Abstract

RNase E is an important regulatory enzyme that plays a key role in RNA processing and degradation in Escherichia coli. Internal cleavage by this endonuclease is accelerated by the presence of a monophosphate at the RNA 5′ end. Here we show that the preference of E. coli RNase E for 5′-monophosphorylated substrates is an intrinsic property of the catalytically active amino-terminal half of the enzyme and does not require the carboxy-terminal region. This property is shared by the related E. coli ribonuclease CafA (RNase G) and by a cyanobacterial RNase E homolog derived from Synechocystis, indicating that the 5′-end dependence of RNase E is a general characteristic of members of this ribonuclease family, including those from evolutionarily distant species. Although it is dispensable for 5′-end-dependent RNA cleavage, the carboxy-terminal half of RNase E significantly enhances the ability of this ribonuclease to autoregulate its synthesis in E. coli. Despite similarities in amino acid sequence and substrate specificity, CafA is unable to replace RNase E in sustaining E. coli cell growth or in regulating RNase E production, even when overproduced sixfold relative to wild-type RNase E levels.

The degradation of mRNA serves as an important genetic regulatory mechanism in all organisms. Within a single cell, mRNA lifetimes can differ by as much as 2 orders of magnitude. These differences directly affect both steady-state mRNA concentrations and the speed with which gene expression can be induced or repressed in response to environmental cues. Despite the importance of mRNA turnover for gene regulation, comparatively little is yet understood about the molecular mechanisms responsible for differences in mRNA longevity.

In prokaryotic organisms, mRNA degradation is accomplished by a combination of endonucleolytic cleavage and 3′ exonucleolytic digestion. The degradation of most mRNAs in Escherichia coli is thought to begin with internal cleavage by RNase E. This important endonuclease is essential for cell growth, and its inactivation has been shown to prolong the lifetime of bulk mRNA and to impede the processing and decay of a variety of individual transcripts (1, 2, 17, 20, 21, 27). RNase E is a large ribonuclease (1,061 amino acid residues) that exists in E. coli as a component of the RNA degradosome, a multienzyme RNA degradation complex that also contains a 3′ exoribonuclease (polynucleotide phosphorylase), an RNA helicase (RhlB), a glycolytic enzyme (enolase), and possibly other components (5, 18, 22). Previous studies have shown that the amino-terminal half of RNase E (amino acid residues 1 to 498) contains the active site for RNA cleavage and that this portion of the protein is essential for cell growth (14, 15). The carboxy-terminal half of RNase E (residues 499 to 1061) provides a scaffold for the assembly of the other degradosome components and contains an arginine-rich RNA-binding domain of unknown function (8, 14, 26, 28).

RNase E shows a preference for cleaving RNA within regions that are AU rich and single stranded (10, 16). Equally important in defining the substrate specificity of this endonuclease is its striking 5′-end dependence. In vitro experiments have shown that purified E. coli RNase E prefers to cleave RNAs that are monophosphorylated, rather than triphosphorylated, at the 5′ end (12). This property is somewhat surprising in view of the fact that RNA cleavage by this endonuclease typically occurs at a significant distance from the 5′ terminus, and the preference suggests that somewhere on RNase E there may be a site for recognizing and binding monophosphorylated RNA 5′ ends. Whether the ability to recognize the 5′ phosphorylation state of RNA is an intrinsic characteristic of the catalytic amino-terminal half of RNase E or a property conferred by the carboxy-terminal half of the protein is not known. Nor is it clear whether this property is peculiar to the E. coli enzyme or widely shared by homologous enzymes from distantly related species. In principle, the 5′-end dependence of RNase E would be expected to hasten further digestion of the 5′-monophosphorylated products of endonucleolytic cleavage, thereby enhancing the processivity of mRNA decay.

Another important property of RNase E is its ability to autoregulate its synthesis by controlling the degradation rate of its own mRNA (rne mRNA), whose longevity in E. coli varies inversely with cellular RNase E activity (6). Feedback inhibition of rne gene expression is mediated in cis by the rne 5′ untranslated region, which can confer this property onto heterologous reporter transcripts to which it is fused. The short lifetime of rne mRNA in E. coli and the unusual sensitivity of rne expression to cellular RNase E activity suggest that certain features of the 5′ untranslated region make the rne transcript particularly vulnerable to cleavage by RNase E.

To learn more about the biochemical mechanisms underlying the specificity of RNA cleavage by RNase E, we have begun to investigate the origin of its preference for 5′-monophosphorylated substrates and of its ability to autoregulate its synthesis. Our data indicate that the 5′-end dependence of RNase E maps to the amino-terminal half of the enzyme and that this property is shared by other proteins with sequence homology to this region of RNase E. Though dispensable for 5′-end-dependent cleavage, the carboxy-terminal half of the protein plays a key role in the mechanism of feedback regulation of RNase E synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and strains.

The isogenic E. coli K-12 strains CJ1827 (rne+) and CJ1828 (ams-1) are MC1061 derivatives that each contain a chromosomal copy of the rne-lacZ fusion ez1 (6). CJ1832 is another MC1061 derivative in which transcription of the rne gene has been placed under the control of a lac promoter and operator; the construction of this strain will be described elsewhere (C. Jain and J. G. Belasco, unpublished data). CJ1833 is identical to CJ1832 except that it contains a wild-type rne gene on the chromosome. Strains BL21(DE3) and BL21(DE3)-2 contain an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible gene encoding T7 RNA polymerase (11).

