Abstract

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy which is associated with increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in exposed offspring. The pathophysiological mechanisms mediating this relationship are currently unknown, and one potential candidate is the anti-angiogenic factor soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), which is highly elevated in PE. While sFlt-1 can impair angiogenesis via inhibition of VEGFA signalling, it is unclear whether it can directly affect neuronal development independently of its effects on the vasculature. To test this hypothesis, the current study differentiated the human neural progenitor cell (NPC) line ReNcell® VM into a mixed culture of mature neurons and glia, and exposed them to sFlt-1 during development. Outcomes measured were neurite growth, cytotoxicity, mRNA expression of nestin, MBP, GFAP, and βIII-tubulin, and neurosphere differentiation. sFlt-1 induced a significant reduction in neurite growth and this effect was timing- and dose-dependent up to 100 ng/ml, with no effect on cytotoxicity. sFlt-1 (100 ng/ml) also reduced βIII-tubulin mRNA and neuronal differentiation of neurospheres. Undifferentiated NPCs and mature neurons/glia expressed VEGFA and VEGFR-2, required for endogenous autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling, while sFlt-1 treatment prevented the neurogenic effects of exogenous VEGFA. Overall, these data provide the first experimental evidence for a direct effect of sFlt-1 on neurite growth and neuronal differentiation in human neurons through inhibition of VEGFA signalling, clarifying our understanding of the potential role of sFlt-1 as a mechanism by which PE can affect neuronal development.

Keywords: axon, differentiation, growth, Neuron, Pre-eclampsia, sFLT-1

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a commonly occurring hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (HDP) which affects approximately 5% of first-time pregnancies, and is characterised by new-onset hypertension on or after 20 weeks’ gestation and one or more of proteinuria, organ dysfunction or uteroplacental dysfunction [1,2]. While PE has long been known to predispose the mother towards long-term morbidity, it is now recognised to have deleterious consequences for the long-term health outcomes of the offspring [3,4]. Of particular interest, PE exposure increases the risk of diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and intellectual disability (ID) [5–8]. In line with this, children who are prenatally exposed to PE exhibit neuroanatomical alterations [9,10], and offspring from animal models of PE exhibit various brain and behavioural deficits [11–13]. PE exposure is, therefore, likely to influence neurodevelopmental processes in the foetal brain such as differentiation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) into neurons, or neurite growth, both of which have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders [14,15]. Currently, however, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which PE affects neuronal development are yet to be elucidated.

PE involves various pathophysiological pathways that could each be responsible for the effects on foetal neurodevelopment – these include maternal immune activation [16], oxidative stress [17,18], and altered placental secretion of neurotrophic factors [19]. Overall, however, there is a lack of direct experimental evidence for the molecular mediators involved. Arguably the most well described molecular alteration in PE is an increase in the anti-angiogenic factor soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), also known as soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sVEGFR-1) [20–22]. Elevated sFlt-1 circulates in PE and contributes to endothelial cell dysfunction and disease progression, and is so well characterised that the elevated sFlt-1 and corresponding decrease in pro-angiogenic placental growth factor (PlGF) is being used clinically as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of PE [23,24]. Furthermore, overexpression of human sFlt-1 is used as a pre-clinical animal model of PE, and knockdown of sFlt-1 reduces the features of PE in a baboon PE model [25,26].

Importantly, sFlt-1 is elevated in the umbilical cord blood of PE-exposed infants, and therefore may be increased in the developing foetal brain [21,27,28]. It has been hypothesised that the imbalance in angiogenic factors in PE, including elevated sFlt-1 and reduced PlGF, could impair the normal development of the cerebrovasculature [29], and there is in fact evidence of abnormal cerebral blood vessel development in children prenatally exposed to PE [10]. It is less well known, however, whether elevated sFlt-1 can directly affects neuronal development. sFlt-1 circulates freely and binds the angiogenic factor VEGFA with high affinity, sequestering it to prevent pro-angiogenic signalling through the transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, VEGFR-2 [30,31]. The trophic effects of VEGFA are not confined to the vasculature; however, it also exerts a neurotrophic effect on developing neurons. Animal studies have demonstrated a neurogenic role for VEGFA in vivo [32–34]. Although the study by Okabe [2020] observed the effects of conditional VEGFA knockout on the brain were through indirect effects on cerebral blood vessel development, several studies have shown a potent and direct neurogenic effect of VEGFA in neuronal culture systems devoid of endothelial cells, whereby it promotes neural progenitor cell proliferation, neurite growth, MAP-2 and βIII Tubulin expression, and activation of neurogenic signalling pathways [32,33,35–37]. Neurons do not rely exclusively on exogenous VEGFA, but synthesise their own de novo, and express the VEGFR-2 receptor to mediate downstream signalling [32,33,36]. This is highly suggestive that, independently of the vasculature, neurons can engage in neurogenic autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling, which may therefore be affected by elevated levels of s-Flt1.

In support of this, a recent transgenic mouse study reported that fetoplacental sFlt-1 overexpression alters neuronal cell density in the cortex and caudate putamen of the offspring, and reduces cerebral Map2 and Ngf expression [25]. Another pair of studies conditionally overexpressed sFlt-1 in the brain of adult mice, and examined the two adult neural stem cell niches, the subventricular zone and subgranular zone. Local sFlt-1 overexpression impaired the development and maturation of adult newly-born olfactory interneurons, but not hippocampal neurons [38,39]. This raises the possibility that different subpopulations of neurons differ in their responsiveness to sFlt-1, and it is unclear how much of the in vivo effect is indirect, via paracrine signalling through other cells such as ependymal or microglial cells. To date, only two studies have examined a direct effect of sFlt-1 in neurons, whereby sFlt-1 reduced NPC proliferation and increased apoptosis [32,37], although in the 20 years since their publication, it has not been shown whether sFlt-1 directly affects neurogenesis or neuronal morphology. Furthermore, the entire literature on VEGFA and sFlt-1 in vitro and in vivo is confined to rodent neurons, and thus it is currently unclear to what extent a potential anti-neurogenic effect of sFlt-1 might be conserved in humans, owing to species differences in gene expression profiles, electrophysiology, and developmental rates [40,41]. The current study sought to test the hypothesis that exogenous sFlt-1 exerts anti-neurogenic, and neurite growth inhibitory effects in developing human neurons; and, secondly, that these effects are mediated through inhibition of endogenous VEGFA signalling.

Materials and methods

Monolayer cell culture and treatments

Human neural progenitor ReNcell® VM cells (Sigma Aldrich) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM)/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham’s medium without antibiotics, supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 U/ml heparin, 2% (v/v) B-27, 1% (v/v) N-2, and 20 ng/ml EGF and 20 ng/ml FGF-2, and maintained in a T75 culture flask (Sarstedt) at 37°C and 5% CO2. B-27 and N-2 from ThermoFisher, FGF-2 from Peprotech, all other reagents from Sigma Aldrich. Media was changed every 2 days and when 80% confluent, cells were passaged and seeded at 12,500 cells per well in a laminin-coated 48-well plate for immunocytochemistry, or at 1 × 106 cells per well in a laminin-coated 6-well plate for RNA extraction. Twenty-four hours after plating, cells were washed with HBSS, and fresh media was added without EGF and FGF-2 to initiate differentiation [42]. Cells were differentiated for 15 days in vitro (DIV), and a complete media change was performed every 3 days.

