Abstract

Exercise elicits physiological adaptations, including hyperpnea. However, the mechanisms underlying exercise-induced hyperpnea remain unresolved. Skeletal muscle acts as a secretory organ, releasing irisin (IR) during exercise. Irisin can cross the blood–brain barrier, influencing muscle and tissue metabolism, as well as signaling in the central nervous system (CNS). We evaluated the effect of intracerebroventricular or intraperitoneal injection of IR in adult male rats on the cardiorespiratory and metabolic function during sleep–wake cycle under room air, hypercapnia and hypoxia. Central IR injection caused an inhibition on ventilation (VE) during wakefulness under normoxia, while peripheral IR reduced VE during sleep. Additionally, central IR exacerbates hypercapnic hyperventilation by increasing VE and reducing oxygen consumption. As to cardiovascular regulation, central IR caused an increase in heart rate (HR) across all conditions, while no change was observed following peripheral administration. Finally, central IR attenuated the hypoxia-induced regulated hypothermia and increase sleep episodes, while peripheral IR augmented CO2-induced hypothermia, during wakefulness. Overall, our results suggest that IR act mostly on CNS exerting an inhibitory effect on breathing under resting conditions, while stimulating the hypercapnic ventilatory response and increasing HR. Therefore, IR seems not to be responsible for the exercise-induced hyperpnea, but contributes to the increase in HR.

Keywords: Myokine, Ventilation, Heart rate, Sleep

Subject terms: Respiration, Homeostasis

Introduction

In humans, during conditions of light or moderate physical exercise, partial pressures of blood gases change minimally, despite of the increase in metabolic rate as a result of physical activity1,2. Therefore, for more than a century there has been intense interest in the elucidation of how respiratory neurons adjust their activity, specially in response to physical exercise, since exercise hyperpnea is not associated with an increase in PaCO2 or a decrease in PaO23. Despite the initial hypothesis that lactic acidosis would be the necessary stimulus to increase ventilation during intense exercise, Jeyaranjan et al.4 described that this stimulus is not an essential determinant of the exercise-induced hyperpnea. Further, as recently reviewed by Welch and Mitchell5, evidence suggests that both central and peripheral neurogenic factors contribute to exercise-induced hyperpnea. However, controversy surrounds these findings, and none of the proposed mechanisms, even when combined with feedback mechanisms, fully explain exercise hyperpnea. Therefore, other mediators, such as myokines, may be part of this signaling pathway between muscle activity and respiratory rhythm adjustments.

It is widely known that skeletal muscle generates antioxidant and hypoglycemic responses during physical activity6. The most plausible cellular explanations focus on the production of muscle cytokines, both by the endocrine system and paracrine action, the so-called myokines7,8. Irisin is a myokine composed by 112 amino acids, derived from a type 1 membrane protein present in myocytes and is encoded by the fibronectin type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5)9,10. More specifically, FNDC5 results in a protein formed by a signal peptide with 29 amino acids and has 100% similarity between rats and humans11. During physical activity, the contraction generated by muscles promotes activation of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) signaling pathways that stimulate the expression of proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α). The increase in PGC-1α in the cell drives the nucleus to a transcription process that will give rise to FNDC5. The production of IR occurs from enzymatic cleavage of FNDC5 carried out by the enzyme of the desintegrin and metalloproteinase family12–14.

Previous study has demonstrated that irisin, despite to be a large molecule, can cross the blood brain barrier (BBB)15. Irisin can stimulate the expression of the myokine brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the brain, an important signaling molecule for synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis15. Interestingly, lactate produced by the skeletal muscle resulting from exercise can stimulate the production of irisin in the brain in a PGC-1α-dependent manner16. Hence, given its widespread influence, irisin likely plays a role in facilitating the hyperpnea during exercise. However, no study has specifically assessed the involvement of this myokine in regulating respiration and the role of irisin in peripheral and central chemoreflex.

It is widely recognized that physical exercise, along with central and peripheral chemoreflex activation, not only affects ventilation promoting hyperpnea and enhancing CO2 and O2 chemosensitivity17–19, but also triggers significant cardiovascular, metabolic, and thermoregulatory adjustments20,21. Therefore, irisin may also play a role in regulating these adjustments. In fact, previous studies show that irisin converts white adipose tissue into brown adipose tissue, activating thermogenesis, mainly by upregulating the UCP1 expression through enhanced energy expenditure9. Since then, multiple other functions have been described such as that irisin stimulates neuroplasticity in the brain22, participates in cardiovascular control23, and has effects on sleep quality24,25.

In the present study, the experiments were undertaken to evaluate the participation of central and peripheral irisin in the cardiorespiratory and metabolic regulation under room air conditions, hypoxia and hypercapnia in adult rats. Since central respiratory control system is strongly influenced by vigilance state26, we compare the responses during sleep and wakefulness.

Material and methods

Animals

The experiments were performed in male adult Wistar rats, weighting 300–350 g. All the animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room, maintained at 25 ± 1 °C with a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 6:30 a.m.), with water and food provided ad libitum. Experiments were performed between 7:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m at the Department of Animal Morphology and Physiology of the Faculty of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences (FCAV- UNESP, Jaboticabal campus). All protocols were approved by the local ethics committee called “Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animal” (CEUA—protocol no 3337/20), following the rules of the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA-Brazil). Furthermore, all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and reporting in the manuscript follows the recommendations in the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0.

Irisin treatment and gas mixture exposure

Irisin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI—EUA) was diluted in Tris buffer (0.05 M, pH ~ 8.0). This solution was used as vehicle for the control animals. We tested two concentrations of irisin, 0.425 and 1.66 μg/μL that correspond to the doses of 1.21 and 4.74 μg/kg respectively (based on the study of Zhang et al.23,27). Both concentrations were applied in the 4th brain ventricle (central; i.c.v.), whereas the higher concentration applied peripherally in different animals (peripheral i.p). The ventilatory challenges were accomplished using gas mixtures of hypercapnia (7% CO2, 21% O2, balance N2) and hypoxia (10% O2, balance N2) purchased from White Martins Gases Industrials Ltda (Osasco, SP, Brazil).

Implantation of cannula in the 4th ventricle, electromyogram (EMG) and electroencephalogram (EEG)

One week prior to the experimental day, the rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (100 e 10 mg/kg, respectively). Then, the animals were fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Kent, England) and a stainless-steel guide cannula (15 mm in length and 0.7 mm in external diameter) was implanted in the fourth ventricle, according to the coordinates adapted from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson28 (AP: − 11.9 mm from the bregma, LL: 0 mm, DV: − 6.7 mm from the skull). The cannula was fixed to the skull using dental acrylic and sealed with a mandrel to prevent occlusion and infection.

After this procedure, three electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes were screwed into the skullcap: frontal electrode at 2 mm anterior to bregma and 2 mm lateral to the midline; parietal electrode at 4 mm anterior to the lambda and 2 mm lateral to the midline; and the third one, laterally between the frontal and parietal electrodes forming a triangle. For electromyogram (EMG) recordings, two electrodes were inserted deep into the neck musculature of the rats. All the electrodes were fixed to the animal’s head using a mini connector that was also soaked in acrylic cement. At the end, the animals were treated with antibiotic (enrofloxacin, 10 mg/kg, subcutaneous) and analgesic (flunixin meglumine, 2.5 mg/kg, subcutaneous) agents followed by the next 3 days and kept in cages up to two animals.

