Abstract

Youth in foster care with maltreatment experiences often demonstrate higher rates of mental and behavioral health problems compared to youth in the general population as well as maltreated youth who remain at home. Previous research has demonstrated that dimensions of maltreatment (type, frequency, and severity) and placement instability are two prominent factors that account for high rates of psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, and disruptive behavior disorders). The present study sought to clarify the relation between maltreatment and mental health among youth in foster care by studying both the isolated dimensions of maltreatment and cumulative maltreatment, and to determine whether the effects of maltreatment on mental health operated indirectly through placement instability. Information on youth in foster care’s (N = 496, Mage = 13.14) mental and behavioral health, maltreatment history, and placement changes were obtained from state records and primary caregivers. Using a SEM framework, the results suggest that maltreatment and placement instability each independently relate to mental and behavioral health problems. Further, none of the maltreatment types predicted greater placement instability in the current models. These findings suggest that placement stability is critical for mental health for youth in foster care, regardless of the type, severity, or frequency of their maltreatment experiences. Results also indicated that, although cumulative maltreatment predicted both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, maltreatment frequency and severity had direct relations to externalizing symptoms only. These findings underscore the utility of comprehensive maltreatment assessment, encouraging researchers and clinicians to assess and carefully consider the relation between maltreatment dimensions and outcomes.

Keywords: Maltreatment, Foster care, Youth, Mental health, Placement instability

1. Introduction

Fordecades, child maltreatment (e.g., neglect, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) has been considered a major risk factor for multiple forms of psychopathology. A wealth of studies suggest that child maltreatment is associated with increased risk for the onset of the most commonly occurring forms of internalizing (e.g., anxiety and mood disorders) and externalizing (e.g., substance use and disruptive behavior disorders) psychopathology in youth (Carliner, Gary, McLaughlin, & Keyes, 2017; McLaughlin et al., 2012; Oswald, Heil, & Goldbeck, 2010 for review). Youth in foster care, a population exposed to maltreatment that is sufficiently severe to warrant removal from the home, may be even more likely than other youth exposed to maltreatment to suffer from mental and behavioral health problems (Hambrick, Oppenheim-Weller, N’zi, & Taussig, 2016). Prior research suggests that maltreated youth who are placed in foster care tend to have higher rates of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, compared to maltreated youth who remain in their homes of origin (Ryan & Testa, 2005), and that symptoms increase over time for youth in foster care whereas they do not for youth residing in their homes of origin (Lawrence, Carlson, & Egeland, 2006). A systematic review of the relation between maltreatment and mental health illustrated the high prevalence of clinically significant mental and behavioral health problems among youth in foster care, finding that 36–61% of youth in foster care were in the clinical range for behavior problems, and 32% to 44% met criteria for psychiatric disorders (Oswald et al., 2010).

Although it is clear from the literature that youth in foster care are at-risk for mental health problems compared to maltreated youth who remain in their homes of origin, understanding how the combination of maltreatment and foster care placement affects mental health is more complex. First, the aspects of maltreatment that contribute to internalizing and externalizing symptoms must be examined. In the aforementioned systematic review, results indicated that certain characteristics of maltreatment – namely type, severity, and frequency – uniquely contribute to mental health in foster care populations (Oswald et al., 2010). For example, the impact of maltreatment type can be seen in results showing that foster care youth who have been physically abused tend to display more conduct problems, hyperactivity, and overall behavior problems compared to children who have been neglected (Marquis, Leschied, Chiodo, & O’Neill, 2008). Further, in a sample of youth in residential care, those presenting with clinical levels of anxiety had more severe emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, but not physical abuse, as compared to youth with subclinical levels of anxiety (Collin-Vézina, Coleman, Milne, Sell, & Daigneault, 2011).

Although not as widely studied as maltreatment type, multiple studies have demonstrated the importance of taking into account severity and frequency when examining outcomes associated with maltreatment. Severity of maltreatment is often conceptualized as the amount of physical or psychological harm, or possible harm, of the maltreatment experience. The current evidence tends to suggest a positive association between maltreatment severity and mental health problems in foster care youth, such that greater severity is linked with more mental and behavioral concerns (Jackson, Gabrielli, Fleming, Tunno, & Makanui, 2014; Litrownik et al., 2005). For example, McCrae, Chapman, and Christ (2006) examined what factors may explain why some youth with maltreatment demonstrate mental and behavioral concerns. Using mixture modeling, the authors found that abuse severity may be a more important distinguishing or explanatory factor of mental and behavioral concerns, as opposed to chronicity of abuse. Moreover, the relation between maltreatment severity and mental health problems appears to be fairly robust, as Litrownik et al. (2005) found that maltreatment severity, operationalized in four different ways (i.e., overall maximum severity, maximum severity for each type, overall mean severity, and mean severity across two developmental periods), was associated with behavior problems and psychological functioning in children.

In many studies, frequency of maltreatment is defined as the number of times a child experiences maltreatment. As with severity, frequency of maltreatment experiences tends to be positively associated with poor mental health outcomes (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005; Van Wert, Mishna, Trocme, & Fallon, 2017). For example, in a large study examining adolescents in urban schools, maltreatment frequency was positively associated with depression and delinquent behavior (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Brien, 2007). Similarly, in a sample of youth in foster care, results showed that the more often youth were exposed (i.e., greater number of maltreatment and other traumatic events), the greater the odds were for scoring in the clinical range on measures of anxiety, depression, and overall internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Raviv, Taussig, Culhane, & Garrido, 2010). Yampolskaya, Armstrong, and McNeish (2011) also found that maltreatment frequency or chronicity, as opposed to severity, was associated with a higher risk of involvement in the juvenile justice system for youth in out of home care. Thus, more frequent maltreatment, among other risk factors, resulted in significantly more mental health problems.

