Abstract

In contemporary society, social media pervades every aspect of daily life, offering significant benefits such as enhanced access to information, improved interconnectivity, and fostering community among its users. However, its usage, particularly when excessive, can lead to negative psychological outcomes, including the prevalence of social media addiction (SMA) among adolescents. While extensive research has been conducted on the phenomenon of SMA, there is a notable paucity of studies examining the link between individual levels of self-compassion and susceptibility to SMA. This study aims to investigate the correlation between self-compassion and SMA in college students, while also examining the potential mediating influence of gratitude. The study sampled 1131 college students who engaged in an anonymous online survey. This survey utilized the Chinese translations of the Self-Compassion Scale, Gratitude Questionnaire, and SMA Scale. For data analysis, validated factor analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® AMOS™ version 23. Correlation analyses were carried out with IBM® SPSS® version 22.0, and the PROCESS macro (Model 4) was employed to assess path and mediation effects. Higher levels of positive self-compassion were found to mitigate the effects of SMA, while elevated levels of negative self-compassion were associated with an increase in such addiction. The study further revealed that gratitude played a partial mediating role in the relationship between self-compassion and SMA. Specifically, positive self-compassion can reduce symptoms of SMA by enhancing levels of gratitude, whereas negative self-compassion may worsen these symptoms by diminishing gratitude. Positive self-compassion is instrumental in fostering personal growth among college students, with gratitude serving as a significant mediator in reducing SMA.

Keywords: gratitude, mediating role, self-compassion, social media addiction, university students

1. Introduction

Social media has become an integral part of contemporary society.[1–3] As of this writing, daily users of social media surpass 53% of the global population, amounting to approximately 4.5 billion individuals, with this figure nearing 80% in more developed nations.[1] The continual introduction of new features and development of personalized content have significantly enhanced the appeal of social media platforms. Nonetheless, the multifaceted functionalities of social media have also heightened its “stickiness” – the frequency at which users revisit social media sites – potentially leading to social media addiction (SMA).[4]

SMA is defined as a sociopsychological phenomenon where individuals lose control over the duration and intensity of their social media use, leading to both psychological and physical distress.[5] Based on the biopsychosocial model,[6] the 6 hallmark symptoms of SMA are as follows: an overwhelming focus on social media use (salience); utilizing social media to enhance positive feelings or mitigate negative ones (mood modification); the need to spend progressively more time on social media to achieve the same level of satisfaction (tolerance); experiencing symptoms such as irritability and depression when access is restricted (withdrawal); diminished performance across various aspects of life (conflict); impaired self-regulation skills, resulting in an inability to curtail usage (relapse)[7–10]; and deterioration in personal relationships.

Research has demonstrated that SMA is intricately linked to a range of adverse outcomes, including emotional depression, identity issues, social comparisons, academic and work difficulties, career obstacles, sleep deprivation, deteriorating physical health, and social anxiety leading to isolation.[10–13] Mental health disorders are significant predictors of SMA, encompassing depression, loneliness,[14] social anxiety,[15] dark-triad personality traits,[16] attachment styles,[17] narcissism,[18] and compulsive selfie-taking behavior.[19] Moreover, personality traits have been found to be closely associated with SMA, with a particular negative correlation between empathy and SMA.[20] Individuals who are introverted and less empathetic are at a higher risk of developing SMA.[21] Conversely, self-esteem has been positively linked with SMA, whereas the capacity to resist external pressures and maintain authenticity appears to lower the risk of addiction.[22] The field of positive psychology has also explored SMA, highlighting its detrimental effects on happiness and well-being.[23,24]

College students represent a particularly vulnerable demographic for SMA, experiencing negative repercussions such as diminished happiness, poor academic achievement, and sleep disturbances. Despite growing academic interest in SMA among college students, there remains a significant gap in research regarding the interplay between positive psychology elements, specifically self-compassion, gratitude, and SMA. Thus, this study aims to fill this gap by investigating how positive self-compassion, negative self-compassion, and gratitude can counteract SMA through the lens of positive psychology, thereby contributing to the healthy development and well-being of college students.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical background

