Abstract

Background

Resections of the pancreatic body and tail reaching to the left of the superior mesenteric vein are defined as distal pancreatectomy. Most distal pancreatectomies are elective treatments for chronic pancreatitis, benign or malignant diseases, and they have high morbidity rates of up to 40%. Pancreatic fistula formation is the main source of postoperative morbidity, associated with numerous further complications. Researchers have proposed several surgical resection and closure techniques of the pancreatic remnant in an attempt to reduce these complications. The two most common techniques are scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant and stapler resection and closure.

Objectives

To compare the rates of pancreatic fistula in people undergoing distal pancreatectomy using scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant versus stapler resection and closure.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, Biosis and Science Citation Index from database inception to October 2015.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy (irrespective of language or publication status).

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and extracted the data. Taking into consideration the clinical heterogeneity between the trials (e.g. different endpoint definitions), we analysed data using a random‐effects model with Review Manager (RevMan), calculating risk ratio (RR) or mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

In two eligible trials, a total of 381 participants underwent distal pancreatic resection and were randomised to closure of the pancreatic remnant either with stapler (n = 191) or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure (n = 190). One was a single centre pilot RCT and the other was a multicentre blinded RCT. The single centre pilot RCT evaluated 69 participants in five intervention arms (stapler, hand‐sewn, fibrin glue, mesh and pancreaticojejunostomy), although we only assessed the stapler and hand‐sewn closure groups (14 and 15 participants, respectively). The multicentre RCT had two interventional arms: stapler (n = 177) and hand‐sewn closure (n = 175). The rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula was the main outcome, and it occurred in 79 of 190 participants in the hand‐sewn group compared to 65 of 191 participants in the stapler group. Neither the individual trials nor the meta‐analysis showed a significant difference between resection techniques (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.55 to 1.45; P = 0.66). In the same way, postoperative mortality and operation time did not differ significantly. The single centre RCT had an unclear risk of bias in the randomisation, allocation and both blinding domains. However, the much larger multicentre RCT had a low risk of bias in all domains. Due to the small number of events and the wide confidence intervals that cannot exclude clinically important benefit or harm with stapler versus hand‐sewn closure, there is a serious possibility of imprecision, making the overall quality of evidence moderate.

Authors' conclusions

The quality of evidence is moderate and mainly based on the high weight of the results of one multicentre RCT. Unfortunately, there are no other completed RCTs on this topic except for one relevant ongoing trial. Neither stapler nor scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy showed any benefit compared to the other method in terms of postoperative pancreatic fistula, overall postoperative mortality or operation time. Currently, the choice of closure is left up to the preference of the individual surgeon and the anatomical characteristics of the patient. Another (non‐European) multicentre trial (e.g. with an equality or non‐inferiority design) would help to corroborate the findings of this meta‐analysis. Future trials assessing novel methods of stump closure should compare them either with stapler or hand‐sewn closure as a control group to ensure comparability of results.

Keywords: Humans, Surgical Instruments, Surgical Staplers, Suture Techniques, Fibrin Tissue Adhesive, Operative Time, Pancreas, Pancreas/surgery, Pancreatectomy, Pancreatectomy/adverse effects, Pancreatectomy/methods, Pancreatectomy/mortality, Pancreatic Fistula, Pancreatic Fistula/epidemiology, Pancreatic Fistula/etiology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Surgical Mesh

Plain language summary

Which method of distal pancreatic surgery is safer and more effective: stapler or hand‐sewn closure?

Review question

To understand whether stapler or hand‐sewn closure is safer and more effective for distal pancreatectomy (removing the tail of the pancreas).

Background

The pancreas is an abdominal organ producing enzymes that aid in digestion and regulation of blood sugar. Cancer of the pancreas is one of the most lethal types of cancer, and the only chance of cure is through radical surgery that removes part of the organ (a surgical procedure known as a resection, and in this case, distal pancreatectomy). Unfortunately, pancreatic surgery is not easy to perform and is complicated by high rates of postoperative complications. One of the most difficult complications is pancreatic fistula, which is when pancreatic enzymes leak from the resection site into the abdominal cavity, reacting with other internal organs to cause pain, infection and bleeding. The best method to prevent such complications is still unknown. Cutting the pancreas with a scalpel and sewing it shut by hand is the oldest method. More recently, surgeons also have had the option of using stapling devices, which cut and close the tissue simultaneously. Today, these two methods are the most commonly used to remove the tail of the pancreas. The aim of this review is to compare which method is safer and more effective.

Study characteristics

We searched several electronic databases to find high quality trials about this topic. Two authors independently read reports on the trials to decide whether or not to include them in the review, and they independently extracted the trial data so as not to miss any important information. The search yielded two high quality trials including a total of 381 participants.

Key results

The statistical analyses resulted in similar rates of pancreatic fistula (about 35%), deaths after surgery (about 1%) and average operation time between the two operation methods.

Individual surgeons can choose which closure technique to use after removing of the tail of the pancreas according to their preferences and the participant's anatomic characteristics.

Quality of the evidence

More high quality trials on this topic would be beneficial, and studies investigating new methods should compare them either to stapler or hand‐sewn closure in order to ensure comparability of results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy for distal pancreatectomy.

| Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy | |||||

|

Patient or population: patients with distal pancreatectomy

Setting: Elective operations at primary and secondary care centres Intervention: stapler Comparison: hand‐sewn | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Hand‐sewn | Stapler | ||||

| Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula | 363 POPF per 1000 participants | 350 POPF per 1000 participants (102 less POPF to 81 more POPF per 1000 participants) |

RR 0.90 (0.55 to 1.45) |

381 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

| Mortality | 11 deaths per 1000 participants | 6 deaths per 1000 participants (6 less deaths to 26 more deaths per 1000 participants) |

RR 0.49 (0.05 to 5.40) |

381 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

| Operation Time | — | The mean operation time in the intervention groups was 15 min less (52 min shorter to 22 min longer) |

MD −14.98 min (− 52.82 to 22.87) |

381 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aAlthough Bassi 1999 was unblinded, this fact is unlikely to bias pooled results, and we consider this as having a low risk of bias. However, there was serious imprecision (due to the small number of events and the wide confidence intervals) that cannot exclude clinically important benefit or harm with stapler versus hand‐sewn closure.

Background

Description of the condition

Resections of the body and tail of the pancreas that reach to the left of the superior mesenteric vein are defined as distal pancreatectomy. Due to a lower incidence of pancreatic disease and delayed appearance of clinical symptoms in this part of the organ, distal pancreatectomies are performed less often than resections of the pancreatic head (Andren‐Sandberg 1999). Most distal pancreatectomies are performed electively (84%) for the following indications: chronic pancreatitis (24%), other benign diseases (22%), malignant diseases (18%), neuroendocrine tumours (14%) and cysts of the pancreas (6%). The remaining 16% are emergencies following abdominal trauma (Lillemoe 1999). In the past decade, advances in surgical technique have reduced the operative mortality rate of pancreatic resections to below 5% in high‐volume centres (Büchler 2003; Trede 1990; Yeo 1997), although morbidity rates have generally remained unchanged (ranging from 30% to 40%) (Bassi 2001; Gouma 2000; Richter 2003). Pancreatic fistula formation is a main source of postoperative morbidity and is associated with numerous further complications, such as intra‐abdominal abscesses, wound infection, sepsis, electrolyte imbalance, malabsorption and haemorrhage (Knaebel 2005). In general, postoperative complications following distal pancreatectomy prolong hospital stay and require additional specialised treatment, including re‐operation and interventional drainage (Adam 2002; Fernandez 1995; Lillemoe 1999).

