Abstract

The genomic diversity of nine strains of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO2031, NCDO763, MMS36, C2, LM0230, LM2301, and MG1363) was studied by macrorestriction enzyme analysis using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. These strains were considered adequate for the investigation of genomic plasticity because they have been described as belonging to the same genetic lineage. Comparison of ApaI and SmaI genome fingerprints of each strain revealed the presence of several macrorestriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs), despite a high degree of similarity of the generated restriction patterns. The physical map of the MG1363 chromosome was used to establish a genome map of the other strains and allocate the RFLPs to five regions. Southern hybridization analysis correlated the polymorphic regions with genetic events such as chromosomal inversion, integration of prophage DNA, and location of the transposon-like structures carrying conjugative factor or oligopeptide transport system.

Until recently, analysis of the general structure and the gene order of the chromosomes of prokaryotic cells was held back by the lack of genetic tools for mapping bacterial genomes. The introduction of physical methods for the construction of chromosome maps, such as the “top-down” approach using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), has had a large impact on the genome characterization of a wide range of bacteria (10, 16).

Comparative studies of genome maps at the interspecies level allow one to define a conserved global architecture for circular bacterial chromosomes: almost all bacterial chromosomes contain several ribosomal operons (rrn) that are transcribed divergently from the origin of replication (oriC), which appears to be located opposite the terminus site (terC). Comparisons of the genomes of bacteria that belong to the same or related genera provide useful data about the structural maintenance of the chromosome itself as well as about the maintenance and disruption of gene order during evolution. With the exception of Bacillus (8, 51) and, to a lesser extent, Leptospira (79), the genome organization is highly conserved for most bacteria, as observed for Escherichia coli and Salmonella (30, 40), Borrelia (9, 50), Haloferax (42), Mycobacterium (53, 54), Mycoplasma (25), Streptomyces (33), and Neisseria (15), although some rearrangements are present.

At the intraspecies or strain level, comparative analysis yields information on the macrodiversity (defined as the variability of gene arrangement or macrorestriction polymorphisms) of a particular organism. Studies have shown that the extent of chromosome rearrangement depends largely on the species studied. Genome rearrangement among strains of E. coli (2, 52), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (39), Clostridium perfringens (6), Streptococcus thermophilus (61), Mycoplasma galliseptum (70), Halobacterium salinarium (23), and Thermococcus thermophilus (67) is seen as minimal, despite the identification of inversions, insertions, deletions, and translocations of some regions. In contrast, a greater genomic diversity or a significant mosaic structure has been observed between strains of S. enterica serovar Typhi (41), Rhodobacter capsulatus (49), Bacillus cereus (7), Leptospira interrogans (79), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (59).

The next step in the analysis of genomic macrodiversity is the identification of the genetic events (homologous or site-specific recombination, insertion-excision, transposition, etc.) responsible for such macrodiversity and the DNA sequences (IS elements or other repetitive sequences, prophages, duplicated genes, etc.) involved in genome rearrangement. For this purpose, it is essential to compare the genomes of strains belonging to the same genetic lineage (isogenic strains). However, experimental data that associate PFGE-generated restriction polymorphisms with identified genetic events are available only for three gram-negative bacteria (E. coli [52], P. aeruginosa [60], and Neisseria gonorrhoeae [19]) and seven gram-positive bacteria. In lysogenized strains of Staphylococcus aureus (4, 65) and C. perfringens (5), restriction polymorphism was correlated with prophage integration, whereas in S. thermophilus (62), Bacillus subtilis (71), and B. cereus (27), small deletions mediated by homologous recombination between tandemly repeated rrn operons were observed. In Streptomyces lividans (58) and S. ambofaciens (32), large DNA amplifications and deletions involved homologous recombination between specific loci (AUD).

Lactococcus lactis is a gram-positive mesophilic bacterium that is extensively used as a starter culture in the manufacture of dairy products. The PFGE technique has been used for several studies on the genome of L. lactis for estimation of the genome size and genome fingerprinting (37, 43, 68), analysis of plasmid stability (76), and study of integration sites of transposon Tn917 derivatives (26). The chromosome maps of four independent lactococcal strains have been published to date: L. lactis subsp. lactis DL11 (73) and IL1403 (34) and L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 (35) and FG2 (12). The genome of strain IL1403 has been completely sequenced recently (3). Hybridization data (14) showed that these two subspecies have a nucleotide divergence of 20 to 30%, the same order of magnitude as that observed between E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Comparative genome analysis of the four strains at a physical level revealed a tight correlation in the position of restriction sites for the two L. lactis subsp. lactis strains but not for the L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains. In addition, no similarity was found between the two subspecies. At the genetic level, i.e., gene order, different rearrangements were observed. Intersubspecies comparison revealed a large inversion that covers nearly half of the chromosome (35), whereas there was translocation/inversion of four discrete regions between the two L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains (12). However, the order of genes within the rearranged segments is largely conserved. These studies were performed on genetically unrelated strains, and so it was not possible to identify the mechanisms which brought about these events.

To investigate the plasticity of the lactococcal genome, we initiated a comparative analysis of the genomes of nine strains belonging to the same genetic lineage. The L. lactis subsp. cremoris strain MG1363 (17) is a plasmid-free derivative of strain NCDO712, the ancestor of lactococcal strains NCDO763, NCDO505, NCDO2031, and C2 (13). Three other strains were also analyzed: MMS36, a recombination-deficient mutant of strain NCDO763 (1); strain LM0230, a plasmid-free derivative of strain NCDO2031 (46); and strain LM2301, a streptomycin-resistant mutant of strain LM0230 (75). These different strains constitute the most extensively studied group of lactococcal strains in genetic analysis and molecular biology. We recently demonstrated that one restriction polymorphism observed between the chromosomes of strains MG1363 and NCDO763 was associated with a single inversion of half of the chromosome (11).

In this study, we used combined PFGE and Southern hybridization to determine restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) among the nine lactococcal strains, to assign these RFLPs to particular regions of their genome, and to identify the genetic events that could be correlated with these genome rearrangements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

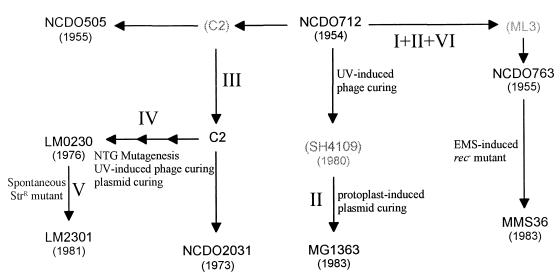

The genetic relationship between the L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains used in this study is presented in Fig. 1. Wild-type lactococcal strains were grown at 30°C in M17 broth (69). For the Lac− derivative strains LM0230, LM2301, and MG1363, the M17 broth was supplemented with 0.5% glucose (GM17 broth). When required, erythromycin was used at 5 μg/ml. Particles of temperate bacteriophages were obtained after UV induction of the lysogenic strain by the method of McKay and Baldwin (45).

