Abstract

The Nile Delta is Egypt's primary source of agricultural production. However, the Delta's capacity to remain Egypt's vital source of food security, rural development and economic stability is diminishing amidst persistent climate change risks. In this regard, this research gauges the impacts of climatic and anthropogenic factors on agricultural revenues and household wealth in Alexandria and Beheira, two of the Delta's most climate-vulnerable governorates. The research employs the Ricardian model by applying Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR), to test the impacts of climate change on real revenues from agriculture. Results show that quadratic temperature negatively impacts revenues from agriculture in Alexandria, while employment in agriculture, irrigation, livestock and machines positively contribute to revenues. In Beheira, results show that temperature and machines negatively contribute to agricultural revenues, while livestock contributes positively. The research further estimates the socioeconomic impacts of land degradation and desertification on individuals in Alexandria and Beheira by using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) robust standard errors. Individuals' socio-economic status, proxied by their wealth index (WI), is regressed on the Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI), gender, age, education, household size, work in agriculture and rural/urban residence. Outcomes reveal that individuals' wealth status in Alexandria is positively correlated with ESI, age, and education. In Beheira, land degradation, household size, rural areas and fathers working in agriculture are negatively correlated with wealth. Education, however, contributes positively to wealth. The study proposes policy implications that aim to foster the growth and development of rural residents in the Delta region.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Land degradation in Egypt's Delta region is caused by sea level rise and human activities which makes it difficult to undertake land reclamation and cultivation in some of its regions.

1. Introduction

The global food crisis is affecting millions of people around the world, despite persisting efforts to address this challenge. The number of people suffering from food shortages globally reached 828 million in 2021 [1]. In the Middle East and North Africa alone, the number of malnourished people reached 59.8 million, that is 12.9 percent of the population while the world average is 9.2 percent in 2022 [2]. Climate change is considered one of the main drivers of food insecurity. As populations increase, consumption needs and externalities induced by anthropogenic factors exert pressure on local systems that can lead to land degradation and desertification (LDD). The changing climatic conditions will have a severe influence on agricultural production, water, and food security [3]. It is therefore important to understand connections between land degradation and food access, particularly concerning how these dynamics affect well-being and poverty under climate change and variability.

Egypt is the most populous country in the MENA region. Hence, the productivity of its agricultural land that is within proximity to significant population and consumption nodes is important for food security, nutrition, and food access. Approximately 70 percent of Egypt's population are living on 3.50 US$ or less per day [4] and most low-income populations rely on the productivity of peri-urban land to supplement diets. Egypt is facing extreme environmental stressors as its urban population grows. Land degradation and desertification (LDD) are affecting Egypt's Nile Delta (and its main food source) making it one of the world's most vulnerable areas to climate change [5]. Although Egypt's population depends on agriculture for food and employment, the contribution of agriculture to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is low relative to its rising needs. The agricultural sector share of GDP is shrinking over time. Data from 1960 to 2021 show that Egypt's GDP share of agriculture has changed significantly over the past 60 years from a maximum of 28.81 percent in 1974 down to only 11.05 percent in 2019. Agricultural value added as a share of GDP and exports from agriculture have also declined over this period [6]. To fill in the demand for food gap, Egypt is relying on imports for more than 50 percent of its food consumption, the most important of which is wheat. The trend towards dependence on distant supply chains and marginalisation of Egypt's domestic agricultural production presents acute risks to its food security, its overall economic growth, food access and nutrition for low-income communities.

Desertification has increased in the Nile Delta and reflects a multifaceted socio-environmental process of land degradation (LD). This process is driven by a network of interactions including climate change, biophysical and socio-economic forces across macro and micro levels. Desertification in the Nile Delta is causing reductions in crop and livestock production. This is likely to lead to profound negative repercussions on Egypt's real GDP growth rate, agricultural output, health, socio-political stability, poverty, and inequality [5]. These consequences are likely to threaten the welfare (incomes, wealth, and consumption patterns) of millions of people residing in Egypt.

In-spite of the magnitude of the problem, recent literature is deficient on studies that examine the socio-economic impacts of land degradation and desertification (LDD) on Egypt's Delta region. In this regard, the objectives of this research are twofold: first, to analyse the extent to which climatic and anthropogenic factors impact agricultural revenues in Beheira and Alexandria. To accomplish that, real revenues from the five main crops produced in Beheira and Alexandria are regressed over climatic and anthropogenic factors using the Ricardian model, using Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR).1 Revenues from agriculture are a reflection of the land's capacity to produce crops, in addition to representing farmers' incomes. Second, the research gauges the socioeconomic impacts of land degradation and desertification on individuals in Alexandria and Beheira. The wealth index (WI) is used as a proxy for individuals' socioeconomic status, while the Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI) is the index for land degradation. The wealth index is regressed on the ESI and other socioeconomic characteristics (gender, age, rural residence, education, household size, work in agriculture) using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) robust standard errors. Results show that in Alexandria, quadratic temperature negatively impacts revenues from agriculture while employment in agriculture, irrigation systems, livestock and machines have positive impacts. Furthermore, wealth is positively correlated with land degradation, age, and education in Alexandria. In Beheira, livestock contributes positively to agricultural revenues, while temperature and machines contribute negatively. Additionally, wealth is negatively correlated with land degradation household size, fathers working in agriculture and rural residence. Education, however, contributes positively to wealth in Beheira.