Description of the intervention

The surgical technique used and the performing surgeon are considered to be the most relevant risk factors for fistula formation after distal pancreatectomy (Andren‐Sandberg 1999). With regard to the former, several surgical resection and closure techniques of the pancreatic remnant have been developed in an attempt to reduce complications, including ultrasonic dissection devices, different pancreatico‐enteric anastomosis, hand‐sewn suture techniques, stapled closure, application of meshes, jejunal seromuscular and gastric serosal patches, sealing using fibrin glue or fibrin patches and various combinations of the above (Bassi 1999). Since scalpel resection with hand‐sewn closure and stapler resection and closure account for the most commonly used methods and are broadly available, this review focused on these two methods. After scalpel transection of the pancreatic parenchyma, surgeons may sew the remnant closed by hand with surgical suture material. Alternatively, the stapler resection technique closes the pancreatic parenchyma with a stapling device and then transects it with a scalpel behind the staple line.

How the intervention might work

For hand‐sewn closure, surgeons usually use slowly resorbable sutures, whereas the staples in stapler closure are non‐resorbable. Furthermore, hand‐sewn closure seems to be more dependent on the skills of the individual surgeon and the stitch technique used, whereas stapler closure is a mechanical procedure, amenable to standardisation and reproduction by different surgeons. Stapler closure maybe less appropriate in soft pancreatic tissue because it has the potential to mash the tissue. Sometimes physicians use somatostatin to decrease the exocrine secretion of the pancreas and avoid postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) (Gurusamy 2013). In all resections for malignancies, surgeons also perform a splenectomy, which can be another source of morbidity. These factors might cause a difference between the two methods.

Why it is important to do this review

Since the management of the pancreatic remnant seems to be an unresolved and clinically relevant problem, a systematic review comparing the two most common techniques of distal pancreatectomy appears feasible and important. In preceding individual studies (Bassi 1999; Diener 2011), there was no evidence for superiority of either of these techniques. A meta‐analysis of all available randomised controlled trials might yield novel insights into potential differences because of an increased sample size and statistical power. Furthermore, regular updates in the future will help scientists and clinicians stay up to date about the current evidence on this topic. Therefore, this systematic review comparing scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant versus stapler resection and closure is highly relevant.

Objectives

To compare the rates of pancreatic fistula in people undergoing distal pancreatectomy using scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant versus stapler resection and closure.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

To begin with, we searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We would have included controlled clinical trials (CCTs) if we had not found any RCTs.

We included and analysed RCTs that assessed the effects of at least one of the two surgical procedures of interest (stapler or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure) and provided quantitative data on postoperative mortality, morbidity and survival, irrespective of the underlying pancreatic disease, publication status or language of the article. We did not include trials comparing laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy.

Types of participants

Adult patients undergoing elective distal pancreatectomy due to benign or malign pancreatic disease. We also analysed distal pancreatectomy in trauma patients with pancreatic duct lesions.

Types of interventions

We compared two surgical strategies.

Stapler resection and closure.

Scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

POPF, including rate of POPF and rate of clinically relevant POPF

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative mortality

-

Postoperative morbidity

Overall postoperative morbidity

Delayed gastric emptying

Postoperative haemorrhage

Intra‐abdominal fluid collection

Re‐operation rate

Re‐intervention rate

Perioperative parameters (blood replacement, operation time)

Quality of life

Survival

Search methods for identification of studies

See: the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group search strategy at http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clabout/articles/UPPERGI/frame.html

We conducted searches to identify all published and unpublished RCTs or CCTs referring to surgical techniques of distal pancreatectomy. The search strategy was capable of identifying studies in all languages, and when necessary we translated non‐English papers.

Electronic searches

We identified trials by searching:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2015, issue 10);

MEDLINE (1966 to October 2015);

EMBASE (1974 to October 2015);

Biosis (1989 to October 2015); and

Science Citation Index (1945 to October 2015).

Science Citation Index (1945 to October 2015).

We constructed the MEDLINE search strategy (Appendix 1) by using a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words relating to diseases of the pancreatic remnant and surgical techniques for distal pancreatectomy. We did not apply filters to limit the search to RCTs as we anticipated finding few in this field, and we left the review open to other study designs.

Searching other resources

We checked the references of retrieved relevant articles for additional trials and used the Science Citation Index to search for articles that cited the included studies. We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) for further trials. This register includes the ISRCTN and NIH ClinicalTrials.gov trials registers, among others. Moreover, we contacted investigators and experts in the field of pancreatic surgery to ensure identification of all relevant studies. We did not restrict the search to specific languages or years of publication.

Data collection and analysis

The analysis followed Cochrane recommendations (Higgins 2011a). Statistical guidance was available from the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group editorial base and the review authors' host institution. Due to the clinical heterogeneity, for example the use of different endpoint definitions, we chose a random‐effects model for the meta‐analyses.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (PP and FH) independently reviewed the title and abstract of every trial identified by the search to determine eligibility. Each contributor independently evaluated whether the trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria. If the abstract suggested that the study might be relevant, or if it the fulfilment of the inclusion criteria were unclear, we retrieved the full text for further assessment. We excluded papers not meeting the inclusion criteria and listed these articles with the reason for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We resolved any disagreements by discussion with a third review author (MKD), with no need for further consultation with the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group editors. Two authors (PP and FH) independently carried out data extraction for prespecified outcome parameters.

Data extraction and management

We reviewed included articles and extracted data from published and unpublished reports using a pre‐designed, standardised data form.

We extracted general study information, trial characteristics and study details.

General study information

Title, authors, contact address

Source

Published/unpublished

Year of publication

Trial sponsors

Trial characteristics

Method of randomisation

Blinding of outcome assessor, participant and caregiver

Criteria for participant inclusion and exclusion

Sample size and sample size calculation

Baseline characteristics and the similarities of groups at baseline

Withdrawals and losses to follow up

Setting

Study details

Participant characteristics including mean/median age, age range, sex ratio

The specific pancreatic diagnosis leading to the surgical intervention

Number of participants assigned to each treatment group

Detail of intervention regimens

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

According to empirical evidence (Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995), we assessed the methodological quality of the trials based on sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. We based quality components on Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Sequence generation

Low risk of bias: The method used is either adequate (e.g. computer generated random numbers, table of random numbers) or unlikely to introduce confounding.

Uncertain risk of bias: There is insufficient information to assess whether the method used is likely to introduce confounding.

High risk of bias: The method used (e.g. quasi‐randomised trials) is improper and likely to introduce confounding.

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias: The method used (e.g. central allocation) is unlikely to introduce bias in the final observed effect.

Uncertain risk of bias: There is insufficient information to assess whether the method used is likely to introduce bias in the estimate of effect.

High risk of bias: The method used (e.g. open random allocation schedule) is likely to introduce bias in the final observed effect.

Blinding of participants and outcome assessors

Blinding of surgeons to the surgical procedure is impossible. However, it is possible to blind the participants and the outcome assessors to the groups.

Low risk of bias: Blinding was performed adequately, or the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Uncertain risk of bias: There is insufficient information to assess whether the type of blinding used is likely to introduce bias in the estimate of effect.

High risk of bias: Blinding is absent or incomplete, and the outcome or the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias: The underlying reasons for the absence of outcome data are unlikely to make treatment effects depart from plausible values, or proper methods have been employed to handle missing data.

Uncertain risk of bias: There is insufficient information to assess whether the missing data mechanism, in combination with the method used to handle missing data, is likely to introduce bias in the estimate of effect.

High risk of bias: The crude estimate of effects (e.g. complete case estimate) will clearly be biased due to the underlying reasons for missing data, and the methods used to handle missing data are unsatisfactory.

Selective outcome reporting

Low risk of bias: The trial protocol is available, and trial authors have reported all of the prespecified outcomes that were of interest for the review.

Uncertain risk of bias: There is insufficient information to assess whether the magnitude and direction of the observed effect are related to selective outcome reporting.

High risk of bias: The authors have not reported all of the trial's prespecified primary outcomes.

Other bias

Baseline imbalance

Low risk of bias: There was no baseline imbalance in any important characteristics.

Uncertain risk of bias: The baseline characteristics were not reported.

