Abstract

The peptide transport protein DtpT of Lactococcus lactis was purified and reconstituted into detergent-destabilized liposomes. The kinetics and substrate specificity of the transporter in the proteoliposomal system were determined, using Pro-[14C]Ala as a reporter peptide in the presence of various peptides or peptide mimetics. The DtpT protein appears to be specific for di- and tripeptides, with the highest affinities for peptides with at least one hydrophobic residue. The effect of the hydrophobicity, size, or charge of the amino acid was different for the amino- and carboxyl-terminal positions of dipeptides. Free amino acids, ω-amino fatty acid compounds, or peptides with more than three amino acid residues do not interact with DtpT. For high-affinity interaction with DtpT, the peptides need to have free amino and carboxyl termini, amino acids in the l configuration, and trans-peptide bonds. Comparison of the specificity of DtpT with that of the eukaryotic homologues PepT1 and PepT2 shows that the bacterial transporter is more restrictive in its substrate recognition.

Studies of the transport of peptides across the cell membrane of Lactococcus lactis have established that the organism uses at least three distinct peptide transport systems (5, 17, 20, 21, 32, 35, 36; Y. Sanz Herranz, F. C. Lanfermeijer, W. N. Konings, and B. Poolman, submitted for publication). In addition to the ATP-dependent ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type of oligo- and di- and/or tripeptide transport systems, Opp and DtpP, respectively, L. lactis possesses a proton motive force-driven di- and/or tripeptide transporter DtpT. This transporter catalyzes the uptake of di- and tripeptides in symport with a proton(s) and belongs to the peptide transport (PTR) family (39). This family includes, among others, the PTR proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PTR2) (31), Candida albicans (CaPTR2) (1), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtPTR2A and AtPTR2B) (37, 38), rabbit intestine (rbPepT1) (10), and human intestine (hPepT1) (22).

Considering the wide distribution of the PTR family of solute transporters throughout nature, the identification of the structure determinants of the substrates is of technological and pharmacological importance. The substrate specificity of members of this family of PTRs has been most extensively studied for the mammalian intestinal and renal peptide transporters (PepT1 and PepT2) (4, 6, 7). These studies indicated that for interaction with the carrier protein the following structure properties of the peptides were required: (i) free amino- and carboxyl-termini, (ii) an amino group and peptide bond nitrogen located in the α-position, (iii) trans configuration of the peptide bond, (iv) l-α-amino acid isomers at both the amino- and carboxyl-termini, and (v) a backbone length of less than four amino acid residues (4, 23).

In the present study, we have analyzed the kinetics and the substrate specificity of the bacterial peptide transporter, DtpT, in proteoliposomes using Pro-[14C]Ala as reporter peptide. The inhibition constants (IC50) were determined for peptides with different side chains at the first, second, or third position and/or configurations of the peptide backbone, as well as for peptide mimetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material.

All peptides were composed of l-amino acids unless otherwise stated. [14C]alanine was obtained from Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom. Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin was from Qiagen, Inc., Hilden, Germany. Decyl-β-d-maltoside (DM) and n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) were from Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland. Bio Beads SM2 were from Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif. Total Escherichia coli lipids and l-α-phosphatidylcholine from egg yolk were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Ala. All other materials were reagent grade and were obtained from commercial sources. Prolyl-[14C]alanine was synthesized from [14C]alanine plus unlabeled N-butyloxycarbonylproline as described previously (18).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

L. lactis/pGKHT was grown at 29°C in M17 medium (Difco) or in chemically defined medium (21) at pH 6.5, supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose plus erythromycin (5 mg/ml) as previously described (18).

Isolation of membrane vesicles.

For the isolation of right-side-out membrane vesicles of L. lactis, cells were lysed as previously described (24). Inside-out membrane vesicles were isolated as previously described (33) with the following modifications: the cell wall was digested with 10 mg of lysozyme per ml, the cells were broken by a twofold passage through a French pressure cell at 20,000 lb/in2, and DNase was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. The membrane preparations were stored in liquid nitrogen.

