Abstract

Expression of Proteus mirabilis urease is governed by UreR, an AraC-like positive transcriptional activator. A poly(A) tract nucleotide sequence, consisting of A6TA2CA2TGGTA5GA6TGA5, is located 16 bp upstream of the ς70-like ureR promoter P2. Since poly(A) tracts of DNA serve as binding sites for the gene repressor histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS), we measured β-galactosidase activity of wild-type Escherichia coli MC4100 (H-NS+) and its isogenic derivative ATM121 (hns::Tn10) (H-NS−) harboring a ureR-lacZ operon fusion plasmid (pLC9801). β-Galactosidase activity in the H-NS− host strain was constitutive and sevenfold greater (P < 0.0001) than that in the H-NS+ host. A recombinant plasmid containing cloned P. mirabilis hns was able to complement and restore repression of the ureR promoter in the H-NS− host when provided in trans. Deletion of the poly(A) tract nucleotide sequence from pLC9801 resulted in an increase in β-galactosidase activity in the H-NS+ host to nearly the same levels as that observed for wild-type pLC9801 harbored by the H-NS− host. Urease activity in strains harboring the recombinant plasmid pMID1010 (encoding the entire urease gene cluster of P. mirabilis) was equivalent in both the H-NS− background and the H-NS+ background in the presence of urea but was eightfold greater (P = 0.0001) in the H-NS− background in the absence of urea. We conclude that H-NS represses ureR expression in the absence of urea induction.

Proteus mirabilis causes acute and chronic urinary tract infections including pyelonephritis (2, 7), particularly in patients with long-term indwelling urinary catheters or structural abnormalities of the urinary tract (23). A complication of infection with P. mirabilis is the formation of kidney and bladder stones due to the rise of pH in the urine caused by the hydrolysis of urea by P. mirabilis urease (urea amidohydrolase EC 3.5.1.5) (8, 9).

Urease produced by P. mirabilis contributes to virulence in an animal model of ascending urinary tract infection (12). A urease-negative mutant of P. mirabilis was unable to persist in the urinary tract and caused less histological damage in a mouse model of infection (12) compared to the isogenic wild-type strain. Urea, present at concentrations of up to 500 mM in human urine (8), induces urease production by the bacterium (29). Cultures of wild-type organisms produce only low levels of urease in vitro in the absence of urea induction (13).

The genetic basis for urease induction has been characterized. Urea serves as a cofactor in the transcriptional activation of the urease gene cluster in P. mirabilis (3, 11, 26). In the presence of urea, UreR, an AraC-like positive activator (3, 4, 5, 11, 26), promotes transcription of genes required for the synthesis of urease structural and accessory proteins. These respective polypeptides make up the urease apoenzyme and are responsible for nickel incorporation into the apoenzyme to produce active holoenzyme (22). The direct mechanism of activation of the urease gene cluster is not known; however, it is postulated that UreR changes conformation or forms multimeric complexes upon urea binding and is able to bind avidly to specific DNA sequences in the region of the ureD promoter and up-regulate urease gene expression. AraC-like transcriptional activators are hypothesized to act by interacting directly with RNA polymerase, thus promoting transcription (28). The urease gene cluster in P. mirabilis is organized such that ureR is divergently transcribed relative to the genes encoding urease structural and accessory proteins, the first of which is ureD. An intergenic region (IR), consisting of 492 bp of DNA, separates the start codons for ureR and ureD and has been shown to contain promoter-like sequences for each of these genes (3, 34). Using a gel shift assay, D'Orazio et al. (3) showed that the intergenic region from the homologous plasmid-encoded urease gene cluster found in Providencia stuartii, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella species exhibits decreased mobility in polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels when incubated with whole-cell extracts from E. coli expressing a UreR-His-Tag fusion protein, implying that UreR binds directly to DNA sequences in the intergenic region (3, 34). Putative promoters for both ureR and ureD, based on primer extension studies and analysis of intergenic region deletion constructs, have been assigned according to the results obtained in the aforementioned study. Curiously, the ureR P2 promoter exhibits a strong E. coli ς70-like promoter sequence (TTGTTA–17 bp–TATATT; 4 of 6 and 5 of 6 bp matches for consensus −35 and −10 sequences, respectively), yet ureR does not appear to be expressed at significant levels even when present on multicopy plasmids in E. coli (unpublished observations).

