Most doctors are used to assessing the health needs of their individual patients. Through professional training and clinical experience we have developed a systematic approach to this assessment and we use it before we start a treatment that we believe to be effective. Such a systematic approach has often been missing when it comes to assessing the health needs of a local or practice population.

The health needs of individual patients coming through the consulting room door may not reflect the wider health needs of the community. If people have a health problem that they believe cannot be helped by the health service, then they will not attend. For example, many people with angina or multiple sclerosis are not known to either their local general practitioner or to a hospital specialist.1,2 Other groups of patients who may need health care but do not demand it include homeless people and people with chronic mental illness.

Distinguishing between individual needs and the wider needs of the community is important in the planning and provision of local health services. If these needs are ignored then there is a danger of a top-down approach to providing health services, which relies too heavily on what a few people perceive to be the needs of the population rather than what they actually are.

Summary points

Health needs assessment is the systematic approach to ensuring that the health service uses its resources to improve the health of the population in the most efficient way

It involves epidemiological, qualitative, and comparative methods to describe health problems of a population; identify inequalities in health and access to services; and determine priorities for the most effective use of resources

Health needs are those that can benefit from health care or from wider social and environmental changes

Successful health needs assessments require a practical understanding of what is involved, the time and resources necessary to undertake assessments, and sufficient integration of the results into planning and commissioning of local services

What is health needs assessment?

Health needs assessment is a new phrase to describe the development and refinement of well established approaches to understanding the needs of a local population. In the 19th century the first medical officers for health were responsible for assessing the needs of their local populations. More recently, in the 1970s the Resource Allocation Working Party assessed relative health needs on the basis of standardised mortality ratios and socioeconomic deprivation in different populations, and it used this formula to recommend fairer redistribution of health service resources.3 The 1992 Health of the Nation initiative was a government attempt to assess national health needs and determine priorities for improving health.4 Health needs assessment has come to mean an objective and valid method of tailoring health services—an evidence based approach to commissioning and planning health services.

Although health needs assessments have traditionally been undertaken by public health professionals looking at their local population, these local health needs should be paramount to all health professionals. Hospitals and primary care teams should both aim to develop services to match the needs of their local populations. Combining population needs assessment with personal knowledge of patients’ needs may help to meet this goal.5

Why has needs assessment become important?

The costs of health care are rising. Over the past 30 years expenditure on health care has risen much faster than the cost increases reported in other sectors of the economy, and health care is now one of the largest sectors in most developed countries.6 Medical advances and demographic changes will continue the upward pressure on costs.7

At the same time the resources available for health care are limited. Many people have inequitable access to adequate health care, and many governments are unable to provide such care universally. In addition there is a large variation in availability and use of health care by geographical area and point of provision.8 Availability tends to be inversely related to the need of the population served.9

Another force for change is consumerism. The expectations of members of the public have led to greater concerns about the quality of the services they receive—from access and equity to appropriateness and effectiveness.

These factors have triggered reforms of health services in both developed and developing countries. In Britain these reforms resulted in the separation of the responsibility for financing health care from its provision and in the establishment of a purchasing role for health authorities and general practitioners. Health authorities had greater opportunities to try to tailor local services to their own populations, and the 1990 National Health Service Act required health authorities to assess health needs of their populations and to use these assessments to set priorities to improve the health of their local population.10,11 This has been reinforced by more recent work on inequalities in health, suggesting that health authorities should undertake “equity audits” to determine if healthcare resources are being used in accordance with need.12

At a primary care level, through fundholding, locality commissioning, and total purchasing projects, general practitioners have become more central to strategic planning and development of health services. With this increased commissioning power has come the increased expectation from patients and politicians that decision making would reflect local and national priorities, promoting effective and equitable care on the basis of need.13 The Labour government has committed itself to ensuring access to treatment according to “need and need alone,” and the key functions of primary care groups will be to plan, commission, and monitor local health services to meet identified local needs.14,15