While there is initial evidence to support the association between type, frequency, and severity of maltreatment to mental health, there are several limitations with regard to the previous methods used to study these relations. First, previous research has tended to exclusively focus on one dimension of maltreatment in each study or the dimensions for each type in isolation. Maltreatment is multidimensional and complex construct comprised of various characteristics (Manly, 2005), and not accounting for the various dimensions simultaneously could lead to inaccurate conclusions (Gabrielli, Jackson, Tunno, & Hambrick, 2017). Jackson et al. (2014) tested the possible unique roles of frequency and severity to understand each variable’s role in predicting behavioral functioning in foster youth. To measure severity of maltreatment exposure, each event endorsed by the youth was a priori organized into mild, moderate, and severe categories based on the potential for each event to cause lasting harm or disability, and then weighted in the summing of each event based on the category. Frequency of maltreatment was the sum of the frequency scores for the abuse items endorsed by each child, ranging from never to always. Within an SEM path model, frequency and severity was regressed on externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behavior. Results showed that more severe maltreatment was related to greater externalizing behavior, and that less severe maltreatment was related to greater adaptive behavior. Maltreatment frequency was not predictive of youths’ behavioral functioning. While this is a helpful start, the present study sought to add to this work as very little research to date has examined the unique aspects of each maltreatment dimension simultaneously in relation to mental health outcomes for youth in foster care.

Second, it may also be that what matters is the accumulation or total of youths’ maltreatment experiences. Polyvictimization, or exposure to multiple types and multiple events of maltreatment, tends to be the norm in youth samples (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). Moreover, there is often considerable overlap between experiences and dimensions of maltreatment (Gabrielli et al., 2017; Manly, 2005). Rather than examine each dimension independently, what may be needed to better understand the link between maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing concerns is to examine this relation by taking into account youths’ entire maltreatment experiences using techniques that account for the severity and frequency of each type, such as creating a measurement model for maltreatment. This type of analysis may provide a more accurate picture of the youths’ experiences by taking into account the shared components of youths’ complete maltreatment history. Although the concept of complex trauma, or experiencing more than one interpersonal trauma early in life, has recently opened the door for many researchers to examine type, severity, and frequency of maltreatment simultaneously, more research is needed, particularly among youth in foster care and in association with mental health outcomes (Cook et al., 2017; Greeson et al., 2011; Wamser-Nanney, 2016).

Overall, the current study sought to improve understanding of the relation between maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing concerns in youth in foster care. The techniques used to operationalize maltreatment vary greatly across studies, where in some cases researchers will define maltreatment as a count of events, which event was most severe, or just a yes/no category. While there is literature on each dimension of maltreatment, rarely do studies examine more than one dimension or compare findings across dimensions within the same study. In the current study, the association between maltreatment and mental health was examined using a more comprehensive approach that accounted for the dimensions of each type simultaneously. Second, the current study sought to expand on this research by examining the totality of foster care youths’ maltreatment exposure through the use of a maltreatment measurement model in relation to mental health. In both approaches, the role of placement instability was also examined. By comparing these methods within the same study, it may be possible to determine if differences in findings are associated with the methods used to measure maltreatment.

1.1. Role of placement instability

In addition to certain characteristics of maltreatment experiences, placement instability may also play an important role in the maltreatment and mental health relation for youth placed in foster care. That is, for youth in foster care, another contributor to mental health problems could be placement instability. Placement instability is defined as household and/or institutional moves or placement changes that do not result in a child’s permanent placement (Fisher, Mannering, Van Scoyoc, & Graham, 2013). Youth change placements for multiple reasons including factors associated with the child (e.g., behavioral problems), the foster care family (e.g., life events that affect a foster family’s ability to care for the child), and both the child and family (e.g., mismatching of child and family characteristics; James, 2004). Youth medical complexity has also been shown to contribute to placement instability (Seltzer, Johnson, & Minkovitz, 2017). Placement instability is common for youth in foster care. For example, some estimates suggest that approximately one third of youth in foster care experience three or more placement changes during their time in care (Rubin et al., 2004), whereas others report that approximately one-third of youth in foster care experience eight or more changes (Pecora, Kessler, & Williams, 2005).

The experience of placement instability in foster care may partially account for the relation between maltreatment characteristics and mental health problems among youth in foster care. First, placement instability has been found to be associated with negative mental and behavioral outcomes, in both the short and long term, independent of maltreatment characteristics (Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000; Proctor, Skriner, Roesch, & Litrownik, 2010). Newton et al. (2000) found that placement instability was related to depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as aggression. Further, they found that among children who had more than four placement moves, number of moves explained 9.7% of the variance in internalizing symptoms and 6.7% of the variance in externalizing behaviors (Newton et al., 2000). Placement instability appears to have enduring, deleterious effects, as it has been related to criminality and substance use in adulthood (DeGue & Widom, 2009; Stott, 2012). Further evidence for the association between placement instability and well-being comes from research showing that children with high placement stability tend to demonstrate non-clinical behavioral adjustment while in out-of-home care (Proctor et al., 2010).

Second, empirical evidence shows that certain characteristics of child maltreatment are linked to placement instability (Steen & Harlow, 2012). For example, type of maltreatment may influence which youth experience more placement changes. James (2004) found that exposure to emotional abuse, but not sexual or physical abuse or neglect, predicted placement changes that were related to youths’ behavior problems. Moreover, James, Landsverk, and Slymen (2004) examined factors that might account for differences in placement patterns for youth in foster care. The authors found that, compared to childhood neglect and other forms of abuse, sexual abuse was more strongly predictive of an unstable pattern of care (i.e., multiple placements with no placements lasting longer than nine months). This is also consistent with results from a study by Holland and Gorey (2004), who reported that the odds of experiencing two or more placements were greater for sexually abused youth, as compared to neglected and physically abused youth. However, another study reported that compared to abused youth, neglected youth were more at risk of placement instability (e.g., Connell et al., 2006).

Overall, there appears to be growing evidence for associations between maltreatment types and placement instability. To date, fewer studies have examined the relation between placement instability and other characteristics of maltreatment such as severity and frequency. Although evidence supports a link between maltreatment characteristics and placement instability, and between placement instability and mental health outcomes, the indirect relation from maltreatment characteristics to mental health outcomes via placement instability has rarely been tested. Villodas, Litrownik, Newton, and Davis (2015) identified different placement trajectories in a sample of foster children using latent class analyses, and found that children with the greatest placement instability had disproportionately high rates of removal for sexual abuse. This high level of placement instability was then associated with behavior problems. This study provides important initial evidence linking aspects of maltreatment, placement, and mental health. Further, in another study, Villodas et al. (2016) found that adverse childhood experiences mediated the relation between placement instability and elevated mental health problems during late childhood, again providing substantial evidence for these relations.

