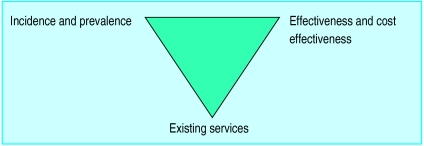

The first article in this series explained the importance of health needs assessment in the context of planning and delivering health care to populations.1 It mentioned the “epidemiological approach” to health needs assessment—the traditional public health approach of describing need in relation to specific health problems using estimates of the incidence, prevalence, and other surrogates of health impact derived from studies carried out locally or elsewhere. This approach has been be extended to the consideration, alongside these measures, of the ways in which existing services are delivered and the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of interventions intended to meet the needs thus described (fig 1).2 This is a logical extension as there is little point in estimating the burden of ill health (except for determining priorities for future research) if nothing can be done to reduce it.

Figure 1.

Components of health needs assessment. Modified from Stevens and Raftery2

Epidemiology has been defined as “the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specific populations and the application of this study to control of health problems.”3 It tends, for the most part, to use the “medical model” of health need, viewing need in terms of the occurrence of specific diseases and health related states rather than client groups. Descriptive epidemiology (as opposed to analytical epidemiology—the investigation of the determinants of health related states or events) describes the occurrence of disease in terms of person, place, and time:

Person—who the affected people are (in terms of their age, sex, occupation, socioeconomic group, etc);

Place—where they are when they get diseases and in what way prevalence and incidence vary geographically (locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally);

- Time—when people get diseases, whether this varies by, for example, season; and how disease occurrence is changing over time.

Summary points

- Epidemiological methods can be used to describe health needs in terms of the distribution of specific diseases

- Although incidence and prevalence do not necessarily equate with need, they are both important in describing the population burden of disease

- Specific epidemiological studies can be expensive and time consuming. Existing information from previous studies can be used to inform local needs if criteria for generalisability are met

- Routine sources of health information can suffer from inaccuracy and inappropriateness, but they can provide valuable descriptions of health and healthcare use in a defined population

Case definition

The usual starting point for any epidemiologically based needs assessment is the question, what is a case? Epidemiologists place great importance on case definition; yet, for a thorough health needs assessment, simple case definitions usually need to be expanded to include valid measures of severity.

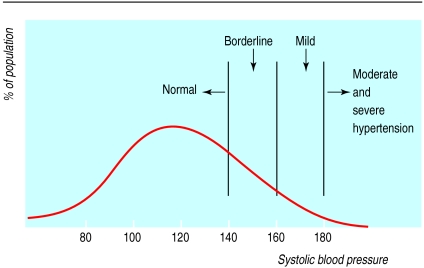

Patients who are cases may possess relatively clear characteristics which separate them from those who are not cases. Examples are patients with the florid symptoms or signs of hypertension, asthma, or diabetes. However, in most conditions, including these three, individuals are encountered who are close to the borderline between normality and abnormality (fig 2). For these, internationally agreed criteria are required and are available.4–6

Figure 2.

Classification of hypertension by systolic blood pressure shows the continuum from normal to abnormal

Such criteria may seem arbitrary but are, or at least should be, based on the probability of the future occurrence of specified outcomes known to be associated with the relevant condition. They may be based on physical signs or symptoms, or on physiological or biochemical characteristics which need to be measured by appropriate and standardised tests—for example, valid and repeatable questionnaires or physiological or biochemical tests. The criteria may change from time to time as further knowledge accrues but should not vary from place to place if estimates of incidence and prevalence are to be at all generalisable.

Incidence and prevalence

Incidence and prevalence are measures fundamental to the science of epidemiology. Both of these require the estimation of the numerator—the number of new cases observed (in the case of incidence) or the number of cases present in a population (in the case of prevalence)—and the estimation of the denominator (the number of people in the population at risk). Incidence is a rate (it has a time dimension) and prevalence is a proportion that is measured at a point in time but does not have a time dimension.

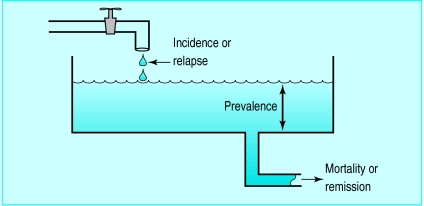

Neither prevalence nor incidence necessarily equates with need, but knowledge of incidence and prevalence is usually an essential starting point for the assessment of need. Prevalence increases if incidence (or the rate of relapse) increases. It also increases if the mortality (or remission) decreases. The relation between these variables is best summarised as the “prevalence pool” concept (fig 3). Only a part of this prevalence pool may be visible at any one time if any proportion of the existing cases of a disease remains unrecognised. Unrecognised cases may be those at an early stage of development or may be the least severe.

Figure 3.

Prevalence pool

In health needs assessment it may be important to estimate both incidence and prevalence. Incidence is particularly important for diseases or conditions that are of short duration (such as many communicable diseases) or for those for which a substantial amount of the healthcare input occurs shortly after diagnosis (myocardial infarction, for example). Prevalence is particularly important when the duration of disease is long—for example, asthma, diabetes, or multiple sclerosis. Several types of incidence and prevalence may be used in needs assessment:

Stratum specific estimates: for example, age specific—for those in a given age group;

Crude estimates: crudely calculated by summing the numerators over all strata (for example, all ages) and dividing by the denominator of the total population;

Standardised estimates: taking into account that the populations being compared may differ in terms of age or another important attribute.