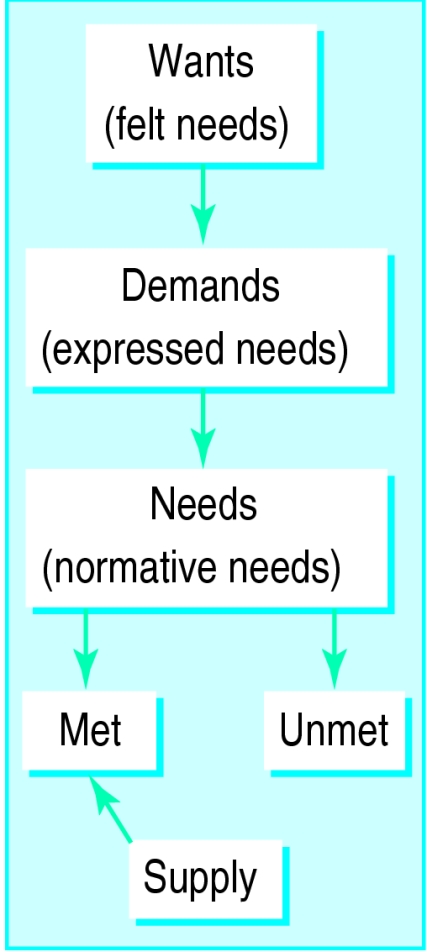

Needs

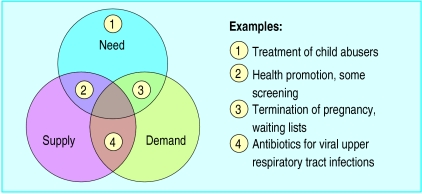

Doctors, sociologists, philosophers, and economists all have different views of what needs are.16–20 In recognition of the scarcity of resources available to meet these needs, health needs are often differentiated as needs, demands, and supply (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Different aspects of needs

Need

in health care is commonly defined as the capacity to benefit. If health needs are to be identified then an effective intervention should be available to meet these needs and improve health. There will be no benefit from an intervention that is not effective or if there are no resources available.

Demand

is what patients ask for; it is the needs that most doctors encounter. General practitioners have a key role as gatekeepers in controlling this demand, and waiting lists become a surrogate marker and an influence on this demand. Demand from patients for a service can depend on the characteristics of the patient or on the media’s interest in the service. Demand can also be induced by supply: geographical variation in hospital admission rates is explained more by the supply of hospital beds than by indicators of mortality21,22; referral rates of general practitioners owe more to the characteristics of individual doctors than to the health of their populations.23

Supply

is the health care provided. This will depend on the interests of health professionals, the priorities of politicians, and the amount of money available. National health technology assessment programmes have developed in recognition of the importance of assessing the supply of new services and treatments before their widespread introduction.

Need, demand, and supply overlap, and this relation is important to consider when assessing health needs (fig 2).20

Figure 2.

Relation between need, supply, and demand—central area shows ideal relation. Modified from Stevens and Raferty.24

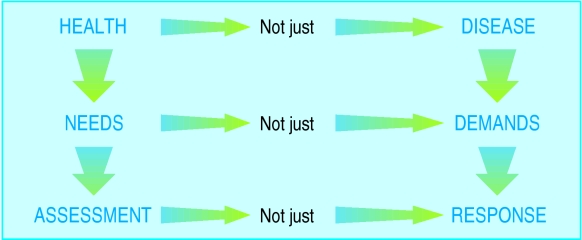

Health needs

The World Health Organisation’s definition of health is often used: “Health is a state of complete physical, psychological, and social wellbeing and not simply the absence of disease or infirmity.” A more romantic definition would be Freud’s: “Health is the ability to work and to love.”

Healthcare needs

are those that can benefit from health care (health education, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, terminal care). Most doctors will consider needs in terms of healthcare services that they can supply. Patients, however, may have a different view of what would make them healthier—for example, a job, a bus route to the hospital or health centre, or decent housing.

Health needs

incorporate the wider social and environmental determinants of health, such as deprivation, housing, diet, education, employment. This wider definition allows us to look beyond the confines of the medical model based on health services, to the wider influences on health (box). Health needs of a population will be constantly changing, and many will not be amenable to medical intervention.