Plasmid pT7-R25, which was used as a template for the in vitro synthesis of RNA I.26, has previously been described (3). Plasmid pRNE1000 is a derivative of cloning vector pMPM-K1 (Kmr) (13) that directs the constitutive synthesis of a full-length amino-terminally tagged form of E. coli RNase E at a cellular concentration similar to that of wild-type RNase E encoded by the chromosomal rne gene. The 31 amino acids inserted after the N-terminal methionine residue (EKKAAAHHHHHHVAAEQKLISEEDLNGAARS) include a hexahistidine affinity tag and a c-Myc epitope tag. Transcription is driven by a modified IS10 promoter containing an up mutation in the −35 region (TGGATA → TTGATA). A T7 phage promoter lies upstream of the IS10 promoter. Plasmid pNRNE1000 encodes a tagged, truncated form of RNase E lacking the C-terminal 563 residues (N-RNase E). It was constructed by cleaving pRNE1000 with AflII, filling in the ends, and inserting a linker with stop codons in all three reading frames (CTAGTCTAGACTAG). Plasmid pCAFA1000 encodes an amino-terminally tagged form of E. coli CafA. It was constructed by replacing the pRNE1000 segment that encodes residues 2 to 1061 of RNase E with a DNA fragment that encodes all 495 residues of CafA. Plasmid pSYNRNE1000 encodes an amino-terminally tagged form of the RNase E homolog of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (GenBank accession no. D90899). The plasmid was constructed by replacing the pRNE1000 segment that encodes residues 2 to 1061 of RNase E with a DNA fragment that encodes all 674 residues of Synechocystis RNase E (SynRne). Plasmids pRNE2000 and pNRNE2000 are identical to pRNE1000 and pNRNE1000, respectively, except that ribonuclease synthesis is enhanced by an IS10 promoter mutation in the −10 region (TCAAAT → TAAAAT) instead of the −35 region. Plasmids pCAFA3000 and pSYNRNE3000 are identical to pCAFA1000 and pSYNRNE1000, except that protein synthesis is maximized by the presence of both the −10 and −35 promoter mutations. The fidelity of each plasmid construction was verified by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing.

Protein purification.

Purified Xrn1p was kindly provided by Arlen Johnson (University of Texas, Austin). Amino-terminally tagged forms of N-RNase E, CafA, and SynRne were produced by induction of T7 RNA polymerase in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) or BL21(DE3)-2 containing pNRNE1000, pCAFA1000, or pSYNRNE1000, respectively. Two to 3 h after adding IPTG (1 mM) to a log-phase culture (A600 = 0.5) grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, the cells were pelleted, resuspended in buffer A (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Genapol X-080), and lysed with a French press. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 20 min), and N-RNase E, CafA, and SynRne were purified from each of the resulting supernatants by affinity chromatography on a Ni-nitrilotriacetate column (Qiagen) eluted with an imidazole gradient (10 to 400 mM in buffer A). Peak fractions were pooled and further purified to near homogeneity by anion-exchange chromatography on an UNO-Q column (Bio-Rad) eluted with a salt gradient (50 to 600 mM NaCl in buffer A). The peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against buffer A, and the purified proteins were stored at −80°C. Protein samples were diluted just before their use in cleavage assays.

RNA synthesis, analysis, and cleavage.

Internally radiolabeled RNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. The reaction mixture (20 μl) contained Tris Cl (40 mM, pH 7.9), MgCl2 (6 mM), NaCl (10 mM), dithiothreitol (7.5 mM), spermidine (2 mM), GTP (0.25 mM), CTP (0.25 mM), UTP (0.25 mM), ATP (0.025 mM), [α-32P]ATP (30 μCi), GMP (0 or 15 mM), RNasin (20 U; Promega), plasmid pT7-R25 linearized by HindIII cleavage (0.2 μg), and T7 RNA polymerase (40 U). After incubation for 16 h at 37°C, the reaction mixture was diluted with water (30 μl) and the RNA was isolated by gel filtration on Sephadex G-50 and stored at −20°C. Capped RNA was synthesized under identical conditions, except that the cap analog m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G (2 mM) was used in place of GMP.

The suitability of these reaction conditions for synthesizing 5′-monophosphorylated or -capped RNA was confirmed in experiments involving the synthesis of RNA that was internally labeled with a fluorescent nucleotide analog and 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]GTP. Fluorescent RNA radiolabeled at the 5′ terminus was synthesized in a reaction mixture (20 μl) that contained Tris Cl (40 mM, pH 7.9), MgCl2 (6 mM), NaCl (10 mM), dithiothreitol (7.5 mM), spermidine (2 mM), GTP (0.25 mM), CTP (0.25 mM), UTP (0.075 mM), ATP (0.025 mM), fluorescein-12-UTP (0.25 mM), [γ-32P]GTP (30 μCi), GMP (0, 5, or 15 mM), RNasin (20 U; Promega), plasmid pT7-R25 linearized by HindIII cleavage (0.2 μg), and T7 RNA polymerase (40 U). After incubation for 16 h at 37°C, the reaction mixture was diluted with water (30 μl) and the RNA was isolated by gel filtration on Sephadex G-50. RNA samples synthesized at various GMP/GTP ratios were subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and analyzed for radioactivity and fluorescence with a Molecular Dynamics Storm 820 PhosphorImager and a Molecular Dynamics 575 FluorImager, respectively. The relative radioactivity of the samples (C) was 1 (GMP/GTP ratio = 0:1), 0.339 (GMP/GTP ratio = 20:1), or 0.095 (GMP/GTP ratio = 60:1). The relative fluorescence of the samples (F) was 1 (GMP/GTP ratio = 0:1), 1.71 (GMP/GTP ratio = 20:1), or 1.04 (GMP/GTP ratio = 60:1). From these values, the percentage of 5′-monophosphorylated RNA (1 − C/F) was calculated to be 0% (GMP/GTP ratio = 0:1), 80% (GMP/GTP ratio = 20:1), or 91% (GMP/GTP ratio = 60:1). Similar experiments with fluorescently labeled RNA indicated that the reaction conditions used for capped RNA synthesis [2 mM m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G instead of GMP] yielded products that were more than 90% capped.