The signals from the EEG and EMG electrodes were sampled at 150 Hz, filtered at 0.3–50 and 0.1–100 Hz, respectively, and recorded on a computer with a data analysis software (AcqKnowledge MP150, BioPac Systems, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Wakefulness, rapid eye movement (REM) or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep states were registered constantly throughout the experiments. REM sleep periods were excluded from analysis since the events occurred shortly and irregularly between the experiments. The sleep/wake state was determined by analyzing the EEG and EMG records as previously described29–31, allowed cardiorespiratory and metabolic variables analyses during different phases of the sleep/wake cycle.

Cardiovascular, blood gases and body temperature measurements

One day before the experiment, the rats received an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine for another surgery procedure. This surgery consisted of insertion of a catheter [PE-10 connected to PE-50 (Clay Adams, Parsippany, NJ, USA)] into the abdominal aorta through the femoral artery, to allow pulsatile arterial pressure (PAP) and blood gases measurements. The catheter was externalized in the animal’s dorse close to the neck region. On the experiment day, the catheter was connected to the pressure transducer (TSD 104A, Biopac systems), the signal was amplified (DA 100C, Biopac systems) and digitized on a computer equipped with data acquisition software (MP100ACE; Biopac Systems). Systolic (SAP) and diastolic (DAP) arterial pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were quantified from the PAP recording using the LabChart program (Power-Lab System, ADInstruments®/Chart Software, version 7.3, Sydney, Australia).

For body temperature (TB) measurements, a temperature datalogger (SubCue Dataloggers, Calgary, Canada) was inserted into the abdominal cavity through a midline laparotomy, at the same surgical procedure. The datalogger was programmed to acquire data every 5 min.

Central and peripheral treatments

For i.c.v., a Hamilton syringe (5 μL) and a needle (Mizzy, 200 μm of external diameter) where the tip was connected to a PE-10 polyethylene tube that connected to a 30 G gingival needle (15.5 mm long), was used to perform microinjections in the 4th ventricle. The volume of injections was 1 μL for 1 min using a microinjector machine (model 310, Stoelting Co., Il, EUA). For i.p. injections, the volume was established according to the animal’s body weight (1 mL/kg), and the injection was performed over a period of 15 s.

Pulmonary ventilation assessment

Ventilation (VE) was recorded by using whole body plethysmography—closed system32,33. The chamber was sealed for approximately 2 min. The pressure oscillation due to temperature difference from inhaled and exhaled air were monitored by a differential pressure transducer (TSD 160A, Biopac Systems, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) and fed into a pre-amplifier (DA 100C, Biopac Systems), passed through an analog-to-digital converter and digitized on a computer equipped with data acquisition software (MP100ACE, Biopac Systems). The sampling frequency was 200 Hz. A volume calibration was performed by injecting 1 mL of air into the chamber using a graduated syringe. Tidal volume (VT) was calculated applying Drorbaugh and Fenn’s formula:32

where PT: pressure deflection associated with each VT, PK: pressure deflection associated with the injection of the calibration volume (VK), TA: air temperature in the animal chamber, PB: barometric pressure, PC: water vapor pressure in the animal chamber, TB: body temperature (in Kelvin), and PR: water vapor pressure at TC. VE was calculated as the product of respiratory frequency (fR) and VT and divided to the animal’s body weight. VE and VT were presented under ambient barometric pressure conditions at TB and saturated with water vapor (BTPS). PC and PR were calculated indirectly considering temperature and water vapor saturated air34. The LabChart software (PowerLab System, ADInstruments®/LabChart Software, version 7.3, Sydney, Australia) was used for data analysis.

Determination of oxygen consumption

The indirect calorimetry method by measuring O2 consumption (VO2) with flow- through push mode configuration in an open respirometry system was used for metabolic rate inference35,36. The chamber air flow (2.2 L/min−1) was maintained through an aquarium pump that directed the air to the chamber entrance when the animals were exposed to ambient air and by gas mixture cylinders coupled to a flowmeter (model 822-13-OV1-PV2-V4, Sierra Instruments, Monterey, CA) when exposed to hypercapnia or hypoxia. The expired gas was dried over a small column of Drierite (W.A. Hammond Drierite Co. Ltd, Xenia, OH, USA) before entering the analyzer. The air was continuously sampled allowing for the determination of VO2 by a data acquisition program (Power-LabSystem, ADInstruments®/Chart Software, version 7.3, Sydney, Australia). CO2 was not analyzed or removed, then aiming at a better metabolic rate measurement the VO2 was calculated using the following equation:37

where FRe: end flow rate of air through the chamber, FiO2: inlet O2 fraction, FeO2: end O2 fraction, and RQ: respiratory quotient (considered to be 0.85). The VO2 was corrected for STPD (standard temperature pressure dry) and divided for body mass.

Blood gases and pH measurements

Blood gases, pH and bicarbonate were measured in the following groups: i.c.v. or i.p.—Irisin and vehicle at room air, hypercapnia and hypoxia. Two drops of blood were sampled for immediate analyses of arterial pH (pHa), arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) and plasma bicarbonate (HCO3−). These samples were transferred to an ECG8 + cartridge to be read in an i-STAT blood gas portable analyzer (i-STAT Analyzer, Abbott Laboratories, Libertyville Township, IL, USA).

Experimental protocol

The animals were previously placed inside a plethysmography chamber and TB was recorded in the data logger every 5 min. Initially, the chamber was ventilated with atmospheric air (21% O2), during a habituation time of 60 min. Then, the resting VE, VO2 e HR were measured in room air throughout 60 min. Following, the animals received an i.c.v. or i.p. injection of irisin or vehicle. After the injection, the animals were exposed to atmospheric air (21% O2), hypercapnia (7% CO2) or hypoxia (10% O2) during 60 min. For every condition of exposure, different animals were utilized. Ventilation was recorded for two minutes, during the baseline O2 recording, each 10 min during the exposure time. The arterial blood gases were made previously and 15 min after the microinjection. The VO2, HR, TB measurements and EEG/EMG signals were recorded throughout the experiment.

Determination of the heat loss index

In order to infer about the peripheral vasodilation or vasoconstriction of the animals that received the treatment with irisin or vehicle during exposure to hypoxia, we evaluated the heat loss vs conservation through the skin of the tail (TS). This protocol was performed according to Cristina-Silva et al.38. One week prior to the experimental day, the rats were anesthetized with i.p. injection of ketamine and xylazine (100 e 10 mg/kg, respectively) and were submitted to surgical procedure for the implantation of guide cannula in the 4th ventricle, as described above. One day before the experiment, the animals were anesthetized for the datalogger (SubCue Dataloggers, Calgary, Canada) implantation into the abdominal cavity through a midline laparotomy. The datalogger was programmed to acquire data every 1 min. The TS and the ambient temperature (TA) were measured by using an infrared-sensitive camera (Flir SC660, Portland, OR, USA). The ambient temperature was maintained at ~ 25 °C and the animals were habituated in the chamber ventilated with atmospheric air (21% O2), during 30 min. Next, the thermographic camera was programed to take images under room air condition every 1 min during 30 min. Then, the microinjection (1 µL) of irisin 1.66 µg/µL or vehicle was performed through the guide cannula. After the injection, the animals were exposed to hypoxia (10% O2) during 30 min and imagens were taken at 1 min interval. Through thermographic images we were able to obtain the average of TS and TA. The images during hypoxia were analyzed between 10 and 15 min, the peak moment of tail vasodilation caused by hypoxia39. Images were analysed using the Flir Tools® software (Flir Systems, OR, USA). The TB and TS were used to infer the heat loss index (HLI) of the animal, which ranges from 0 to 1 (where 0 indicates maximum vasoconstriction and 1 is maximum vasodilation), and was calculated according to the equation:40

Confirmation of the microinjection

At the end of the experiments, the animals were deeply anesthetized and received a microinjection of 1 μL of Evans blue solution (2%) via the central guide cannula to verify the location and distribution pattern of central microinjection. The animals were perfused through the left ventricle of the heart with 60 mL of sterile saline followed by 60 mL of 10% formalin. Then, the animals were decapitated, the brain was removed and sectioned for identification and confirmation of the microinjection site. Figure S1 displays images of a representative animal with a positive microinjection site on the 4th ventricle. Only the animals that showed blue coloration in this region were incorporated into the data analysis.

