Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is caused by retrograde flow of gastric contents through an incompetent gastro-oesophageal junction. The disease encompasses a broad spectrum of clinical disorders from heartburn without oesophagitis to severe complications such as strictures, deep ulcers, and intestinal metaplasia (Barrett’s oesophagus).1 The prevalence of heartburn, the most typical symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, is extremely high,2 but most people with reflux do not seek medical help for this condition and treat themselves with over the counter preparations. Oesophagitis (defined by mucosal breaks) is less frequent, occurring in less than half of patients undergoing endoscopy for reflux symptoms. Symptoms and severity of oesophagitis are poorly correlated. Although reflux may remain silent in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, heartburn can severely affect the quality of life of patients with negative endoscopy results. The natural course of the disease also varies considerably.2 Patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease seen by gastroenterologists usually have a chronic condition with frequent relapses, whereas those who rely on general practitioners’ help usually have less severe disease, consisting of intermittent attacks with prolonged periods of remission.

Summary points

Most patients with dominant heartburn have no signs of oesophagitis at endoscopy. However, chronic relapsing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease can severely affect quality of life

In primary care many patients can be successfully treated by intermittent courses of drugs on demand

Alginate-antacids and H2 receptor antagonists are useful in patients with mild disease

Cisapride is as effective as H2 receptor antagonists in short term treatment and can prevent relapse in mild oesophagitis

Proton pump inhibitors relieve symptoms and heal oesophagitis more completely and faster than other drugs. They are effective throughout the disease spectrum, and maintenance therapy prevents recurrences

The principles of laparoscopic and open antireflux surgery are the same. In skilled hands, similarly good results have been reported up to two years after both approaches

In young fit patients laparoscopic surgery may be a cost effective alternative to a lifetime of drug treatment

Relief of symptoms and prevention of relapses are the primary aims of treatment for most patients. However, healing is also an important objective for those with moderate to severe oesophagitis or complications, or both. These goals can now be achieved, at least in part, for nearly all patients thanks to the recent development of effective drugs, especially proton pump inhibitors. The last decade has also seen the rapid development of laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

Several reviews on the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease have been published recently,3–6 and this information has been supplemented by a Medline search covering 1995-7. We also used a database created during a recent workshop (Genval, Belgium, October 1997). From the 429 references available in this database we selected those reporting trials comparing proton pump inhibitors with other drugs, treatment of patients with negative endoscopy results, meta-analysis of trials, evaluation of laparoscopic surgery, and cost-utility analysis.

Medical treatment

Lifestyle and dietary recommendations

Lifestyle and dietary recommendations, together with antacids, have long been the mainstay of treatment. The recommendations were based on physiological studies showing reduced acid exposure, at least in some instances.7 In fact, the effectiveness of these measures has not been established by well controlled trials. The role of obesity in the pathogenesis of the disease, as well as the benefit of weight loss, has not been proved. No benefit has been shown from giving up smoking or discontinuing the use of drugs such as bronchodilators in asthmatic subjects.8 Although it is wise to stop smoking or reduce the consumption of fatty foods for other reasons, not much benefit can be expected in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Raising the head of the bed9 and avoiding lying down within three hours after dinner may be useful, especially for patients with severe regurgitation or nocturnal symptoms. When specific foods or drugs are poorly tolerated by a patient it is logical to avoid or withdraw them.

Antacids and alginate-antacids

Though several placebo controlled trials have failed to establish their efficacy,10 epidemiological studies have shown that antacids and alginate-antacids are often used successfully as self treatment by people with reflux who do not seek medical help.11 The combination of antacids with alginate is more effective than antacids alone. In a large open trial of alginate-antacid taken on demand, most patients with mild oesophagitis remained in good clinical remission during the six months of the study.12