RNA cleavage with N-RNase E, CafA, SynRne, or Xrn1p was carried out at 30°C with a reaction mixture (35 μl) containing Tris Cl (25 mM, pH 7.5), MgCl2 (10 mM), KCl (60 mM), NH4Cl (100 mM), dithiothreitol (0.1 mM), glycerol (5% [vol/vol]), RNA I.26 (3 pmol [50 pmol in assays of SynRne]), and ribonuclease (0.14 pmol of N-RNase E, 0.14 pmol of CafA, 3.4 pmol of SynRne, or 0.25 pmol of Xrn1p). Reaction samples (5 μl) were removed at different time intervals and quenched by the addition of 15 μl of loading buffer (22 mM Tris borate [pH 7.5], 4 mM EDTA, 90% formamide, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue). After denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. Radioactive gel bands were visualized and quantitated on a Molecular Dynamics Storm 820 PhosphorImager.

Complementation and rne-lacZ repression in E. coli.

The ability of various proteins to compensate for the absence of wild-type RNase E production in E. coli was assessed by introducing plasmids that encode these proteins into CJ1832, an E. coli strain in which transcription of the chromosomal RNase E gene is IPTG dependent. After several generations of growth in the presence of IPTG (1 mM), the cells were plated on LB agar lacking IPTG so that their ability to grow into colonies in the absence of RNase E could be judged. Expression of the rne-lacZ reporter ez1 in the Δlac host strains CJ1827 and CJ1828 was measured by performing β-galactosidase assays on extracts prepared from log-phase cultures grown at 37°C in LB medium, as previously described (6).

The relative concentrations of plasmid-encoded RNase E, N-RNase E, CafA, and SynRne in CJ1828 cells containing pRNE1000, pRNE2000, pNRNE1000, pNRNE2000, pCAFA3000, or pSYNRNE3000 were determined by immunoblot analysis with monoclonal anti-Myc antibodies (Zymed). The relative concentration of plasmid-encoded RNase E in CJ1832 cells containing pRNE1000 or pRNE2000 was compared to the concentration of chromosomally encoded wild-type RNase E in isogenic CJ1833 cells by immunoblot analysis with polyclonal anti-RNase E antibodies. In each case, cultures were grown to log phase at 37°C in LB medium lacking IPTG, and cell extracts were prepared by heating culture samples to 100°C for 7 min in loading buffer (62 mM Tris Cl [pH 6.8], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% glycerol, 0.001% bromophenol blue). After assaying for total cellular protein (24), equal amounts of each sample (10 μg) were fractionated by electrophoresis on an SDS–6% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham). Gel bands were visualized and quantitated with anti-Myc or anti-RNase E antibodies, a Vistra-enhanced chemifluorescence kit (Amersham), and a Molecular Dynamics 575 FluorImager.

RESULTS

5′-end-dependent cleavage of RNA by the amino-terminal half of E. coli RNase E.

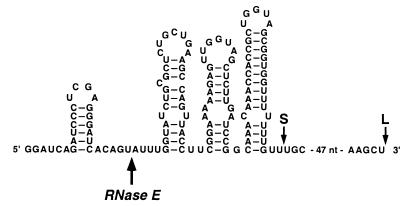

To begin to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the 5′-end dependence of RNase E, we decided to investigate whether the ability of this enzyme to distinguish the 5′ phosphorylation state of its substrates is an intrinsic characteristic of the catalytically active N-terminal half of the protein or whether the observed substrate preference also requires the C-terminal region, which contains an arginine-rich RNA-binding domain of unknown function. For this purpose, we overproduced and purified a truncated form of RNase E (N-RNase E) comprising the N-terminal 498 residues of the enzyme preceded by a hexahistidine affinity tag and a c-Myc epitope tag. As a model substrate, we chose a derivative of RNA I, an untranslated regulatory RNA that controls the replication of ColE1-type plasmids such as pBR322. In E. coli and in vitro, RNase E cleaves RNA I at an internal site 5 nucleotides from the 5′ end. RNA I.26 is an extended version of RNA I that carries 22 additional nucleotides at the 5′ end and up to 55 additional nucleotides at the 3′ end (Fig. 1). Except for one extra 5′-terminal nucleotide and some heterogeneity at the 3′ end (see below), RNA I.26 closely resembles another RNA I derivative (RNA I.25) previously shown to be cleaved by RNase E in E. coli at the same site and at the same rate as wild-type RNA I (3). RNA I.26 was synthesized in vitro by transcription of a DNA template with T7 RNA polymerase. Two RNA products were obtained, a long runoff transcript ending at the terminus of the DNA template (RNA I.26-L) and a shorter transcript ending at a natural termination site near the 3′ end of wild-type RNA I (RNA I.26-S) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

RNA I.26. The sequence and secondary structure of RNA I.26 are shown, except for 47 nucleotides (AAGCAGCAGAUUACGGGGGAUCCUCUAGAGUCGACCUGCAGGCAUGC) near the 3′ terminus. The secondary structure of RNA I.26 and that of the closely related transcript RNA I were determined previously by chemical alkylation and ribonuclease sensitivity (3, 19, 25). The primary site of RNase E cleavage is marked. Synthesis of RNA I.26 by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase generates two RNA products, the long runoff transcript (RNA I.26-L) shown (L) and a shorter transcript (RNA I.26-S) whose approximate 3′ end is indicated (S). nt, nucleotides.