Data analyses

Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. The effects of IR and vehicle on VE, fR, VT, VO2, VE/VO2 and HR were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA and the animals were grouped according to sleep or wakefulness in each exposure condition. Approximately 2 min of recordings were used for respiratory (VE, fR, VT), metabolic (VO2) and cardiovascular (MAP, HR) measurements. None of the treatments altered MAP, therefore this data is not shown. Post-hoc multiple comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test when data were normally distributed to assess the differences among the treatments.

Data of blood gases, HLI, TS and TB were analyzed using two-way ANOVA. The analysis of sleep and wakefulness was conducted following the methodology outlined in the study by Vicente et al.41. Sleep and awake states were determined according to the pattern of EEG and EMG waves. Wakefulness was usually characterized by the EEG waves with low amplitude and high frequency and EMG with high activity. The sleep state was characterized by high amplitude and low frequency of EEG waves have and absence of EMG activity. EEG and EMG records were examined to determine the number of episodes, duration, and percentage of time spent by the animals in each state over a recording period of 3600 s. The comparison between the treatments and states was performed by two-way ANOVA repeated measures. The significance level adopted for all results was p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

All protocols were approved by the local ethics committee called “Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animal” (CEUA—protocol no 3337/20), following the rules of the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA-Brazil). We confirm that the authors complied with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Results

Central treatment

Effect of central irisin microinjection on ventilation, metabolism, cardiovascular variables and body temperature under room air, hypercapnic and hypoxic conditions during wakefulness and sleep state

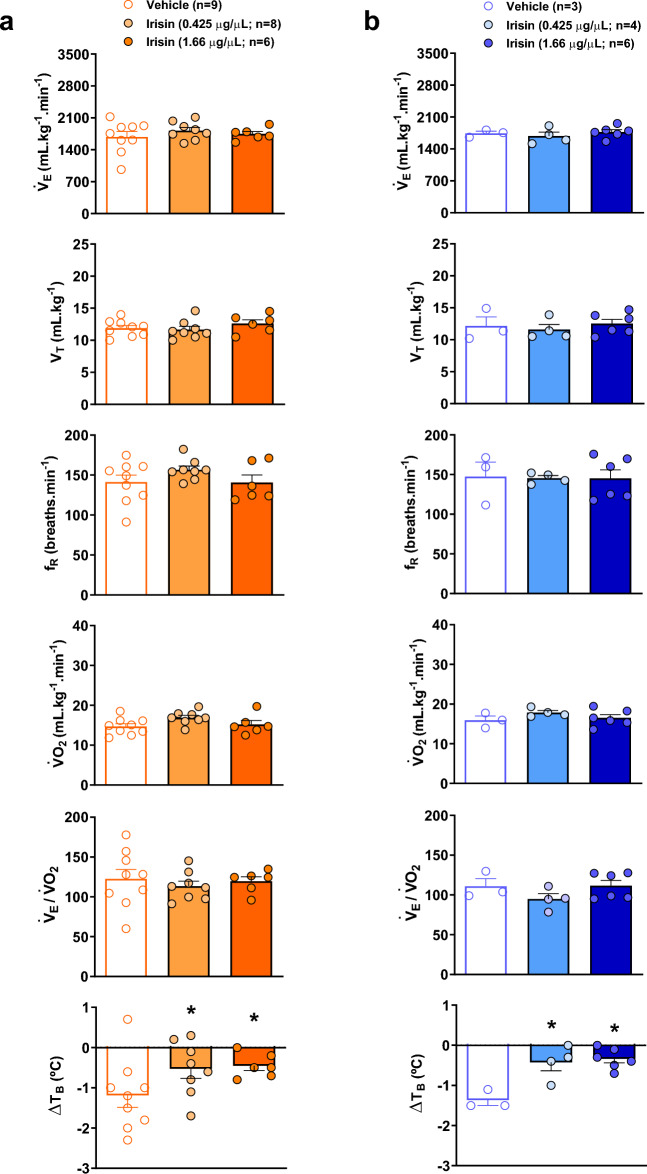

Figure 1 shows VE, VT, fR, VO2, VE/VO2 and TB of control and irisin treated-animals (0.425 and 1.66 µg/µL) during wakefulness (Fig. 1a) and sleep (Fig. 1b) states while exposed to room air. During wakefulness, the central injection of both concentrations of irisin promoted a significant reduction in VE under room air conditions (P < 0.02 for both concentrations), and the highest concentration also reduced the fR (P < 0.02). No difference was observed in VO2 after the treatments. Regarding sleep state, the treatment with the highest IR concentration promoted a reduction in fR, differing from control animals (P < 0.03). Additionally, the treatment with the highest IR concentration caused a reduction in VO2 (P < 0.02) compared to the lowest concentration and, consequently, an increase in VE/VO2 compared to control and the lowest concentration groups (P < 0.02 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Figure 1.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) on ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), respiratory equivalent (VE/VO2) and body temperature (TB) during resting conditions in wakefulness (a) and sleep (b). Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Represents significant difference compared with control group. #Represents significant difference between irisin-treated groups.

Figure 2 presents VE, VT, fR, VO2, VE/VO2 and TB of control and irisin treated-animals during hypercapnia in the awake (Fig. 2a) and sleep (Fig. 2b) state. In wakefulness state, the central microinjection of the highest irisin concentration promoted an increase in VE (P < 0.04) compared to the control hypercapnic animals. The effect was due to a significant change in VT (P < 0.01 for control and P = 0.01 for IR 0.425 µg/µL). The highest concentration promoted a reduction in VO2 compared to control and the lowest concentration groups (P < 0.01 for both groups), as well as an increase in VE/VO2 (P < 0.03 and P < 0.02, respectively) leading to a hyperventilation. No significant differences were observed among treatments during sleep state, in the ventilatory, metabolic and TB variables in hypercapnia.

Figure 2.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) on ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), respiratory equivalent (VE/VO2) and body temperature (TB) during hypercapnia (7% CO2) in wakefulness (a) and sleep (b). Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Represents significant difference compared with control group. #Represents significant difference between irisin-treated groups.

Figure 3 demonstrates the VE, VT, fR, VO2, VE/VO2 and TB of vehicle and irisin treated-animals during hypoxia in the awake (Fig. 3a) and sleep (Fig. 3b) state. Hypoxia caused a drop in TB in the vehicle group, which was attenuated in the animals that received both IR concentrations during awake and sleep state (P < 0.05, for both treatments). The other variables were not affected by the IR treatments in hypoxia.