Placement changes as a result of maltreatment can occur through many different pathways. For example, a child’s past maltreatment experiences can negatively impact the relationship quality between a child and his or her foster caregiver, thereby possibly leading to later placement disruptions (Gilbert et al., 2009; James, 2004; Lewis, Granic, & Lamm, 2006). Given the repeated disruption to their social and emotional support networks, youth experiencing placement instability might feel abandoned and rejected, increasing their risk of mental and behavioral difficulties. Should placement instability emerge as a link in the chain connecting maltreatment characteristics to mental health outcomes, this may present promising opportunities to improve adjustment of maltreated children by addressing child welfare policy and practice related to placement stability goals for youth in foster care.

Despite substantial evidence that maltreatment (and its various dimensions) and placement instability are each independently linked with poor mental health outcomes among youth in foster care, it remains unclear whether placement instability may account for all or part of the association between maltreatment dimensions and mental health in foster care youth. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to determine the indirect effects of placement instability on the associations between maltreatment and mental health, while also determining how differences among the various dimensions of maltreatment (frequency, severity, and type) relate to mental health among youth in foster care. It was hypothesized that the associations between severity, frequency, and type of maltreatment experiences would be indirectly associated with mental health outcomes via number of placement moves. Moreover, the current study also tested the above relations with a maltreatment measurement model, which takes into account youths’ cumulative maltreatment history to determine if this approach (compared to the dimensional approach to operationalizing maltreatment) better explained the association between placement changes and mental health.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample included 496 youth in foster care and their primary caregiver recruited from a Midwest metropolitan area. A total of 518 participants took part in the project at time point one, but 22 participants were not included in the current study because of no case file information. Data for the current study was obtained through caregiver report and the case file reports of the youth in the study. Eligibility for the study included youth’s IQ of 70 or above, youth age of 8 years or older, and youth living in their current placement for a minimum of 30 days (the minimum amount of time required to complete the BASC-2). Participating youths’ ages ranged from 8 to 21 (M = 13.14, SD = 3.08), with an even gender split between male (51.5%) and female (48.5%). Youth were primarily identified by caregivers as African American (49.2%), followed by White or Caucasian (34.1%), Multiracial (9.7%), Hispanic or Latino (3.6%), other (1.2%), Asian (.4%), and American Indian (.4%). Caregivers in the study were comprised of 50% foster parents, 37% residential facility staff, and 13% biological relatives such as grandparents. 2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Maltreatment

The Division of Social Services (DSS) provided case files for participating youth and each file was coded using the Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS; English & the LONGSCAN Investigators, 1997). All maltreatment incidents were coded by trained coders from the reporter narratives in the case file, and codes included all reports, including those not investigated and those classified as substantiated by DSS.

Using the MMCS, the type of maltreatment (e.g., physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect) as well as the number of maltreatment incidents were coded. The severity of maltreatment incidents was also coded based on the MMCS, which specifies severity by the quality and time period of the incident. For example, a mild severity rating (MMCS severity coding of 1) for an incident of neglect would be a general lack of supervision, whereas a more severe rating (MMCS severity code of 4) for an incident of neglect might include a child being left alone overnight (English & the LONGSCAN Investigators, 1997). Those coding the case files received training and obtained a kappa of reliability of .80 to assure interrater reliability and consistency with the MMCS coding. For more information on the coding procedures and training, see Huffhines et al. (2016).

2.2.2. Mental health

Caregiver report of the Behavioral Assessment System for Children-2, Parent Report Form (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) was used as the measurement of mental health symptoms. The adolescent version (150 items) was given to caregivers reporting on adolescents (ages 12 and older) and the child version (160 items) was given to caregivers reporting on children (ages 8–12). The BASC-2 assesses various mental health concerns, on a scale from “Never” to “Always.” Two BASC-2 composite scales, Internalizing and Externalizing, were used in the current study. The Internalizing Problems composite consists of the anxiety, depression, and somatization subscales. The Externalizing composite consists of the hyperactivity, aggression, and conduct problems subscales. The BASC-2 has been used frequently in various research studies to examine mental health symptoms of children and adolescents, with excellent internal consistency and construct validity, with composite alphas on parent reports ranging from .89 to .95 (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). For the current study, the Internalizing composite for the child version (N = 191) had an alpha of .94 and the Externalizing composite had an alpha of .96. The alpha for the Internalizing composite of the adolescent version (N = 305) was .93 and .96 for the Externalizing composite.

2.2.3. Placement instability

Placement instability was determined using records from DSS, which provided information on the total number of placement moves across the youths’ lifetime while in foster care. This included all types of changes, such as changes to and from a residential facility, to and from foster care families, or emergency placements.

2.3. Procedures

The current study was part of a larger federally funded, longitudinal research project, Studying Pathways to Adjustment and Resilience in Kids (SPARK). The SPARK project investigated mental health outcomes among foster youth who have experienced maltreatment. Data was collected from participants at three time points, but only data from the first time point was included in the current study. This project was approved by the researcher’s university institutional review board (IRB) and the state social service agency. All participants in the current study were recruited from a large Midwestern county. DSS provided the SPARK research team with a list and contact information for all eligible participants in the county. This included all youth above age eight in foster care for the county at the time of data collection. In total, this included access to contact information for approximately 2700 youth. Participants were recruited using multiple methods, including directly mailing and calling eligible foster families, placing advertisements in newsletters and list-serves, holding recruitment community events, and referrals. This type of recruitment method allowed for a representative sample of the population (demographics of the sample matched the larger population of youth in foster in the county).

All formal consent for participating foster youth was provided by this social service agency. In addition, youth also completed an assent form prior to participation. Access to youths’ case file information was granted by the state social service agency. Youths’ caregivers provide their own consent. Participating youth and caregivers were provided with an explanation of the study and the mandated reporting of researchers in the event of suicidality, homicidality, or child maltreatment before providing their consent for participation.

Caregiver participants completed the study questionnaires through an audio-computer assisted self-interview (ACASI). The ACASI system presented questions to caregivers visually on a computer screen, as well as read questions aloud to participants via headphones. This type of data collection method aides in assuring that reading challenges did not impact caregivers’ ability to participate, and also helped ensure privacy and confidentially. Other measures not related to the current study were also completed at this time. Following completion of study measures, youth and their caregivers completed a comprehensive debriefing process with a graduatelevel, clinical child psychology student. This included steps such as follow up if there was any indication of current maltreatment or suicidality, distribution of mental health resources, and a follow up call within 48 h. For more information on the procedures of the larger study, including the recruitment and debriefing process, see Jackson, Gabrielli, Tunno, and Hambrick (2012).

