Abstract

Objective: Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the urinary bladder is associated with aggressive behavior and is typically treated with radical cystectomy. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) and its ligand Calcitriol have shown anti-tumor effects in various malignancies but to our knowledge there is no current information on VDR expression in bladder SCC. This study aimed to assess VDR immunostaining patterns in pure bladder SCC and its relation to the available clinicopathological parameters of such tumors.

Material and Methods: VDR immunostaining was performed on 35 radical cystectomy specimens from patients with primary pure SCC. Nuclear and cytoplasmic VDR staining was scored separately using the semi-quantitative immunoreactive score.

Results: Nuclear and cytoplasmic/membranous VDR expression was present in 35 (100%) and 19 (54.3%) cases, respectively, with a significant negative linear relationship (r=-0.33; p=0.035). Differences in cytoplasmic/membranous VDR expression were found in relation to tumor histology (p=0.018), tumor necrosis (p=0.022), and stage groups (p=0.001). Low cytoplasmic VDR correlated with increased tumor staging (Cc = -0.422), positive lymph node status (Cc = -0.375), and higher stage groups (Cc= -0.438). The median nuclear VDR expression score was significantly higher in advanced stage groups (p= 0.038).

Conclusion: Our data suggest that VDR may be a potential prognostic factor in bladder SCC. Further studies and clinical trials using vitamin D supplements may provide a new therapeutic option for those high-risk patients.

Keywords: VDR, Urinary bladder, Squamous cell carcinoma, Immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

According to GLOBOCAN data of 2020, bladder cancer is the 10th most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with higher incidence and mortality rates among men (1).

Primary pure squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a rare histologic variant of bladder cancer, accounting for 2-5% of all bladder cancer cases. Unfortunately, it is associated with more aggressive behavior and is often diagnosed at a later stage compared to the most common urothelial carcinoma (2).

There are two subtypes of bladder SCC, bilharzial-associated and non-bilharzial-associated. Both are traditionally treated with radical cystectomy (3) without neoadjuvant chemotherapy because SCC, unlike urothelial carcinoma, is unresponsive to cisplatin-based chemotherapy (4). Therefore, tumor biomarkers and new therapeutic targets for bladder SCC must be investigated to improve survival outcomes.

The active metabolite of Vitamin D (1,25(OH)2-VitD3 or Calcitriol) affects many cellular functions (5) through binding to the Vitamin D receptor (VDR), a transcriptional regulatory factor that is primarily localized to the nucleus of target cells (6). Upon ligand (Calcitriol) binding, VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoic X receptor. The heterodimer accumulates in the cell nucleus, where it regulates gene transcription via binding to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) in the promoter region of target genes. Transcriptional regulation can be either negative or positive depending on the specific VDRE sequences and the recruitment of co-activators or co-repressors (7,8).

Additionally, rapid non-genomic actions of 1,25(OH)2-VitD3 are mediated by plasma membrane-associated VDR. These actions include activation of several signaling pathways such as phosphatidylinositol-3’-kinase, phospholipase C, protein kinase C, and ion channels (9).

Calcitriol and its receptor VDR have antitumor effects as demonstrated by many experimental studies in different types of malignant tumors including bladder urothelial carcinoma (10,11). In tumor cells, Vitamin D is shown to induce apoptosis and cell differentiation. Also, it inhibits cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis (12) suggesting that active vitamin D3 and its analogues may reduce the risk of cancer development and/or serve as a potential therapeutic agent.

In the literature, several studies have investigated the role of VDR expression in SCC of different organs such as the oral cavity (13), esophagus (14), lung (15), and vulva (16). However, the information on VDR expression in bladder SCC is significantly lacking. Therefore, we aimed to analyze the VDR immunostaining pattern in patients with bladder SCC undergoing radical cystectomy and study its relation to the available clinicopathological parameters.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Case Selection

Radical cystectomy specimens from patients with primary pure bladder SCC (n=37) were retrospectively selected from the pathology lab of a specialized medical center from January 2019 to December 2022. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue blocks of the selected cases were retrieved from the archives. Two patients with unavailable tumor tissue blocks were excluded from further analysis. No patients had metastatic disease or received neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery.

