Abstract

This study aims to explore the effect of eco-innovation and renewable energy on carbon dioxide emissions (CDE) for G7 countries. Using regression models, the results reveal that eco-innovation and renewable energy lead to reducing CDE in the presence of governance variables. Additional analysis is conducted to examine whether Hofstede national culture dimensions moderate the nexus of "eco-innovation- carbon emission" and "renewable energy-carbon emission". The results show that individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence dimensions moderate positively the eco-innovation-carbon emission relationship. Moreover, power distance and uncertainty avoidance dimensions moderate the relationship between renewable energy and CDE and help reduce carbon emissions. The outcomes of this study provide new insights and directives for policymakers and regulators. In fact, increased investment in eco-innovation and renewable energy will support the environmental agenda of G7 countries. National cultural dimensions should be taken into consideration to improve awareness of environmental quality. Moreover, the combination of governance indicators plays a key role in environmental sustainability.

Keywords: Eco-innovation, Renewable energy, Culture dimensions, Carbon dioxide emissions, G7 countries

1. Introduction

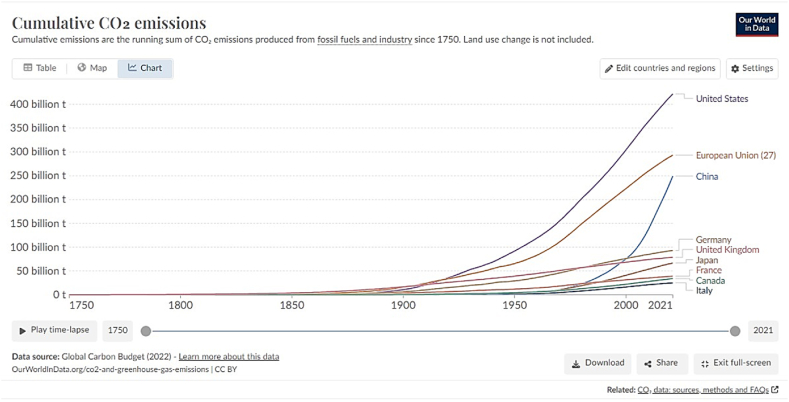

The excessive carbon dioxide emissions (CDE), ecosystem destruction, and the release of pathogens have made the planet an inhospitable place for human life [1]. Throughout the past decade, many countries around the globe are taking serious steps to reduce CDE as it is linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and more principally, SDG 13 climate action. In fact, to achieve SDG 13, global CDE must decrease by 45 % from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050 [2] (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

cumulative CO2 emissions of G7 countries from 1970 to 2021.

Data source: Global Carbon Budget (2022) –OurWorldInData.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions | CC BY

For a long time, non-renewable energy sources have had a significant consequence on global economic growth [3]. While the extreme use of non-renewable energy has increasingly degraded the environment on which human beings depend and hampered the sustainable growth of the global economy [4]. Nations worldwide are actively championing energy conservation, with governments, companies, and scientists increasingly directing their attention towards investments and use of renewable energy (RE) [5]. Besides promoting the environment by reducing CDE, the growth of the RE industry has a key role in economic growth in general and, in particular, it promotes related industries, creates new jobs, alleviates poverty, and serves as an engine to transform macroeconomic development [6,7].

Eco-innovations are innovations that aim to prevent or reduce negative environmental impacts, enhance environmental quality and participate in achieving sustainable development [8,9]. Literature has reflected that investments in eco-innovation, such as research and development, helps companies to contribute to environmental sustainability as environmentally friendly innovations can mitigate CDE [10,11]. Several studies emphasize that eco-innovation is perceived an effective way to decrease pollution and climate degradation [12]. In this regard, Albitar et al. [13], found a positive relation between commitment to climate change and corporate eco-innovation within listed companies on London Stock Exchange. Their research indicates that companies implementing innovative processes that aims to decrease negative environmental impacts, and effectively manage pollution and efficient use of resources, have higher levels of commitment to climate change.

Moreover, Mensah et al. [14], indicated that ecological innovations play significant role in economic growth [15]. It improves company's environmental performance and limits their harmful impacts on the environment, human health and natural resources [15,16]. Eco-innovation's production process leads to produce energy effective activities and consuming fewer resources, thereby decreasing the overuse of natural resources [16,17]. It facilitates the utilization of RE sources [18,19] and assists in managing effectively waste recycling, processing, and management, mitigating climate change and contributes to water sanitation.

Recent studies show that investments in environmental innovations and RE contribute to a sustainable environment in the long term and, therefore, help curb the CDE [19]. Ji et al. [20] show that RE and eco-innovation limit CDE in Austria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain. In China, Chein et al. [18] highlighted the effectiveness of eco-innovation in diminishing CDE. Hordofa et al. [16] found that implementing environmentally friendly innovations contributes significantly to reducing CDE and improving the environment. This corresponds with other studies such as Qureshi et al. [21] in 17 European countries, Fethi and Rahuma [11] in twenty oil-exporting countries, and Balsalobre-Lorente et al. [22] in five European nations. Nevertheless, all the mentioned studies do not focus on G7 countries and ignore the features that characterize each country. In fact, none of them examines the potential effect of cultural dimensions on CDE. Prior studies show that the perception of the need to reduce CDE varies greatly among countries around the world. Their behavior and methods for reducing their CDE varied quite a little [[23], [24], [25]]. In light of this, it is recognized that there may be a connection between cultural aspects and environmental consciousness in communities.

The G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, and the US) are particularly important as most of them have committed to curbing their CDE and reversing global warming by 2050 [1]. G7 countries also emit more greenhouse gases, including CDE, than any other country. The figure number 1 illustrates the cumulative carbon emissions of G7 countries over the years. It shows that CO2 emissions have incredibly increased since the second industrial revolution in 1920s, also recognized as the technological revolution. In that period of time, the modern airline and automobile industries were developed. The figure shows that the United States of America represents the most CO2 emissions country to date: more than 400 billion tones to date. It also shows that the G7 countries have emitted CO2 emissions more than China and the European countries together.

The G7 countries are arguably the most powerful countries, both politically and economically [26]. Focusing on the G7 countries, it is estimated that these countries account for about 31 percent of global emissions [27]. That is why it is essential to consider them as examples of broader implications.

Hence, this research investigates the influence of eco-innovation and RE on CDE within the G7 nations. Additionally, it examines the influence of cultural factors on CDE through supplementary analyses. The study further explores the moderating role of Hofstede's six national cultural dimensions in the connection between eco-innovation and CDE in the initial stage. Subsequently, it explores the same moderating role in the connection between RE and CDE.

The results of using regression models show that eco-innovation and RE lead to a reduction in CDE, especially in the presence of governance variables. Our findings also indicate that individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence positively influence the connection between eco-innovation and CDE. Moreover, the dimensions of power distance and uncertainty avoidance are shown to mitigate the connection between RE and CDE, resulting in a decrease in CDE.

Our findings have the potential to provide valuable insights for regulators and policy-makers, encouraging them to promote and increase investments in environmental quality and RE. Allocating resources towards the development of energy-based technologies, fostering eco-innovation, and establishing infrastructure and markets for RE can effectively contribute to mitigating CDE in G7 countries. Furthermore, there is a need to strengthen cultural dimensions such as long-term orientation, power distance, indulgence, individualism, and uncertainty avoidance, as they have a key moderating role in the connection between RE, eco-innovation, and CDE. Regulators are encouraged to monitor compliance with governance rules for public and private organizations and to improve national legislation or international convergence with governance principles which help to mitigate environmental risks.

