External inputs to health needs assessment and the prioritisation of health services may be seen as one means of addressing the “democratic deficit” in the NHS. Such external inputs can be discussed on three levels. The first concerns the formal governance arrangements of the service and encompasses questions about electing health authority members and transferring the NHS purchasing function to local government authorities1,2; it is not discussed further here. The second level of input may be characterised by arrangements for consultation with the general public, whether or not they happen to be current patients or users. The third level concerns the consultation of current users about needs and priorities. The importance of these two levels was recently recognised in a new white paper.3

Summary points

Although health authorities have increased local consultation, its quality remains dubious, with greatest emphasis on one-off consultation exercises

Information gained through public consultation may either be marginalised or incorporated according to professional priorities

It is important to acknowledge limitations to professional knowledge as well as to respond to inequalities in health; through citizens’ juries, user consultation panels, focus groups, questionnaire surveys, and opinion surveys, local knowledge can be used to effect such a response

There is scope for greater local involvement in decision making

Changes to the organisation and funding of primary care are vital if effective involvement is to be sustained

Consultation of the public

The nature and extent of public involvement in determining health needs has increased, but the quality of consultation remains questionable.4,5 Some health authorities have established ongoing consultation procedures, including citizens’ juries, large scale postal panels, and smaller face to face panels, but most consultation has consisted of one-off surveys of the public or consultation with local user groups. Most authorities have no provisions for ongoing means of consultation.4

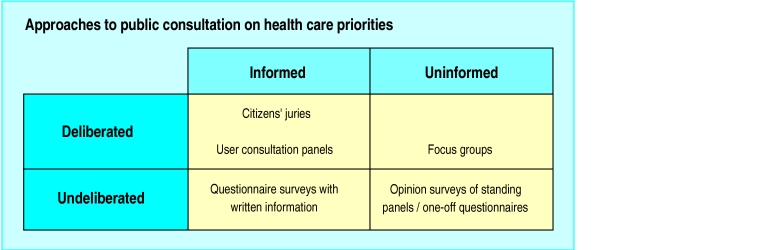

These approaches may be classified according to two simple dimensions.4 One dimension relates to whether respondents to the consultation exercise were provided with any information, and the second relates to whether respondents were able to engage in any discussion or deliberation in arriving at their views. These dimensions define the matrix shown in the box.

Citizens’ juries and similar panels of members of the public place respondents in the situation where they are informed about the issues and choices at stake and must deliberate with others to arrive at a recommendation.6,7 Such mechanisms attempt to collect the views of the public not necessarily as they are, but as they might be if information and the opportunity for discussion are available. Diametrically opposed is an approach that seeks to consult the public as it is, usually on the basis of statistically representative sampling. Such opinion surveys collect data from a generally uninformed public and do not encourage deliberation. The other two cells in the matrix are hybrids: focus groups encourage discussion of uninformed opinion, and in a few cases attempts have been made to provide a written briefing to survey respondents.

Either construction of the public—as uninformed and undeliberating, or as informed and deliberating—is open to objection, and of course any such objection can be used by NHS “insiders” as a pretext for ignoring or overriding the outcomes of consultation.The organisers of consultation exercises can help to produce the outcomes that they prefer by their choice of questions, though this can be avoided through involving the public in the formulation of the inquiry.

Some studies have found that participants on juries and panels have been satisfied with their experience and think that ordinary people can participate effectively in such exercises.8 Other research has found that respondents to opinion surveys are reluctant to accept a public role in determining priorities for health care.9 This suggests that mechanisms with informed and deliberated components may enhance participation when the aim is to produce substantive recommendations.

Responding to user groups

When health authorities have opted to involve existing user groups, it is because they have been influenced by legislative change and occasionally by strong personal commitment to user led services and have accepted the groups as legitimate stakeholders in healthcare decision making.10 Often, a strong feature of this recognition is officials’ need for better information about existing services and about needs and priorities identified by the groups. When it is recognised that managers and professionals do not necessarily know best, user groups are seen as excellent conduits of information.

Even so, officials can be quick to qualify and circumscribe the influence of user groups, typically through questioning their “representativeness.” This ambivalence is part of a more encompassing approach in which officials are able to undermine the legitimacy of groups, should the perceived need arise,1 while at the same time using the user groups’ views in their own negotiations with other officials.11

Local consultation in primary care

Attention has been most keenly focused on the need and opportunity for local consultation within health authorities,12 so it is no surprise that most initiatives have occurred at this level. Relatively little attention has been paid to local consultation specifically in primary care.13 The increasing role of primary care in purchasing, and most likely in future locality based commissioning of health services, makes it necessary to determine and respond to specifically local needs.12,14

These developments set up the appropriateness of local health needs assessment as a basis of purchasing and commissioning, but they do not in themselves require local participation in such assessment. Many of the ways of assessing the health needs of a local population do not entail going anywhere near the population itself.15 The remainder of this section therefore discusses why primary care practitioners should involve the local community in decision making about healthcare provisioning, and importantly, considers the obstacles to such participation.

