Abstract

Greece is a highly endemic country for Leishmania species. Canine cases of leishmaniosis are recorded in different parts of the country. However, no case of feline leishmaniosis has been reported yet. In the present study, the seroprevalence in cats was investigated as a first approach to measuring Leishmania spp. infection of this animal species, in Greece. For this purpose, blood serum samples from 284 stray adult cats, living in the major area of Thessaloniki (Northern Greece), were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of anti-Leishmania spp. IgG. Eleven (3.87%) of the examined animals were found positive. The prevalence was lower in cats than in dogs coming from the same area, based on previous studies. Despite the low seroprevalence for Leishmania spp. in cats, leishmaniosis may be taken into consideration concerning the differential diagnosis of the feline diseases, especially in endemic areas.

Leishmania species are intracellular, protozoan organisms, transmitted by the bite of sandflies, causing leishmaniosis in human and animals. Feline leishmaniosis has been reported sporadically in various parts of the world.

Greece is highly endemic for Leishmania infantum. The disease is very common in dogs. However, no case of feline leishmaniosis has ever been reported. Despite the fact that antibodies against Leishmania spp. are commonly found in dogs in Greece, 1 there are not any data available for the presence of antibodies in cats. Cats may have a role as reservoir host of the parasite 2 and as they live close together with humans and dogs, this role should be defined. The aim of the present study was to investigate, for the first time, the prevalence of specific antibodies against L. infantum in cats in Greece and to configure an aspect of their epidemiological importance in human and canine leishmaniosis in the area.

The collection of the blood samples was performed during a project of vaccination and castration/spaying of stray cats in the city and the suburbs of Thessaloniki (Northern Greece). Blood samples were collected from 284 stray cats (175 females and 109 males) with no evident clinical signs of any disease. The sex of each animal and the neighbourhood where they originated from was recorded. All animals were adults (no exact estimation of age was possible), of local crossbreed.

A whole L. infantum antigen was used, prepared from a dog isolate, originated from the same area (Thessaloniki, Greece). The sera were examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), for the detection of specific IgG. ELISA conditions were determined by checkerboard titrations. The seroprevalence data were compared with Student's t-test and χ2 test using SPSS (Release 15.0 for Windows). Differences in seroprevalence were considered as significant when P≤0.05.

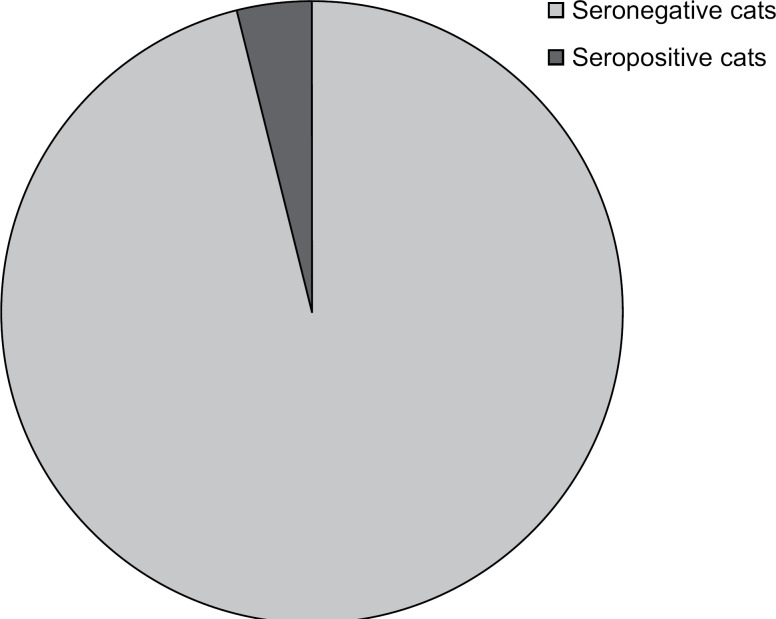

Eleven out of the 284 blood serum samples were found positive for anti-Leishmania spp. IgG (3.87%, Fig 1). The positive cats were six females and five males and the locations were they lived were randomly scattered in the sampling area. No significant difference between sex and area was noted (P>0.05).

Fig 1.

Seropositive (11/284) cats for anti-Leishmania spp. IgG in the Thessaloniki area.

The cat is a rare host of Leishmania spp. but lately, it is considered to play an active role, not clarified yet, in the epidemiology of this disease in the Mediterranean area.3,4 However, this animal species is believed to have a high degree of natural resistance, as observed following experimental infection, which is probably dependent on genetic factors, not strictly related to cell mediated immunity. 4

In Europe, feline leishmaniosis cases with cutaneous and/or visceral involvement have been described from Portugal, France, Spain and Italy.3,5,6 In the cases where typing of the aetiological agent was performed (isoenzymes, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) L. infantum was identified.5,7

When the seroprevalence in cats is compared to the one in the canine population of the same area, usually cats are found to be less seropositive. In reviews by Gradoni 8 and Pennisi 6 the results from several serological surveys in different countries are stated. In France the prevalence in cats reached 12.4% compared to the canine prevalence rates of 26.5%. In Brazil 10.7% of the cats were positive in ELISA while the seroprevalence in dogs was 40.3%. 9 Based on the data above, the ratio of feline to canine positive sera in Brazil is similar to the ratio found in the present study, ie, about 1:3.5. In Italy the prevalence is up to 68%, while in dogs the percentages reach 40%, depending on the area of the country. 2 In Spain, feline seroprevalence has been found up to 60%, 10 with the canine being up to 19.8%. In Portugal, in 4/23 cats a low level of antibodies was detected 11 and 20.4% of the dogs were found seropositive. 12