The Interaction of Person–Affect–Cognition–Execution (I-PACE) model[25] elucidates the complex interplay among various factors, including an individual’s biopsychosocial and sociodemographic characteristics (like genetics, personality traits, psychopathologies, and motivations for usage), affective and cognitive processes (such as attention focus, emotion regulation, and coping strategies), and executive functions (including inhibitory control and working memory), in contributing to addictive behaviors. The I-PACE model underscores the critical role of personal background factors, positioning self-compassion as a trait-like stable characteristic.[26] Moreover, gratitude, as a component of the affective system, interacts with self-compassion, yielding varying impacts on behavioral outcomes. Consequently, self-compassion and gratitude are seen as key predictors and mediators in preventing the development of smartphone addiction among adolescents.[25]

There was a negative correlation observed between self-compassion and anxiety, depression, and self-criticism, whereas a positive correlation was found between self-compassion and happiness, optimism, and well-being. Additionally, a negative correlation between Internet addiction and depression and low self-esteem was identified, suggesting that self-compassion can serve as a protective factor against these forms of psychopathology.[27]

Based on the theory of affective experience, the perception of the benefits and assistance provided by others is considered a key factor in determining one’s gratitude.[28] Positive self-compassion enables individuals to accurately perceive their emotions when experiencing pain, without magnifying the intensity of their distress or sadness.[29] Therefore, it is hypothesized that individuals with high levels of positive self-compassion will have a heightened ability to genuinely experience gratitude when receiving favors and assistance. On the contrary, negative self-compassion can have a negative impact on gratitude.[30]

2.2. Self-compassion influences social media addiction

The I-PACE model[25] offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate interactions between a variety of factors that contribute to addictive behaviors. These factors encompass an individual’s biopsychosocial and sociodemographic attributes, such as genetics, personality traits, psychopathologies, and reasons for engagement, as well as affective and cognitive processes including focus of attention, emotion regulation, and coping mechanisms. Additionally, the model considers the role of executive functions, like inhibitory control and working memory. Central to the I-PACE model is the emphasis on the pivotal role of personal background factors, with self-compassion identified as a stable, trait-like characteristic.[26] Furthermore, gratitude, as part of the affective system, interacts with self-compassion to influence behavioral outcomes in various ways. Therefore, self-compassion and gratitude are highlighted as crucial predictors and mechanisms for mitigating the risk of smartphone addiction among adolescents.[25]

Positive self-compassion embodies an individual’s accepting and gentle approach toward negative experiences,[31] playing a significant role in mitigating SMA. Studies indicate that positive self-compassion fosters a benevolent self-perspective,[32] enabling individuals to maintain a clear and balanced mindset, remain anchored in the present, and steer clear of engulfing negative emotions.[33,34] This approach helps alleviate the physical and psychological exhaustion stemming from prolonged and excessive engagement with social media, thereby easing SMA symptoms. In contrast, negative self-compassion is characterized by a self-critical and blaming stance toward one’s feelings of frustration and helplessness following adverse events.[31] This attitude can lead individuals to dwell on distressing emotions, exacerbating feelings of depression,[35] amplifying despair and helplessness,[36] diminishing interpersonal interactions, and fostering an excessive dependence on the Internet – ultimately escalating SMA.

Several studies have examined the impact of self-compassion on SMA. Iskender and Akin[27] research on the connection between self-compassion and social network addiction reveals that aspects of self-compassion, such as self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, exhibit a negative correlation with Internet addiction. Conversely, dimensions like self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification show a positive correlation with Internet addiction. Notably, self-kindness and mindfulness are inversely predictive of Internet addiction, while self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification positively forecast Internet addiction levels. Despite these insights, there remains a dearth of research specifically addressing the nexus between self-compassion and SMA. This study contributes to the literature by confirming the influence of both positive and negative self-compassion on SMA.

2.3. Gratitude mediates the relationship of self-compassion to social media

Gratitude is characterized as a pervasive inclination to acknowledge and respond with gratitude to the benevolence of others that contributes to one’s positive experiences and outcomes.[37] Research indicates a strong correlation between gratitude and various positive psychological attributes, including positive emotions, life satisfaction, vitality, and optimism.[37] Moreover, there is a significant positive relationship between self-compassion and dispositional gratitude.[38,39] Adolescents undergoing self-compassion interventions have demonstrated a marked increase in expressions of gratitude.[40] Grateful individuals are more likely to view life as meaningful, comprehensible, and manageable,[41] exhibit less propensity to engage in prolonged social media use, and consequently, have a lower risk of developing SMA. This study explores the hypothesis that gratitude may serve as a mediating factor linking self-compassion to SMA.