2.4. Data analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the hypothesis that placement instability would indirectly affect the association between maltreatment and mental health outcomes. Since data was missing at random, missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML). FIML uses a likelihood function to calculate unbiased parameter and standard error estimates based on the association between non-missing variables. Moreover, maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to calculate model estimates, which takes into account multivariate non-normality. Total missing data was 1.7%.

Analyses were carried out in two parts. For the first part, the different dimensions (frequency and severity) of maltreatment were examined in separate path models with externalizing and internalizing symptoms as the outcome variables. One model included the frequency scores (maltreatment frequency path model) and one model included the severity scores (maltreatment severity path model) for each type of maltreatment (physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and neglect). Placement instability was included as an indirect effect between each maltreatment dimension and the outcome variables. For each model, age was included in the model as a covariate.

In the second part, a measurement model for maltreatment was developed using a previously tested and validated measurement model (For more information, see Gabrielli et al., 2017). The model included the frequency and severity score for each maltreatment type. The proposed model included correlations between the severity and frequency score for each maltreatment type to account for the shared variance for each maltreatment type. A fixed factor scaling method was used by setting the variance of the maltreatment latent variable to 1.0, which created standardized parameter estimates. Following estimation of the proposed model, correlations between the maltreatment variables and modification indices were examined for potential model re-specification. After construction of the maltreatment model with good fit, the maltreatment latent variable was included in a path model to test the indirect effect of placement instability in the association between maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Age was included in the model as a covariate. Prior to analyses, all variables were mean centered to aid interpretability of the coefficients (Kline, 2015).

Bootstrap bias corrected confidence intervals were used to estimate the direct and indirect pathway coefficients to test the association between maltreatment and placement changes (predictors), and symptoms (outcomes) (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). This type of estimation increases statistical power and produces lower Type-I error rates. Multiple fit indices (and their respective cutoffs) were used to evaluate model fit in both the first and second part of data analysis. This included the rootmean-square residual error of approximation (RMSEA; < .05), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; < .08), the comparative fit index (CFI; > .95), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; > .95) (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

3. Results

The means, standard deviations, and ranges for all study variables are presented in Table 1. The most common type of maltreatment experience reported was neglect, followed by physical abuse, emotional abuse, and then sexual abuse. Moreover, the current sample experienced approximately nine placement changes on average, which is in line with previous reports on how often youth transition in care (e.g., Casey Family Programs, 2005). On average, youth demonstrated externalizing and internalizing symptoms in the borderline range, based on the standardization sample for the BASC-2 (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges for Study Participants.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 13.14 (3.08) | 8–21 |