The current research offers valuable contributions to the existing literature. First, The G7 countries are committed to decreasing their CDEs by focusing on green energy sources [28]. This is particularly important because the G7 countries account for 30 % of global energy use and 25 % of CDEs [29]. Accordingly, this research differs from previous studies, such as those by Refs. [5,30,31] as it provides valuable insights into the impact of country-level eco-innovation and public investment in RE on CDEs. Second, this research provides insights to the effect of cultural aspects on CDE by using all the six national culture dimensions of Hofstede et al., [32]. It complements prior literature by investigating the moderating role of the cultural aspects on the relationships “eco-innovation-CDE” and “RE-CDE”, which is usually ignored by prior studies.

Third, the findings of this research have important policy implications. They highlight the need for G7 governments to prioritize the development of green innovations that can effectively reduce emissions. It is crucial for these governments to allocate funding for research and development programs that facilitate the creation of new eco-innovative technologies, which in turn promote sustainable development. In addition, policymakers must establish governing policies and regulations that encourage investments in RE sources. This will help generate clean energy and reduce the reliance on fossil fuels, ultimately leading to a decrease in CDEs. Also, policymakers should implement environmental policies aimed at reducing CDEs. One effective strategy is to enforce carbon taxes [30] which incentivize corporations to adopt green innovations and invest in RE. Overall, these policy measures are essential to address the pressing issue of climate change and promote a more sustainable future.

The rest of the work is organized as follows. A review of the literature and the development of hypotheses are presented in Section 2. Data and methods are presented in Section 3. Section 4 presents the findings and comments. The study ends with the conclusion in Section 5.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

As a result of the increasing attention being paid to climate change, there is a wide range of studies addressing the factors that affect environmental quality. Most recent research has focused mainly on stakeholder theory. Businesses that produce too many greenhouse gases are more likely to face criticism from stakeholders [33]. For instance, customers or business partners might not want high-carbon products. In order to produce products with eco-friendly components, businesses subsequently consult external experts and stakeholders when designing new products [34]. According to Keoleian and Menerey [35], businesses utilize life cycle analysis (LCA) to evaluate the risks a product poses from the beginning of the manufacturing process until it is ready for sale.

The Resource-Based View (RBV) paradigm is also mentioned in the most recent research on the elements that influence environmental quality. According to RBV theory, a firm's resources and capabilities are the main drivers of its ability to gain a competitive edge and accomplish its objectives. It emphasizes the worth of a business' valuable, exceptional, unique, and non-replicable resources [36,37]. Moreover, Hart proposed the Natural Resource-Based View (NRBV) theory as an addition to the RBV theory in 1995. The NRBV theory [38] expands the RBV theory to consider environmental factors. The NRBV conceptual framework names "pollution prevention, product stewardship, and sustainable development" as its three strategic competency levels. When businesses recognize how resource waste contributes to environmental damage, lowering pollution becomes a primary priority. To decrease contamination, product stewardship focuses on operating and manufacturing process improvements [38]. Two further goals of sustainable development include encouraging green industry and addressing the problematic connection between economic growth and environmental issues. In this regard, Li et al. [39], reported that economic growth, population density, foreign direct investment and industrial development increased CDE in 285 Chinese cities. Interestingly, innovation facilitated decreasing the emission levels. This is in line with Hao and Chen [40] who underlined that green innovation alongside RE consumption have an impact on decreasing CDE within E7 countries. They argue that green innovation greatly contributes to the economic development of these economies through improving their environmental quality.

Given this perspective, effective pollution reduction strategies should be developed, such as promoting recycling, RE investment, and eco-innovation techniques [41,42].

2.1. Country level eco-innovation- CDE

The existing literature provides a plethora of findings that explore the nexus between eco-innovation and CDE, with some employing different theoretical perspectives to explain this relationship. Within the eco-innovation literature, RBV highlights the significance of a company's resources, skills, knowledge, and competencies in promoting innovation. Investing in research and development, building capabilities, and advancing technology cultivates a culture that prioritises the development of eco-innovative products and processes, and hence effecting the company's sustainable and firm performance [43,44]. Overall, RBV offers a valuable lens for understanding how companies can effectively and efficiently utilize their resources to promote eco-innovation and contribute to sustainable development. On the other hand, stakeholder theory [45] postulates that the different interests of stakeholders are important, indicating that shareholders should not be the sole focus [46]. This theory highlights how different stakeholder groups can pressure companies to accomplish specific environmental goals and encourage the adoption and creation of eco-innovation [21,47,48].

Moreover, scholars have long debated the effectiveness and impact of eco-innovation on mitigating CDE. For example, within the context of G7 countries, Sharif et al. [31] reported that green innovation and green financing promote environmental sustainability through reducing CDEs. Similarly, Olanrewaju et al. [5] examined the impact of eco-innovation and trade openness on CDEs and found that eco-innovation improves environmental quality. Akram et al. [30] noted that environmental innovations have a negative and significant impact on CDEs in both the short and long term, thereby contributing to the achievement of carbon neutrality within G7 countries. Rehman et al. [49] noted that trade openness and foreign direct investment increased CDEs in Germany and Canada, while reducing them in the UK and US.

Furthermore, in a study examining 29 European Union countries, Ostadzad [50] found that innovations help mitigate emissions and improve clean energy advancements. Khurshid et al. [51] reported that environmental policies and green innovations facilitated reducing CDEs in 15 EU countries. Qureshi et al. [21] studied the European eco-innovation index and its impact on CDE through examining companies within 17 European countries. On the country level, eco-innovation index had a significant negative effect on the companies’ directly produced CDE. Further, a negative significant relationship was identified between eco-innovation index and the indirectly produced emissions through the value chain of the 17 European companies. Thereby, their study reflects the significance of eco-innovation in limiting the direct and indirect CDE. Similarly, Balsalobre-Lorente et al [22] reported that energy innovation, natural resources, and renewable electricity consumption had a positive influence on environmental quality in the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, France and Germany. Energy innovation was identified as facilitating the mitigation of CDE.

Moreover, Ji et al. [20], incorporated advanced panel data econometric tools to evaluate the influence of fiscal decentralisation and eco-innovation on CDE in Austria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Switzerland and Spain. Their findings assert that RE and eco-innovation decrease CDE. The use of eco-innovation facilitates a decrease in energy consumption, which in turn decreases fossil fuel demand and consequently reduces CDE [52]. Ji et al. [20], also highlight the importance of investments in environmental innovations as they contribute to establishing a sustainable environment in the long run. In support, Chein et al. [18], denote that eco-innovation, represented by investment in innovation and research and design, is perceived as one of the effective and significant aspects that contribute to diminishing CDE in China.

Correspondingly, Fethi and Rahuma [11] noted that eco-innovation, namely research and development, have a long-term significant and negative effect on CDE within twenty highest refined oil export countries. In a later study, Fethi and Rahuma [53] examined the impact of three eco-innovation indicators, which are research and development, investment and training, on CDE in a number of petroleum companies through using second-generation panel regression econometric techniques. The findings indicate that on the long-term, investment was found to have profound influence on reducing CDE, however, on the short-term training and research and development have profound impact on reducing CDE. More recently, Hordofa et al. [16], found that, eco-innovation, particularly, patents and environmental innovations, and green investment have negative relationship with CDE in China. Their research asserts that implementing environmentally friendly innovations contributes significantly in limiting CDE and hence reflects positively on the environment. This is in accordance with Mensah et al. [54], findings which stressed that trademark and eco-patent, combined, reduced CDE within OECD countries.

The literature reviewed above emphasizes the significant role that innovation has in reducing CDEs. However, some research argue that innovation increases CDEs [24,55,56]. They advocate that higher innovation increases economic activities and energy use which in turn results in increasing CDEs. Wang et al. [57], examined the effect of foreign direct investment and technological innovations on CDEs. Their findings showed that foreign direct investment decreased CDEs, while the impact of innovation varied depending on the different quantiles, either increasing or decreasing CDEs.