Standardised estimates may be derived by the direct or indirect method. In the direct method, the stratum specific estimates are taken from the population being standardised (this might be a town or locality) and applied to the stratum specific population figures of the standard population (that of the country, for example). The incidence or prevalence that would pertain in that population if those of the town or locality were applied to it can thus be calculated. In the indirect method, the process is reversed. The direct method is more usual and, in most cases, preferable. Using the indirect method is justified when the data items required for the direct method are not available and when small numbers in the stratum specific estimates in the population being standardised make them statistically unstable. The standardised mortality ratio is a ratio derived from the technique of indirect standardisation.

Generalisability

The NHS Management Executive set up the district health authority project in 1990 to support health authorities in their responsibility for assessing needs. This led to a series of reviews of healthcare needs assessment.2 The aim of these reviews was to give practical guidance to purchasers on moving from a service led healthcare system to a needs led healthcare system. They provided an “off the shelf” guide to population needs for important health topics such as asthma and stroke.

Such general information, however, is often disregarded on the grounds that “it’s not like that here.” Standard epidemiological tools and guidance are extremely important. However, existing techniques are often crude, particularly when measuring morbidity. In the absence of dedicated research, evidence of morbidity is often derived from mortality data, and when research is available, extrapolation to different populations can disguise underlying variations.7 Clearly, populations will differ in age, sex, socioeconomic and ethnic mix, and other attributes, or there may be other legitimate reasons for thinking that work carried out elsewhere is not applicable (use of an incorrect case definition, for example). Issues of generalisability can usually be divided into four broad areas:

Case definitions—are they acceptable?

The time since the study was carried out—is the information still timely?

Is the study sound in other respects—methods of ascertainment (numerators) and demographic information (denominators)?

Have the data been presented (or are they available) for the relevant strata of known confounders? (The term “confounders” is used here to encompass attributes which influence incidence or prevalence such as age, sex, and socioeconomic or ethnic group.)

Diabetes is an example of a condition for which knowledge of incidence and prevalence in relation to confounders is essential if any valid estimate of need is to be made. In general practices that are known to have identified their diabetic patients comprehensively, the prevalence of diabetes shows a close and totally expected relation with the proportion of the practice list aged 65 years and over.8 Thus, practices that are unsure of the completeness of their diabetes register can get some indication of how close they are to complete ascertainment by comparing their observed prevalence with that expected on the basis of this relation with age. However, this holds only if the practice population has a similar composition, in terms of ethnic origin, to the practices on which the initial observations have been made. Since it is known that the prevalence of diabetes varies between ethnic groups and, equally important, that the relation between prevalence and age is different in different ethnic groups, the ethnic composition of the practice needs to be taken into account.

Undertaking an epidemiological survey

Routine sources can provide only limited descriptions of disease; for more details, special surveys may be required. There are two main types of descriptive survey: prevalence (cross sectional) surveys and longitudinal surveys. These principles apply to all surveys, whether they are to describe disease or to provide patients’ perspectives.

Surveys cost time and money. It is important to ensure that the information wanted is not available from routine sources

There should be a clear aim for the survey. What disease, or risk factor, is being measured? What is the case definition? What is the population of interest?

Good planning is needed. Staff and resources will be needed to carry out the survey and produce a report

Sample size for the survey must be calculated. This is usually a balance between the need for precision (more precise estimates of incidence and prevalence require larger samples) and the resources and time available

Recruitment of the sample must be considered. A sampling frame must be chosen and from this the sample selected randomly, systematically, or purposefully

The survey instrument (a symptom questionnaire, quality of life measure, physiological measurement, or laboratory test) should be valid, reliable, and repeatable

Steps should be taken to ensure a high response rate. Questionnaires should be piloted

Although no convincing relation has been found between prevalence of diabetes and socioeconomic group, relations have been found between outcomes of diabetes and socioeconomic status: worse outcomes in the more disadvantaged groups are worse. For this reason, any estimate of need (“the ability to benefit from care”2) for diabetes services must take socioeconomic status into account.

If the four aspects described above are satisfied then there is no reason why information from other localities cannot be applied to the local situation. To do so, with all reasonable care, can save precious resources which might otherwise be squandered in carrying out yet another health needs assessment on a given health problem merely because of a misplaced enthusiasm for locally derived data.

Small populations

“Locality based health needs assessment”—needs assessment dealing with populations smaller than district health authorities or their equivalents—has the advantage of allowing knowledge of the local scene to be used in planning local services. The use of local data, to the exclusion of data available from elsewhere, needs to be carefully considered. Apart from the cost implications of repeating locally what may have been done perfectly well elsewhere and can be extrapolated, statistical considerations need to be taken into account when assessing the frequency of relatively rare events. Even diseases that are common enough to be regarded as major public health problems (for example, carcinoma of the cervix) occur relatively infrequently in small populations.