The selection of the study area is driven by its importance on two fronts. First, Alexandria, Egypt's largest coastal governorate and its second largest city, is encountering high climate change risk from sea level rise (SLR). Second, Beheira is one of Egypt's largest Delta governorates which significantly contributes to national agricultural production and is subject to soil salinisation and desertification. Together, Alexandria and Beheira constitute 11 percent of Egypt's total population [4].

A wide array of studies focused on measuring the magnitude of environmental degradation in the Nile Delta region. Most studies were keen on measuring the impacts of soil quality and hydrological factors on agricultural output and revenues. Recently, studies have associated LDD with macro-economic indicators and sectoral level changes, while a select few qualitative studies have focused on the socioeconomic impacts of climate change on households' well-being. This study contributes to the literature by applying quantitative techniques that merge climatic and anthropogenic factors with micro-level data to estimate the socioeconomic impacts of LDD on individuals' wealth status in Alexandria and Beheira. Revenues from agriculture as well as household wealth are used as proxies for socio-economic status. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study that integrates micro-level indicators with climate change factors in Egypt's Delta region. The paper is organised as follows; section one provides the theoretical underpinnings relevant to the study and highlights a literature review. Section two describes the methodology and displays the regression results. Section three discusses the economic outcomes and analysis of the study, concludes and suggests policy implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical underpinnings

The relationship between desertification, land degradation and socio-economic development is complex and has become a subject of recent interest as climate change increasingly threatens communities’ socioeconomic wellbeing. Three environmental economics theories explain land degradation: the social cost theory, the theory of collective cost, and the theory of property rights [7]. The theory of social cost advocates that when economic agents fail to accept the full social costs of their actions (when externalities exist), factors of production are not optimally allocated, and markets are unable cope with externalities on their own [8]. The theory of social cost applies to land degradation when farmers mismanage their land and fail to bear the full costs of their actions. Related to the theory of social cost, is the theory of collective goods which states that land degradation occurs when users overexploit scarce environmental goods such as fertile areas of land by overgrazing, not conserving or maintaining the land. The theory of property rights shares with the previous two theories the relationship between externalities and land degradation but adds to them that disputed property rights make land users less inclined to conserve their land or invest in improving its productivity; that is, land users have no incentives to use the land in a socially optimal way [9]. An uni-causal view was developed from the previous theories which asserted that desertification is an artificial process caused by anthropogenic factors alone. However, this view was later refuted, and climate change was accepted as an additional driver of desertification [10].

Another dimension from scholars in the field of political ecology focused on the socioeconomic and political dimensions of land degradation. They emphasised the importance of soil-fertility management and soil depletion to social, economic, and political contexts to study the complexity of local farming systems, farmers' adaptability, and the rationale of soil investments. Additionally, discussions focused on structural factors and institutional forces behind resource degradation. Studies showed that farmers’ incentives and capacities to invest in land are influenced, not only by critical resources such as land, labour, and capital, but also by institutions and authorization structures that determine their access [11]. Other scholars raised concerns about the widespread neo-Malthusian hypothesis of the connection between population growth, poverty, and environmental degradation, which is frequently articulated in the soil-fertility debate. Emphasis was also on the nodes between poverty and environmental management that are influenced by other factors such as technologies, institutions, and policies [[12], [13], [14]]. It is universally accepted that land management must be understood within a full context including ecological, social, economic, and political factors, such that a combination of solutions is suggested to help increase agricultural production. Studies along these lines make cases for state interventions against land degradation [11].

The central theory in our study, Ricardian theory, extends from the natural science literature and addresses the physiology of crops. The Ricardian model, which is an application of the Ricardian theory, was developed to gauge the long-term impacts of climate change on agriculture while accounting for adaptation. The model is based on the foundation that changes in climatic factors lead to crop yield reduction. Both laboratory experiments and field experience reveal that crop production requires an optimum scale of climate by which it yields the highest growth and production levels. Similarly, non-optimal climatic conditions lead to lower growth rates and production levels. Factors such as soil, temperature and water may interact with climate to alter the climate-production relationship. The Ricardian model is a quadratic formulation of climate variables and a linear function of all other control variables. The linear and quadratic functions for temperature and precipitation capture non-linearities in the response of crops to the climate. Lab experiments with crops show that they tend to have hill-shaped functions with respect to temperature [15].

The initial application of the Ricardian approach was examined on farmland values across counties in the United States. The model analysed the extent to which the value of farmland differs across a set of exogenous variables (climate and soils) and assumes that farmers choose a number of available inputs and outputs to maximize their profits. By regressing land value on the exogenous variables, the Ricardian model measures the extent to which these variables impact land value in the long run [16]. The Ricardian method implicitly captures adaptation since farmers adjust inputs and outputs according to their local conditions, although the model does not show the explicit adaptation adjustments made by farmers. The model assumes that farmers maximize their profits and will choose the inputs that yield the highest revenues.

The Ricardian model was adapted for application to developing countries with a number of modifications. Developing countries may be short on accurate meteorological stations that capture temperature and precipitation data; hence, satellite data is used as an alternative. Another modification of the Ricardian method for application in developing countries is the lack of reliable measures of farmland value. To overcome this limitation, the Ricardian method was modified to use net revenues per hectare, as applied in our research. In addition to agricultural revenues, The Ricardian model considers two important components in agriculture in developing countries, irrigation and livestock. In this light, the theoretical foundation of the Ricardian model in our study is extended from the adaptation of the model to developing countries [15].