In this study, we investigated the mechanism of repression of ureR and showed that the presence of the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein gene, hns (polypeptide product is H-NS), is responsible for repression of the ureR promoter in E. coli. We also demonstrated that P. mirabilis hns is able to restore repression of the ureR promoter P2 when provided in trans in an H-NS-deficient host background and that the poly(A) tract nucleotide sequence located upstream of P2 contributes to repression of P2 in an H-NS-dependent manner. All strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study are described in Table 1, and cloning procedures were performed as described elsewhere (19).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, plasmid or oligonucleotide | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 λ− gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco-BRL |

| MC4100 | araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR | 32 |

| ATM121 | MC4100 hns::Tn10 Tcr | 20 |

| P. mirabilis HI4320 | Wild-type clinical isolate, Tcr | 14 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector, ori p15A Cmr Tcr | New England Biolabs |

| pBCKS | Cloning vector, ori ColE1 Cmr; used as template for creation of pKHKS303 | Stratagene |

| pBluescriptKS and -SK | Cloning vectors, ori ColE1 Apr | Stratagene |

| pKHKS303 | Cloning vector, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| pLC9801 | pMLB1034-based ureR-lacZ protein fusion construct, ori ColE1 Apr | This work |

| pLX2106 | lacZ operon fusion vector, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| pMLB1034 | lacZ protein fusion vector, ori ColE1 Apr | 31 |

| pRS415 | lacZ operon fusion vector, ori ColE1 Apr | 33 |

| pCC002 | pACYC184 containing ureR driven by the promoter for Tcr, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| pCC007 | pBluescriptSK+ containing the ureR-ureD IR, ori ColE1 Apr | This work |

| pCC037 | pKHKS303 containing PCR-amplified hns from P. mirabilis under T7 promoter control, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| pCC050 | pLX2106 containing PCR-amplified ureR P2 promoter including preceding poly(A) tract DNA, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| pCC051 | pLX2106 containing PCR-amplified ureR P2 promoter lacking poly(A) tract DNA, ori p15A Cmr | This work |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| MOB998 | 5′-GCATTAAATTAGATGAGC-3′; primer anneals to the 3′ end of P. vulgaris hns | This work |

| MOB999 | 5′-CAACATTTATTTGAGACC-3′; primer anneals to the 5′ end of P. vulgaris hns | This work |

| MOB905 | 5′-TGTTTAGAAAAAATAACAATGG-3′; primer anneals 23 bp upstream of the poly(A) tract DNA preceding the ureR P2 promoter | This work |

| MOB907 | 5′-GATATCGATATTGTTATTGCTCAGCAAC-3′; primer anneals 7 bp downstream from the poly(A) tract DNA preceding the ureR P2 promoter | This work |

| MOB1068 | 5′-AGGGATCCTGGTTAGAAGAAAGTATGTGT-3′a; reverse primer anneals to the 5′ end of ureR | This work |

| MOB1069 | 5′-GAGAATTCTGTTGGGTAGGGTGTGAATA-3′b; primer anneals to the IR of the ureD start codon | This work |

The BamHI restriction site is underlined.

The EcoRI restriction site is underlined.

(A preliminary report of this work has appeared previously [C. Coker and H. L. T. Mobley, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. B-97, 1998]).

ureR promoter expression is derepressed in the absence of hns.