Prokinetics

Since gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is primarily a motility disorder the use of prokinetics has an excellent rationale. Bethanechol and the anti-dopaminergics metoclopramide and domperidone have proved slightly effective. However, their marginal benefit is often offset by poor tolerance. They have now been superseded by cisapride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT4) receptor agonist which enhances oesophageal peristaltic waves, increases oesophageal sphincter tone, and accelerates gastric emptying.13

In short term treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease cisapride (10 mg four times a day or 20 mg twice daily) has proved more effective than placebo and nearly as effective as H2 blockers in relieving symptoms and healing oesophagitis.13 Cisapride (10 mg twice daily or 20 mg at bedtime) also prevents relapses in patients with mild oesophagitis.14

Sucralfate

Sucralfate is a polysulphate sucrose salt which is supposed to protect oesophageal mucosa. Conflicting results have been reported in trials in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. It has little, if any, role in modern antireflux therapy.

Acid suppression

H2 receptor antagonists

H2 receptor antagonists (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and nizatidine) were the first acid suppressors shown to be effective in short term treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.15 However, the benefit was less than initially expected, especially in severe oesophagitis, for which the average gain in healing has not exceeded 10%. Moreover, maintenance therapy with standard doses of H2 blockers (for example, 150 mg ranitidine twice daily) does not prevent relapses.16 There are many reasons for the limited efficacy of these drugs, including tolerance (reduced efficacy over time17) and incomplete inhibition of postprandial gastric acid secretion.15,16 Increasing the dose18 and dosing frequency improves the efficacy, although it probably reduces compliance and increases cost. Combined treatment with prokinetics is less effective and more expensive and inconvenient than monotherapy with proton pump inhibitors.19

Nevertheless, because of their excellent safety profile, H2 blockers are useful in some patients with mild gastro-oesophageal reflux disease when they can be taken as needed. Their availability as over the counter drugs is currently being evaluated,20 and they may eventually partly replace antacids. Special formulations (such as a wafer or effervescent tablets) may be more appropriate for this use.21,22

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors act at the final step in acid secretion by blocking H+/K+ ATPase irreversibly in gastric parietal cells. Omeprazole (20 and 40 mg daily) was the first proton pump inhibitor extensively evaluated in reflux oesophagitis, and lansoprazole (30 mg daily) and pantoprazole (40 mg daily) have also been used. A recent meta-analysis of 43 therapeutic trials conducted in patients with moderate or severe oesophagitis confirmed the advantage of proton pump inhibitors over H2 blockers.23 The proportion of patients successfully treated was nearly doubled with proton pump inhibitors, and the rapidity of healing and symptom relief were about twice that with H2 blockers. Their superiority is also clear in mild oesophagitis and patients with negative endoscopy results.24 Omeprazole (20 mg or 10 mg daily) has also been shown to be better than cisapride.25 Quality of life is restored to normal with omeprazole.25

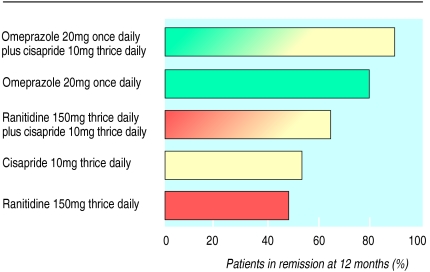

The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors is maintained with time,19 and a meta-analysis of long term trials26 has confirmed that continuous maintenance therapy with omeprazole (20 mg or 10 mg daily) achieves significantly better results than maintenance with 150 mg ranitidine twice daily (figure). Interestingly, the relief of heartburn during omeprazole treatment is highly predictive of healing.26 Therefore, no further endoscopic investigation is required in asymptomatic patients taking proton pump inhibitors (unless initial endoscopy shows severe oesophagitis or complications). Many patients with mild disease do not require continuous maintenance therapy. Recent studies have shown excellent results for symptom relief and quality of life with omeprazole on demand (20 or 10 mg daily).27

The main issue concerning prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is safety. Although proton pump inhibitors are well tolerated, some concern exists about the risk of malignancy after 10 or 20 years of potent acid suppression. Proliferation of endocrine cells has been reported in relation to hypergastrinaemia as a result of hypochlorhydria, which is non-specific for proton pump inhibitors. In fact, the risk of endocrine neoplasia seems extremely low and of no clinical relevance for most patients, whereas that of developing atrophic gastritis (a premalignant condition for adenocarcinoma) is more important and deserves more complete evaluation.28 Since the risk of atrophic gastritis seems related to Helicobacter pylori infection some authors recommend eradication of this bacterium before embarking on long term acid suppression. However, the benefit of this strategy is not yet adequately demonstrated.