2.2. Empirical review highlights

The socioeconomic ramifications of climate change on agricultural net revenues in Egypt were earlier assessed in a qualitative study where the authors interviewed a sample of 900 households from 20 governorates across Egypt. The standard Ricardian model was used to regress farm net revenues on climate variables, soil quality, socio-economic and hydrological factors. Results revealed that an increase in temperature had substantial negative impacts on agricultural net revenues. However, the subsequent models in the study showed empirical evidence that farm net revenues improved to elevated temperature when heavy machinery, and hydrological factors (irrigation) were employed. Raising livestock as an adaptation strategy to combat climate change, however, was not effective in the study, owing to the prevalence of small-scale farming [17]. A study used General Circulation Model (GCM) to evaluate the economic impacts of climate change on various economic sectors in Egypt. Results showed that sea level rise and temperature impact agricultural production in the Nile Delta, accentuated by a reduction in water supply. The study further showed that unemployment and food prices are susceptible to increasing, risking malnutrition. Wider scale spill-over effects of climate change were also evident including increased particulate matter and heat stress facing Cairo inhabitants. This may lead to health hazards and a reduction in annual tourist revenues. Subsequent total economic losses were estimated to be between 200 and 350 billion Egyptian pounds, equivalent to 2−6 percent of Egypt's GDP [18].

The socioeconomic-LDD nexus has also been a topic of interest worldwide. The LDD-poverty nexus was studied globally by linking subnational socioeconomic data to measures of land ecosystems. The study used the instrumental variables approach to reach three main conclusions: First, land improvements are critical for poverty reduction in rural areas, particularly for Sub-Saharan Africa. Second, land improvements are pro-poor in that poorer areas benefit from larger poverty alleviation policies; and finally, irrigation plays a key role in breaking the climate change-poverty nexus [19]. An investigation on the interlinkages between land degradation and poverty in rural Malawi and Tanzania used simultaneous equation models. Findings suggest that poverty has negative impacts on land degradation owing to poor households' failure to invest in natural resource preservation and development. As a consequence, LD contributes to low agricultural productivity and aggravates poverty by 35 percent in Malawi and 48 percent in Tanzania. These findings emphasise the importance of incorporating land degradation into poverty analysis for rural households who primarily depend on agriculture for their livelihoods [20]. A qualitative study investigated the relationship between poverty dynamics and environmental degradation in Northern Ghana using semi-structured interviews to find that both poor and rich farmers contribute to desertification. The study indicates, however, that rich farmers contribute to the expansion of farming and to the pollution of water sources via agrochemicals. The study emphasised the urge to contextualise the poverty-environmental degradation nexus as part of power dynamics and political agendas of poor countries [21]. In continuation to the LDD-poverty nexus analysis, a qualitative study on Tunisia analysed the differential adaptation measures of farm households to environmental hazards based on livelihood levels. The outcomes showed that richer farmers prefer economic returns over environmental benefits. Farmers who pertain to the low-income group generated employment strategies that resulted in unsuitable land management, aggravating LDD. The explanation may be in the low accessibility of poor farmers to assets and credit needed for proper land management. Poor farmers are increasingly apprehensive about their immediate returns rather than medium and long-term sustainable land management techniques. Farmers in the middle-assets category take the most appropriate actions and are more flexible compared to the other two income levels. The study concluded that the quality of land is vastly dependent on its management and planning and on good understanding of the livelihoods, approaches, and perceptions of farmers as they remain the key drivers affecting land condition [22]. Alternatively, in Central Asia, poor farmers are more capable of coping with LDD drawbacks compared to rich farmers. Farmers’ profits were evaluated using a nationally representative agricultural household survey with remotely sensed data on land degradation. Results showed that land degradation reduced net agricultural profits of households across all income levels by 4.8 times. Poor agricultural households, however, were shown to be more able to cope with land degradation by applying sustainable land management practices. Reasons are that poorer farmers have higher incentives to adopt adaptation measures owing to their strong dependence on land for livelihood [23]. In the South Indian coastal delta, a study on the drivers of land degradation was estimated to show that coastal land degradation is caused by soil salinity. The study showed that social groups distinguished by caste, gender, and income levels experience LDD repercussions differently. A small percentage of the richer landowners benefited from changing rice paddy to shrimp aquaculture, which caused soil salinisation. The poor people had to bear the externalities of the declining productivity of the land for crop cultivation. This pushed the poor farmers to reduce or abandon cultivation and increase their reliance on non-agricultural sources of income, including outmigration. The study concluded that the absence of state efforts to restore land or alleviate widespread agrarian distress, LD led to a downward spiral with a few winners and many losers [24]. A study on 41 countries in Sub Saharan Africa 1996–2019 employed the generalised method of moments (GMM) approach to find a cyclical relationship between poverty and environmental degradation. This confirms, along with the previous literature, that an increase in poverty leads to an increase in environmental degradation, and vice versa. The study also confirmed that population growth, education, industrialisation, income inequality, institutional quality such as governance, control of corruption, freedom and civil liberty, democracy, fossil fuel energy use, household health expenditure, infant mortality rate, and agriculture productivity influence the nexus between poverty and environmental degradation [25]. In Somalia, a Cobb-Douglas production function for time-series data between 1962 and 2017 was used to show that land degradation is a definite contributor to declining agricultural output. The study revealed that increased land degradation increased rural poverty, which triggered rural migration and social conflict [26]. The relationship between living standards and land as a productive asset in developing countries was examined through the relationship between soil quality and living standards of households in 17 low-and middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The study indicated that LD was deteriorating and that a large share of rural populations lives on degrading agricultural land. Evidence suggested that land degradation has considerable implications on the living standards of millions of rural households in developing countries and for poverty alleviation overall [27]. The Ricardian approach was applied to test the effects of climate change on agriculture in North-Western Vietnam. The research used secondary data on 1055 households to examine the effect of minor changes in temperature and rainfall on Northwest farming. The study predicted the impact of climate scenarios on net revenue for the years 2050 and 2100 and found that the relationship between household revenue and climate variables are nonlinear, significant and inverted U-shaped. Predictions revealed that net revenues decreased as temperature and rainfall increased in the dry season [28].