| Placement Changes | 9.20 (6.57) | 1–46 |

| Externalizing Symptoms | 69.04 (14.53) | 36–112 |

| Internalizing Symptoms | 62.04 (12.62) | 34–107 |

| Physical Abuse Frequency | 2.19 (3.45) | 0–30 |

| Physical Abuse Severity | .83 (.92) | 0–4 |

| Sexual Abuse Frequency | .76 (1.72) | 0–14 |

| Sexual Abuse Severity | .93 (1.62) | 0–6 |

| Emotional Abuse Frequency | .82 (1.36) | 0–8 |

| Emotional Abuse Severity | 1.02 (1.42) | 0–5 |

| Neglect Frequency | 2.66 (3.63) | 0–25 |

| Neglect Severity | 1.30 (1.32) | 0–5 |

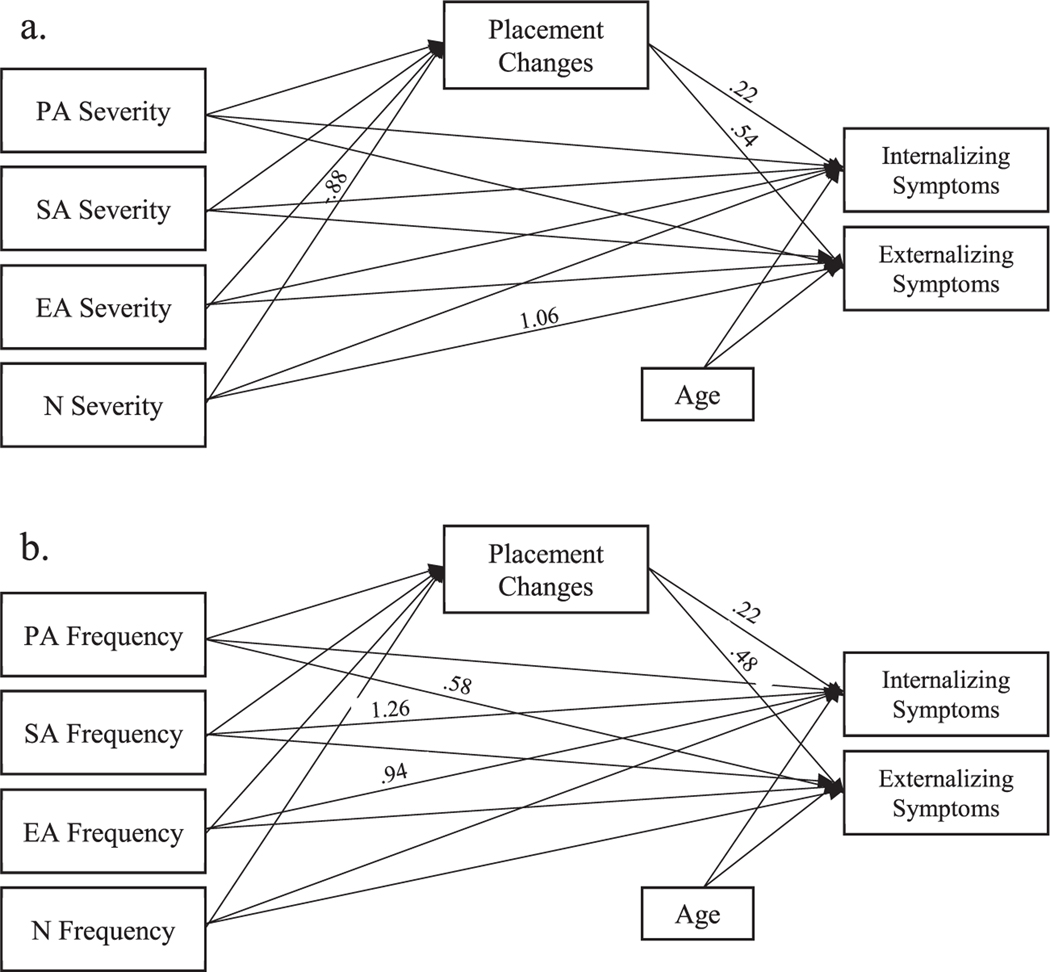

The parameter estimates and fit indices for both the maltreatment frequency and severity path models are presented in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 1. The maltreatment severity path model demonstrated adequate model fit (χ2 (4, n=496) = 6.92, p = .01, RMSEA(.00-.09) = .04, SRMR = .02, CFI = .99, TLI = .92) and the maltreatment frequency path model demonstrated adequate fit (χ2 (4, n=496) = 10.71, p = .03, RMSEA (.02-.10) = .06, SRMR = .02, CFI = .97, TLI = .84). For direct effects in the path model including maltreatment severity, neglect severity was significantly positively associated with externalizing symptoms (β = 1.06, p = .04) and neglect severity was significantly negatively associated with placement changes (β = −.88, p < .01). No other maltreatment severity predictors were significant. Placement changes was significantly positively associated with both internalizing (β = .54, p < .01) and externalizing symptoms (β = .22, p = .05). Moreover, examination of the indirect effects showed that the effect of neglect severity was related to internalizing symptoms through number of placement changes (β = −.47, p = .01). That is, more severe neglect was associated with fewer reported internalizing symptoms after accounting for the influence of placement changes.

Table 2.

Path Analysis Estimates Examining Each Dimension of Child Maltreatment Separately.

| Variable | Maltreatment Severity |

Maltreatment Frequency |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | R 2 | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | R 2 | |

| Externalizing Symptoms | .07 | .07 | ||||

| Physical Abuse | .85 | .19 | .58** | −.001 | ||

| Sexual Abuse | −.61 | .16 | .19 | .02 | ||

| Emotional Abuse | .4 | .01 | .33 | .06 | ||

| Neglect | 1.06** | −.47** | −.22 | −.07 | ||

| Placement Changes | .54** | .48** | ||||

| Age | −.03 | −.12 | ||||

| Internalizing Symptoms | .02 | .06 | ||||

| Physical Abuse | .56 | .08 | .11 | 0 | ||

| Sexual Abuse | .27 | .07 | 1.26** | .01 | ||

| Emotional Abuse | .01 | .01 | .94** | .03 | ||

| Neglect | .1 | −.2* | −.01 | −.03 | ||

| Placement Changes | .22** | .22** | ||||

| Age | .18 | .13 | ||||

| Placement Changes | .03 | .01 | ||||

| Physical Abuse | .35 | −.002 | ||||

| Sexual Abuse | .3 | .03 | ||||

| Emotional Abuse | .03 | .11 | ||||

| Neglect | −.88** | −.14 | ||||

Note.

p ≤.10.

p < .05.

Fig. 1.

a and b. Mediation models of the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and (a) maltreatment severity measurements and (b) maltreatment frequency measurements. The endogenous and exogenous variables were permitted to correlate with among each other, although those correlations are not depicted in the figure to improve clarity. PA= Physical Abuse, SA =Sexual Abuse, EA =Emotional Abuse, N =Neglect. Significant pathway estimates (p < .05) shown with bold line. Marginally significant pathway estimates (.05 < p < .10) shown with dashed line.

For the model including maltreatment frequency, results showed a significant direct effect for physical abuse frequency on externalizing symptoms (β = .29, p = .03). Moreover, a significant direct association was observed for sexual abuse frequency (β = 1.26, p < .01), as well as a marginally significant association for emotional abuse frequency (β = .29, p = .06) with externalizing symptoms. Placement changes was significantly positively associated with both internalizing (β = .22, p = .05) and externalizing symptoms (β = .48, p < .01). There were no significant indirect effects with placement changes for any maltreatment frequency type for either internalizing or externalizing problems (all p’s > .05). In both dimensional approach models, the findings show that the maltreatment characteristics and placement changes are each independently associated with externalizing and internalizing symptoms.

3.1. Maltreatment measurement model

Next, the maltreatment measurement model was used to test the relations among maltreatment, placement instability, and mental health. Whereas the previous two models examined maltreatment severity and frequency as independent predictors, the maltreatment measurement model utilized both the severity and frequency of each type of maltreatment experience in the same model to create a latent variable of maltreatment. The proposed model demonstrated adequate fit (χ2 (16, n=496) = 58.00, p < .001, RMSEA (.05-.09) = .07, SRMR = .04, CFI = .96, TLI = .93). Given the model only demonstrated adequate fit, further examination of correlations between the maltreatment variables and modification indices were examined, and the correlation between physical abuse frequency and emotional abuse frequency was freed, which is also in line with previous research finding that physical and emotional abuse are highly correlated (e.g., Bolger & Patterson, 2001). Following this change, the maltreatment model showed excellent fit (χ2 (15, n=496) = 19.64, p = .19, RMSEA (.00-.05) = .03, SRMR = .02, CFI = .99, TLI = .99). This model was then used in the full structural model.

The factor loadings and the parameter estimates are presented in Table 3 and shown in Fig. 2. Overall, the full SEM model demonstrated adequate fit (χ2 (45, n=496) = 107.17, p < .001, RMSEA (.04-.07) = .05, SRMR = .05, CFI = .95, TLI = .93). All factor loadings were significant (p < .01), and were in the acceptable range. There were no high loadings, which is common in large measurement models, and all variables were included in the model as suggested by previous research using a similar model and theoretical consideration (Gabrielli et al., 2017). Results from the path analysis showed significant positive associations for maltreatment (β = 1.87, p = .05) and placement changes (β = .53, p < .01) on externalizing symptoms. Maltreatment (β = 1.52, p = .04) and placement changes (β = .26, p = .02) were also significantly positively associated with internalizing symptoms. No significant indirect effects were observed (all p’s > .05). In summary, the model shows that maltreatment and placement changes, each independently contributed to more externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and that placement change did not account for indirect effects between maltreatment and outcomes.

Table 3.