The available clinical and pathological data of all patients (n=35) including age, sex, tumor stage, and nodal status were obtained from the pathology requests and reports. Patients’ names were removed and changed to numbers. This study was conducted after institutional ethical committee approval (FMBSUREC/02052023).

Histopathology

Tissue sections were cut from each FFPE block using a rotatory microtome at 4-5 µm thickness and were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain. Slides were reviewed to confirm tumor type, and grading was based on WHO classification of urinary and male genital tumors, 5th edition (17). The slides were also examined for the presence of vascular invasion, perineural invasion, bilharzial ova, and necrosis. Staging was performed according to the TNM system elaborated by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) (18).

VDR Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using anti-VDR antibody clone D6 (mouse monoclonal, diluted 1:200, Catalog number #MC0304RTU7, Medaysis, San Francisco Bay Area, USA). Sections 4 μm thick were dewaxed in xylene, dehydrated by an alcohol gradient, and then subjected to microwave heating for antigen retrieval. After incubation with the primary antibody for an hour at room temperature, sections were treated with the biotin-conjugated secondary antibody followed by the streptavidin biotin peroxidase complex. The reactions became visible after adding 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride. Slides were then counterstained in hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Negative controls were similarly prepared except for adding phosphate-buffered saline instead of the primary antibody. For positive control, skin tissue was used in each staining session.

VDR Immunohistochemical Evaluation

Positive Immunoreactivity was detected as brownish granules in the cell membrane/cytoplasm or nucleus. VDR expression was evaluated using the semi-quantitative immunoreactive score (IRS); the product of multiplying the scores for the percentage of positive cells and the staining intensity.

The percentage of cells expressing VDR in relation to the total number of tumor cells was scored as: 0 (<10% positive cells), 1 (11–30% positive cells), 2 (31–75% positive cells), and 3 (>75% positive cells). For staining intensity, a score of 0, 1, 2 and 3 was given for negative, weak, moderate, and strong brown staining, respectively. The final IRS was performed separately for cytoplasmic/membranous and nuclear expression in each tumor sample and the values ranged from 0 to 9. We then categorized VDR expression into negative (scores of 0 to 1), low (scores of 2 to 4), and high (scores of 6 to 9) (19).

Slides were examined under light microscopy (Olympus model BX53) by two independent authors who were blinded to all data. Images were obtained using a microscope slide scanner (APERIO LV1, Leica Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 25 (Armonk, New York: IBM Corp.), with a significant difference at p-value less than 0.05. Categorical variables were described in form of frequencies and percentages, whereas non-parametric continuous variables were described as the median (IQR). Data normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality, and then the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the differences between two unrelated groups in terms of continuous variables, The Kruskal-Wallis test for (k)-unrelated groups and the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to analyze the differences between two related samples in terms of continuous variables (VDR in cytoplasmic vs. nuclear expression). For categorical variables, the Chi-square (χ2) and Fisher’s exact (when more than 20% of cells have expected frequencies <5) tests were used. The cytoplasmic and nuclear expression scores were correlated with each other as well as with other variables using the Pearson correlation coefficient and Spearman’s rank correlation, respectively, with correlation coefficient (r) values ranging from −1 to +1.

RESULTS

Demographic and tumoral features

Out of the 35 patients, 27 were males with a 3.4:1 male to female ratio and median age of 62 (range: 52-78) years. Tumor size ranged from 4 to 8 cm (median: 5.5 cm). Most tumors were of moderate to high grade and the keratinizing-type (KSCC) was more prevalent (57.1%). Muscle invasion was detected among most of the studied tumors (91.4%). Sixty percent of patients presented with stage group IIIA-B. Further patient characteristics are listed in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the bladder squamous cell carcinoma patients.