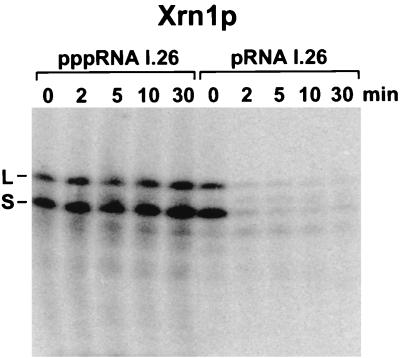

To assess whether cleavage by the N-terminal half of RNase E is 5′ end dependent, it was necessary to compare the cleavage rates of RNAs that differed only in their 5′ phosphorylation state, one beginning with a 5′-terminal triphosphate and the other with a 5′-terminal monophosphate. Due to the lack of a convenient existing procedure for synthesizing 5′-monophosphorylated RNAs, we developed a new method for this purpose. As usual, the triphosphorylated substrate (pppRNA I.26) was prepared by in vitro transcription in the presence of all four nucleoside triphosphates, whereas the reaction mixture for the in vitro synthesis of the monophosphorylated substrate (pRNA I.26) contained in addition a large excess of GMP (GMP/GTP = 60) for incorporation at the RNA 5′ end. Two experiments were performed to compare the phosphorylation state of the 5′ ends of pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26. First, when these two RNAs were synthesized from a nucleotide mixture containing [γ-32P]GTP and fluorescein-labeled UTP, the ratio of radioactivity to fluorescence in the RNA products indicated ∼91% monophosphorylation of the pRNA I.26 sample (see Materials and Methods). In a second experiment, the monophosphorylated and triphosphorylated substrates were internally radiolabeled by synthesis in the presence of [α-32P]ATP and then treated with the yeast 5′ exonuclease Xrn1p (Fig. 2), which preferentially degrades RNAs beginning with a 5′ monophosphate rather than a 5′ triphosphate (23). Digestion of pRNA I.26 with this exonuclease proceeded more than 100 times faster than digestion of pppRNA I.26. Together, these analyses indicate that monophosphorylated RNAs can readily be synthesized by in vitro transcription in the presence of excess GMP.

FIG. 2.

Digestion of pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26 by Xrn1p. Internally radiolabeled pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26 (3 pmol) were treated with equal amounts of purified Xrn1p (0.25 pmol). Reaction samples were quenched at time intervals with EDTA and analyzed by electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands corresponding to the long (L) and short (S) forms of RNA I.26 are marked.

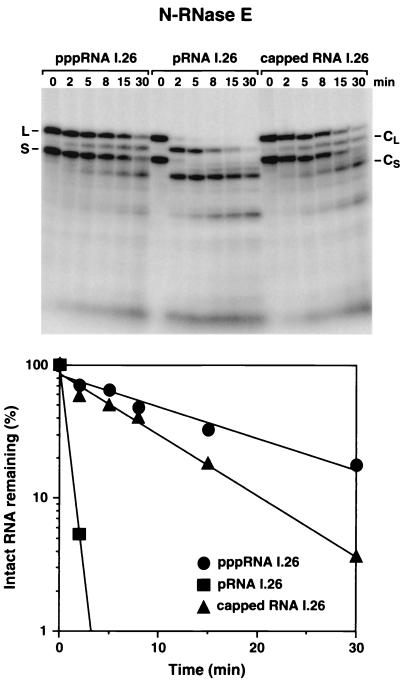

Like Xrn1p, the N-terminal half of RNase E showed a marked preference for the monophosphorylated substrate. Endonucleolytic cleavage of internally radiolabeled pRNA I.26 by N-RNase E was 25- to 30-fold faster than cleavage of pppRNA I.26 (Fig. 3), a rate acceleration comparable in magnitude to that observed for RNA cleavage by the full-length enzyme (12). A similar differential rate of cleavage by N-RNase E was observed in an internally controlled experiment in which the monophosphorylated and triphosphorylated substrates were combined in a 2:1 ratio; digestion of this RNA mixture was biphasic, with ∼65% of the substrate cleaved rapidly and ∼35% cleaved slowly (data not shown). In each case, initial cleavage of RNA I.26 occurred at a site ∼27 nucleotides from the 5′ end, corresponding to the site where RNase E cleaves wild-type RNA I and RNA I.25 in E. coli (Fig. 1) (3). Prolonged treatment with N-RNase E resulted in further cleavage at secondary sites. No cleavage was observed when N-RNase E was omitted from the reaction mixture (data not shown). These findings indicate that the 5′-end dependence of RNA cleavage by RNase E is a property of the amino-terminal half of this endonuclease.

FIG. 3.

Digestion of pppRNA I.26, pRNA I.26, and capped RNA I.26 by N-RNase E. Internally radiolabeled pppRNA I.26, pRNA I.26, and m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-capped RNA I.26 (3 pmol) were treated with equal amounts of purified N-RNase E (0.14 pmol). Reaction samples were quenched at different time intervals with EDTA and analyzed by electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands corresponding to the long (L) and short (S) forms of RNA I.26 are marked, as are their respective primary cleavage products (CL and CS) lacking an ∼27-nucleotide 5′-terminal fragment. Beneath the autoradiogram is a semilogarithmic plot of intact RNA remaining (RNA I.26-L plus RNA I.26-S) versus time for each of the three substrates. Best-fit lines were calculated by linear regression analysis. The relative cleavage rate of the three RNA substrates was 27:1:2 (monophosphorylated:triphosphorylated:capped).

The simplest explanation for the preferential cleavage of monophosphorylated RNAs by N-RNase E is that this portion of the enzyme may contain a binding site for monophosphorylated RNA 5′ termini. This 5′-end binding site might be entirely distinct from the active site that catalyzes internal RNA cleavage. Thus, the overall cleavage rate of an RNA may reflect the combined affinity of its 5′ end and its internal cleavage site(s) for the enzyme. In principle, the slow cleavage of triphosphorylated RNAs could result either from weaker binding of their 5′ termini to the same enzyme pocket that binds monophosphorylated 5′ ends or from a failure of their 5′ termini to bind at all to RNase E. To distinguish these possibilities, we compared the cleavage rate of pppRNA I.26 with that of a 5′-capped form of RNA I.26. The m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G cap structure characteristic of eukaryotic mRNAs comprises an inverted nucleotide joined to the RNA 5′ end via a 5′-5′ phosphoanhydride linkage. A cap would be expected to render the 5′ terminus unrecognizable to proteins of bacterial origin by masking it with a structure that, in effect, resembles a second 3′-terminal nucleotide. Nonetheless, capped RNA I.26 was cleaved by N-RNase E at a rate no slower than that of pppRNA I.26 (Fig. 3). We conclude that RNase E is able to cleave substrates that lack a recognizable 5′ end and that the low rate of cleavage of pppRNA I.26 does not contain any detectable kinetic component that could be attributed to recognition of its triphosphorylated 5′ terminus by the enzyme.

