This article provides recommendations—evidence based where possible—to guide general practitioners in their use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in adults with heart failure. The development group assumes that doctors will use their knowledge and judgment in applying the principles and recommendations given below in managing individual patients, since recommendations may not be appropriate for use in all circumstances. Doctors must take the decision to adopt any particular recommendation in the light of available resources and the circumstances of each patient. The statements accompanied by categories of evidence (cited as Ia, Ib, II, III, IV) and recommendations classified according to their strength (A, B, C, or D) are as described in our previous article (and in the box).1 All recommendations are for general practitioners and apply to adult patients with heart failure attending general practice. This is a summary of the full guideline.2

Summary points

Heart failure is a common condition in general practice and has a poor prognosis

Only 20-30% of these patients are currently prescribed an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

All patients with symptomatic heart failure and evidence of impaired left ventricular function should be treated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; so should patients with a recent myocardial infarction and evidence of left ventricular function

Left ventricular function should ideally be assessed by echocardiography or radionuclide measurements

Strength of recommendation

A—Directly based on category I evidence B—Directly based on category II evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I evidence C—Directly based on category III evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I or II evidence D—Directly based on category IV evidence or extrapolated recommendation from category I, II or III evidence Categories of evidence Ia—Evidence from meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Ib—Evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial IIa—Evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation IIb—Evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study III—Evidence from descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies, and case-control studies IV—Evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical experience of respected authorities, or both

Symptomatic heart failure

Prevalence and incidence of symptomatic heart failure in adults

Statement: heart failure is a common chronic condition with a very poor prognosis (III)

With a list size of 2000 patients, a general practitioner will see about 20 patients with heart failure each year, 10 of whom will be new cases.3 Reported prevalence rates range from 0.4% to 2%.4–7 A general practitioner can expect about four admissions to hospital in patients with heart failure each year.8 Half these patients will die within four years, and half of patients with severe heart failure will die within one year.9

Only 20-30% of patients assessed by their general practitioner as having heart failure are prescribed an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.4,10 Most patients who are investigated for heart failure have a chest x ray and electrocardiogram, but only about a third have echocardiography.4–7 Diagnosis by clinical assessment has been estimated to be correct in about half of cases when confirmed by echocardiogram.6–11

Clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness

Clinical effectiveness

Statement: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are effective in treating heart failure. They reduce mortality in symptomatic patients who have a reported left ventricular ejection fraction of about 35% or less (Ia)

