Abstract

Nursing care: The term nursing care means different things to different people. The authors of these AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Nursing Care Guidelines define nursing care as any interaction between the cat and the veterinary team (veterinarian, technician or nurse, receptionist or other support staff) in the clinic, or between the cat and its owner at home, that promotes wellness or recovery from illness or injury and addresses the patient’s physical and emotional wellbeing. Nursing care also helps the sick or convalescing cat engage in activities that it would be unable to perform without help.

Guidelines rationale: The purpose of the Guidelines is to help all members of the veterinary team understand the basic concepts of nursing care, both in the clinic and at home. This includes methods for keeping the patient warm, comfortable, well nourished, clean and groomed. The Guidelines provide numerous practical tips gleaned from the authors’ many years of clinical experience and encourage veterinary team members to look at feline nursing care in ways they previously may not have considered.

Overarching goal: The primary goal of feline-friendly nursing care is to make the cat feel safe and secure throughout its medical experience.

The art of nursing care

Veterinary medicine is a combination of science and art. Science uses research evidence and data to guide it, while the art of healing relies on clinical experience, observation, patient- or client-directed feedback and the ability to interpret the patient’s state of mind. The patient’s behavioral response to treatment is the central focus in the art of nursing care. To provide optimal support to a well, sick, injured or recovering cat, the art of nursing care is as important as medical science.

Most cat owners can readily detect which members of the veterinary team truly connect and exhibit empathy with their cats. Veterinary team members who apply both the art and science of veterinary nursing care will not only deliver optimal healthcare to the cat but earn the confidence and appreciation of the practice’s clients. Involving the cat owner is a key aspect of successful feline nursing care and requires client education, guidance and support from the veterinary team.

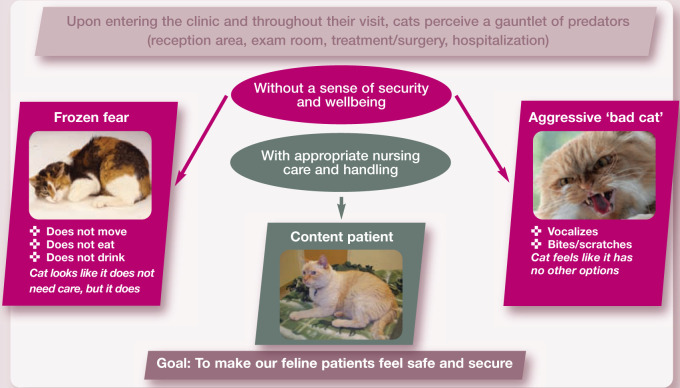

The previously published AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines provide essential primary information regarding the importance of reducing the stress that cats experience before, during and after the veterinary visit. 1 These Feline-Friendly Nursing Care Guidelines supplement the recommendations of the predecessor Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines by placing greater emphasis on the art of veterinary medicine delivered by the veterinary team in the clinic and by the cat owner at home. The primary goal of these Guidelines is to make the cat feel safe and secure throughout its medical experience. By making the cat feel safe and secure, many challenges of handling the feline patient subside or disappear altogether (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ensuring a sense of safety and security is the ultimate goal for managing feline patients in the veterinary clinic. When cats do not feel safe and secure, they display behaviors associated with fear or aggression. Both fear-induced withdrawal (left-hand arrow) and aggression (right-hand arrow) make treatment difficult or impossible. In addition, the physiologic effects of stress impair recovery from illness or injury. ‘Frozen fear’ and ‘Content patient’ images courtesy of Hazel Carney. ‘Aggressive “bad cat”’ ©iStockphoto.com/Anna Sematkina

While most veterinary medical guidelines address the veterinarian, these Guidelines contain nursing care concepts and methods that will also benefit other members of the veterinary team, especially the veterinary technician/nurse. An appreciable number of veterinarians are not comfortable working with cats or do not consider the feline patient to be their first preference. An important goal of these Guidelines is to provide practical recommendations for veterinarians and other members of the veterinary team who find working with cats challenging. Many feline practitioners will find that the Guidelines cover familiar territory. However, the authors hope to provide insights that even experienced clinicians may find helpful.

Clinical improvement in the hospital is only one aspect of treatment success. The ability of the cat owner to provide a continuum of care at home will contribute substantially to a successful case outcome. Thus a key focus of these Guidelines is how to involve the owner in the proper handling of the cat, both in the clinic and at home following discharge. The veterinary team that fails to provide home-care education or initiate communication with the cat owner after discharge may compromise even the best hospital treatment.

Making the cat feel safe and secure

Understanding fear and stress from the cat’s perspective

Anticipating stressful situations

Cats are notoriously sensitive to their surroundings and have a well developed fight-or-flight response. These self-protective responses, normally essential for survival, may be detrimental in a veterinary clinic or domestic setting or when they persist for a prolonged period of time. Unfamiliar circumstances (see box below) that cats encounter in veterinary clinics may lead to the adverse effects of anxiety and fear. These adverse effects suppress normal behaviors (such as rest and feeding), and increase vigilance, hiding and dysfunctional signs such as anorexia, vomiting and diarrhea or even lack of elimination.2,3 Undesirable physiologic responses to stress include hyperglycemia, decreased serum potassium concentrations, elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase concentrations, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, erratic response to sedation and anesthesia, immunosuppression, hypertension and cardiac murmurs.4–6 These changes can complicate clinical evaluation and treatment of cats, and prolong hospitalization.