RNA cleavage by Synechocystis RNase E and E. coli CafA.

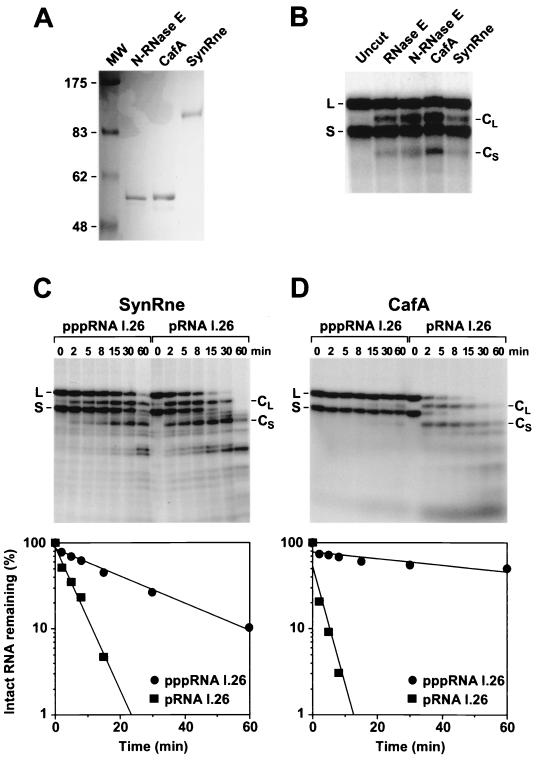

Sequence homologs of E. coli RNase E are found in a variety of prokaryotic organisms (7). Typically, the strongest homology is to the amino-terminal region of the E. coli protein (amino acid residues 1 to 413). For example, the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 produces a protein (GenBank accession no. D90899) whose N-terminal region (residues 1 to 406) is 35% identical to the corresponding portion of E. coli RNase E, and E. coli itself contains a second protein, CafA, whose N-terminal region (residues 1 to 420) shares 36% identity with the amino-terminal portion of RNase E. Purified Synechocystis RNase E (SynRne) has been shown to possess endoribonuclease activity and to cleave 9S RNA and RNA I in vitro at sites similar to those cleaved by E. coli RNase E (7). Likewise, recent studies with E. coli have indicated that disruption of the cafA gene affects 16S rRNA processing, suggesting that this protein too has ribonuclease activity and prompting proposals that it be renamed RNase G (9, 30).

The sequence similarity of SynRne and CafA to the amino-terminal half of RNase E raised the possibility that endonucleolytic cleavage by these RNase E homologs might be 5′ end dependent. To address this question, each of these proteins was overproduced in E. coli and purified (Fig. 4A) so that the rate at which it cleaved monophosphorylated versus triphosphorylated RNA I.26 could be compared. Both SynRne and CafA cleaved RNA I.26 at or near the previously defined RNase E cleavage site (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that purified CafA indeed has endonuclease activity and validating the designation of this protein as a ribonuclease (RNase G). Moreover, like E. coli RNase E, SynRne and CafA both showed a marked preference for the monophosphorylated substrate (Fig. 4C and D), cleaving it 5 to 6 times (SynRne) to more than 25 times (CafA) faster than they cleaved triphosphorylated RNA I.26. These data suggest that the 5′-end dependence of RNase E is a property that is evolutionarily well conserved among RNase E homologs, including those of distantly related species.

FIG. 4.

Digestion of pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26 by CafA and SynRne. (A) Purified N-RNase E, CafA, and SynRne were examined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis beside a set of protein molecular weight standards (lane MW). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Calibration is in kilodaltons. The calculated sizes of these amino-terminally tagged proteins are 57.3 kDa for N-RNase E, 58.9 kDa for CafA, and 78.5 kDa for SynRne. The electrophoretic mobility of SynRne is known to be anomalously slow (7). (B) The primary cleavage products (CL and CS) generated by treating pRNA I.26 with full-length RNase E, N-RNase E, CafA, or SynRne were compared by electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel beside uncut pRNA I.26 (L and S). (C) Internally radiolabeled pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26 (50 pmol) were treated with purified SynRne (3.4 pmol). Reaction samples were quenched at different time intervals with EDTA and analyzed by electrophoresis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands corresponding to the long (L) and short (S) forms of RNA I.26 are marked, as are their respective primary cleavage products (CL and CS) lacking a 5′-terminal fragment. Beneath the autoradiogram is a semilogarithmic plot of intact RNA remaining (RNA I.26-L plus RNA I.26-S) versus time for each of the two substrates. (D) Internally radiolabeled pppRNA I.26 and pRNA I.26 (3 pmol) were treated with purified CafA (0.14 pmol), and reaction samples were quenched at time intervals and analyzed as described for panel C. Beneath the autoradiogram is a semilogarithmic plot of intact RNA remaining (RNA I.26-L plus RNA I.26-S) versus time.

Complementation of RNase E deficiency and feedback regulation of RNase E synthesis.

In view of the these findings, we decided to investigate whether the amino-terminal half of E. coli RNase E is alone sufficient to mediate other important properties of the enzyme and whether SynRne and CafA share these properties. First, we examined whether N-RNase E is as effective as the full-length protein in supporting E. coli cell growth when present at a comparable cellular concentration. For this purpose, we made use of an E. coli strain (CJ1832) bearing a repressible RNase E (rne) gene. Normally, this strain is entirely dependent on IPTG for RNase E production and cell growth because expression of the endogenous rne gene has been placed under the control of a lac promoter. In the absence of IPTG, growth of CJ1832 can be rescued by introducing a plasmid (pRNE1000) from which full-length E. coli RNase E is expressed at wild-type levels in an epitope-tagged form. Unlike the full-length protein, epitope-tagged N-RNase E fails to restore growth when produced at up to three times the concentration of wild-type RNase E (pNRNE1000) but does restore cell growth when expressed at eight times wild-type RNase E levels (pNRNE2000).