Figure 3.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) on ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), respiratory equivalent (VE/VO2) and body temperature (TB) during hypoxia (10% O2) in wakefulness (a) and sleep (b). Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Represents significant difference compared with control group.

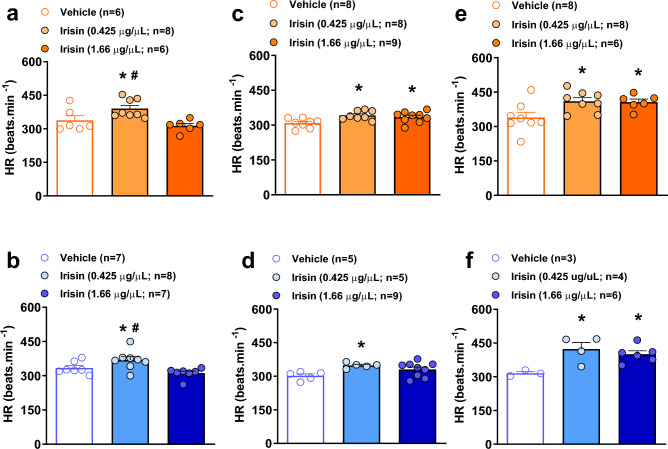

Figure 4 presents the values of HR of the animals treated with irisin or vehicle in wakefulness. During room air conditions, the lowest IR concentration caused an increase in HR compared to control (P < 0.01 and P = 0.05, in awake and sleep states, respectively), and highest concentration (P < 0.01 for both awake and sleep states) (Fig. 4a, b). The microinjection of both IR concentrations resulted in a significant increase in HR (P = 0.01 for IR 0.425 µg/µL and P = 0.05 for IR 1.66 µg/µL) during wakefulness under hypercapnic challenge (Fig. 4c). Likewise, in sleep state, the lower IR concentration also promoted a significant increase in HR compared the control animals (P < 0.03, Fig. 4d). A similar pattern of response was observed under the hypoxic condition, during awake (Fig. 5e) and sleep (Fig. 5f) state. The treatment with both IR concentrations promoted an increase in HR compared to the control animals (P = 0.03, for both treatments in wakefulness; and P = 0.01 for IR 0.425 µg/µL and P = 0.05 for IR 1.66 µg/µL in sleep).

Figure 4.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) on heart rate (HR) during wakefulness (a) and sleep (b) at room air condition, hypercapnia in wakefulness (c) and sleep (d) and hypoxia in awake (e) and sleep (f) states. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Represents significant difference compared with control group within the same exposure condition. #Represents significant difference between irisin-treated groups within the same exposure condition.

Figure 5.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) on the percentage of time spent in each state, the duration of episodes (s) and the number of episodes during room air (a), hypercapnia (b) and hypoxia (c). Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Represents significant difference compared with control group within the same exposure condition. +Means significant difference between awake and sleep state at the same treatment group and exposure condition.

Effect of central microinjection of irisin on arterial pH and blood gases

Table 1 shows the effect of central irisin (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) microinjection on pHa, PaCO2, PaO2 and HCO3− during room air conditions, hypercapnia and hypoxia. For all groups, exposure to 7% CO2 resulted in a decrease in pHa, increases in PaCO2, PaO2 and HCO3- compared to room air conditions and hypoxia (P < 0.001, for all variables and conditions). Low environmental O2 condition caused an increase in pHa and a decrease in PaCO2 and PaO2 when compared to normoxia (P < 0.001, for all variables). Additionally, the animals treated with the highest IR concentration showed a significant increase in pHa and a decrease in the PaCO2 (P = 0.03 for both variables) during room air conditions, in addition to lower PaCO2 (P = 0.01), and HCO3− (P < 0.02) when compared to the vehicle group during hypercapnia.

Table 1.

Values of arterial pH (pHa), arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) and plasma bicarbonate (HCO3−) 15 min after microinjection of vehicle or irisin (0.425 or 1.66 µg/µL) at room air, hypercapnic and hypoxic condition.

| Vehicle | Irisin (0.425 µg/µL) | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room air (n = 7) | Hypercapnia (n = 8) | Hypoxia (n = 7) | Room air (n = 7) | Hypercapnia (n = 7) | Hypoxia (n = 7) | Room air (n = 7) | Hypercapnia (n = 7) | Hypoxia (n = 5) | |

| pHa | 7.42 ± 0.01 | 7.33 ± 0.01#+ | 7.60 ± 0.01# | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 7.32 ± 0.01#+ | 7.61 ± 0.01# | 7.46 ± 0.01* | 7.30 ± 0.01#+ | 7.60 ± 0.01# |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 36.1 ± 1.8 | 52.2 ± 1.9#+ | 19.7 ± 1.2# | 32.0 ± 1.0 | 47.7 ± 2.5#+ | 19.4 ± 1.2# | 28.0 ± 1.6* | 44.2 ± 3.2#+* | 18.8 ± 1.6# |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 89.8 ± 3.4 | 118.6 ± 2.2#+ | 31.0 ± 1.2# | 87.8 ± 2.2 | 123.6 ± 2.5#+ | 31.8 ± 1.4# | 88.3 ± 1.7 | 117.1 ± 2.2#+ | 30.4 ± 1.7# |

| HCO3− | 23.2 ± 1.5 | 27.3 ± 1.0+ | 19.4 ± 1.1 | 21.4 ± 0.5 | 24.5 ± 1.5+ | 19.5 ± 1.3 | 19.6 ± 1.0 | 22.2 ± 1.8* | 18.3 ± 1.5 |

*Means significant difference between vehicle and irisin group at the same condition. #Means significant difference when compared with room air at the same treatment group. +Means significant difference between hypercapnic and hypoxic condition at the same treatment group.

Effect of central irisin microinjection on sleep/wakefulness state

Figure 5 shows the effect of central treatment of irisin in the percentage of time spent in each state, and in the duration and the number of episodes in sleep and wakefulness state. During normoxia normocapnia (Fig. 5a), the rats receiving vehicle treatment had lower percentage and length of the episodes in sleep (P < 0.01 for both variables). Regarding the IR-treated rats, both concentrations reduced the percentage of total wakefulness (P < 0.02 for both concentrations) and the length of the episodes in awake (P < 0.01 for both concentrations) compared to the control group. Therefore, treatment with the two IR concentrations promoted an increase in the percentage of total sleep (P < 0.02 for both concentrations) and the duration of episodes in sleep under room air condition (P < 0.05 for both concentrations). The CO2 exposure (Fig. 5b) reduced the percentage of sleep and the duration of episodes in sleep (P < 0.01 for both variables and groups), with no IR effects. Under hypoxic condition (Fig. 5c), the animals that received the vehicle treatment had a lower total percentage and length of the episodes of sleep (P = 0.03 for both variables) without any significant differences among the groups.

Effect of central microinjection of irisin on body temperature and heat loss index under hypoxic conditions

For interpreting the attenuation of the hypoxia-induced regulated hypothermia by IR without change in VO2, we inferred changes in peripheral vasomotion by calculating the HLI from TB, TA and TS (Fig. 6). Figure 6a shows that hypoxia increased HLI in vehicle group (peripheral vasodilation) that occurred concurrently with the TB drop and TS increase. Central IR treatment during hypoxia inhibited the drop of TB and the increase of TS resulting in a lower HLI (Fig. 6a) compared to control animals (P < 0.01 for all variables), indicating peripheral vasoconstriction (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Effect of central irisin microinjection (1.66 µg/µL) on the heat loss index (HLI), tail skin temperature (Ts) and the body temperature (TB) during room air and hypoxia exposure (a). (b) Representative thermographic images of the animals in room air condition and after the microinjection of vehicle or irisin under hypoxia exposure.