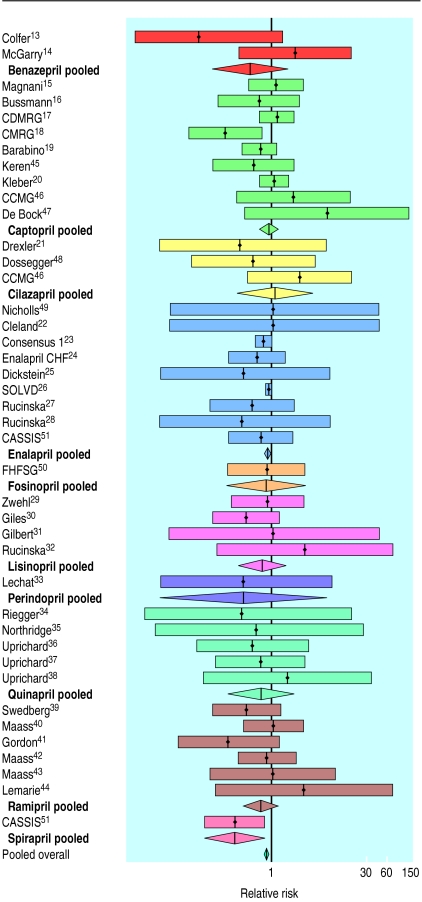

Garg and Yusuf reported a meta-analysis of 32 randomised trials comparing angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and placebo in patients with heart failure.12 These trials were of at least eight weeks’ duration and had total mortality, analysed in relation to intention to treat, as their outcome. Besides these 32 studies,13–44 we identified a further seven studies (nine comparisons)45–51 that met the criteria applied by Garg and Yusuf. The pooled relative risk of mortality, using a fixed effects model, was 0.83 (95% confidence interval 0.76 to 0.90) when taking an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, with no evidence of heterogeneity of effect (Q=34.71, df=40, P=0.71) (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Relative risk (95% confidence interval) of mortality in placebo controlled trials of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors grouped in relation to drug. CDMRG=Captopril-Digoxin Multicentre Research Group; CMRG=Captopril Multicentre Research Group; CCMG=Cilazapril-Captopril Multicentre Group; Enalapril CHF=Enalapril Congestive Heart Failure Investigators; SOLVD=Study of Left Ventricular Disease Investigators; CASSIS=Czech and Slovak Spirapril Intervention Study Investigators; FHFSG=Fosinopril Heart Failure Study Group

In the studies of left ventricular function treatment trial, 2569 patients with overt but stabilised heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less were randomised to treatment with enalapril or placebo and were followed up for an average of 41 months.26 The average benefit from angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in this trial was 2.44 months of extended life (calculated using Irwin’s restricted mean based on original patient data).52 Because trial data were analysed on an intention to treat basis, this estimate of benefit describes the effect of introducing routine treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors for patients with clinical signs of heart failure and an ejection fraction of 35% or less. (Note that ejection fraction data should be regarded as semiquantitative. Low ejection fractions should be considered as a marker of important left ventricular dysfunction.)

Severity of heart failure

Statement: the beneficial effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are shown for patients with a reported left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less (Ib): the greater the impairment, the greater the benefit (Ib)

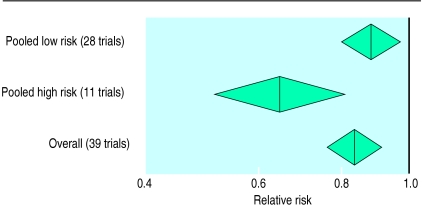

The studies of left ventricular function treatment26 and prevention53 trials both show that the size of benefit is correlated with the ejection fraction: the lower the ejection fraction the greater the benefit. Stratified meta-analyses of placebo controlled trials support these conclusions. If studies are divided into two groups—one (the low risk group) with a normalised annual mortality of up to 15% over the intervention and control groups13,15,17,19,20,22,25,26,28,29,31–38,41–47,49,50 and one (the high risk group) with a rate of more than 15%14,16,18,21,23,24,27,30,39,40,51—the relative risk of mortality in the low risk group is 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.80 to 0.97) while that in the high risk group is 0.64 (0.51 to 0.81) (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Relative risk of mortality from all causes in trials of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors compared with placebo in relation to underlying low and high mortality risk of trial subjects

Heart failure and previous myocardial infarction

Statement: long term treatment trials in patients who have had myocardial infarction and have left ventricular dysfunction show that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors provide an important benefit (Ia)

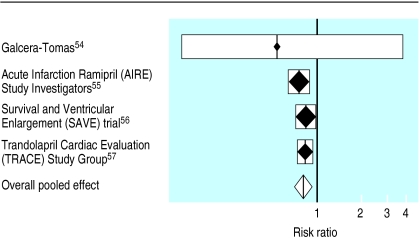

Four trials, in which more than 6000 patients were randomised to treatment, examined the use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors after myocardial infarction in patients with left ventricular dysfunction.54–57 Planned follow up was up to 50 months. Meta-analysis of these trials, using a fixed effects model, suggests that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction is beneficial (risk ratio 0.80; 0.74 to 0.88), with no evidence of variation between the estimates of effect provided by different trials (Q=1.01; df=3; P=0.80) (fig 3). These findings are reinforced by the positive results from the studies of left ventricular function treatment (SOLVD) trial, in which 65% of the patients included had had a myocardial infarction.26

Figure 3.

Risk ratio of survival after myocardial infarction in patients with evidence of left ventricular dysfunction

Quality of life

Statement: there is an improvement in symptoms and exercise tolerance when patients with symptomatic heart failure and a reported left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less are given an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (Ia) Statement: the value of the improvements in terms of general wellbeing of the patient is uncertain (Ia)

Narang et al reviewed 35 double blind placebo controlled trials in which the effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and placebo were compared.58 Altogether 3411 symptomatic patients were included. The ability to exercise for longer increased in 23 of 35 (66%) studies, while patients’ symptoms improved in 25 of 33 (76%) studies. All nine trials with a study size more than 50, follow up of three to six months, and in which a treadmill exercise test was used showed improved exercise capacity and symptoms.