FIG. 1.

Biological and genomic relationship of strains derived from L. lactis subsp. cremoris strain NCDO712. Parentheses indicate strains that were not included in this study. I, Inversion of half of the chromosome in regions 1 and 3; II, excision of the uncharacterized prophage in region 2; III, excision of the complete conjugative sex factor in region 5; IV, excision of the φT712 prophage in region 4; V, chromosomal deletion of a fragment containing the opp-pepO operon in region 3; VI, partial deletion of the conjugative sex factor in region 5. EMS, ethyl methanesulfonate; NTG, nitrosoguanidine; Str, streptomycin.

DNA manipulation.

Plasmid isolation, restriction digestion, ligation, and transformation in E. coli were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (63). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from either Boehringer Mannheim or New England Biolabs and used as recommended by the suppliers. DNA restriction fragments were purified from agarose gel using the Prep-A-Gene DNA purification kit (Bio-Rad). Lactococcus strains were transformed by electroporation (56), except that the cells were grown in GM17 supplemented with 2% glycine. Lactococcal genomic DNA used for PFGE analysis was purified and digested in agarose plugs as described previously (35). Bacteriophage DNA was extracted from phage particles by the method of Trautwetter et al. (72).

PFGE, determination of fragment sizes, and Southern hybridization.

PFGE were performed using a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field system (Pulsaphor Plus; LKB-Pharmacia) in 0.05 M TBE (1 M TBE is 1 M Tris base, 1 M boric acid, and 20 mM EDTA), as described previously (36). Restriction fragments were resolved under the following typical PFGE conditions: 2.5-s pulse time for 11 h for fragments of <100 kb, 7.5-s pulse time for 13 h for fragments of 100 to 300 kb, 15-s pulse time for fragments of 250 to 500 kb, and 30-s pulse time for fragments of 450 to 700 kb. Fragment sizes were determined manually by measurement of photographed gels. λ DNA concatemers, obtained using the procedure of Waterbury and Lane (77), were used for fragments larger than 48.5 kb. Smaller fragments were measured by comparison with a 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco-BRL). Southern hybridizations were done on dried agarose gels as described previously (35).

Estimation of the degree of genomic relatedness.

Similarity of restriction patterns was expressed using the Dice coefficient (SD) by the method of Grothues and Tümmler (22). The relatedness between two restriction patterns, A and B, is given by the ratio of twice the number of bands found in both patterns (nAB) to the sum of all bands in the two patterns (NA + NB): SD = 2nAB/(NA + NB). In our case, nAB, NA, and NB were obtained by summing the numbers of ApaI and SmaI restriction fragments. Strains were clustered by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) (66) using the Neighbor program (version 3.5c) of the PHYLIP package.

RESULTS

Restriction analysis of the L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains.

The physical map of the MG1363 chromosome (35) was constructed using the restriction endonucleases ApaI (GGGCCC), SmaI (CCCGGG), and NotI (GCGGCCGC) and the intron-encoded endonuclease I-CeuI (44). ApaI and SmaI generated a suitable number of restriction fragments and thus were used for the comparative study of the restriction patterns of the nine lactococcal strains. Visual inspection of ethidium bromide-stained PFGE gels showed that the chromosomal ApaI and SmaI fingerprints were very similar for these strains (Fig. 2A and B). For each strain, the size of every restriction fragment was estimated by direct comparison with restriction fragments of the MG1363 chromosome. In addition, the sizes of polymorphic restriction fragments were measured by comparison with DNA ladders. Depending on the strain, ApaI and SmaI endonucleases yielded a different number of restriction fragments (ranging from 39 to 45 and from 24 to 27, respectively), and the corresponding genome size was calculated by adding the sizes of every ApaI or SmaI restriction fragment (Table 1). The largest genome size difference was observed between strains NCDO712-NCDO505 and strain LM2301.

FIG. 2.

Macrorestriction patterns of L. lactis chromosomes. Lanes: 1, NCDO763; 2, MMS36; 3, NCDO712; 4, NCDO505; 5, NCDO2031; 6, C2; 7, LM2301; 8, LM0230; 9, MG1363; λ, lambda DNA concatemers. (A) ApaI digestion. Electrophoresis conditions were 7.5 s for 13.5 h. (B) SmaI digestion. In the upper panel, electrophoresis conditions for separation of the larger SmaI fragments were 15 s for 13.5 h. In the lower panels, electrophoresis conditions were 8 s for 13.5 h. (C) Dendogram of similarity values.

TABLE 1.

Sizes of polymorphic SmaI and ApaI restriction fragmentsa

| Fragment sizeb (kb) | Presence of fragment in strainc:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG1363d | NCDO712 | NCDO505 | NCDO763 | MMS36 | NCDO2031 | C2 | LM0230 | LM2301 | |

| SmaI fragments | |||||||||

| 610 | + (Sm1) | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 580 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 550 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 325 | + (Sm2) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 290 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 220 | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 180 | + (Sm5A) | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| 160 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 130 | + (Sm6) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| 105 | + (Sm8) | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| 58 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 55* | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 45 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 42 | + (Sm11A) | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| 36* | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 30* | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 24* | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| ApaI fragments | |||||||||

| 165 | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 160 | + (Ap3) | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| 145 | + (Ap4) | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 120 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| 100 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 75 | + (Ap10C) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 69 | + (Ap11) | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 67 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| 65 | + (Ap12B) | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 55* | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 49 | + (Ap14A) | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 29 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 19 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | + (Ap26) | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | + (Ap27B) | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 12 | + (Ap28) | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 11* | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

A detailed table containing the number and size of the ApaI and SmaI restriction fragments of each strain is available upon request to the authors.

Asterisks indicate fragments assigned to plasmid DNA (see text).

The mean genome size for a given strain was calculated assuming an error of the order of 5%: MG1363, 2.5 ± 0.1 Mb; NCDO712 and NCDO505, 2.6 ± 0.1 Mb; NCDO763 and MMS36, 2.6 ± 0.1 Mb; NCDO2031, 2.6 ± 0.1 Mb; C2, 2.6 ± 0.1 Mb; LM0230, 2.4 ± 0.1 M; LM2301, 2.4 ± 0.1 Mb.

Restriction fragments of strain MG1363 were labeled according to reference 35.

Strains were ordered according to the similarity of the ApaI and SmaI macrorestriction fragment patterns by cluster analysis (Fig. 2C). The high values of the Dice coefficient (SD), 0.81 to 1, reflect the close genomic relatedness between the nine strains studied. Two pairs of strains (NCDO712-NCDO505 and NCDO763-MMS36) gave indistinguishable fingerprints (SD = 1), suggesting that they have identical genome maps. In addition, the fingerprints of the NCDO2031 and C2 chromosomes were identical (SD = 0.986) except for a 3-kb size increase for one of the Sm11A fragments. On the basis of these results, the name NCDO712 is used in this report for both strains NCDO712 and NCDO505, the name NCDO763 is used for both strains NCDO763 and MMS36, and the name NCDO2031 is used for strains both NCDO2031 and C2 when referring to genome organization.