Solubilization and purification.

The membranes were solubilized by DDM after preextraction of the membrane vesicles with octaethylene glycol monodecyl ether (C10E8) as described previously (9) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (∼4 mg of DtpT/ml of resin), which was equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 8.0], containing 400 mM sodium chloride and 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) plus 0.1% DDM (buffer B). The column material was poured into a Bio-Spin column (Bio-Rad) and washed consecutively with 5 column volumes of buffer B, buffer B plus 5 mM imidazole, and buffer B plus 15 mM imidazole with the sodium chloride concentration lowered to 200 mM. The protein was eluted with 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0), 200 mM sodium chloride, and 200 mM imidazole plus 0.1% DM. The purification was carried out at 4°C with sterile solutions.

Membrane reconstitution.

The purified DtpT protein was reconstituted into preformed liposomes, prepared from acetone-ether-washed E. coli lipids and l-α-phosphatidylcholine from egg yolk in a ratio of 3:1 (wt/wt) as previously described (19) with the following modifications: the liposomes were equilibrated with 4.1 mM DM for 45 min on ice, and purified DtpT was added at a protein-to-lipid ratio of 1:100 (wt/wt). The mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature under gentle agitation. For the removal of detergent, polystyrene beads (Bio Beads SM2; Bio-Rad) were added at a wet weight of 40 mg/ml and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Fresh Bio Beads were added twice, and the samples were incubated at 4°C for 2 h and overnight, respectively. The proteoliposomes were washed with 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, harvested by centrifugation (280,000 × g for 15 min) and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Transport assays.

Artificially imposed ion-diffusion potentials were generated as previously described (12). Proteoliposomes were resuspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0), 100 mM potassium acetate (KAc), and 2 mM MgSO4 and frozen in 0.5-ml aliquots in liquid nitrogen. After the samples were thawed at room temperature, the proteoliposomes were extruded 11 times through a 400-nm polycarbonate filter to obtain unilamellar liposomes of relatively homogenous size (19). Subsequently, aliquots of concentrated membrane suspensions (1 mg of protein/ml) were diluted 50-fold into 120 mM Na-PIPES [piperazine-N-N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] (pH 6.0), containing 2 mM MgSO4, 0.5 μM valinomycin, and Pro-[14C]Ala at varying concentrations. The uptake was assayed at different time intervals at 30°C, after which the reaction was stopped by diluting the reaction mixture with 2 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M LiCl. The proteoliposomes were collected on 0.45-μm cellulose nitrate filters and washed once more with 2 ml of the LiCl solution. The data analysis was carried out as described previously (5).

Protein determination.

Protein concentrations were determined with the Lowry protein assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The concentration and stability of purified DtpT was determined by measuring the absorption spectrum of the sample between 240 and 340 nm on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 1.371 (mg/ml)−1 cm−1 for DtpT.

RESULTS

Transport kinetics of membrane-reconstituted DtpT protein.

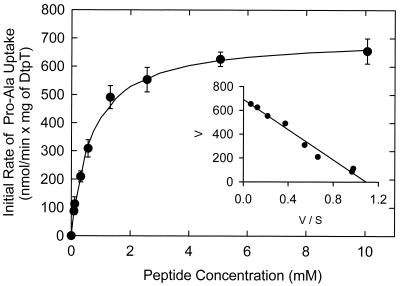

The kinetics of proton motive force-driven Pro-[14C]Ala uptake was determined from initial rate measurements at peptide concentrations of 5μm to 12.5 mM (Fig. 1). The apparent affinity constant (Km) was 0.66 ± 0.04 mM, and the maximal rate of uptake (Vmax) was 0.70 ± 0.1 μmol/min × mg of protein (mean ± standard error of three determinations).

FIG. 1.