The single largest and most general assessment of patients’ quality of life comes from a subsidiary analysis of the studies of left ventricular function treatment26 and prevention53 trials. In an analysis of patients enrolled in these treatment and prevention trials, Rogers found statistically significant improvements in self assessed dyspnoea and social functioning in those patients treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, although these improvements did not persist for the full two years of follow up.59 Another analysis of studies of left ventricular function data, using the observed frequency of dyspnoea, showed that a reduction in symptoms was achieved and maintained beyond two years in those treated with enalapril compared with those treated with placebo.60

Recommendations: clinical and cost effectiveness

All patients with symptomatic heart failure and evidence of impaired left ventricular function should be treated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (A)

Patients with recent myocardial infarction and evidence of left ventricular dysfunction should be treated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (A)

Treatment of heart failure with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors is cost effective (C)

Cost effectiveness

Statement: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors seem to be cost effective (III)

Trials consistently show a reduction in admissions to hospital for progressive heart disease in patients taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. It is unclear whether these are lasting reductions or simply reflect a “window in time” effect. More patients receiving angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors completed the trial follow up period without their heart disease progressing, but all patients deteriorated in following years. The data do not suggest that more admissions to hospital for other reasons offset reduced admissions to hospital for heart failure; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors seem to reduce admission to hospital for other causes in patients with symptoms of heart failure. We cannot assume that rates of admission to hospital during trials will be matched in clinical practice. However, the admission rate in the control arm of the studies of left ventricular function treatment trial matches precisely the rate found in general practice in England.3 On average, each general practitioner could expect to have four patients with heart failure admitted to hospital each year, and the studies of left ventricular function trial data show that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors might prevent (or delay) one of these hospital admissions. The annual cost of purchasing angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (at maintenance doses) ranges from £100 to £340 a year in relation to dosages reported in the British National Formulary.61 However, whether these maintenance doses are always therapeutically equivalent to the doses in the trial is unclear.

The incremental cost for each patient taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in primary care may vary from a small cost saving to a net cost of nearly £1600 over four years (table). In terms of cost effectiveness, these drugs, when used to treat heart failure, probably fall in the approximate range £0-£10 000 per life year gained, given the range of assumptions listed and remaining uncertainties. The important variables are the cost of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and savings on the costs of a hospital inpatient stay. Exploring the influence of compliance with treatment on the estimates of cost effectiveness presented is not possible in this simple model. The trial data, analysed on an intention to treat basis, reflect compliance achieved in the studies of left ventricular function treatment trial. The degree to which these findings are generalisable to general practice in the United Kingdom is uncertain. Where non-compliance means stopping treatment, both costs and benefits are forgone and the cost effectiveness ratios are not altered appreciably. Substantial cross over to treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in the placebo group in the studies of left ventricular function trial may mean that the attributable benefits are underestimated.

Recommendations: diagnosis

Left ventricular function should be evaluated in all patients with suspected heart failure who are being considered for treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in health districts with the facilities to perform echocardiography or radionuclide measurements (A)

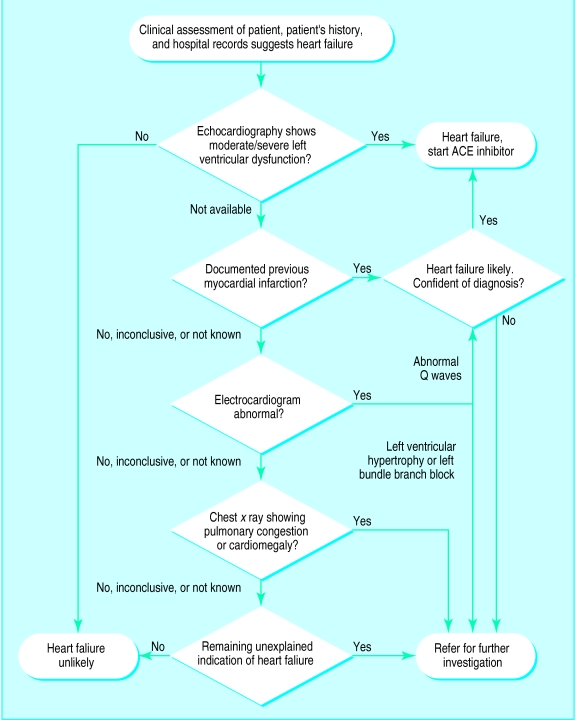

Where no facilities for measuring left ventricular function exist, all patients being considered for treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors should be managed in line with the flow chart in fig 4 (D)