Peripheral treatment

Effect of peripheral injection of irisin on ventilation, metabolism, cardiovascular variables and body temperature under room air, hypercapnic and hypoxic conditions during wakefulness and sleep state

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the values of VE, VT, fR, VO2, VE/VO2, TB, HR, the percentage of time spent in each state, in the duration and the number of episodes in sleep and wakefulness state during normoxia normocapnia (Table 2), hypercapnia (Table 3) and hypoxia (Table 4) of animals that received the i.p. treatment with irisin 1.66 µg/µL or vehicle in the awake and sleep states. Under room air conditions, IR treatment did not affect any of the measured variables (Table 2). During hypercapnia in wakefulness, the peripheral injection of IR decreased VO2 and, consequently, increased VE/VO2 compared to the control treatment (P < 0.03 for both variables) (Table 3). Additionally, the exposure to CO2 resulted in a greater decrease in TB in IR-treated rats (P < 0.01). During sleep, IR treatment promoted an attenuation of hypercapnic ventilatory response due to a reduction in VT compared to the vehicle group (P < 0.03 for both variables) (Table 3). As observed in wakefulness, IR treatment also potentiated the CO2-induced hipothermia during sleep (P < 0.04). The exposure to high levels of CO2 reduced the percetange of total sleep, the duration (P < 0.01 for both variables) and the number of episodes of sleep for control and IR animals (P < 0.03). During hypoxic challenge, peripheral IR treatment did not affect any variable (Table 4).

Table 2.

Ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), air convection requirement (VE/VO2), body temperature (TB), heart rate (HR), percentage of time spent in each state, duration and number of awake and sleep episodes for vehicle and irisin (1.66 µg/µL) peripherally treated animals at awake or sleep state under room air conditions.

| Awake | Sleep | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | |

| VE (mL kg−1 min−1) | 808.9 ± 63.0 | 823.8 ± 36.6 | 780.7 ± 41.7 | 815.5 ± 45.6 |

| VT (mL kg−1) | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 8.9 ± 0.2 |

| fR (breaths.min-1) | 91.7 ± 3.9 | 90.2 ± 4.0 | 86.5 ± 4.0 | 91.1 ± 4.1 |

| VO2 (mL kg−1 min−1) | 16.1 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 16.4 ± 0.7 | 16.9 ± 0.5 |

| VE/VO2 | 50.7 ± 3.7 | 51.0 ± 3.7 | 49.1 ± 3.8 | 49.0 ± 3.2 |

| TB (°C) | 38.0 ± 0.3 | 38.2 ± 0.1 | 37.9 ± 0.2 | 38.2 ± 0.2 |

| HR (beats min−1) | 331.6 ± 9.1 | 350.8 ± 13.7 | 328.3 ± 7.6 | 356.3 ± 14.9 |

| % Time spent in each states | 51.4 ± 3.0 | 59.3 ± 4.5 | 48.6 ± 3.0 | 40.7 ± 4.5 |

| Duration of episodes (s) | 1797.5 ± 108.7 | 2113.6 ± 164.7 | 1700.8 ± 108.7 | 1448.6 ± 161.0 |

| Number of episodes | 23.6 ± 1.8 | 21.4 ± 1.7 | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 21.0 ± 1.7 |

Table 3.

Ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), air convection requirement (VE/VO2), body temperature (TB), heart rate (HR), percentage of time spent in each state, duration and number of awake and sleep episodes for vehicle and irisin (1.66 µg/µL) peripherally treated animals at awake or sleep state under hypercapnic conditions.

| Awake | Sleep | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | |

| VE (mL kg−1 min−1) | 2465.7 ± 51.9 | 2361.2 ± 108.4 | 2435.3 ± 50.8 | 2198.0 ± 40.4* |

| VT (mL kg−1) | 15.9 ± 0.3 | 14.2 ± 1.1 | 15.6 ± 0.3 | 13.4 ± 0.6* |

| fR (breaths min−1) | 154.7 ± 4.0 | 168.2 ± 7.6 | 156.4 ± 4.4 | 165.9 ± 9.9 |

| VO2 (mL kg−1 min−1) | 20.0 ± 0.8 | 16.9 ± 1.0* | 17.0 ± 1.3 | 15.4 ± 0.5 |

| VE/VO2 | 125.9 ± 6.5 | 144.4 ± 6.5* | 147.4 ± 10.9 | 146.0 ± 7.7 |

| ∆TB (°C) | − 0.1 ± 0.1 | − 0.6 ± 0.1* | − 0.3 ± 0.1 | − 0.6 ± 0.1* |

| HR (beats min−1) | 319.9 ± 9.8 | 324.1 ± 20.7 | 319.1 ± 7.1 | 324.6 ± 25.7 |

| % Time spent in each states | 70.2 ± 5.9 | 73.1 ± 7.0 | 29.8 ± 5.9+ | 26.8 ± 7.0+ |

| Duration of episodes (s) | 2544.1 ± 219.6 | 2562.0 ± 195.9 | 1075.6 ± 211.1+ | 965.0 ± 260.8+ |

| Number of episodes | 15.3 ± 0.7 | 14.6 ± 1.0 | 14.6 ± 0.8+ | 14.0 ± 1.2+ |

*Means significant difference between vehicle and irisin group at the same state of the sleep–wake cycle. +Means significant difference between awake and sleep state at the same treatment group.

Table 4.

Ventilation (VE), tidal volume (VT), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen consumption (VO2), air convection requirement (VE/VO2), body temperature (TB), heart rate (HR), percentage of time spent in each state, duration and number of awake and sleep episodes for vehicle and irisin (1.66 µg/µL) peripherally treated animals at awake or sleep state under hypoxic conditions.

| Awake | Sleep | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | |

| VE (mL kg−1 min−1) | 1634.1 ± 65.8 | 1566.4 ± 91.7 | 1606.7 ± 64.5 | 1507.7 ± 86.9 |

| VT (mL kg−1) | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 11.4 ± 0.6 | 11.1 ± 0.4 |

| fR (breaths min−1) | 139.4 ± 7.1 | 136.1 ± 6.5 | 143.3 ± 7.3 | 137.5 ± 10.9 |

| VO2 (mL kg−1 min−1) | 15.5 ± 0.9 | 14.7 ± 0.9 | 15.4 ± 0.7 | 14.1 ± 0.3 |

| VE/VO2 | 109.3 ± 7.0 | 112.0 ± 7 | 108.2 ± 3.3 | 108.5 ± 7.6 |

| ∆TB (°C) | − 0.9 ± 0.1 | − 0.7 ± 0.1 | − 0.8 ± 0.2 | − 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| HR (beats min−1) | 388.2 ± 15.7 | 367.0 ± 14.3 | 399.5 ± 27.9 | 358.9 ± 29.7 |

| % Time spent in each states | 55.3 ± 10.3 | 61.2 ± 7.5 | 44.6 ± 10.3 | 38.7 ± 7.5 |

| Duration of episodes (s) | 1865.0 ± 346.0 | 2266.0 ± 307.2 | 1532.0 ± 378.3 | 1413.0 ± 261.6 |