Antireflux surgery

The principle of every surgical procedure, whether open surgery or laparoscopic repair, is to restore an anti-reflux barrier by recreating a sufficient pressure gradient in the distal oesophagus and to close the hiatal hernia.

Open surgery

Excellent results can be obtained with different procedures such as total fundic wrap (Nissen operation) or partial fundoplications (such as Toupet’s procedure). The preferred and probably most efficient anti-reflux procedure is the “floppy” Nissen fundoplication, which has been developed to avoid the side effects of the original fundic wrap (dysphagia, gas bloat syndrome, and inability to burp). Success rates of up to 90% can be achieved, with almost no mortality and morbidity. After 10 to 20 years some deterioration can occur, usually associated with wrap disruption.29

Laparoscopy

The technical aspects of laparoscopic fundoplication have been extensively described. Routine use of a postoperative nasogastric tube is unnecessary, and a soft diet is introduced on the first postoperative day. Patients are generally discharged by the first or second postoperative day and are usually able to return to work within two weeks after their operation. However, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is a demanding technique and requires different skills from other procedures such as cholecystectomy. The learning curve is a determining factor in the rate of the postoperative complications.30 Severe complications are noted in 0.5-2% of cases.31 Oesophageal perforation, a potentially lethal complication, occurs in 0.5-1.5% of all cases and is related to the surgeon’s expertise.

Postoperative dysphagia, with or without reflux symptoms, can also complicate laparoscopic repair.32 Final success rates range from 90% to 100%, and follow up in most (retrospective) series does not exceed one year. In a prospective randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open Nissen fundoplication Watson et al observed no difference in relief of symptoms at three months.33

No trials have compared modern medical and surgical treatments of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, although some are in progress. In men with complicated gastro-oesophageal reflux disease open surgery is significantly more effective than traditional medical treatment (ranitidine, metoclopramide, antacids, and sucralfate) in improving symptoms and oesophagitis for up to two years.34

How to manage gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease depends mainly on age (and concomitant illness), severity of symptoms and oesophagitis, and outcome of initial treatment.

Initial treatment

In patients with mild or moderate heartburn the first approach is usually to combine lifestyle modifications with alginate-antacids. This is adequate to relieve symptoms in a large proportion of patients presenting to general practice. However, in young adults presenting with no alarming symptoms (such as dysphagia, anaemia, or weight loss) there is now good consensus on use of acid suppressors without endoscopic assessment. Short courses of H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors can be given without risk of missing a life threatening condition. In patients over 45 years of age and those with alarming symptoms, endoscopy is mandatory to exclude malignancy and assess the severity of oesophagitis, which is an important predictor of therapeutic response. When endoscopy gives normal results in a patient with atypical symptoms the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease should be established before any treatment is recommended. Twenty four hour pH monitoring with symptom analysis may be useful, although a trial of proton pump inhibitors may be a more attractive and cheaper option. Rapid relief of symptoms seems to have good sensitivity for diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, but the results need to be confirmed in further prospective studies.35

In patients with negative endoscopy results and those with mild oesophagitis two options are now available. Firstly, the classic stepwise approach (with cisapride or H2 blockers as the first treatment and proton pump inhibitors given only to non-responders) or, secondly, a top down strategy, starting with proton pump inhibitors and titrating down to lower doses or a less effective acid suppressor or prokinetic. There is no definite evidence from randomised clinical trials to recommend one or the other of these strategies, although the top down approach may ultimately be more cost effective.36

In patients with moderate or severe oesophagitis proton pump inhibitors are the mainstay of treatment. Insufficient response should be managed by gradually increasing the dose. Few patients are resistant to proton pump inhibitors, and such an eventuality should lead to reconsideration of the diagnosis and functional investigations, especially pH monitoring to control the efficacy of the proton pump inhibitor regimen. Non-responders to proton pump inhibitors do not seem to be good candidates for surgery, except those with persisting regurgitation.