Diagnosis of heart failure

Statement: patients with heart failure who will benefit from treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are best identified by echocardiography (Ia) Statement: there is some evidence that heart failure is misdiagnosed in general practice (III) Statement: if echocardiography or radionuclide measurement is not available, patients with heart failure who are likely to benefit from treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have to be identified clinically (IV)

The best way of identifying patients with impaired left ventricular function is with echocardiography or radionuclide measurement. If these investigations are not available, the combination of a patient’s past medical history, response to diuretics, chest x ray, and electrocardiogram can be used to identify the likelihood of heart failure, as set out in the flow chart in figure 4. The sensitivity and specificity of this flow chart are not known.62

Recommendation: choice of drug

As there is no good evidence of clinically important differences in the effectiveness of available angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, patients should be treated with the cheapest drug that they can effectively use (B)

Figure 4.

Algorithm for diagnosing suspected heart failure in primary care

Initiating and managing treatment

The range of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors that can be prescribed for treating heart failure and their dosages, cautions, contraindications, and side effects are described in section 2.5.5 of the British National Formulary.61 All recommendations for treatment apply only in the absence of recognised cautions, contraindications, side effects, or interactions, as documented in the formulary.

Choice of drug

Statement: no clinically important differences between the effectiveness of the various angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors have been reported, although most evidence is derived from randomised trials of enalapril (Ia)

From 39 trials (41 comparisons) there was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies, suggesting that the underlying drug effect was consistent across all contributing studies. Trials of enalapril provide greatest confidence in treatment effect for that drug.

Starting treatment

This section of the guideline is derived from the corresponding section in the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guideline for the management of heart failure.63

Recommendations: starting treatment

All patients being considered for treatment with converting enzyme inhibition should have plasma/serum creatinine and electrolytes measured (D) and blood pressure measured (D)

Patients should be considered for referral to hospital for assessment and supervised initiation of treatment if:Plasma/serum sodium concentration is <135 mmol/l (D)Plasma/serum creatinine concentration is >150 μmol/l (D)Systolic blood pressure is below 100 mm Hg (D)They require >80mg frusemide/day or equivalent (D)They show symptoms of severe heart failure (D)

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors should be used with increasing caution as the patient’s age increases (D)

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors should be used with caution in patients with severe peripheral vascular disease because of the possible association with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (D)

Treatment with these drugs should be monitored (A)

Drug dosages should be titrated upward over two to three weeks, aiming to reach the doses used in large scale clinical trials (A)

Diuretic treatment and hyperkalaemia

When treatment is initiated, diuretic drugs should be withheld for a brief period (at least 24 hours) to allow any volume depletion to resolve. Hyperkalaemia (plasma/serum potassium concentration >5.5 mmol/l) is a potential problem when angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are used. Potassium sparing diuretic drugs (for example, spironolactone, amiloride, triamterene) should be stopped in all patients who are being started on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, regardless of the serum potassium concentration. These drugs may be restarted if the patient remains hypokalaemic on full therapeutic doses of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. In addition, potassium supplements should usually be withheld unless the patient has a low serum potassium concentration (<4.0 mmol/l). If potassium supplements are continued, serum potassium concentrations must be monitored every few days until they are stable because of the risk of renal failure.

Patients at risk of “first dose hypotension”

Patients who are at high risk of hypotension after the first dose of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, initial systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg, or serum sodium <135 mmol/l) should be considered for referral to hospital for assessment and supervised initiation of treatment. If this is not possible they should be given a small dose of a short acting agent and monitored closely for two hours.64 The risk of hypotension increases with age.65 If the test dose is tolerated, they should be started on a small dose of an inhibiting drug such as enalapril (2.5 mg twice daily) or captopril (12.5 mg three times daily). Patients who are not at high risk of hypotension after the first dose should be started on a small dosage of a drug such as enalapril (2.5 mg twice daily) or captopril (12.5 mg three times daily).