High risk of bias: There was a baseline imbalance due to chance or due to imbalanced exclusion after randomisation.

Early stopping

Low risk of bias: Authors reported sample size calculation, and the trial either did not stop or it stopped according to a formal stopping rule at a point where the likelihood of observing an extreme intervention effect due to chance was low.

Uncertain risk of bias: Authors did not report sample size calculations, and it is not clear whether the trial stopped early or not.

High risk of bias: The trial stopped early due to an informal stopping rule, or it stopped early according to a formal stopping rule at a point where the likelihood of observing an extreme intervention effect due to chance was high.

Source of funding bias

Low risk of bias: The trial's source(s) of funding did not come from any parties that might have a conflicting interest (e.g. instrument manufacturer).

Uncertain risk of bias: The source of funding was not clear.

High risk of bias: The trial received funding from an instrument manufacturer.

We considered trials that were classified as having low risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data and selective outcome reporting to be trials at low risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

If possible, we summarised dichotomous data using risk ratio (RR) whilst presenting continuous data summaries as standardised mean differences (SMD) or mean differences (MD, as appropriate. We dichotomised data that were difficult to categorise or that were presented in different forms across trials and treated them as binary data. We provided the 95% confidence interval (CI) and the P value for all outcomes reported.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of included trials for missing data. We calculated missing standard deviations, if appropriate, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We investigated all results for clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity may be caused by differences in the study population, definition of outcome parameters or perioperative management. We explained clinical heterogeneity where appropriate and possible, and we investigated statistical heterogeneity by inspecting the forest plot and I2 statistic. We considered an I2 of less than 25% to indicate low heterogeneity and an I2 over 75% to indicate high heterogeneity. Had there been an extreme level of heterogeneity, we would have interpreted summary effect measures with caution.

Data synthesis

We secured the accuracy of data by means of double data entry. For each outcome, and when appropriate information was available from at least two trials, we combined data in a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform subgroup analysis. A subgroup analysis on texture of the pancreas (soft vs. hard tissue) would have been interesting, but it was not feasible due to lack of data.

We calculated pooled effect estimates using the random‐effects model because of the clinical heterogeneity of the trials (e.g. different endpoint definitions) (DerSimonian 1986). We investigated the results for statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic as mentioned above. Had there been an extreme level of heterogeneity, we would have interpreted the summary effect measures with caution.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses (i.e. systematic removal of each individual trial from the meta‐analysis) to investigate heterogeneity in case of more than two included trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

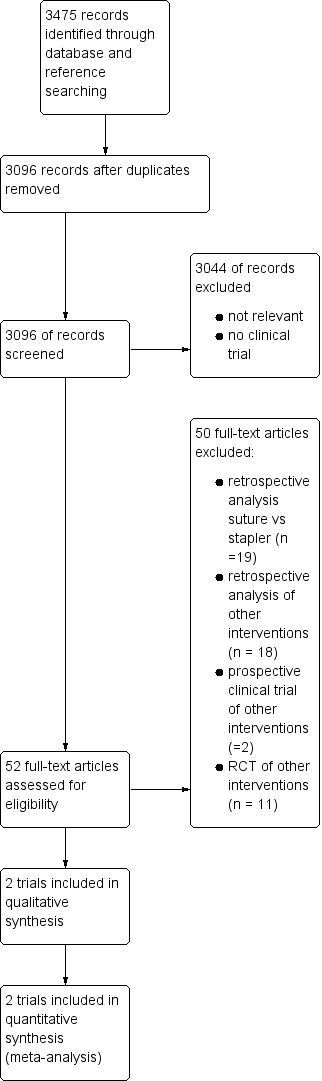

See: the study selection flowchart in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We identified a total of 3475 references through the electronic search. We excluded 379 duplicates and 3044 clearly irrelevant references after reading titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full text of 52 references for further assessment, as they were identified as clinical trials dealing with the topic of distal pancreatectomy. Of these, 39 were non‐randomised trials (one case‐control study and 38 clinical controlled trials), and 13 were RCTs. Only two were identified as RCTs investigating stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure as an intervention, and these were the trials we included in this review.

We also found one ongoing trial investigating the topic of this systematic review (JPRN‐UMIN000004838).

Included studies

A total of 381 participants underwent distal pancreatic resection and were randomised to closure of the pancreatic remnant either with stapler (n = 191) or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure (n = 190) in two trials (Bassi 1999, Diener 2011). Bassi 1999 was a single centre pilot trial from Italy that randomised a total of 69 participants into five intervention arms: stapler (TIA Multifire TA 60‐3.5 AutoSuture; n = 14), scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure (full‐thickness interrupted non‐absorbable sutures; n = 15), scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure plus fibrin glue (Tissucol; n = 11), scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure plus polypropylene mesh (Marlex; n = 15) and end‐to‐end pancreaticojejunostomy using a defunctioned (Roux) jejunal loop (n = 14). For this systematic review we only considered the two groups applicable to our review question.

Diener 2011 was a multicentre RCT based in Germany but taking place in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and England with two interventional arms: stapler (Ethicon TL 60 1.0 − 2.5 mm; n = 177) and scalpel transection with hand‐sewn closure (single‐stitched or running suture with slowly resorbable thread; n = 175).

The mean age of the participants in Diener 2011 was 60 years, and the proportion of females was 54%. Bassi 1999 did not report age but did report a proportion of 72% females for all five arms.

We show the outcomes reported in the trials in Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

The 47 excluded studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, and we describe the reasons for exclusion in Characteristics of excluded studies.

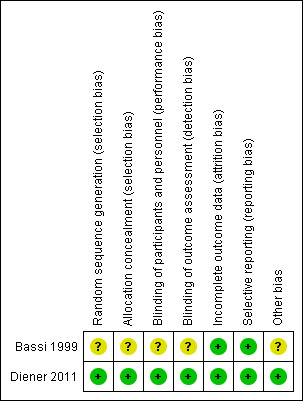

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Bassi 1999 did state the trial was randomised but gave no further description of sequence generation or allocation concealment (unclear risk). Diener 2011 used a computer‐generated sequence generation and a central web‐based allocation concealment (low risk).

Blinding

It is impossible to blind surgeons in most surgical clinical trials, for obvious reasons, so we did not grade this as meriting a judgement of high risk of bias. Bassi 1999 did not describe any kind of blinding, however, so we deemed it to carry an unclear risk. Diener 2011 blinded participants, outcome assessors and data analysts, so we considered this trial to have a low risk of bias for blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Both trials were at low risk of bias since there were no postrandomisation dropouts in Bassi 1999, and Diener 2011 clearly reported all withdrawals, dropouts and losses to follow‐up in a CONSORT flow diagram.

Selective reporting

No protocol was available for Bassi 1999, although all outcomes were clearly defined in the Methods section, so we considered this as having a low risk of bias. Diener 2011 reported all outcomes in accordance with the previously published trial protocol (Diener 2008).

We were not able to explore a potential publication bias because of too few included trials and therefore, we do not display any funnel plot.

Other potential sources of bias

Bassi 1999 did not provide sufficient baseline data on participant characteristics to compare them. In Diener 2011, an industry partner supplied the staplers, but authors stated that the company had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report, and all authors assumed final responsibility for the decision to publish.