Some cases require more specific management. Peptic strictures are usually successfully managed by endoscopic dilatation combined with proton pump inhibitors,37 which are more cost effective than H2 blockers.38 Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus are at risk of developing adenocarcinoma,39 but the need for endoscopic and histological surveillance depends on the general state of the patient. Neither surgery nor specific drug treatment has been shown to reduce the risk of malignancy. Trials combining photoablation of Barrett’s metaplasia and proton pump inhibitors are in progress.40

Long term management

In most cases relief of symptoms and healing of oesophagitis can be achieved after adequate initial treatment. The key issue is long term control of the disease. Intermittent, on demand drug treatment is suitable for patients with mild or moderate symptoms and infrequent relapses. However, if symptoms recur shortly after treatment has been stopped, maintenance treatment (usually with proton pump inhibitors) is highly effective and certainly the best option for older patients or those at risk from surgery. Surgery may be preferable to a lifetime of drug treatment for a young fit patient with frequent relapses.41 Laparoscopic surgery is now the preferred approach for many patients and surgeons. However, even the economic benefit of this strategy over proton pump inhibitors remains to be established and will probably require more than 10 years of follow up evaluation.42 Therefore, caution is required before the indications for laparoscopic surgery are extended. Ideally, this procedure should be performed only in specialist centres with expertise in managing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Figure.

Comparison of five maintenance strategies in prevention of relapse of reflux oesophagitis19 (reproduced with permission)

References

- 1.Galmiche JP, Bruley des Varannes S. Symptoms and disease severity in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(suppl 201):62–68. doi: 10.3109/00365529409105366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spechler SJ. Epidemiology and natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992;51(suppl 1):24–29. doi: 10.1159/000200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heading RC. Long-term management in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30(suppl 213):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer WA, Tytgat GNJ. Review article: drug therapy for reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:147–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahrilas PJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. JAMA. 1996;276:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg DS, Kadish SJ. The diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Med Clin N Amer. 1996;80:411–429. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitchin LI, Castell DO. Rationale and efficacy of conservative therapy for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:448–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sontag SJ, O’Connel S, Khandelwal S, Miller T, Memchausky B, Schnell TG, et al. Most asthmatics have gastro-oesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. Gastroenterology. 1990;9:613–620. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90945-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey RF, Hadley N, Gill TR, Beats BC, Gordon PC, Long DE, et al. Effects of sleeping with the bed-head raised and of ranitidine in patients with severe peptic oesophagitis. Lancet. 1987;ii:1200–1203. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarpignato C, Galmiche JP. Antacids and alginates in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: how do they work and how much are they clinically useful? In: Scarpignato C, editor. Advances in drug therapy of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Basle: Karger; 1992. pp. 153–181. . (Frontiers in Gastrointestinal Research Vol 20.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DY, Smith JL, Patterson DJ. Why do apparently healthy people use antacid tablets? Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poynard T French Cooperative Study Group. Relapse rate of patients after healing of oesophagitis—a prospective study of alginate as self-care treatment for 6 months. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:385–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tytgat GNJ, Janssens J, Reynolds JF, Wienbeck M. Update on the pathophysiology and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the role of prokinetic therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:603–611. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199606000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum AL, Adami B, Bouzo MH, Branstatter G, Fumagalli I, Galmiche JP. Effect of cisapride on relapse of esophagitis. A multinational placebo-controlled trial in patients healed with an antisecretory drug. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:551–560. doi: 10.1007/BF01316514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarpignato C, Galmiche JP. Management of symptomatic GORD: the role of H2-receptor antagonists in the era of proton pump inhibitors. In: Lundell L, ed. Guidelines for management of symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. London: SP Science Press (in press).