Monitoring treatment

Patients receiving angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors should be monitored regularly. Before initiation of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition they should have their blood pressure, renal function, and serum potassium measured. These measurements should be repeated one week after initiation of treatment and again one week after each significant increase in dosage. The guideline development group could find no basis for recommending one monitoring interval over another in long term treatment, and felt that monitoring at least once a year was appropriate. Treatment should be modified if the patient develops: (a) an increase in the serum creatinine concentration of 50 μmol/1 or more; (b) a serum potassium concentration of 5.5 mmol/l or more; or (c) symptomatic hypotension (a documented fall in blood pressure with dizziness or weakness).

Recommendations: monitoring, compliance, and education

Doctors should ask regularly about any side effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (D)

Compliance with treatment is important and should be checked regularly, especially if symptom control is poor or drug dosage is about to be increased (D)

Patients should be offered education about their treatment (D)

Patients who develop renal insufficiency or hypotension should have their volume status reassessed. In patients who become hypovolaemic because of diuresis, the dose of any diuretic should be reduced and the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor drug may be tried again. These patients, though, should be considered for referral to a cardiologist, and all those who fail a second trial or who develop hyperkalaemia should not be retried on angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors but referred to a specialist.

Side effects

Side effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor drugs and contraindications are covered in the British National Formulary.61 Cough is common in patients taking these drugs, but it is also common in people with heart failure. Thus, patients who report cough while taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors should be evaluated to see whether this results from pulmonary congestion before stopping treatment is considered.

Compliance

Statement: compliance with treatment is important (IV). We identified no evidence on how compliance with treatment affects outcomes, but the guideline development group felt that the recommendation below reflected good clinical practice.

Patient education

Statement: education about his treatment is an important part of the management of any patient (IV)

Referral to a cardiologist

No evidence on referral to a cardiologist was identified by the group. The recommendations below are considered to reflect good clinical practice.

Recommendations: referral to a cardiologist

Referral to a cardiologist is appropriate for:Patients in whom diagnostic doubt exists (D)Patients whose treatment should be initiated in hospital (see “Initiating and managing treatment”) (D)Patients who present a problem in management (D)

Patients’ preferences should be taken into account in referral decisions (D)

Future research

In developing this guideline the group identified important issues that are not currently informed by research of a high quality. These include:

• (1) Uniform requirements and standards of practice for identifying left ventricular dysfunction—for example, reporting echocardiography;

• (2) Impact of access policies on assessing left ventricular dysfunction in primary care;

• (3) Optimum strategy for initiating and monitoring treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in primary care;

• (4) Good qualitative information on the impact of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on quality of life in patients with heart failure;

• (5) Influence of patient compliance on the effect of treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors;

• (6) Influence of patient education on the effect of treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors;

• (7) Carefully designed trials of the effect of starting treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with or without left ventricular dysfunction immediately after myocardial infarction.

Table.

Net cost and benefit per patient of treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for heart failure

| Assumptions about costs/benefits arising from addition of ACE inhibitors to current care* | Cost-benefit estimate

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Optimistic | Conservative | |

| ACE inhibitor £100/year or £340/year for 4 years | £400 | £1400 |

| Two GP visits or 2 outpatient visits needed to start treatment† | £20 | £138 |

| Reduced or no hospital admission ‡ | −£471 | £0 |

| GP visits related to heart failure unchanged or 1 extra visit/year for 4 years§ | £0 | £48 |

| Net cost range | −£206 | £1578 |

| Increased life expectancy (based on comparisons with placebo)[26] | 0.203 years | 0.203 years |

| Incremental cost effectiveness of ACE inhibitor ¶ | Small cost saving and health gain | £7770/life year gained |

Diagnosis costs excluded because of variation in tests performed or lack of adequate cost data and because costs may occur in any case as part of normal care.

Cost per GP consultation data65 and outpatient visit data66; no adequate data for costing additional blood tests.