In addition, Dauda et al. [58], Li et al. [59], Mensah et al. [14], and Zhang and Chen [60] reported that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between innovations and emissions. They highlight that in the initial stages, innovation has a scale effect that increases emissions. However, later on, innovation generates enough technique impact over the scale and hence facilitates reducing the emissions. These various findings underline the importance of ascertaining the impact of eco-innovation on CDEs in G7 countries, which this research seeks to do. Accordingly, we propose the first hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis 1

There is a negative association between country-level eco-innovation and CDE

2.2. Public investment in RE and CDE

The primary drivers of climate change, according to Yu et al. [61] and Sarkodie and Strezov [62], are emissions resulting from burning fossil fuels. The third stage of strategic capabilities for sustainable development is studied in recent literature using the NRBV theory [38].The NRBV theory emphasizes the value of green business, particularly the contribution that investments in eco-friendly goods and RE sources provide to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. This has led to a rapid increase in RE investment and power generation. Global investments in RE increased by 9.9 times to $495 billion between 2005 and 2022 (Bloomberg, 2023).

Wu and Song [63] used AMG analysis of panel data for BRI nations from 2005 to 2018 to investigate the effect of public spending and RE investment on the reduction of CDE. The authors looked at the connections between R&D, GDP growth, FDI (foreign direct investment), CDE, green finance, and the development of RE sources. According to the research, there is a link between rising GDP, public spending, FDI, and the development of RE sources. On the other side, pollution impedes the development of RE.

As a substitute for non-RE, RE has the potential to significantly lower CDE from burning coal, oil, and natural gas. Numerous studies that have been conducted using sample data from various regions and nations have proven this.

Single-country datasets have been analyzed by numerous studies. Hao [64] looks at the industrial and agricultural perspectives on the long- and short-term links between the use of RE, output, export, and CDE in the case of China. The study confirmed that, while the use of RE has a positive impact on the environment, output and exports have negative effects, and that there is a two-way causal relationship over the long run between the use of RE, output, exports, and CDE.

For the United States, real GDP, nuclear, renewable, and CDE are examined by Menyah and Wolde-Rufael [65]. The Granger causality test did not reveal a relationship between the use of RE and CDE, but it revealed a one-way relationship between the use of nuclear power and CDE.

Similarly, in Pakistan, Mirza and Kanwal [66] examined data on total energy consumption. They discovered a two-way, long-term causal link between overall energy use, economic growth, and CDE. Granger causality was used by Shahzad et al. [67] to demonstrate a positive correlation between energy use and CDE.

Macro panel data has been utilized in other research to investigate this relationship. More recently, Saidi and Omri [6] used the FMOLS and VECM estimating methods to analyze the effects of RE consumption on economic development and CDE for a panel of 15 nations that were large users of RE from 1990 to 2014. The FMOLS technique's findings demonstrate how effectively RE may boost economic growth and reduce CDE. The FMOLS method's findings, however, indicate a short-term bidirectional causal relationship between CDE and RE rather than a long-term causal relationship between CDE and RE.

For a panel of 97 nations between 1995 and 2015, Chen et al. [7] looked at the nonlinear effects of economic growth, renewable and non-RE use, and per capita CDE. When countries exceed a specific RE threshold, the results of a strong dynamic panel threshold model demonstrate that an increase in per capita RE use has a considerable negative impact on per capita CDE growth. This result is robust to the use of other proxies for RE use and holds mostly for industrialized countries and nations with stronger institutions.

The long-term relationship between CDE, RE, and energy efficiency is examined by Ponce and Khan [68] in nine developed nations from 1995 to 2019. The findings support the existence of a long-term equilibrium connection for developed European countries but not for developed non-European countries. It was discovered that there was a negative relationship between RE, energy efficiency, and CDE. Every 1 % increase in RE consumption is linked to a 0.03 % drop in CDE in developed European nations. Similar to this, Ito [69] applied the GMM model to a panel of 42 developing nations and discovered that RE consumption lowers CDE.

Additionally, for a panel of seven Central American nations between 1980 and 2010, Apergis and Payne [70] examined the relationship between RE, real GDP, real oil prices, CDE, and real coal prices. The Granger causality's findings demonstrated a long-term positive and significant cointegrated link.

Autoregression (SVAR) was used by Silva et al. [71] to examine the relationship between RE, real GDP, and CDE for the US, Denmark, Portugal, and Spain. Their findings demonstrate that rising RE use is associated with a decline in per capita CDE. Contrarily, Tiwari [72] demonstrates that non-RE raises CDE and has a negative impact on GDP growth for countries in Europe and Eurasia. Using information from OECD nations from 1980 to 2011, Shafiei and Salim [73] explore the causes of CDE. According to the STIRPAT model's findings, although RE reduces CDE, non-RE causes them to rise.

In the G7 context, Olanrewaju et al. [5] investigated the impact of RE and non-RE use on environmental damage using a variety of econometric techniques. The results of long-term estimators proved that the use of non-RE contributes significantly to the increase of CDEs, while the increase of RE consumption leads to better environmental quality. Usman [74] examines the contribution of public spending on RE and green energy technology to the lowering of CDE for the G7 countries using data from 1990 to 2017. The results of the MM-QR regression demonstrate that investing in RE and green energy technology has a mixed and adverse impact on CDE. The quantile distribution of CDE is particularly negatively and inconsistently impacted by the interaction term. According to the findings, the amount that countries invest in green energy technologies determines how much RE exerts decreasing pressure on CDE. Additionally, in nations with lower CDE, the interaction term has a bigger influence.

According to the aforementioned literature, we predict that for G7 countries, an increase in public RE spending will result in a decrease in CDE, and we recommend the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2

There is a negative association between country-level public investment in RE and CDE

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Sample selection

The sample of this study includes the G7 countries: Canada, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The G7 governments endorse the acceleration of the transition towards clean and RE. The economic activity of G7 countries represents 40 % of the total world activity, and they are well-placed to be the first movers in mitigating CDE. The empirical study covers the period 2000–2019. The time period was selected based on data availability. Data were extracted from the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

3.2. Variable definitions and sources

3.2.1. The dependent variable

The dependent variable in our study is the CDE of G7 countries, measured in metric tons. The consumption of solid, liquid, and gas fuels and gas flaring induce CDE. In the context of G7 countries, previous research has used the same measure to explore their experience with CDE [1,75,76].

3.2.2. The independent variables

RE is measured in millions of USD in public investment in RE. The data was extracted from IRENA. Following recent studies [77,78], this study includes this variable to denote the impact of RE on CDE.

Based on prior research [79,80], we used environment-related technologies and patents in terms of all technologies to measure eco-innovation. This variable is extracted from the OECD database.

3.2.3. Moderating variable: Hofstede's cultural dimensions

The moderating effect of Hofstede's cultural dimensions is measured in six dimensions. Power distance measures the acceptance by less powerful members or institutions (country level) of an unequal distribution of power. Individualism denotes the extent to which societies care about themselves. The masculinity dimension measures how society is driven by success and competition. Uncertainty avoidance demonstrates how society deals with ambiguity and incertitude. Long-term orientation shows the extent of adopting a pragmatic approach to build for the future while keeping ties with their past. Indulgence measures the extent of gratification of the needs to have fun and enjoy. Prior research studied the impact of Hofstede's cultural dimensions on CDE [23,81].

3.2.4. Control variables

We use the following variables: governance, financial development, and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The governance index was extracted from the World Bank database. Kaufmann et al. [82] defined six dimensions of governance (see Table 1) to assess the quality of governance. These dimensions encompass different aspects of governance, related particularly to the ability of governments to set up sound policies, control corruption, and how citizens are involved in the decision-making process. Prior studies investigated the effect of governance quality on CDE by using Kaufmann governance dimensions [83,84]. Financial development and GDP have been considered control variables in many studies [21,85].

Table 1.