Kinetic analysis of proton-driven uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala. Proteoliposomes preloaded with 20 mM KPi, 100 mM KAc, and 2 mM MgSO4 (pH 6.0) were diluted 50-fold into 120 Na-PIPES, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.5 μM valinomycin (pH 6.0), plus Pro-[14C]Ala at concentrations ranging from 0.065 to 10 mM. The inset shows the Eadie-Hofstee transformation of the data; V is the rate of Pro-Ala uptake (in nanomoles per minute per milligram of protein) and S is the millimolar concentration of Pro-Ala in the medium.

Inhibition constants for peptides with different length and composition.

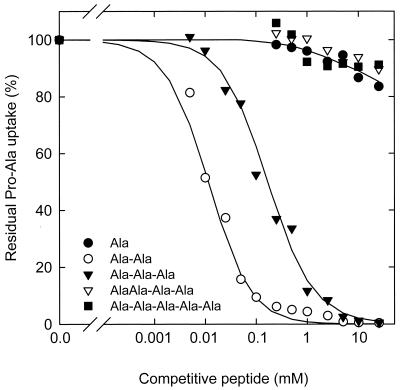

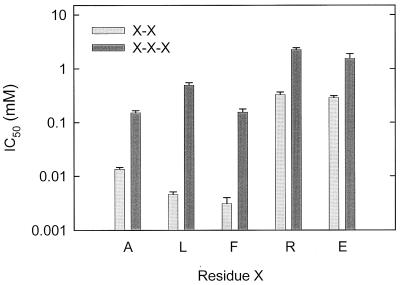

To determine the size exclusion limits of DtpT, the inhibition of Pro-[14C]Ala uptake was measured in the presence of Ala, Gly, or alanine- or glycine-containing peptides (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The results indicate that free amino acids and peptides with more than three residues did not significantly inhibit Pro-Ala uptake. Di- and tripeptides inhibited Pro-Ala uptake, and DtpT had an approximately 10-fold higher affinity for di-Ala (IC50, 13.5 ± 1.1 μM) than for tri-Ala (IC50, 152 ± 15 μM). The difference in affinity was even larger for Gly-Gly (IC50, 145 ± 15 μM) and Gly-Gly-Gly (IC50, 9.0 ± 1.3 mM). To establish whether DtpT has in general the highest affinity for dipeptides, we also studied the inhibition of Pro-Ala uptake by di- and tripeptides composed of amino acids of different molecular size, hydrophobicity, and/or charge. Figure 3 shows that no matter the property of the peptide, dipeptides always display a higher affinity than the analogous tripeptides. The highest affinities are observed for hydrophobic dipeptides.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of Pro-[14C]Ala uptake by Ala and Ala-containing peptides. Uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala (65 μM, final concentration) was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1, in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of alanine and alanine-containing peptide series (0.01 to 10 mM). Uptake of Pro-Ala measured in the absence of inhibitors was taken as 100% (46 nmol/min × mg of protein). Symbols: ●, alanine; ○, Ala-Ala; ▾, Ala-Ala-Ala; ▿, Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala; ■, Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of Pro-Ala uptake by amino acids and peptidesa

| Amino acid and peptide | IC50 (mM) |

|---|---|

| Gly | >50 |

| Gly-Gly | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| Gly-Gly-Gly | 9.0 ± 1.3 |

| Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly | >50 |

| Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly-Gly | >50 |

| Ala | >30 |

| Ala-Ala | 0.014 ± 0.001 |

| Ala-Ala-Ala | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala | >30 |

| Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala | >30 |

The IC50 values were derived from plots similar to that shown in Fig. 2, using 65 μM Pro-[14C]Ala and different concentrations of amino acids or peptides. At time zero, proteoliposomes in 20 mM KPi, 100 mM KAc, and 2 mM MgSO4 (pH 6.0) were diluted 50-fold into 120 mM Na-PIPES and 2 mM MgSO4 (pH 6.0) plus 0.5 μM valinomycin, and the transport reaction was terminated after 45 s; values are the averages of two measurements. The standard error is given for each value.

FIG. 3.