Based on difference in studies on left ventricular disease (SOLVD) trial hospital admission in treatment and control groups,26 an inpatient stay of 14.5 days,5 and a cost of £125/inpatient day.67

Patients visit their GP once a year in relation to heart failure; we assume a reduction in visits is implausible, but treatment delays disease progression.

Survival gains were truncated in the SOLVD trial (4 years)26

Acknowledgments

The project steering group comprises: Professor Michael Drummond, Centre for Health Economics, University of York; Professor Andrew Haines, Department of Primary Care and Population Sciences, University College London Medical School and Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine; Professor Ian Russell, Department of Health Sciences and Clinical Evaluation, University of York; Professor Tom Walley, Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Liverpool.

Appendix

The guideline development group comprises the following members, in addition to the authors: Mr Joe Asghar, pharmaceutical adviser, Northumberland Health Authority; Mr Mark Campbell, prescribing unit manager, Regional Drug and Therapeutics Centre, University of Newcastle upon Tyne; Dr John Cleland, British Heart Foundation senior fellow, University of Glasgow; Dr John Harley, general practitioner, Stockton-on-Tees; Dr Barbara Holding, general practitioner, Seghill; Dr David Napier, general practitioner, Seaham; Dr Basil Penney, general practitioner, Darlington; Dr Wendy Ross, general practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne; Dr Malcolm Thomas, general practitioner, Guidepost, Northumberland; Dr Barnaby Thwaites, consultant cardiologist, Ashington.

Footnotes

Funding: The work was funded by the Prescribing Research Initiative of the UK Deparment of Health.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason J. North of England Evidence-Based Guidelines Development Project: methods of developing guidelines for efficient drug use in primary care. BMJ. 1998;316:1232–1235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North of England Evidence-Based Guideline Development Project. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline: ACE-inhibitors in the primary care management of adults with heart failure. Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne and Centre for Health Economics, University of York, 1997.