| Number of episodes | 17.4 ± 1.4 | 17.4 ± 1.6 | 16.8 ± 1.4 | 16.8 ± 1.7 |

Effect of peripheral injection of irisin on arterial pH and blood gases

Table 5 presents the effect of i.p. irisin (1.66 µg/µL) injection on pHa, PaCO2, PaO2 and HCO3− during room air, hypercapnia and hypoxia conditions. Under room air conditions, peripheral IR did not cause alterations in blood gases, pHa or HCO3−. Exposure to 7% CO2 resulted in a decrease in pHa, increase in PaCO2 and PaO2 compared to room air conditions and hypoxia (P < 0.001, for all variables and conditions). Hypercapnia exposure also promoted an increase in HCO3− compared to room air condition (P < 0.005, for the IR group) and hypoxia (P < 0.03 for the vehicle group; P < 0.001 for the IR group). Hypoxia promoted an increase in pHa and a decrease in PaCO2 and PaO2 when compared to normoxia (P < 0.001, for all variables) with no difference between groups. The peripheral injection of irisin did not promote significant difference in any of the conditions.

Table 5.

Values of arterial pH (pHa), arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2), arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) and plasma bicarbonate (HCO3−) 15 min after intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or irisin (1.66 µg/µL) at room air, hypercapnic and hypoxic condition.

| Vehicle | Irisin (1.66 µg/µL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room air (n = 5) | Hypercapnia (n = 6) | Hypoxia (n = 5) | Room air (n = 7) | Hypercapnia (n = 5) | Hypoxia (n = 6) | |

| pHa | 7.46 ± 0.01 | 7.33 ± 0.01#+ | 7.63 ± 0.01# | 7.45 ± 0.01 | 7.34 ± 0.01#+ | 7.62 ± 0.01# |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 29.9 ± 1.7 | 43.6 ± 1.6#+ | 17.7 ± 1.7# | 30.0 ± 1.5 | 48.5 ± 1.8#+ | 17.4 ± 1.6# |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 81.8 ± 2.1 | 113.3 ± 1.9#+ | 31.4 ± 2.1# | 80.8 ± 1.8 | 113.2 ± 2.3#+ | 31.6 ± 1.9# |

| HCO3− | 21.3 ± 1.3 | 23.2 ± 1.2+ | 18.4 ± 1.3 | 21.0 ± 1.1 | 26.0 ± 1.4#+ | 18.0 ± 1.2 |

#Means significant difference when compared with room air at the same treatment group. +Means significant difference between hypercapnic and hypoxic condition at the same treatment group.

Discussion

Despite various studies conducted over the past century, the intricate mechanisms governing ventilatory control during exercise remain largely unresolved. Since exercise increases irisin secretion in skeletal muscles in humans and rodent species41,42, we hypothesized that IR may play a role in the augmentation of VE and other physiological adaptations observed during physical activity. Our study demonstrates that IR, when acting on the CNS, exerts a tonic inhibitory effect on breathing control, promotes an increase in sleep period, and modulates heart rate in an excitatory manner. Therefore, it seems that this myokine does not account for the hyperpnea during exercise, but might be related to the cardiovascular adjustments, since an increase in HR was observed. Additionally, we have observed that both central and peripheral IR enhance CO2-induced hyperventilation during wakefulness which is also observed during acute exercise19. Furthermore, our findings provide compelling evidence of a diminished hypothermic response to hypoxia following central IR treatment, as indicated by a reduced HLI. Comparing the central and peripheral treatments with IR, lead us to suggest that the primary impacts of IR on the regulation of heart rate, ventilation, metabolic, and sleep/awake cycle occurs within the CNS.

Under resting conditions, central administration of IR led to a decrease in ventilation, particularly acting on fR, during wakefulness. This effect persisted during sleep, with a sustained impact on fR. Additionally, a decrease in VO2 was observed during sleep, ultimately culminating in a hyperventilatory response. The impact of the relative hyperventilation observed in central IR-treated rats was evident in the blood gas composition. Rats receiving the higher concentration of central IR exhibited a decrease in PaCO2 levels, leading to a subsequent increase in pHa. Therefore, in our study, it is possible that central IR is promoting a more efficient ventilatory response. Notably, peripheral IR treatment did not elicit any change in breathing control during resting conditions, indicating that its effect primarily occurs through the CNS. It is well established that during exercise, the elevation in pulmonary ventilation stems from increased fR and VT, aimed at meeting the increased demands3,43. This must be accomplished efficiently, minimizing oxygen consumption by the respiratory system. Hence, our results contradict our initial hypothesis suggesting that IR could serve as a mediator of the hyperpneic response during exercise, since we observed a decreased VE and fR after IR injection.

During exposure to hypercapnia, central and peripheral treatments with IR promoted a potentiation of the hyperventilation during wakefulness mainly due to a reduction in VO2. In rats injected centrally, besides the alteration in VO2, an augment in the hypercapnic ventilatory response was observed due to an increase in VT. One possibility is that IR acts on the peripheral chemoreflex to enhance the CO2 ventilatory response. However, it is unlikely that this effect stems from an influence on the carotid body, as the hypoxic ventilatory response remained unaffected. Therefore, it is conceivable that IR administration might have influenced brainstem areas, leading to an augmented ventilatory response to CO2. In fact, both humans and rodents, FNDC5/irisin expression has been documented across various brain regions, including the hippocampus, midbrain, cerebellum, hypothalamus, cortex, and medulla oblongata15,44. Furthermore, irisin has been identified in the cerebrospinal fluid15. Interestingly, it is known that sensitivity to CO2 also increased during exercise18,19,45. According to Wright et al.19, in humans, the absence of a correlation between CO2 production and the hypercapnic ventilatory response implies that metabolic demand may not be the primary driving factor behind the heightened hypercapnic chemoreflex. The authors propose that the anticipation of exercise along with feedforward and mechanoreceptor feedback likely contribute to enhancing CO2 respiratory chemosensitivity. Nevertheless, additional studies are necessary to thoroughly investigate this aspect.

Administration of central IR resulted in an elevation in both the percentage of total sleep and the duration of sleep episodes at resting condition, suggesting that this myokine has the potential to enhance sleep quality. This effect could be attributed to a direct action of IR or the activation of BDNF15. A previous study has demonstrated that acute exercise induces the expression of BDNF in the hippocampus, and administering this factor into the rat brain during wakefulness can deepen subsequent non-REM sleep25,46. Furthermore, Kushikata et al.47 reported that administering BDNF by intracerebroventricular injection led to an increase in non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) in both rats and rabbits. Subsequently, Faraguna et al.46 observed that unilateral cortical microinjections of BDNF in rats result in an augmentation of subsequent NREMS. Hence, it is plausible to think that the central treatment with IR induced an upregulation of BDNF expression, potentially contributing to the enhancement of sleep quantity during exposure to normal oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. Additionally, a study involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis, who often experience poor sleep quality, demonstrated lower serum irisin levels in comparison to patients with good sleep quality24.

Irisin was firstly discovered to play a role in the regulation of thermogenesis9. Previous study has demonstrated that central injection of irisin (1, 3 and 10 µM) causes an increase in body temperature in rats at 16, 24, and 48 h of interval after its application48. We did not observe changes in TB in animals treated centrally with irisin or vehicle in both sleep or wake states during room air and hypercapnic conditions. However, peripheral IR treatment increased the hypothermic response under CO2 exposure in both states. It is well known that CO2 promotes peripheral vasodilation49,50 which could increase heat lost and, consequently, decrease TB. IR has also been shown to have a peripheral vasodilator effect48, which could potentiate the CO2 hypothermic response.