IC50 values for dipeptides and tripeptides. Uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala (65 μM, final concentration) was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1 in the presence of various competing peptides. The IC50 values for different inhibitors were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. The error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means of two independent experiments.

Inhibition constants for peptides with variation in either the N- or C-terminal amino acid residue.

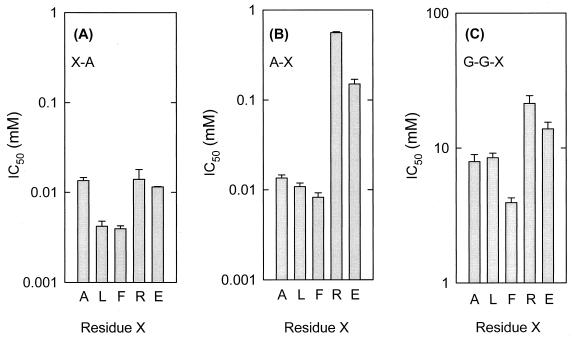

The effects of variations in the amino-terminal residue of the dipeptide X-Ala on IC50 were determined. The IC50 values were lowest when the amino-terminal residue was hydrophobic (Fig. 4A). The same trend was true for Ala-X peptides when the carboxyl-terminal residue was varied (Fig. 4B). The IC50 values for Ala-Ala, Ala-Leu, and Ala-Phe were almost 80-fold lower than that for Ala-Arg and approximately 20-fold lower than that for Ala-Glu. Similar effects were observed when the carboxyl-terminal position of the tripeptide Gly-Gly-X was varied (Fig. 4C). Thus, DtpT seems to display the highest affinity for hydrophobic peptides, and at every position the preferred residues follow the order Phe > Leu > Ala > Glu > Arg.

FIG. 4.

IC50 values for peptides differing at the amino- or carboxyl-terminal residue. Uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala (65 μM, final concentration) was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1 in the presence of various competing peptides. The IC50 values for different inhibitors were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. X corresponds to the variable amino acid at position 1 (A), 2 (B), and 3 (C). The error bars indicate the standard deviations from the means of two independent experiments.

Stereospecificity.

To study the stereospecificity of DtpT, the IC50 values of dipeptides with l- or d-alanine residues were determined (Table 2). Substitution of the N-terminal l-Ala for the d-isomer in l-Ala–l-Ala resulted in a 2,000-fold reduction in affinity. When the C-terminal l-Ala residue was replaced by the d-isomer, a 200-fold reduction in affinity was observed. As anticipated, the IC50 value was highest for d-Ala–d-Ala.

TABLE 2.

Effect of peptide modification and configuration on the ligand affinity of DtpTa

| Peptide (analog) | IC50 (mM) |

|---|---|

| l- or d-amino acid residue | |

| Ala-Ala | 0.014 ± 0.001 |

| D-Ala-Ala | 28.7 ± 2.8 |

| Ala-D-Ala | 2.76 ± 0.55 |

| D-Ala-D-Ala | >50 |

| Blocking of the N- or C-terminal group | |

| Phe-Phe | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| Ac-Phe-Phe | 15.4 ± 2.4 |

| Pro-Ala | 0.62 ± 0.10 |

| Z-Pro-Ala | 16.8 ± 3.6 |

| Gly-Gly | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| Gly-Gly-NH2 | 16.0 ± 2.7 |

| Gly-Gly-OEt | 11.9 ± 1.2 |

| Secondary amino group and configuration of the peptide bond | |

| Ala-His | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| β-Ala-His | >30 |

| Ala-Pro | 0.08 ± 0.03 |

| Gly-Sar | 6.6 ± 0.6 |

| N-terminal carbobenzoxy group | |

| Phe | >30 |

| Z-Phe | 2.52 ± 0.59 |

| Z-Phe-Phe | 0.69 ± 0.06 |

| Phe-Phe-Phe | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| Z-Phe-Phe-Phe | 3.49 ± 0.49 |

Experimental conditions are the same as described in the footnote to Table 1.