Variables definitions and measurements.

| Variables | Definitions and Measurements | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 emission (CDE) | is measured by the natural logarithm of carbon dioxide emissions. | World Bank |

| Renewable energy (RE) | Amount of public investment in RE in million USD | IRENA |

| Eco-innovation (ECI) | patents on environment-related technologies as a percentage of the total patents on all technologies | OECD |

| Hofstede Culture dimensions | Hofstede insights | |

| Power distance (POWD) | -High index of Power distance denotes that people do not tend to distribute power and prefer following a hierarchy. | |

| Individualism (INDIV) | - A high Individualism score indicates that individuals do not have close ties. | https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool |

| Masculinity (MASC) | -A high degree of Masculinity shows that society is more oriented towards success and achievement. | |

| Uncertainty-avoidance (UNCA) | -A high uncertainty avoidance explains how society is ready to accept and deal with ambiguous plans. | |

| Long-term orientation (LTOR) | - High long-term orientation demonstrates a willingness to adapt to circumstances. | |

| Indulgence (INDU) | - High indulgence shows how societies are focused on their happiness. | |

| Governance Index (GOV) | - Overall index | World Bank |

| - corruption control (COCT) | -Corruption control: measures how the distortion of public power leads to a private gain. | |

| - effectiveness of the government (EFF) | - Effectiveness of the government: this index measures the commitment of the government to provide high-quality public services. | |

| - political stability (POLS) | - Political stability: measures how countries experience violence and terrorism. | |

| - regulatory quality (REGQ) | - Regulatory quality: measures the ability of the government to build consistent policies that enhance development | |

| - rule of law (RUL) | - Rule of law: measures the extent to which agents respect society's rules | |

| - voice and accountability (VAAC) | - Voice and accountability: measures how society can express their opinions, participate in the selection of their government, and the freedom in many areas: media, association … | |

| Financial development (FID) | Domestic credit to private sector (percentage of GDP) | World Bank |

| Gross Domestic product (GDP) | The natural logarithm of GDP per capita | World Bank |

Table 1 presents the variables of this study, definitions and measurements, and sources.

3.3. Empirical model

To explore the impact of eco-innovation and RE on the CDE, we use a multivariate regression model using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). Different models were used to test the direct impact of ECI and RE on CDE in the presence of governance variables. The empirical models test the impact of the aggregate and individual governance indicators separately. The variables used in this study are defined in Table 1.

| CDEit = α1ECIit + α2 REit + α3⅀ GOV dimensionsit + α4⅀control variablesit+ ε_it | [1] |

In Model 2, we replace the GOV dimensions with the Governance Index (GOV indexit):

| CDEit = α1ECIit + α2 REit+ α3⅀ GOV indexit + α4⅀control variablesit+ ε_it | [2] |

We run the analysis by including ECI and RE separately (Table 4, models 1, 2, 3,4) and then include both ECI and RE in the same model (Table 4, model 5).

Table 4.

The impact of Eco and RE on CDE, using governance index and each governance dimension.

| VARIABLES | (1) CDE | (2) CDE | (3) CDE | (4) CDE | (5) CDE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECI | −0.142*** (0.0172) | −0.127*** (0.0201) | −0.108** (0.0143) | ||

| RE | −0.0547*** (0.0192) | −0.0499** (0.0199) | −0.0328** (0.01921) | ||

| COCT | −0.587** (0.244) | −0.865*** (0.306) | −0.588*** (0.0791) | ||

| EFF | 0.268 (0.244) | 0.784*** (0.288) | 0.0159*** (0.00536) | ||

| POLS | −0.340*** (0.126) | −0.417** (0.161) | −0.307*** (0.00450) | ||

| REGQ | −1.154*** (0.248) | −0.781** (0.306) | 0.282*** (0.00376) | ||

| RUL | 2.033*** (0.309) | 1.797*** (0.375) | 0.0532*** (0.00134) | ||

| VAAC | −0.190 (0.304) | −0.632* (0.369) | 0.400*** (0.00572) | ||

| GOV | −0.0608*** (0.00911) | −0.0665*** (0.0105) | −0.0109*** (0.00180) | ||

| FDEV | 0.0171*** (0.00109) | 0.0187*** (0.00130) | 0.0105*** (0.00118) | 0.0123*** (0.00134) | 0.209*** (0.00273) |

| GDP | 1.150*** (0.245) | 0.334 (0.269) | 2.486*** (0.271) | 1.897*** (0.291) | −2.99*** (0.739) |

| Constant | 0.355 (2.606) | 7.519** (2.969) | −7.690*** (2.502) | −2.376 (2.679) | −3.356 (1.129) |

| Observations | 121 | 118 | 128 | 125 | 118 |

| R-squared | 0.881 | 0.830 | 0.786 | 0.734 | 0.714 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum of all variables used in the study. The mean value of ln (CDE) is 13.48; it ranges between 12.61 and 15.56. As per the ln (CDE) variable, the mean is 13.489, and it reaches a maximum of 15.569. The mean value of public investment in RE is equal to 365.454 million dollars; it reaches a maximum of 2366 million dollars. Eco-innovation, measured using environment-related technologies and patents in terms of all technologies, has a mean value of 10.701, and it ranges between 5.69 and 15.7. Financial development varies between 60.35 and 208.815. The average GDP per capita is around 8236.489 dollars. The mean of the governance index is 82.128. The index ranges between 66.656 and 89.43. The score of Hofstede culture dimensions has the highest mean (74.286) for the individualism dimension; the lowest mean is associated with the power distance dimension. Masculinity and uncertainty avoidance have roughly comparable mean values (respectively, 64.857 and 63.857). The masculinity dimension is very high in some countries and reaches 95. The variation in long-term orientation is from 26 to 88. The indulgence dimension score has a mean value of 52.143, and it reaches a maximum of 69. The standard deviation of culture dimensions is low; the values are dispersed from the mean.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDE | 140 | 13.488 | 0.904 | 12.613 | 15.569 |

| RE | 137 | 365.454 | 509.244 | 0.005 | 2366 |

| ECI | 140 | 10.701 | 2.415 | 5.69 | 15.7 |

| FDEV | 128 | 126.522 | 41.749 | 60.35 | 208.815 |

| GDP | 140 | 10.551 | 0.205 | 10.169 | 11.077 |

| GOV | 140 | 82.128 | 5.17 | 66.656 | 89.43 |

| COCT | 133 | 1.432 | 0.535 | 0.006 | 2.072 |

| POLS | 133 | 0.667 | 0.345 | −0.233 | 1.411 |

| REGQ | 133 | 1.337 | 0.331 | 0.495 | 1.885 |

| VAAC | 133 | 0.150 | 0.023 | 0.118 | 0.202 |

| EFF | 133 | 1.436 | 0.417 | 0.191 | 1.924 |

| RUL | 133 | 1.420 | 0.423 | 0.264 | 1.886 |

| POWD | 140 | 45.857 | 11.322 | 35 | 68 |

| INDIV | 140 | 74.286 | 14.17 | 46 | 91 |

| MASC | 140 | 64.857 | 15.12 | 43 | 95 |

| UNCA | 140 | 63.857 | 20.111 | 35 | 92 |

| LTOR | 140 | 58.286 | 21.172 | 26 | 88 |

| INDU | 140 | 52.143 | 14.909 | 30 | 69 |

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation matrix for dependent and the independent variables. The table shows the correlation between the dependent variable (CDE) and independent variables. The correlation between control variables is also examined. As reported in the results, all the correlation coefficients are lower than the standard threshold [86,87]; hence, there is no multicollinearity problem.

Table 3.