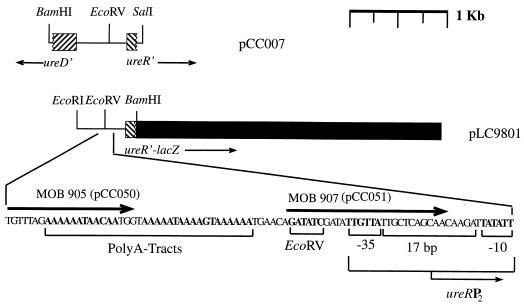

There is a poly(A) tract DNA sequence consisting of A6TA2CA2TGGTA5GA6TGA5 preceding the EcoRV restriction digest site present in the IR (Fig. 1). Immediately downstream (16 bp) of the poly(A) tract sequence is a putative E. coli ς70-like promoter consisting of the DNA sequence TTGTTA–17 bp–TATATT (Fig. 1). Indeed, this corresponds to the strongly inducible P. mirabilis P2 promoter (one of three ureR promoters) identified by D'Orazio et al. by primer extension analysis (3). H-NS is known to bind to poly(A) tracts of DNA which are in phase within the DNA double helix (18) and, in most instances, repress gene expression (1).

FIG. 1.

Cloning strategy used to generate ureR-lacZ fusion constructs. Cloning strategies are described in the text. Thin arrows denote the direction of transcription from ureR and ureD promoter regions; thick arrows represent primers used in PCR amplification procedures (see Table 1). ■, lacZYA reporter genes. Restriction endonuclease sites, poly(A) tracts of DNA, and the −10 and −35 regions comprising the P2 promoter are boldfaced.

To test the hypothesis that H-NS represses ureR promoter P2, a ureR-lacZ reporter plasmid was constructed. Primers MOB1068 and MOB1069 contain internal BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites and anneal, in reverse orientations, 31 bp downstream from the ureR start codon and 100 bp upstream from the ureD start codon, respectively. After digestion with BamHI and EcoRI the ∼1.3-kb PCR DNA fragment was directionally ligated to the protein fusion vector pMLB1034 (31) to form pLC9801. A ureR-lacZ protein fusion product, under ureR promoter control, is predicted to be expressed from this clone.

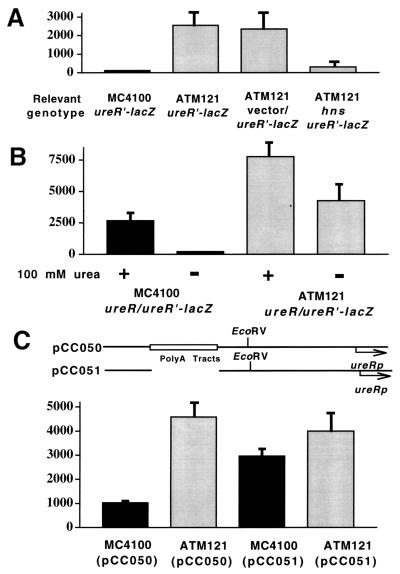

pLC9801 was transformed into E. coli MC4100 and its hns-negative isogenic derivative, ATM121. In the absence of ureR and urea, ureR promoter expression (measured as a function of β-galactosidase activity [21]) was repressed sevenfold (P < 0.0001) in MC4100(pLC9801) compared to ATM121(pLC9801) (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

ureR expression from E. coli MC4100 and its hns::Tn10 isogenic derivative strain ATM121 harboring a ureR-lacZ protein fusion construct. (A) Bacterial cultures were used to measure β-galactosidase activity (Miller units on y axis) (21), after the following E. coli strains were grown to mid-log phase at 37°C: MC4100(pLC9801), ATM121(pLC9801), ATM121(pKHKS303)(pLC9801), and ATM121(pLC9801)(pCC038). pLC9801 encodes a ureR-lacZ operon fusion. pKHKS303 is the plasmid vector used to clone P. mirabilis hns. pCC038 encodes P. mirabilis hns. Error bars represent 2 standard deviations for triplicate samples. The data are representative of at least three experiments. (B) ureR expression from E. coli MC4100 and its hns::Tn10 isogenic derivative strain ATM121 harboring a ureR-lacZ protein fusion recombinant in the presence of ureR. MC4100(pCC002)(pLC9801) and ATM121(pCC002)(pLC9801) were grown as the strains in panel A but in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 100 mM urea. pCC002 encodes ureR, and pLC9801 encodes a ureR-lacZ operon fusion. Error bars represent 2 standard deviations for triplicate samples. The data are representative of at least three experiments. (C) ureR expression from E. coli MC4100 and its hns::Tn10 isogenic derivative strain ATM121 harboring ureR-lacZ operon fusion recombinants either containing or lacking a poly(A) tract DNA sequence. MC4100 (hns+) harboring either pCC050, which contains the poly(A) sequence, or pCC051, which lacks the poly(A) sequence (see Fig. 1 for details) and ATM121 (hns mutant) harboring either pCC050 or pCC051 were grown as the strains in panel A. Error bars represent 2 standard deviations for triplicate samples. The data are representative of six experiments.