|

Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

27 |

77.1 |

|

Female |

8 |

22.9 |

|

|

Age |

≤ 60 |

15 |

42.9 |

|

> 60 |

20 |

57.1 |

|

|

Tumor histology |

KSCC |

20 |

57.1 |

|

NKSCC |

15 |

42.9 |

|

|

Grade |

GI |

3 |

8.6 |

|

GII |

22 |

62.9 |

|

|

GIII |

10 |

28.6 |

|

|

Muscle invasion |

Absent |

3 |

8.6 |

|

present |

32 |

91.4 |

|

|

Tumor stage |

T1 |

3 |

8.6 |

|

T2 |

11 |

31.4 |

|

|

T3 |

17 |

48.6 |

|

|

T4 |

4 |

11.4 |

|

|

Bilharziasis |

Absent |

16 |

45.7 |

|

Present |

19 |

54.3 |

|

|

Necrosis |

Absent |

14 |

40.0 |

|

Present |

21 |

60.0 |

|

|

Lymphovascular invasion |

Negative |

25 |

71.4 |

|

Positive |

10 |

28.6 |

|

|

Perineural invasion |

Negative |

24 |

68.6 |

|

Positive |

11 |

31.4 |

|

|

Lymph node metastasis |

Negative |

25 |

71.4 |

|

Positive |

10 |

28.6 |

|

|

Nodal stage |

N0 |

25 |

71.4 |

|

N1 |

7 |

20.0 |

|

|

N2 |

3 |

8.6 |

|

|

Stage group |

I |

3 |

8.6 |

|

II |

11 |

31.4 |

|

|

IIIA |

18 |

51.4 |

|

|

IIIB |

3 |

8.6 |

|

KSCC: Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, NKSCC: Non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

Assessment of VDR expression

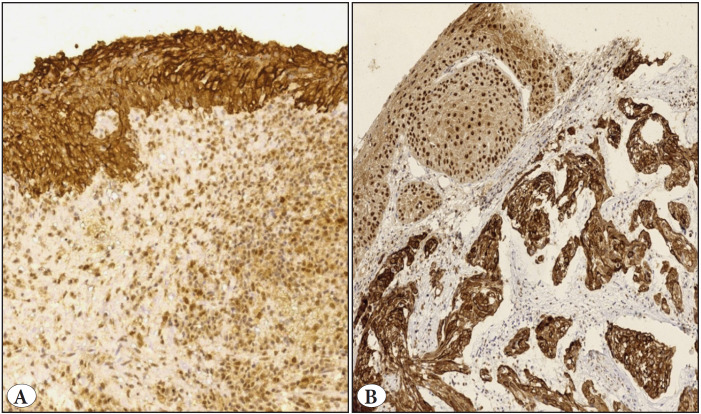

In this study, VDR expression was predominantly located in the cytoplasm and the cell membrane of the histologically normal urothelium, which was included in 10 cases (10/10). In contrast, areas of squamous metaplasia of the covering non-neoplastic urothelium seen in 15 cases showed only nuclear staining for VDR (15/15) Figure 1.

Figure 1.

VDR immunohistochemistry of apparently normal urothelium (A) shows diffuse strong cytoplasmic/membranous staining (Original magnification x200). B) VDR nuclear expression in metaplastic squamous epithelium, note cytoplasmic immunostaining in the underlying malignant squamous cells (Original magnification x100).