Two related issues bring into question the assumption that general practitioners are in a position to act as proxies for patients’ health needs16: firstly, the evidence on differing perceptions of doctors and patients,17,18 and secondly, the disparity between demand and needs.19,20 Taken together, these highlight the danger of basing knowledge about the distribution of health (need) in a community solely on experience of general practice. Many health professionals, including general practitioners, see the proactive seeking out of need as secondary to a primary care responsibility for individual demand, and they see knowledge held by people living locally as “inferior” to that generated by clinical observation and diagnosis.21,22 Most illnesses, though, do not lead to a medical consultation,23 so professional knowledge cannot be assumed to reflect the experience of individual patients, and presentation at surgery may best be understood as one expression of demand. One way of filling gaps in understanding is to consult the local community.

Providing for equity

The issue of equity in health (provision) also makes it incumbent to move beyond a model of primary care that is based on professional response to demand—to a model that recognises the importance of responding to need that is otherwise unidentified. There is increasing evidence that the distribution and degree of inequality in economic welfare has a direct impact on health.24 Local participation in healthcare decision making can run the danger of increasing this inequality by allowing the members of the public who are most able to register their demands or needs to do so at the expense of the less articulate25; nevertheless, if participation is handled appropriately, previously marginalised groups can be provided with a voice and can be involved in decision making.26

Methods of public consultation

Citizens’ juries—Participants are selected as representatives of public or local opinion. Juries sit for a specified length of time, during which they are presented with information to help in decision making. Typically, experts give evidence and jurors have an opportunity to ask questions or debate relevant issues6

User consultation panels—Consist of local people selected as representative of the locality or population. Typically, members are rotated to ensure that a broad range of views is heard. Topics for consideration are decided in advance and members are presented with relevant information to encourage informed discussion. Meetings are often facilitated by a moderator7

Focus groups—Typically, semistructured discussion groups of 6-8 participants led by a moderator, with focus on specific topics. Debate and discussion are encouraged

Questionnaire surveys—Can be postal or distributed (in the surgery, for example). This structured or systematic means of data collection allows information to be collected from a large sample of respondents and the relation between variables to be examined. Most appropriate when the issues relevant to the topic being investigated are already known in some detail

Opinion surveys of standing panels—Standing panels are large, sociologically representative samples (typically 1000 or more) of a the population in a health authority; they are surveyed at intervals on matters of concern to the authority. There is usually a replacement policy aimed at ensuring that individuals do not serve on the panel indefinitely

Current potential for consultation in primary care

What scope exists for local consultation under current healthcare policy and organisation? As already mentioned, problems arise from the fact that not only is primary health care essentially demand driven but this demand is arbitrarily divided into practice specific populations which often do not correspond to naturally occurring geographical localities and populations.13 Professional and official thinking therefore needs to acknowledge in both the organisation and funding of primary care the appropriateness of responding to the needs of the local (as distinct from the practice) population.27

The poor understanding and limited uptake of local consultation within primary care21,28 arises partly from the absence of relevant training—which makes an inherently challenging activity even more difficult. Working with groups representing different community interests demands considerable skills and flexibility, and health professionals are currently poorly prepared for this.26 Local people may not be used to having their opinions invited, let alone being asked to take a more active role.29 One-off consultation initiatives are thus likely to have limited benefit, and they may work against longer term effectiveness, which depends on proper structures and mechanisms for sustained, meaningful communication and action.

There is already considerable scope for community based health needs assessment within primary care. Members of the wider primary healthcare team are already in touch with local networks, including resident’s associations, mother and toddler groups, schools, and other voluntary organisations.30 Community nurses have been producing community profiles, which could be used to develop stronger links with the community.13 The spread of appropriate knowledge and skills and the practical need to divide any workload makes it vital to involve the whole primary care team, and such involvement is in line with the underlying general ethos of full participation in healthcare decision making.31

Reconciling conflicting needs

One overriding issue remains. Comprehensive health needs assessment is likely to produce different, potentially conflicting needs.15,32 How are these different priorities, views, and opinions to be weighed against one another in order to avoid a position of stalemate and to effect positive change? Available suggestions may differ, but academic contributors and decision makers alike are acutely aware of resource limitations and their implications for meeting the full range of need identified through any health needs assessment process.32,33 There are no easy answers, but with regard to local involvement at least it is clear that people must be involved in identifying need and also in prioritising and responding to these needs.26

There is no doubt that the concept and practice of local participation in health needs assessment is particularly challenging. Although there are no models for how to go about it and there are a number of potential obstacles, there is already considerable potential for existing arrangements to be extended to incorporate local participation. While it has been argued24 that the recent policy obsession with needs assessment has been prompted by a desire to reduce public expenditure, this should not detract from the possibility of using needs assessment, particularly that with community involvement, as a means of not only promoting good health but reducing inequalities in its distribution.