Figure 2 displays the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

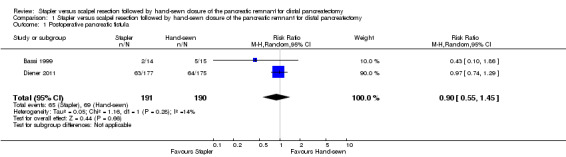

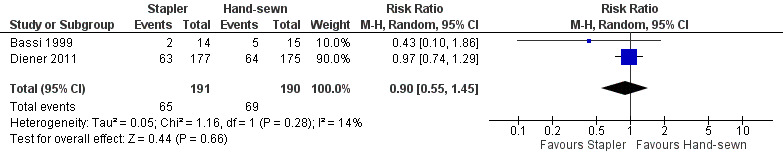

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF)

Both trials reported postoperative pancreatic (POPF) fistula rate. Bassi 1999 defined POPF as loss of at least 10 mL/d of drainage fluid with an amylase content of at least 1000 U/L beyond postoperative day 7. Five of 15 participants developed a POPF in the hand‐sewn group whereas 2 of 14 participants developed a fistula in the stapler group. The authors did not mention the time point of assessment. Diener 2011 used the 2005 definition of POPF established by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF): a drain output of any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase content greater than three times the serum amylase activity (Bassi 2005). Time point of assessment was after 7 days (primary endpoint) and 30 days (secondary endpoint) postoperatively. In that study, 64 of 175 participants in the hand‐sewn group and 63 of 177 participants in the stapler group developed POPF up to postoperative day 30 (Diener 2011). The difference was not significant in either trial. The pooled results slightly favoured stapler resection, but again, the results were not significant, and the 95% CI was relatively wide (RR 0.90; CI 0.55 to 1.45; P = 0.66; I2 = 14%; Analysis 1.1; Figure 3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, outcome: 1.1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula.

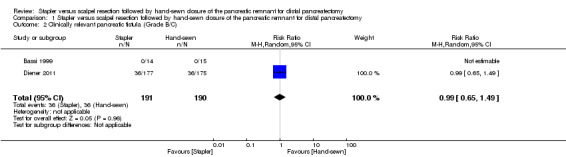

Only Diener 2011 reported the rates of clinically relevant POPF (grade B/C), since the ISGPF definition was published long after the trial by Bassi 1999. In Diener 2011, there were 36 clinically relevant POPFs (grade B/C) in both groups (RR 0.99; 95% CI of 0.65 to 1.49; P = 0.96; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 2 Clinically relevant pancreatic fistula (Grade B/C).

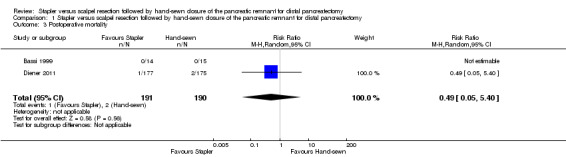

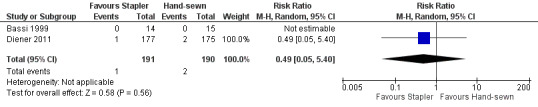

Overall postoperative mortality

Both trials reported postoperative mortality. In Bassi 1999, no participants died in either the stapler (n = 14) or the hand‐sewn (n = 15) groups. Diener 2011 reported one death in the stapler group (n = 177; 0.56%) and two deaths in the hand‐sewn group (n = 175; 1.14%). We could only analyse the results of Diener 2011, which favoured stapler resection but with a wide CI and no statistical significance (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.05 to 5.40; P = 0.56; Analysis 1.3; Figure 4).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 3 Postoperative mortality.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, outcome: 1.3 Postoperative mortality.

Postoperative morbidity

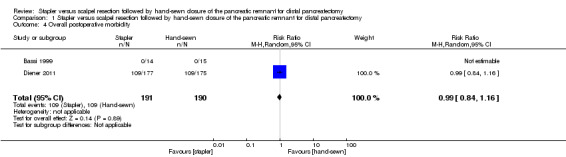

Overall postoperative morbidity

Only Diener 2011 provided data on overall postoperative morbidity. The trial showed similar rates with 109 complications in each group (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.16; P = 0.89; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 4 Overall postoperative morbidity.

Delayed gastric emptying

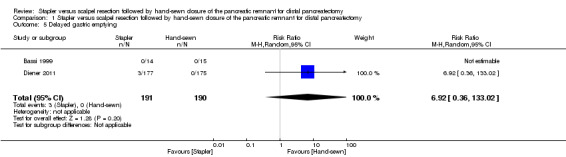

Only Diener 2011 reported data on delayed gastric emptying. This outcome did not occur in the hand‐sewn group, but three cases occurred in the stapler group, resulting in a non‐significant difference (RR 6.92; 95% CI 0.36 to 133.02; P = 0.20; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 5 Delayed gastric emptying.

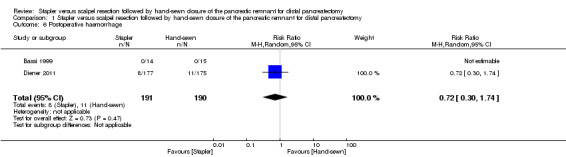

Postoperative haemorrhage

Bassi 1999 did not provide information on postoperative haemorrhage after distal pancreatectomy. In Diener 2011, 11 participants in the hand‐sewn group and 8 participants in the stapler group developed this outcome (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.74; P = 0.47 Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 6 Postoperative haemorrhage.

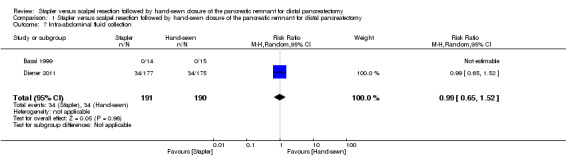

Intra‐abdominal fluid collection

Only Diener 2011 reported data on intra‐abdominal fluid collection, with 34 cases in each group of the trial (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.52; P = 0.96; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 7 Intra‐abdominal fluid collection.

Other outcomes of postoperative morbidity

None of the trials reported on re‐operation rate or re‐intervention rates, so we could not run any analyses of these endpoints.

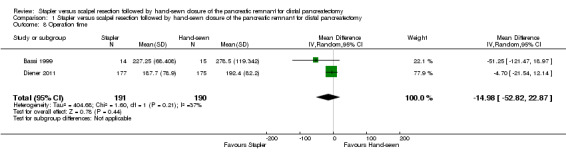

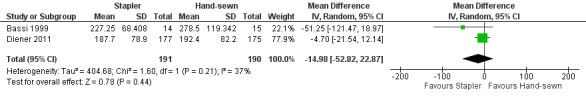

Perioperative parameters

Both trials reported operation time. In the combined result of Bassi 1999 and Diener 2011, stapler resection needed about 15 minutes less operation time but again this difference was not statistically significant (MD − 14.98 min; 95% CI − 52.82 to 22.87; P = 0.44; Analysis 1.8; Figure 5).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, Outcome 8 Operation time.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy, outcome: 1.8 Operation time.

Neither trial reported on other perioperative parameters (e.g. blood replacement).

Other outcomes

Neither trial reported on quality of life or survival.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not perform sensitivity analyses since there were only two trials (Bassi 1999; Diener 2011).

Discussion

Summary of main results

There are only two RCTs comparing stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy (Bassi 1999, Diener 2011). Of the reported results, we could run meta‐analyses for postoperative pancreatic fistula, mortality and operation time (Table 1). The risk ratio for all three outcomes favoured stapler resection, but results lacked statistical significance, and the confidence intervals were wide. Thus, there is still some uncertainty remaining concerning the effects of the different methods. None of the additional reported results from Diener 2011 demonstrated a difference between the two resection techniques. Currently, neither of the techniques has been shown to be superior to the other, and there is no need for surgeons to change their preferred surgical approach.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review is applicable for all surgeons performing and patients undergoing distal pancreatic resection with stapler or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant. Neither trial reported differences in participants' baseline characteristics, although Bassi 1999 did not show the data. Bassi 1999 did not report on distribution of splenectomies in the stapler or hand‐sewn group. The trial did not use somatostatin and only included participants with a soft pancreatic tissue. Diener 2011 reported the same number of splenectomies, use of somatostatin and soft pancreatic texture for both resection techniques. Bassi 1999 mentioned surgeons' experience as a key factor to success in pancreatic surgery but did not report on the experience of the surgeons who performed the intervention in their trial. In Diener 2011, 83% of surgeons performing the intervention had more than 10 years' experience and another 12% had 7 to 9 years experience, which is basically representative of the level of expertise among surgeons performing pancreatic surgery in that study setting.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of the evidence is moderate and mainly based on the high weight of the results of one multicentre RCT (Diener 2011) and another randomised pilot trial (Bassi 1999). Due to the small number of events and the wide confidence intervals, which do not exclude clinically important benefit or harm with stapler versus hand‐sewn closure, there is a serious risk of imprecision bias. Another currently ongoing trial (JPRN‐UMIN000004838) might add further valuable information on this topic.