Maltreatment Measurement Model Factor Loadings and Path Estimates.

| Measurement Model | Standardized Loading | R 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Physical Abuse Frequency | .37** | .14 | ||

| Physical Abuse Severity | .47** | .23 | ||

| Sexual Abuse Frequency | .26** | .07 | ||

| Sexual Abuse Severity | .31** | .1 | ||

| Emotional Abuse Frequency | .59** | .36 | ||

| Emotional Abuse Severity | .55** | .3 | ||

| Neglect Frequency | .43** | .18 | ||

| Neglect Severity | .56** | .31 | ||

|

| ||||

| Structural Model | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | R 2 | |

|

| ||||

| Externalizing Symptoms on | .07 | |||

| Maltreatment | 1.87** | −.30 | ||

| Placement Changes | .53** | |||

| Age | .02 | |||

| Internalizing Symptoms on | .03 | |||

| Maltreatment | 1.52** | −.15 | ||

| Placement Changes | .26** | |||

| Age | .22 | |||

| Placement Changes on | .01 | |||

| Maltreatment | −.57 | |||

Note.

p ≤.10.

p < .05.

Fig. 2.

Maltreatment Measurement Model with Path Estimates. PA= Physical Abuse, SA =Sexual Abuse, EA =Emotional Abuse. Significant pathway estimates (p < .05) shown with bold line.

4. Discussion

Past research has established that maltreatment and placement instability are related to maladjustment among youth in foster care (Steen & Harlow, 2012). Youth in foster care who experience maltreatment and changes in placement are more likely to demonstrate both internalizing and externalizing concerns (Newton et al., 2000; Ryan & Testa, 2005). To better illuminate the possible ways exposure to maltreatment, as well as changes in placement, may explain the presentation of significant pathology (e.g., internalizing, externalizing) in youth in foster care, the current study sought to build on past research by using a comprehensive method to conceptualize maltreatment. This was achieved by (a) using an approach that specifically examines the frequency and severity of each type of maltreatment simultaneously, and (b) creating a maltreatment measurement model that accounts for the whole of youths’ maltreatment experiences when examining the relation between maltreatment, placement instability, and mental health.

The results of the current study confirmed previous findings that placement instability is related to mental and behavioral health problems among youth in foster care (Newton et al., 2000; Proctor et al., 2010). In this sample, placement instability had significant, positive associations with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. These relations were consistently observed in three different models with maltreatment frequency, severity, and an overall measurement, indicating the robustness of the associations between placement instability and mental and behavioral health problems, no matter which method was used to conceptualize maltreatment. Although it has been suggested that mental and behavioral health problems can contribute to placement instability among foster youth (Palmer, 1996), these findings provide support that the reverse is true as well. In this study, the total number of placement changes was captured prior to gathering reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms from youths’ most recent foster caregiver, lending support for the interpretation that placement instability is associated with mental health problems. Further, a previous study disentangled the relation between placement instability and mental and behavioral health problems, finding that while externalizing problems can lead to placement changes for some children, others who enter care with average levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms are most likely to see a rise in those symptoms as a consequence of placement instability (Newton et al., 2000). These findings, in concert with previous research suggesting that mental and behavioral problems contribute to placement instability, suggest a possible bidirectional relationship between these variables.

In addition to confirming previous findings that placement instability is linked with mental and behavioral health problems, maltreatment was also implicated as a contributor to mental health problems among youth in foster care. This association has been thoroughly documented in the literature (Cicchetti & Toth, 2005). The present study contributes to the body of literature on this topic by examining the association of adjustment not only with maltreatment as unitary construct (i.e., examined by a yes/no construct), but also with the various dimensions of maltreatment, including type, frequency, and severity. When examined separately, it appears that the various dimensions of maltreatment relate differently to adjustment, with surprising results. For instance, neglect severity was positively associated with externalizing but not internalizing, whereas other studies have found the opposite relation (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002). In contrast, sexual abuse frequency was related to externalizing, but not internalizing symptoms, which is in line with previous findings linking sexual abuse frequency to certain types of externalizing behaviors such as delinquent behavior (Ruggiero, McLeer, & Dixon, 2000). In addition, the results of the current study reaffirm previous findings linking physical abuse with externalizing concerns (Carliner et al., 2017).

These results illustrate that maltreatment is a complex, multifaceted experience, and comparisons between the dimensional approach (i.e., examining frequency and severity for each type) and the measurement model approach suggest that the influence of maltreatment when examining its potential impact on foster youths’ well-being may best be understood by using a method that captures the entirety of maltreatment. The maltreatment model including type, frequency, and severity found the expected associations with adjustment, such that maltreatment was associated with both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. However, these findings might have been lost in research utilizing only the dimensional approach, as there were only two dimensions associated with externalizing symptoms in the dimension specific model. Use of the measurement model analysis method may provide a more accurate measure of maltreatment, as this approach is able to capture the overlap or shared variance between each dimension, which are often highly related to each other. Furthermore, the measurement model also helps to reduce measurement error, which is likely present when measuring maltreatment because maltreatment cannot be directly measured or measured using a single question or source of information. Instead, maltreatment is captured through tools and reports, such as the MMCS and case files, that assess the various components of maltreatment.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that both exposure to maltreatment and placement instability among foster care youth contribute to youths’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms. However, contrary to study hypotheses, the effect of maltreatment on mental health outcomes does not generally appear to operate via placement instability, but rather it seems that each has unique, direct effects on internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

The finding that placement instability did not account for the link between maltreatment and internalizing and externalizing symptoms among foster care youth might be driven by the insignificant association between maltreatment and placement instability in the current sample. This contradicts previous research, which has found significant positive associations between maltreatment and placement changes (Holland & Gorey, 2004; James, 2004). Maltreatment classification methods (e.g., maltreatment types in prior research versus maltreatment characteristics in the current study) might explain the inconsistency in findings. For example, Steen and Harlow (2012), who found that maltreatment predicted changes in placement, categorized youth into either a physical abuse or other maltreatment group and then compared differences, whereas the current study examined each type of maltreatment simultaneously in the same model, which was done for both the model with severity measurements and the model with frequency measurement. The examination of each separate maltreatment type within the same model for its respective dimension (either frequency or severity) allowed for the current study to take into account the overlap or polyvictimization between each maltreatment type, as youth tend to experience multiple types of victimization and there is often considerable overlap between each type (Gabrielli, Jackson, & Brown, 2016; Turner et al., 2010). In turn, when the overlap is taken into consideration, there is no particular type of maltreatment that contributes to placement instability. Even when using the measurement model method as well, which helps to capture the complexity of maltreatment in a single latent variable which accounts for the shared commonality (Gabrielli et al., 2017; Manly, 2005), there was still an insignificant association between maltreatment and placement stability.