The inability of cafA+ E. coli cells such as CJ1832 to grow in the absence of RNase E does not resolve whether CafA is capable of replacing RNase E in sustaining cell growth. This uncertainty results from a lack of information as to the cellular concentration of CafA, which makes it impossible to know whether the growth defect in the absence of RNase E is due to an inability of CafA to substitute functionally for RNase E or merely due to an inadequate supply of CafA. This is an important distinction in view of the failure of wild-type RNase E itself to sustain cell growth when produced in CJ1832 at less than 10% of its normal cellular concentration (C. Jain and J. Belasco, unpublished data).

To determine whether CafA and SynRne can functionally substitute for RNase E when present at a comparable concentration, plasmids encoding epitope-tagged forms of these proteins were tested for their ability to restore growth of CJ1832 in the absence of IPTG. Whereas SynRne sustains cell growth when expressed at the same concentration as wild-type RNase E (pSYNRNE3000), CafA cannot replace E. coli RNase E in supporting cell growth even when overproduced approximately sixfold relative to wild-type RNase E levels (pCAFA3000). It is not likely that the inviability of CJ1832 cells containing plasmid pCAFA3000 results from any hypothetical lethal effect of CafA at these levels, as the same cells grow normally when RNase E production is induced with IPTG.

Another important property of E. coli RNase E is its ability to autoregulate its synthesis by a feedback repression mechanism that controls the degradation rate of its own mRNA and of heterologous reporter transcripts to which the rne 5′ untranslated region has been fused (6). For example, β-galactosidase production from the rne-lacZ gene fusion ez1 is very sensitive to the level of RNase E activity in E. coli. To determine whether the amino-terminal half of RNase E is alone sufficient to mediate feedback regulation and whether SynRne and CafA share this ability to control expression of the E. coli rne gene, we introduced plasmids encoding epitope-tagged forms of E. coli RNase E, N-RNase E, SynRne, or CafA into an E. coli strain (CJ1828) bearing an ez1 reporter and a mutant rne allele (ams-1) on its chromosome. The ams-1 allele encodes a mutated form of RNase E that supports growth at 37°C but that is severely impaired in its ability to repress ez1 gene expression (6). β-Galactosidase assays were then performed on cell extracts to measure the reduction in ez1 expression that results from introducing each plasmid and its encoded ribonuclease into CJ1828. From these repression ratios and the relative cellular concentration of the plasmid-encoded ribonucleases (as determined by immunoblot analysis), we calculated a parameter that is a measure of each protein's regulatory activity (Table 1). Whereas full-length RNase E was very effective at reducing expression of the rne-lacZ reporter, the truncation variant N-RNase E was only ∼3% as potent, and SynRne and CafA exhibited little, if any, repressing activity. These findings indicate that the C-terminal half of RNase E is very important for efficient feedback regulation of rne gene expression. Consequently, the ineffectiveness of SynRne and CafA at regulating rne-lacZ expression may be due, at least in part, to their lack of a region homologous to this portion of RNase E.

TABLE 1.

Repression of rne-lacZ expression by RNase E-related proteins

| Proteina | Strainb | β-Galactosidase activity (U)c | Repression ratiod | Relative protein concentratione | Relative specific activityf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | CJ1828/pMPM-K1 | 1,224 ± 117 | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Wild-type RNase E | CJ1827 | 255 ± 21 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 1 | 0.70 ± 0.19 |

| RNase E | CJ1828/pRNE1000 | 288 ± 53 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 1.16 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.14 |

| RNase E | CJ1828/pRNE2000 | 101 ± 7 | 12.1 ± 1.5 | 2.04 ± 0.01 | 1 |

| N-RNase E | CJ1828/pNRNE2000 | 541 ± 91 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 1.1 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| CafA | CJ1828/pCAFA3000 | 1,018 ± 216 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| SynRne | CJ1828/pSYNRNE3000 | 928 ± 132 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.04 |

All proteins except wild-type RNase E were tagged at the amino terminus with the sequence MEKKAAAHHHHHHVAAEQKLISEEDLNGAARS.

E. coli K-12 strains CJ1827 and CJ1828 are isogenic rne+ and ams-1 derivatives of MC1061 that each bear a chromosomal rne-lacZ fusion (ez1). Plasmids pRNE1000, pRNE2000, pNRNE2000, pCAFA3000, and pSYNRNE3000 are derivatives of cloning vector pMPM-K1 (13) that each encode a tagged form of RNase E, N-RNase E, CafA, or SynRne.

The β-galactosidase activity of each strain provides a quantitative measure of the relative level of ez1 expression. The values reported are the averages of 6 to 15 independent measurements ± the standard deviations from these measurements.

To calculate the repression ratio, the β-galactosidase activity in CJ1828 cells containing the plasmid cloning vector pMPM-K1 (negative control) was divided by the β-galactosidase activity either in CJ1827 cells or in CJ1828 cells containing a plasmid that encodes an RNase E-related protein. Values are means ± standard deviations.

Relative protein concentrations were determined by immunoblot analysis of cell extracts, using anti-Myc antibodies. All values were normalized to the concentration of RNase E in CJ1827, which contains a single, wild-type rne gene on the chromosome. Because wild-type RNase E does not bind anti-Myc antibodies, its relative concentration in CJ1827 cells was estimated by using anti-RNase E antibodies to compare its abundance in CJ1833 cells to that of amino-terminally tagged RNase E in isogenic CJ1832 cells containing pRNE1000 or pRNE2000. The values reported are the averages of two to five independent measurements ± the standard deviations.