While the veterinary team cannot eliminate all stressors, it can identify at least some factors to modify or eliminate. The Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines contain more information on environmental factors affecting hospitalized cats. 1

Recognizing fear and anxiety

Fear and anxiety in cats may first manifest as changes in ear position, eyes and facial expression, body posture, sweating from the paw pads, and tail movement. Fearful cats may attempt to escape. Vocalization (eg, mewing, growling, hissing, spitting) may indicate an escalating stress reaction. Some cats then show overtly aggressive behavior such as biting, scratching or attacking. Others respond to fear and anxiety by ‘freezing’, whereby they become immobile, silent and wide-eyed, or by engaging in displacement behaviors such as frantic grooming. Distinguishing behaviors associated with fear and anxiety from those associated with pain may not be easy. The Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines contain more information about recognition of fear and anxiety. 1

Appropriate responses to the fearful and anxious cat

Avoiding excessive restraint of the fearful cat is very important. A heavy-handed approach will most likely increase the cat’s anxiety and make handling even more difficult. The clinician, veterinary assistants and cat owner should remain calm and patient. The veterinary team should be flexible and willing to tailor the visit to the needs of the individual patient. The staff should adopt an alternate approach to accomplishing the goals of the visit if the cat is fearful and resists handling. This may include sedation or a period when medical activity temporarily stops in order to allow the cat to calm down. If the cat’s behavior suggests the presence of pain, however slight, provide analgesia and reassess the cat’s response.

Benefits of reducing in-clinic stress in cats

Improved patient outcomes

Favorable response of cats to a synthetic analog of feline facial pheromone (FFP) is an example of how nursing care can improve patient outcomes in a veterinary hospital setting. Hospitalized cats that had synthetic FFP applied to a towel in their cages significantly increased both their grooming behaviors and food intake. 7 Exposing cats to synthetic FFP during premedication activities prior to anesthesia also made the cats calmer at the time of venous catheterization. 8

Anesthetic complications are more common in cats than dogs and are associated with health status, age, weight, procedure type and urgency.9,10 Careful attention to patient assessment and management before anesthesia can reduce perioperative complications. However, the cat’s response to fear and anxiety may complicate or even preclude a thorough preanesthetic evaluation. Reducing or pre-empting stress in hospitalized cats can facilitate the presurgical examination and preoperative laboratory testing, ultimately improving patient safety.

Satisfied owners and increased feline visits

Recently published studies have revealed an underutilization of veterinary healthcare for cats in the US and Canada. While cat owners generally have a higher level of education than dog owners, they are less likely to take their cat to the veterinarian than dog owners. 11 Focus groups found that one of the most important factors contributing to fewer feline visits to veterinarians is signs of stress exhibited by the cat. 12 Both the difficulty of getting a cat into a carrier, and the vocalization and physical signs of tension displayed by cats while in the veterinary hospital waiting room and during examinations, distress owners. As a result, many cat owners avoid the unpleasant aspects of the veterinary hospital visit by simply not taking their cat to the veterinarian. Improving the cat and owner experience before, during and after the clinic visit, including hospitalization, will encourage cat owners to present their pets more frequently for wellness exams and earlier in the course of disease.

Improved safety and job satisfaction for the veterinary team

Aggression is one of the most commonly reported feline behavior problems. Fear and pain encountered in the clinic are common sources of feline aggression. Attacks on veterinary staff typically involve biting or scratching. The infection rate in untreated injuries from cat attacks is high, ranging from 30–50%.13,14 Hand wounds are especially prone to infection. Improving the hospitalization experience for the feline patient decreases fear-based aggression, and better recognition and management of pain reduces pain-based aggression.

Decreasing fear and anxiety in the hospitalized cat has other benefits. Improved handling and housing of cats reduces stress not only for feline patients but also for the veterinary team. Staff members may experience increased job satisfaction if patients show signs of improved wellbeing, better case outcomes and less stress-induced negative behavior. Finally, reduced time required for handling fractious and uncooperative cats improves treatment efficiency and work flow in the veterinary practice.

Nursing care in the clinic: a ‘cat’s eye’ view

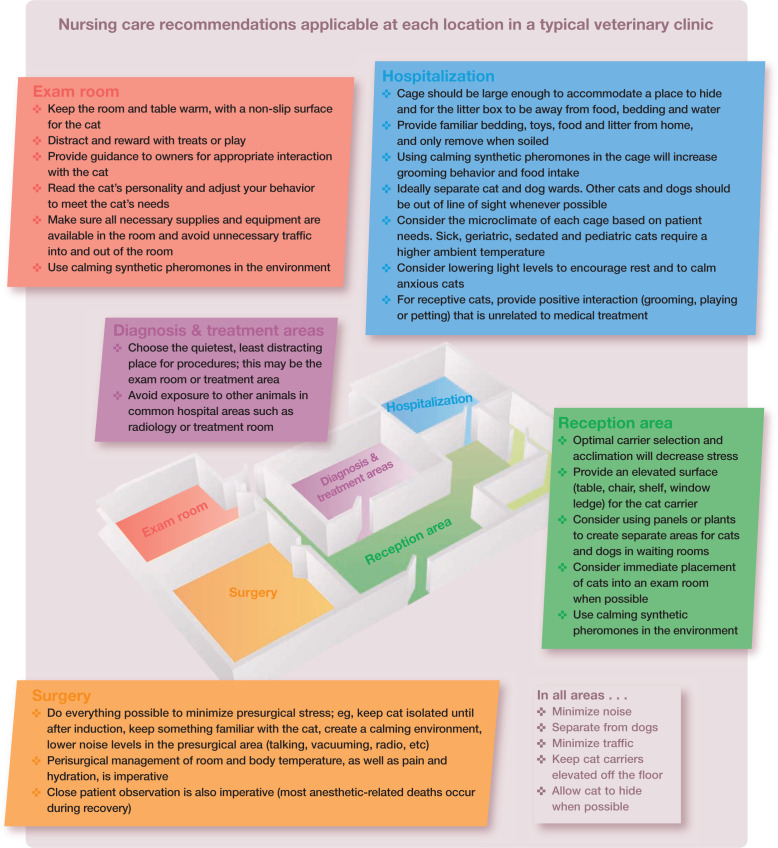

Actions that reduce the stress from the cat’s perspective as it progresses through the clinic can be implemented at each location within the clinic (see box below).