The only significant association between maltreatment and placement instability was found for neglect severity, with more severe neglect predicting fewer number of placement changes during foster care. This finding is difficult to interpret given its contrast to some previous reports that neglect is a risk factor for placement instability, even more so than other forms of maltreatment (Connell et al., 2006). One possibility for the relation observed in this study is that severe neglect can lead to developmental delay, disability, or both (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002). Research shows that systems- and policy-level interventions can effectively promote placement stability for foster care youth with developmental disabilities (Connell et al., 2006; Redding, Fried, & Britner, 2000), and such interventions may be implemented in the organizations responsible for handling the placements of youth in the current study. It may be that the effects of severe neglect prompt systems- and policy-level decisions aimed to protect these particularly vulnerable youth from further harm due to placement instability. However, further research is needed to confirm this association and explore such systems-level factors.

4.1. Limitations

Despite the contributions of the current study, results should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the maltreatment values did not include any maltreatment the youth experienced after placement in foster care or while in a foster home. It is possible that youths continued to experience maltreatment in foster homes, residential centers, or during temporary return placements at their homes of origin. Further, the current study gathered information about maltreatment type, frequency, and severity by abstracting data from original case file records rather than self- or caregiver-report. Although this method conveys certain benefits such as avoiding recall errors (Hulme, 2004), it carries drawbacks as well. Namely, case file data may underestimate youths’ exposure to maltreatment relative to youths’ self-reports of some kinds of abuse because it often only represents what is reported and can be verified (Hussey, Chang, & Kotch, 2006). Similar to self-report data, case file data may also be dependent on the thoroughness and knowledge of the reporter. The discrepancy between case file and self-reported maltreatment varies across subtypes, with case files indicating somewhat more neglect and youths reporting substantially more emotional maltreatment (Cho & Jackson, 2016). Many researchers recommend using multiple sources of information to determine maltreatment exposure. Additionally, although a wide range of techniques were utilized in the recruitment process, it may be possible that the robustness of the findings are influenced by selection biases since approximately one-fifth of the total foster care population accessible to study personnel were recruited into the study. Lastly, the results from the maltreatment frequency and severity path models, that examined each maltreatment dimension individually, should be interpreted with some caution given that both models demonstrated adequate fit, as oppose to excellent fit.

4.2. Policy implications and future research

The current study has implications for child welfare policy and practice, and future research. Consistent with previous research (Newton et al., 2000; Ryan & Testa, 2005), the current study found that placement instability predicts internalizing and externalizing symptoms during placement in foster care. However, results did not support the hypothesized indirect effect of maltreatment on mental health outcomes through placement instability, which suggests that efforts to promote placement stability may not need to consider the nature of the child’s history of maltreatment (e.g., type, frequency, or severity). When placement changes are necessary, policy should reflect attention to the potential negative consequences that might arise as a result of placement instability. Specifically, child welfare agencies should consider policies requiring caseworkers to administer evidence-based broadband youth mental health measures to foster parents after youths enter new placements, and when measures indicate clinically significant behavior problems, to promptly provide foster parents with resources to address youths’ needs. Moreover, given that the association between placement instability and poor behavioral and emotional health appears to be fairly robust, child welfare organizations may consider providing services that help prepare youth and foster parents prior to placement changes. Although not directly tested in the present study, by giving youth the supports they need to cope with the uncertainty and stress of moving from home to home, and preparing foster parents for the difficulties youth may experience in adjusting to the new home, it may be possible to prevent mental and behavioral health problems from progressing to a clinically significant level.

Given the present findings, future research examining maltreatment in relation to mental health should be as comprehensive as possible in its measurement of maltreatment and analytic approach. This includes measurement of the dimensions of maltreatment measured in the current study (type, frequency, and severity), and potentially other dimensions not assessed in the current study, such as relation to the perpetrator and the developmental period(s) in which maltreatment occurred. Comprehensive assessment of maltreatment should also include statistical models that simultaneously account for each dimension when examining the association between maltreatment and adjustment. As shown in the current study, trying to capture the entirety of foster care youths’ maltreatment experiences with a single variable or dimension may result in a an incomplete understanding of the relation between maltreatment and a given outcome. Rather, methods should be used that incorporate and account for each dimension simultaneously. This can be achieved through the use of measurement model, such as in the current study, or other comprehensive methods such as latent class analysis (for review, see Rivera, Fincham, & Bray, 2017). Particular attention should be given to the relation between neglect, especially neglect severity, in relation to mental health outcomes. Whereas previous studies have found that childhood neglect is associated with internalizing symptoms but not externalizing symptoms (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002), the present study found the opposite. This contradictory finding indicates the need for replication studies that examine the link between neglect severity and internalizing and externalizing symptoms utilizing similarly rigorous methodology.