Potential biases in the review process

Altough it is unlikely that our search missed any other RCTs comparing stapler versus hand‐sewn distal pancreatic resection, we could not assess publication bias. Our inclusion criteria for this review were very strict, as we did not aim to evaluate other existing techniques to manage the pancreatic remnant after distal resection. However, a meta‐analysis of these other techniques is not possible yet, as most of them have only been the subject of a single trial (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Either stapler or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant can be used for distal pancreatectomy. The current evidence suggests that both techniques are safe and have comparable postoperative complications, and there is no evidence to support a change in surgical approach if surgeons are used to one of these techniques. In some cases though, the anatomical situation might dictate the method used. With regard to the use of other novel techniques of remnant closure, there is a need for additional clinical trials to evaluate their safety and effectiveness.

Implications for research.

Additional multicentre trials, preferably with a non‐inferiority or equality design, would be beneficial for the body of evidence on this topic. For generalisability issues, trials from Asia or North America would complement the evidence of the two existing European trials, potentially corroborating the findings of the present meta‐analysis or exploring a possible difference among geographical regions. The trial protocol from Diener 2008 provides a good model for such a trial. A future trial stratifying the randomisation for pancreatic texture (soft versus hard) could add valuable information on the topic of stapler resection and closure versus scalpel resection with hand‐sewn closure. There might be a difference in effects between the two methods for soft versus hard pancreatic texture, and the trials included in this review do not address this question.

Since POPF rates are high, hovering around 35% regardless of the closure method used, there is still a need for further high quality research on innovative and novel closure methods. Future RCTs on management of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy should compare novel treatments to either stapler closure or scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure to ensure comparability of results. There is no rationale for comparing other novel strategies that have never been compared to reference methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group and Yuhong Yuan for editorial and literature search support.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt.

2. controlled clinical trial.pt.

3. randomized.ab.

4. placebo.ab.

5. clinical trials as topic.sh.

6. randomly.ab.

7. trial.ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

10. 8 not 9

11. exp Pancreas/

12. (pancrea$ adj3 tail).mp.

13. (acinar adj3 cell$).mp.

14. exp Pancreatic Ducts/

15. pancrea$.mp.

16. or/11‐15

17. (carcin$ or cancer$ or neoplas$ or tumour$ or tumor$ or cyst$ or growth$ or adenocarcin$ or malig$).mp.

18. 16 and 17

19. exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/

20. 18 or 19

21. (pancrea$ adj3 inflamm$).mp.

22. (pancrea$ adj3 traum$).mp.

23. (pancrea$ adj3 pseudocyst$).mp.

24. (pancrea$ adj3 alcohol$).mp.

25. (pancrea$ adj3 chronic$).mp.

26. (pancrea$ adj3 acute$).mp.

27. (pancrea$ adj3 fistula$).mp.

28. (pancrea$ adj3 complicat$).mp.

29. pancreatic fistula/

30. or/21‐29

31. exp Postoperative Complications/th, su, ep, pc, bl, me, im, et, pa, di, pp, mo, ge, dt, cl, ph, en, rh, co [Therapy, Surgery, Epidemiology, Prevention & Control, Blood, Metabolism, Immunology, Etiology, Pathology, Diagnosis, Physiopathology, Mortality, Genetics, Drug Therapy, Classification, Physiology, Enzymology, Rehabilitation, Complications]

32. postop$ complication$.ab,ti.

33. postop$ morbidit$.mp.

34. exp Pancreatectomy/

35. (pancrea$ adj3 distal$).mp.

36. (pancrea$ adj3 left$).mp.

37. (pancrea$ adj3 resect$).mp.

38. (pancrea$ adj3 operat$).mp.

39. (pancrea$ adj3 surg$).mp.

40. left$ resect$.mp.

41. (scalpel adj3 resection$).mp.

42. (hand‐sewn adj3 closure).mp.

43. (hand‐sewn adj3 suture$).mp.

44. exp Surgical Staplers/ or exp Surgical Stapling/

45. (staple$ adj3 resection$).mp.

46. (staple$ adj3 closure$).mp.

47. exp Suture Techniques/

48. or/31‐47

49. (20 or 30) and 48

50. 10 and 49

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1. exp Pancreas/

2. (pancrea$ adj3 tail).mp.

3. (acinar adj3 cell$).mp.

4. exp Pancreatic Ducts/

5. pancrea$.mp.

6. or/1‐5

7. (carcin$ or cancer$ or neoplas$ or tumour$ or tumor$ or cyst$ or growth$ or adenocarcin$ or malig$).mp.

8. 6 and 7

9. exp pancreas tumor/ or exp pancreas adenocarcinoma/ or exp pancreas carcinoma/ or exp pancreas islet cell carcinoma/ or exp pancreas islet cell tumor/ or exp pancreas cancer/

10. 8 or 9

11. (pancrea$ adj3 inflamm$).mp.

12. (pancrea$ adj3 traum$).mp.

13. (pancrea$ adj3 pseudocyst$).mp.

14. (pancrea$ adj3 alcohol$).mp.

15. (pancrea$ adj3 chronic$).mp.

16. (pancrea$ adj3 acute$).mp.

17. (pancrea$ adj3 fistula$).mp.

18. (pancrea$ adj3 complicat$).mp.

19. fistula.ab,ti.

20. or/11‐19

21. exp postoperative complication/dm, co, su, th, rh [Disease Management, Complication, Surgery, Therapy, Rehabilitation]

22. postop$ complication$.ab,ti.

23. postop$ morbidit$.mp.

24. exp Pancreatectomy/

25. exp pancreas surgery/

26. (pancrea$ adj3 distal$).mp.

27. (pancrea$ adj3 left$).mp.

28. (pancrea$ adj3 resect$).mp.

29. (pancrea$ adj3 operat$).mp.

30. (pancrea$ adj3 surg$).mp.

31. left$ resect$.mp.

32. (scalpel adj3 resection$).mp.

33. (hand‐sewn adj3 closure).mp.

34. (hand‐sewn adj3 suture$).mp.

35. exp Surgical Staplers/ or exp Surgical Stapling/

36. (staple$ adj3 resection$).mp.

37. (staple$ adj3 closure$).mp.

38. exp Suture Techniques/

39. or/21‐38

40. (10 or 20) and 39

41. random:.tw. or placebo:.mp. or double‐blind:.tw.

42. 40 and 41

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

1. Pancreas.ab,ti.

2. (pancrea$ adj3 tail).mp.

3. (acinar adj3 cell$).mp.

4. Pancreatic Ducts.ab,ti.

5. pancrea$.mp.

6. or/1‐5

7. (carcin$ or cancer$ or neoplas$ or tumour$ or tumor$ or cyst$ or growth$ or adenocarcin$ or malig$).mp.

8. 6 and 7

9. (pancreas tumor or pancreas adenocarcinoma or pancreas carcinoma or pancreas islet cell carcinoma or pancreas islet cell tumor or pancreas cancer).ab,ti. [mp=title, abstract, full text, caption text]

10. 8 or 9

11. (pancrea$ adj3 inflamm$).mp.

12. (pancrea$ adj3 traum$).mp.

13. (pancrea$ adj3 pseudocyst$).mp.

14. (pancrea$ adj3 alcohol$).mp.

15. (pancrea$ adj3 chronic$).mp.

16. (pancrea$ adj3 acute$).mp.

17. (pancrea$ adj3 fistula$).mp.

18. (pancrea$ adj3 complicat$).mp.

19. fistula.ab,ti.