It is widely acknowledged in the literature that climate change impacts LDD which in turn reduces agricultural output. The literature emphasises on integrating LDD into poverty analysis, political agendas and development plans, for designing pro-poor and informed policy implications.

The following section estimates the climatic and anthropogenic factors that impact agricultural revenues in Beheira and Alexandria on the governorate level using the SUR model.

3. Methodology

3.1. The impacts of climate change on revenues from agriculture in Beheira and Alexandria: A Ricardian approach using SUR

Cropland area is the total cultivated area of field crops and vegetables, cultivated over 3 crop cycles. Approximately, 8.5 million feddans are used for planting crops in Egypt, representing only 3 percent of the total land [29]. Cropland area is distributed as 5.9 million feddans in the ‘ancient’ irrigated land in the Nile Delta and 2.6 million feddans as newly reclaimed irrigated land [30]. The Nile Delta alone contributes to 47 percent of the total cultivated land in Egypt. Beheira, in turn, dominates agricultural production in the Delta region, contributing to 21.5 percent of the cultivated Delta land and 10 percent of the entire Egyptian cultivated land. Beheira contributes to 8.2 percent of Egypt's total agricultural production [4]. Alexandria, however, does not depend on agriculture as a main economic sector, however its limited agricultural land is prone to a potential full loss due to sea level rise. Cropland areas in Alexandria and Beheira are illustrated in Fig. 1 below. The cropland area is expected to decline, diminishing agricultural revenues, due to sensitivity to land degradation caused by sea level rise (SLR), alkalinity, anthropogenic factors such as inefficient land management, overirrigation, unsuitable cultivated crops to soil properties and deteriorated agriculture machines.

Fig. 1.

Total cropland area in Alexandria and Beheira (1990–2020).

Source: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics

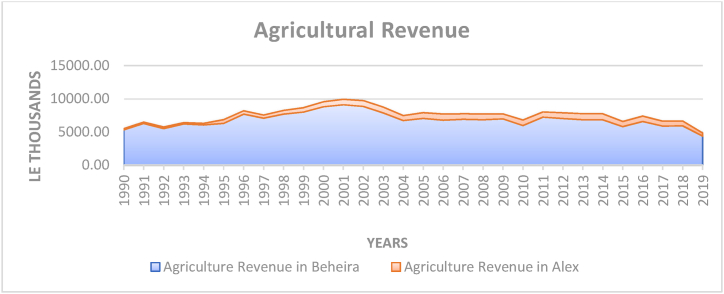

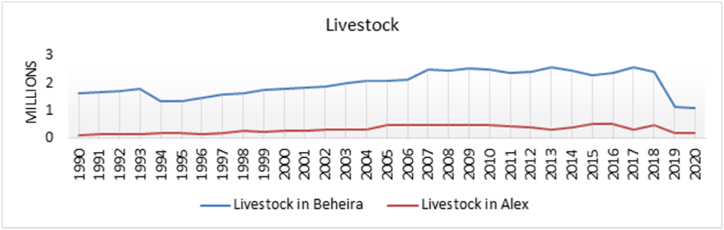

Revenues from agriculture from the five main crops grown in Beheira and Alexandria are shown in Fig. 2 below, where revenues in Beheira are much higher than in Alexandria. Livestock numbers shown in Fig. 3 below and are seen to increase over time until 2020 when the covid-19 pandemic and the foot-and-mouth disease spread amongst the livestock and led to their decline. Based on interviews with Dr. M. Abou-Kota and Dr. S. Ganzour,2 real revenues from agriculture are expected to decline owing to several reasons: Declining cropland areas in the Old Delta Region due to land degradation of varying degrees; increasing costs of inputs such as fertilisers, pesticides, seeds and sprouts; the contamination of certain inputs such as fertilisers, pesticides, seeds and soil conditioners that may lead to poor agricultural produce; farmers' reluctance to improve the strains and continue to depend on their own choice of seeds, this lowers productivity; farmers' over use of fertilisers without considering the actual need of the crop; the use of ineffective remedies for insects and fungal diseases; lack of a unified program for resistance and control of pests, and the inability to use agricultural mechanisation in harvesting operations causing massive waste of output; long distances between marketing centres and the land where crops are grown leads to loss of produce; the dichotomy between agricultural scientific research and the actual farms' needs and problems; modern technology solutions and different farming techniques suggested do not always conform with Egypt's diverse climate; lack of expenditure on agricultural innovation, training and monitoring of farmers; low agricultural skills and education; the lack of dissemination of information about successful agricultural models.