National sources of health information in the United Kingdom

Population:

Census data can be used to describe populations at a district or electoral ward level by age, sex, ethnic group, or socioeconomic status

Census information on variables such as unemployment and overcrowding can be used to produce indices of deprivation for electoral wards (Jarman index, Townsend score)

Mortality:

National registration of deaths and causes of death provide comprehensive (though not always accurate) information on mortality

Perinatal and infant mortality “rates” (they are not rates but proportions) are used for comparisons of the quality of health care

Standardised mortality rates are used to compare local information on total mortality or mortality from specific causes

Morbidity:

National and local registers provide data of variable accuracy. Registers exist for cancers (type of cancer, treatment, and survival); drug addiction; congenital abnormalities; specific diseases (such as diabetes and stroke)

Communicable disease notification provides a source of information for local surveillance

The Royal College of General Practitioners collects morbidity data from sample practices around Britain

Prescribing data can be a valuable surrogate marker of morbidity

Insurance companies can be an important source of health information in countries with systems based largely on insurance

Health care:

Hospital activity data can provide information on hospital admissions, diagnoses, length of stay, operations performed, and patients’ characteristics

Clinical indicators such as the health service indicators, can provide information on the comparative performance of hospitals and health authorities

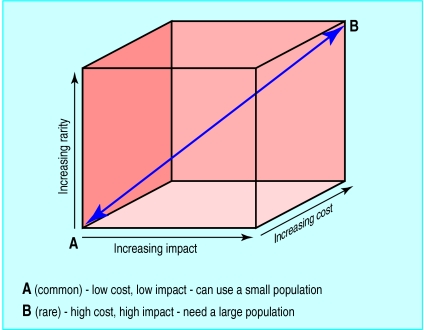

Three important issues need to be taken into account when deciding the minimum size of the population on which a needs assessment should be based: the frequency of occurrence (incidence, prevalence, or both); the impact of the condition on those who have it; and the cost implications of treatment.

For a rare condition with a high impact on patients and carers and with high treatment costs (childhood leukaemia, for example) a relatively large population needs to be studied for needs assessment to be worth while. The extent of need for common, low impact, low cost conditions can be assessed on smaller populations. For a single practice it would be unwise to assess need for conditions with a prevalence of less than 1%. So whereas a needs assessment for childhood leukaemia would be of limited value for a population of under one million, a needs assessment for mild depression could be based on the population served by a four doctor practice.

The NHS, in common with many other organisations, devotes more care and resources to collecting data than it does to using the data it collects. Routine reports of information are not as comprehensive in Britain as in some countries (such as Scandinavian countries) but they do exist, and it is surprising how infrequently they are used or even known about (box).

Unfortunately, “Murphy’s law of information” plays a part at this stage: “The information we have is not what we want. The information we want is not what we need. The information we need is too expensive to collect.” Despite that pessimistic view, routinely available data can be used, even if this entails some compromise in terms of precision. Used with survey information, routinely collected data can provide a powerful assessment of health needs and use of services (box).

Example of an epidemiological health needs assessment9

Objective: To assess whether the use of health services by people with coronary heart disease reflected need. Setting: Health authority with a population of 530 000. Methods: The prevalence of angina was determined by a validated postal questionnaire. Routine health data were collected on standardised mortality ratios; admission rates for coronary heart disease; and operation rates for angiography, angioplasty, and coronary heart disease. Census data were used to calculate Townsend scores to describe deprivation for electoral wards. Prevalence of angina and use of services were then compared with deprivation scores for each ward. Results: Angina and mortality from heart disease was more common in wards with high deprivation scores. Treatment by revascularisation procedures was more common in more affluent wards. Conclusion: The use of revascularisation services was not commensurate with need. Steps should be taken to ensure that health care is targeted at those who most need it.

Figure 4.

Attributes of a health problem that influence the size of the population for needs assessment

Figure.

These articles have been adapted from Health Needs Assessment in Practice, edited by John Wright, which will be published in July.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Bibby for his advice and comments and to Margaret Haigh and Pam Lilley for their secretarial support.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Wright J, Williams DRR, Wilkinson J. The development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ. 1998;316:1310–1313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7140.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens A, Raftery J. Health care needs assessment. Vol. 1. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994. Introduction; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Last JM. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. A dictionary of epidemiology. 3rd ed; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subcommittee of WHO/ISH Mild Hypertension Liaison Committee. Summary of 1993 World Health Organisation-International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of mild hypertension. BMJ. 1993;307:1541–1546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6918.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Asthma Education Program. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation Study Group. Diabetes mellitus. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1985;727. [PubMed]

- 7.Doyal L. Needs, rights and equity: moral quality in healthcare rationing. Qual Health Care. 1995;4:273–283. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.4.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams R. Diabetes. In: Stevens A, Raftery J, editors. Health care needs assessment. Vol. 1. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994. pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payne N, Saul C. Variations in use of cardiology services in a health authority: comparison of coronary artery revascularisation rates with prevalence of angina and coronary mortality. BMJ. 1997;314:257–261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]