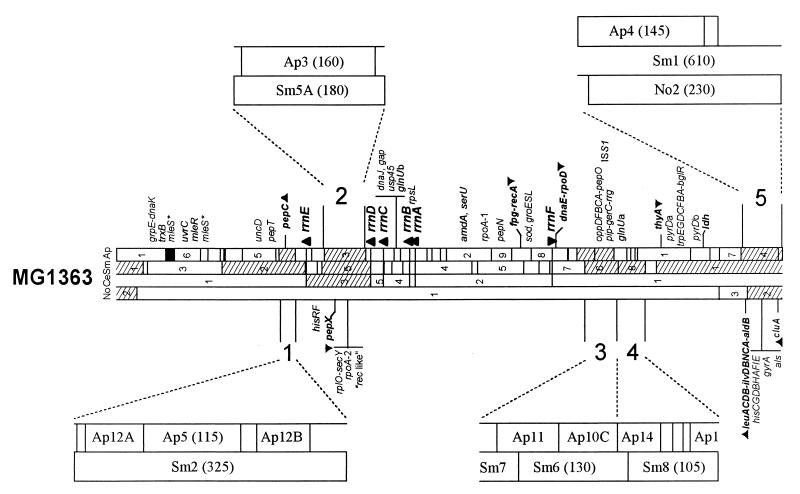

Identification of the polymorphic regions on the MG1363 chromosome.

Six SmaI fragments (Sm1, Sm2, Sm5A, Sm6, Sm8, and one of the Sm11 fragments) and nine ApaI fragments (Ap3, Ap4, one of the Ap10 fragments, Ap11, one of the Ap12 fragments, one of the Ap14 fragments, Ap26, one of the Ap27 fragments, and Ap28) present on the MG1363 chromosome were subjected to a size polymorphism in at least one fingerprint of the other strains (Table 1). Correlation of the location of these ApaI and SmaI fragments on the physical map of MG1363 chromosome allowed us to define five regions where genome rearrangements could account for the observed macrorestriction polymorphism (Fig. 3). Region 1 corresponds to the absence of fragments Sm2 and Ap12B on the NCDO763 chromosome. Region 2 corresponds to the absence of fragments Sm5A and Ap3 on the NCDO712 and NCDO2031 chromosomes. Region 3 corresponds to the absence of restriction fragments Sm6 and Ap11 on the NCDO763 chromosome and of Sm6, Ap10C, and Ap11 on the LM2301 chromosome. Region 4 corresponds to the absence of restriction fragments Sm8 and Ap14, Ap27, and Ap28 on the LM0230 and LM2301 chromosomes. Region 5 corresponds to the loss of fragments Sm1 and Ap4 on the NCDO763 chromosome and to the loss of Sm1, Ap4, and Ap26 fragments in strains NCDO2031, LM0230, and LM2301.

FIG. 3.

Locations of the five polymorphic regions of the MG1363 chromosome. Parentheses indicate the sizes (in kilobases) of the restriction fragments. The genome map of strain MG1363 is drawn according to Le Bourgeois et al. (35). Abbreviations; Sm, SmaI; Ap, ApaI; No, NotI; Ce, I-CeuI.

Correlation of genome rearrangements with singular genetic events.

The nine strains analyzed in this study have various genetic differences involving the presence of plasmid DNA and temperate bacteriophage (13, 46) or the location of conjugative sex factor (18, 47) and oligopeptide transport systems (74, 78). We made the assumption that these different genetic events would produce genome rearrangements large enough to be correlated with most of the RFLPs observed above. To characterize which genetic event(s) could be associated with the macrorestriction polymorphisms, each of the five regions was analyzed in more detail. We recently demonstrated that the macrorestriction polymorphism in regions 1 and 3 between the MG1363 and NCDO763 chromosomes was caused by the inversion of half of the chromosome in strain NCDO763 and was mediated by homologous recombination between two copies of an IS element (11). This inversion modified the size of two ApaI (Ap11 and Ap12B) and two SmaI (Sm2 and Sm6) fragments of the MG1363 chromosome, which were replaced, respectively, by 19- and 120-kb ApaI and 290- and 160-kb SmaI fragments on the NCDO763 chromosome.

(i) Identification of restriction fragments linked to plasmid DNA.

Strains NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO763, MMS36, NCDO2031, and C2 are known to contain plasmid DNA (13). All these strains contain a 55-kb lactose-protease (Lac-Prt) plasmid and some other cryptic plasmids. To assign particular restriction fragments to plasmid DNA, the following assumption was made: any additional fragment visualized only for this group of strains and not involved in genome rearrangements described in this study was considered to be plasmid DNA. An asterisk in Table 1 indicates the restriction fragments associated with plasmid DNA. Note that circular DNAs such as plasmids have a different electrophoretic mobility in PFGE from that of linear DNA molecules (24, 64). Plasmids in the open circular form (OC) do not migrate in PFGE whatever their size, whereas small covalently closed circular forms (CCC) migrate with anomalous mobility depending on the electrophoresis conditions. This indicates that a plasmid DNA will be visualized in PFGE only if be cut by restriction endonucleases.

Some restriction fragments were confirmed to be plasmid linked by hybridization using ISS1 as probe (Table 2). ISS1 was known to be present as one copy in the MG1363 chromosome, located on the Sm6 (130 kb) and Ap10C (75 kb) fragments (Fig. 3). This IS element was also found at two copies on the Lac-Prt plasmid of strain NCDO763 (55). Hybridization results showed that in addition to the Sm6 and Ap10C fragments revealed in all nine strains, one 55-kb ApaI fragment and one 55-kb SmaI fragment appeared on the NCDO712 and NCDO2031 fingerprints whereas only one 55-kb ApaI fragment appeared on the NCDO763 fingerprint. Furthermore, the 55-kb ApaI and SmaI fragments were unambiguously associated with the Lac-Prt plasmid by hybridization with the lacG gene (encoding the phospho-β-galactosidase of the Lac-Prt plasmid) as a probe (data not shown). The lack of the 55-kb SmaI hybridizing fragment in the NCDO763 fingerprint could be explained by the absence of the SmaI site from the Lac-Prt plasmid due to point mutation or a deletion too small to be seen by PFGE.

TABLE 2.