From the standpoint of the interplay between positive self-compassion and gratitude, the theory of emotional experience by Lazarus and Lazarus[28] posits that a clear recognition of a benefactor’s role is crucial in eliciting feelings of gratitude. Individuals endowed with high levels of positive self-compassion are adept at accurately identifying and managing their emotions in challenging situations.[31] Consequently, those with heightened positive self-compassion are more inclined to experience and acknowledge gratitude in response to acts of kindness. Supporting this notion, research by Rao and Kemper[42] demonstrates that participants who underwent training in positive self-compassion reported significantly increased levels of gratitude.

From the angle of how negative self-compassion impacts gratitude, it is posited to have a detrimental effect. The impaired disengagement hypothesis suggests that individuals under psychological stress tend to fixate on the negative facets of events, impairing their ability to perceive and feel positive emotions.[43] Consequently, negative self-compassion may direct an individual’s cognitive focus toward negative stimuli, hindering the appreciation of gratitude when receiving assistance from others.[31] Research has substantiated that negative self-compassion is a predictor of lower levels of gratitude.[44]

Gratitude, as a positive emotional trait, can potentially mitigate the factors contributing to SMA. Drawing from the broaden-and-build theory of positive psychology,[45] positive emotions are known to expand an individual’s attention, cognition, and range of behaviors, building lasting personal resources for handling future challenges.[46] Hence, individuals who cultivate gratitude possess a wealth of internal resources that enhance their thought processes and actions, steering them away from isolated social media engagement and reducing their risk of SMA. Research supports that gratitude, as a personality characteristic, fosters better adaptation in individuals and diminishes addictive behaviors[47] – acting as a vital asset in aiding recovery toward a healthier state for those grappling with addiction.[48] Furthermore, gratitude has been identified as a negative predictor of Internet addiction,[49] suggesting that individuals with high levels of gratitude are more adept at avoiding the pitfalls of addiction when navigating the internet. Gratitude fulfills the basic psychological needs of adolescents, thereby decreasing the likelihood of Internet addiction.[50] In a study focused on left-behind children, gratitude was shown to directly curb pathological Internet gaming.[51] Therefore, in the context of college students, gratitude is intricately linked to SMA and can serve as an effective means for preventing and managing SMA.[52] This study aims to explore the mediating role of gratitude in the relationship between self-compassion and SMA through a mediation model.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Participants and procedures

During the peak period of COVID-19 in the country, we conducted a convenience-based questionnaire survey, targeting college students from 3 universities as our participants. These students volunteered to partake in the survey. The universities, all located in Hubei province – a central region of China – include a public key university specializing in finance and economics, a public undergraduate institution focused on science and technology, and a private vocational college with an emphasis on the arts. This selection represents a diverse cross-section of college student demographics. The questionnaire was designed with careful consideration for authority relevance and the number of questions posed. After discarding responses that were either too brief or patterned, the final sample comprised 1131 university students (519 males [45.9%] and 612 females [54.1%]), with an average age of 19.33 years (SD = 1.28). Participants were presented with an informed consent form before the survey commenced, and their willingness to respond served as their consent to participate. The survey received ethical approval from the Biomedical Ethics Committee of the lead author’s university, under Approval No. BME-2023-1-03.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Self-compassion scale

In this study, we utilized the Chinese version of the Self-Compassion Scale developed by Chen et al,[53] based on the original scale introduced by Neff.[32] The scale comprises 25 items, structured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These items are organized into 6 dimensions: self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification. The first 3 dimensions are categorized as positive self-compassion, while the latter 3 are indicative of negative self-compassion. By reverse scoring the applicable items and calculating the average score across all items, we determined the level of positive or negative self-compassion, where a higher score reflects stronger self-compassion. The reliability of the scale was confirmed in our study, with an overall Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.849 and subscale coefficients for positive and negative self-compassion both at 0.912.

3.2.2. Gratitude questionnaire

For measuring gratitude, our study employed the Chinese version of the Gratitude Questionnaire, as adapted by Zhou and Wu[54] from the original scale developed by McCullough et al.[37] This questionnaire includes 6 items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). We applied reverse scoring to applicable items before calculating the average score across all items, with higher scores indicating a greater propensity for gratitude. The reliability of the gratitude questionnaire in our study was affirmed by a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.827.

3.2.3. Bergen social media addiction scale

In this study, we utilized the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale, as developed by Andreassen et al.[18] This scale comprises 18 items, organized into 6 dimensions: salience, tolerance, mood modification, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse,[55,56] with responses captured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of SMA. The reliability of the scale was excellent in our study, as demonstrated by an internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach alpha) of 0.945.