Interestingly, the animals that received i.c.v. injection of irisin at both concentrations (0.425 and 1.66 µg/µL) attenuated the drop of TB during hypoxic exposure regardless sleep/wake state. The regulated hypothermia during hypoxia (normally called anapyrexia) is caused by an initial cutaneous vasodilation superimposed latter by thermogenesis inhibition39,51–53. As no effect on O2 consumption was observed, the irisin’s suppressive impact on regulated hypothermia in rats during hypoxia could be attributed to this myokine action on specific regions of the CNS involved in vasomotor control. IR could potentially activate areas responsible for sympathetic control, leading to peripheral vasoconstriction and heat conservation, effect that was accentuated during hypoxia. Notably, IR has been found to co-localize with neuropeptide Y in hypothalamic sections, specifically the paraventricular nucleus54. Moreover, a recent study conducted on zebrafish demonstrated some irisin effects on cardiovascular regulation and cardiac gene expression dependent on a sympathetic/beta-adrenergic pathway55. In the present study, we indeed showed that, in contrast to the vehicle-treated rats, central IR treated animals did not exhibit heat loss through the tail and did not present a significant decrease in TB, despite the fact they show no change in VO2. These results clearly indicate an inhibition by central IR of the hypoxia-induced peripheral vasodilation, thus, demonstrating the potential of IR acting on the CNS to modulate sympathetic activation, affecting heat conservation during adverse conditions such as hypoxia.

Similar to what happens during exercise21, central administration of IR at both concentrations increased HR during sleep and wakefulness states. However, there was no observed change in MAP in any of the conditions or treatments. According to Zhang et al.23, central IR administration increases cardiac output and blood pressure due to activation of neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. On the other hand, another study has reported that the microinjection of irisin into the nucleus ambiguus promotes a significant bradycardic response56. Considering the literature and our findings, the differential effects of IR on HR regulation could be attributed to several factors, including the varying concentrations administered, the specific region of microinjection, and the differences in animal models used. In a study conducted by Brailou et al.56, the effects of IR were evaluated in the nucleus ambiguus, a specific region involved in central parasympathetic cardiac control, where a bradycardic response was observed. In contrast, our study employed a more diffuse injection that likely reached different brainstem regions, including areas involved in central sympathetic cardiac control, such as the rostral ventrolateral medulla57–59. Consequently, the effects of IR on heart rate regulation may depend on the specific CNS region in which this peptide acts.

During exercise, a reduction in the tonic suppressive influence of parasympathetic (vagus) nerve activity contributes increases in HR, ventricular contractility, stroke volume, and thus, cardiac output21. Therefore, given that transcriptome analysis revealed high expression of IR in the medulla oblongata in mice44, where sympathetic and parasympathetic pre-motor neurons are situated, the HR elevation following central IR injection raises intriguing questions about the potential role of FNDC5/irisin in modulating autonomic cardiovascular regulation during exercise. However, further research is warranted to elaborate on these findings.

There are methodological considerations that warrant discussion. Firstly, we lack information on the extent to which peripherally injected IR crosses the blood–brain barrier, making it uncertain to affirm that the effect that we are observing is solely attributable to peripheral action. Therefore, future experiments should aim to quantify IR levels in the CNS following peripheral injection. Secondly, we did not conduct experiments to block IR release during exercise to assess its involvement in cardiorespiratory and metabolic control, thereby validating our hypothesis. Unfortunately, as far as we are aware, there are currently no pharmacological tools available in UpToDate to facilitate these experiments. Thirdly, the experiments were exclusively conducted in male rats, leaving uncertainty regarding the generalizability of the findings to females.

In conclusion, our data strongly suggest that the predominant influence of IR on cardiorespiratory regulation occurs through its action in the CNS. Central treatment with IR with the two concentrations generated a condition of hypoventilation under room air condition due to a lower VE indicating an inhibitory role on breathing control, suggesting that this myokine seems not to be responsible for the exercise-induced hyperpnea. Increasing the concentration of IR potentiated the hyperventilatory response to CO2, promoting an increase in VE and inhibiting the VO2 during wakefulness. In addition, this myokine increased HR and was capable of attenuating the drop in TB under conditions of low O2 levels, which suggest a sympathetic excitatory role of IR. Thus, our results establish IR as a potent bioactive molecule. It also provides the basis for future research on the mechanisms of action of IR, and its role in other physiological processes in rats.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Euclides Roberto Secato for the excellent technical assistance. This work is part of the requirements to obtain a master’s degree by Mariana Bernardes Ribeiro in the Graduate Program in Animal Sciences at UNESP, SP, Brazil. This study was not independently preregistered or has institutional registry.

Author contributions

M. B.-R.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft and review & editing, visualization, funding acquisition. L. G. A. P.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing, visualization. C. C.-S.: methodology, resources, writing—review & editing, visualization. K. C. B.: methodology, resources, writing—review & editing, visualization. L. H. G.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft and review & editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

This work received financial support from Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; 2020/01702-2, 2020/02918-9), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES PrInt; Finance Code 001, Process: 88887.194785/2018-00), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq—302991/20220).

Data availability

All data that support the finding of the current study are available from LHG, upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-62650-7.