Sizes of hybridizing restriction fragments

| Probe used | Enzyme tested | Fragmenta (kb) | Presence of fragment in strainb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG1363 | NCDO712 | NCDO763 | NCDO2031 | LM0230 | LM2301 | |||

| ISS1 | SmaI | 130 [Sm6] | + | + | + (160) | + | + | + (105) |

| 55 | − | + | − | + | − | − | ||

| ApaI | 75 [Ap10C] | + | + | + | + | + | + (120) | |

| 55 | − | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| φT712 | SmaI | 220* [Sm4] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 180* [Sm5] | + | − | + | − | + | + | ||

| 105 [Sm8] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 22 [Sm14] | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| ApaI | 165* | − | + | − | + | − | − | |

| 160* [Ap3] | + | − | + | − | + | + | ||

| 49 [Ap14] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 13 [Ap27] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 12 [Ap28] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 33 [Ap19] | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Sm8 | SmaI | 105 [Sm8] | + | + | + | + | + (58) | + (58) |

| ApaI | 205 [Ap1] | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 49 [Ap14A] | + | + | + | + | + (29) | + (29) | ||

| 13 [Ap27B] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 12 [Ap28] | + | + | + | + | − | − | ||

| 8 [Ap29] | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Ap3 | SmaI | 180 [Sm5A] | + | + (220) | + | + (220) | + | + |

| ApaI | 160 [Ap3] | + | + (165) | + | + (165) | + | + | |

| No2 | NotI | 230 [No2] | + | + | + (200) | + (175) | + (175) | + (175) |

| SmaI | 610 [Sm1] | + | + | + (580) | + (550) | + (550) | + (550) | |

| ApaI | 205 [Ap1] | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 145 [Ap4] | + | + | + (120) | + (100) | + (100) | + (100) | ||

| 16 [Ap26] | + | + | + | − | − | − | ||

| 5′-cluA | SmaI | 610 [Sm1] | + | + | + (580) | − | − | − |

| ApaI | 50* | + | + | + (25) | − | − | − | |

| 16 [Ap26] | + | + | + | − | − | − | ||

| 5′-oppD | SmaI | 130 [Sm6] | + | + | + (160) | + | + | − |

| 55 | − | + | − | + | + | − | ||

| ApaI | 75 [Ap10C] | + | + | + | + | + | − | |

| 69* [Ap11] | + | + | + (19) | + | + (67) | − | ||

| 55 | − | + | − | + | + (65) | − | ||

| oppFBc | SmaI | 130 [Sm6] | + | + | + (160) | + | + | − |

| 55 | − | + | − | + | + (58) | − | ||

| ApaI | 75 [Ap10C] | + | + | + | + | + | − | |

| 55 | − | + | − | + | + (65) | − | ||

Fragment names are given in brackets. Asterisks indicate a weak hybridization signal. Sizes different from the size given in this column are shown in parentheses.

NCDO712 refers to NCDO712 and NCDO505 genomes; NCDO763 refers to NCDO763 and MMS36 genomes; and NCDO2031 refers to NCDO2031 and C2 genomes.

Probes oppCA and pepO gave the same hybridization pattern as oppFB.

(ii) Effect of the lysogenic status of strains on the macrorestriction polymorphism.

Strains NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO2031, and C2 are known to be lysogenic for a temperate bacteriophage (respectively named φT712, φT505, φT2031, and φTC2), but strain NCDO763 is not (13). In addition, strain MG1363 was obtained from a UV-induced prophage-free derivative of NCDO712 (17) and strain LM0230 is a spontaneous prophage-cured mutant obtained by nitrosoguanidine treatment of strain C2 (46). HindIII and PstI restriction enzyme analysis of the φT712, φT505, φT2031, and φTC2 genomes revealed an identical restriction pattern (data not shown), strongly suggesting that the four phages were very closely related. In addition, their genome contains two ApaI sites but no SmaI site. The genome size of φT712 was estimated to be 45 kb. When hybridized to the genomes of the nine strains, the entire phage DNA gave multiple signals of variable intensities (Table 2). By using different PstI restriction fragments of φT712 as more specific probes, we found that one SmaI fragment (Sm6) and three ApaI fragments (Ap14A, Ap27, and Ap28) of strains NCDO712, NCDO763, NCDO2031, and MG1363 contained the prophage DNA. In contrast, the genomes of strains LM0230 and LM2301 lacked the entire φT712 prophage DNA. The remaining hybridizing fragments (i.e., 165- or 160-kb and 33-kb ApaI fragments and 220-, 180-, and 22-kb SmaI fragments) were presumed to contain sequences that have weak homology to the φT712 DNA. The size of the deletion generated by the excision of φT712 prophage DNA was confirmed by performing Southern hybridizations using the Sm8 (105-kb) fragment from MG1363 chromosome as a probe (Table 2). This fragment strongly hybridized with the 105-kb SmaI fragment in all strains except for strains LM0230 and LM2301, where a 58-kb fragment was revealed. For ApaI fingerprints, the probe strongly hybridized with five fragments in all strains except LM0230 and LM2301, where only three fragments of 205, 29, and 8 kb were observed.

Another macrorestriction polymorphism that correlates better with the lysogenic status of the strain is the presence of two 220- and one 180-kb SmaI fragments on the genome of lysogenic strains NCDO712 and NCDO2031. In the nonlysogenic strains MG1363, NCDO763, LM0230, and LM2301, macrorestriction patterns revealed only one 220- and two 180-kb SmaI fragments. A 40-kb shift in the size of SmaI fragments would be in good agreement with the presence of a lactococcal temperate bacteriophage, and because no such 40-kb shift was observed in ApaI fingerprints, the regions that included the Sm5A or Sm5B fragments were analyzed in more detail. Southern hybridization was performed using the Ap3 fragment (160 kb) of MG1363 as a probe. This ApaI fragment is located in the Sm5A fragment on the physical map of the MG1363 chromosome (Fig. 3). The Ap3 probe hybridized with one 180-kb SmaI fragment in strains NCDO763, MG1363, LM0230, and LM2301 and with one 220-kb SmaI fragment in strains NCDO712 and NCDO2031-C2 (Table 2). For the ApaI fingerprints, the Ap3 probe hybridized with the 160-kb ApaI fragment in strains NCDO763, MG1363, LM0230, and LM2301 and also with a unique 165-kb ApaI fragment in strains NCDO712 and NCDO2031 (Table 2). From these results, we concluded that an uncharacterized excisable element of 40 kb, which contains one ApaI site on its genome, was accountable for the macrorestriction polymorphism observed in this region.

(iii) Genome rearrangement involving the conjugative sex factor.