3.2.4. Data analysis strategy

Data analysis was conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 22.0 and IBM® SPSS® Amos™ version 23. We calculated descriptive statistics, including means (M) and standard deviations (SD), and performed Pearson correlation analyses with SPSS to assess the relationships among the variables. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted in AMOS to evaluate the construct validity of each scale used in the study. We also carried out a sequential mediation analysis employing the PROCESS macro (Model 4) in SPSS, adhering to recommended guidelines for testing mediation effects.[57] Mediation effects were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) did not contain zero.[58]

3.2.5. Common method variance test

We employed the Harman single-factor test to assess the presence of common method variance. The analysis revealed that 8 factors had eigenvalues greater than one, with the first-factor accounting for only 26.469% of the total variance (16.139% after rotation). This percentage falls below the critical threshold of 40%, suggesting that our study’s data were not significantly affected by common method bias.

4. Results

4.1. Correlational analysis of self-compassion, gratitude, and SMA

To minimize the impact of confounding variables, age, and sex were factored into the Pearson correlation analysis and controlled for in the subsequent models. The correlations among these variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation analysis of each variable.

| M | SD | Sex | Age | Positive self-compassion | Negative self-compassion | Gratitude | SMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | – | – | 1 | |||||

| Age | 19.33 | 1.28 | 0.074* | 1 | ||||

| Positive self-compassion | 3.88 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.240** | 1 | |||

| Negative self-compassion | 2.64 | 0.88 | −0.124** | −0.217** | −0.508** | 1 | ||

| Gratitude | 4.37 | 1.04 | −0.05 | 0.110** | 0.545** | −0.450** | 1 | |

| SMA | 2.14 | 0.84 | −0.097** | −0.252** | −0.575** | 0.635** | −0.424** | 1 |

SMA = social media addiction.

0 = female, 1 = male.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Table 1 indicates that sex had a significant negative correlation with both negative self-compassion and SMA scores. Age showed a significant positive correlation with positive self-compassion and gratitude, yet it was significantly negatively correlated with negative self-compassion and SMA. Positive self-compassion exhibited a significant positive correlation with gratitude and a significant negative correlation with negative self-compassion and SMA. Conversely, negative self-compassion had a significant negative correlation with gratitude and a significant positive correlation with SMA. Additionally, gratitude was significantly negatively correlated with SMA.

4.2. The mediating role of gratitude between self-compassion and SMA

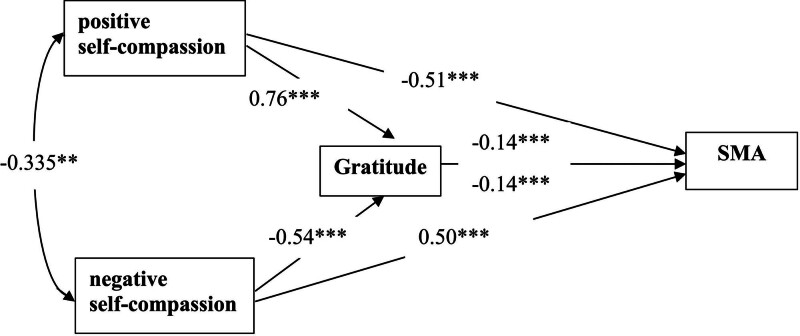

In the PROCESS analysis, sex and age were controlled to assess the mediation effects.[57] Positive self-compassion was found to significantly predict gratitude positively (β = 0.76, P < .001), and in the context of positive self-compassion, gratitude significantly negatively predicted SMA (β = −0.16, P < .001). Positive self-compassion also showed a significant negative predictive effect on SMA directly (β = −0.50, P < .001). Conversely, negative self-compassion significantly negatively predicted gratitude (β = −0.55, P < .001), and in scenarios of negative self-compassion, gratitude significantly negatively predicted SMA (β = −0.13, P < .001). Furthermore, negative self-compassion had a significant positive predictive effect on SMA (β = 0.60, P < .001). The results are detailed in Tables 2,3 and 4.

Table 2.