In the area of the present study, the prevalence of Leishmania spp. antibodies in dog is 21.3%, 13 much higher than the one determined here, in cats. This seems to correspond well with the reports that cats, in foci of leishmaniosis in southern Europe, are more refractory than dogs to the infection of L. infantum. 7 This is explained by the hypothesis that the immune response in cats, mainly cellular immunity, is effective enough to control the infection and confer a certain degree of natural resistance, if there are not immunosuppressive events such as feline leukaemia virus or feline immunodeficiency infection. 14

In a recent survey in Spain, 3% of the cats were found PCR positive. 15 In Portugal, Leishmania spp. DNA was detected in blood in 7/23 cats (30.4%) while a low level of antibodies was detected in only four serum samples. 11 Similarly, the rate of infection in dogs was considerably higher than previously described in seroepidemiological studies, when molecular techniques or cellular immunity tests were mobilised. In this study, we tested Leishmania spp. exposure in cats only by means of serology, so an underestimation of the actual rate of infection may be possible. Therefore, surveys using techniques such as PCR and cellular immunity tests should be performed in cats to estimate better any Leishmania spp. infection in the future.

The biggest question when valuating a seroprevalence in diseases such as leishmaniosis is what does a positive result mean in a clinical sense. As none of the positive cats were showing clinical signs, the possibilities are that they were either infected, remaining asymptomatic carriers up to the date of examination, or simply exposed to the organism by sandflies' bite and had killed off the promastigotes before an infection had developed. Whatever the case may be, the detection of antibodies in cats in Greece questions the possibility of the epidemiological role of this animal species in canine or human leishmaniosis in the country.

Despite the low seroprevalence, feline leishmaniosis is always a possibility, especially in endemic areas. As the clinical signs are unspecific and similar to those observed in other diseases commonly found in cats, leishmaniosis may be taken into consideration concerning the differential diagnosis and consequently, diagnostic tests (serology, cytology, PCR and others) should be performed in order to investigate the possibility of Leishmania spp. infection. 7

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thanks to Dr M. Grazia Pennisi (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Messina, Italy) for providing the cat control sera.

References

- 1.Papadopoulou C., Kostoula A., Dimitriou D., Panagiou A., Bobojianni C., Antoniades G. Human and canine leishmaniasis in asymptomatic and symptomatic population in Northwestern Greece, J Infection 50, 2005, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maroli M., Pennisi M.G., Di Muccio T., Khoury C., Gradoni L., Gramiccia M. Infection of sandflies by a cat naturally infected with Leishmania infantum, Vet Parasit 145, 2007, 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hervas J., De Lara F. Chacon-M, Sanchez-Isarria M.A., et al. Two cases of feline visceral and cutaneous leishmaniosis in Spain, J Feline Med Surg 1, 1999, 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancianti F. Feline leishmaniasis: what's the epidemiological role of the cat?, Parassitol 46, 2004, 203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozon C., Marty P., Pratlong F., et al. Disseminated feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum in Southern France, Vet Parasitol 75, 1998, 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennisi MG. A high prevalence of feline leishmaniasis in southern Italy. In: Canine Leishmaniasis: Moving Towards a Solution. Proceedings of the Second International Canine Leishmaniasis Forum, Sevilla, Spain, 2002: 39–48.

- 7.Poli A., Abramo F., Barsotti P., et al. Feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum in Italy, Vet Parasitol 106, 2002, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gradoni L. Epizootiology of canine leishmaniosis in southern Europe. In: Canine Leishmaniasis: An Update. Proceedings of the International Canine Leishmaniasis Forum, Barcelona, Spain, 1999: 32–39.

- 9.Dantas-Torres F., de Brito M.E., Brandão-Filho S.P. Seroepidemiological survey on canine leishmaniasis among dogs from an urban area of Brazil, Vet Parasitol 140, 2006, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martín-Sánchez J., Acedo C., Muñoz-Pérez M., Pesson B., Marchal O., Morillas-Márquez F. Infection by Leishmania infantum in cats: epidemiological study in Spain, Vet Parasit 145, 2007, 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maia C., Nunes M., Campino L. Importance of cats in zoonotic leishmaniasis in Portugal, Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2008, 8, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cardoso L., Rodrigues M., Santos H., et al. Sero-epidemiological study of canine Leishmania spp. infection in the municipality of Alijo (Alto Douro, Portugal), Vet Parasitol 121, 2004, 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diakou A. Epidemiological study of dog parasitosis diagnosed by blood and serological examinations, ANIMA 8, 2000, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solano-Gallego L., Rodríguez-Cortés A., Iniesta L., et al. Cross-sectional serosurvey of feline leishmaniasis in ecoregions around the Northwestern Mediterranean, Am J Trop Med Hyg 76, 2007, 676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabar M.D., Altet L., Francino O., Sánchez A., Ferrer L., Roura X. Vector-borne infections in cats: molecular study in Barcelona area (Spain), Vet Parasitol 151, 2008, 332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]