Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a condition of brain dysfunction1,2 that is misunderstood and under-recognised in Britain. Research shows that it is a genetic, inherited condition that can be effectively managed. Studies of twins suggest an exceptionally high concordance,3 and genetic studies show a likely polygenetic basis for inheritance.4 Evidence of brain dysfunction has been found in cerebral imaging studies, including functional magnetic resonance imaging, quantitative electroencephalography, and positron emission tomography.5 If untreated the disorder may interfere with educational and social development and predispose to psychiatric and other difficulties. There is much myth and misinformation, fuelled by personal bias and the media, surrounding the existence and treatment of the condition, which has led to an assumption that it is overdiagnosed and overtreated in Britain.

Psychosocial approaches encourage the belief that poor parental discipline causes most children’s behaviour problems. Such approaches generally ignore a biological basis to difficulties in self control, concentration, and hyperactivity. Widespread ignorance exists about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and the need for drugs as a component of treatment. Trite and simplistic explanations for the symptoms of the disorder are perpetuated which encourage the view that merely naughty children are being diagnosed to absolve parental responsibility. Considerable care and expertise is essential in assessing children’s emotional and behavioural problems to ensure accurate diagnosis. There are three main myths that need to be overcome: what constitutes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, that the disorder is the same as hyperkinesis, and that the drugs used for treatment have serious side effects.

Confusion over nature of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a common but complex medical condition characterised by excessive inattentiveness, impulsiveness, or hyperactivity that significantly interferes with everyday life. The continuing presence of symptoms is essential for diagnosis. The condition manifests in many ways. For example, some children may be only inattentive; others may be persistently hyperactive; for some, hyperactivity may lessen with time. The wide range of possible presentations can be confusing. There are also many complications that may mask or overshadow the underlying core symptoms and worsen with time (box).

Common coexisting conditions and complications of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

• Oppositional defiant disorder

• Conduct disorder

• Depression

• Anxiety and obsessions

• Specific learning difficulties

• Speech and language disorder

• Low self esteem

• Social skills difficulties

• Relationship problems

• Substance abuse

• Auditory processing difficulties

• Dyspraxia

• Asperger’s syndrome

The core symptoms needed to be assessed both at home and school as does the functional impact of the complicating features. Children who are untreated and have conduct disorder are at much higher risk of later criminal activity.

Hyperkinesis versus attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

British professionals have traditionally used the more restrictive World Health Organisation and ICD 10 term “hyperkinesis,” which means severe, persistent hyperactivity. Many people wrongly believe that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is the less severe form of hyperkinesis. In fact, hyperactivity is just one possible feature of the disorder.

The DSM IV criteria of the American Psychiatric Association provide a broader, more realistic concept and include all possible manifestations of the disorder. Reliance on hyperkinesis as a benchmark of diagnosis excludes many children displaying other manifestations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and these children are often denied appropriate management of their problems. Rutter et al noted 30 years ago that hyperactivity lessened with time but that it was often replaced by other problems, especially antisocial and learning difficulties.6

Myths about medical management

Ignorance of the role of drugs such as methylphenidate (Ritalin) as an essential component of multidisciplinary management of attention deficit disorder has encouraged further controversy. Drugs are highly effective in improving concentration and impulsiveness and lessening hyperactivity. Often an associated improvement occurs in many of the other difficulties, although second drugs may be needed. Methylphenidate has a dopaminergic effect; each dose lasts about four hours. Experienced adjustment of dose and timing is essential for optimum treatment. The media have greatly exaggerated the side effects. The incidence of side effects is low. They are transient and dose related. Research indicates that concern about long term tolerance, addiction, or growth suppression is unfounded.

Children do not usually grow out of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by puberty and treatment is indicated for as long as benefit is obtained. About 60% of sufferers still have the condition in adulthood.

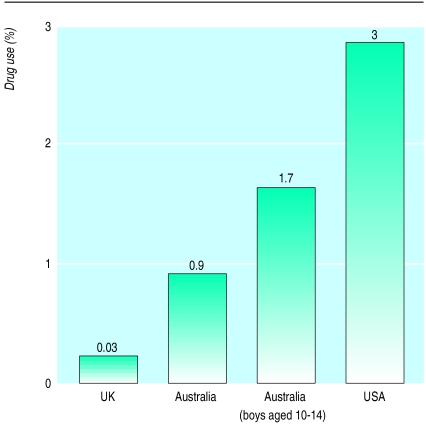

Substantial national differences exist in rates of treatment in Britain, Australia,7 and North America8 (figure). British government data show that in 1995 up to 6000 children were being treated with psychostimulants.9 This equates to 0.03% of UK schoolchildren. As the incidence of severe hyperactivity in Britain is 0.5-1%,10 this demonstrates considerable undertreatment of the disorder.

Overseas experience shows that both paediatricians and child psychiatrists have a role in effective multidisicplinary management of attention deficit disorder. Cooperation with general practitioners and educational and counselling services is esssential for effective service provision.

Previous reports on provision and purchasing of community paediatric and child and adolescent mental health services have failed adequately to recognise the importance of attention deficit disorder in such services.11 Professionals must understand the reality of the disorder and its importance as a public health issue for children and adults. Drugs have an essential role when combined with educational, psychological, and other strategies as appropriate.

Figure.

Proportion of children receiving psychostimulants in United Kingdom, Australia, and United States

References

- 1.Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder—a handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantwell DP. Attention deficit disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:978–987. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy F, Hay DA, McStephen M, Wood C, Wildman I. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a category or a continuum? Genetic analysis of a large scale twin study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:737–744. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smalley SL. Genetic influences in childhood on psychiatric disorders. Autism and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1276–1282. doi: 10.1086/515485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kewley GD. ADHD—a guide for parents and professionals. London: LAC Press (in press).

- 6.Rutter M, Graham P, Yule W. A neuropsychiatric study in childhood. London: Spastics International Medical Publications, Heinemann; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Report of working party on ADHD. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents and adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(suppl):1311. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Treating problem behaviour in children. POST Tech Rep. 1997;92:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor E, Hemsley R. Treating hyperkinetic disorders in childhood. BMJ. 1995;310:1617–1618. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6995.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R, Richardson G. Child and adolescent mental health services. Together we stand—the commissioning, role and management of child and adolescent mental health services. London: HMSO; 1995. [Google Scholar]