For all experiments, treatments were given after each media change beginning on day 1 of differentiation, and analyses were performed 72 h after the last treatment. Final concentrations used were 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 (Abcam), and 50 ng/ml VEGFA (Peprotech). Sterile PBS was used in all experiments as a vehicle control.

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM)/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham’s medium, supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 10% FBS (all from Sigma Aldrich), and maintained in a T75 culture flask (Sarstedt) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Media was changed every 3 days and when 80% confluent, cells were passaged and seeded at 25,000 cells per well in a 24-well plate. Twenty-four hours after plating, treatments began. Cells were treated daily with 10 μM retinoic acid (RA, Sigma Aldrich) for 3 days to induce partial neuronal differentiation, concomitant with sFlt-1 treatment, and analyses were performed 72 h after first treatment.

Neurosphere cell culture

For neurosphere culture, ReNcell® VM underwent 7 days of proliferation followed by 4 days of differentiation. During the proliferation phase, 106 cells were cultured in suspension in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DMEM)/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham’s medium without antibiotics, supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 U/ml heparin, 2% B-27, 1% N-2, and 20 ng/mL EGF and FGF2 in an uncoated T25 flask (Sarstedt) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 with shaking. Cells were treated daily with 20 ng/ml EGF and FGF2 to prevent spontaneous differentiation, and on day 4 given a partial media change and treatment. Neurospheres were imaged by phase contrast microscopy at 4 DIV and 7 DIV to measure neurosphere diameter during proliferation stage.

Equal numbers of neurospheres were seeded onto laminin-coated 12-well plates in media without EGF or FGF2 to initiate differentiation. During this stage, cells migrate rapidly from the core of the sphere, grow extensive neurites, and differentiate into neurons and glia. Two alternative experiments were conducted, with cells exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 either for the full 11 days (treatment on days 1 and 4 of proliferation and day 1 of differentiation), or for the 4-day differentiation stage only (treatment on day 1 of differentiation). In both cases, analyses were performed at DIV 11 (7 days proliferation and 4 days differentiation).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was assessed using the CyQUANT™ LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Invitrogen). The LDH assay is a colorimetric method which measures extracellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity to determine cytotoxic cell damage. As per manufacturer’s guidelines, culture media from each experiment was collected and centrifuged to remove any remaining cells or debris, and the supernatant was retained and used for the assay. Approximately 50 μl of the medium was combined with 50 μl of the reaction mixture in a flat-bottomed, 96-well plate and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in darkness. Approximately 50 μl of stop solution was used to terminate the reaction, and absorbance was measured at 680 nm and subtracted from absorbance at 490 nm.

Immunocytochemistry

Monolayer and neurosphere cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at experimental endpoint and preserved in 10 mM PBS with 0.02% -Triton-X (PBS-T). Cells were incubated in 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 h to block non- specific binding and incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary antibody against βIII tubulin (1:1000, R&D Systems MAB1195). After overnight incubation, cells were washed in PBS-T and incubated at room temperature for 2 h with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen A11001). Cells were then re-blocked and stained overnight with a primary antibody against GFAP (1:1000, Abcam ab68428), followed by 2 h goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibody (1:500, Invitrogen A11012). Cells were washed in PBS-T, counterstained with DAPI, and imaged by fluorescence microscopy.

Microscopy and image analysis

All cells were imaged at ×20 magnification on an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope with a DP72 camera. SH-SY5Y cells and neurospheres at DIV 4 and DIV 7 were imaged live under phase contrast light microscopy; immunostained ReNcell® VM cells were imaged by fluorescence microscopy with FITC, DAPI and TXRED filters. Five non-overlapping fields were acquired per well and analyzed using ImageJ. Neurites were traced to calculate neurite length; in the case of ReNcell® VM cells, neurites were measured only in cells which were βIII tubulin+ and GFAP-. For positivity analysis, composite images were created, and a sample field of view was counted for cells which were βIII tubulin+/GFAP-, βIII tubulin-/GFAP+, βIII tubulin+/GFAP+, or βIII tubulin-/GFAP-. All experiments were performed in a blinded fashion.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted from confluent monolayers of ReNcell® VM using QIAzol lysis reagent and RNeasy Plus Universal RNA Isolation kit (Qiagen) as per manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA was then quantified by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher) and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Āpproximately 500 ng RNA per sample was used to synthesise complementary DNA (cDNA) using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher) as per manufacturer’s guidelines. cDNA was stored at 4°C until further use.

mRNA expression was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Single-gene reaction mixtures were made as per manufacturer’s instructions using cDNA samples, RNase-free water, 2X TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix (ThermoFisher), and 20X TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (ThermoFisher). The following FAM™-labelled probes were used: β2 Microglobulin (B2M) (Hs00187842_m1), Nestin (Hs04187831_g1), βIII tubulin (Hs00801390_s1), GFAP (Hs00909233_m1), Meylin Basic Protein (MBP) (Hs00921945_m1), VEGFA (Hs00900055_m1), VEGFR-1/sFlt-1 (Hs01052961_m1), and VEGFR-2 (Hs00911700_m1). cDNA was amplified for 40 cycles using the Light Cycler 480 thermocycler (Roche). The cycle threshold (Ct) for detection of fluorescent signal of each gene was normalised to that of B2M as an endogenous control and used to calculate the delta-delta (dd) Ct, expressed as the relative change in expression compared with the control group mean.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 9. Statistical significance (α) was set at P<0.05, and the statistical tests applied to the data were one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test, Student’s paired two-tailed t-test, and two-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test. All data are expressed as the mean with standard error of the mean (SEM) where indicated.

Results

sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth in RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and human NPC-derived neurons

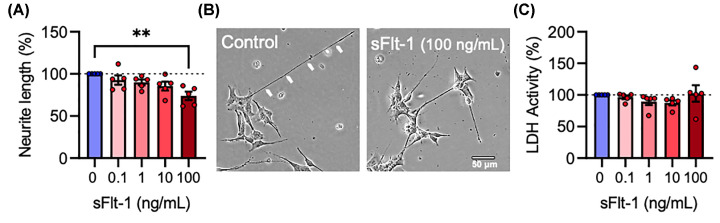

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were differentiated with RA and exposed to 0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 daily for 3 days to determine whether sFlt-1 affected neurite growth or cytotoxicity. sFlt-1 elicited a dose-dependent reduction in neurite growth (F4,20 = 5.042, P<0.01), which was statistically significant only at the highest concentration of 100 ng/ml (P<0.01) with a 25% reduction in neurite length (Figure 1A,B). sFlt-1 had no cytotoxic effect at any concentration tested (F4,20 = 0.9528, P=0.455) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth in RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells.

RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 or PBS as vehicle control, daily for 72 h. (A) Graph and (B) representative photomicrographs of neurite length. (C) Graph of extracellular LDH activity as a measure of cytotoxicity. Data are mean + SEM from five independent experiments (n=5) expressed as percentage of the control. One-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett’s test (**P<0.01 vs. control).