Matrix of correlations.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CDE | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (2) ECI | −0.172 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (3) RE | −0.108 | 0.515 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (4) FDEV | −0.291 | 0.379 | 0.119 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (5) GDP | 0.448 | 0.516 | 0.482 | 0.320 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (6) GOV | −0.291 | 0.379 | 0.119 | 1.000 | 0.320 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (7) POWD | −0.206 | −0.038 | −0.098 | −0.254 | −0.288 | −0.254 | 1.000 | |||||

| (8) INDIV | 0.381 | −0.193 | −0.221 | 0.518 | 0.318 | 0.518 | −0.452 | 1.000 | ||||

| (9) MASC | 0.048 | −0.025 | 0.223 | −0.630 | −0.133 | −0.630 | −0.119 | −0.599 | 1.000 | |||

| (10) UNCA | −0.319 | 0.087 | 0.089 | −0.449 | −0.340 | −0.449 | 0.806 | −0.842 | 0.308 | 1.000 | ||

| (11) LTOR | −0.562 | 0.233 | 0.263 | −0.178 | −0.379 | −0.178 | 0.301 | −0.869 | 0.540 | 0.726 | 1.000 | |

| (12) INDU | 0.433 | −0.065 | −0.071 | 0.230 | 0.348 | 0.230 | −0.431 | 0.644 | −0.366 | −0.791 | −0.761 | 1.000 |

4.2. Regression results

Table (4) presents the regression results of the impact of ECI and RE on CDE. The estimation was based on four models. Model (1) incorporates ECI and governance in six related dimensions. Model (2) includes RE and governance dimensions. Model (3) tests the effect of eco-innovation on CDE in the presence of the overall governance score. Model (4) includes RE and a governance score.

Based on the results of model (1), ECI variable has a significant and negative sign. Thus, eco-innovation contributes to the reduction of CDE. Environmental technologies and patents in terms of technologies enhance environmental quality and promote sustainability [18]. Energy consumption can be controlled by the use of technologies that aim to produce clean production and a green environment. Churchill et al. [88], found the same result in the context of G7 countries; the authors used research and development as a proxy for eco-innovation. In the same vein, Akram et al. [30], confirmed our findings for G7 countries and claimed that ECI, as a technological approach, contributes to curbing CDE. Moreover, Ibrahim et al. [89], stated that ECI is the pathway to the neutralization of CDE and environmental sustainability in G7 economies. In the OECD context, Bigerna et al. [90], highlighted the importance of ECI as the primary inhibitor factor for CDE. The authors consider that environmentally-related technologies are the main contributors to the sustainable growth of nations. The coefficients of governance dimensions are statistically significant and negative for control of corruption, political stability and lack of violence, and regulatory quality. High control of corruption induces less environmental damage and prevents the deviations from sustainability directions. Corruption related to the distortion of environmental regulations may be advantageous for some groups and allow them to not comply with CDE rules. High political stability reflects the existence of a strong governance system able to reinforce compliance with environmental rules [91]. The quality of environmental regulations in terms of clarity and detailed descriptions helps fulfil the obligations. Governments should enact clear guidelines related to fees, permits, and licences.

However, the results indicate that the rule of law dimension increases CDE. The existence of loopholes in laws allows some companies to escape compliance without being accused of violations. Moreover, the lack of a system or mechanism to enforce business contracts justifies why companies do not abide by some clauses of the contract. In other cases, when rules are below the optimal level or the costs of enforcement are high, institution quality will decline [92].

Regarding model (2), RE variable is negative and significant. High public investment in RE helps G7 countries curb CDE. Investment in clean energy projects is more effective in CDE abating agenda [93,94]. Erdogan et al. [95], concluded that G7 nations should increase their investment in RE to curb their CDE and achieve CDE neutralization. The results of the governance dimensions impact on CDE of model (1) have also been proved for model 2. The only difference resides in the significance of the dimension of voice & accountability for model (2). Countries with higher voice & accountability have reduced levels of CDE. The citizens ‘freedoms did not prevent them from assuming responsibilities towards a sustainable environment.

ECI variable remains significant in model (3), and the same effect is also proven. The governance index is also negative and significant. When comparing the results of models (1) and (3), the effect of governance is more pertinent when testing the six dimensions separately. The overall score of governance has a slight effect on CDE.

Model (4) results confirm the findings of the model (2) for RE variable. Concerning the governance index, the coefficient estimate is negligible compared to the results of the six governance dimensions in model (2).

FDEV is associated positively and significantly with CDE. High levels of financial development increase CDE and then contribute to the degradation of the environment in G7 countries. This finding is confirmed by other researchers in other contexts [ [96,97]].Financial development was considered a determinant of high CDE as it leads to growth in national income which can result in high consumption of CDE [98]. The financial development pattern in G7 nations does not promote environmental sustainability.

The growth in GDP stimulates CDE. Economic growth is heavily associated with energy emissions; the acceleration of economic activity produces more energy consumption and then more CDE. Ahmad et al. [99] considered the GDP indicator as a driving force for CDE variations.

Model (5) results confirm the same sign of ECI and RE displayed for models (1,2,3,4) where, they were regressed separately. Ibrahim et al. [100] confirmed our finding and stated that ECI and RE are the main channels towards achieving environmental sustainability. Usman [74] concluded that RE and ECI mitigated CDE in G7 countries during the period 1990–2017. However, the effect of the REGQ variable becomes positive when regressing ECI and RE in the same model. The investment in RE and using environmentally friendly technologies reflects the willingness of governments to set up policies that promote sustainable development. Surprisingly, the effect of GDP is negative in model 5. Although GDP was associated positively with CDE, Khalfaoui et al. [101] corroborated our finding and explained that the implementation of green technologies reduces CDE during economic growth.

4.3. Additional analysis

In this section, we conduct additional analyses to better understand how G7 countries deal with CDE. In fact, there is a great heterogeneity between nations around the world in the way the necessity of reducing their CDE is viewed. There are quite a few differences in their manners and approaches toward curbing their CDE. Liu et al. [102] show that the decline in CDE varies by country, culture, and region. Various countries, including the United States, reported a 7.6 % decline in CDE, India a 12.7 % decline, and the UK a 19.3 % decline, while China saw only a small change of 1.4 %. Liu et al. [102] also show that the manufacturing industry lost 5.5 % of its CDE, resulting in a 29 % decrease in total global CDE. Industrial CDE fell by 39 % in China and 33 % in India. A reduction in air and land transport also reduced CDE by 18.6 %, and in the first half of 2020, the authors observed a decrease of 43 % [102]. Such disparities could be attributed to country cultures [23,25]. Indeed, the social context, such as a community's environmental orientation, is significantly shaped by national culture. Therefore, it is acknowledged that there is a possible link between cultural elements and environmental consciousness in communities [23,25,102]

In Hofstede's 2011 paper, culture refers to "the collective mental programming of the human mind that distinguishes one group of people from another." Honesty, trust in authority, trust in people, pride, relationships with nature and the world, relationships with others, independence, uncertainty avoidance, and orientation in time and space represent characteristics that shape the culture of a country and can influence the economic activities of people [103]. More specifically, Hofstede et al. [104] distinguish six aspects of national culture. This includes (1) individualism and collectivism, (2) distance between high and low power, (3) masculinity and femininity, and (4) long-term and short-term orientation. (5) indulgence vs. restraint; (6) high and low risk Each dimension ranks a nation's culture on a scale of 0–100.

National culture is a key characteristic of a nation that can provide a basis for engagement in the reduction of CDE [25]. In fact, global environmental policies need to take national cultural aspects into account when designing policies to avoid potential conflicts between policies and target groups. Although RE, eco-innovation, and CDE represent a center of interest globally, there is little evidence of whether and how national culture can moderate the relationships between them. The current study conducts an additional analysis to provide insight into the relationships between Hofstede et al. [104] six cultural dimensions as a potential moderating variable and the “RE, eco-innovation, and CDE” association. In fact, we examine the moderating role of the six national culture dimensions of Hofstede on the relation between eco-innovation and CDE in the first stage. Then, the same moderating effect is explored for the relation between RE and CDE in a second stage.