Lactose plasmid conjugation in strains NCDO712 and NCDO763 frequently involves plasmid cointegration with a 50-kb cryptic conjugative element (sex factor), an event that causes a cell aggregation phenotype and provides high-frequency transfer ability (75). The sex factor is located on a low-copy-number plasmid, pRS01, in strain ML3 (47). In contrast, it has been demonstrated that the sex factor was integrated into the chromosomes of strains NCDO712, NCDO505, and NCDO763 but not of strain NCDO2031 and was located on the largest SmaI fragment in strain MG1363 (18). In addition, these authors observed that the sex factor could be present as an occasionally labile extrachromosomal band in strain MG1363. Identification of the genome polymorphism that involved the sex factor was attempted by hybridization experiments using different probes. We have previously shown that the size variation of the Sm1 fragment (610 kb) is associated with the same size variation of the No2 fragment (230 kb) in strains NCDO763, NCDO2031, and LM2301 (37). Thus, fragment No2 of the MG12363 chromosome was used as probe for Southern hybridization with the genome of the nine strains. To demonstrate that this chromosomal rearrangement was strictly linked to the presence of the sex factor, we performed a similar experiment using the 5′ end of the cluA gene as a probe. This gene, cloned from the sex factor of strain MG1363 (20), contains an ApaI site and has been precisely located on the MG1363 genome map (Fig. 3).

Hybridization results, summarized in Table 2, clearly showed that the genomes of strains NCDO2031, LM0230, and LM2301 had a deletion of 50 kb for SmaI and NotI hybridization and that this event was strictly linked to the chromosomal excision of the entire sex factor. The ApaI rearrangement observed for these strains could be explained by the excision of the sex factor and therefore the removal of the ApaI site of the cluA gene, corresponding to the Ap4-Ap26 fragment junction. The genome of strain NCDO763 had a deletion of 30 kb in or close to the sex factor. In addition, the cluA probe revealed the presence of a 50-kb extrachromosomal labile form of the sex factor for strains MG1363 and NCDO712 and a 25-kb labile form for strain NCDO763.

(iv) Genome rearrangement associated with the location of the oligopeptide transport operon (Opp).

The Opp system plays a crucial role in the utilization of oligopeptides as a nitrogen source during the growth of L. lactis in milk (28, 31). The genes encoding the Opp system are organized in an operon-like structure (oppDFBCA), together with a gene (pepO) encoding an endopeptidase (74). It was found that the oppDFCBA-pepO operon is located on the chromosome in strains NCDO712, NCDO763, MG1363, and LM0230 and either on the chromosome or on the Lac-Prt plasmid in strain C2 (78). In addition, it was shown that strain LM2301 was devoid of the opp operon. This operon has been located on Sm6 (105-kb) and Ap10C (75-kb) fragments on MG1363 chromosome (Fig. 3). To study which restriction polymorphism is associated with the various locations of this operon, hybridization experiments were undertaken using different probes. Four regions of the opp-pepO operon (oppFB, oppCA, pepO and 5′ end of oppD) were used as probes for Southern hybridization with the ApaI and SmaI fingerprints of the nine strains.

Southern hybridizations using oppFB, oppCA, or pepO as probes (Table 2) revealed that all strains except LM2301 contained a chromosomal copy of the opp-pepO operon at the same location as strain MG1363 and confirmed that strain LM2301 lacked the entire operon on its chromosome. ISS1 hybridization helped us to determine the size of the opp deletion (Table 2). Thus, the shift in size of the Sm6 fragment (from 130 to 105 kb) indicated that the removal of the opp-pepO operon was correlated to a deletion of 25 kb. Moreover, this deletion removed the ApaI site located at the junction of the two adjacent Ap10C (75 kb) and Ap11 (69 kb) fragments, generating a new ApaI fragment of 120 kb (Table 2). Hybridization using the 5′ part of the oppD gene as a probe revealed an additional ApaI fragment of 69 kb for strains NCDO712, NCDO2031, and MG1363, 67 kb for strain LM0230, and 19 kb for strain NCDO763. The weaker hybridization signal of the ApaI fragment adjacent to the Ap10C fragment probably indicated a small duplication of part of this gene near the entire opp operon.

Furthermore, strains NCDO712, NCDO505, and NCDO2031 contained an additional 55-kb ApaI-SmaI fragment that strongly hybridized with all of the opp-pepO probes, indicating the presence of a second copy of the entire opp operon. Since we have shown that these two fragments correspond to the Lac-Prt plasmid, we concluded that the additional opp-pepO operon is located on this plasmid, as also observed for strain C2. Another unexpected result was observed for the plasmid-free strain LM0230, where one additional 65-kb ApaI fragment and one additional 58-kb SmaI fragment hybridized with all of the opp-pepO probes, suggesting that strain LM0230 contained two chromosomal copies of the entire opp operon. However, we failed to map the location of this second opp operon.

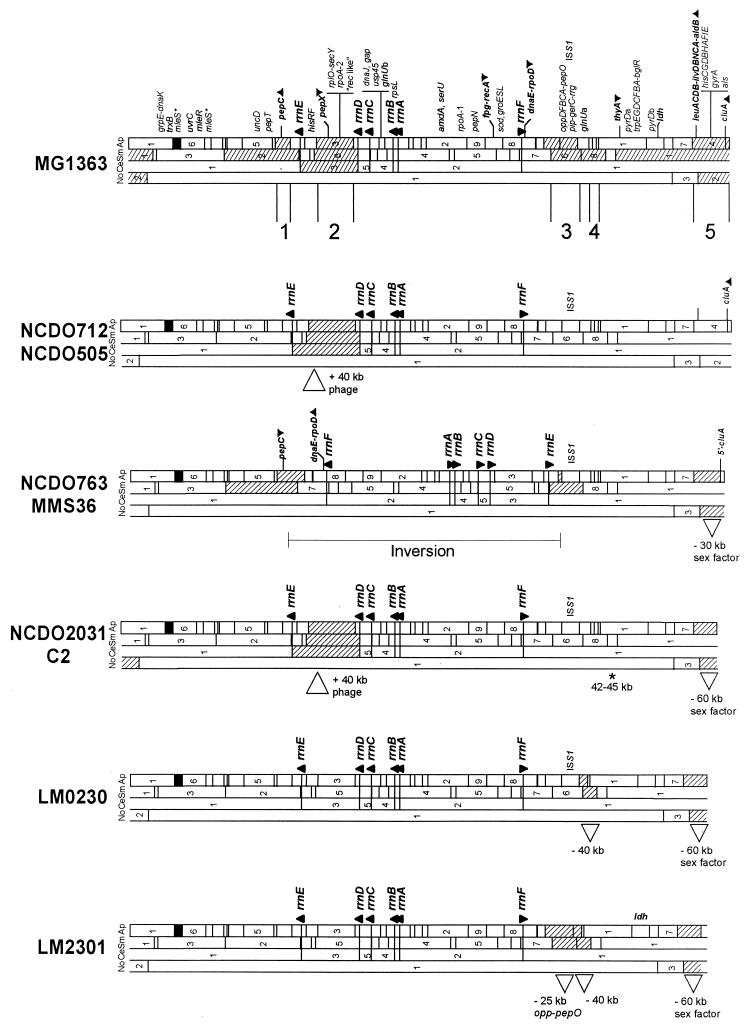

Deduction of the physical map of the NCDO712-NCDO505, NCDO763-MMS36, NCDO2031-C2, LM0230, and LM2301 chromosomes.