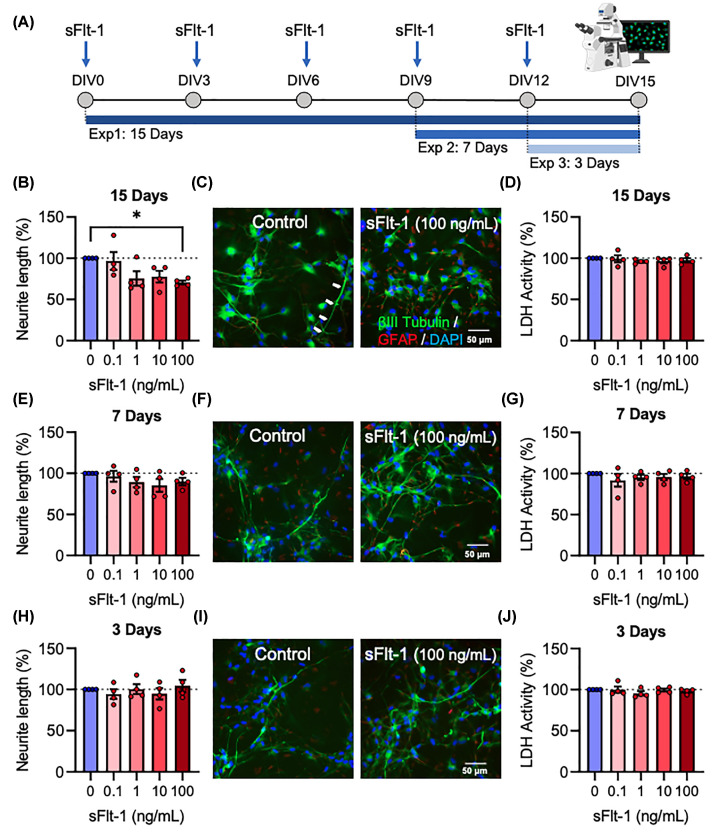

To determine whether this phenotype was present in mature human neurons, the dose response experiment was repeated in ReNcell® VM neural progenitor cells as they differentiated over 15 days into a mixed culture of neurons and glia. Three alternative experiments were conducted, with cells exposed to sFlt-1 for the full 15 days’ differentiation, the last 7 days, or the last 3 days only (Figure 2A). When exposed for the full 15 days’ differentiation, sFlt-1 reduced neurite growth (F4,15 = 3.57, P<0.05), which was only statistically significant at 100 ng/ml (P<0.05) (Figure 2B,C) with a 30% reduction in neurite length, recapitulating the inhibition of neurite growth observed in SH-SY5Y cells. When exposed only for the last 7 days, however, the reduction was not statistically significant (F4,15 = 1.082, P=0.4) (Figure 2E,F), and when exposed only for the last 3 days, there was no observable effect at all (F4,15 = 0.5025, P=0.735) (Figure 2H,I). sFlt-1 was not cytotoxic at any concentration after 15 (F4,15 = 0.4607, P=0.764), 7 (F4,15 = 0.4624, P=0.762), or 3 (F4,15 = 0.7331, P=0.583) days’ exposure (Figure 2D,G,J). Taken together, these data provide evidence that sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth in developing human neurons, but only at long-term exposure, without any accompanying toxic effects on the cells.

Figure 2. sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth in human NPC-derived neurons.

ReNcell® VM were differentiated from human neural progenitor cells into neurons and glia over 15 days while exposed to 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 ng/ml sFlt-1, or PBS as vehicle control. (A) Timeline of cell treatments: all cells received a media change every 72 h for 15 days, followed by treatment with relevant concentration of sFlt-1. Three alternative experiments were conducted, with cells exposed to sFlt-1 for the full 15 days’ differentiation, the last 7 days, or the last 3 days. (B,C) Graph and representative photomicrographs of neurite length and (D) cytotoxicity in cells treated with sFlt-1 for 15 days. (E,F) Graph and representative photomicrographs of neurite length and (G) cytotoxicity in cells treated with sFlt-1 for 7 days. (H,I) Graph and representative photomicrographs of neurite length and (J) cytotoxicity in cells treated with sFlt-1 for 3 days. Data are mean + SEM from four independent experiments (n=4) expressed as percentage of the control. One-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett’s test (*P<0.05 vs. control); DIV = days in vitro.

sFlt-1 reduces neuronal differentiation of human NPCs

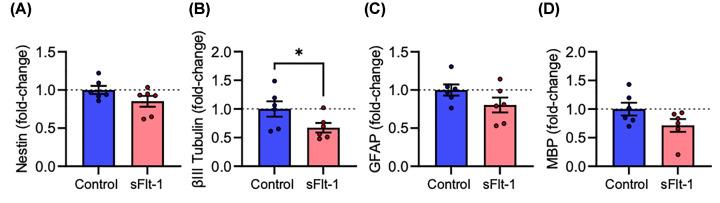

ReNcell® VM neural progenitor cells were treated with 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 during 15 days’ differentiation into neurons and glia, and RNA was extracted to assess gene expression by RT-qPCR. sFlt-1 did not affect expression of Nestin mRNA (t5 = 1.423, P=0.214), a common marker for neural progenitor cells (Figure 3A). sFlt-1-treated cells expressed lower levels of βIII-tubulin mRNA (t5 = 2.907, P<0.05), a neuronal cytoskeletal protein (Figure 3B), but not the glial markers GFAP (t5 = 1.343, P=0.237) (Figure 3C) or MBP (t5 = 1.698, P=0.1502) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. sFlt-1 reduces βIII tubulin mRNA expression in human NPC-derived neurons.

ReNcell® VM were differentiated into neurons and glia over 15 days while exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 or PBS as vehicle control. On day 15, RNA was extracted, and relative mRNA expression measured by RT-qPCR. Graphs of (A) Nestin, (B) βIII Tubulin, (C) GFAP, and (D) MBP mRNA expression. Data are mean + SEM from six independent experiments (n=6) expressed as fold-change of the control group mean. Student’s paired t-test (*P<0.05 vs. control).

To determine whether this reduction in βIII-tubulin mRNA expression is reflected at the protein level, ReNcell® VM were grown as neurospheres, which involved a 7-day proliferation and a 4-day differentiation stage, and immunostained for βIII-tubulin and GFAP. Neurospheres were exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 either for both stages, or for the proliferation or differentiation stages only (Figure 4A). Exposure to sFlt-1 during proliferation did not affect neurosphere diameter at 4 DIV (t3 = 1.590, P=0.21) or 7DIV (t3 = 0.761, P=0.502) (Figure 4B–D). However, sFlt-1 did decrease neuronal differentiation. Exposure for the full 11 days reduced the proportion of cells which expressed βIII-tubulin but not GFAP (t3 = 4.527, P<0.05), representing mostly mature neurons which no longer express GFAP. There was a correspondingly small but statistically non-significant increase in cells expressing GFAP but not βIII-tubulin (t3 = 2.336, P=0.102), and no difference in the number of cells expressing both βIII-tubulin and GFAP (t3 = 0.9217, P=0.425), or those expressing neither protein (t3 = 1.136, P=0.338) (Figure 4E,F). Exposure to sFlt-1 for only the 4-day differentiation stage was sufficient to produce this phenotype, reducing the number of βIII-tubulin+/GFAP- cells (t3 = 5.577, P<0.05), but not the number of βIII-tubulin-/GFAP+ (t3 = 0.8843, P=0.443), βIII-tubulin+/GFAP+ (t3 = 0.4369, P=0.692), or βIII-tubulin-/GFAP- (t3 = 1.038, P=0.378) cells (Figure 4G,H). Lastly, sFlt-1 treatment reduced neurite length from the neurospheres if added during both stages (t3 = 4.003, P<0.05) or only the proliferation stage (t3 = 3.2984, P<0.05), but not if added only during the differentiation stage (t3 = 0.34519, P=0.753), which is somewhat in line with the previous finding in monolayer cultures whereby sFlt-1 reduced neurite growth only if it was present from the beginning of the experiment. Overall, these findings demonstrate that exposure of developing human neurons to sFlt-1 reduces their βIII-tubulin mRNA expression, and the proportion of cells which express βIII-tubulin protein but not GFAP, suggesting an anti-neurogenic role for sFlt-1.