To a first approximation, the measured value for the specific activity of full-length RNase E is roughly proportional to its cellular concentration. Consistent with this observation are previous experiments with cells that produce wild-type RNase E at 1.0 or 2.8 times the normal concentration (6). This property makes it possible to estimate the relative specific activity of the various ribonucleases in repressing ez1 gene expression. Relative specific activity was calculated as being equal to (R − 1)/C, where R is the repression ratio and C is the relative protein concentration. (The numerator term is R − 1 rather than R because a repression ratio of 1 indicates a complete absence of repression.) The calculated specific activities were then normalized to that for full-length RNase E in CJ1828 cells containing pRNE2000. Values are means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

RNase E plays a key role in RNA processing and degradation in E. coli. Internal cleavage by this endonuclease is facilitated by the presence of a monophosphate group at the RNA 5′ end (12). Our data indicate that the preference of E. coli RNase E for 5′ monophosphorylated substrates is a property determined by the evolutionarily conserved amino-terminal half of the enzyme (residues 1 to 498). In contrast, the C-terminal half of RNase E (residues 499 to 1061), which is poorly conserved, is dispensable for 5′-end-dependent cleavage despite the presence there of an arginine-rich RNA- binding domain. Apparently, this arginine-rich domain is not required for 5′-end recognition. Though not involved in 5′-end-dependent RNA cleavage, the carboxy-terminal half of RNase E is crucial for efficient feedback regulation of RNase E synthesis.

Our studies of E. coli CafA (RNase G) and the cyanobacterial RNase E homolog SynRne show that the 5′-end dependence of E. coli RNase E is shared by other members of this ribonuclease family, including those from evolutionarily distant species. We conclude that the preference of RNase E and its homologs for substrates bearing a 5′ monophosphate is determined by conserved features of the N-terminal region of each enzyme, some of which presumably form a pocket for binding monophosphorylated RNA 5′ ends. Among the three proteins examined in this study, the regions of greatest sequence homology correspond to residues 40 to 68, 90 to 131, 165 to 170, 287 to 350, and 382 to 413 of E. coli RNase E and include a putative RNA-binding domain related in sequence to a domain present in ribosomal protein S1 and several other proteins that bind RNA (4).

Although it prefers monophosphorylated substrates, E. coli RNase E is nonetheless capable of slowly cleaving RNAs that bear a 5′ triphosphate. The ability of RNase E to cut triphosphorylated RNAs does not seem to involve recognition of the 5′ terminus, as a capped RNA lacking a recognizable 5′ end is cleaved at the same rate. Thus, the rate of endonucleolytic cleavage by RNase E appears to have two components: (i) a 5′-end-independent basal rate that presumably reflects the intrinsic susceptibility of an internal RNA site to binding and cleavage at the enzyme active site and (ii) a rate acceleration that can result from the presence of a monophosphate at the 5′ end.

Though not essential for viability, the C-terminal half of RNase E markedly enhances the ability of the enzyme to autoregulate its synthesis and to perform other functions important for cell growth. As a consequence, N-RNase E is only 3% as effective as the full-length protein at repressing expression of an rne-lacZ reporter and must be produced at higher levels to sustain growth. Despite its importance for efficient feedback regulation, the C-terminal half of RNase E is not capable of carrying out this function on its own, as missense mutations or deletions within the amino-terminal half of the protein can abolish the ability of RNase E to repress rne-lacZ expression (6). Together, these findings indicate that the RNA cleavage activity of RNase E is not alone sufficient for efficient feedback regulation, which also depends upon the participation of the C-terminal half of the protein. The mechanism by which the C-terminal half of RNase E contributes to autoregulation and cell growth is not known, but other studies have indicated that this portion of the enzyme contains an arginine-rich RNA-binding domain and serves as a scaffold for the assembly of the other degradosome components (8, 14, 28). In principle, either of these features might enhance the efficiency of mRNA degradation in E. coli, which on average is half as fast in cells that produce only a truncated form of RNase E lacking the C-terminal region (11).

The reduced autoregulatory efficiency of N-RNase E may explain a previous report that an E. coli strain with a nonsense mutation at codon 593 of the chromosomal rne gene is viable despite the loss of the C-terminal half of RNase E (8). Most likely, the truncated form of RNase E encoded by this strain has a diminished capacity to effect feedback regulation and therefore is overproduced, compensating for the impediment to growth that would otherwise be expected. Likewise, our earlier overestimate of the activity of the amino-terminal half of RNase E (residues 1 to 498) in rne-lacZ repression (6) was probably a result of the overproduction of the protein, which would have partially masked its attenuated efficacy.

Like E. coli RNase E, the sequence homolog CafA cleaves RNA in a 5′-end-dependent fashion, and both enzymes cut RNA I.26 at approximately the same place. These findings raise the possibility that RNase E and CafA might be functionally redundant in E. coli. However, our data show that, despite its similarity to RNase E, CafA is unable to replace RNase E in sustaining cell growth or in regulating rne gene expression, even when overproduced sixfold relative to wild-type RNase E levels. Taken together, these findings are consistent with the idea that CafA and RNase E have distinct, if somewhat overlapping, roles in E. coli. Consonant with this notion is the previous observation that CafA and RNase E catalyze different steps in the maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA in E. coli, yet each is capable of substituting for the other in this process, albeit with reduced efficiency and slightly altered cleavage-site specificity (9, 30). Further investigation will be needed to learn the full extent of CafA function in E. coli.

The preference of RNase E and its homologs for 5′-monophosphorylated substrates may have important biological consequences. For example, this property would be expected to increase the processivity of mRNA degradation by accelerating further digestion of 5′-monophosphorylated intermediates produced by endonucleolytic cleavage of triphosphorylated primary transcripts. Such processivity may be important for minimizing the production of aberrant protein products from partially degraded mRNAs, and it would help to explain the frequent failure of degradation intermediates to accumulate significantly during mRNA decay (29). The effect of 5′ phosphorylation on RNA cleavage by members of this ribonuclease family may also be important for ordering the sequence of processing events during RNA maturation, e.g., by delaying RNase E or CafA cleavage until after cleavage by another endonuclease has occurred. Additional study should reveal more fully the mechanism and consequences of the 5′-end dependence of RNase E and its homologs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Arlen Johnson for supplying purified Xrn1p, Li-How Chen and Ibuki Kimura for anti-RNase E antibodies, Masaaki Wachi for a plasmid clone of the cafA gene, Vladimir Kaberdin and Alexander von Gabain for clones of the SynRne gene, Chaitanya Jain for E. coli strains CJ1827, CJ1828, CJ1832, and CJ1833, and Marc Dreyfus for E. coli strain BL21(DE3)-2.