Regression analysis of the relationship of variables in the model.

| Regression equation | Fit index | Regression coefficient significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | R | R 2 | F | β | t |

| Gratitude | Constant | 0.55 | 0.30 | 161.18 | 1.76 | 4.42*** |

| Sex | −0.11 | −2.11* | ||||

| Age | −0.02 | −0.72 | ||||

| Positive self-compassion | 0.76 | 21.44*** | ||||

| SMA | Constant | 0.61 | 0.37 | 165.85 | 6.27 | 20.51*** |

| Sex | −0.15 | −3.73*** | ||||

| Age | −0.08 | −4.85*** | ||||

| Gratitude | −0.14 | −5.95*** | ||||

| Positive self-compassion | −0.51 | −15.70*** | ||||

SMA = social media addiction.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Regression analysis of the relationship of variables in the model.

| Regression equation | Fit index | Regression coefficient significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | R | R 2 | F | β | t |

| Gratitude | Constant | 0.46 | 0.21 | 101.81 | 5.62 | 12.34*** |

| Sex | −0.22 | −3.87*** | ||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.66 | ||||

| Negative self-compassion | −0.54 | −16.85*** | ||||

| SMA | Constant | 0.66 | 0.44 | 222.13 | 2.95 | 8.97*** |

| Sex | −0.05 | −1.39 | ||||

| Age | −0.08 | −5.11*** | ||||

| Gratitude | −0.14 | −7.01*** | ||||

| Negative self-compassion | 0.50 | 20.47*** | ||||

SMA = social media addiction.

P < 0.001.

Table 4.

Bootstrap analysis for significance test of mediating effects.

| Effect estimates | Bootstrap standard error | Bootstrap CI lower bound | Bootstrap CI upper bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive self-compassion → SMA (total effect) | −0.61 | 0.03 | −0.66 | −0.55 |

| Positive self-compassion → SMA (direct effect) | −0.51 | 0.03 | −0.57 | −0.44 |

| Positive self-compassion → Gratitude → SMA | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.07 |

| Negative self-compassion → SMA (total effect) | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.62 |

| Negative self-compassion → SMA (direct effect) | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Negative self-compassion → Gratitude → SMA (indirect effect) | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

SMA = social media addiction.

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method validated the mediation effects. For positive self-compassion, the 95% CI for the direct effect did not include zero, confirming the significant direct effect of positive self-compassion on SMA. The mediation path through gratitude also had a 95% CI not including zero, indicating that gratitude mediates the relationship between positive self-compassion and SMA. Similarly, for negative self-compassion, the 95% CI of the direct effect excluded zero, underscoring the significant direct impact of negative self-compassion on SMA. The mediation path via gratitude also excluded zero, demonstrating that gratitude serves as a mediator between negative self-compassion and SMA. Figure 1 illustrates the specific path model.

Figure 1.

The mediating role of gratitude between self-compassion and SMA. **P < .01,***P < .001. SMA = social media addiction.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of the relationships between variables

This research revealed that with age, college students tend to exhibit higher levels of positive self-compassion and gratitude. Conversely, younger students displayed greater tendencies toward negative self-compassion and SMA. Notably, elevated positive self-compassion was linked to increased gratitude, alongside reduced negative self-compassion and SMA. On the other hand, heightened negative self-compassion correlated with increased SMA and diminished gratitude levels. Furthermore, students with more pronounced gratitude exhibited lower SMA scores (Table 4).

5.2. The role of positive self-compassion and negative self-compassion for SMA

Drawing on the findings of Su et al,[59] Griffiths et al,[60] and Monacis et al[17] which link sex and age to SMA, this study incorporated these variables as controls in our PROCESS analysis. After adjusting for sex and age, the influences of positive and negative self-compassion on SMA became more pronounced. Our analysis demonstrated that positive self-compassion significantly lowers SMA levels in college students, while negative self-compassion directly and positively influences SMA; in other words, a lack of self-compassion can exacerbate SMA levels, corroborating prior research findings.[27] Positive self-compassion, embodying self-kindness, empowers students to perceive life more objectively and calmly, steering clear of dwelling on negative cues.[44] This mindfulness promotes reduced anxiety and depression[32] and, by encouraging a realistic engagement with life’s challenges, naturally diminishes social media usage, thereby lowering SMA levels.

In contrast, students who exhibit negative self-compassion tend to amplify feelings of helplessness and frustration in their lives, lingering over negative emotions, sidestepping real-life issues and social interactions, gravitating toward internet addiction, and consequently increasing their social media engagement, which worsens SMA symptoms. This study underscores the critical role of fostering positive self-compassion among college students to combat self-critical tendencies and manage emotions more rationally and calmly.[29] Doing so not only enhances their sense of connectedness with others but also diminishes their reliance on the internet and SMA. Thus, promoting positive self-compassion and reducing negative self-compassion are key strategies for mitigating SMA behaviors in college students.