20. or/11‐19

21. postoperative complication.ab,ti.

22. postop$ complication$.ab,ti.

23. postop$ morbidit$.mp.

24. Pancreatectomy.ab,ti.

25. pancreas surgery.ab,ti.

26. (pancrea$ adj3 distal$).mp.

27. (pancrea$ adj3 left$).mp.

28. (pancrea$ adj3 resect$).mp.

29. (pancrea$ adj3 operat$).mp.

30. (pancrea$ adj3 surg$).mp.

31. left$ resect$.mp.

32. (scalpel adj3 resection$).mp.

33. (hand‐sewn adj3 closure).mp.

34. (hand‐sewn adj3 suture$).mp.

35. (Surgical Staplers or Surgical Stapling).ab,ti.

36. (staple$ adj3 resection$).mp.

37. (staple$ adj3 closure$).mp.

38. Suture Techniques.ab,ti.

39. or/21‐38

40. (10 or 20) and 39

41. randomized controlled trial.ab,ti.

42. controlled clinical trial.ab,ti.

43. randomized.ab.

44. placebo.ab.

45. clinical trials.ab.

46. randomly.ab.

47. trial.ti.

48. or/41‐47

49. animals.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, caption text]

50. humans.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, caption text]

51. 49 not (49 and 50)

52. 48 not 51

53. 52 and 40

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Stapler versus scalpel resection followed by hand‐sewn closure of the pancreatic remnant for distal pancreatectomy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.55, 1.45] |

| 2 Clinically relevant pancreatic fistula (Grade B/C) | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.65, 1.49] |

| 3 Postoperative mortality | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.05, 5.40] |

| 4 Overall postoperative morbidity | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.84, 1.16] |

| 5 Delayed gastric emptying | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.92 [0.36, 133.02] |

| 6 Postoperative haemorrhage | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.30, 1.74] |

| 7 Intra‐abdominal fluid collection | 2 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.65, 1.52] |

| 8 Operation time | 2 | 381 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐14.98 [‐52.82, 22.87] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bassi 1999.

| Methods | Single centre pilot RCT with 5 study arms from Italy Trial duration: 1993 to 1997 Trial registered: no Protocol available: no Patients randomised: 69 Exclusion after randomisation (total): 0 Losses to follow‐up (total): 0 Description of sample size calculation: none (pilot trial) Intention‐to treat analysis: unknown (no losses to follow‐up) |

|

| Participants | Number: 69 (group 1 (suture): 15; group 2 (stapler): 14; group 3 (suture + fibrin): 11; group 4 (suture + mesh): 15; group 5 (pancreaticojejunostomy): 14) Age: not stated Sex (total): female = 19, male = 50 Sex (study arms): not stated Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing left pancreatic resection Exclusion criteria: not stated Use of somatostatin: none Splenectomies: 61 (groups unknown) Soft pancreas: 69 (groups unknown) Disease: cystic tumours 30, neuroendocrine tumours 15, ductal adenocarcinomas 13, intraductal mucinous tumours 10, other 1 (groups unknown) |

|

| Interventions | Group 1 (suture): simple ligation of the main duct with non‐absorbable sutures and closure of the stump with full‐thickness interrupted sutures Group 2 (stapler): mechanical suturing with a stapler (T.I.A. Multifire TA 60‐3.5 Auto Suture) Group 3 (suture + fibrin): 5 mL fibrin glue (Tissucol) applied to the stump after closure, as in group 1 Group 4 (suture + mesh): polypropylene mesh (Marlex) applied to the stump after closure, as in group 1 Group 5 (pancreaticojejunostomy): end‐to‐end pancreaticojejunostomy using a defunctioned (Roux) jejunal loop Only groups 1 and 2 included in review analyses |

|

| Outcomes | Rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (defined as loss of at least 10 mL/d of drainage fluid with an amylase content of at least 1000 U/L beyond postoperative day 7) Postoperative mortality Operation time Time point of assessment: unknown |

|

| Notes | Funding source: not stated | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly allocated" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly allocated" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Blinding not stated, but outcome unlikely to be biased by blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Most likely unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No protocol available; but outcome clearly defined in Methods section and exactly reported in Results section |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Potential funding bias, potential baseline imbalances |

Diener 2011.

| Methods | Multicentre (n = 21), multinational (Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and England) blinded RCT with 2 study arms Trial duration: 2006 to 2009 Trial registered: ISRCTN18452029 Protocol available: Diener 2008 Patients randomised: 450 Exclusion after randomisation (total): 98

Losses to follow‐up (total): 0 Description of sample size calculation: assumed pancreatic fistula rate of 35% in the hand‐sewn group and an absolute risk reduction of 15% in the stapler group. At least 151 patients per group were needed to detect this absolute risk reduction at a two‐sided alpha‐level of 5% with a power of 80%. Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes |

|

| Participants | Number: 352 (group 1 (suture): 175; group 2 (stapler): 177) Mean age (SD): group 1 (suture): 59.8 (13.6); group 2 (stapler): 59.8(14.1) Sex (total): female = 191 (suture group 99, stapler group 92), m = 161 (suture group 76, stapler group 85) Inclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria.

Use of somatostatin.

Splenectomies: group 1 (suture): 148 (85%); group 2 (stapler): 145 (82%) Soft pancreas: same number (stratification for soft pancreas) Disease.

|

|

| Interventions | Group 1 (suture): After complete mobilisation of the pancreatic tail, the resection was performed with a surgical scalpel. Subsequent closure of the pancreatic remnant was achieved with a separately stitched ligation of the pancreatic duct, followed by either a single‐stitched or running suture of the entire pancreatic remnant. The suture material of choice was slowly absorbable monofilament thread, such as PDSTM or MonoPlusTM. A non‐absorbable suture was not permitted for hand‐sewn closure of the transected pancreas. The recommended suture strength is USP 4/0 and USP 5/0. Group 2 (stapler): Pancreatic resection and transection of the pancreatic body was executed using a linear stapling device (Ethicon TL 60) armed with a 60 mm magazine. The depth of the individual staple (1.0–2.5 mm) was chosen as needed. |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Funding: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Staplers were provided by Johnson & Johnson Medical (Industry partner did not have any role in planning, conducting or analysing of the trial) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers (Randomizer), stratified for centre and risk level |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central preoperative randomisation |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessor blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Clearly listed in CONSORT diagram with reasons of exclusion |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Pre‐study published and registered protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | Industry involvement (staplers provided), role of industry partner was stated explicitly |

DGE: delayed gastric emptying;POPF: postoperative pancreatic fistula; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; USP: United States Pharmacopeia.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Adam 2001 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; pancreaticojejunostomy versus suture |

| Antila 2014 | RCT: suture versus Roux‐Y binding pancreaticojejunal anastomosis |

| Balzano 2005 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Bilimoria 2003 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus no closure |

| Blansfield 2012 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture/stapler versus radiofrequency dissection |

| Carter 2013 | RCT: stapler/suture versus stapler/suture + falciform ligament patch and fibrin glue |

| Ceppa 2012 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus saline linked radiofrequency |

| Cogbill 1991 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler in pancreatic trauma patients |

| D'Andrea 1994 | RCT: suture versus fibrin sealing |

| Eguchi 2011 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Fahy 2002 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Ferrone 2008 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler with or without reinforced staple lines versus falciform patch |

| Fitzgibbons 1982 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Frozanpor 2010 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Goh 2008 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus both versus anastomosis |

| Hamilton 2012 | RCT: stapler versus mesh‐reinforced stapler |

| Harris 2010 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; scalpel (over‐sewn, not over‐sewn or anastomosis) versus stapler (over‐sewn or not over‐sewn) versus electrocautery (over‐sewn or not over‐sewn) |

| Hassenpflug 2012 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture/stapler versus covering of the remnant with falciform patch |

| Johnston 2009 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus mesh‐reinforced stapler |

| Kajiyama 1996 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Kamath 2013 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler (over‐sewn or not over‐sewn) versus electrocautery versus radiofrequency |