- First stage of estimation: Moderating effect of culture dimensions on ECI

| CDEit (1) = α1ECIit + α2POWDit + α3ECIit* POWDit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (2) = α1ECOit + α2INDIVit + α3ECIit* INDIVit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (3) = α1ECOit + α2MASCit + α3ECIit*MASCit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (4) = α1ECOit + α2 UNCAit + α3ECIit*UNCAit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (5) = α1ECOit + α2LTORit + α3ECIit*LTORit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (6) = α1ECOit + α2INDUit + α3ECIit*INDUit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

-

-

Second stage of estimation: Moderating effect of culture dimensions on RE

| CDEit (1) = α1 RE it + α2 POWDit + α3 RE it* POWDit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (2) = α1 RE it + α2INDIVit + α3 RE it* INDIVit+ α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (3) = α1 REit + α2MASCit + α3 RE it*MASCit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

| CDEit (4) = α1 RE it + α2UNCA it + α3 RE it*UNCAit + α4⅀control variablesit + ε_it |

| CDEit (5) = α1 RE it + α2LTORit + α3 RE it*LTORit + α4⅀control variablesit + ε_it |

| CDEit (6) = α1 RE it + α2INDUit + α3 RE it*INDUit + α4⅀control variablesit + εit |

Where i represents country, and ε_ is the associated error.

Table 5A and 5B displays the results of the moderating role of culture on the relationship ECI- CDE. Each regression model includes one Hofstede culture dimension as a moderating variable. The global index of governance is used in this model. R-squared is superior to 0.79 for the six estimation models. Then, the model is globally significant, and the independent variables explain perfectly the dependent variable. ECI, when tested separately, is significant for all estimated models except the estimated model (6). The sign of ECI is negative for five estimated coefficients. However, it is positive and significant in the presence of the indulgence dimension. Individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence dimensions, as moderating variables on ECI, have contributed to the reduction of CDE. Nations with high long-term orientation are more focused on future growth and change. The long-term perspective is associated with great interest in using innovative technologies to achieve a sustainable environment. G7 nations are driven by long-term goals such as reducing CDE and maintaining environmental quality [23,81] (see Table 6A, Table 6B).

Table 5A.

The moderating role of culture Dimensions on ECI.

| VARIABLES | (1) CDE | (2) CDE | (3) CDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECI | −0.123* (0.0628) | 0.359***(0.0964) | −0.287*** (0.0740) |

| POWD | −0.00834 (0.0156) | ||

| ECI*POWD | −0.00000912 (0.00132) | ||

| INDIV | 0.0780*** (0.0139) | ||

| ECI*INDIV | −0.00503*** (0.00118) | ||

| MASC | −0.0475*** (0.0133) | ||

| ECI*MASC | 0.00302** (0.00116) | ||

| FDEV | 0.00980*** (0.00129) | 0.00884*** (0.00106) | 0.0119*** (0.00112) |

| GDP | 2.431*** (0.271) | 1.768*** (0.256) | 2.346*** (0.251) |

| GOV | −0.0677*** (0.00997) | −0.112*** (0.0113) | −0.0865*** (0.0102) |

| Constant | −6.146** (2.703) | −2.733 (2.536) | −1.562 (2.635) |

| Observations | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| R-squared | 0.792 | 0.846 | 0.822 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 5B.

The moderating role of culture Dimensions on ECI.

| VARIABLES | (4) CDE | (5) CDE | (6) CDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECI | −0.172*** (0.0551) | −0.229*** (0.0482) | 0.000472 (0.0629) |

| UNCA | −0.0229** (0.00940) | ||

| ECI*UNCA | 0.00131 (0.000814) | ||

| ECI | |||

| LTOR | 0.0454*** (0.00872) | ||

| ECI*LTOR | −0.00309*** (0.000763) | ||

| INDU | 0.0310** (0.0124) | ||

| ECI*INDU | −0.00202* (0.00116) | ||

| FDEV | 0.00798*** (0.00141) | 0.00958*** (0.00108) | 0.00763*** (0.00173) |

| GDP | 2.375*** (0.266) | 1.651*** (0.272) | 2.473*** (0.264) |

| GOV | −0.0898*** (0.0129) | −0.0781*** (0.00859) | −0.0809*** (0.0122) |

| Constant | −2.767 (2.863) | 4.447(2.905) | −7.390*** (2.560) |

| Observations | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| R-squared | 0.803 | 0.840 | 0.801 |

Table 6A.

The moderating role of culture dimensions on RE.

| VARIABLES | (1) CDE | (2) CDE | (3) CDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| RE | 0.194** (0.0814) | 0.279* (0.142) | 0.0925 (0.0992) |

| POWD | 0.0150 (0.00930) | ||

| RE*POWD | −0.00520*** (0.00173) | ||

| INDIV | 0.0496*** (0.0114) | ||

| RE*INDIV | −0.00272 (0.00175) | ||

| MASC | −0.0103 (0.00773) | ||

| RE*MASC | −0.00167 (0.00148) | ||

| FDEV | 0.0128*** (0.00146) | 0.00672*** (0.00133) | 0.0132*** (0.00125) |

| GDP | 1.762*** (0.278) | 1.328*** (0.241) | 1.752*** (0.273) |

| GOV | −0.0712*** (0.0106) | −0.130*** (0.0113) | −0.0999*** (0.0119) |

| Constant | −1.342 (2.668) | 5.267** (2.427) | 2.330 (2.653) |

| Observations | 125 | 125 | 125 |

| R-squared | 0.764 | 0.835 | 0.778 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 6B.

The moderating role of culture dimensions on RE.

| VARIABLES | (4) CDE | (5) CDE | (6) CDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| RE | 0.136** (0.0641) | 0.0434 (0.0529) | −0.0971* (0.0551) |

| UNCA | −0.00425 (0.00564) | ||

| RE*UNCA | −0.00217** (0.000950) | ||

| LTOR | −0.0220*** (0.00575) | ||

| RE*LTOR | 0.000359 (0.000920) | ||

| INDU | 0.0137** (0.00602) | ||

| RE*INDU | 0.00170 (0.00112) | ||

| FDEV | 0.00878*** (0.00170) | 0.00762*** (0.00128) | 0.00610*** (0.00205) |

| GDP | 1.684*** (0.271) | 1.006*** (0.268) | 1.876*** (0.284) |

| GOV | −0.103*** (0.0130) | −0.0875*** (0.00910) | −0.0990*** (0.0131) |

| Constant | 3.425 (2.716) | 10.16*** (2.795) | 0.437 (2.713) |

| Observations | 125 | 125 | 125 |

| R-squared | 0.783 | 0.822 | 0.766 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The individualism dimension reflects how people make personal decisions and need more autonomy. The individualism dimension supports the innovation capacity of nations [9,105]. In the G7 context, societies with high levels of individualism are expected to take environmental initiatives more seriously. However, in highly collectivist societies, unethical practices may result from favoring in-groups at the expense of outgroups [106]. Therefore, the ethical sensitivity to protecting the environment and reducing the consumption of carbon dioxide will be low. Individual behaviours and practices damage the environment. Then, individual decisions play a major role in shaping environmental policies and reducing the CDE.

The indulgence dimension has been associated with high energy consumption [23,81]. This association is based on the premise that indulgent nations focus on the enjoyment of life, and spend their money to fulfil their personal desires [104]. Thus, they are expected to use more resources and damage the environment as their spending is not controlled. Our study confirms this finding in the context of G7 countries for the variable indulgence. However, the use of the indulgence dimension as a moderating variable contradicts this idea and demonstrates that the indulgence dimension stimulates innovation and lessens the CDE. People of indulgent cultures focus on enjoying their lives and doing the best things; their innovative capacity and creativity are enhanced. The happiness and joy emotions help people create an awareness of health and environmental quality, and they tend to have control over their lives to maintain their happiness.

Concerning the masculinity dimension, our finding contradicts previous results and assumptions ([107], [108], [25]), masculinity has a negative and significant effect on CDE in G7 countries. Therefore, masculinity orientation improves environmental quality and mitigates environmental damage. Masculine G7 societies are not only driven by materialism and economic growth; they also take into consideration environmental issues and are inclined to implement policies to protect the environment. However, the moderating role of the masculinity dimension on eco-innovation leads to higher levels of CDE. Therefore, masculinity does not boost innovation oriented to environmental technologies [109].

