Editor:

Obstructive uterovaginal anomalies may cause severe pain, requiring urgent intervention (1,2). As a result, interventional radiologists have become more involved in managing outlet obstruction–related pain in these patients by draining the hematometrocolpos transabdominally. This letter presents a technique that can be used by interventional radiologists to assist these patients and their providers when immediate surgery is inappropriate, menstrual suppression alone is inadequate, and time for maturation is required (3).

This letter presents a case report of the management of a 13-year-old girl with a complex mental health history in whom vaginal outlet obstruction was diagnosed. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval. Magnetic resonance imaging, the gold standard for imaging the length of vaginal outlet obstruction, revealed complete vaginal agenesis, hematometrocolpos, and 2 kidneys (Fig 1). The patient was on menstrual suppression and had undergone an attempted hymenectomy (Fig 2). On examination, she had a patent hymen with a defect of 1 cm in depth because of the aborted procedure. On rectal examination, a palpable bulge was noted approximately 3 cm from the anus. Owing to her lack of readiness to manage the postoperative care of a vaginal pull-through procedure (ie, vaginal stent placement and dilation), definitive surgery was not attempted to avoid the risk of stenosis and the development of a pelvic infection (1,2,4). Instead, laparoscopic drainage of 150 mL of blood from the hematometrocolpos was performed, and the patient’s pain decreased (Fig 3). A postoperative ultrasound (US) to confirm resolution of the hematometrocolpos was not performed. The patient continued menstrual suppression and started pubertal suppression with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist before discharge. She was readmitted 1 week later because of severe pain and redemonstration of the hematometrocolpos, which was likely due to the gonadotropin flare causing menstrual bleeding in the setting of an incomplete laparoscopic evacuation. The department of interventional radiology was then consulted for uterine drainage.

Figure 1.

A sagittal view T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showed a distance of 4 cm from the base of the hematocolpos to the vaginal introitus (red caliper).

Figure 2.

Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound image showed the hematometrocolpos at the initial presentation. The cervix, defining the boundary between the blood-filled uterine cavity and the vagina, is outlined in red.

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic view of the hematometrocolpos at the time of laparoscopic drainage showed the left hematosalpinx (yellow arrow), left ovary (black arrow), superior vagina (asterisk), hematocolpos (blue outlines), dilated uterine body (green arrow), and right hematosalpinx (blue arrow). An adhesion was also noted from the left fallopian tube to the base of the uterine body (white arrowhead).

Under US guidance, a 4-F, 7-cm Yueh Centesis Catheter Needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) was advanced transabdominally into the lower cervicovaginal region of the hematoma. A wire was advanced cranially under fluoroscopy guidance, and the tract was dilated to accommodate a 10.2-F, 25-cm pigtail drain (Cook Medical) (Fig 4). A total of 2 mg of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; Genentech, South San Francisco, California) was injected into the cavity for hematoma lysis and drainage. Over 24 hours, a total of 6 mg of tPA was administered with minimal drain output, and increased pain.