Characterization of genome rearrangements in the nine strains studied allowed the construction of a physical map of each corresponding chromosome. The five genome maps (Fig. 4) were deduced from the map of the MG1363 chromosome with the following assumptions: (i) common restriction fragments between two strains indicate conserved restriction sites on their genome maps, although fortuitous comigration cannot be ruled out; and (ii) the overall similarity of the patterns suggests that the restriction polymorphisms reflect a small number of changes to the map derived from MG1363, as opposed to an entirely different map for each strain.

FIG. 4.

Chromosome map of the different lactococcal strains deduced from the physical map of the reference strain MG1363. Abbreviations; Sm, SmaI; Ap, ApaI; No, NotI; Ce, I-CeuI.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the macrorestriction genome analysis of clonal variants of L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains. These strains can be considered adequate candidates for studying genome plasticity in gram-positive bacteria because their biological relationship is known (13). All strains are derivatives of strain NCDO712, an industrial strain that was isolated and recorded at the National Collection of Dairy Organisms in the United Kingdom in the early 1950s. The strain NCDO712 was subcultured under laboratory conditions for two decades before being rerecorded under different names (NCDO505, NCDO763, and NCDO2031) and/or genetically modified in the early 1980s (MG1363, MMS36, LM0230, and LM2301) (Fig. 1).

Comparative analysis of macrorestriction patterns generated with ApaI and SmaI endonucleases revealed a high degree of genomic similarity among the nine strains studied, with a similarity coefficient (SD) greater than 0.8. This result implies that comigrating restriction fragments correspond to conserved chromosomal regions at the genetic level (i.e., conservation of the gene order) as well as at a physical level (i.e., conservation of the location of restriction sites). However, at least two examples of fortuitous comigration of unrelated restriction fragments were observed. In the first case, a 105-kb SmaI fragment was present in all but LM0230 fingerprints. Southern hybridization analysis (ISS1 and Sm8 probes on SmaI fragments [Table 2]) clearly demonstrated that the 105-kb SmaI fragment in strain LM2301 was unrelated to the 105-kb SmaI fragment of other strains but corresponded to the 130-kb SmaI fragment in strains NCDO712, NCDO2031, LM0230, and MG1363 and to the 160-kb fragment in strain NCDO763. The second example involved the 120-kb ApaI fragment found in the NCDO763 and LM2301 fingerprints. In strain LM2301, this fragment corresponds to the fusion of two fragments (Ap10C and Ap11) due to the deletion of a 25-kb region carrying the opp-pepO operon. Strain NCDO763 contains two 120-kb ApaI fragments, one that was created by the 30-kb deletion in or near the sex factor region and one that was the result of a large chromosomal inversion that combined the Ap11 and Ap12B fragments (11). Nevertheless, we are confident that fortuitous comigration of independent restriction fragments is rare and that the only consequence may be a slight overestimation of the genomic relatedness between the strains.

The chromosome map of the MG1363 strain was used to construct a genome map of each strain and to present a model that accounts for the observed differences in macrorestriction patterns. From the five polymorphic regions identified, it was possible to correlate a genetic event with each of the RFLPs observed (Fig. 1). Region 1 corresponds to one end of the large inversion of half of the chromosome in strain NCDO763 and its derivative (MMS36). Region 2 corresponds to the presence of a 40-kb unknown element in strains NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO2031, and C2. Region 3 corresponds to a deletion of 25 kb including the opp-pepO operon in strain LM2301 and to the second end of the chromosomal inversion in strains NCDO763 and MMS36. Region 4 corresponds to the integration of the φT712 prophage DNA in strains NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO763, MMS36, NCDO2031, C2, and MG1363. Region 5 corresponds to the 60-kb deletion of the whole conjugative sex factor region in strains NCDO2031, C2, LM0230, and LM2301 and to a corresponding 30-kb deletion in strains NCDO763 and MMS36.

The nine strains studied differ in their lysogenic status, which is determined by their ability to be lysed after exposure to UV irradiation (13, 46), their lysotypic phenotype, and their genomic content of prophage DNA. Strains NCDO712, NCDO505, NCDO2031, and C2 are all sensitive to UV irradiation, and their chromosome contains one prophage DNA (φT712 or equivalent) located in region 4 and the unknown 40-kb element located in region 2. Strains MG1363, NCDO763, and MMS36 are resistant to UV irradiation as well as to φT712 infection and contain only the prophage DNA located in region 4 of their genome. Strains LM0230 and LM2301 are resistant to UV irradiation but sensitive to spot lysis with φT712 phage and contain neither the prophage DNA in region 4 nor the 40-kb element in region 2. One hypothesis that could correlate the phenotypic and genomic data would be that the φT712 temperate phage is unable to produce infectious particles without the help of the uncharacterized 40-kb element. This unknown element could correspond to a defective prophage that is able to precisely excise itself from the chromosome like the defective phage Rac of E. coli (29) and is able to code for some functions that are necessary for the structural integrity of the φT712 virions as does the P2 phage for the P4 phage of E. coli (38). Only strains carrying the DNA from the φT712 prophages and the 40-kb element would give φT712 phage particles after UV induction. Strains containing only φT712 prophage would not be UV inducible but would remain resistant to infection by φT712 particles. Only strains devoid of both elements would correspond to authentic phage-cured strains that are not UV inducible and would be sensitive to lysis by φT712 particles.

Another source of genomic rearrangement between the strains studied corresponded to the presence of the chromosomal conjugative sex factor. The strains can be clustered into three groups. The first group, made up of strains NCDO712, NCDO505, and MG1363, contains a complete conjugative factor of 50 kb that is integrated at the target site of the chromosome. This element is able to self-excise from the chromosome with an efficiency high enough to be visualized in PFGE. Strains of the second group, NCDO2031, C2, LM0230, and LM2301, have lost the whole conjugative element from their chromosome and are therefore unable to promote high-efficiency conjugation. Strains of the third group, NCDO763 and MMS36, have lost approximately 30 kb in or near the sex factor. It was found that, in addition to the attP site of 24 bp, two additional 13-bp direct repeats (flip1 and flip2) are present in the sex factor and are located 30 kb apart (21). As such, it is tempting to postulate that this deletion arose by accidental recombination between the two flip sites.