P. mirabilis hns was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA using primers MOB998 and MOB999 and Vent DNA polymerase. The plasmid vector pKHKS303 was constructed in our laboratory by PCR amplifying pBCKS using primers B1830 and A1161 and Taq DNA polymerase as previously described (36). The resulting linear pBCKS DNA fragment lacking the ColE1 ori was ligated to a T4 DNA polymerase-treated 888-bp XmnI-HindIII DNA fragment from pACYC184, which encodes the p15A ori. The final recombinant plasmid is compatible with plasmids bearing the ColE1 ori that are not Cmr. PCR amplified hns was ligated to SmaI-digested pKHKS303 to form plasmid pCC037, which was verified by restriction enzyme digestion analysis and subjected to DNA sequencing of the insert fragment in both directions using pBluescriptSK and -KS primers by dideoxy chain termination (30) at the Biopolymer Core Facility at University of Maryland, Baltimore, with an Applied Biosystems model 373A automated DNA sequencer using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit.

The derepression of ureR promoter activity was overcome by in trans complementation with cloned P. mirabilis hns on pCC037 but not by a vector control plasmid. Full repression, compared to MC4100(pLC9801), however, was not observed (Fig. 2A). P. mirabilis hns is predicted to encode a polypeptide product that differs from P. vulgaris H-NS at only one amino acid residue (leucine 115 in P. vulgaris and proline 115 in P. mirabilis) (17). The predicted amino acid sequence is 71% identical to H-NS encoded by E. coli (17). Interestingly, the proline residue at position 115 in P. mirabilis H-NS is conserved in other H-NS polypeptides within the Enterobacteriaceae (1, 17).

A plasmid expressing ureR (pCC002) that is compatible with pLC9801 was constructed in two steps. pΔR10ureD-lacZ (containing intact ureR [11]) was digested with PstI and AluI to release an ∼1.1-kb DNA fragment which was gel purified and ligated to PstI- and EcoRV-digested pBluescriptSK to form pCC001. After digestion of pCC001 with BamHI and HindIII the ∼1.1-kb DNA fragment encoding ureR was ligated directionally to BamHI-HindIII-digested pACYC184 to form pCC002. In this construct the promoter and regulatory elements of ureR have been deleted and ureR is under control of the promoter for the Tcr determinant of pACYC184.

When ureR was provided in trans on plasmid pCC002, ureR promoter expression was inducible by urea in both H-NS+ and H-NS− host backgrounds as expected; however, overall activity was increased in the H-NS− background compared to the H-NS+ background host (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, ureR promoter expression was not significantly different (P = 0.072) in the H-NS+ background when induced by urea compared to expression in the H-NS− background without urea induction (Fig. 2B). Unaccountable factors such as plasmid DNA supercoiling, or other repressors such as the hns analogue stpA (1, 38), could play a role in ureR repression. An hns knockout in P. mirabilis will be valuable in assessing the role of hns in ureR expression; however, attempts to create an hns knockout in P. mirabilis have not been successful. This approach has been hampered due to the nominal size of the open reading frame that encodes hns (405 bp) and the lack of availability of DNA sequences flanking hns.

The poly(A) tract DNA sequence is responsible for ureR repression in an hns-dependent manner.