Figure 4. sFlt-1 reduces neuronal differentiation of human neurospheres.

ReNcell® VM were grown into neurospheres and exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 or PBS as vehicle control. (A) Timeline of cell treatments: neurospheres were cultured in suspension with neural progenitors kept in a proliferative state for 7 days, followed by differentiation for 4 days. Two alternative experiments were conducted, with cells exposed to sFlt-1 either for the full 11 days, or for the 4-day differentiation stage only. (B,C) Neurosphere diameter at 4DIV and 7DIV, and (D) representative photomicrographs at 7DIV. (E,F) Graph and representative photomicrographs of βIII Tubulin and GFAP protein expression in cells treated for both proliferation and differentiation stages. (G,H) Graph and representative photomicrographs of βIII Tubulin and GFAP protein expression in cells treated for differentiation stage only. Data are mean + SEM from four independent experiments (n=4) expressed as percentage of positive cells. Student’s paired t-test (*P<0.05 vs. control).

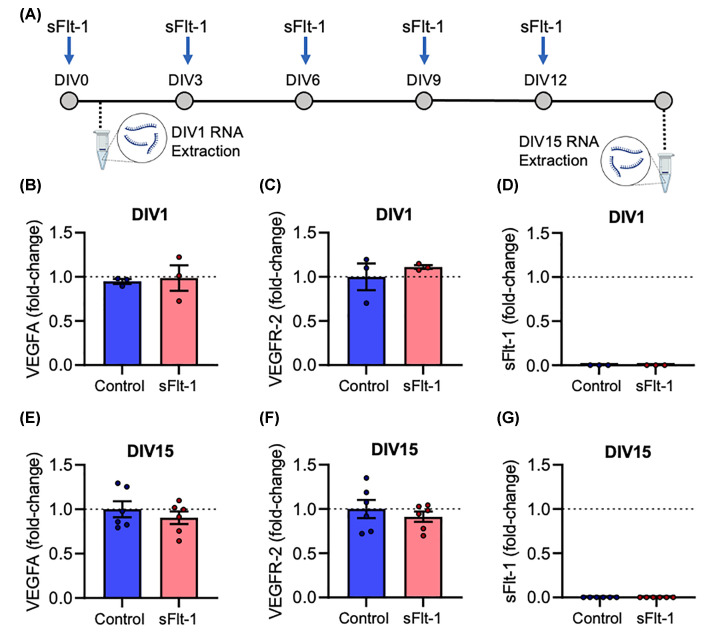

ReNcell VM express machinery for endogenous VEGFA autocrine and paracrine signalling, which is unchanged by sFlt-1 treatment

sFlt-1 is known to act as a decoy receptor to VEGFA; however, there is no VEGFA in the media used in the present study. We, therefore, tested the hypothesis that ReNcell® VM express endogenous VEGFA and the VEGFR-2 receptor required for autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling, as a potential mechanism by which sFlt-1 could exert its anti-neurogenic effects. RNA was extracted from both undifferentiated NPCs (DIV 1) and mature neurons and glia (DIV 15) (Figure 5A). At DIV1, NPCs express both VEGFA and VEGFR-2 mRNA, and the relative expression of both genes was unaffected by sFlt-1 treatment (VEGFA, t2 = 0.2296, P=0.84; VEGFR-2, t2 = 0.7554, P=0.529) (Figure 5B,C). The expression of both genes was sustained at DIV15 after neuronal differentiation, and was unchanged by sFlt-1 (VEGFA, t5 = 0.6177, P=0.564; VEGFR-2, t5 = 0.5996, P=0.575) (Figure 5E,F). Therefore, both undifferentiated human NPCs, and differentiated human neurons and glia, express both the ligand and receptor for autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling. Importantly, no VEGFR-1/sFlt-1 mRNA could be detected at either stage (Figure 5D,G), indicating there is no endogenous inhibition of VEGFA signalling via sFlt-1 under these experimental conditions.

Figure 5. ReNcell VM express machinery for endogenous VEGFA autocrine and paracrine signalling, which is unchanged by sFlt-1 treatment.

ReNcell® VM were differentiated into neurons and glia over 15 days while exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1, or PBS as vehicle control. (A) Timeline of experiment: on day 1 (undifferentiated) and day 15 (differentiated), RNA was extracted, and relative mRNA expression measured by RT-qPCR. (B–D) Graphs of (B) VEGFA, (C) VEGFR-2, and (D) sFlt-1/VEGFR-1 mRNA expression at DIV1. (E–G) Graphs of (E) VEGFA, (F) VEGFR-2, and (G) sFlt-1/VEGFR-1 mRNA expression at DIV15. Data are mean + SEM from three independent experiments (n=3) expressed as fold-change of the control group mean. Student’s paired t-test.