| Kawai 2013 | Prospective clinical controlled study: suture versus stapler versus bipolar scissors |

| Kim 2013 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus stapler with suture |

| Kivilaakso 1984 | RCT: distal resection versus lavation in fulminant pancreatitis |

| Kleef 2007 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus anastomosis versus seromuscular patch |

| Kuroki 2009 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus gastric wall covering |

| Lillemoe 1999 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus stapler over‐sewn versus anastomosis |

| Lorenz 2007 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Montorsi 2012 | RCT: suture/stapler versus suture/stapler with fibrin sealant patch |

| Nathan 2009 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus both |

| Ohwada 1998 | Prospective clinical controlled study; suture with fibrin sealing versus suture with "fibrin glue sandwich" |

| Okada 2014 | Retrospective analysis; Suture versus Isolated Roux‐en‐Y anastomosis of the pancreatic stump in a duct‐to‐mucosa fashion |

| Okano 2008 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Oláh 2009 | RCT: stapler versus stapler + seromuscular patch of jejunum |

| Pannegeon 2006 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler versus both |

| Ridolfini 2007 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Sa Cunha 2015 | RCT: suture/stapler versus suture/stapler with fibrin |

| Satoi 2013 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; ultrasonic dissection and suture versus ultrasonic dissection with pancreaticogastrostomy |

| Sepesi 2012 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus various staplers versus stapler with reinforcement |

| Shankar 1990 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus anastomosis |

| Sheehan 2002 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

| Sledzianowski 2005 | Prospective clinical controlled study: suture versus stapler versus fibrin glue reinforcement |

| Suc 2003 | RCT: stump closure versus ductal occlusion with fibrin glue |

| Suzuki 1995 | RCT: sutures versus suture + fibrin glue |

| Suzuki 1999 | RCT: suture versus ultrasonic dissector |

| Takeuchi 2003 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database: suture versus stapler |

| Thomay 2013 | retrospective analysis of prospective database; sutures versus stapler (over‐sewn or not over‐sewn) versus electrocautery |

| Wallace 2013 | Prospective clinical study with retrospective historical control group; stapler versus mesh‐reinforced stapler |

| Yamamoto 2009 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture/stapler versus mesh‐reinforced stapler |

| Zhao 2008 | Retrospective analysis of prospective database; suture versus stapler |

RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

JPRN‐UMIN000004838.

| Trial name or title | Safety of stapler versus non‐stapler closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy: a multicenter randomised controlled trial |

| Methods | Randomised |

| Participants | Planned sample size: 140, completed |

| Interventions | Stapler versus hand‐sewn |

| Outcomes | POPF |

| Starting date | 2011 |

| Contact information | National Cancer Center Hospital of Japan |

| Notes | — |

POPF: postoperative pancreatic fistula

Differences between protocol and review

We listed 'overall pancreas‐associated morbidity' as a primary outcome in the review protocol. However, we could not extract data for this endpoint from the primary trials and thus could not report on it. Nevertheless, we could report the individual secondary endpoints (delayed gastric emptying, postoperative haemorrhage) as provided by the primary trials.

We used the 2011 version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions instead of 2008 as cited in the protocol.

Contributions of authors

Conceiving the review: AU, MWB, MKD Coordinating the review: MWB Designing the review: PK, AU, MKD Data collection for the review: PP*, FH*, MKD Designing search strategies: PP Undertaking searches: PP*, FH*, UK, MKD Screening search results: PP*, FH*, UK, MKD Organising retrieval of papers: PP, PK, MKD Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: PP*, FH*, MKD Appraising quality of papers: PP*, FH*, UK, PK, AU, MKD Extracting data from papers: PP*, FH*, MKD Writing to authors of papers for additional information: PP, MKD Providing additional data about papers: PP*, FH*, MKD Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: PP*, FH*, UK, MKD Data management for the review: PP*, FH*, PK, MKD Entering data into RevMan: MKD Analysis of data: PP*, FH*, MKD Interpretation of data: PP*, FH*, PK, AU, MKD Providing a methodological perspective: PP*, FH*, UK, PK, MKD Providing a clinical perspective: PP*, FH*, PK, AU, MKD Providing a policy perspective: PP*, FH*, AU, MKD Providing a consumer perspective: PP*, FH*, PK, MKD Providing general advice on the review: AU, MWB, MKD Writing the review: PP*, FH*, UK, MKD Securing funding for the review: PK, AU, MKD Performing previous work that was the foundation of the current study: MKD

* Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of General, Visceral and Transplant Surgery, University of Heidelberg, Germany.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

One of the authors of this review (MKD) is also the lead author of Diener 2011, which could have potentially led to some bias. However, an independent reviewer (Yuhong Yuan) extracted data for this trial, and MKD was not involved in assessing the quality of the trial in order to reduce possible bias in this regard.

PP: no other conflict of interest FJH: no other conflict of interest UK: no other conflict of interest PK: no other conflict of interest AU: no other conflict of interest MWB: no other conflict of interest MKD: no other conflict of interest

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Bassi 1999 {published data only}

- Bassi C, Butturini G, Falconi M, Salvia R, Sartori N, Caldiron E, et al. Prospective randomised pilot study of management of the pancreatic stump following distal resection. HPB 1999;1(4):203–7. [Google Scholar]

Diener 2011 {published data only}

- Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand‐sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. The Lancet 2011;377(9776):1514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Adam 2001 {published data only}

Antila 2014 {published data only}

- Antila A, Sand J, Raty S, Nordback I, Laukkarinen J. Is Roux‐Y binding pancreatico‐jejunal anastomosis feasible for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy?. Pancreatology 2014;14(3 Suppl 1):S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Balzano 2005 {published data only}

- Balzano G, Zerbi A, Cristallo M, Carlo V. The unsolved problem of fistula after left pancreatectomy: the benefit of cautious drain management. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2005;9(6):837‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bilimoria 2003 {published data only}

- Bilimoria MM, Cormier JN, Mun Y, Lee JE, Evans DB, Pisters PW. Pancreatic leak after left pancreatectomy is reduced following main pancreatic duct ligation. British Journal of Surgery 2003;90(2):190‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blansfield 2012 {published data only}

Carter 2013 {published data only}

- Carter TI, Fong ZV, Hyslop T, Lavu H, Tan WP, Hardacre J, et al. A dual‐institution randomized controlled trial of remnant closure after distal pancreatectomy: does the addition of a falciform patch and fibrin glue improve outcomes?. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2013;17(1):102‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ceppa 2012 {published data only}

- Ceppa EP, McCurdy RM, Kilbane M, Nakeeb A, Schmidt CM, Zyromski NJ, et al. Does pancreatic stump closure method influence fistula rate after distal pancreatectomy?. Gastroenterology 2012;142(5):S‐1080. [Google Scholar]

Cogbill 1991 {published data only}

- Cogbill TH, Moore EE, Morris JA, Hoyt DB, Jurkovich GJ, Mucha P, et al. Distal pancreatectomy for trauma ‐ a multicenter experience. Journal of Trauma 1991;31(12):1600‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

D'Andrea 1994 {published data only}

- D'Andrea AA, Costantino V, Sperti C, Pedrazzoli S. Human fibrin sealant in pancreatic surgery: is it useful in preventing fistulas? A prospective randomized study. Italian Journal of Gastroenterology 1994;26(6):283‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eguchi 2011 {published data only}

Fahy 2002 {published data only}

- Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. American Journal of Surgery 2002;183(3):237‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferrone 2008 {published data only}

- Ferrone CR, Warshaw AL, Rattner DW, Berger D, Zheng H, Rawal B, et al. Pancreatic fistula rates after 462 distal pancreatectomies: staplers do not decrease fistula rates. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2008;12(10):1691‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fitzgibbons 1982 {published data only}