5.3. The mediating role of gratitude

Delving deeper into the mechanisms through which self-compassion influences SMA, our analysis revealed that positive self-compassion exerts a protective effect against SMA via gratitude. This finding suggests that higher levels of positive self-compassion in college students are associated with increased experiences of gratitude, which in turn, correspond to lower levels of SMA. Drawing on gratitude theory[28] and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions,[61] students with positive self-compassion are more adept at objectively and fairly interpreting life events, responding to situations with rationality and calm, and cultivating a sense of gratitude.

Gratitude serves to broaden individuals’ cognitive and behavioral repertoires, mitigate negative cognitions, and curb maladaptive behaviors. This enables students to actively engage with real-life challenges, focus on release and letting go, and subsequently reduce their engagement with social media, thereby diminishing SMA levels. Conversely, our study also discovered that negative self-compassion could indirectly increase SMA levels by dampening gratitude. As posited by the impaired separation hypothesis,[43] the tendency of students to dwell on discomfort and their inability to shift focus away from negative events hinder the experience of positive emotions.[62] Students prone to negative self-compassion intensify their negative emotional states and focus on personal distress, fostering a sense of disconnection and experiencing less gratitude. Such students, burdened by negative emotions, engage more in negative behaviors, withdraw from social interactions, feel lonelier, spend excessive time on social media, and exacerbate their SMA.

Our findings underscore gratitude’s mediating role between self-compassion and SMA in college students. However, research indicates that gratitude levels tend to be lower during adolescence due to limited life experiences.[63] Implementing practices such as maintaining gratitude journals[64] can enhance students’ capacity to recognize and appreciate positive emotions. Likewise, bolstering gratitude education and awareness among college students encourages them to concentrate on their current studies and cherish their lives, thus contributing to a reduction in SMA.

While previous studies have separately explored the relationships between self-compassion and gratitude, self-compassion and SMA, as well as gratitude and SMA, the literature lacks an investigation into the interconnectedness among these 3 elements. Our study, aligning with the I-PACE model, incorporates an understanding of neurobiological factors and personal predispositions – including personality and psychobiological conditions – to anticipate the emergence of maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as the excessive use of social media for emotional regulation, leading to a heightened craving for frequent social media interaction. Innovatively, this research examines the mediating relationships among these variables, elucidates the impact of self-compassion on SMA in college students from a holistic perspective, explores gratitude’s role within this dynamic, and constructs a comprehensive model that integrates personal traits, emotional states, and addictive behaviors. This approach offers fresh insights into the phenomenon of SMA among college students.

6. Limitations

This study is subject to a few limitations. First, our research population was limited to college students. To develop a more comprehensive structural model, future research should extend these findings to diverse student demographics. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not permit inference of causality among the examined variables. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore the enduring effects of self-compassion on SMA in college students more deeply. Lastly, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces a degree of subjectivity. Future research efforts should aim to incorporate data from a variety of sources to enhance the reliability of findings.

7. Implications

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study offer valuable insights and suggest practical interventions for addressing SMA in college students. Considering the wide range of challenges faced by students addicted to social media – including difficulties in daily life, academic performance, family relationships, and emotional well-being – mental health professionals are encouraged to develop preventative and intervention strategies for SMA. First, clinical interventions could include programs aimed at enhancing self-compassion among college students, such as mindfulness and self-compassion practices. These programs can facilitate a shift from negative to positive self-compassion, thereby potentially reducing SMA levels. Second, targeted training to foster the recognition and appreciation of positive emotions can further guide students toward greater gratitude and lower SMA levels. Third, promoting healthy and moderate use of social media as a tool to improve academic and communicative competencies is advised. Lastly, the development of addiction control applications that alert users when they exceed predetermined usage thresholds and suggest constructive alternatives could serve as an effective preventive measure. We also hope our findings will aid educational institutions in crafting self-compassion development programs tailored to college students.

8. Conclusion

This research enriches the body of knowledge on SMA by examining how self-compassion, through its positive and negative dimensions, and mediated by gratitude, affects SMA. We have presented an integrated model that encompasses personal traits, emotional experiences, and addictive behaviors, offering a novel lens through which to view SMA in college students. The study demonstrates that positive self-compassion can significantly reduce SMA levels, whereas negative self-compassion tends to increase them. Gratitude was found to play a mediating role in this relationship, where positive self-compassion fosters SMA reduction through enhanced gratitude, and negative self-compassion exacerbates SMA by diminishing gratitude levels.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the hard and dedicated work of all the staff who implemented the intervention and evaluation components of the study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Pengcheng Wei.