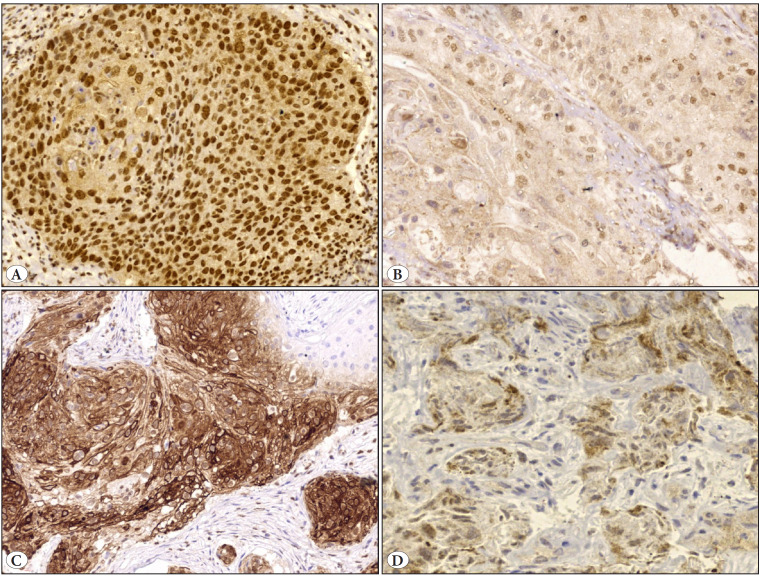

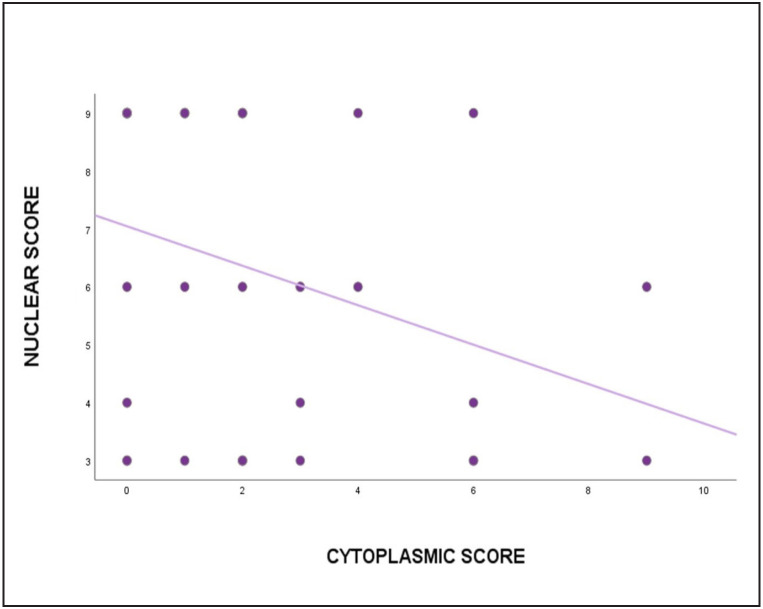

All tumors showed low or high nuclear immunostaining with no recorded negative cases. Cytoplasmic/membranous VDR expression was detected in tumor cells of 19 (54.3%) cases, and of these 37.1% showed low expression and 17.1% showed high expression. The median nuclear VDR expression was significantly (p<0.001) higher in bladder SCC as compared to the cytoplasmic/membranous VDR Table 2, Figure 2 with a significant negative linear correlation (r=-0.33; p=0.035) Figure 3.

Table 2.

VDR expression scores in the 35 studied cases.

|

Immunoreactive score (IRS) |

VDR expression |

||

|

Cytoplasmic/ membranous |

Nuclear |

||

|

Negative |

0 |

11 (31.4%) |

- |

|

1 |

5 (14.3%) |

- |

|

|

Low |

2 |

7 (20%) |

- |

|

3 |

4 (11.4%) |

10 (28.6%) |

|

|

4 |

2 (5.7%) |

3 (8.6%) |

|

|

High |

6 |

4 (11.4%) |

7 (20%) |

|

9 |

2 (5.7%) |

15 (42.9%) |

|

|

Median (IQR) |

2 (3) |

6 (6) |

|

|

P value |

<0.001* |

||

IQR: Interquartile range, *Statistical analysis by non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for related samples (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic scores)

Figure 2.

VDR immunostaining of bladder squamous cell carcinoma: A) Strong and diffuse nuclear staining. B) Weak nuclear staining. C) Strong cytoplasmic/membranous positivity. D) Low cytoplasmic expression (Original magnification A, B, C x200, D x400).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between nuclear and cytoplasmic VDR expression scores.

