 14.Committee of Public Accounts. Wessex Regional Health Authority regional information systems plan. PAC 63rd report, House of Commons (session 1992/93). London, HMSO, 1993.

- 15.National Audit Office. Department of Health: the hospital information support systems initiative. London, Stationery Office, 1996.

- 16.US Congress Office of Technology Assessment. Bringing health care online: the role of information technologies. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office; 1995. (OTA-ITC-624.) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besanko D, Dranove D, Shanley M. Economics of strategy. New York: Wiley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. Report on the review of patient-identifiable information. London: Department of Health; 1997. (Caldicott committee report). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Information Management Group of the NHS Management Executive. Investment appraisal and benefits realisation for IM&T. Vol 2. The approach. London: Department of Health, 1993.

- 20.Wyatt J. Hospital information management: the need for clinical leadership. BMJ. 1995;311:175–180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]