Veterinary team considerations

Use a team approach

Monitor and respond appropriately to any evidence of stress in a feline patient at every stage of the hospital visit; this is an approach that will help improve safety and efficiency for staff and cat owners. To minimize the patient’s stress, each member of the veterinary team plays a role in the cat’s experience from the time it enters the door until it leaves the clinic, and even afterward in monitoring home care. The entire veterinary team should understand what makes a patient’s visit go smoothly and without mishap. This broad umbrella of responsibility includes educating cat owners about stress-free transportation of their cats to the clinic, utilizing patient-friendly examination techniques, recognizing feline behavior patterns, and creating a low-stress home environment for the patient.

The veterinary team should have a common interest in practicing safe and effective handling techniques, in sharing knowledge to maintain a high level of service provision and in creating a culture of continuous improvement.

Optimize the value of the veterinary technician or nurse

The veterinary technician/nurse plays a vital role within the team. Involving the technician can help improve efficiency and productivity in feline case management. When employed to their full potential, technicians can carry out many tasks typically performed by the veterinarian and can delegate certain duties to other team members. An experienced technician understands the basic needs of the cat, normal feline behavior, feline disease processes, and subtle clinical signs that owners may overlook. For many technicians, effective communication with owners is a core competency and a skill that increases in value when the veterinarian’s time is limited. By maintaining an open dialogue with the cat owner, the technician is well positioned to alert the veterinarian to any concerns the owner may have regarding their cat.

Recommendations for reducing stress in the reception area

Instruct reception personnel on providing suggestions to owners for optimal carrier design and transportation of the patient (see Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines for additional details). 1

Provide an elevated surface (eg, table, shelf, chair, bench) to keep cat carriers off the floor.

Separate dogs from cats or minimize time in the waiting room to avoid encounters between canine and feline patients.

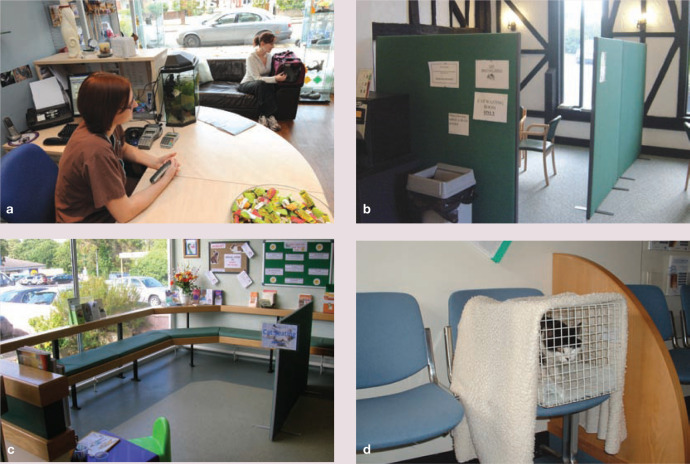

Figure 2 shows features of a cat-friendly reception area.

Figure 2.

(a) Reception personnel are readily accessible to the cat owner in order to respond to questions or concerns. (b) The waiting room includes a separate area for owners who want additional privacy or to isolate their cats from other pets or clients. (c) Bench seating allows for elevation of the cat carrier and placement next to the owner. (d) A towel draped over the cat carrier provides an impromptu hiding place in the reception area. Images courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Recommendations for reducing stress in the exam room

Provide a warm, quiet room with a comfortable, non-slip examination surface.

Ensure that all necessary supplies and equipment are immediately available to avoid unnecessary traffic into and out of the room and interruption of the examination.

Evaluate the cat’s personality and temperament at the time of presentation and adjust the approach accordingly.

Offer guidance on how the cat owner can appropriately interact with the patient during the examination (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The cat owner’s presence during the examination can help minimize the cat’s anxiety in response to environmental or procedural stress. Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Recommendations for reducing stress during the physical exam

The mindset and physical approach of the veterinary team is critical to successful interaction with cats. Be patient, calm, positive and confident.

Taking time with feline patients actually improves efficiency. A hurried approach may create anxiety in the patient or result in an incomplete examination or treatment. If the cat remains calm and relaxed during the examination, its owner will gain confidence in the clinician.

Note in the patient’s medical record approaches that have previously worked or not worked.

Open the carrier door or remove the carrier top to allow the cat to exit on its own. This will give the cat a sense of control and safety. Avoid forceful removal of the cat from the carrier. Food or toys may entice cats to exit that do not do so voluntarily.

Examine the cat where it wants to be examined. This may be on the exam table, floor, scale or in the carrier.

The cat may perceive someone staring directly into its eyes as a threat. Slow blinking conveys trust and friendliness. 15

If a cat becomes tense or agitated, temporarily interrupt the exam and allow the cat to relax. In a busy practice, it is tempting to overlook this simple approach.

The most important thing to remember when examining a cat is not to overreact with forcible restraint or correction of resistant behavior. Cats that exhibit minor demonstrations of anxiety, such as fidgeting, may respond best if the clinician continues the examination in a neutral, deliberate manner.