Effect of blocking the N- and C-terminal groups.

To analyze whether a free amino- or carboxyl-terminus is important for interaction with DtpT, various dipeptides with either a blocked amino or carboxyl group were tested (Table 2). In all cases, when the N or C terminus was blocked the affinity was seriously reduced, but significant inhibition by the peptide analogue was still observed.

Importance of the secondary amino group and modification of the peptide bond.

The importance of a free amino group was analyzed by comparing the relative affinity of β-Ala-His with that of the corresponding α-amino dipeptide (Table 2). The dipeptide with the amino group in the α position had much higher (over 100-fold) affinity than the dipeptide with the amino group in the β position. Also, peptides with an imino group, such as Pro-Ala and Ala-Pro, exhibited relatively low affinity when compared with Ala-Ala. When the peptide bond nitrogen was modified, e.g., by replacement of the hydrogen by a CH3 group, as in Gly-Sar, the affinity dropped 50-fold with respect to that of Gly-Gly.

Peptides with N-terminal carbobenzoxy group.

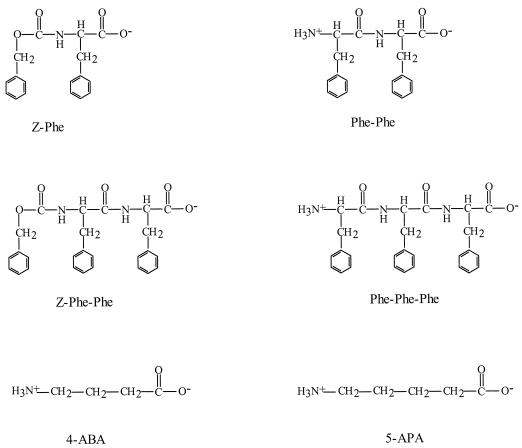

To determine whether some amino acid mimetics could substitute for amino acids (Fig. 5), we compared the IC50 value of Phe-containing peptides with those that had a carbobenzoxy (Z) group at the first position (Table 2). Z-Phe displayed significant affinity (IC50, 2.5 ± 0.6 mM), which suggests that the Z group can substitute the amino-terminal residue. The carbobenzoxy groups at the amino-terminal end of di- and tripeptides reduced the affinity. A 200-fold reduction in affinity was observed when Z-Phe-Phe was compared with Phe-Phe, but the reduction in affinity was only 4- to 5-fold when compared with Phe-Phe-Phe. Overall, these results indicate that carbobenzoxy group partially mimics the amino-terminal amino acid.

FIG. 5.

Structures of phenylalanine-containing peptides and those with a carbobenzoxy group at the first position; the structure of the peptide mimetics 4-amino-butanoic acid and 5-amino-pentanoic acid are also shown.

ω-Amino fatty acid compounds.

A zwitterionic amino acid group separated by a distinct molecular distance is one of the most important features of substrates of the mammalian peptide transporters (7). The interaction of DtpT with ω-amino fatty acids (Fig. 5), which possess an N-terminal amino group and a C-terminal carboxyl group and a hydrocarbon rather than a peptide backbone, was studied. No significant inhibition of Pro-[14C]Ala uptake was observed when either 4-amino-butanoic acid, 5-amino-pentanoic acid, 6-amino-hexanoic acid, 7-amino-heptanoic acid, or amino-octanoic acid was used up to a concentration of 50 mM.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide evidence for a number of important findings with regard to the substrate specificity of DtpT. We stress that the specificity data are obtained from measurements in which the peptide or peptide analogue competes with the uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala. Inhibition of Pro-[14C]Ala uptake does not necessarily imply that the tested substrate is indeed transported by DtpT. The following can be concluded. (i) The affinities of peptides tested vary from μM to mM. (ii) Free amino- and carboxyl-termini are both important but not sufficient for high affinity interaction with DtpT. (iii) An amino-group and peptide-bond nitrogen located in the α-position is important for high-affinity interaction. (iv) Peptides with a trans peptide bond interact with a higher affinity than those that are in the cis configuration. (v) The highest affinity is observed with l-α-amino acid isomers at both amino and carboxyl termini. (vi) Hydrophobic amino acids located at the P1 position of the dipeptide increase the affinity. (vii) Charged amino acids located at the P2 position of a dipeptide or tripeptide have a decreased affinity. (viii) Charged amino acids located at the P3 position of tripeptides decrease the affinity. (ix) Dipeptides have a higher affinity than analogous tripeptides. (x) Hydrophobic peptides display a higher affinity than hydrophilic peptides. (xi) In most cases, cationic peptides have a significantly lower affinity than neutral or anionic substrates. (xii) Phe or Phe-containing di- or tri-peptides with a carbobenzoxy group at the amino terminus compete effectively with the uptake of Pro-[14C]Ala. (xiii) Free amino acids or peptides with a backbone of more than three amino acid residues are not accepted as substrates. (xiv) ω-Amino fatty acid compounds are not substrates of the DtpT system.