- 16.Colin-Jones DG. The role and limitations of H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(suppl 1):9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilder-Smith CH, Merki HS. Tolerance during dosing with H2-receptor antagonists. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27(suppl 193):14–19. doi: 10.3109/00365529209096000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orr WC, Robinson MG, Humphries TJ, Antonello J, Cagliola A. Dose-response effect of famotidine on patterns of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1988;2:229–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1988.tb00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, et al. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt S. Over-the-counter histamine H2-receptor antagonists. How will they affect the treatment of acid-related diseases? Drugs. 1994;47:1–11. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199447010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson RGP, Johnston BT, Tham TCK, Kersey K. Effervescent and standard formulations of ranitidine—a comparison of their pharmacokinetics and pharmacology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:913–918. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.69240000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz JI, Yeh KC, Berger ML, Tomasko L, Hoover ME, Ebel DL, et al. Novel oral medication delivery system for famotidine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35:362–367. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiba N, De Cara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–1810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bate CM, Griffin SM, Keeling PWN, Axon ATR, Dronfield MW, Chapman RWG, et al. Reflux symptom relief with omeprazole in patients without unequivocal oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:547–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.44186000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galmiche JP, Barthelemy P, Hamelin B. Treating the symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind comparison of omeprazole and cisapride. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:765–773. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlsson R, Galmiche JP, Dent J, Lundell L, Frison L. Prognostic factors influencing relapse of oesophagitis during maintenance therapy with antisecretory drugs: a meta-analysis of long-term omeprazole trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:473–482. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardhan KD, Muller-Lissner S, Bigard MA, Bianchi Porro G, Ponce J, Hosie J, et al. Symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: intermittent treatment with omeprazole and ranitidine as a strategy for management [abstract] Gastroenterology. 1997;112(suppl 4):A165. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, Festen HP, Liedman B, et al. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1018–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604183341603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luostarinen M, Isolauri J, Laitinen J, Koskinen M, Keyrilainen O. Fate of Nissen fundoplication after 20 years. A clinical, endoscopical, and functional analysis. Gut. 1993;34:1015–1020. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Baigrie RJ, Mathew G, Devitt PG, Game P, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux: beyond the learning curve. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1284–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collet D, Cadiere GB. Conversions and complications of laparoscopic treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg. 1995;169:622–626. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Waring P. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery: the impact of operative technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224:51–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson DI, Gourlay R, Globe J, Reed MWR, Johnson AG, Stoddard CJ. Prospective randomised trial of laparoscopic (LNF) versus open (ONF) Nissen fundoplication [abstract] Gut. 1994;35(suppl 2):S15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spechler SJ. Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs gastro-oesophageal reflux disease study group. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203193261202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindlbeck NE, Klauser AG, Voderholzer WA, Müller-Lissner SA. Empiric therapy for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1808–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillman AL. Economic analysis of alternative treatments for persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29(suppl 201):98–102. doi: 10.3109/00365529409105374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, Ross BA, Bate CM, Brown P, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1312–1318. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo J, Koehler RE, Spenney JG, Mills TP, et al. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:907–915. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS. Barrett’s oesophagus—cancer risk, biology and therapeutic management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berenson MM, Johnson TD, Markowitz R. Buchi KN, Samowitz WS. Restoration of squamous mucosa after ablation of Barrett’s esophageal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1686–1691. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90646-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anvari M, Allen C, Borm A. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is a satisfactory alternative to long-term omeprazole therapy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:938–942. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heudebert GR, Marks R, Wicox CM, Centor RM. Choice of long-term strategy for the management of patients with severe esophagitis: a cost utility analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1078–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]