Fig. 2.

Agriculture Revenues in Alexandria and Beheira Aggregated from the 5 main crops (1990–2019).

Source: Authors' Calculations, Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics

Fig. 3.

Livestock in Alexandria and Beheira (1990–2020).

Source: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics [4].

To analyse the importance of the factors contributing to agricultural revenues in Beheira and Alexandria, this research uses the Ricardian model using SUR to estimate the relationship between real revenues from the five main crops and climatic and non-climatic factors. The following section describes the empirical analysis.

3.1.1. Data

The theoretical foundation of the model is based on the adapted Ricardian model for developing countries (explained in section 1.1 above) where real revenues from agriculture are regressed on quadratic climate variables, temperature and precipitation. Additional inputs that are used by farmers in the Delta region are also included such as irrigation, tractors and machines.3 Moreover, the Nile Delta is known for its high population density, hence, population data are included in the model.

Data on revenues from agriculture were obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture for the years 1990–2020. Revenues from Agriculture (AGRV) are aggregated from the five main crops in Beheira and Alexandria, namely, wheat, rice, cotton, maize, and beans. Revenues from the five main crops showed that wheat contributed with the largest share of revenues in both Beheira and Alexandria. This was followed by rice, maize, cotton, then beans in Beheira, and maize, rice, beans, then cotton in Alexandria. Revenues from the five main crops were adjusted for inflation as follows: Real Revenue = (Crop Production Value/PPI) *100. Climate variables include average precipitation (PRC) and average temperature (TEMP) for each governorate. The data on precipitation were based on ground station measurements and data on temperature was obtained from CAPMAS. Non-climate variables include Total Cropland Area (CA), Employment in Agriculture (EMP), Population Density (POPD), Irrigation (IRR), Irrigation Machines (IRRM), Livestock (LS) and Tractors (Tractors), obtained from CAPMAS [4].

The baseline relationship between revenues from agriculture and climatic and non-climatic variables, are specified in equation (1) below using the SUR method.

| dlogAGRVt = f (dlogCAt, dlogEMPt, dlogPOPDt, dlogIRRt, dlogIRRMt, dlogLSt, dlogPRCt, dlogTEMP, dlogTractorst) | (1) |

A quadratic formulation of climate variables and a linear function of control variables is used to apply the empirical examination of the Ricardian model using the SUR model for both governorates as specified in equation (2) below:

| dlogAGRVt = β0 + β1dlogCAt + β2dlogEMPt + β3dlogPOPDt + β4dlogIRRt + β5dlogIRRMt + β6dlogLSt + β7dlogPRCt + β8dlogPRC2t + β9dlogTEMPt + β10dlogTEMP2t + β11dlogTractorst+ εt | (2) |

where AGRV is real revenues from agriculture, CA is cropland area, EMP is employment in agriculture, POPD is population density, IRR is irrigation, IRRM is irrigation machines, LS is livestock, PRC is precipitation, PRC2, precipitation squared, TEMP is temperature, TEMP2, Temperature squared, Tractors is tractors, and ε is the error term.

The Augmented Dicky Fuller (ADF) test was applied to confirm data stationarity, but not all variables were stationary at levels; accordingly, the first difference was taken, after which all variables showed stationarity. ADF results are shown in appendix 2.

First, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) single equation model was used to regress real revenues from agriculture on the climatic and non-climatic variables shown above. However, OLS was deemed inappropriate owing to the affinity and interconnection between the variables since both governorates are geographically adjacent. Alexandria is a market for Beheira's agricultural products and relies on Beheira for agricultural labour. Such jointness allows for additional information beyond that is given by the OLS model, where individual equations are considered separately. Results of the OLS estimations for both governorates are shown in Appendix 2. Alternatively, Ricardian equations were estimated using the Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR), which allows for cross-equation parameter restrictions and correlated error terms. To test for the robustness of the SUR results, the correlation matrix of residuals, the covariance matrix of residuals and the Portmanteau test were run. Results confirming the relevance of the SUR approach are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Robustness test results - Residual correlation matrix.

| Test | Chi squared Stat | Tabulated Chi Square (0.05,4) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residual correlation matrix | 12.49 | 9.488 | Chi squared stat > tabulated chi squared. Therefore, SUR is more relevant than OLS |

Hypothesis test of the correlation matrix.

H0

There is no relationship between the error terms – relevance of the OLS model.

H1

There is a relationship between the error terms – relevance of the SUR.

With 5 per cent level of significance and four degrees of freedom, the calculated Chi square was compared to the Chi squared tabulated value, and therefore the Chi squared statistic is greater than the tabulated Chi square, indicating that the SUR model is more appropriate than OLS. X2 stat = 12.49 >X2 tab 9.488(0.05,4)

The Portmanteau test results showed that the Portmanteau probability values are more than 0.05 hence, no autocorrelation exists between the error terms.