Always look for an opportunity to reward positive behavior with a treat or petting. This encourages the cat to relax. Positive behaviors may be subtle, such as a change in facial expression or relaxation of body tension.

Recommendations for reducing stress in diagnosis and treatment areas

Cats can experience considerable pain and distress from diagnostic or emergency procedures such as repeated venipuncture, cystocentesis or placement of a large-bore central line. 16 The effect of these interventions can be both cumulative and additive when the same procedure is repeated or if several different procedures are performed in succession. Use of analgesics such as transmucosal buprenorphine may greatly facilitate execution of these tasks. If appropriate physical restraint has failed, if the cat is already in pain, or if the intervention required will be repeated or painful (eg, wound debridement, bandaging), chemical sedation or general anesthesia combined with analgesic agents is appropriate.

Tips for reducing stress during diagnosis and treatment include:

Location Choose a quiet area for performing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.

Positioning the patient Place the cat on a soft, non-slip surface and in the most natural position for the planned procedure. For example, perform cystocentesis in the position that is most comfortable for the cat. This may be in a standing position or in lateral instead of dorsal recumbency.

Feline facial pheromone Using synthetic FFP in cages, tables or on blankets in procedure rooms and housing areas 10–15 minutes prior to a procedure produces a calming effect. 8

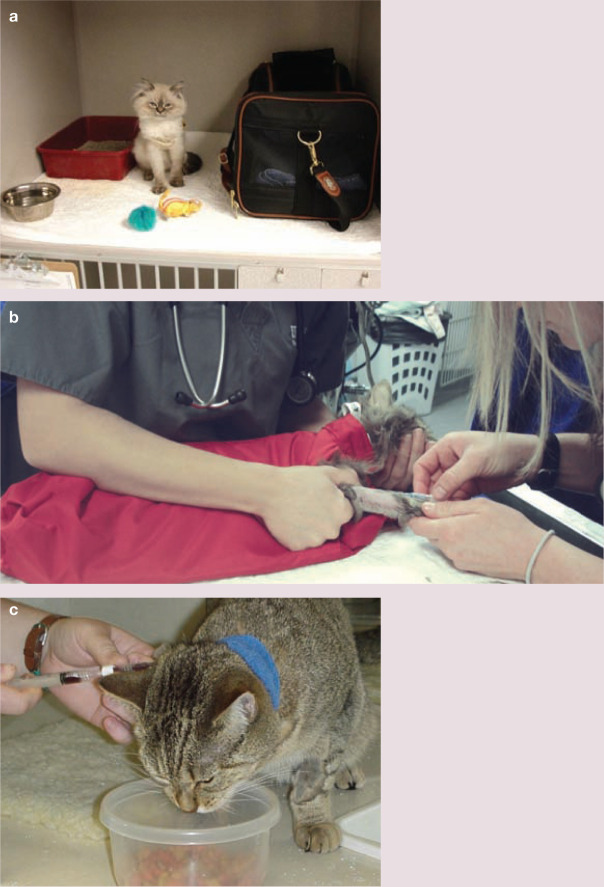

Venipuncture Jugular, cephalic or medial saphenous veins are appropriate choices for blood collection. Medial saphenous vein catheter placement is a good option for short procedures and blood draws. Positioning the cat for venipuncture of the medial saphenous vein usually requires the least restraint and may be the most comfortable for many cats (Figure 4). Shaving is usually not required, making the procedure quicker and removing a step that may alarm or upset the cat.

IV catheter placement Avoid multiple venipunctures by placing an intravenous (IV) catheter for repeated blood samples, fluid therapy and/or IV treatments, or in case emergency access should become necessary. Topical application of local anesthetic creams to desensitize the skin can facilitate catheter placement in non-emergency situations. Two topical anesthetics are available, lidocaine in a liposome-encapsulated formulation and a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine. Minimal systemic absorption occurs after application of either product. 17 Use a minimal amount of restrictive tape to secure catheters. Check tape and bandages frequently to ensure they are not overly tight and have not shrunk after becoming wet. Consider suturing jugular catheters in place and covering them with a small amount of elastic, self-adhesive bandage.

Administering subcutaneous fluids Warming subcutaneous (SC) fluids to the cat’s body temperature can lessen discomfort associated with administration. Warming is usually done using a microwave or a warm water bath. Each veterinary practice should develop a protocol for achieving the correct temperature that avoids burning the patient. To determine the practice protocol, take a bag stored under stable temperature conditions, cut open the access port, and place the bag upright in a container to avoid spillage. Microwave the bag at 15 second intervals. Because the bag has an irregular shape, agitate the contents after each cycle and then insert a thermometer through the open access port until a temperature of approximately 100–102°F (37.8–38.9°C) is reached. Record the power setting and time needed to reach the target temperature in an accessible place, such as next to the microwave or in a written protocol for SC fluid therapy.

Avoid exposure to other animals This includes realistic photos or models of animals (illustrations are preferable).

Figure 4.

Medial saphenous vein catheter placement is a good option for short procedures and blood draws. Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Recommendations for reducing perioperative stress

-

Do everything possible to minimize the cat’s exposure to presurgical stress:

– Keep the cat isolated in a quiet place until after induction;

– Provide a familiar object such as bedding from home or a toy (Figure 5a; also appropriate for the post-surgical environment);

– Create a calming environment by minimizing levels of ambient noise, conversation, or operation of equipment and appliances;

– Use synthetic FFP in the cat’s cage and in the procedure room.

Maintain appropriate perioperative room and body temperature, and ensure adequate pain control and hydration (Figure 5b).

Monitor the patient closely during recovery, which is when most anesthetic-related deaths occur. 10

Figure 5.