Analysis of the macrorestriction polymorphism associated with the location of opp-pepO gave intriguing findings. All strains except LM2301 contained a chromosomal copy of the opp-pepO operon. Strains NCDO712, NCDO505, and NCDO2031 contained an additional copy of this operon located on the Lac-Prt plasmid, whereas strain LM0230 seemed to contain a second chromosomal copy of the operon. The differences in copy number and/or chromosomal location, as well as the size of the deletion in the LM2301 strain, which is three times bigger than the size of the operon, suggest that opp-pepO belongs to a larger genetic element with a structure similar to a transposon, as already described for the lactococcal nis-sac operon (57). A similar duplication of a chromosomal gene was previously observed in L. lactis strain NCDO763, where the pepF gene was found to be duplicated and the second copy was located in the Lac-Prt plasmid (48).

In conclusion, we found that a physical chromosome map, combined with comparative analysis of PFGE macrorestriction patterns and Southern hybridization experiments, can be used to characterize the genetic events that are responsible for genome rearrangements between genetically related strains. In addition, they can be used to construct genome maps by comparison of restriction patterns without the need for direct experimental investigations for each chromosome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathalie Campo, Hafed Nedjari, and Guillaume Serin for skillful assistance with experimental work and A. Edelman for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (UPR9007), from the Région Midi-Pyrénées (RECH 9609795), and from UE-BIOTECH Programme (CT 96-0498).