Governance reduces CDE; this finding is confirmed for all models. Moreover, FDEV and GDP variables are also significant and positive for all models. The results confirm the findings of Table 4.

4.3.1. The moderating effect of culture dimensions on RE

Table (6) displays the results of the moderating role of culture on the relationship between RE and CDE. RE variable is associated positively and significantly with CDE for all models except for model 6. The investment in RE decreases the CDE only with the control of the indulgence dimension. Indulgent societies are known to be optimistic and willing to use new options to increase their satisfaction. They control their lifestyles and use alternatives to enjoy a high-quality environment. Power distance does not have any significant impact on CDE. However, its moderating effect is negative and significant. High power distance levels lead to lower CDE and promote sustainable initiatives. In some situations, high power distance alleviates conflicts by reducing the time to reach a consensus and helping to take immediate actions to benefit from environmental opportunities. This result confirms the findings of Shortall and Kharrazi [110]. The uncertainty avoidance dimension moderates the relationship RE- CDE and contributes to lowering CDE. With a high avoidance score of uncertainty, societies tend to avoid ambiguity, and unclear situations, or any changes. However, they can embrace new practices or technologies that have been proven efficient [111]. The acceptance and validation of new practices may take time, but the urgent global need to achieve sustainability goals accelerates the pace of taking environmental actions. Thus, G7 societies, scoring highly for the uncertainty avoidance dimension, have to answer the global calls for sustainability and the need to use RE to reduce the CDE.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

The aim of this paper was to explore the impact of renewable energy and eco-innovation on carbon dioxide emissions in G7 countries, an understudied and unique context. The research covers the 2000–2019 period. All data were extracted from the World Bank, OECD, and IRENA.

In the first stage, the empirical analysis explores the role of ECI and public investment in RE in the reduction of CDE in the presence of governance variables (e.g., the overall index and the six related dimensions). The results of the estimation reveal that CDE in G7 countries is reduced by investing in RE and using environment-related technologies. Therefore, the theoretical assumptions are confirmed. The effect of governance is more observed when testing the six dimensions separately. The overall index did not properly highlight the role of governance in mitigating CDE.

Then, we developed an additional analysis to investigate the moderating role of Hofstede's national culture dimensions on ECI and RE. Individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence dimensions have a moderating role on ECI and enhance curbing CDE. High power distance and uncertainty avoidance have a moderating role on RE and reinforce the abatement of CDE.

The results of this study have significant implications for businesses looking to curb their CDE and increase corporate environmental initiatives. From a policy perspective, our findings can encourage policymakers and regulators to promote investment in environmental quality by spending on the development of energy-based technologies and ECI, and to provide infrastructure and markets for RE to make them accessible to users. Policymakers can also improve technology transfer between the public and private sectors by establishing public-private partnerships (PPPs). In addition, they are required to promote cultural dimensions such as individualism, long-term orientation, indulgence, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance due to their important moderating role in the relationship between REC, eco-innovation, and CDE. In addition, regulators are encouraged to monitor compliance with governance rules for public and private bodies and to improve national legislation or international convergence with governance principles. From a governance perspective, stakeholders are interested in mitigating climate change risks. Thus, they need to express their concern about environmental risk management, which could increase the pressure for legislative transformation to develop both governance best practices and environmental strategies [112]. In addition, they are required to engage more vigorously in the broad field of climate change by increasing investment in ECI and RE.

However, we acknowledge some limitations to our study that future research could address. In fact, it is crucial to recognize that the research findings should be interpreted cautiously, as the sample of the study is restricted to only the G7 countries. Therefore, we cannot generalize our results to other jurisdictions that may have diverse cultural dimensions and may deal with CDE differently. To broaden the study's focus, future research may compare our findings to those that might belong to other stock exchanges with a global presence, such as Dow Jones, DAX, CAC, Shanghai, Tokyo, and so on. Second, our study provides insights into association only and does not focus on causal relationships or the examination of different logics that may impact the association between RE and ECI on CDE. Future research may address these limitations. Finally, our study does not take into consideration the COVID-19 period effect. Therefore, we invite future researchers to conduct studies to better understand how the COVID-19 era affected the relationships “ECI-CDE” and “RE-CDE". Future studies can also incorporate additional variables such as trade openness and urbanization to account for potential omitted factors that could influence CO2 emissions which also helps in addressing the issue of endogeneity and omitted variables.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