We hypothesized that H-NS binds to the poly(A) tract DNA sequence preceding the ureR P2 promoter and prevents transcription of ureR. According to this model, we predicted that ureR promoter repression would be relieved in an H-NS+ host if the poly(A) tract DNA was removed.

Operon fusion constructs consisting of the ureR P2 promoter region, either containing or lacking the poly(A) tract DNA sequence preceding the P2 promoter, were constructed in multiple steps. An approximately 0.6-kb DNA fragment consisting of a 492-bp IR flanked by the divergently oriented ureR and ureD promoter regions was isolated from pΔR10ureD-lacZ (11) on a BamHI-NruI restriction digest DNA fragment and ligated to BamHI-EcoRV restriction-digested pBluescriptKS+ to form pCC007 (Fig. 1). PCR products were amplified from pCC007 using Pfu polymerase and primer pairs MOB905/KS and MOB907/KS. The PCR product amplified with the MOB905/KS primers consisted of a 359-bp fragment that included the P2 promoter region preceded by 7 bp, while the PCR product amplified using the MOB907/KS primer pair consisted of a 312-bp fragment that lacked the poly(A) tract region and 6 bp downstream. These products were ligated to the operon fusion vector pLX2106 that was constructed in our laboratory by digesting pRS415 (33) with ScaI and EagI to release an ∼8.0-kb DNA fragment that was gel purified and ligated to EagI- and EcoRV-digested pACYC184. This fusion vector contains a transcriptional terminator upstream from the multiple cloning site used for insertion of exogenous DNA promoter sequences, is Cmr, and is compatible with ColE1 replicons. The resulting recombinant plasmids pCC050 and pCC051 were sequenced to verify the orientation of the insert DNA and to confirm that lacZ would be under ureR P2 promoter control. Recombinant plasmid pCC050 is an operon fusion construct that contains 7 nucleotides upstream from the poly(A) tract DNA and the ureR P2 promoter sequences fused to the β-galactosidase gene (Fig. 1). pCC051 is an isogenic plasmid that lacks the poly(A) tract DNA (Fig. 1).

As shown in Fig. 2C, ureR promoter expression in MC4100(pCC050) was about fourfold (P < 0.0001) less than that in ATM121(pCC050). This pattern of ureR expression was similar to that seen when pLC9801 was used as the reporter construct plasmid in these host strains. In contrast, MC4100 and ATM121 harboring pCC051 [which lacks the poly(A) tract DNA sequence present in pCC050] exhibited similar ureR promoter expression (Fig. 2C).

Poly(A) tracts occurring in DNA have been shown to result in DNA bending which can dampen gene expression (16, 18, 27) and are also known to be binding sites for the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein H-NS (37). H-NS is responsible for repression of virulence gene promoters at the level of transcription in many bacterial genera including Escherichia, Shigella, and Salmonella spp. (1). Importantly, the presence or absence of the poly(A) tracts makes no difference for ureR expression in an H-NS− background. The ureR promoter is derepressed in an H-NS-dependent manner, and this repression is contingent on the presence of a poly(A) tract of DNA upstream from the ureR P2 promoter.

Expression of P. mirabilis urease is derepressed in an hns mutant of E. coli.