A high cytoplasmic VDR level was found in non-keratinizing tumors (p=0.018) and in those with absent necrosis (p=0.022). Cytoplasmic IRS significantly decreased with progressing AJCC stage groups (p=0.001). It was also lower in cases with positive lymph node metastasis (p=0.051). In contrast, nuclear IRS significantly increased in patients with advanced stage groups (p=0.038) Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of bladder SCC by nuclear and cytoplasmic VDR expression.

|

Characteristics |

n= 35 |

Cytoplasmic IRS |

Nuclear IRS |

|||||

|

Median |

IQR |

p-value |

Median |

IQR |

p-value |

|||

|

Sex(a) |

Male |

27 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

0.697 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

0.888 |

|

Female |

8 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

7.50 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Tumor histology(a) |

KSCC |

20 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

0.018* |

6.00 |

6.00 |

0.884 |

|

NKSCC |

15 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Grade(b) |

GI |

3 |

4.00 |

- |

0.836 |

9.00 |

- |

0.345 |

|

GII |

22 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

5.25 |

|||

|

GIII |

10 |

1.50 |

3.75 |

3.50 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Muscle invasion(a) |

Absent |

3 |

1.00 |

- |

0.989 |

9.00 |

0.00 |

0.057 |

|

present |

32 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Bilharziasis(a) |

Absent |

16 |

1.00 |

3.75 |

0.51 |

5.00 |

6.00 |

0.603 |

|

present |

19 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Necrosis(a) |

Absent |

14 |

2.00 |

5.25 |

0.022* |

6.00 |

5.25 |

0.662 |

|

present |

21 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

|||

|

LV-invasion(a) |

Negative |

25 |

2.00 |

3.50 |

0.65 |

6.00 |

5.50 |

0.952 |

|

Positive |

10 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

7.50 |

6.00 |

|||

|

Perineural invasion(a) |

Negative |

24 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

0.292 |

6.00 |

5.75 |

0.804 |

|

Positive |

11 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

|||

|

LN metastasis(a) |

Negative |

25 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

0.051 |

6.00 |

6.00 |

0.076 |

|

Positive |

10 |

0.00 |

2.25 |

9.00 |

3.75 |

|||

|

Stage group(a) |

(I - II) |

14 |

3.50 |

5.00 |

0.001* |

4.00 |

3.75 |

0.038* |

|

(IIIA-IIIB) |

21 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

9.00 |

4.50 |

|||

IRS: Immunoreactive score, IQR: Interquartile range, KSCC: keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, LN: lymph node, LV: lymphovascular, NKSCC: non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma

-Statistical analysis was conducted by (a) Mann-Whitney test, (b) Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA test, *statistically significant difference (p <0.05)

The cytoplasmic VDR expression score showed a statistically significant negative moderate correlation with T-stage, nodal status, and stage groups by Spearman’s analysis. However, the nuclear expression score did not correlate with the clinicopathological data Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation between cytoplasmic, nuclear VDR expression and clinicopathological variables.

|

Variables |

Cytoplasmic VDR expression |

Nuclear VDR expression |

||

|

p |

Correlation coefficient* |

p |

Correlation coefficient |

|

|

Age |

0.270 |

.192 |

0.943 |

0.012 |

|

Tumor size |

0.684 |

-0.071 |

0.748 |

-0.056 |

|

Tumor stage |

0.012 |

-0.422** |

0.115 |

0.271 |

|

Nodal stage |

0.027 |

-0.375** |

0.061 |

0.320 |

|

Stage groups |

0.009 |

-0.438*** |

0.095 |

0.287 |

*Spearman’s correlation analysis, ** Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level, *** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level, p two-tailed significance

DISCUSSION

Generally, urinary tract infection, Schistosomiasis, and other bladder irritants lead to chronic inflammation that is a major contributor to carcinogenesis of bladder SCC (17). Growth factors and cytokines released in chronic inflammation promote cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis, and inhibit apoptosis, resulting in squamous metaplasia, dysplasia, and invasive carcinoma (20).

Calcitriol has shown anti-inflammatory activities through inhibition of prostaglandin action, down regulation of p38 stress kinase, and nuclear factor KB signaling (21). Also, Calcitriol strongly inhibits cell proliferation in many human cancers including squamous cell carcinoma. The anti-proliferative effect depends on the levels of VDR (22) where mutations or deletion of VDR and the hydroxylase enzyme (CYP27B1) result in increased cell proliferation within the epidermal basal layer as well as defects in permeability barrier formation and the innate immune response (23).