Influences on health

Environment: housing, education, socioeconomic status, pollution

Behaviour: diet, smoking, exercise

Genes: inherited health potential

Health care: including primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention

Health needs assessment

Assessment of health needs is not simply a process of listening to patients or relying on personal experience. It is a systematic method of identifying unmet health and healthcare needs of a population and making changes to meet these unmet needs. It involves an epidemiological and qualitative approach to determining priorities which incorporates clinical and cost effectiveness and patients’ perspectives. This approach must balance clinical, ethical, and economic considerations of need—that is, what should be done, what can be done, and what can be afforded.25

Health needs assessment should not just be a method of measuring ill health, as this assumes that something can be done to tackle it. Incorporating the concept of a capacity to benefit introduces the importance of effectiveness of health interventions and attempts to make explicit what benefits are being pursued. Economists argue that the capacity to benefit is always going to be greater than available resources and that health needs assessment should also incorporate questions of priority setting,26 suggesting that many needs assessments are simply distractions from the difficult decisions of rationing.27

For individual practices and health professionals, health needs assessment provides the opportunity for:

Describing the patterns of disease in the local population and the differences from district, regional, or national disease patterns;

Learning more about the needs and priorities of their patients and the local population;

Highlighting the areas of unmet need and providing a clear set of objectives to work towards to meet these needs;

Deciding rationally how to use resources to improve their local population’s health in the most effective and efficient way;

Influencing policy, interagency collaboration, or research and development priorities.

Importantly, health needs assessment also provides a method of monitoring and promoting equity in the provision and use of health services and addressing inequalities in health.28,29

The importance of assessing health needs rather than reacting to health demands is widely recognised, and there are many examples of needs assessment in primary and secondary care.21,30,31

There is no easy, quick-fix recipe for health needs assessment. Different topics will require different approaches. These may involve a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods to collect original information, or adapting and transferring what is already known or available.

The stimulus for these assessments is often the personal interest of an individual or the availability of new funding for the development of health services. However, assessments should also be prompted by the importance of the health problem (in terms of frequency, impact, or cost), the occurrence of critical incidents (the death of a patient turned away because the intensive care unit is full), evidence of effectiveness of an intervention, or publication of new research findings about the burden of a disease.

Why do projects fail?

Some needs assessments have been more successful than others. Projects may fail for several reasons.31–33

Firstly, what is involved in assessing health needs and how it should be undertaken may not be understood. Educational strategies can improve the understanding and necessary skills of health professionals, and local public health teams can provide valuable support and guidance. Common sense can be a more important asset than detailed methodological understanding.34 Starting with a simple and well defined health topic can provide experience and encourage success.

Secondly, projects may fail because of a lack of time, resources, or commitment. The time and resources required can be small when shared among professionals in a team, and such sharing has the potential to be team building. Involving other organisations such as social services, local authorities, or voluntary groups can provide similar advantages and encourage multiagency working. Integration of needs assessment into audit and education can also provide better use of scarce time. Such investment of time and effort is likely to become increasingly necessary in order to justify extra resources.

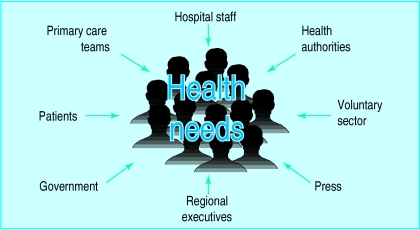

A third reason is the failure to integrate the results with planning and purchasing intentions to ensure change. The planning cycle should begin with the assessment of need.28 Objectives must be clearly defined (box) and relevant stakeholders or agencies—be they primary care teams, hospital staff, health authorities, the voluntary sector, the media, regional executives, government, or patients—must be involved appropriately (fig 3). Although such an assessment may produce a multitude of needs, criteria can be used to prioritise these needs—for example, the importance of a problem in terms of frequency or severity, the evidence of effectiveness of interventions, or the feasibility for change. Needs assessments that do not include sufficient attention to implementation will become little more than academic or public relations exercises.

Questions to ask when assessing health needs

What is the problem?

What is the size and nature of the problem?

What are the current services?

What do patients want?

What are the most appropriate and effective (clinical and cost) solutions?

What are the resource implications?

What are the outcomes to evaluate change and the criteria to audit success?

Figure 3.