(a) Familiar objects create a less threatening presurgical environment. (b) A cat bag provides warmth and gentle restraint. (c) Placement of an IV catheter provides venous access for multiple injection procedures or repeated blood draws, minimizing discomfort in a feline surgical patient. Images courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Recommendations for reducing stress during hospitalization

Environment

Maintain separate cat and dog wards if possible.

Keep patients out of each other’s field of vision.

Maintain low levels of light to calm anxious cats and encourage them to rest.

Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, create a cage environment designed for each individual cat’s needs and preferences.

Use cages large enough to provide a place for the cat to hide and to maintain the litter box separate from food, bedding and water. 18

Litter box size and height must match the cat’s size and mobility (Figure 6). Use the cat’s preferred litter when possible.

Provide familiar bedding, toys, food and litter from home; change bedding only when soiled.

Adjust the microclimate of each cage based on individual needs; sick, geriatric, sedated and pediatric patients require a warmer ambient temperature.

To maintain the cat’s body heat, provide comfortable bedding such as thick towels or fleece, orthopedic bedding or yoga mats.

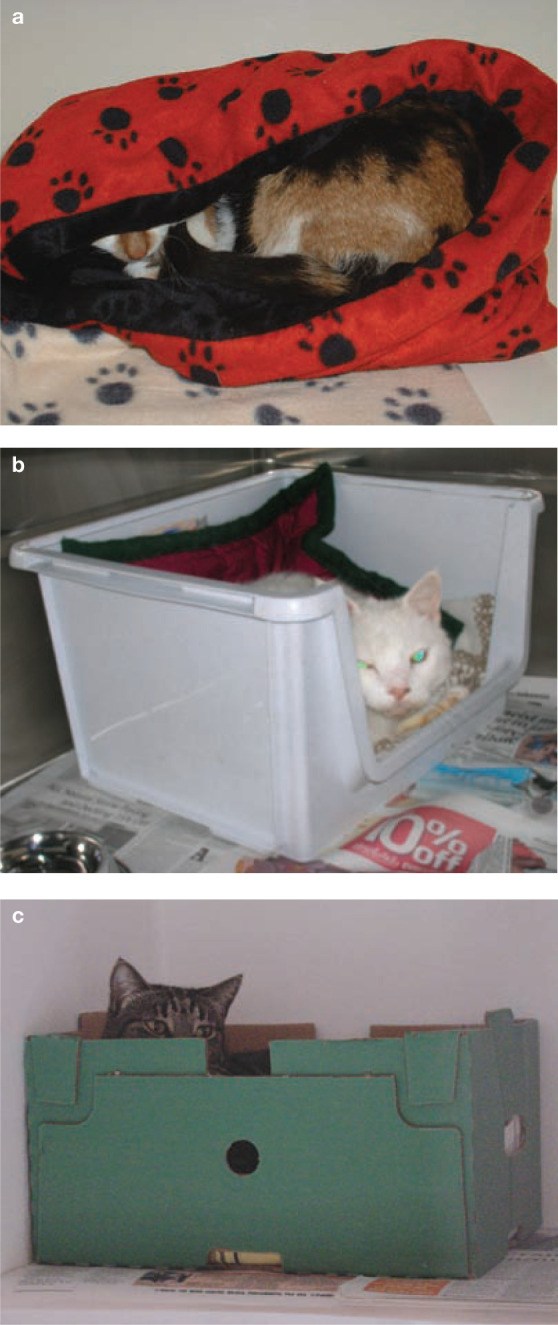

Provide an inside-the-cage hiding place such as a sturdy paper bag, cardboard box, cat bed or carrier (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

A hospitalized cat can readily access a litter box with low sides (a), whereas a high-sided litter box (b) would be much more difficult to access. Images courtesy of Susan Little

Figure 7.

Three examples of inside-the-cage hiding places that provide security for the hospitalized cat. Images courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Cat-friendly equipment and accessories

The following equipment and accessories will help reduce the stress of hospitalization for the feline patient:

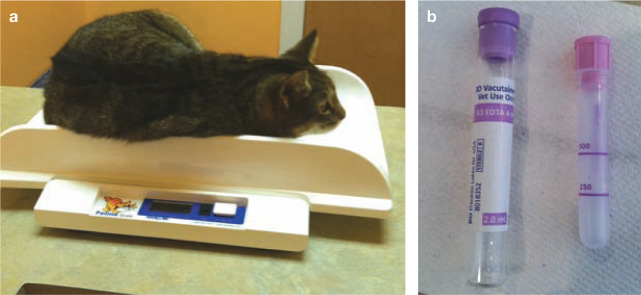

Easy-to-use scale with elevated sides (Figure 8a).

Small, quiet fur clippers.

Small-volume blood collection tubes (Figure 8b).

Large, thick bath towels or fleece for restraint or placement in cages (Figure 9).

Yoga mat material or non-slip rug pads for lining cage bottoms, kennels, or examination tables to provide warmth and non-slip surfaces.

Washable oven or protective gloves designed for handling animals, preferably with long cuffs to protect the handler’s hands and arms.

Cat masks to minimize visual stimulation and calm some cats.

Cat bags for gentle restraint.

Figure 8.

Examples of cat-friendly equipment. (a) Cat scale with elevated sides. (b) Small blood collection tubes. Images courtesy of Dawn Brownlee-Tomasso

Figure 9.

A thick towel or fleece provides warmth and security for the hospitalized cat. Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Feeding

Feed the cat its regular diet during hospitalization. Ask the owner to bring in favorite treats if appropriate.

Start therapeutic diets when the cat returns home and its normal appetite returns.