3.1.2. Results of the impacts of climate change on revenues from agriculture in Beheira and Alexandria: A Ricardian approach using SUR

SUR regression results for Alexandria and Beheira are shown in Table 2 below. Results for Alexandria show that the strongest and only negative variable related with real agricultural revenues is temperature squared. This outcome is expected since Alexandria shows severe sensitivity to climate change owing to its location on a wide coastal front. The second strongest variable impacting real revenues from agriculture is tractors and machines, having a positive correlation. Since farmlands in this area primarily depend on large-scale production, tractors are mostly suitable. Third, livestock increases agricultural revenues on which farmers rely as an adaptation strategy, in the form of meat, milk and natural fertilisers. Livestock feed on clover that is readily available and planted in Beheira at a low cost, hence, this outcome is expected. Fourth, irrigation is positively correlated with revenues from agriculture as it naturally feeds the land with water and nutrients. Finally, the weakest positively correlated variable with revenues from agriculture is employment in agriculture, which is reflective of the relatively low number of labourers in the agricultural sector in Alexandria. This is evident that, adding labour hours to the existing few, is a possible confirmation of the law of diminishing marginal productivity. Results for Alexandria are all expected and are in alignment with the nature of the governorate.

Table 2.

SUR regression results.

| Region | Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | T-statistics | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLCA | 0.032 | 0.050 | 0.639 | 0.526 | |

| DLEMP | 0.177a | 0.048 | 3.696 | 0.000 | |

| DLPOPD | −1.459 | 1.272 | −1.147 | 0.259 | |

| DLIRR | 0.197b | 0.081 | 2.424 | 0.021 | |

| DLIRRM | 0.113 | 0.094 | 1.203 | 0.237 | |

| DLLS | 0.470a | 0.100 | 4.693 | 0.000 | |

| DLPRC | 0.016 | 0.029 | 0.547 | 0.588 | |

| DLPRC^2 | −0.008 | 0.013 | −0.622 | 0.538 | |

| DLTEMP | −1.267 | 0.713 | −1.778 | 0.083 | |

| DLTEMP^2 | −24.482b | 10.937 | −2.238 | 0.032 | |

| DLTractors | 0.491b | 0.222 | 2.215 | 0.033 | |

| Constant | 0.037 | 0.044 | 0.838 | 0.408 | |

| R-Squared | 0.63 | ||||

| Beheira | DLCA | 0.104 | 0.140 | 0.743 | 0.463 |

| DLEMP | −0.017 | 0.043 | −0.401 | 0.691 | |

| DLPOPD | 2.292 | 2.175 | 1.054 | 0.299 | |

| DLIRR | 0.007 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.935 | |

| DLIRRM | −0.037 | 0.027 | −1.366 | 0.181 | |

| DLLS | 0.328a | 0.116 | 2.831 | 0.008 | |

| DLPRC | 0.058 | 0.072 | 0.802 | 0.428 | |

| DLPRC^2 | 0.196 | 0.213 | 0.923 | 0.362 | |

| DLTEMP | −0.956b | 0.434 | −2.202 | 0.034 | |

| DLTEMP^2 | 3.163 | 3.116 | 1.015 | 0.317 | |

| DLTractors | −0.133b | 0.064 | −2.069 | 0.046 | |

| Constant | 1.189 | 0.599 | 1.981 | 0.055 | |

| R-Squared | 0.40 |

Note: Significant coefficients are in bold.

Significance at 1 % and.

Significance at 5 %.

Results for Beheira indicate that the significant and negatively contributing factors to real revenues from agriculture are temperature and tractors. Increases in temperature adversely impact agricultural revenues highlighting the negative repercussions of climate change on the agricultural sector in Beheira, albeit in a linear relationship. This relationship is expected since it is reflective of the lower effect that temperature has on agricultural revenues since Beheira is located on a narrower coastal front compared to Alexandria. Further, owing to small-scale farm holdings in Beheira, and to the degrading quality of machines, the use of machines/tractors is expectedly less efficient and contributes negatively. Livestock, on the other hand is positively correlated with agricultural revenues possibly as an adaptation policy.

Estimation results show that Egypt is witnessing an increase in the average annual temperature, a reduction in annual rainfall, sea level rise, salinisation and desertification of soils, in alignment with earlier studies and reports [31]. Furthermore, results on the impacts of temperature on agriculture revenues are in consensus with the literature [3,5,18,20,28,31,32]. Nevertheless, some studies found that machines and technological employment may reverse temperature's adverse effects on agricultural revenues [17]. This is an important result for investors in the sector. Results on livestock are mixed, however, since our study shows that raising livestock is positive and acts as an adaptation strategy, adverse to earlier studies on Egypt [17].

3.2. Impacts of desertification/land degradation on socio economic development of Alexandria and Beheira

A deeper understanding of the socioeconomic development of individuals in Egypt's Delta region requires a micro-economic lens. While macroeconomics focuses on the role of agriculture in national development allowing for macro policy interventions, microeconomics covers issues related to household behaviour. Farmers' decisions on land management practices have a critical role in either mitigating or exacerbating LDD. Rural households are closely related to their agricultural land, which is facing large climate change risks. These risks are having serious repercussions on agricultural revenues, household incomes and employment, which may push farmers to migrate to urban cities in search of better life opportunities.