Contributors to needs assessment

This series will describe the different approaches to assessing health needs, how to identify topics for health needs assessments, which practical approaches can be taken, and how the results can be used effectively to improve the health of local populations. It will give examples of needs assessment from primary care but will also cover the specific problems of needs assessment for hard to reach groups. Many of the techniques of community appraisals used in needs assessment originate from experience in developing countries, and some of the lessons from this experience will be described.

Figure.

These articles have been adapted from Health Needs Assessment in Practice, edited by John Wright, which will be published in July

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Bibby and Dee Kyle for their valuable contributions and to Margaret Haigh for secretarial support.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Smith R. Rationing: the search for sunlight. BMJ. 1991;303:1561–1562. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6817.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford HL, Gerry E, Airey CM, Johnson MH, Williams DRR. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Leeds District. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Department of Health and Social Security. Sharing resources for health in England: report of the Resource Allocation Working Party. London: HMSO; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. The Health of the Nation: a strategy for health in England. London: HMSO; 1992. (Cm 1986.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanks J, Kheraj S, Fish S. Better ways of assessing health needs in primary care. BMJ. 1995;310:480–481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6978.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health care systems in transition: the search for efficiency. Paris: OECD; 1990. (Social policy studies No 7.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison A, Dixon J, New B, Judge K. Funding the NHS. Can the NHS cope in future. BMJ. 1997;314:139–142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7074.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson TV, Mooney G. The challenge of medical practice variations. London: McMillan; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;i:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. Working for patients. London: HMSO; 1989. (Cm 555.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health Service Management Executive. Assessing health care needs. Leeds: NHSME; 1991. (DHA project discussion paper.) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Variations Subgroup of the Chief Medical Officer’s Health of the Nation Working Group. Variations in health. What can the Department of Health and the NHS do? London: Department of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Service Executive. An accountability framework for GP fundholding: towards a primary care led NHS. Leeds: NHSE; 1994. (EL(94)54.) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Secretary of State for Scotland. Designed to care. Edinburgh: Department of Home and Health, Scottish Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Executive. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culyer AJ. Need and the National Health Service. London: Martin Robertson; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradshaw J. A taxonomy of social need. In: McLachlan G, editor. Problems and progress in medical care. 7th series. London: Oxford University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankel S. Health needs, health-care requirements and the myth of infinite demand. Lancet. 1991;337:1588–1589. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93276-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams . Priorities not needs. In: Corden A, Robertson G, Tolley K, editors. Meeting needs. Aldershot: Avebury Gower; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens A, Gabbay J. Needs assessment needs assessment. Health Trends. 1991;23:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldstein MS. Effects of differences in hospital bed scarcity on type of use. BMJ. 1964;ii:562–565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5408.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkup B, Forster D. How will health needs be measured in districts? Implications of variations in hospital use. J Public Health Med. 1990;12:45–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkin D. Patterns of referral: explaining variation. In: Roland M, Coulter A, editors. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens A, Raferty J, editors. Health care needs assessment—the epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black D. A doctor looks at health economics. Office of Health Economics annual lecture. London: OHE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donaldson C, Mooney G. Needs assessment, priority setting, and contracts for health care: an economic view. BMJ. 1991;303:1529–1530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6816.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mooney G. Key issues in health economics. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Womersley J, McCauley D. Tailoring health services to the needs of individual communities. J Publ Health Med. 1987;41:190–195. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majeed FA, Chaturvedi N, Reading R, Ben-Shlomo Y. Monitoring and promoting equity in primary and secondary care. BMJ. 1994;308:1426–1429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6941.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillam SJ, Murray SA. Needs assessment in general practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1996. (Occasional paper 73.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan J, Wright J, Wilkinson J, Williams DRR. Health needs assessment in primary care: a study of the understanding and experience in three districts. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.London Health Economics Consortium. Local health and the vocal community, a review of developing practice in community based health needs assessment. London: London Primary Health Care Forum; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordan J, Wright J. Making sense of health needs assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;48:695–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillam S. Assessing the health care needs of populations—the general practitioner’s contribution [editorial] Br J Gen Pract. 1992;42:404–405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]