- Fitzgibbons TJ, Yellin AE, Maruyama MM, Donovan AJ. Management of the transected pancreas following distal pancreatectomy. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 1982;154(2):225‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frozanpor 2010 {published data only}

- Frozanpor F, Albiin N, Linder S, Segersvard R, Lundell L, Arnelo U. Impact of pancreatic gland volume on fistula formation after pancreatic tail resection. JOP: Journal of the Pancreas. E.S. Burioni Ricerche Bibliografiche (Corso Firenze 41/2, Genova 16136, Italy), 2010; Vol. 11, issue 5:439‐43. [PubMed]

Goh 2008 {published data only}

- Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, Cheow PC, Ong HS, Chan WH, et al. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: a 21‐year experience at a single institution. Archives of Surgery 2008;143(10):956‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hamilton 2012 {published data only}

- Hamilton NA, Porembka MR, Johnston FM, Gao F, Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, et al. Mesh reinforcement of pancreatic transection decreases incidence of pancreatic occlusion failure for left pancreatectomy: a single‐blinded, randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (530 Walnut Street,P O Box 327, Philadelphia PA 19106‐3621, United States), 2012; Vol. 255, issue 6:1037‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Harris 2010 {published data only}

- Harris LJ, Abdollahi H, Newhook T, Sauter PK, Crawford AG, Chojnacki KA, et al. Optimal technical management of stump closure following distal pancreatectomy: a retrospective review of 215 cases. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2010;14(6):998‐1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hassenpflug 2012 {published data only}

Johnston 2009 {published data only}

- Johnston FM, Cavataio A, Strasberg SM, Hamilton NA, Simon PO Jr, Trinkaus K, et al. The effect of mesh reinforcement of a stapled transection line on the rate of pancreatic occlusion failure after distal pancreatectomy: review of a single institution's experience. HPB. Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Division of Hepatobiliary, Pancreatic and Gastrointestinal Surgery, St. Louis, MO, USA., 2009; Vol. 11, issue 1:25‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Kajiyama 1996 {published data only}

- Kajiyama Y, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Akiyama H. Quick and simple distal pancreatectomy using the GIA stapler: report of 35 cases. British Journal of Surgery 1996;83(12):1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kamath 2013 {published data only}

- Kamath AS, Que FG, Harmsen WS, Seidu SA, Singh D, Alonso CA. Pancreatic stump leak after distal pancreatectomy: predictors and outcomes. Gastroenterology 2013; Vol. 144, issue 5 Suppl 1:S1129‐30.

Kawai 2013 {published data only}

- Kawai M, Tani M, Okada K, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, et al. Stump closure of a thick pancreas using stapler closure increases pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. American Journal of Surgery 2013;206(3):352‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim 2013 {published data only}

- Kim JH, Li G, Baek NH, Hwang JC, Hong J, Yoo BM, et al. Surgical outcomes of distal pancreatectomy. Hepato‐Gastroenterology 2013;60(126):1263‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kivilaakso 1984 {published data only}

- Kivilaakso E, Lempinen M, Makelainen A. Pancreatic resection versus peritoneal lavation for acute fulminant pancreatitis. A randomized prospective study. Annals of Surgery 1984; Vol. 199, issue 4:426‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Kleef 2007 {published data only}

- Kleeff J, Diener M K, Z'graggen K, Hinz U, Wagner M, Bachmann J, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Annals of Surgery 2007;245(4):573‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kuroki 2009 {published data only}

- Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Tsuneoka N, Adachi T, Kanematsu T. Gastric wall‐covering method prevents pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Hepato‐Gastroenterology 2009;56(91‐92):877‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lillemoe 1999 {published data only}

- Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Annals of Surgery 1999;229(5):693‐700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lorenz 2007 {published data only}

- Lorenz U, Maier M, Steger U, Topfer C, Thiede A, Timm S. Analysis of closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatic resection. HPB 2007;9(4):302‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Montorsi 2012 {published data only}

Nathan 2009 {published data only}

- Nathan H, Cameron JL, Goodwin CR, Seth AK, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy. Annals of Surgery 2009;250(2):277‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ohwada 1998 {published data only}

- Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Tanahashi Y, Nakamura S, Takeyoshi I, Ohya T, et al. Fibrin glue sandwich prevents pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy. World Journal of Surgery 1998;22(5):494‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Okada 2014 {published data only}

- Okada KI, Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, et al. Isolated Roux‐en‐Y anastomosis of the pancreatic stump in a duct‐to‐mucosa fashion in patients with distal pancreatectomy with en‐bloc celiac axis resection. Journal of Hepato‐biliary‐pancreatic Sciences 2014;21(3):193‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Okano 2008 {published data only}

- Okano K, Kakinoki K, Yachida S, Izuishi K, Wakabayashi H, Suzuki Y. A simple and safe pancreas transection using a stapling device for a distal pancreatectomy. Journal of Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreatic Surgery 2008;15(4):353‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oláh 2009 {published data only}

- Oláh A, Issekutz A, Belagyi T, Hajdu N, Romics L. Randomized clinical trial of techniques for closure of the pancreatic remnant following distal pancreatectomy. British Journal of Surgery 2009;96(6):602‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pannegeon 2006 {published data only}

- Pannegeon V, Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Vullierme M P, Kianmanesh R, Belghiti J. Pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: predictive risk factors and value of conservative treatment. Archives of Surgery 2006;141(11):1071‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ridolfini 2007 {published data only}

- Ridolfini MP, Alfieri S, Gourgiotis S, Miceli D, Rotondi F, Quero G, et al. Risk factors associated with pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy, which technique of pancreatic stump closure is more beneficial?. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2007;13(38):5096‐100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sa Cunha 2015 {published data only}

- Sa Cunha A, Carrere N, Meunier B, Fabre JM, Sauvanet A, et al. Stump closure reinforcement with absorbable fibrin collagen sealant sponge (TachoSil) does not prevent pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: The FIABLE multicenter controlled randomized study. American Journal of Surgery 2015;210(4):739‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Satoi 2013 {published data only}

- Satoi S, Yanagimoto H, Toyokawa H, Yamamoto T, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, et al. The beneficial impact of distal pancreatectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy on postoperative pancreatic fistula related complications. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. Elsevier Inc., 2013; Vol. 217, issue 3 Suppl:S19.

Sepesi 2012 {published data only}

Shankar 1990 {published data only}

- Shankar S, Theis B, Russell RC. Management of the stump of the pancreas after distal pancreatic resection. British Journal of Surgery 1990;77(5):541‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sheehan 2002 {published data only}

- Sheehan MK, Beck K, Creech S, Pickleman J, Aranha GV. Distal pancreatectomy: does the method of closure influence fistula formation?. American Journal of Surgery 2002;68(3):264‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sledzianowski 2005 {published data only}

- Sledzianowski JF, Duffas JP, Muscari F, Suc B, Fourtanier F. Risk factors for mortality and intra‐abdominal morbidity after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery 2005;137(2):180‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suc 2003 {published data only}

- Suc B, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Holmieres F, et al. Temporary fibrin glue occlusion of the main pancreatic duct in the prevention of intra‐abdominal complications after pancreatic resection: prospective randomized trial. Annals of Surgery. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (530 Walnut Street,P O Box 327, Philadelphia PA 19106‐3621, United States), 2003; Vol. 237, issue 1:57‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Suzuki 1995 {published data only}

- Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y, Morita A, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Kawamura T, et al. Fibrin glue sealing for the prevention of pancreatic fistulas following distal pancreatectomy. Archives of Surgery. First Department of Surgery, Kobe University School of Medicine, Japan., 1995; Vol. 130, issue 9:952‐5. [DOI] [PubMed]

Suzuki 1999 {published data only}

- Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Hori Y, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasonic dissector or conventional division in distal pancreatectomy for non‐fibrotic pancreas. British Journal of Surgery 1999;86(5):608‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Takeuchi 2003 {published data only}

- Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, Sekihara M, Hara T, Kori T, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: is staple closure beneficial?. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery 2003;73(11):922‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomay 2013 {published data only}