khaoula Aliani: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hela Borgi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Noha Alessa: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Fadhila Hamza: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration. Khaldoon Albitar: Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R391), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Doğan B., Chu L.K., Ghosh S., Truong H.H.D., Balsalobre-Lorente D. How environmental taxes and carbon emissions are related in the G7 economies? Renew. Energy. 2022;187:645–656. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.01.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handayani K., Anugrah P., Goembira F., Overland I., Suryadi B., Swandaru A. Moving beyond the NDCs: ASEAN pathways to a net-zero emissions power sector in 2050. Appl. Energy. 2022;311 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murshed M., Rahman M., Alam M.S., Ahmad P., Dagar V. The nexus between environmental regulations, economic growth, and environmental sustainability: linking environmental patents to ecological footprint reduction in South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2021;28(36):49967–49988. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13381-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y.-J., Peng Y.-L., Ma C.-Q., Shen B. Can environmental innovation facilitate carbon emissions reduction? Evidence from China. Energy Pol. 2017;100:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olanrewaju V.O., Irfan M., Altuntaş M., Agyekum E.B., Kamel S., El-Naggar M.F. Towards sustainable environment in G7 nations: the role of renewable energy consumption, eco-innovation and trade openness. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.925822. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saidi K., Omri A. The impact of renewable energy on carbon emissions and economic growth in 15 major renewable energy-consuming countries. Environ. Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109567. Article ID: 109567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C., Pinar M., Stengos T. Renewable energy and CO2 emissions: new evidence with the panel threshold model. Renew. Energy. 2022;194:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.05.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su C.-W., Naqvi B., Shao X.-F., Li J.-P., Jiao Z. Trade and technological innovation: the catalysts for climate change and way forward for COP21. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;269 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Hongyi. A meta-analysis on the influence of national culture on innovation capability. Int. J. Enterpren. Innovat. Manag. 2009;10:353–360. 10:y:2009:i:3/4:p:353-360. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez-Herranz A., Balsalobre-Lorente D., Shahbaz M., Cantos J.M. Energy innovation and renewable energy consumption in the correction of air pollution levels. Energy Pol. 2017;105:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fethi S., Rahuma A. The role of eco-innovation on CO 2 emission reduction in an extended version of the environmental Kuznets curve: evidence from the top 20 refined oil exporting countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2019;26:30145–30153. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05951-z. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin B., Zhu J. The role of renewable energy technological innovation on climate change: empirical evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;659:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albitar K., Al-Shaer H., Liu Y.S. Corporate commitment to climate change: the effect of eco-innovation and climate governance. Res. Pol. 2023;52(2) doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2022.104697. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensah C.N., Long X., Boamah K.B., Bediako I.A., Dauda L., Salman M. The effect of innovation on CO 2 emissions of OCED countries from 1990 to 2014. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2018;25:29678–29698. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2968-0. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L., Chang H.L., Rizvi S.K.A., Sari A. Are eco-innovation and export diversification mutually exclusive to control carbon emissions in G7 countries? J. Environ. Manag. 2020;270 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hordofa T., Minh Vu H., Maneengam A., Mughal N., The Cong P., Liying S. Does eco-innovation and green investment limit the CO2 emissions in China? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 2023;36(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2022.2116067. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández Fernández Y., Fernández López M.A., Olmedillas Blanco B. Innovation for sustainability: the impact of R&D spending on CO2 emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;172:3459–3467. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chein F., Hsu C.C., Andlib Z., Shah M.I., Ajaz T., Genie M.G. The role of solar energy and eco‐innovation in reducing environmental degradation in China: evidence from QARDL approach. Integrated Environ. Assess. Manag. 2022;18(2):555–571. doi: 10.1002/ieam.4500. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jun W., Mughal N., Kaur P., Xing Z., Jain V., The Cong P. Achieving green environment targets in the world's top 10 emitter countries: the role of green innovations and renewable electricity production. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 2022;35(1):5310–5335. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2022.2026240. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji X., Umar M., Ali S., Ali W., Tang K., Khan Z. Does fiscal decentralization and eco‐innovation promote sustainable environment? A case study of selected fiscally decentralized countries. Sustain. Dev. 2021;29(1):79–88. doi: 10.1002/sd.2132. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qureshi M.A., Ahsan T., Gull A.A. Does country-level eco-innovation help reduce corporate CO2 emissions? Evidence from Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;379 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134732. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balsalobre-Lorente D., Shahbaz M., Roubaud D., Farhani S. How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to CO2 emissions? Energy Pol. 2018;113:356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arshed N., Hameed K., Saher A., et al. The cultural differences in the effects of carbon emissions — an EKC analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29:63605–63621. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-20154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X., Zhang S., Bae J. Nonlinear analysis of technological innovation and electricity generation on carbon dioxide emissions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;343 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131021. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman S., Kabir M.N., Talukdar K.H., Anwar M. National culture and firm-level carbon emissions: a global perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. 2023;14(1):154–183. doi: 10.1108/SAMPJ-05-2022-0228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhry S.M., Ahmed R., Shafiullah M., Huynh T.L.D. The impact of carbon emissions on country risk: evidence from the G7 economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin L., Kirikkaleli D., Hou Y., Miao X., Tufail M. Carbon neutrality target for G7 economies: examining the role of environmental policy, green innovation and composite risk index. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murshed M. An empirical analysis of the non-linear impacts of ICT-trade openness on renewable energy transition, energy efficiency, clean cooking fuel access and environmental sustainability in South Asia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2020;27(29):36254–36281. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09497-3. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad M., Jiang P., Murshed M., Shehzad K., Akram R., Cui L., Khan Z. Modelling the dynamic linkages between eco-innovation, urbanization, economic growth and ecological footprints for G7 countries: does financial globalization matter? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102881. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akram R., Ibrahim R.L., Wang Z., Adebayo T.S., Irfan M. Neutralizing the surging emissions amidst natural resource dependence, eco-innovation, and green energy in G7 countries: insights for global environmental sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2023;344 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118560. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharif A., Saqib N., Dong K., Khan S.A.R. Nexus between green technology innovation, green financing, and CO2 emissions in the G7 countries: the moderating role of social globalisation. Sustain. Dev. 2022;30(6):1934–1946. doi: 10.1002/sd.2360. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2011;2(1) doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chithambo L., Tingbani I., Agyapong G.A., Gyapong E., Damoah I.S. Corporate voluntary greenhouse gas reporting: stakeholder pressure and the mediating role of the chief executive officer. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020;29(4):1666–1683. doi: 10.1002/BSE.2460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiksel J. Design for environment: the new quality imperative. Corp. Environ. Strat. 1993;1:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keoleian G., Menerey D. Environmental Protection Agency; Cincinnati, OH: 1993. Life Cycle Design Guidance Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991;17(1):99–120. doi: 10.1177/0149206391017001. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barney J.B. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001;26(1):41–56. doi: 10.5465/amr.2001.4011938. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995;20(4):986–1014. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9512280033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z., Zhou Y., Zhang C. The impact of population factors and low-carbon innovation on carbon dioxide emissions: a Chinese city perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29:72853–72870 (May. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-20671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao Y., Chen P. Do renewable energy consumption and green innovation help to curb CO2 emissions? Evidence from E7 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023;30(8):21115–21131. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-23723-0. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Cairncross F. Harvard Business School Press; Boston: 1991. Costing the Earth. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willig J. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. Environmental TQM. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amit R., Schoemaker P.J. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strat. Manag. J. 1993;14(1):33–46. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250140105. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu J., Liu F., Shang Y. R&D investment, ESG performance and green innovation performance: evidence from China. Kybernetes. 2021;50(3):737–756. doi: 10.1108/K-12-2019-0793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeman R.E. Pitman; Boston, MA: 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman A.L., Miles S. Developing stakeholder theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002;39(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albitar K., Borgi H., Khan M., Zahra A. Business environmental innovation and CO2 emissions: the moderating role of environmental governance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1002/bse.3232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weng H.H., Chen J.S., Chen P.C. Effects of green innovation on environmental and corporate performance: a stakeholder perspective. Sustainability. 2015;7(5):4997–5026. doi: 10.3390/su7054997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rehman E., Rehman S., Mumtaz A., Jianglin Z., Shahiman M. The influencing factors of CO2 emissions and the adoption of eco-innovation across G-7 economies: a novel hybrid mathematical and statistical approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.988921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostadzad A. Innovation and carbon emissions: fixed-effects panel threshold model estimation for renewable energy. Renew. Energy. 2022;198:602–617. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.08.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khurshid A., Rauf A., Qayyum S., Calin A.C., Duan W. Green innovation and carbon emissions: the role of carbon pricing and environmental policies in attaining sustainable development targets of carbon mitigation—evidence from Central-Eastern Europe. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023;25(8):8777–8798. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02422-3. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wurlod J.D., Noailly J. The impact of green innovation on energy intensity: an empirical analysis for 14 industrial sectors in OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2018;71:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2017.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fethi S., Rahuma A. The impact of eco-innovation on CO2 emission reductions: evidence from selected petroleum companies. Struct. Change Econ. Dynam. 2020;53:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2020.01.008. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mensah C.N., Long X., Dauda L., Boamah K.B., Salman M. Innovation and CO2 emissions: the complimentary role of eco-patent and trademark in the OECD economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2019;26:22878–22891. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adebayo T.S., Oladipupo S.D., Adeshola I., Rjoub H. Wavelet analysis of impact of renewable energy consumption and technological innovation on CO2 emissions: evidence from Portugal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022;29(16):23887–23904. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17708-8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rahman M.M., Alam K. Effects of corruption, technological innovation, globalisation, and renewable energy on carbon emissions in Asian countries. Util. Pol. 2022;79 doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2022.101448. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z., Gao L., Wei Z., Majeed A., Alam I. How FDI and technology innovation mitigate CO2 emissions in high-tech industries: evidence from province- level data of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022;29(3):4641–4653. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dauda L., Long X., Mensah C.N., Salman M., Boamah K.B., Ampon-Wireko S., Dogbe C.S.K. Innovation, trade openness and CO2 emissions in selected countries in Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;281 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125143. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li W., Elheddad M., Doytch N. The impact of innovation on environmental quality: evidence for the non-linear relationship of patents and CO2 emissions in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;292 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112781. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y., Chen X. Spatial and nonlinear effects of new-type urbanization and technological innovation on industrial carbon dioxide emission in the Yangtze River Delta. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023;30(11):29243–29257. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24113-2. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu S., Hu X., Li L., Chen H. Does the development of renewable energy promote carbon reduction? Evidence from Chinese provinces. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;268 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110634. 110634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarkodie S.A., Strezov V. Effect of foreign direct investments, economic development and energy consumption on greenhouse gas emissions in developing countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;646:862–871. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu D., Song W. Does green finance and ICT matter for sustainable development: role of government expenditure and renewable energy investment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2023;30:36422–36438. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hao Y. The relationship between renewable energy consumption, carbon emissions, output, and export in industrial and agricultural sectors: evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022;29:63081–63098. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-20141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menyah K., Wolde-Rufael Y. CO2 emissions, nuclear energy, renewable energy and economic growth in the US. Energy Pol. 2010;38:2911–2915. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]