Flat food dishes, such as small paper plates, and shallow water bowls will improve intake by making food and water more accessible.

Warm canned food to the cat’s body temperature by microwaving or adding warm water. Additions of chicken broth or tuna juice may enhance palatability.

Do not leave food in cages of cats that display food aversion (drooling, licking lips, ignoring the food bowl, vomiting).

Food should always be fresh, provided in small portions and replenished as needed.

Appetite stimulants may be useful in selected cases for brief periods (2 days) in conjunction with the methods outlined above. 19

Figures 10 and 11 illustrate other feeding techniques for the hospitalized cat.

Figure 10.

Hand feeding of small amounts of food, short-term use of appetite stimulants, and petting may encourage convalescent cats to resume eating. Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Figure 11.

Many cats benefit from a feeding tube when other strategies to encourage eating have failed. 19 Note that a soft Elizabethan collar is preferable where available. Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

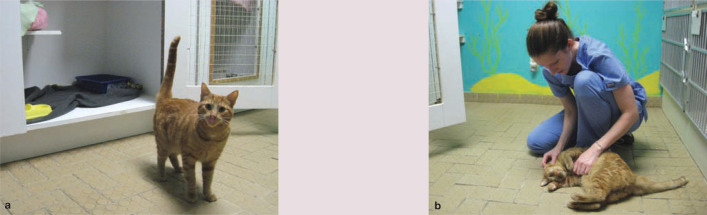

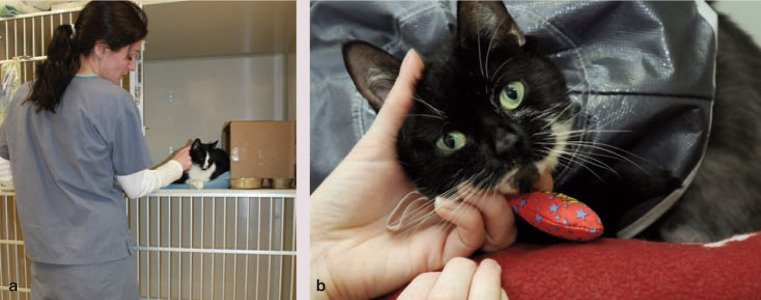

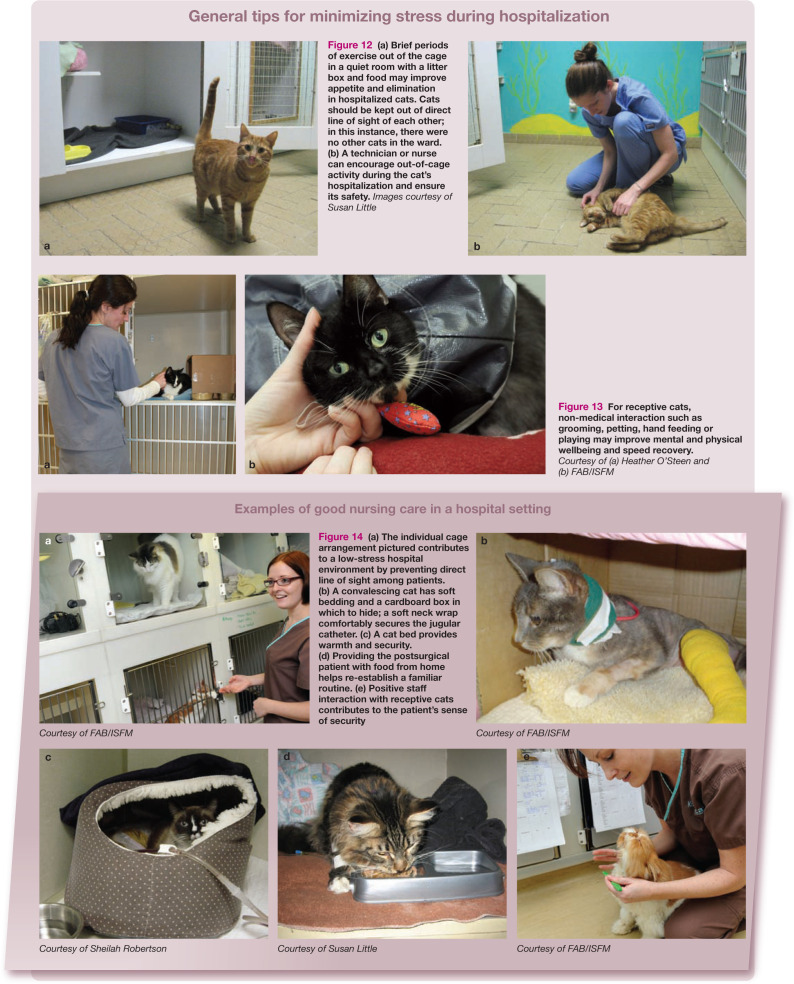

General tips

Figures 12–14 illustrate some general tips that will minimize stress and hasten recovery for cats during hospitalization.

Figure 12.

(a) Brief periods of exercise out of the cage in a quiet room with a litter box and food may improve appetite and elimination in hospitalized cats. Cats should be kept out of direct line of sight of each other; in this instance, there were no other cats in the ward.(b) A technician or nurse can encourage out-of-cage activity during the cat’s hospitalization and ensure its safety. Images courtesy of Susan Little

Figure 14.

(a) The individual cage arrangement pictured contributes to a low-stress hospital environment by preventing direct line of sight among patients. (b) A convalescing cat has soft bedding and a cardboard box in which to hide; a soft neck wrap comfortably secures the jugular catheter. (c) A cat bed provides warmth and security. (d) Providing the postsurgical patient with food from home helps re-establish a familiar routine. (e) Positive staff interaction with receptive cats contributes to the patient’s sense of security

Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Courtesy of Susan Little

Courtesy of FAB/ISFM

Figure 13.