Data curation: Pengcheng Wei.

Funding acquisition: Pengcheng Wei.

Writing – original draft: Pengcheng Wei.

Writing – review & editing: Pengcheng Wei.

Abbreviations:

- CIs

- confidence intervals

- QR

- quick response

- SMA

- social media addiction

- STAR

- specific situation, task, action, and result.

This study was supported by the Special Task Program for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20JDSZ3164).

Consent for publication is not applicable to this study.

An informed consent form was provided prior to the survey, and students’ willingness to answer the questions indicated their confirmation of participation. The consent form was approved by the Survey Research Ethics Committee of the Wuhan Polytechnic University.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Wei P. The effect of self-compassion on social media addiction among college students – The mediating role of gratitude: An observational study. Medicine 2024;103:21(e37775).

References

- [1].DataReportal. Digital 2021 October Global Statshot Report. 2021. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-october-global-statshot. Accessed April 23, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Heffer T, Good M, Daly O, MacDonell E, Willoughby T. The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: an empirical reply to Twenge et al. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7:462–70. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhong B, Huang Y, Liu Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;114:106524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ya-li Z, Yu-meng C, Juan-juan J, Guo-liang Y. The relationship between fear of missing out and social media addiction: a cross-lagged analysis. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang Y, Li S, Yu G. The relationship between social media use and fear of missing out: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychol Sin. 2021;53:273–90. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Griffiths MD. A “components” model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Substance Use. 2005;10:191–7. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110:501–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brown R. Some contributions of the study of gambling to the study of other addictions. Gambl Behav Problem Gambl. 1993;1:241–72. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Griffiths M, Kuss D. Adolescent social media addiction (revisited). Educ Health. 2017;35:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sun Y, Zhang Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict Behav. 2021;114:106699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Anderson EL, Steen E, Stavropoulos V. Internet use and problematic internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2017;22:430–54. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gorwa R, Guilbeault D. Unpacking the social media bot: a typology to guide research and policy. Policy Internet. 2020;12:225–48. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Deon T, Vasileios S, Rapson G, Jo D. Social media use and abuse: different profiles of users and their associations with addictive behaviours. Addict Behav Rep. 2023;17:100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ho TTQ. Facebook addiction and depression: loneliness as a moderator and poor sleep quality as a mediator. Telemat Inform. 2021;61:101617. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ali F, Ali A, Iqbal A, Ullah Zafar A. How socially anxious people become compulsive social media users: the role of fear of negative evaluation and rejection. Telemat Inform. 2021;63:101658. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Monacis L, Griffiths M, Limone P, Sinatra M, Servidio R. Selfitis behavior: assessing the Italian version of the selfitis behavior scale and its mediating role in the relationship of dark traits with social media addiction. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Monacis L, De Palo V, Griffiths MD, Sinatra M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:178–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017;64:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lin C, Lin C, Imani V, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. Evaluation of the selfitis behavior scale across two Persian-speaking countries, Iran and Afghanistan: advanced psychometric testing in a large-scale sample. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2020;18:222–35. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dalvi-Esfahani M, Niknafs A, Alaedini Z, Barati Ahmadabadi H, Kuss DJ, Ramayah T. Social media addiction and empathy: moderating impact of personality traits among high school students. Telemat Inform. 2021;57:101516. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Elena S, Griffiths M. Social media addiction profiles and their antecedents using latent profile analysis: the contribution of social anxiety, gender, and age. Telemat Inform. 2022;74:101879. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Monacis L, Griffiths MD, Limone P, Sinatra M. The risk of social media addiction between the ideal/false and true self: testing a path model through the tripartite person-centered perspective of authenticity. Telemat Inform. 2021;65:101709. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Duradoni M, Innocenti F, Guazzini A. Well-being and social media: a systematic review of Bergen addiction scales. Future Internet. 2020;12:24. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Worsley JD, Mansfield R, Corcoran R. Attachment anxiety and problematic social media use: the mediating role of well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21:563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brand M, Young K, Laier C, Wolfling K, Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: an interaction of person–affect–cognition–execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:252–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang SY, Xu Y. The attentional bias of individuals with different levels of search for and presence of meaning in life. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2007;22:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Iskender M, Akin A. Self-compassion and internet addiction. Turkish Online J Educ Technol. 2011;10:215–21. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lazarus RS, Lazarus BN. Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Neff K. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2:85–101. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. J Res Pers. 2007;41:908–16. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liu A, Wang W, Wu X. The influence of adolescents, self-compassion on posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth: the mediating role of gratitude. Psychol Dev Educ. 2022;38:859–68. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–50. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Selby EA, Franklin J, Carson-Wong A, Rizvi SL. Emotional cascades and self-injury: investigating instability of rumination and negative emotion. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:1213–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Heath NL, Joly M, Carsley D. Coping self-efficacy and mindfulness in non-suicidal self-injury. Mindfulness. 2016;7:1132–41. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Joeng JR, Turner SL. Mediators between self-criticism and depression: fear of compassion, self-compassion, and importance to others. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62:453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rogers ML, Kelliher-Rabon J, Hagan CR, Hirsch JK, Joiner TE. Negative emotions in veterans relate to suicide risk through feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82:112–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Breen WE, Kashdan TB, Lenser ML, Fincham FD. Gratitude and forgiveness: convergence and divergence on self-report and informant ratings. Pers Individ Diff. 2010;49:932–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Neff KD, Long P, Knox MC, et al. The forest and the trees: examining the association of self compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning. Self Identity. 2018;17:627–45. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bluth K, Eisenlohr-Moul TA. Response to a mindful self-compassion intervention in teens: a within-person association of mindfulness, self-compassion, and emotional well-being outcomes. J Adolesc. 2017;57:108–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF, Dean LR. More gratitude, less materialism: the mediating role of life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol. 2009;4:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rao N, Kemper K. Online training in specific meditation practices improves gratitude, well-being, self-compassion, and confidence in providing compassionate care among health professionals. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;22:237–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Koster EH, De Lissnyder E, Derakshan N, De Raedt R. Understanding depressive rumination from a cognitive science perspective: the impaired disengagement hypothesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu A, Wang W, Wu X. Understanding the relation between self-compassion and suicide risk among adolescents in a post-disaster context: mediating roles of gratitude and posttraumatic stress disorder. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56:218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol. 2000;55:647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Krentzman AR. Gratitude, abstinence, and alcohol use disorders: report of a preliminary finding. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;78:30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen G. Does gratitude promote recovery from substance misuse? Addict Res Theor. 2017;25:121–8. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mei S, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of core self-evaluation and gratitude on college students’ Internet addiction. China Higher Med Educ. 2017;3:44–5. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu C, Zhang W, Zeng Y, Ye T, Hu J, Li D. Gratitude, basic psychological needs, and problematic internet use in adolescence. Psychol Dev Educ. 2012;01:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wei C, Yu C, Ma N, Wu T, Li Z, Zhang W. The relationship between gratitude and pathological online game use among left-behind children: the mediating role of school affiliation. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2016;24:134–8. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cao R, Mei S, Liang L, Li C, Zhang Y. Relationship between gratitude and Internet addiction among college students: the mediating role of core self-evaluation and meaning in life. Psychol Dev Educ. 2023;39:286–94. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen J, Yan L, Zhou L. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of self-compassion scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;19:734–6. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhou X, Wu X. Understanding the roles of gratitude and growth adolescents after Ya’an earthquake: a longitudinal study. Pers Individ Diff. 2016;101:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hou Y, Xiong D, Jiang T, Song L, Wang Q. Social media addiction: its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology. 2019;13:article 4. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Liu Y. The Influence of Family Function on Social Media Addiction in Adolescents: The Chain Mediation Effect of Social Anxiety and Resilience. Hunan Normal University, Changsha; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wen Z, Chang L, Hau K, Liu H. Testing and application of the mediating effects. Acta Psychol Sin. 2004;36:614–20. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hayes A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Su W, Han X, Yu H, Wu Y, Potenza MN. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;113:106480. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Griffiths M, Kuss D, Demetrovics Z. Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In: Rosenberg K, Feder L, eds. Behavioral Addictions: Criteria, Evidence and Treatment. New York: Elsevier; 2014:119–41. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1367–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Watkins E, Brown RG. Rumination and executive function in depression: an experimental study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:400–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Froh JJ, Fan J, Emmons RA, Bono G, Huebner ES, Watkins P. Measuring gratitude in youth: assessing the psychometric properties of adult Gratitude Scales in children and adolescents. Psychol Assess. 2011;23:311–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:377–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]