- 3.McCormick A, Fleming D, Charlton J. Morbidity statistics in general practice: fourth national study 1991-1992. London: HMSO; 1995. (Series MB5 No 3.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mair FS, Carowley TS, Bundred PK. Prevalence, aetiology and management of heart failure in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:77–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurray J, Hart W, Rhodes G. An evaluation of the cost of heart failure to the National Health Service in the UK. Br J Med Econ. 1993;6:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheeldon NM, MacDonald TM, Flucker CJ, McKendrick AD, McDevitt DG, Struthers AD. Echocardiography in chronic heart failure in the community. Q J Med. 1993;86:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parameshwar J, Shackell MM, Richardson A, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC. Prevalence of heart failure in three general practices in north west London. Br J Gen Pract. 1992;42:287–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Hospital episode statistics, 1993-4. London: Department of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Task Force on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis of heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark KW, Gray D, Hampton JR. Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure. Br Heart J. 1994;71:584–587. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.6.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remes J, Miettinen H, Reunanen A, Pyorala K. Validity of clinical diagnosis of heart failure in primary health care. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:315–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of ACE-inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. JAMA. 1995;273:1450–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colfer HT, Ribner HS, Gradman A, Hughes V, Kapoor A, Laideau JC.for the Benazepril Heart Failure Study Group. Effects of once-daily benazepril therapy on exercise tolerance and manifestations of chronic congestive heart failure Am J Cardiol 199270354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGarry R. Randomized, double blind, multicentre study comparing benazepril to digoxin and to placebo as add on therapy to diuretic in patients with CHF, NYHA class II-III during a 12 week treatment period, GHBA-194. Summit, NJ: Ciba-Geigy Pharmaceuticals; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnani B, Magelli C.for the Multicentre Research Group on Mild Heart Failure. Captopril in mild heart failure: preliminary observations of a long-term double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trial Postgrad Med J 198662(suppl B)153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bussmann WD, Storger H, Hadler D, Reifart N, Fassbinder W, Jungmann E, et al. Long-term treatment of severe chronic heart failure with captopril: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled long-term study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1987;9(suppl 2):S50–S60. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198700002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Captopril-Digoxin Multicentre Research Group. Comparative effects of therapy with captopril and digoxin in patients with mild to moderate heart failure. JAMA. 1988;259:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Captopril Multicenter Research Group. A placebo-controlled trial of captopril in refractory chronic congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:755–763. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barabino A, Galbariggi G, Pizzorni C, Lotti G. Comparative effects of long-term therapy with captopril and ibopamine in chronic congestive heart failure in old patients. Cardiology. 1991;78:289–296. doi: 10.1159/000174791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleber FX, Niemoller L, Doering W. Impact of converting enzyme inhibition on progression of chronic heart failure: results of the Munich mild heart failure trial. Br Heart J. 1992;67:289–296. doi: 10.1136/hrt.67.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drexler H, Banhardt BS, Meinertz T, Wollschlager H, Lehmann M, Just H. Contrasting peripheral short-term and long-term effects of converting enzyme inhibition in patients with congestive heart failure: a double blind, placebo controlled trial. Circulation. 1989;79:491–502. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleland JGF, Dargie HJ, Ball SG, Gillen G, Hodsman GP, Morton JJ, et al. Effects of enalapril in heart failure: a double blind study of effects on exercise performance, renal function, hormones and metabolic state. Br Heart J. 1985;54:305–311. doi: 10.1136/hrt.54.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enalapril CHF Investigators. Long-term effects of enalapril in patients with congestive heart failure: a multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Heart Failure. 1987;3:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickstein K, Barvik S, Aarsland T. Effect of long-term enalapril therapy on cardiopulmonary exercise performance in men with mild heart failure and previous myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:596–602. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90619-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucinska EJ. A double blind placebo controlled study to evaluate the effects of enalapril in patients with chronic heart failure. West Point, PA: Merck Sharpe & Dohme; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rucinska EJ. Enalapril vs placebo in previously untreated patients with CHF. West Point, PA: Merck Sharpe & Dohme; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwehl W, Rucinska E.for the Lisinopril Chronic Heart Failure Investigators. Long-term effects of lisinopril in patients with chronic heart failure: a multicentre, placebo-controlled trial Nicholls MG.A focus on the clinical effects of a long acting ACE-inhibitor in heart failure. 1990New York: Raven; 3140 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giles TD for Lisinopril Chronic Heart Failure Group. Lisinopril treatment of congestive heart failure results of a placebo controlled trial. Circulation. 1990;82:323. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert EM, Sandoval A, Larabee P, Renlund D, O’Connell JB, Bristow MR. Lisinopril lowers cardiac adrenergic drive and increases B-receptor density in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1993;88:472–480. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruckinska EJ. Lisinopril first line therapy in CHF. West Point, PA: Merck Sharpe & Dohme; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lechat P, Garnham J, Desche P, Bounhoure JP. Efficacy and acceptability of perindopril in mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1993;126:798–806. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riegger GAJ. The effects of ACE-inhibitors on exercise capacity in the treatment of congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;15(suppl 2):41–46. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199000152-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northridge DB, Rose E, Elder A, Raftery ED, Lahiri A, Elder AT, Shaw TRD, et al. A multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quinapril in mild chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:403–409. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uprichard A. A 16-week double blind, placebo-randomized, placebo controlled multicentre trial to evaluate the effects of withdrawal of quinapril hydrochloride on exercise tolerance in patients with mild to moderate congestive heart failure (906-276). Ann Arbour, MI: Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uprichard A. An 18-week double blind, optional titration, multicentre study to compare the efficacy and safety of orally administered quinapril hydrochloride with captopril and placebo in patients with congestive heart failure (906-226). Ann Arbour, MI: Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uprichard A. A 12-week double blind, placebo controlled study to determine the efficacy and safety of orally administered quinapril hydrochloride in patients with congestive heart failure (906-63). Ann Arbour, MI: Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swedberg K, Amtorp O, Gundersen T, Remes J, Nilsson B. Is maximal exercise testing a useful method to evaluate treatment of moderate heart failure [abstract]? Circulation. 1991;57:226. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maass L. Double blind comparative trial with ramipril and placebo in patients with heart failure (NYHA class III-IV) stabilised on digitalis and frusemides. Frankfurt: Hoechst; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon M. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of ramipril (HOE 498) in patients with congestive heart failure in a placebo-controlled trial. Somerville, NJ: Hoechst-Roussel Pharmaceuticals; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maass L. Efficacy and safety of ramipril (HOE 498) in patients with congestive heart failure in a double blind placebo controlled trial. Frankfurt: Hoechst; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maass L. Evaluation of the effect of ramipril (HOE 498) on exercise duration, invasive cardiac haemodynamics profiles and safety in patients with congestive heart failure. Frankfurt: Hoechst; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemarie JC. Multicentre double blind placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of ramipril administered orally for 24 weeks in the treatment of stable chronic congestive cardiac failure. Paris: Hoechst; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keren G, Pardes A, Eschar Y, Hansch E, Scherez J, Laniado S. Left ventricular filling dynamics by doppler echocardiography in dilated cardiomyopathy: one-year follow up in patients treated with captopril compared to placebo. Cardiology. 1992;81:196–206. doi: 10.1159/000175805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cilazapril-Captopril Multicentre Group. Comparison of the effects of cilazapril and captopril versus placebo on exercise testing in chronic heart failure patients: a double blind, randomized multicenter trial. Cardiology. 1995;86(suppl 1):34–40. doi: 10.1159/000176944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Bock V, Mets T, Romagnoli M, Derde MP. Captopril treatment of chronic heart failure in the very old. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M148–M152. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dossegger L, Aldor E, Baird MG, Braun S, Cleland JGF, Donaldson R, et al. Influence of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on exercise performance and clinical symptoms in chronic heart failure: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 1993;14(suppl C):18–23. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.suppl_c.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicholls MG, Ikram H. Espiner EA, Webster MWI, Fitzpatrick MA. Enalapril in heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;18:163–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02594.x. S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown EJ, Chew PH, MacLean A, Gelperin K, Ilgenfritz JP, Blumethal M.for the Fosinopril Heart Failure Study Group. Effects of fosinopril on exercise tolerance and clinical deterioration in patients with chronic congestive heart failure not taking digitalis Am J Cardiol 199575596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Widimsky J, Kremer HJ, Jerie P, Uhlir O.for the CASSIS investigators. Czech and Slovak spirapril intervention study (CASSIS): a randomized, placebo and active-controlled, double-blind muticentre trial in patients with congestive heart failure Eur J Clin Pharmacol 19954995–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karrison TG. Use of Irwin’s restricted mean as an index for comparing survival in different treatment groups—interpretation and power considerations. Controlled Clin Trials. 1997;18:151–167. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galcera-Tomas J, Antonio Nuno de la Roas J, Torres-Martinez G, Rodriguez-Garcia P, Castillo-Soria FJ, Canton-Martinez A, et al. Effects of early use of captopril on haemodynamics and short term ventricular remodelling in acute anterior myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1993;14:259–266. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet. 1993;342:821–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pfeffer MA, Branunwald E, Moy LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Cuddy TE, et al. for the SAVE Investigators. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial N Engl J Med 1992327669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlesen JE, Bagger H, Eliasen P. Lyngborg K, et al for the Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE) Study Group. A clincal trial of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1670–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Narang R, Swedberg K, Cleland JGF. What is the ideal study design for evaluation of treatment for heart failure? Insights from trials assessing the effect of ACE-inhibitors on exercise capacity. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:120–134. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogers WJ, Johnstone DE, Yusuf S, Weiner DH, Gallagher P, Bittner VA, et al. Quality of life among 5,025 patients with left ventricular dysfunction randomized between placebo and enalapril: the studies of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pouleur H. ACE-inhibitors in the treatment of clinical heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 1993;88(suppl 1):203–209. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72497-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.British national formulary. No 32. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. Heart failure: evaluation and care of patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. (Clinical practice guideline 11.) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frank GJ. The safety of ACE-inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure. Cardiology. 1989;76(suppl 2):56–57. doi: 10.1159/000174560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Neill CJ, Bowes SG, Sullens CM, Royston JP, Hunt WB, Denham MJ, et al. Evaluation of the safety of enalapril in the treatment of heart failure in the very old. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;35:143–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00609243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Department of Health; Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. The government’s expenditure plans 1994-95 to 1996-97. London: HMSO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy, Healthcare Financial Management Association. The health service financial database 1997 [CD ROM]. London: CIPFA; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Netten A, Dennett S. Unit costs of health and social care. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Canterbury; 1997. [Google Scholar]