For receptive cats, non-medical interaction such as grooming, petting, hand feeding or playing may improve mental and physical wellbeing and speed recovery. Courtesy of (a) Heather O’Steen and (b) FAB/ISFM

Practical nursing care tips for the veterinary team and cat owner

Pet owner behavior in the exam room

Cats are not alone in experiencing anxiety during a visit to the veterinary clinic. The cat owner who accompanies the patient into the exam room often feels some apprehension as well. When a cat senses its owner’s apprehension, the animal’s anxiety often increases.

The following pointers will help the pet owner to be a calming influence in the exam room:

Avoid human behaviors that, while intended to comfort the cat, may actually increase its anxiety. Examples include clutching the cat, talking or staring in its face, and disturbing or invading its personal space. Human sounds intended to soothe or quiet (like ‘shhhh’) may mimic another cat hissing.

Physical correction such as tapping the cat’s head and delivering stern vocal corrections may startle the cat and provoke the fight-or-flight response. Cat owners and veterinary team members should remember that despite being family members, cats are not human and react differently to discipline.

The cat will dictate when it wants to be handled. In the clinic setting, instruct the owner not to handle or remove their cat from its carrier until a member of the veterinary team requests otherwise.

Reinforce the cat’s positive behavior and ignore negative behavior rather than trying to correct it.

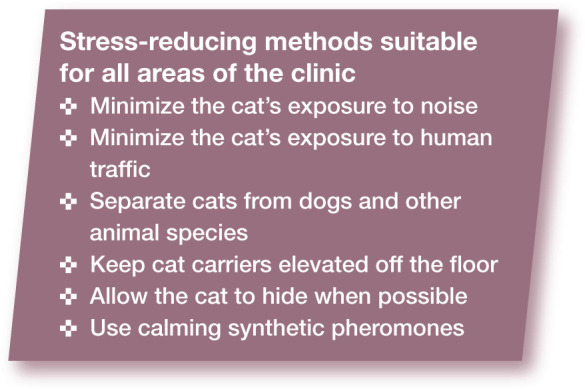

Home care nursing tips for pet owners

The veterinary team’s responsibilities

Successful case outcomes are often dependent on the ability of the cat owner to continue at home the nursing care that began in the clinic. The veterinary team’s responsibility is to ensure that the owner maintains optimal care of the patient at home. Appropriate owner education, guidance and ongoing support by the team can also enable early discharge of the feline patient, which may benefit everyone.

When discussing treatment options with an owner, the technician/nurse may describe drug formulations that are available and ask the owner which option best matches both the cat’s personality and the owner’s physical abilities. If an owner has no prior experience of administering medication, the technician/nurse can offer suggestions, such as a flavored liquid that may be easier to administer than a bitter tablet or a capsule. The technician/nurse may also demonstrate several administration techniques to help owners decide which option might be best for them.

Owner education is especially important because administering home nursing care is not intuitive to most cat owners. The veterinary team can facilitate the process in the following ways:

Reinforce nursing care instructions for the cat owner by providing them verbally and in writing, as well as using available multimedia and online resources; if appropriate, demonstrating techniques (eg, administering medications or SC fluids) can be helpful. An owner instruction sheet that includes the rationale for the patient’s medical treatment, along with follow-up instructions and tips for appropriate home nursing care, will help ensure compliance.

Following the cat’s discharge, communicate with the owner to confirm successful treatment and address unexpected issues.

The pet owner’s role at home

The following nursing care tips will help the cat owner become an extension of the veterinary team after the patient leaves the clinic:

For acute home care, identify a quiet, familiar, private space such as a small enclosure or alcove with good light where the owner can easily access their cat. A small space allows for close monitoring of the cat and provides it with a sense of security.

Establish a routine for administering oral medication to the cat.

A bathroom sink lined with a soft towel or fleece provides an enclosed, secure place for administering medication to a cat.

Give the cat positive reinforcement (eg, treats, brushing, petting) for accepting medication.

Except when medications must be administered with food (eg, phosphate binders), do not use food as an aid to giving medications, especially if this causes aversion and reduces the cat’s food intake.

Forcing the cat to accept medication is stressful for both the owner and the cat. Do not forcibly remove the cat from a hiding place or interrupt eating, grooming or elimination for purposes of administering medication.

Welcome questions and encourage owners to call if they have any concerns about home nursing care, including administering medication. Offer alternate ways (eg, different medication formulations) to accomplish the treatment goal.

Explain to the owner healthy cat behaviors and signs of wellbeing that signal full recovery. Cats that feel good tend to sleep most often in a curled position. They groom themselves, follow a normal routine, interact with their owner, and eat and eliminate regularly.

Avoid things that annoy cats

When an Elizabethan collar is required, use one made of soft material instead of rigid plastic (Figure 15a,b).

Cats do not like tight or restrictive dressings and bandages. Cats like to stretch and move freely. Elastic, self-adhesive and non-restrictive bandages are well tolerated (Figure 15c,d). Most cats prefer a tubular stockinette instead of white zinc oxide tape or non-expandable gauze dressings.

Many cats react negatively to alcohol for skin cleaning or ‘wetting down’ an area prior to venipuncture because they dislike the smell or sudden cold sensation as the alcohol evaporates. Use warm sterile saline or water as an alternative.

Cats mark their territory with facial pheromones and will exhibit this behavior in a hospital cage. They may display facial rubbing of bedding, boxes, cage walls and doors. Avoid cleaning some of the marked areas in the cage.