References

- 1.Dempsey JA, Rankin J. Physiologic adaptations of gas transport systems to muscular work in health and disease. Am. J. Phys. Med. 1967;46:582–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forster HV, Pan LG, Funahashi A. Temporal pattern of arterial CO2 partial pressure during exercise in humans. J. Appl. Phys. 1986;60:653–660. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.2.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forster HV, Haouzi P, Dempsey JA. Control of breathing during exercise. Compr. Phys. 2012;2:743–777. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeyaranjan R, Goode R, Duffin J. Role of lactic acidosis in the ventilatory response to heavy exercise. Respiration. 2009;55:202–209. doi: 10.1159/000195735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch JF, Mitchell GS. Inaugural review prize 2023: The exercise hyperpnoea dilemma: A 21st-century perspective. Exp. Phys. 2024 doi: 10.1113/EP091506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppeler H. Moderate load eccentric exercise; A distinct novel training modality. Front. Phys. 2016;7:214277. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt C, Pedersen BK. The role of exercise-induced myokines in muscle homeostasis and the defense against chronic diseases. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/52025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.So B, Kim HJ, Kim J, Song W. Exercise-induced myokines in health and metabolic diseases. Integr. Med. Res. 2014;3:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostrom P, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecksteden A, et al. Irisin and exercise training in humans-results from a randomized controlled training trial. BMC Med. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aydin S, et al. A comprehensive immunohistochemical examination of the distribution of the fat-burning protein irisin in biological tissues. Peptides. 2014;61:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu Q, et al. FNDC5/Irisin inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 2019;133:611–627. doi: 10.1042/CS20190016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabbie F, et al. New insights into the cellular activities of Fndc5/Irisin and its signaling pathways. Cell Biosci. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu J, et al. The emerging role of irisin in cardiovascular diseases. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021;10:022453. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrann CD, et al. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metab. 2013;18:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayek LE, et al. Lactate mediates the effects of exercise on learning and memory through SIRT1-dependent activation of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) J. Neurosci. 2019;39:2369–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Oliveira DM, Lopes TR, Gomes FS, Rashid A, Silva BM. Ventilatory response to peripheral chemoreflex and muscle metaboreflex during static handgrip in healthy humans: Evidence of hyperadditive integration. Exp. Phys. 2023;108:932–939. doi: 10.1113/EP091094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weil JV, et al. Augmentation of chemosensitivity during mild exercise in normal man. J. Appl. Phys. 1972;33:813–819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright MD, et al. Peripheral hypercapnic chemosensitivity at rest and progressive exercise intensities in males and females. J. Appl. Phys. 2024;136:274–282. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00578.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delp MD, et al. Exercise increases blood flow to locomotor, vestibular, cardiorespiratory and visual regions of the brain in miniature swine. J. Apply Phys. 2001;533:849–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JP, Young CN, Fadel PJ. Autonomic adjustments to exercise in humans. Compr. Phys. 2015;5:475–512. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon HS, Discer F, Mantzoros CS. Pharmacological concentrations of irisin increase cell proliferation without influencing markers of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in mouse H19–7 hippocampal cell lines. Metabolism. 2013;62:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, et al. Central and peripheral irisin differentially regulate blood pressure. Cardiovas. Drugs Ther. 2015;29:121–127. doi: 10.1007/s10557-015-6580-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamal RM, et al. Preliminary study of the association of serum irisin levels with poor sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Sleep Med. 2020;67:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan X, Van Egmond LT, Cedernaes J, Benedict C. The role of exercise-induced peripheral factors in sleep regulation. Mol. Metab. 2020;42:101096. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nattie EE. Central chemosensitivity, sleep, and wakefulness. Respir. Physiol. 2001;129:257–268. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(01)00295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, et al. Irisin: A myokine with locomotor activity. Neurosc. Lett. 2015;595:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain: In Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nattie E, Li A. CO2 dialysis in nucleus tractus solitarius region of rat increases ventilation in sleep and wakefulness. J. Appl. Phys. 2002;92:2119–2130. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01128.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vicente MC, Dias MB, Fonseca EM, Bícego KC, Gargaglioni LH. Orexinergic system in the locus coeruleus modulates the CO2 ventilatory response. Pflugers Arch. 2016;468:763–774. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leirão IP, Silva CAS, Gargaglioni LH, da Silva GSF. Hypercapnia-induced active expiration increases in sleep and enhances ventilation in unanaesthetized rats. J. Phys. 2018;596:3271–3283. doi: 10.1113/JP274726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drorbaugh JE, Fenn WO. A barometric method for measuring ventilation in newborn infants. Pediatrics. 1955;16:81–87. doi: 10.1542/peds.16.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortola JP, Frappell PB. Measurements of air ventilation in small vertebrates. Respir. Phys. Neurobiol. 2013;186:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dejours P. Principles of Comparative Respiratory Physiology. North-Holland Publishing Company; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mortola JP. Breathing pattern in newborns. J. Appl. Phys. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Phys. 1984;56:1533–1540. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.6.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patrone LGA, et al. Sex- and age-specific respiratory alterations induced by prenatal exposure to the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212–2 in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023;180:1766–1789. doi: 10.1111/bph.16044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koteja P. Measuring energy metabolism with open-flow respirometric systems: Which design to choose? Funct. Ecol. 1996;10:675–677. doi: 10.2307/2390179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cristina-Silva C, Martins V, Gargaglioni LH, Bícego KC. Mu and Kappa opioid receptors of the periaqueductal gray stimulate and inhibit thermogenesis, respectively during psychological stress in rats. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:1151–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-1966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tattersall GJ, Milson WK. Transient peripheral warming accompanies the hypoxic metabolic response in the golden-mantled ground squirrel. J. Exp. Biol. 2003;206:33–42. doi: 10.1242/jeb.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romanovsky AA, Ivanov AI, Shimansky YP. Selected contribution: Ambient temperature for experiments in rats: A new method for determining the zone of thermal neutrality. J. Appl. Phys. 2002;92:2667–2679. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01173.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraemer RR, Shockett P, Webb ND, Shah U, Castracane VD. A transient elevated irisin blood concentration in response to prolonged, moderate aerobic exercise in young men and women. Horm. Metab. Res. 2014;46:150–154. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi H, et al. Exercise-inducible circulating extracellular vesicle irisin promotes browning and the thermogenic program in white adipose tissue. Acta Phys. 2024 doi: 10.1111/apha.14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fregosi RF, Dempsey JA. Arterial blood acid-base regulation during exercise in rats. J. Appl. Phys. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Phys. 1984;57:396–402. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jodeiri Farshbaf M, Alviña K. Multiple roles in neuroprotection for the exercise derived myokine irisin. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:649929. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.649929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pianosi P, Khoo MC. Change in the peripheral CO2 chemoreflex from rest to exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Phys. Occup. Phys. 1994;70:360–366. doi: 10.1007/BF00865034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faraguna U, Vyazovskiy VV, Nelson AB, Tononi G, Cirelli C. A causal role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the homeostatic regulation of sleep. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:4088–4095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5510-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kushikata T, Fang J, Krueger JM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances spontaneous sleep in rats and rabbits. Am. J. Phys. 1999;276:R1334–1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erden Y, et al. Effects of central irisin administration on the uncoupling proteins in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2016;618:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ely SW, Sawyer DC, Scott JB. Local vasoactivity of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the right coronary circulation of the dog and pig. J. Phys. 1982;332:427–439. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puscas I, et al. Carbonic anhydrase I inhibition by nitric oxide: implications for mediation of the hypercapnia-induced vasodilator response. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Phys. 2000;27:95–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barros RCH, Zimmer ME, Branco LGS, Milsom WK. Hypoxia metabolic response of the golden-mantled ground squirrel. J. Appl. Phys. 2001;91:603–612. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tattersall GJ, Milsom WK. Hypoxia reduces the hypothalamic thermogenic threshold and thermosensitivity. J. Phys. 2009;587:5259–5274. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bícego KC, Barros RCH, Branco LGS. Physiology of temperature regulation: Comparative aspects. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A Mol. Integr. Phys. 2007;147:616–639. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrante C, et al. Central inhibitory effectors on feeding induced by the adipo-myokine irisin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016;791:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sundarrajan L, Rajeswari JJ, Weber LP, Unniappan S. The sympathetic/beta-adrenergic pathway mediates irisin regulation of cardic functions in zebrafish. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A Mol. Integr. Phys. 2021;259:111016. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.111016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brailou E, Deliu E, Sporici RA, Brailou GC. Irisin evokes bradycardia by activating cardiac-projecting neurons of nucleus ambiguous. Phys. Rep. 2015;3:12419. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dampney RAL, et al. Medullary and supramedullary mechanisms regulating sympathetic vasomotor tone. Acta Phys. Scand. 2003;177:209–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dampney RAL, Polson JW, Potts PD, Hirooka Y, Horiuchi J. Functional organization of brain pathways subserving the baroreceptor reflex: Studies in conscious animals using immediate early gene expression. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2003;23:597–616. doi: 10.1023/A:1025080314925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Milner TA, Pickel VM. Receptor targeting in medullary nuclei mediating baroreceptor reflexes. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2003;23:751–760. doi: 10.1023/A:1025052903538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the finding of the current study are available from LHG, upon reasonable request.