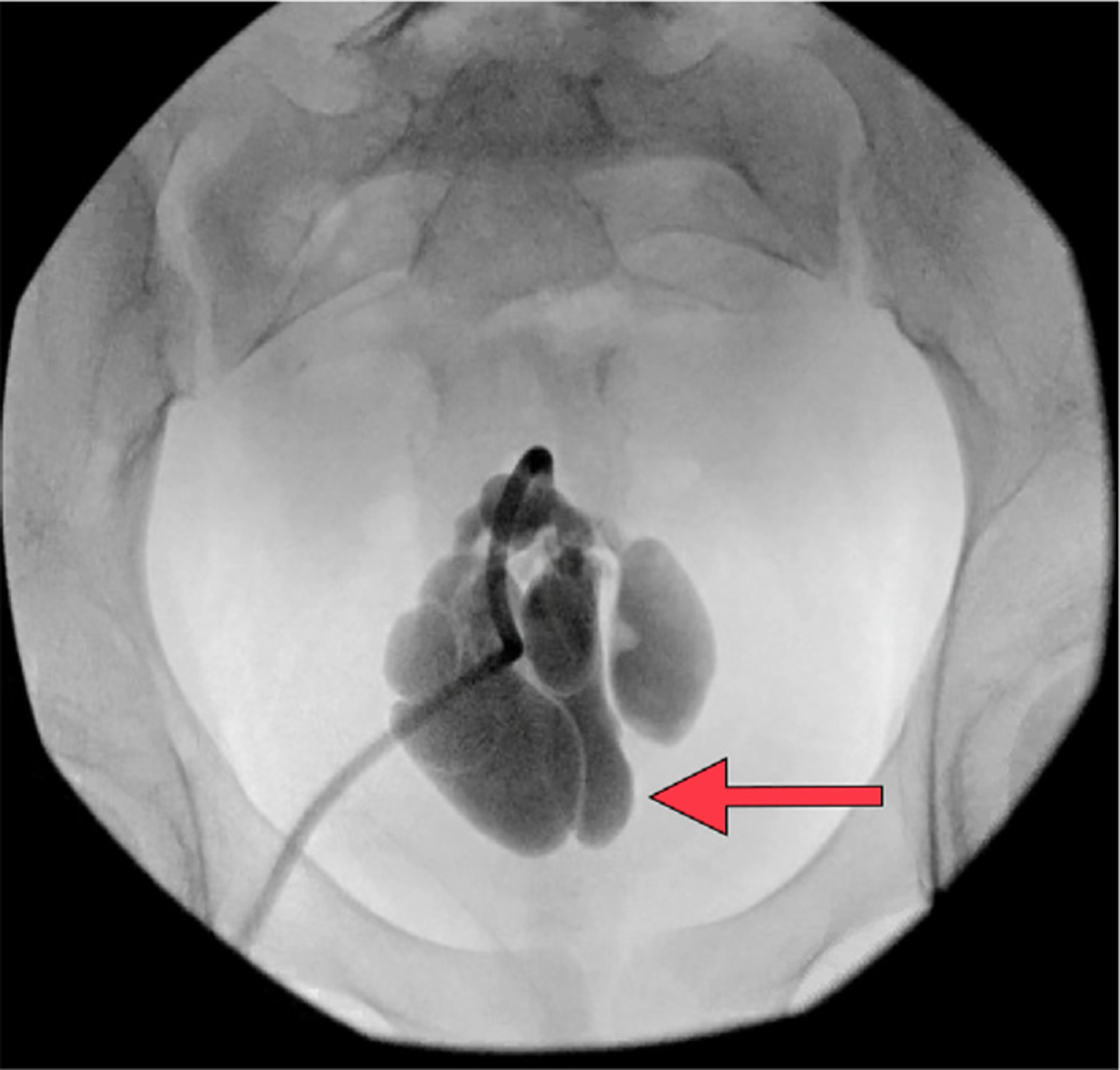

Figure 4.

An anteroposterior fluoroscopic image showed contrast medium injected (arrow) through the drain, retained in the obstructed uterus.

The patient underwent an additional procedure under anesthesia. Drain placement was confirmed with contrast medium injection, and a total of 8 mg of tPA was administered to further lyse the hematoma. Under fluoroscopic guidance, an Amplatz 80-cm guide wire (Cook Medical) was advanced cranially into the fluid collection. The guide wire and catheter (4-F 40 cm Kumpe; Angiodynamics, Latham, New York) were used to mechanically disrupt the hematoma (Fig 5). A 12-F, 25-cm pigtail drain with extra side holes (Cook Medical) was advanced over the wire, and irrigation and aspiration of 350 mL of viscous blood and clot was performed. At case completion, minimal residual blood was noted (Fig 6). The drain remained in place for 48 hours with minimal output. Repeat US confirmed resolution of the hematometrocolpos. The drain was removed, and the patient was discharged in stable condition; she returned at 6 weeks with minimal accumulation of blood on US.