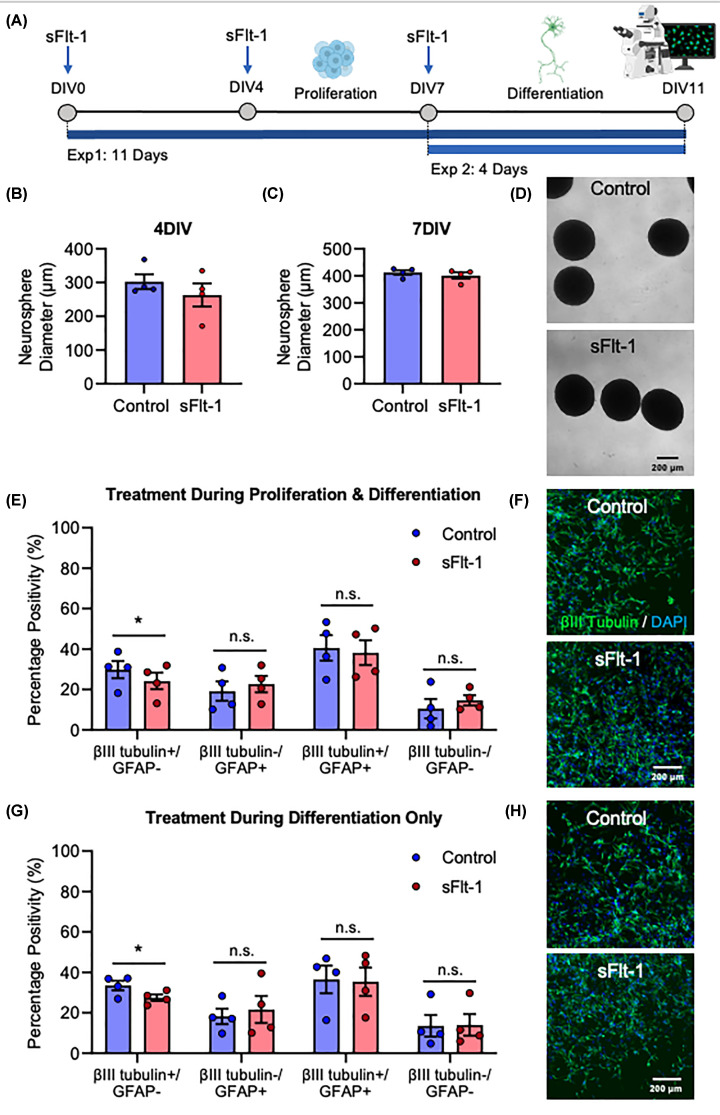

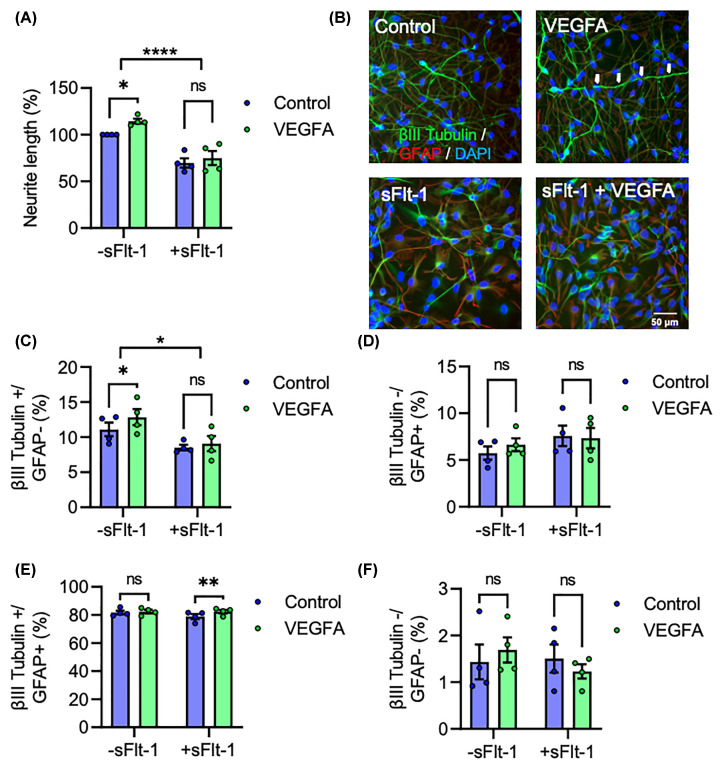

VEGFA exerts neurogenic effects only in the absence of sFlt-1

To determine if sFlt-1 inhibits the neurogenic effects of VEGFA in vitro, ReNcell® VM were treated with VEGFA, with or without sFlt-1 co-treatment, for 15 days’ differentiation. VEGFA increased neurite growth, but not in the presence of sFlt-1. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of sFlt-1 in reducing neurite growth (F1,12 = 56.58, P<0.0001), while post-hoc analysis revealed a significant increase with VEGFA treatment, only in the absence of sFlt-1 (P<0.05) (Figure 6A,B). In line with this increase in neurite length, VEGFA also promoted neuronal differentiation only in the absence of sFlt-1–sFlt-1 reduced the overall proportion of cells expressing βIII-tubulin but not GFAP after 15 days (F1,3 = 10.14, P<0.05), which was increased by VEGFA (P<0.05) only when sFlt-1 was not present (Figure 6B,C). Neither sFlt-1 nor VEGFA affected the number of βIII-tubulin-/GFAP+ (Figure 6D) or Tubulin-/GFAP- (Figure 6F) cells, although VEGFA did lead to a small increase the number of cells expressing both proteins (F1,3 = 12.58, P<0.05), specifically in the presence of sFlt-1 (P<0.05) (Figure 6E). Overall, these data are strongly in line with the neurite length and differentiation data presented above, and demonstrate that while VEGFA promotes neurite growth and neurogenesis, it is unable to do so in the presence of sFlt-1.

Figure 6. VEGFA exerts neurogenic effects only in the absence of sFlt-1.

ReNcell® VM were differentiated into neurons and glia over 15 days while exposed to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1, 50 ng/ml VEGFA, both sFlt-1 and VEGFA, or PBS as vehicle control. (A,B) Graph and representative photomicrographs of neurite length. (C–F) Graphs of βIII Tubulin and GFAP protein expression. Data are mean + SEM from four independent experiments (n=4) expressed as percentage of control for (A) or as percentage positive cells for (C–F). Two-way ANOVA and post-hoc Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. control).

Discussion

Exposure to PE increases the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in exposed offspring, suggesting that PE may impact neurodevelopmental processes in the foetal brain, although the molecular mediators are largely unknown. As PE is characterised by elevated sFlt-1, here we tested the hypothesis that sFlt-1 may have a direct anti-neurogenic role on developing human neurons. In support of this proposal, we found that exposure to 100 ng/ml sFlt-1 during differentiation led to a ∼25–30% reduction in neurite length in both SH-SY5Y cells and ReNcell® VM-derived neurons. Interestingly, the effect was also timing-dependent, in that exposure to sFlt-1 was required from the beginning of the 15-day differentiation process to elicit an effect, thus demonstrating that sFlt-1 inhibits the growth, but not the maintenance of established neurites. This notion is supported by the finding that sFlt-1 reduces neurite length of neurospheres, but only if it is present in the culture medium from the beginning of the experiment, and further by the findings of Licht et al. (2010) who report that sFlt-1 overexpression in mice impairs dendrite growth and spine number in newly born, but not mature adult olfactory neurons, and is mechanistically plausible given that the initial growth and retraction of neurites can be governed by different processes [43]. Interestingly, in the case of neurospheres in the current study, early treatment with sFlt-1 reduced neurite length even after it was removed at the beginning of differentiation, implying that neurite growth mechanisms do not recover after this early exposure, although a longer experiment would be required to discern if this is indeed the case. These findings are in line with the putative mechanisms of VEGFA inhibition, given that VEGFA increases neurite length in vitro [35,36]. Although the concentration of 100 ng/ml is close to physiological amniotic fluid concentrations in PE [21], physiological cord blood concentrations, while highly elevated in PE compared with uncomplicated pregnancy, are reported as 0.25–5 ng/ml [21,31,44,45]. While an equivalent dose of 1 ng/ml did reduce neurite length in our study by ∼25%, this was not statistically significant (P=0.08), and all further experiments used a single concentration of 100 ng/ml.

sFlt-1 did not affect neurosphere size, which appears contradictory to reports that VEGFA increases NPC proliferation, while sFlt-1 decreases proliferation [32,46]. However, neurosphere size alone is not equivalent to proliferation, which is governed by additional factors such as the number and viability of spheres. In fact, after 3–4 DIV, sphere size becomes negatively correlated with the number of viable cells [47]. On the other hand, sFlt-1 significantly reduced the expression of transcripts for βIII-tubulin, without any significant effect on nestin, or glial markers GFAP or MBP. Human neurons and glia co-express βIII-tubulin and GFAP at intermediate and immature stages of differentiation [48,49], and they remain co-expressed by many cells in differentiated cultures [50,51]. Therefore, restricting neurite length and neurogenesis measurements to βIII-tubulin+/GFAP- cells in the current study ensured only mature neurons which have survived this intermediate stage and no longer expressed GFAP were quantified. sFlt-1 reduced the proportion of cells in differentiated neurospheres expressing βIII-tubulin but not GFAP, indicating sFlt-1 inhibits neuronal differentiation. As with the reduction in neurite length, this decrease in neuronal differentiation is highly concordant with a hypothesised mechanism of VEGFA inhibition, with previous reports demonstrating a pro-neurogenic effect of exogenous VEGFA [35,37].