In a clinical study, Calcitriol supplementation for 3 weeks before the surgical procedure in patients with head and neck SCC has prolonged the recurrence time (24). This highlights the role of Vitamin D as a potential novel, adjuvant cancer therapy with minimal side effects. To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe VDR expression exclusively in primary pure SCC of the urinary bladder.

Our results showed that there was more nuclear than cytoplasmic expression in all tumor samples with significant statistical difference. Similar findings were reported for different grades of cutaneous SCC (25), lung SCC (15,26), vulvar squamous carcinoma (16), and oral SCC (19). In contrast, Peng et al. found that VDR expression in esophageal SCC was predominantly localized to the cytoplasm and the cell membrane (14). In this study, increased nuclear VDR expression was accompanied by a decrease in cytoplasmic expression, displaying a significant inverse correlation. Yet, Czogalla et al. observed no correlation between nuclear and cytoplasmic VDR expression in epithelial ovarian carcinomas (27). It is worthy to mention that such a relationship is sparsely reported in the literature and may require further studies for confirmation.

Moreover, Nuclear VDR expression was observed in the metaplastic squamous epithelium seen near some tumors. This finding is compatible with the result reported by Menezes et al. for metaplastic lung biopsies (26).

Increased nuclear VDR expression in bladder SCC may be a sign for genomic pathways of vitamin D that control the abnormal growth, either metaplastic or neoplastic. However, cytoplasmic VDR may represent an adaptive mechanism for malignant cells. This may also point to increased sensitivity of tumor tissue to vitamin D activity.

Although nuclear VDR was predominant in patients’ tumor tissues, it showed only a significant statistical relationship with the AJCC stage groups (nuclear expression increased in more advanced tumors). This finding is in contrast to the result reported by Anand et al. where IRS significantly decreased with progressing anatomic stages in oral SCC cases (19). Srinivasan et al. and Del Puerto et al. found no significant correlation between nuclear VDR positivity and AJCC staging in lung cancer and cutaneous melanoma, respectively (15,28). We also observed a trend towards an increased expression of nuclear VDR in cases with metastatic lymph nodes versus those without nodal deposits. However, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.076).

In the present study, the cytoplasmic VDR level was found to be significantly lower in keratinizing-type SCCs and necrotizing tumors. When correlated with the AJCC anatomic stage/prognostic groups, cytoplasmic expression significantly decreased across the stages, indicating loss of VDR expression with increased tumor progression. Although statistically insignificant, a trend for decreased cytoplasmic VDR levels in tumors with poor differentiation, positive lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion was found.

It is difficult to compare the above results because no other studies on VDR expression in bladder SCC have been conducted yet. However, our findings are in line with previous studies on various types of cancers like esophageal carcinoma (14), cutaneous melanoma (28), and colorectal cancer (29). They reported that loss of cytoplasmic VDR expression is associated with differentiation and TNM stage. Different results were found by Czogalla et al. where high cytoplasmic VDR staining positively correlated with lymph node metastasis as well as a higher FIGO stage in cases of ovarian cancer (27). Others showed no association between cytoplasmic VDR and clinicopathological variables or the overall survival (15,16).

This discrepancy between studies can be explained by the different studied tumor types, different used VDR antibody clones, variable cut offs used for positivity, as well as polymorphisms in the VDR gene. However, the negative correlation between cytoplasmic VDR expression and tumor progression in some cancer types suggests VDR as a potential target of downregulation or ablation.

The small number of cases with pure bladder SCC seen in our center and the absence of their follow up data are the main limitations of our work.

CONCLUSION

The current study shows that VDR expression is present in histologically normal urothelium, squamous metaplasia, and invasive bladder SCC. Nuclear VDR expression is significantly higher in tumor samples than cytoplasmic VDR. Nuclear expression significantly increased in advanced tumor stages. Cytoplasmic VDR staining is inversely correlated with tumor staging, nodal status, and the AJCC stage groups, suggesting that loss of cytoplasmic VDR may be a prognostic factor for bladder SCC. Future large studies including clinical trials are recommended to prove our hypothesis that it may positively influence the patient management.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding has been received.