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to Orian Le Bourgeois.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D G, McKay L L. Isolation of a recombination-deficient mutant of Streptococcus lactis ML3. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:930–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.930-932.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkenbihl R P, Vielmetter W. Cosmid-derived map of E. coli strain BHB2600 in comparison to the map of strain W3110. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5057–5069. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotin A, Mauger S, Malarme K, Ehrlich S D, Sorokin A. Low-redundancy sequencing of the entire Lactococcus lactis IL1403 genome. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:27–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borecka P, Rosypal S, Pantucek R, Doskar J. Localization of prophages of serological group B and F on restriction fragments defined in the restriction map of Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 8325. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canard B, Cole S T. Lysogenic phages of Clostridium perfringens: mapping of the chromosomal attachment sites. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;66:323–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canard B, Saint-Joanis B, Cole S T. Genomic diversity and organization of virulence genes in the pathogenic anaerobe Clostridium perfringens. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson C R, Gronstad A, Kolsto A B. Physical maps of the genomes of three Bacillus cereus strains. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3750–3756. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3750-3756.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson C R, Johansen T, Lecadet M-M, Kolsto A B. Genomic organization of the entomopathogenic bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. berliner 1715. Microbiology. 1996;142:1625–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casjens S, Delange M, Ley III H L, Rosa P, Huang W M. Linear chromosome of Lyme disease agent spirochetes: genetic diversity and conservation of gene order. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2769–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2769-2780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole S T, Saint Girons I. Bacterial genomics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:139–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daveran-Mingot M-L, Campo N, Ritzenthaler P, Le Bourgeois P. A natural large chromosomal inversion in Lactococcus lactis is mediated by homologous recombination between two insertion sequences. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4834–4842. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4834-4842.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson B E, Kordias N, Dobos M, Hillier A J. Genomic organization of lactic acid bacteria. In: Venema G, Huis in't Veld J H J, Hugenholtz J, editors. Lactic acid bacteria: genetics, metabolism and applications. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies F L, Underwood H M, Gasson M J. The value of plasmid profile for strain identification in lactic streptococci and the relationship between Streptococcus lactis 712, ML3 and C2. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981;51:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delorme C, Godon J J, Ehrlich S D, Renault P. Mosaic structure of large regions of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris chromosome. Microbiology. 1994;140:3053–3060. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempsey J A F, Wallace A B, Cannon J G. The physical map of the chromosome of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis shows complex rearrangements relative to the chromosome of the two mapped strains of the closely related species N. gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6390-6400.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonstein M, Haselkorn R. Physical mapping of bacterial genomes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3361–3369. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3361-3369.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasson M J, Swindell S R, Maeda S, Dodd H M. Molecular rearrangement of lactose plasmid DNA associated with high-frequency transfer and cell aggregation in Lactococcus lactis 712. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3213–3223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs C P, Meyer T F. Genome plasticity in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godon J J, Jury K, Shearman C A, Gasson M J. The Lactococcus lactis sex-factor aggregation gene cluA. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godon J J, Pillidge C J, Jury K, Gasson M J. Caractérisation d'un élément conjugatif original: le facteur sexuel de Lactococcus lactis 712. Lait. 1996;76:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grothues D, Tümmler B. New approaches in genome analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: application to the analysis of Pseudomonas species. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2763–2776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hackett N R, Bobovnikova Y, Heyrovska N. Conservation of chromosomal arrangement among three strains of the genetically unstable archaeon Halobacterium salinarium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7711–7718. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7711-7718.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hightower R C, Metge D W, Santi D V. Plasmid migration using orthogonal-field-alternation gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8387–8398. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himmelreich R, Plagens H, Hilbert H, Reiner B, Herrman R. Comparative analysis of the genomes of the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:701–712. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Israelsen H, Hansen E B. Insertion of transposon Tn917 derivatives into the Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis chromosome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:21–26. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.21-26.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansen T, Carlson C R, Kolsto A B. Variable numbers of rRNA gene operons in Bacillus cereus strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;136:325–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juillard V, Le Bars D, Kunji E R S, Konings W N, Gripon J C, Richard J. Oligopeptide are the main source of nitrogen for Lactococcus lactis during growth in milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3024–3030. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3024-3030.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser K, Murray N E. Physical characterisation of the “Rac prophage” in E. coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;175:159–174. doi: 10.1007/BF00425532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krawiec S, Riley M. Organization of the bacterial chromosome. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:502–539. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.502-539.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunji E R S, Hagting A, de Vries C J, Juillard V, Haandrikman A J, Poolman B, Konings W N. Transport of β-casein-derived peptides by the oligopeptide transport system is a crucial step in the proteolytic pathway of Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1569–1574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leblond P, Fischer G, Francou F X, Berger F, Guérineau M, Decaris B. The unstable region of Streptomyces ambofaciens includes 210 kb terminal inverted repeats flanking the extremities of the linear chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:261–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.366894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leblond P, Redenbach M, Cullum J. Physical map of the Streptomyces lividans 66 genome and comparison with that of the related strain Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3422–3429. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3422-3429.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Bourgeois P, Lautier M, Mata M, Ritzenthaler P. Physical and genetic map of the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6752–6762. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6752-6762.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Bourgeois P, Lautier M, van den Berghe L, Gasson M J, Ritzenthaler P. Physical and genetic map of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 chromosome: comparison with that of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 reveals a large genome inversion. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2840–2850. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2840-2850.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Bourgeois P, Mata M, Ritzenthaler P. Genome comparison of Lactococcus strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;59:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Bourgeois P, Mata M, Ritzenthaler P. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a tool for studying the phylogeny and genetic history of lactococcal strains. In: Dunny G M, Cleary P P, McKay L L, editors. Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci and enterococci. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1991. pp. 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindqvist B H, Deho G, Calendar R. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:683–702. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.683-702.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S L, Sanderson K E. I-CeuI reveals conservation of the genome of independent strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3355–3357. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3355-3357.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S L, Sanderson K E. The chromosome of Salmonella paratyphi A is inverted by recombination between rrnH and rrnG. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6585–6592. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6585-6592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S L, Sanderson K E. Highly plastic chromosomal organization in Salmonella typhi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10303–10308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopez-Garcia P, St Jean A, Amils R, Charlebois R L. Genomic stability in the archaeae Haloferax volcanii and Haloferax mediterranei. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1405–1408. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1405-1408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lucey M, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F. Relationship between Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 952, an industrial lactococcal starter culture and strains 712, ML3 and C2. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall P, Lemieux C. Cleavage pattern of the homing endonuclease encoded by the fifth intron in the chloroplast subunit rRNA-encoding gene of Chlamydomonas eugametos. Gene. 1991;104:1241–1245. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90256-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKay L L, Baldwin K A. Induction of prophage in Streptococcus lactis by ultraviolet irradiation. Appl Microbiol. 1973;25:682–684. doi: 10.1128/am.25.4.682-684.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKay L L, Baldwin K A, Efstathiou J D. Transductional evidence for plasmid linkage of lactose metabolism in Streptococcus lactis C2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1976;32:45–52. doi: 10.1128/aem.32.1.45-52.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mills D A, Choi C K, Dunny G M, McKay L L. Genetic analysis of regions of the Lactococcus lactis plasmid pRS01 involved in conjugative transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4413–4420. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4413-4420.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nardi M, Renault P, Monnet V. Duplication of the pepF gene and shuffling of DNA fragments on the lactose plasmid of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4164–4171. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4164-4171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nikolskaya T, Fonstein M, Haselkorn R. Alignment of a 1.2 Mb chromosomal region from three strains of Rhodobacter capsulatus reveals a significantly mosaic structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10609–10613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ojaimi C, Davidson B E, Saint Girons I, Old I G. Conservation of gene arrangement and an unusual organization of rRNA genes in the linear chromosomes of the lyme disease spirochaetes Borrelia burgdorferi, B. garinii, and B. afzelii. Microbiology. 1994;140:2931–2940. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okstad O A, Hegna I, Lindback T, Rishovd A L, Kolsto A B. Genome organization is not conserved between Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1999;145:621–631. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-3-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins J D, Don Heath J, Sharma B R, Weinstock G M. XbaI and BlnI genomic cleavage maps of Escherichia coli K-12 strain MG1655 and comparative analysis of other strains. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:419–445. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philipp W J, Nair S, Guglielmi G, Lagranderie M, Gicquel B, Cole S T. Physical mapping of Mycobacterium bovis BCG Pasteur reveals differences from the genome map of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and from M. bovis. Microbiology. 1996;142:3135–3145. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Philipp W J, Poulet S, Eiglmeier K, Pascopella L, Balasubramanian V, Heym B, Bergh S, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R, Cole S T. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3132–3137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polzin K M, Shimizu-Kadota M. Identification of a new insertion element, similar to gram-negative IS26, on the lactose plasmid of Streptococcus lactis ML3. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5481–5488. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5481-5488.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powell I B, Achen M G, Hillier A J, Davidson B E. A simple and rapid method for genetic transformation of lactic streptococci by electroporation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:655–660. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.655-660.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rauch P J G, de Vos W M. Characterization of the novel nisin-sucrose conjugative transposon Tn5276 and its insertion in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1280–1287. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1280-1287.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Redenbach M, Flett F, Piendl W, Glocker I, Rauland U, Wafzig O, Kliem R, Leblond P, Cullum J. The Streptomyces lividans 66 chromosome contains a 1 MB deletogenic region flanked by two amplifiable regions. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:255–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00284676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Römling U, Greipel J, Tümmler B. Gradient of genomic diversity in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Römling U, Schmidt K D, Tümmler B. Large genome rearrangements discovered by the detailed analysis of 21 Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone C isolates found in environment and disease habitats. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:386–404. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roussel Y, Bourgoin F, Guedon G, Pebay M, Decaris B. Analysis of the genetic polymorphism between three Streptococcus thermophilus strains by comparing their physical and genetic organization. Microbiology. 1997;143:1335–1343. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roussel Y, Pebay M, Guedon G, Simonet J M, Decaris B. Physical and genetic map of Streptococcus thermophilus A054. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7413–7422. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7413-7422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simske J S, Scherer S. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of circular DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4359–4365. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.11.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smeltzer M S, Hart M E, Iandolo J J. The effect of lysogeny on the genomic organization of Staphylococcus aureus. Gene. 1994;138:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy: the principles and practice of numerical classification. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman & Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tabata K, Hoshino T. Mapping of 61 genes on the refined physical map of the chromosome of Thermus thermophilus HB27 and comparison of genome organization with that of T. thermophilus HB8. Microbiology. 1996;142:401–410. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanskanen E I, Tulloch D L, Hillier A J, Davidson B E. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI digest of lactococcal genomic DNA, a novel method of strain identification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3105–3111. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.10.3105-3111.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tigges E, Minion F C. Physical map of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4157–4159. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4157-4159.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Toda T, Itaya M. I-CeuI recognition sites in the rrn operons of the Bacillus subtilis 168 chromosome: inherent landmark for genome analysis. Microbiology. 1995;141:1937–1945. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-8-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trautwetter A, Ritzenthaler P, Alatossava T, Mata-Gilsinger M. Physical and genetic characterization of the genome of Lactobacillus lactis bacteriophage LL-H. J Virol. 1986;59:551–555. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.551-555.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tulloch D L, Finch L R, Hillier A J, Davidson B E. Physical map of the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis DL11 and localization of six putative rRNA operons. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2768–2775. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2768-2775.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tynkkynen S, Buist G, Kunji E R S, Kok J, Poolman B, Venema G, Haandrikman A J. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the oligopeptide transport system of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7523–7532. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7523-7532.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh P M, McKay L L. Recombinant plasmid associated with cell aggregation and high-frequency conjugation in Streptococcus lactis ML3. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:937–944. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.937-944.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ward A C, Hillier A J, Davidson B E, Powell I B. Stability analysis of the Lactococcus lactis DCR1 lactose plasmid using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Plasmid. 1993;29:70–73. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waterbury P G, Lane M J. Generation of lambda concatemers for use as pulsed-field electrophoresis size markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3930. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.9.3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu W, Gillies K, Kondo J K, Broadbent J R, McKay L L. Loss of plasmid-mediated oligopeptide transport system in lactococci: another reason for slow milk coagulation. Plasmid. 1996;35:145–155. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zuerner R L, Herrmann J L, Saint Girons I. Comparison of genetic maps for two Leptospira interrogans serovars provides evidence for two chromosomes and intraspecies heterogeneity. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5445–5451. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5445-5451.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]