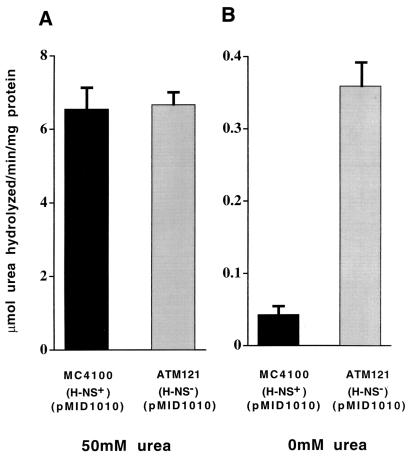

Since UreR is required for transcriptional activation of the P. mirabilis urease gene cluster, we postulated that urease expression would be elevated in an hns mutant host. MC4100 and ATM121 harboring recombinant plasmid pMID1010 (encoding the wild-type P. mirabilis urease gene cluster) produced equivalent amounts of urease (10, 24) when induced with urea (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in the absence of urea, urease activity was significantly greater (8.4-fold; P = 0.0001) in ATM121(pMID1010) compared to the isogenic wild-type strain MC4100(pMID1010), although full urease expression (relative to urea-induced urease expression) was not achieved (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Urease expression from E. coli MC4100(pMID1010) and ATM121(pMID1010) cultured in the presence or absence of urea. E. coli MC4100 and ATM121 harboring pMID1010 (encoding the P. mirabilis urease gene cluster) were grown to late exponential phase in the presence of 50 mM urea (A) or absence of urea (B). Soluble protein (1.0 mg) from bacterial French press lysates was used to measure urease activity in the phenol red spectrophotometric assay. Error bars represent 2 standard deviations for triplicate samples. The data are representative of three experiments. Note different scales in the two panels.

This result emphasizes the fact that full urease expression requires both urea and UreR even in an hns-negative background. Since ureR is significantly expressed in the hns-deficient background in the presence of ureR and absence of urea (Fig. 2A), we propose that the increased urease activity from ATM121(pMID1010) in the absence of urea is due to binding of UreR in a nonspecific manner to the ureD promoter region and spontaneous low-level activation of the urease gene cluster. In the presence of urea, the ureD promoter region is most likely saturated with UreR, present in its transcription activation state; thus, urease activities in H-NS+ and H-NS− backgrounds are comparable. Furthermore, H-NS gene repression can be fully overcome in the presence of an inducer specific for H-NS-repressed genes. Examples include H-NS repression of genes encoding the CFA/I pili of E. coli overcome by the positive activator CfaD (15), repression of CS-1 pili overcome by Rns (25), pap gene repression overcome by PapB (6), and VirF activation of the Shigella virB locus which is repressed by H-NS (35). Interestingly, in H-NS-negative backgrounds, some genes still require the presence of their cognate activator and/or inducer for full expression (P. mirabilis ureR and ureD [this study], Shigella virB [35], and E. coli CS-1 pilus genes [25]) whereas for other genes (E. coli pap [6] and cfa [15] genes) their cognate activator proteins are not required for full expression in the absence of hns.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Public Health Service grant AI23328.