The substrate specificity of members of the family of peptide transporters is best known for the mammalian intestinal and renal peptide transporters PepT1 and PepT2. Although PepT1 and PepT2 have only about 50% identity in amino acid sequence, both transporters have a similar specificity pattern and transport almost all possible dipeptides, tripeptides, and numerous peptidomimetics. The main difference between these two peptide transporters is that PepT2 has a different recognition pattern for β-lactam antibiotics, a higher structure restriction of certain substrates, and overall a higher affinity than PepT1 (2–4, 6, 7, 13, 14, 41). From a comparison of our data with that of the mammalian transporters, it is apparent that DtpT is more restrictive in its specificity than PepT1 or PepT2: (i) unlike Pep T1, DtpT does not accept ω-amino fatty acids as substrates; (ii) in contrast to PepT2, the affinity of DtpT is not reduced when a basic or acidic amino acid replaces a neutral residue at the N-terminal position; (iii) DtpT is more selective for l-isomers at the N-terminal position than PepT2; and (iv) DtpT is more selective for dipeptides than for tripeptides, whereas PepT2 has very similar affinities for both.

The most extensively studied peptide transporters in prokaryotes are those of E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. These gram-negative bacteria contain at least three peptide transport systems with different but overlapping specificities. The Opp system, which belongs to the ABC superfamily, can transport a wide variety of natural or modified peptide substrates composed of two to five amino acids (16, 25–27, 40). Translocation of longer peptides in gram-negative bacteria may be restricted by the upper size exclusion limits of the outer membrane pores and is not a property of the system itself (29). Such a limitation is not present in gram-positive bacteria; for instance, Opp of the gram-positive bacterium L. lactis can facilitate the uptake of peptides of up to 18 amino acid residues (5, 20). This property has been further confirmed by binding studies which indicate that OppA, the peptide binding subunit of Opp, could bind peptides with at least 12 amino acid residues (21). Our studies indicate that there are no common properties shared with this class of peptide transport systems, as DtpT interacts with peptides which are not longer than three amino acid residues.

The second peptide transport system (Tpp) of E. coli has been shown to transport a wide variety of tripeptides; the system appears to be less effective in the uptake of dipeptides. Its mechanism of energy coupling to transport and structure are not known, and it is not clear whether or not Tpp belongs to the ABC superfamily (like Opp) or to a family of secondary transport proteins (like DtpT). Tpp shows similarities to the Opp system in its requirement for a positively charged amino terminus and its ability to transport peptides without a free C-terminal carboxyl group (15, 29). Similar to Tpp of E. coli, the DtpT system of L. lactis has higher affinities for hydrophobic di- and tripeptides (11; Sanz Harranz et al., submitted). The DtpT system of L. lactis has fundamentally different properties in substrate specificity: the preferred substrates are dipeptides, the amino-terminal residue does not have to be charged, a charged residue at carboxyl-terminus drastically reduces the affinity, and free N- and C-terminal groups are both important for interaction with the protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frank C. Lanfermeijer, Frank J. M. Detmers, Yolanda Sanz Herranz, Antonia Picon, Edmund R. S. Kunji, and Anja Hagting for valuable comments.