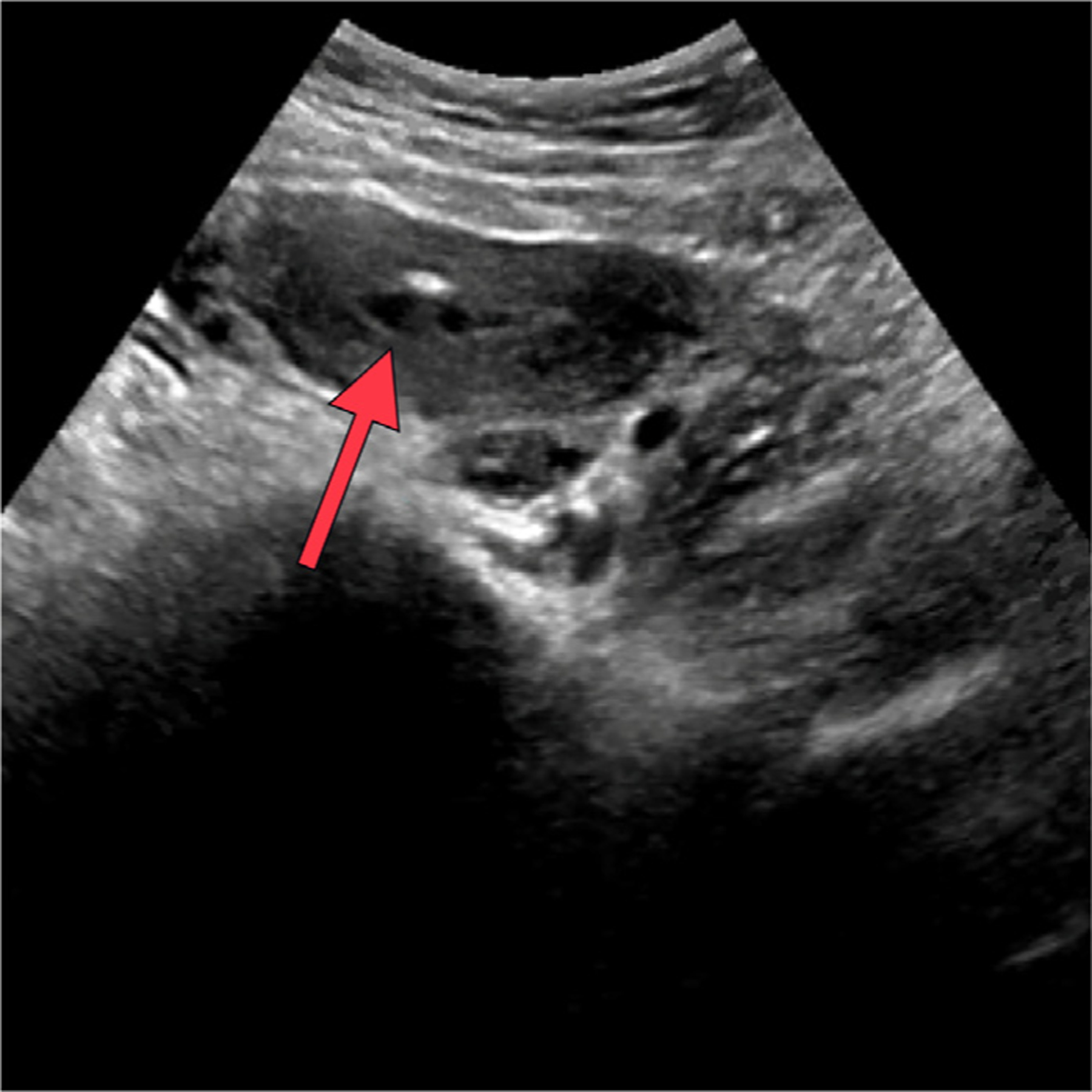

Figure 5.

Sagittal view ultrasound of the uterus showed the drain (arrow) within the hematometrocolpos.

Figure 6.

Sagittal view ultrasound demonstrated resolution of the hematometrocolpos (arrow).

Percutaneous drainage of the hematoma under US guidance was the best minimally invasive intervention in this case because it provided ultrasonographic feedback and visual evidence of resolution of the hematometrocolpos. To be successful, the drainage required use of generous amounts of tPA (a total of 16 mg in this case), catheter manipulation, and larger modified drains to assist with hematoma evacuation. Once resolution was confirmed, long term catheter drainage for passive collection was not needed because there was minimal output or accumulation after intervention, especially with concurrent menstrual suppression.

This technique is a safe and helpful adjunct to the techniques already available for the management of hematometrocolpos (ie, laparoscopic drainage and menstrual suppression). This is especially useful in the adolescent population when definitive surgery is often postponed, as in this adolescent patient, because vaginal agenesis in the patient was >3 cm (measured from the distal aspect of the hematocolpos to the introitus). Vaginal agenesis in the patient measured 4 cm in length, increasing the risk of stricture and, as a result, requiring postoperative vaginal stent placement and/or dilation. Many adolescent patients, similar to this patient, are often unable to participate in this type of postoperative care. Therefore, definitive management is deferred, and techniques such as IR drainage of the hematometrocolpos function as a bridge in the acute setting while menstrual suppression is instituted (4).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant (Z1A HD008985) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, United States.

Footnotes

K.S. has not identified a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jessica R. Long, Pediatric and Adolescent Division, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr., 8N248, MSC1840, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Veronica Gomez-Lobo, Pediatric and Adolescent Division, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr., 8N248, MSC1840, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Karun Sharma, Interventional Radiology Division, Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel V, Gomez-Lobo V. Obstructive anomalies of the gynecologic tract. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2016; 28:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Management of acute obstructive uterovaginal anomalies: ACOG Committee Opinion, number 779. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133:e363–e371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams A, Somasundaram A, Gill A, Childress K. 46. Management of hematocolpos in lower vaginal atresia by image-guided drainage with interventional radiology: a case series. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2021; 34:257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansouri R, Dietrich JE. Postoperative course and complications after pull-through vaginoplasty for distal vaginal atresia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015; 28:433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]