Ethics Approval

This study was conducted after Beni-Suef University ethical committee approval (FMBSUREC/02052023).

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation to the departmental chair, all colleagues, and technicians who helped us in this work.

References

- Sung Hyuna, Ferlay Jacques, Siegel Rebecca L., Laversanne Mathieu, Soerjomataram Isabelle, Jemal Ahmedin, Bray Freddie. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. May;2021 CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson Aaron, May Allison, Davaro Facundo, Raza Syed Johar, Siddiqui Sameer, Hamilton Zachary. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder: poor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Jun;2019 Int J Clin Oncol. 24:706–711. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Jeremy W., Carballido Estrella M., Ahmed Ahmed, Farhan Bilal, Dutta Rahul, Smith Cody, Youssef Ramy F. Squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Systematic review of clinical characteristics and therapeutic approaches. Sep;2016 Arab J Urol. 14:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porten Sima P., Willis Daniel, Kamat Ashish M. Variant histology: role in management and prognosis of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Sep;2014 Curr Opin Urol. 24:517–523. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi Sara, Johansson Harriet, Maisonneuve Patrick, Gandini Sara. Review and meta-analysis on vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and cancer risk. Jul;2009 Carcinogenesis. 30:1170–1180. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J. Wesley, Meyer Mark B., Bishop Kathleen A. Regulation of target gene expression by the vitamin D receptor - an update on mechanisms. Mar;2012 Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 13:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khammissa R. a. G., Fourie J., Motswaledi M. H., Ballyram R., Lemmer J., Feller L. The Biological Activities of Vitamin D and Its Receptor in Relation to Calcium and Bone Homeostasis, Cancer, Immune and Cardiovascular Systems, Skin Biology, and Oral Health. 2018Biomed Res Int. 2018:9276380–9276380. doi: 10.1155/2018/9276380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaberi Fatima A. H., Kongsbak-Wismann Martin, Aguayo-Orozco Alejandro, Krogh Nicolai, Buus Terkild B., Lopez Daniel V., Rode Anna K. O., Gravesen Eva, Olgaard Klaus, Brunak Søren, Woetmann Anders, Ødum Niels, Bonefeld Charlotte M., Geisler Carsten. Impaired Vitamin D Signaling in T Cells From a Family With Hereditary Vitamin D Resistant Rickets. 2021Front Immunol. 12:684015–684015. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.684015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle Daniel D. The Vitamin D Receptor as Tumor Suppressor in Skin. 2020Adv Exp Med Biol. 1268:285–306. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-46227-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konety B. R., Lavelle J. P., Pirtskalaishvili G., Dhir R., Meyers S. A., Nguyen T. S., Hershberger P., Shurin M. R., Johnson C. S., Trump D. L., Zeidel M. L., Getzenberg R. H. Effects of vitamin D (calcitriol) on transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in vitro and in vivo. Jan;2001 J Urol. 165:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Tingting, Guo Ying, Huang Zixian, Zhang Qianyu, Huang Zhuoshan, Zhang Yin, Huang Zhiquan. Vitamin D inhibits the proliferation of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by suppressing lncRNA LUCAT1 through the MAPK pathway. 2020J Cancer. 11:5971–5981. doi: 10.7150/jca.45389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon Sang-Min, Shin Eun-Ae. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Apr;2018 Exp Mol Med. 50:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm Martin, Cetindis Marcel, Biegner Thorsten, Lehman Max, Munz Adelheid, Teriete Peter, Reinert Siegmar. Serum vitamin D levels of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and expression of vitamin D receptor in oral precancerous lesions and OSCC. Mar;2015 Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 20:e188–195. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Yu J, Li F, Cui X, Chen Y. 2017Decreased vitamin D receptor protein expression is associated with the progression and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a multi-ethnic cohort study from the Xinjiang, China. 10:2340–2350. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan Malini, Parwani Anil V., Hershberger Pamela A., Lenzner Diana E., Weissfeld Joel L. Nuclear vitamin D receptor expression is associated with improved survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Jan;2011 J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 123:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehin D, Haugk C, Thill M, Cordes T, William M, Hemmerlein B, Friedrich M. uuuuVitamin D receptor expression in patients with vulvar cancer. 32:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordetsky JB, Gakis G, Hansel DE, Menon S, Osunkoya AO, Tomlins SA. Urinary and male genital tumors. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon (France): Pure squamous carcinoma of the urothelial tract; pp. 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Amin MB, Edge S, Greene S, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, Jessup JM, Brierley JD, Gaspar LE, Schilsky RL, Balch CM. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer International Publishing; New York: [Google Scholar]