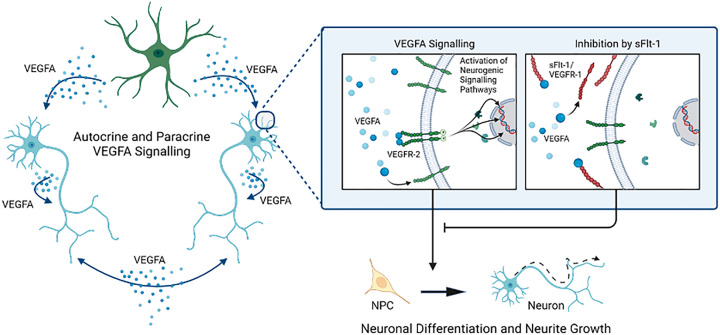

Both undifferentiated NPCs and differentiated neurons and glia express high levels of VEGFA and VEGFR-2 mRNA, the ligand and receptor pair required for autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling. Considering VEGFA is not a constituent of the culture media used in this study, any VEGFA found in the culture must be synthesised de novo, providing the first human neuron corroboration of the finding that rodent neurons engage in autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling independently of endothelial cells [35,37]. Importantly, Flt-1/VEGFR-1 mRNA was not detectable at either DIV1 or DIV 15, and therefore the only sFlt-1 present was that added exogenously. This is consistent with previous evidence that while rat hippocampal NPCs and cortical neurons express VEGFA and VEGFR-2, neither cell type expresses VEGFR-1 [32,36]. Finally, while VEGFA is known to elicit a pro-neurogenic effect on developing neurons, we observed that this is absent in the presence of sFlt-1. Given these data, we postulate that exogenous sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth and neurogenesis in human neurons via inhibition of endogenous neurogenic autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Summary of findings and proposed mechanism.

sFlt-1/VEGFR-1 reduces neurite growth and neuronal differentiation in human neural progenitor cells, whereas VEGFA increases neurite length and neuronal differentiation, but only in the absence of sFlt-1. ReNcell® VM express VEGFA and VEGFR-2, which modulate autocrine and paracrine VEGFA signalling, both as undifferentiated neural progenitors and as a mixed culture of neurons and glia. Crucially, there is no expression of sFlt-1 mRNA for endogenous inhibition of VEGFA signalling. Therefore, exogenous sFlt-1 is likely eliciting its anti-neurogenic effects by binding VEGFA and inhibiting endogenous VEGFA signalling.

While the present findings have implications for our understanding of the relationship between PE and neuron development, it is important to consider them within their in vivo context, which is markedly more complex. The most conspicuous feature that distinguishes the in vitro from the in vivo context is the influence of the cerebrovasculature. The anti-angiogenic role of sFlt-1 is well-described, and if insufficient vascular development results in local hypoxia, this can up-regulate neuronal VEGFA expression [52]. Furthermore, not only does vascular-derived VEGFA promote neurogenesis, but the relationship is reciprocal, in that neuron-derived VEGFA promotes local blood vessel formation via angiogenesis [34,37]. Secondly, there is the varying involvement of different cell types. Licht (2010) and Okabe (2020) report that VEGFR-2 is not highly expressed by mouse olfactory, hippocampal, or cortical neurons, but is instead expressed by local endothelial and ependymal cells, raising the possibility of indirect paracrine signalling through these other cell types. VEGFA also regulates glial development, by promoting oligodendrocyte precursor cell migration and astrocyte proliferation [46,53]. Additionally, certain subpopulations of adult neurons express transmembrane VEGFR-1, which can transduce signals in certain situations, such as sensory neurons in the context of neuropathic pain [54,55]. Thirdly, elevated sFlt-1 in PE cannot be seen as independent from other aspects of the disorder, most prominently maternal immune activation. Astrocytes and monocytes both increase sFlt-1 expression in response to cytokine stimulation [56,57], while sFlt-1 in turn modulates cytokine expression [58,59] and chemotactic migration of peripheral monocytes and microglia [60,61]. Therefore, local and peripheral immune cells are likely to exacerbate the anti-angiogenic and anti-neurogenic roles of sFlt-1, adding to the complexity of the in vivo environment. Lastly, it is important to consider that PE is generally diagnosed after 20 weeks’ gestation, when neuronal differentiation (and, to a lesser degree, neurite growth), is mostly already established in humans. Interestingly, sFlt-1 is in fact elevated in the first trimester of mothers who are only later diagnosed with PE [62], when neuronal differentiation and neurite growth are highly dynamic, although the difference in concentration is notably less than that in late pregnancy, and it is unclear whether this smaller difference in the first trimester is sufficient to elicit the single-cell effects reported in the current study. These factors should be considered when interpreting the effects of sFlt-1 in neurons.

The current study presents the first direct evidence that exogenous sFlt-1 reduces neurite growth and neurogenesis in human neurons. A significant strength of this work is the use of human NPCs and their differentiation into mature human neurons and glia. Further strengths include the concordance of different observations – neurite length findings were replicated in SH-SY5Y and ReNcell® VM; reduction in βIII-tubulin mRNA was confirmed by immunostaining; and the putative mechanism of VEGFA signalling is supported by VEGFA and VEGFR-2, but not VEGFR-1, mRNA expression at DIV1 and DIV15, and by sFlt-1 blocking the neurogenic effects of exogenous VEGFA. Nonetheless, there are some important limitations to this work. While the current study aimed to characterise the effects of sFlt-1 at a single cell level, the interpretation of these findings must take into account the increasingly complicated situation in vivo. Additionally, downstream signalling pathways were not explored, although VEGFR-2 is known to dimerise and autophosphorylate upon ligand binding to transduce signals predominantly through PLCγ and PKC [30,63], from which point there are well-characterised mechanisms of neurite growth and neurogenesis, such as activation of MAPK/ERK and STAT3 signalling [37], and epigenetic regulation such as inactivation of histone deacetylase 5 [64]. Future work should aim to characterise whether manipulation of these pathways can attenuate the anti-neurogenic effects of sFlt-1. Lastly, the precise role of astrocytes could be explored further, by selective knockdown of VEGFA and VEGFR-2 in neurons or astrocytes only. Overall, it is clear from the present findings that sFlt-1 impairs neuronal development independently of its effects on the vasculature, and in that regard may be considered an anti-neurogenic, as well as an anti-angiogenic, factor. Given that the foetal brain is likely to be exposed to elevated and sustained sFlt-1 concentrations during PE, these findings may provide important insights into the potential pathogenic mechanisms mediating the relationship between the disorder and the sub-optimal neurodevelopmental trajectories of exposed offspring.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- DIV

Days in vitro

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s mixture

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- FGF2

Fibroblast growth factor 2

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HDP

Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy

- ID

Intellectual disability

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LSD

Least significant difference

- MBP

Myelin basic protein

- NPC

Neural progenitor cell

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PE

Pre-eclampsia

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- PlGF

Placental growth factor

- RA

Retinoic acid

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- sFlt-1

Soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1

- VEGFA

Vascular endothelial growth factor A

- VEGFR

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Contributor Information

Cathal M. McCarthy, Email: cmccarthy@ucc.ie.

Gerard W. O'Keeffe, Email: g.okeeffe@ucc.ie.

Data Availability

All data generated during this study are included in this article and all datasets from which conclusions are based are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

CRediT Author Contribution

Aaron Barron: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Lauren Barrett: Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. Jetro J. Tuulari: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Linnea Karlsson: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Hasse Karlsson: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Cathal M. McCarthy: Formal analysis, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. Gerard W. O'Keeffe: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Writing—review & editing.

Ethics Approval

SH-SY5Y and ReNcell® VM cells are commercially available, and no ethics approval was required.