Additionally, although maltreatment experiences may be related to some placement changes, others may be determined by factors unrelated to maltreatment. Future studies should explore other reasons for placement change in relation to mental health outcomes for foster care youth. A study by James (2004) found that systems or policy-related factors, such as moving siblings together and foster facility closure, and foster family-related factors, such as moves or deaths of caregivers, account for over 80% of placement changes in foster care. It is possible that our failure to account for the reasons why youth moved could help explain the lack of relation between maltreatment exposure and placement changes, or might help to develop other models for why youth demonstrate mental and behavioral health difficulties. Future research that works to increase understanding in this area of study may also have implications for policy, such as helping those working in the foster care system to identify which children may be more at risk for mental and behavioral problems if they change placements.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Mental Health [RO1 Grant MH079252-03, 2011], and the National Institutes of Child Health and Development [F31 Grant HD088020-01A1, 2017].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, & O’Brien N. (2007). Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 393–415. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, & Patterson CJ (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72, 549–568. 10.1111/1467-8624.00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Gary D, McLaughlin KA, & Keyes KM (2017). Trauma exposure and externalizing disorders in adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 755–764. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey Family Programs (2005). Improving family Foster Care: Findings from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. Seattle, WA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Cho B, & Jackson Y. (2016). Self-reported and case file maltreatment: Relations to psychosocial outcomes for youth in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 241–247. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2005). Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 409–438. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vézina D, Coleman K, Milne L, Sell J, & Daigneault I. (2011). Trauma experiences, maltreatment-related impairments, and resilience among child welfare youth in residential care. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9, 577–589. 10.1007/s11469-011-9323-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Flaspohler P, Katz KH, Saunders L, & Tebes JK (2006). Changes in placement among children in foster care: A longitudinal study of child and case influences. Social Service Review, 80, 398–418. 10.1086/505554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, ... Mallah K. (2017). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35, 390–398. 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S, & Widom C. (2009). Does out-of-home placement mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and adult criminality? Child Maltreatment, 14, 344–355. 10.1177/1077559509332264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, & the LONGSCAN Investigators (1997). Modified maltreatment classification system (MMCS). Retrieved from:http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/. [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, & Bangdiwala SI (2005). Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 575–595. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics, 167, 614–621. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Mannering AM, Van Scoyoc A, & Graham AM (2013). A translational neuroscience perspective on the importance of reducing placement instability among foster children. Child Welfare, 92, 9–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, Jackson Y, & Brown S. (2016). Associations between maltreatment history and severity of substance use behavior in youth in foster care. Child Maltreatment, 21, 298–307. 10.1177/1077559516669443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, Jackson Y, Tunno AM, & Hambrick EP (2017). The blind men and the elephant: Identification of a latent maltreatment construct for youth in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 98–108. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, & Janson S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373, 68–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS Jr., Ko SJ, ... Fairbank JA (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare, 90, 91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick EP, Oppenheim-Weller S, N’zi AM, & Taussig HN (2016). Mental health interventions for children in foster care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 65–77. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildyard KL, & Wolfe DA (2002). Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26, 679–695. 10.1016/S01452134(02)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P, & Gorey KM (2004). Historical, developmental, and behavioral factors associated with foster care challenges. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21, 117–135. 10.1023/B:CASW.0000022727.40123.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PA (2004). Retrospective measurement of childhood sexual abuse: A review of instruments. Child Maltreatment, 9, 201–217. 10.1177/1077559504264264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffhines L, Tunno AM, Cho B, Hambrick EP, Campos I, Lichty B, et al. (2016). Case file coding of child maltreatment: Methods, challenges, and innovations in a longitudinal project of youth in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, & Kotch JB (2006). Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics, 118, 933–942. 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Gabrielli J, Tunno AM, & Hambrick EP (2012). Strategies for longitudinal research with youth in foster care: A demonstration of methods, barriers, and innovations. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(7), 1208–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Gabrielli J, Fleming K, Tunno AM, & Makanui PK (2014). Untangling the relative contribution of maltreatment severity and frequency to type of behavioral outcome in foster youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1147–1159. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S. (2004). Why do foster care placements disrupt? An investigation of reasons for placement change in foster care. Social Service Review, 78(4), 601–627. 10.1086/424546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James S, Landsverk J, & Slymen DJ (2004). Placement movement in out-of-home care: Patterns and predictors. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 185–206. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CR, Carlson EA, & Egeland B. (2006). The impact of foster care on development. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 57–76. 10.1017/S0954579406060044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Granic I, & Lamm C. (2006). Behavioral differences in aggressive children linked with neural mechanisms of emotion regulation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 164–177. 10.1196/annals.1376.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Lau A, English DJ, Briggs E, Newton RR, Romney S, ... Dubowitz H. (2005). Measuring the severity of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 553–573. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT (2005). Advances in research definitions of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 425–439. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis RA, Leschied AW, Chiodo D, & O’Neill A. (2008). The relationship of child neglect and physical maltreatment to placement outcomes and behavioral adjustment in children in foster care: A Canadian perspective. Child Welfare, 87, 5–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae JS, Chapman MV, & Christ SL (2006). Profile of children investigated for sexual abuse: Association with psychopathology symptoms and services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 468–481. 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2012). Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1151–1160. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, & Landsverk JA (2000). Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(10), 1363–1374. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald SH, Heil K, & Goldbeck L. (2010). History of maltreatment and mental health problems in foster children: A review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 462–472. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SE (1996). Placement stability and inclusive practice in foster care: An empirical study. Children and Youth Services Review, 18, 589–601. 10.1016/0190-7409(96)00025-4 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Kessler RC, & Williams J. (2005). Findings from the Northwest foster care alumni study. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor LJ, Skriner LC, Roesch S, & Litrownik AJ (2010). Trajectories of behavioral adjustment following early placement in foster care: Predicting stability and change over 8 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 464–473. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv T, Taussig HN, Culhane SE, & Garrido EF (2010). Cumulative risk exposure and mental health symptoms among maltreated youth placed in out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 742–751. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding RE, Fried C, & Britner PA (2000). Predictors of placement outcomes in treatment foster care: Implications for foster parent selection and service delivery. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9, 425–447. 10.1023/A:1009418809133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, & Kamphaus RW (2004). Behavior assessment system for children (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera P, Fincham F, & Bray B. (2017). Latent classes of maltreatment: A systematic review and critique. Child Maltreatment, 23, 3–24. 10.1177/1077559517728125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DM, Alessandrini EA, Feudtner C, Mandell DS, Localio AR, & Hadley T. (2004). Placement stability and mental health costs for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 113(5), 1336–1341. 10.1542/peds.113.5.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, McLeer SV, & Dixon JF (2000). Sexual abuse characteristics associated with survivor psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 951–964. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, & Testa MF (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 227–249. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer RR, Johnson SB, & Minkovitz CS (2017). Medical complexity and placement outcomes for children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 285–293. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steen JA, & Harlow S. (2012). Correlates of multiple placements in foster care: A study of placement instability in five states. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6, 172–190. 10.1080/15548732.2012.667734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stott T. (2012). Placement instability and risky behaviors of youth aging out of foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29, 61–83. 10.1007/s10560-011-0247-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, & Ormrod R. (2010). Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 323–330. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wert M, Mishna F, Trocme N, & Fallon B. (2017). Which maltreated children are at greatest risk of aggressive and criminal behavior? An examination of maltreatment dimensions and cumulative risk. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 49–61. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villodas MT, Litrownik AJ, Newton RR, & Davis IP (2015). Long-term placement trajectories of children who were maltreated and entered the child welfare system at an early age: Consequences for physical and behavioral well-being. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 46–54. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villodas MT, Cromer KD, Moses JO, Litrownik AJ, Newton RR, & Davis IP (2016). Unstable child welfare permanent placements and early adolescent physical and mental health: The roles of adverse childhood experiences and post-traumatic stress. Child Abuse & Neglect, 62, 76–88. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamser-Nanney R. (2016). Examining the complex trauma definition using children’s self-reports. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 9(4), 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskaya S, Armstrong MI, & McNeish R. (2011). Children placed in out-of-home care: Risk factors for involvement with the juvenile justice system. Violence and Victims, 26, 231–245. 10.1891/0886-6708.26.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]