- Anand Akshay, Singh Suyash, Sonkar Abhinav A., Husain Nuzhat, Singh Kul Ranjan, Singh Sudhir, Kushwaha Jitendra K. Expression of vitamin D receptor and vitamin D status in patients with oral neoplasms and effect of vitamin D supplementation on quality of life in advanced cancer treatment. 2017Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 21:145–151. doi: 10.5114/wo.2017.68623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef Ramy, Kapur Payal, Kabbani Wareef, Shariat Shahrokh F., Mosbah Ahmed, Abol-Enein Hassan, Ghoniem Mohamed, Lotan Yair. Bilharzial vs non-bilharzial related bladder cancer: pathological characteristics and value of cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Jul;2011 BJU Int. 108:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi Nazanin, Ahmadian Elham, Shahi Shahriar, Roshangar Leila, Khan Haroon, Kouhsoltani Maryam, Maleki Dizaj Solmaz, Sharifi Simin. Role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor (VDR) in oral cancer. Jan;2019 Biomed Pharmacother. 109:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo Alejandro A., Deeb Kristin K., Pike J. Wesley, Johnson Candace S., Trump Donald L. Dexamethasone enhances 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 effects by increasing vitamin D receptor transcription. Oct;2011 J Biol Chem. 286:36228–36237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle Daniel D., Oda Yuko, Tu Chia-Ling, Jiang Yan. Novel mechanisms for the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in the skin and in skin cancer. Apr;2015 J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 148:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari Shri, Vasudevan Vijeev, Kasibhotla Soundarya, Reddy Deepa, Venkatappa Manjunath, Devaiah Devaraju. Anti‐inflammatory Dietary Supplements in the Chemoprevention of Oral Cancer. Sep;2016 Cancer Res Front. 2:380–395. doi: 10.17980/2016.380. http://cancer-research-frontiers.org/2016-2-380/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reichrath Jörg, Rafi Leyla, Rech Martin, Mitschele Tanja, Meineke Viktor, Gärtner Barbara C., Tilgen Wolfgang, Holick Michael F. Analysis of the vitamin D system in cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. Mar;2004 J Cutan Pathol. 31:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes Ravi J., Cheney Richard T., Husain Aliya, Tretiakova Maria, Loewen Gregory, Johnson Candace S., Jayaprakash Vijay, Moysich Kirsten B., Salgia Ravi, Reid Mary E. Vitamin D receptor expression in normal, premalignant, and malignant human lung tissue. May;2008 Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 17:1104–1110. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czogalla Bastian, Deuster Eileen, Liao Yue, Mayr Doris, Schmoeckel Elisa, Sattler Cornelia, Kolben Thomas, Hester Anna, Fürst Sophie, Burges Alexander, Mahner Sven, Jeschke Udo, Trillsch Fabian. Cytoplasmic VDR expression as an independent risk factor for ovarian cancer. Oct;2020 Histochem Cell Biol. 154:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00418-020-01894-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Puerto C., Navarrete-Dechent C., Molgó M., Camargo C. A., Borzutzky A., González S. Immunohistochemical expression of vitamin D receptor in melanocytic naevi and cutaneous melanoma: a case-control study. Jul;2018 Br J Dermatol. 179:95–100. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Qi, Han Xue-Ping, Yu Jie, Peng Hao, Chen Yun-Zhao, Li Feng, Cui Xiao-Bin. Decreased vitamin D receptor protein expression is associated with progression and poor prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. 2020Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 13:746–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]