In this light, this section aims to analyse the impacts of desertification on the socioeconomic development of individuals' household wealth on the district level in Beheira and Alexandria. This implies the need for incorporating knowledge on households (wealth, sex, age, education, employment, household size) with their immediate surroundings such as agriculture and climate conditions since Egypt's Delta region is home to many poor households. Experiencing sensitivity to climate change such as land degradation, is bound to have serious socioeconomic consequences on incomes of people living in the Delta, specifically those working in agriculture. These impacts are expected to exert pressure on food prices leading to food price inflation and threaten food security. Disaggregating climate change impacts on the micro-level data enables us to tailor policies that better target the poor.

The socioeconomic status of individuals living in Alexandria and Beheira are represented by microdata from the national survey, Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) the wave of 2018. The ELMPS 2018 is jointly conducted by the Economic Research Forum (ERF) and the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The survey presents extensive demographic and socio-economic data both on the individual and household levels, capturing features such as individual and household characteristics, household composition, assets attainment, wealth quintiles, parent and sibling life events, education, remittances, labour market composition as well as human resource development. The whole survey includes 61,231 individuals from 29 governorates. There are 3540 individuals in the survey from Beheira of which our sample is 1005 to represent individuals who are working in agriculture or have fathers working in agriculture; similarly, 2029 individuals in the survey are from Alexandria of which 398 are included in our sample who are working in agriculture or have fathers working in agriculture. The sample is adjusted by the use of sample weights (inflation factors) such that the sample better resembles the population it represents.

The wealth index is used as a proxy for the socioeconomic status of individuals in both governorates. Numeric measures of welfare (household income or consumption) are not readily available, incomplete, or unreliable. Individuals in our sample do not receive remittances from abroad, hence, their wealth is reflective of local sources of livelihood. The wealth index is based on both household durable and non-durable assets as a proxy of long-term wealth. Assets and infrastructure used in calculating the wealth index include land ownership versus rent, house ownership versus rent, type of dwelling, number of rooms per dwelling, number of persons per room, quality of housing material (type of floor material, type of wall material), type of sewerage, electricity, type drinking water, refrigerator, washing machine, iron, type of TV, radio, internet, bike, type of transportation, etc. By that, the wealth index is calculated by a selection of weighted indicators of household assets since the use of one single proxy is likely to lead to unreliable results. The wealth index used in the study is calculated and is made readily available by the ERF in the ELMPS.

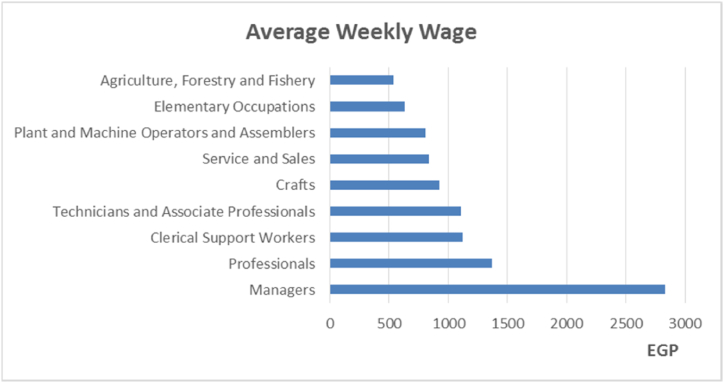

An analysis of the socioeconomic status of individuals living in Alexandria and Beheira who are working in agriculture or their fathers, show that they rank amongst the lowest earning occupations listed in the ELMPS 2018. Agricultural labour receives the lowest average weekly wage amongst all occupations as shown in Fig. 4 below and are reported to have amongst the lowest wealth index levels as seen in Table 3 below. Their vulnerability is further exacerbated by the diminishing agriculture sector, and its limited capacity to absorb more labour owing to its sensitivity to climate change. The agriculture sector does not provide sufficient employment opportunities, mainly owing to constraints on production expansion. More rewarding employment prospects, in which working members of households may find jobs, are in the development of non-farm sectors.

Fig. 4.

The average weekly wages per listed occupations.

Source: Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF).

Table 3.

Wealth index by occupation.

| Current Occupation | Alexandria's Wealth Index | Beheira's Wealth Index |

|---|---|---|

| Professionals | 0.31 | 1.4 |

| Technicians and Associate Professionals | 0.08 | 0.51 |

| Managers | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Services and Sales | −0.28 | 0.19 |

| Clerical Support Workers | −0.03 | 0.7 |

| Craft Workers | −0.36 | −0.1 |

| Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers | −0.41 | 0.16 |

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery | −0.48 | −0.16 |

| Elementary Occupations | −0.72 | −0.26 |

Source: Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF).

Table 4 below shows that approximately half of the labour force in Beheria is working in agriculture and fishery compared to a negligible number in Alexandria. Since the sample is representative of the total population, we may conclude that half of the labour force in Beheira is working in agriculture and are living in poverty as is reflected in their weekly wage rate and wealth index.

Table 4.