References

- 1.Magee L.A., Brown M.A., Hall D.R., Gupte S., Hennessy A., Karumanchi S.A.et al. (2022) The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertension 27, 148–169 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abalos E., Cuesta C., Grosso A.L., Chou D. and Say L. (2013) Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur. J. Obstetrics Gynecol. Reproduct. Biol. 170, 1–7 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li P., Xiong T. and Hu Y. (2021) Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and risk of asthma in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 11, e046769 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C.S., Nohr E.A., Bech B.H., Vestergaard M., Catov J.M. and Olsen J. (2009) Health of children born to mothers who had preeclampsia: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 201, 269.e1–269.e10 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun B.Z., Moster D., Harmon Q.E. and Wilcox A.J. (2020) Association of preeclampsia in term births with neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry 77823–829 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0306e200306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K., Yu T., Kang L., Lien Y. and Kuo P. (2021) Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and maternal hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 63, 1107–1113 10.1111/dmcn.14893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhen Lim T.X., Pickering T.A., Lee R.H., Hauptman I. and Wilson M.L. (2023) Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and occurrence of ADHD, ASD, and epilepsy in the child: A meta-analysis. Pregnancy Hypertension 33, 22–29 10.1016/j.preghy.2023.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maher G.M., O'Keeffe G.W., Kearney P.M., Kenny L.C., Dinan T.G., Mattsson M.et al. (2018) Association of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 809–819 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xing Q.-N., Liu Y.-C., Xuan D.-S., Shang H.-L., Zhao X. and Zhang X.-A. (2021) Diagnostic value of diffusion tensor imaging for infants' brain development retardation caused by pre-eclampsia. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2021, 1–7 10.1155/2021/5545178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rätsep M.T., Paolozza A., Hickman A.F., Maser B., Kay V.R., Mohammad S.et al. (2016) Brain structural and vascular anatomy is altered in offspring of pre-eclamptic pregnancies: A pilot study. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 37, 939–945 10.3174/ajnr.A4640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gumusoglu S.B.S., Chilukuri A.A.S.S., Hing B.W.Q.B., Scroggins S.M.S., Kundu S., J.A. Sandgrenet al. (2021) Altered offspring neurodevelopment in an arginine vasopressin preeclampsia model. Transl. Psychiatr. 11, 10.1038/s41398-021-01205-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ijomone O.K., Shallie P.D. and Naicker T. (2020) Oligodendrocytes death induced sensorimotor and cognitive deficit in N-nitro-l-arginine methyl rat model of pre-eclampsia. Neurochem. Res. 45, 902–914 10.1007/s11064-020-02969-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura N., Ushida T., Onoda A., Ueda K., Miura R., Suzuki T.et al. (2023) Altered offspring neurodevelopment in an L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rat model. Front. Pediatrics 11, 1168173 10.3389/fped.2023.1168173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst C. (2016) Proliferation and differentiation deficits are a major convergence point for neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Neurosci. 39, 290–299 10.1016/j.tins.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto R., Nakazawa T., Tsurusaki Y., Yasuda Y., Nagayasu K., Matsumura K.et al. (2016) Whole-exome sequencing and neurite outgrowth analysis in autism spectrum disorder. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 199–206 10.1038/jhg.2015.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barron A., Manna S., McElwain C.J., Musumeci A., McCarthy F.P., O'Keeffe G.W.et al. (2023) Maternal pre-eclampsia serum increases neurite growth and mitochondrial function through a potential IL-6-dependent mechanism in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Front. Physiol. 13, 10.3389/fphys.2022.1043481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott H., Phillips T.J., Stuart G.C., Rogers M.F., Steinkraus B.R., Grant S.et al. (2018) Preeclamptic placentae release factors that damage neurons: implications for foetal programming of disease. Neuronal Signaling 2, NS20180139 10.1042/NS20180139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rains M.E., Muncie C.B., Pang Y., Fan L.-W., Tien L.-T. and Ojeda N.B. (2021) Oxidative stress and neurodevelopmental outcomes in rat offspring with intrauterine growth restriction induced by reduced uterine perfusion. Brain Sci. 11, 78 10.3390/brainsci11010078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Souza V., Patil V., Pisal H., Randhir K., Joshi A., Mehendale S.et al. (2014) Levels of brain derived neurotrophic factors across gestation in women with preeclampsia. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 37, 36–40 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rana S., Lemoine E., Granger J. and Karumanchi S.A. (2019) Preeclampsia: pathophysiology, challenges, and perspectives. Circ. Res. 124, 1094–1112 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staff A.C., Braekke K., Harsem N.K., Lyberg T. and Holthe M.R. (2005) Circulating concentrations of sFlt1 (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1) in fetal and maternal serum during pre-eclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 122, 33–39 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer K.R., Tong S. and Kaitu'u-Lino T.J. (2017) Placental-specific sFLT-1: role in pre-eclamptic pathophysiology and its translational possibilities for clinical prediction and diagnosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 23, 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stepan H., Galindo A., Hund M., Schlembach D., Sillman J., Surbek D.et al. (2023) Clinical utility of sFlt-1 and PlGF in screening, prediction, diagnosis and monitoring of pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynecol.: Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynecol. 61, 168–180 10.1002/uog.26032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perales A., Delgado J.L., de la Calle M., García-Hernández J.A., Escudero A.I., Campillos J.M.et al. (2017) sFlt-1/PlGF for prediction of early-onset pre-eclampsia: STEPS (Study of Early Pre-eclampsia in Spain). Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynecol.: Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynecol. 50, 373–382 10.1002/uog.17373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogtmann R., Burk L.V., Serdar M., Kimmig R., Bendix I. and Gellhaus A. (2022) Systemic maternal human sFLT1 overexpression leads to an impaired foetal brain development of growth-restricted foetuses upon experimental preeclampsia. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longevity 2022, 10.1155/2022/3024032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turanov A.A., Lo A., Hassler M.R., Makris A., Ashar-Patel A., Alterman J.F.et al. (2018) RNAi modulation of placental sFLT1 for the treatment of preeclampsia. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1164–1173 10.1038/nbt.4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsao P.-N., Wei S.-C., Su Y.-N., Chou H.-C., Chen C.-Y. and Hsieh W.-S. (2005) Excess soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and low platelet counts in premature neonates of preeclamptic mothers. Pediatrics 116, 468–472 10.1542/peds.2004-2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia L., Zhou X.P., Zhu J.H., Xie X.D., Zhang H., Wang X.X.et al. (2007) Decrease and dysfunction of endothelial progenitor cells in umbilical cord blood with maternal pre-eclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 33, 465–474 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lara E., Acurio J., Leon J., Penny J., Torres-Vergara P. and Escudero C. (2018) Are the cognitive alterations present in children born from preeclamptic pregnancies the result of impaired angiogenesis? Focus on the potential role of the VEGF family Front. Physiol. 9, 1591 10.3389/fphys.2018.01591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simons M., Gordon E. and Claesson-Welsh L. (2016) Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 611–625 10.1038/nrm.2016.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maynard S.E., Min J.Y., Merchan J., Lim K.H., Li J., Mondal S.et al. (2003) Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 649–658 10.1172/JCI17189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabel K., Fabel K., Tam B., Kaufer D., Baiker A., Simmons N.et al. (2003) VEGF is necessary for exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 2803–2812 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin K., Zhu Y., Sun Y., Mao X.O., Xie L. and Greenberg D.A. (2002) Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. PNAS 99, 11946–11950 10.1073/pnas.182296499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okabe K., Fukada H., Tai-Nagara I., Ando T., Honda T., Nakajima K.et al. (2020) Neuron-derived VEGF contributes to cortical and hippocampal development independently of VEGFR1/2-mediated neurotrophism. Dev. Biol. 459, 65–71 10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenstein J.M., Mani N., Khaibullina A. and Krum J.M. (2003) Neurotrophic Effects of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor on Organotypic Cortical Explants and Primary Cortical Neurons. J. Neurosci. 