Cats are well known for cleanliness and attention to grooming. Sick or debilitated cats are typically less able to groom and need caregivers to groom them. Remove any blood or medicinal solutions from the cat’s skin or hair to decrease the personal hygiene the cat must perform. Remove substances that may taste unpleasant to the cat when it grooms.

Figure 15.

A soft Elizabethan collar (a) is more comfortable than a rigid collar (b). A flexible self-adhesive bandage (c) is preferable to a stiff, restrictive bandage (d). Images courtesy of Sheilah Robertson

Summary Points

-

Veterinary practices that care about their feline patients enough to utilize nursing methods that accommodate the specialized needs of cats will reap numerous rewards:

– Veterinary team members will provide better care that facilitates treatment and recovery of their feline patients;

– Owners will appreciate and respond to an approach that emphasizes the cat’s safety and security;

– Veterinarians will earn owner loyalty and will have a more productive, safer and happier veterinary team.

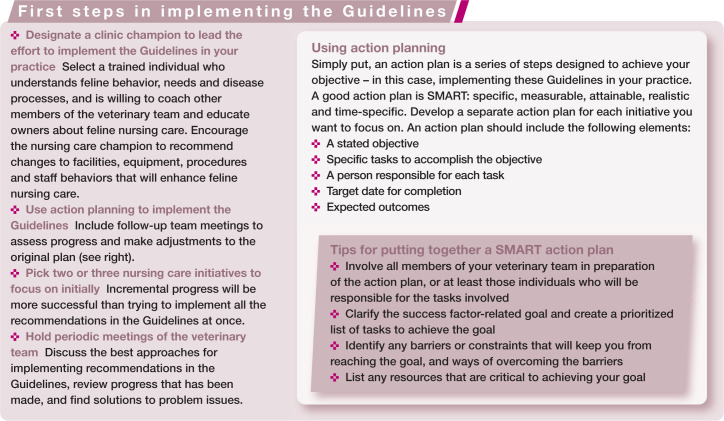

These Guidelines are comprehensive and may seem daunting. However, even small improvements and incremental progress in feline nursing care can pay immediate dividends and start building a culture of skilled and compassionate feline care.

Supplemental Material

Practical Tips for Pet Owners

Portuguese version of the Guidelines

Russian version of the Guidelines

Acknowledgments

The AAFP and ISFM would like to thank Boehringer Ingelheim and Nestlé Purina for their sponsorship of these guidelines and for their commitment to helping the veterinary community develop projects that will improve the lives of cats. Grateful thanks also to all the practices that are photographed within these guidelines.

References

- 1. Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H, Gagnon A-C, Heath S, Landsberg G, et al. AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carlstead K, Brown JL, Strawn W. Behavioral and physiological correlates of stress in laboratory cats. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1993; 38: 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stella JL, Lord LK, Buffington CAT. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greco DS. The effect of stress on the evaluation of feline patients. In: August J, ed. Consultations in feline internal medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1991, p 13. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paige CF, Gordon SG, Roland RM, Bogg M. Prevalence of heart murmurs and occult heart disease in apparently healthy cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009; 234: 1398–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quimby JM, Smith ML, Lunn KF. Evaluation of the effects of hospital visit stress on physiologic parameters in the cat. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 733–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffith CA, Steigerwald ES, Buffington CA. Effects of a synthetic facial pheromone on behavior of cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217: 1154–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kronen PW, Ludders JW, Erb HN, Moon PF, Gleed RD, Koski S. A synthetic fraction of feline facial pheromones calms but does not reduce struggling in cats before venous catheterization. Vet Anaesth Analg 2006; 33: 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brodbelt DC, Pfeiffer DU, Young LE, Wood JLN. Risk factors for anaesthetic-related death in cats: results from the confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities (CEPSAF). Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brodbelt D. Feline anesthetic deaths in veterinary practice. Top Companion Anim Med 2010; 25: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perrin T. The Business of Urban Animals Survey: the facts and statistics on companion animals in Canada. Can Vet J 2009; 50: 48–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Volk JO, Felsted KE, Thomas JG, Siren CW. Executive summary of the Bayer veterinary care usage study. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011; 238: 1275–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westling K, Farra A, Cars B, Ekblom AG, Sandstedt K, Settergren B, et al. Cat bite wound infections: a prospective clinical and microbiological study at three emergency wards in Stockholm, Sweden. J Infect 2006; 53: 403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Palacio J, León-Artozqui M, Pastor-Villalba E, Carrera-Martín F, García-Belenguer S. Incidence of and risk factors for cat bites: a first step in prevention and treatment of feline aggression. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Natoli E, Baggio B, Pontier D. Male and female agonistic and affiliative relationships in a social group of farm cats (Felis catus L.). Behav Processes 2001; 53: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. AAHA/AAFP Pain Management Guidelines Task Force Members, Hellyer P, Rodan I, Brunt J, Downing R, Hagedorn JE, Robertson SA. AAHA/AAFP pain management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 466–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner KA, Gibbon KJ, Strom TL, Kurian JR, Trepanier LA. Adverse effects of EMLA (lidocaine/prilocaine) cream and efficacy for the placement of jugular catheters in hospitalized cats. J Feline Med Surg 2006; 8: 141–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kry K, Casey R. The effect of hiding enrichment on stress levels and behaviour of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) in a shelter setting and the implications for adoption potential. Animal Welfare 2007; 16: 375–383. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chan DL. The inappetent hospitalised cat: clinical approach to maximizing nutritional support. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 925–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Practical Tips for Pet Owners

Portuguese version of the Guidelines

Russian version of the Guidelines