This research was supported by a grant to J.G.B. from the National Institutes of Health (GM35769).

REFERENCES

- 1.Apirion D. Isolation, genetic mapping, and some characterization of a mutation in Escherichia coli that affects the processing of ribonucleic acids. Genetics. 1978;90:659–671. doi: 10.1093/genetics/90.4.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babitzke P, Kushner S R. The Ams (altered mRNA stability) protein and ribonuclease E are encoded by the same structural gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet P, Belasco J G. Control of RNase E-mediated RNA degradation by 5′-terminal base pairing in E. coli. Nature. 1992;360:488–491. doi: 10.1038/360488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bycroft M, Hubbard T J, Proctor M, Freund S M, Murzin A G. The solution structure of the S1 RNA binding domain: a member of an ancient nucleic acid-binding fold. Cell. 1997;88:235–242. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpousis A J, Van Houwe G, Ehretsmann C, Krisch H M. Co-purification of E. coli RNase E and PNPase: evidence for a specific association between two enzymes important in RNA processing and degradation. Cell. 1994;76:889–900. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain C, Belasco J G. RNase E autoregulates its synthesis by controlling the degradation rate of its own mRNA in Escherichia coli: unusual sensitivity of the rne transcript to RNase E activity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:84–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaberdin V R, Miczak A, Jakobsen J S, Lin-Chao S, McDowall K J, von Gabain A. The endoribonucleolytic N-terminal half of Escherichia coli RNase E is evolutionarily conserved in Synechocystis sp. and other bacteria but not the C-terminal half, which is sufficient for degradosome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11637–11642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kido M, Yamanaka K, Mitani T, Niki H, Ogura T, Hiraga S. RNase E polypeptides lacking a carboxyl-terminal half suppress a mukB mutation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3917-3925.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Pandit S, Deutscher M P. RNase G (CafA protein) and RNase E are both required for the 5′ maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1999;18:2878–2885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin-Chao S, Wong T-T, McDowall K J, Cohen S N. Effects of nucleotide sequence on the specificity of rne-dependent and RNase E-mediated cleavages of RNA I encoded by the pBR322 plasmid. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10797–10803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez P J, Marchand I, Joyce S A, Dreyfus M. The C-terminal half of RNase E, which organizes the Escherichia coli degradosome, participates in mRNA degradation but not rRNA processing in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:188–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackie G A. Ribonuclease E is a 5′-end-dependent endonuclease. Nature. 1998;395:720–723. doi: 10.1038/27246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer M P. A new set of useful cloning and expression vectors derived from pBlueScript. Gene. 1995;163:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00389-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDowall K J, Cohen S N. The N-terminal domain of the rne gene product has RNase E activity and is non-overlapping with the arginine-rich RNA-binding site. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:349–355. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDowall K J, Hernandez R G, Lin-Chao S, Cohen S N. The ams-1 and rne-3071 temperature-sensitive mutations in the ams gene are in close proximity to each other and cause substitutions within a domain that resembles a product of the Escherichia coli mre locus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4245–4249. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4245-4249.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowall K J, Lin-Chao S, Cohen S N. A+U content rather than a particular nucleotide order determines the specificity of RNase E cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10790–10796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melefors Ö, von Gabain A. Genetic studies of cleavage-initiated mRNA decay and processing of ribosomal 9S RNA show that the Escherichia coli ams and rne loci are the same. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miczak A, Kaberdin V R, Wei C L, Lin-Chao S. Proteins associated with RNase E in a multicomponent ribonucleolytic complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3865–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita M, Oka A. The structure of a transcriptional unit on colicin E1 plasmid. Eur J Biochem. 1979;97:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mudd E A, Krisch H M, Higgins C F. RNase E, an endoribonuclease, has a general role in the chemical decay of E. coli mRNA: evidence that rne and ams are the same genetic locus. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2127–2135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono M, Kuwano M. A conditional lethal mutation in an Escherichia coli strain with a longer chemical lifetime of mRNA. J Mol Biol. 1979;129:343–357. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Py B, Higgins C F, Krisch H M, Carpousis A J. A DEAD-box RNA helicase in the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome. Nature. 1996;381:169–172. doi: 10.1038/381169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens A, Poole T L. 5′-exonuclease-2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: purification and features of ribonuclease activity with comparison to 5′-exonuclease-1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16063–16069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoscheck C M. Quantitation of protein. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:50–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82008-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamm J, Polisky B. Structural analysis of RNA molecules involved in plasmid copy number control. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6381–6397. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.18.6381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taraseviciene L, Bjork G R, Uhlin B E. Evidence for an RNA binding region in the Escherichia coli processing endoribonuclease RNase E. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26391–26398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taraseviciene L, Miczak A, Apirion D. The gene specifying RNase E (rne) and a gene affecting mRNA stability (ams) are the same gene. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:851–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanzo N F, Li Y-S, Py B, Blum E, Higgins C F, Raynal L C, Krisch H M, Carpousis A J. Ribonuclease E organizes the protein interactions in the Escherichia coli RNA degradosome. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2770–2781. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Gabain A, Belasco J G, Schottel J L, Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Decay of mRNA in Escherichia coli: investigation of the fate of specific segments of transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:653–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wachi M, Umitsuki G, Shimizu M, Takada A, Nagai K. Escherichia coli cafA gene encodes a novel RNase, designated as RNase G, involved in processing of the 5′ end of 16S rRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:483–488. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]