23, 11036–11044 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11036.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khaibullina A.A., Rosenstein J.M. and Krum J.M. (2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes neurite maturation in primary CNS neuronal cultures. Dev. Brain Res. 148, 59–68 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogunshola O.O., Antic A., Donoghue M.J., Fan S.Y., Kim H., Stewart W.B.et al. (2002) Paracrine and autocrine functions of neuronal vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11410–11415 10.1074/jbc.M111085200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Licht T., Eavri R., Goshen I., Shlomai Y., Mizrahi A. and Keshet E. (2010) VEGF is required for dendritogenesis of newly born olfactory bulb interneurons. Development 137, 261–271 10.1242/dev.039636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Licht T., Goshen I., Avital A., Kreisel T., Zubedat S., Eavri R.et al. (2011) Reversible modulations of neuronal plasticity by VEGF. PNAS 108, 5081–5086 10.1073/pnas.1007640108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu X., Stoyanova E.I., Lemiesz A.E., Xing J., Mash D.C. and Heintz N. (2018) Species and cell-type properties of classically defined human and rodent neurons and glia. eLife 7, 10.7554/eLife.37551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jezierski A., Baumann E., Aylsworth A., Costain W.J., Corluka S., Banderali U.et al. (2022) Electrophysiological- and neuropharmacological-based benchmarking of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived and primary rodent neurons. Stem Cell Rev. Reports 18, 259–277 10.1007/s12015-021-10263-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donato R., Miljan E.A., Hines S.J., Aouabdi S., Pollock K., Patel S.et al. (2007) Differential development of neuronal physiological responsiveness in two human neural stem cell lines. BMC Neurosci. 8, 1–11 10.1186/1471-2202-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wylie S.R. and Chantler PD. Myosin I.I.A. (2003) Drives neurite retraction. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4654–4666 10.1091/mbc.e03-03-0187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine R.J., Qian C., Maynard S.E., Yu K.F., Epstein F.H. and Karumanchi S.A. (2006) Serum sFlt1 concentration during preeclampsia and mid trimester blood pressure in healthy nulliparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194, 1034–1041 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olmos A., Díaz L., Avila E., Barrera D., López-Marure R., Biruete B.et al. (2013) Associations between insulin-like growth factor I, vascular endothelial growth factor and its soluble receptor 1 in umbilical serum and endothelial cells obtained from normotensive and preeclamptic pregnancies. Growth Factors 31, 123–129 10.3109/08977194.2013.802692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackenzie F. and Ruhrberg C. (2012) Diverse roles for VEGF-A in the nervous system. Development 139, 1371–1380 10.1242/dev.072348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ge D., Song K., Guan S., Dai M., Ma X., Liu T.et al. (2012) Effect of the neurosphere size on the viability and metabolism of neural stem/progenitor cells. African J. Biotechnol. 11, 3976–3985 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dráberová E., Del Valle L., Gordon J., Marková V., Šmejkalová B., Bertrand L.et al. (2008) Class III β-tubulin is constitutively coexpressed with glial fibrillary acidic protein and nestin in midgestational human fetal astrocytes: implications for phenotypic identity. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 67, 341–354 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31816a686d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rieske P., Azizi S.A., Augelli B., Gaughan J. and Krynska B. (2007) A population of human brain parenchymal cells express markers of glial, neuronal and early neural cells and differentiate into cells of neuronal and glial lineages. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 31–37 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song Y., Subramanian K., Berberich M.J., Rodriguez S., Latorre I.J., Luria C.M.et al. (2019) A dynamic view of the proteomic landscape during differentiation of ReNcell VM cells, an immortalized human neural progenitor line. Scientific Data 6, 1–17 10.1038/sdata.2019.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sordini L., Garrudo F.F.F., Rodrigues C.A.V., Linhardt R.J., Cabral J.M.S., Ferreira F.C.et al. (2021) Effect of electrical stimulation conditions on neural stem cells differentiation on cross-linked PEDOT:PSS Films. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 73 10.3389/fbioe.2021.591838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kashiwagi T., Takazawa Y., Kagawa T. and Taga T. (2023) Organization of self-advantageous niche by neural stem/progenitor cells during development via autocrine VEGF-A under hypoxia. Inflammation Regeneration 43, 1–15 10.1186/s41232-022-00254-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayakawa K., Pham L.D.D., Som A.T., Lee B.J., Guo S., Lo E.H.et al. (2011) Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates the migration of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. J. Neurosci. 31, 10666 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1944-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Selvaraj D., Gangadharan V., Michalski C.W., Kurejova M., Stösser S., Srivastava K.et al. (2015) A functional role for VEGFR1 expressed in peripheral sensory neurons in cancer pain. Cancer Cell 27, 780 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Micheli L., Parisio C., Lucarini E., Vona A., Toti A., Pacini A.et al. (2021) VEGF-A/VEGFR-1 signalling and chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain: therapeutic potential of a novel anti-VEGFR-1 monoclonal antibody. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 40, 1–19 10.1186/s13046-021-02127-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chapouly C., Argaw A.T., Horng S., Castro K., Zhang J., Asp L.et al. (2015) Astrocytic TYMP and VEGFA drive blood-brain barrier opening in inflammatory central nervous system lesions. Brain: A J. Neurol. 138, 1548–1567 10.1093/brain/awv077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu W.K., Georgiadis A., Copland D.A., Liyanage S., Luhmann U.F.O., Robbie S.J.et al. (2015) IL-4 regulates specific Arg-1+ macrophage sFlt-1-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 2324–2335 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu B., Thornton C., Tooher J. and Hennessy A. (2009) Exogenous soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sFlt-1) regulates Th1/Th2 cytokine production from normal placental explants via intracellular calcium. Hypertens. Pregnancy 28, 448–456 10.3109/10641950902777721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao Q., Ishibashi M., Hiasa K.I., Tan C., Takeshita A. and Egashira K. (2004) Essential role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiotensin II-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Hypertension 44, 264–270 10.1161/01.HYP.0000138688.78906.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryu J.K., Cho T., Choi H.B., Yu T.W. and McLarnon J.G. (2009) Microglial VEGF receptor response is an integral chemotactic component in Alzheimer's disease pathology. J. Neurosci. 29, 3 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2888-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu C., Xiong Z., Chen X., Lu Z., Zhou G., Wang D.et al. (2011) Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 inhibits migration of human monocytic THP-1 cells in response to VEGF. Inflamm. Res. 60, 769–774 10.1007/s00011-011-0332-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allen R.E., Rogozinska E., Cleverly K., Aquilina J. and Thangaratinam S. (2014) Abnormal blood biomarkers in early pregnancy are associated with preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 182, 194–201 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takahashi T., Yamaguchi S., Chida K. and Shibuya M. (2001) A single autophosphorylation site on KDR/Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-gamma and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. EMBO J. 20, 2768–2778 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mazzocchi M., Goulding S.R., Morales-Prieto N., Foley T., Collins L.M., Sullivan A.M.et al. (2022) Peripheral administration of the Class-IIa HDAC inhibitor MC1568 partially protects against nigrostriatal neurodegeneration in the striatal 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 102, 151–160 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this article and all datasets from which conclusions are based are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.