Footnotes

These articles have been adapted from Health Needs Assessment in Practice, edited by John Wright, which will be published in July.

References

- 1.Harrison S. The rationing debate: central government should have a greater role in rationing decisions: the case against. BMJ. 1997;314:970–973. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7085.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter DJ, Harrison S. Democracy, accountability and consumerism. In: Iliffe S, Munro J, editors. Healthy choices: future options for the NHS. London: Lawrence and Wishart; 1997. pp. 120–154. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS: modern, dependable. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mort M, Harrison S, Dowswell T. Public health panels in the UK: influence at the margins? In: Khan UA, ed. Innovations in participation. London: Taylor and Francis (in press).

- 5.Pickard S, Williams G, Flynn R. Local voices in an internal market: the case of community health services. Social Policy and Administration. 1995;29:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenaghan J, New B, Mitchell E. Setting priorities: is there a role for citizens’ juries? BMJ. 1996;312:1591–1593. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7046.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowie C, Richardson A, Sykes W. Consulting the public about healthcare priorities. BMJ. 1995;311:1155–1158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowswell T, Harrison S, Lilford RJ, McHarg K. Health authorities use panels to gather public opinion. BMJ. 1995;311:1168–1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1168c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heginbotham C. Rationing. BMJ. 1992;304:1168–1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6825.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes M, Harrison S, Mort M, Shardlow P, Wistow G. Users, officials and citizens in health and social care. Local Government Policymaking. 1996;22:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mort M, Harrison S, Wistow G. The user card: picking through the organisational undergrowth in health and social care. Contemporary Politics. 1996;2:1133–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Management Executive. Local voices, the views of local people in purchasing for health. London: Department of Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peckham S. Local voices and primary health care. Critical Public Health. 1992;5(2):36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Executive. Developing NHS purchasing and GP fundholding. London: Department of Health; 1994. (EL(94)79.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillam SJ, Murray SA. Needs assessment in general practice. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1996. (Occasional paper 73.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health; Welsh Office. General practice in the National Health Service: a new contract. London: HMSO; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heritage Z. Community participation in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1994. (Occasional paper 64.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes M, Wistow G. Understanding user involvement. In: Barnes M, Wistow G, editors. Researching user involvement. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health Services Studies; 1992. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw JR. A taxonomy of social need. In: Mclachlan G, editor. Problems and progress in medical care. Oxford: Nuffield Provincial Hospital Trust; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens A, Gabbay J. Needs assessment, needs assessment ... Health Trends. 1991;23(1):20–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan J, Wright J, Wilkinson J, Williams R. Health needs assessment in primary care: a study of understanding and experience in three districts. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowling A, Jacobsen B, Southgate L. Health services priorities. Exploration in consultation of the public and health professionals on priority setting in an inner London health district. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:851–857. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90138-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Last JM. The iceberg: completing the clinical picture in general practice. Lancet. 1963;ii:28–31. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradshaw J. The conceptualisation and measurement of need. In: Popay J, Williams G, editors. Researching the people’s health. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Percy-Smith J, Sanderson I. Understanding local needs. London: Institute for Public Policy Research; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dockery G. Participatory research in health. London: Zed Books; 1996. Rhetoric or reality? Participatory research in the National Health Service. ; pp. 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruta DA, Duffy MC, Farquhaeson A, Young AM, Gilmour FB, McElduff SP. Determining the priorities for change in primary care: the value of practice-based needs assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:353–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard P. Community involvement in a changing world. In: Heritage Z, editor. Community participation in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1994. pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowswell T, Drinkwater C, Morley V. Developing an inner city health resource centre. In: Heritage Z, editor. Community participation in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1994. pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Findlay G, Palmer J. Reorientating health promotion in primary care to participative approaches. In: Heritage Z, editor. Community participation in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1994. pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown I. The organisation of participation in general practice. In: Heritage Z, editor. Community participation in primary care. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1994. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson J, Elkan R. Health needs assessment: theory and practice. London: Churchill Linvingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.London Health Economics Consortium; SDC Consulting. Local health and the vocal community, a review of developing practice in community based health needs assessment. London: London Primary Health Care Forum; 1996. [Google Scholar]