This work was supported by grants from the European Union (BIO-4-CT-960016 and BIO-4-CT-960129) and the Ubbo-Emmius Foundation of the University of Groningen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basrai M A, Lubkowitz M A, Perry J R, Miller D, Krainer E, Naider F, Becker J M. Cloning of a Candida albicans peptide transport gene. Microbiology. 1995;141:1147–1156. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Börner V, Fei Y J, Hartrodt B, Ganapathy V, Leibach F H, Neubert K, Brandsch M. Transport of amino acid aryl amides by the intestinal H+/peptide cotransport system, PEPT1. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:698–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X Z, Zhu T, Smith D E, Hediger M A. Stoichiometry and kinetics of the high-affinity H+-coupled peptide transporter PepT2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2773–2779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniel H, Morse E L, Adibi S A. Determinants of substrate affinity for the oligopeptide/H+ symporter in the renal brush border membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9565–9573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detmers F J M, Kunji E R S, Lanfermeijer F C, Poolman B, Konings W N. Kinetics and specificity of peptide uptake by the oligopeptide transport system of Lactococcus lactis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16671–16679. doi: 10.1021/bi981712t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Döring F, Michel T, Rösel A, Nickolaus M, Daniel H. Expression of the mammalian renal peptide transporter PEPT2 in the yeast Pichia pastoris and applications of the yeast system for functional analysis. Mol Membr Biol. 1998;15:79–88. doi: 10.3109/09687689809027522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Döring F, Amasheh J W, Clauss W, Ahlbrecht H, Daniel H. Minimal molecular determinants of substrates for recognition by the intestinal peptide transporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23211–23218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunten P, Mowbray S L. Crystal structure of the dipeptide binding protein from Escherichia coli involved in active transport and chemotaxis. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2327–2334. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang G, Friesen R, Lanfermeijer F, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings W N. Manipulation of activity and orientation of membrane-reconstituted di-tripeptide transport protein DtpT of Lactococcus lactis. Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16:297–304. doi: 10.1080/096876899294517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fei Y J, Kanai Y, Nussberger S, Ganapathy V, Leibach F H, Romero M F, Singh S K, Boron W F, Hediger M A. Expression cloning of a mammalian proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter. Nature. 1994;368:563–566. doi: 10.1038/368563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foucaud C, Kunji E R S, Hagting A, Richard J, Desmazeaud M, Poolman B. Specificity of peptide transport system in Lactococcus lactis: evidence for a third system which transports hydrophobic di- and tripeptides. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4652–4657. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4652-4657.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foucaud C, Poolman B. Lactose transport protein of Streptococcus thermophilus. Functional reconstitution of the protein and characterization of the kinetic mechanism of transport. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22087–22094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganapathy M E, Brandsch M, Prasad P D, Ganapathy V, Leibach F H. Differential recognition of β-lactam antibiotics by intestinal and renal peptide transporters, PEPT1 and PEPT2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25672–25677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganapathy M E, Huang W, Wang H, Ganapathy V, Leibach F H. A substrate for the intestinal and renal peptide transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:470–475. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson M M, Price M, Higgins C F. Genetic characterization and molecular cloning of the tripeptide permease (tpp) genes of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:122–130. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.122-130.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyer C A, Morgan D G, Staros J V. Binding specificity of the periplasmic oligopeptide-binding protein from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:775–779. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.775-779.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagting A, Kunji E R S, Leenhouts K J, Poolman B, Konings W N. The di- and tripeptide transport protein of Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11391–11399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagting A, Knol J, Hasemeier B, Streutker M R, Fang G, Poolman B, Konings W N. Amplified expression, purification and functional reconstitution of the di- and tripeptide transport protein of Lactococcus lactis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knol J, Veenhoff L, Liang W J, Henderson P J F, Leblanc G, Poolman B. Unidirectional reconstitution into detergent destabilized liposomes of the purified lactose transport system of Streptococcus thermophilus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15358–15366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunji E R S, Fang G, Jeronimus-Stratingh C M, Bruins A P, Poolman B, Konings W N. Reconstruction of the proteolytic pathway for utilization of β-casein by Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1107–1118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanfermeijer F C, Picon A P, Konings W N, Poolman B. Kinetics and consequences of binding of nona- and dodecapeptide to the oligopeptide binding protein (OppA) of Lactococcus lactis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14440–14450. doi: 10.1021/bi9914715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang R, Fei Y-J, Prasad P D, Ramamoorthy S, Han H, Yang-Fang T L, Hediger M A, Ganapathy V, Leibach F H. Human intestinal H+/peptide cotransporter. Cloning, functional expression, and chromosomal localization. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6456–6463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lister N, Sykes A P, Bailey P D, Boyd C A R, Bronk J R. Dipeptide transport and hydrolysis in isolated loops of rat small intestine: effects of stereospecificity. J Physiol. 1995;484:173–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otto R, Lageveen R G, Veldkamp H, Konings W N. Lactate-efflux induced potential in membrane vesicles of Streptococcus cremoris. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:733–738. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.733-738.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne J W. The requirement for the protonated α-amino group for the transport of peptides in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1971;123:245–253. doi: 10.1042/bj1230245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne J W. Peptide transport in Escherichia coli: permease specificity towards terminal amino group substituents. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;80:269–276. doi: 10.1099/00221287-80-1-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne J W, Bell G. Direct determination of the properties of peptide transport systems in Escherichia coli using a fluorescent labeling procedure. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:447–455. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.447-455.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Payne J W, Gilvarg C. The role of the terminal carboxyl group in peptide transport in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Payne J W, Smith M W. Peptide transport by microorganisms. Adv Microb Physiol. 1994;36:1–80. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry D, Gilvarg C. Spectrophotometric determination of affinities of peptides for their transport systems in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:943–948. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.943-948.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry J R, Basrai M A, Steiner H-Y, Naider F, Becker J M. Isolation and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae peptide transport gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:104–115. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picon A, Kunji E R S, Lanfermeijer F C, Konings W N, Poolman B. Specificity mutants of the binding protein of the oligopeptide transport system of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1600–1608. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1600-1608.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poolman B, Konings W N, Robillard G T. The location of redox-sensitive groups in the carrier protein of proline at the outer and inner surface of the membrane of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1983;135:41–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poolman B, Konings W N. Relation of growth of Streptococcus lactis and Streptococcus cremoris to amino acid transport. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:700–707. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.700-707.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smid E J, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Mechanism and energetics of dipeptide transport in membrane vesicles of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:292–298. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.292-298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smid E J, Plapp R, Konings W N. Peptide uptake is essential for growth of Lactococcus lactis on the milk protein casein. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6135–6140. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6135-6140.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song W, Steiner H Y, Zhang L, Stacey G, Becker J M. Cloning of a second Arabidopsis peptide transport gene. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:171–178. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner H Y, Song W, Zhang L, Naider F, Becker J M, Stacey G. An Arabidopsis peptide transporter is a member of a new class of membrane transport proteins. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1289–1299. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiner H Y, Naider F, Becker J M. The PTR family: a new group of peptide transporters. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tame J R H, Murshudov G N, Dodson E J, Neil T K, Dodson G G, Higgins C F, Wilkinson A J. The structural basis of sequence-independent peptide binding by Opp protein. Science. 1994;264:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.8202710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terada T, Saito H, Mukai M, Inui K I. Recognition of β-lactam antibiotics by rat peptide transporters, PEPT1 and PEPT2, in LLC-PK1 cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F706–F711. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.5.F706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]