Strain ATM121 was a kind gift from Anthony Maurelli. Plasmid vectors pKHKS303 and pLX2106 were constructed in this laboratory by James Kyle Hendricks and Xin Li, respectively. The ureR-lacZ protein fusion plasmid was constructed by Laurel Courtemanch in this laboratory. We thank Magdelene Spence for excellent technical assistance, Lisa Sadewicz for sequencing expertise, and Joan Slonczewski, Susan R. Heimer, and David J. McGee for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braud A I, Siemienski J. Role of bacterial urease in experimental pyelonephritis. J Bacteriol. 1960;80:171–179. doi: 10.1128/jb.80.2.171-179.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Orazio S E F, Thomas V, Collins C M. Activation of transcription at divergent urea-dependent promoters by the urease gene regulator UreR. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:643–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Orazio S E F, Collins C M. UreR activates transcription at multiple promoters within the plasmid-encoded urease locus of the Enterobacteriaceae. Mol Microbiol. 1995;21:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Orazio S E F, Collins C M. The plasmid-encoded urease gene cluster of the Enterobacteriaceae is positively regulated by UreR, a member of the AraC family of transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3459–3467. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3459-3467.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher S A, Csonka L N. Fine-structure deletion analysis of the transcriptional silencer of the proU operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4508–4513. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4508-4513.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorril R H. The fate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, and Escherichia coli in the mouse kidney. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1965;89:81–88. doi: 10.1002/path.1700890110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith D P, Musher D M, Itin C. Urease: the primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Investig Urol. 1976;13:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith D P. Urease stones. Urol Res. 1979;7:215–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00257208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton-Miller J M T, Gargan R A. Rapid screening for urease inhibitors. Investig Urol. 1979;16:327–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Island M D, Mobley H L T. Proteus mirabilis urease: operon fusion and linker insertion analysis of ure gene organization, regulation, and function. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5653–5660. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5653-5660.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones B D, Lockatell C V, Johnson D E, Warren J W, Mobley H L T. Construction of a urease-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: analysis of virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1120–1123. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1120-1123.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones B D, Mobley H L T. Proteus mirabilis urease: genetic organization, regulation, and expression of structural genes. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3342–3349. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3342-3349.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones B D, Mobley H L T. Genetic and biochemical diversity of ureases of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella species isolated from urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2198–2203. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2198-2203.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordi B J A M, Dagberg B, de Haan L A M, Hamers A M, van der Zeijst V A M, Gaastra W, Uhlin B E. The positive regulator CfaD overcomes the repression mediated by histone-like protein H-NS (H1) in the CFA/I fimbrial operon of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1992;11:2627–2632. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo H S, Wu H M, Crothers D M. DNA bending at adenine-thymine tracts. Nature. 1986;320:501–506. doi: 10.1038/320501a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Teana A, Falconi M, Scarletto V, Lammi M, Pon C L. Characterization of the structural genes for the DNA-binding protein H-NS in Enterobacteriaceae. FEBS Lett. 1989;244:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucht J M, Dersch P, Kempf B, Bremer E. Interactions of the nucleoid-associated DNA binding protein H-NS with the regulatory region of the osmotically controlled proU operon of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6578–6586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maniatis T, Fritsch E, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurelli A T, Sansonetti P J. Identification of a chromosomal gene controlling temperature-regulated expression of Shigella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2820–2824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mobley H L T, Island M D, Hausinger R P. Molecular biology of microbial ureases. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:451–480. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.451-480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mobley H L T, Warren J W. Urease-positive bacteriuria and obstruction of long-term urinary catheters. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2216–2217. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2216-2217.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mobley H L T, Jones B D, Jerse A E. Cloning of urease gene sequences from Providencia stuartii. Infect Immun. 1986;54:161–169. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.161-169.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphree D, Froehlich B, Scott J R. Transcriptional control of genes encoding CS1 pili: negative regulation by a silencer and positive regulation by Rns. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5736–5743. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5736-5743.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson E B, Concaugh E A, Foxall P A, Island M D, Mobley H L T. Proteus mirabilis urease: transcriptional regulation by ureR. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:465–473. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.465-473.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owen-Hughes T A, Pavitt G D, Santos D S, Sidebotham J M, Hulton C S J, Hinton J C D, Higgens C F. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS interacts with curved DNA to influence DNA topology and gene expression. Cell. 1992;71:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90354-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeder T, Scleif R. AraC protein can activate transcription from only one position and when pointed in only one direction. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:205–218. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenstein I, Hamilton-Miller J M T, Brumfitt W. The effect of acetohydroxamic acid on the induction of bacterial ureases. Investig Urol. 1980;18:112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanger R, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapira S K, Chou J, Richard F V, Casadaban M J. New and versatile plasmid vectors for expression of hybrid proteins coded by a cloned gene fused to lacZ gene sequences encoding an enzymatically active carboxy-terminal portion of β-galactosidase. Gene. 1983;25:71–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silhavey T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas V J, Collins C M. Identification of UreR binding sites in the Enterobacteriaceae plasmid-encoded and Proteus mirabilis urease gene operons. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1417–1428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobe T, Yoshikawa M, Mizuno T, Sasakawa C. Transcriptional control of the invasion regulatory gene virB of Shigella flexneri: activation by VirF and repression by H-NS. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6142–6149. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6142-6149.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada H, Yoshida T, Tanaka K I, Sasakawa C, Mizuno T. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli hns gene encoding a DNA-binding protein which preferentially recognizes curved DNA sequences. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:332–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00290685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang A, Rimsky S, Reaben M E, Buc H, Belfort M. Escherichia coli protein analogs StpA and H-NS: regulatory loops, similar and disparate effects on nucleic acid dynamics. EMBO J. 1996;15:1340–1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]