Occupations’ share of total population.

| Current Occupation | % Share of the Total Sample in Beheira | % Share of the Total Sample in Alexandria |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery | 47.9 | 4.1 |

| Service and Sales Workers | 15.9 | 23.8 |

| Craft and Related Trades Workers | 10.4 | 16 |

| Professionals | 9 | 15.2 |

| Plant and Machines Operators, and Assembly | 4.6 | 15.4 |

| Technicians and Associate Professionals | 3.8 | 5.8 |

| Managers | 2.9 | 4.3 |

| Clerical Support Workers | 2.9 | 11.4 |

| Elementary Occupation | 2.6 | 4 |

Source: Authors' Calculations, Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF)

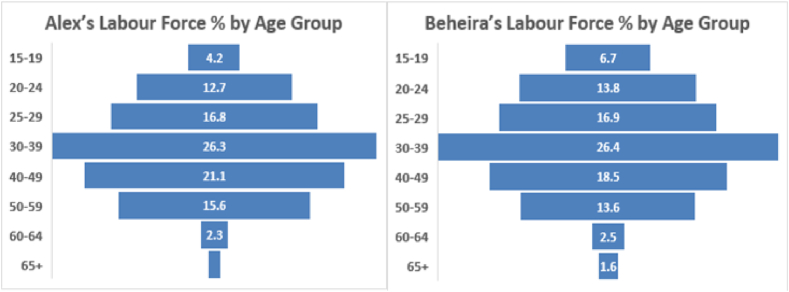

The demographic composition of the labour force living in Alexandria and Beheira as shown in Fig. 5 below, shows that the labour force in each governorate is mostly concentrated in four main age groups: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59. However, 70 percent of the agricultural labour force is between the age groups of 20–50. This represents a youth bulge where a young population is yet expected to expand. Given the limitations on agricultural wages and the vulnerability and poverty of people living in the delta region, risks of urban encroachment on fertile land are high.

Fig. 5.

Labour force by age group.

Source: Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF)

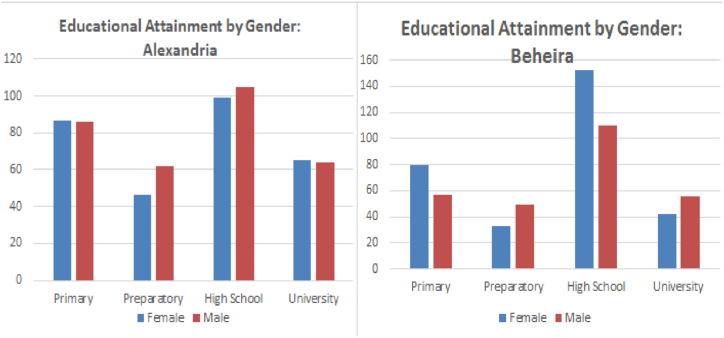

The segmentation of agricultural labour by gender, as seen in Fig. 6 below, shows no gender discrepancy in agricultural employment since both females and males contribute alike to the agricultural labour force. It is seen that 50.67 per cent of those working in the agricultural sector are males and 49.3 percent are females; similarly, in Beheira, 50.65 percent are males and 49.35 percent are females. Fig. 7 below shows educational attainment by gender, indicating that both males and females have equal access to schooling. The figure highlights that females surpass males’ years of schooling in Behera in high-school level.

Fig. 6.

Agriculture labour by gender.

Source: Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey, (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF)

Fig. 7.

Educational attainment by gender.

Source: Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018), Economic Research Forum (ERF)

The bulk of the labour force in Beheira and Alexandria are between the ages 25 and 59, with a household size of 5 individuals on average, alarming poverty rates, increasing population growth and high population density. Widespread urban sprawl is seen to increase (illegally) since revenues from keeping agricultural land diminished over time compared to investing in housing. The outcome was that individuals trade the less rewarding land for buildings to ensure short term gains. The survey also shows that upward social mobility exists between parents and their children, as children attain higher educational levels compared to both their parents’, [33]. The following section provides an estimation of the impact of land degradation/desertification on socioeconomic development of individuals in Alexandria and Beheira on the district level.

3.2.1. Data

The Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (ELMPS, 2018)4 presents valuable cross sectional socioeconomic data that is used to gauge the relationship between households’ wealth and climate indicators. The socioeconomic variables used are wealth index, agricultural activity as current occupation, agricultural activity as a current occupation of the father, average years of schooling, household size, age, sex, living in urban versus rural areas. Individuals pertaining to each household have their own wealth index which is readily available in the survey to represent their socioeconomic status. Households are then clustered over districts, and for each district a climate variable is calculated and designated. The Climate variable which is the level of sensitivity to land degradation/desertification is represented by the Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI).5

3.2.2. Methodology

The wealth index, the dependent variable, is regressed on the Environmental Sensitivity Index (ESI), and on socio-economic variables by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) using robust standard errors. This is done by using cluster robust standard errors which are designed to allow for correlation between observations within a cluster. Socio-economic variables are represented by dummy variables as follows: whether the individual is working in agricultural activities as a current occupation (Yes = 1 No = 0), whether the individual's father is working in agricultural activities (Yes = 1 No = 0), gender (1 = female 0 = male), living in urban/rural area (1 = rural 0 = urban); additionally variables included are average years of schooling, household size and age.

The General Equation:

| WI(i) = f (LD (i) YS (i), AGREMP (i), Father's AGREMP, HSize (i), Gender (i), Age (i), Rural(i) +ε(i) | (3) |

where LD is land degradation, YS is years of schooling, AGREMP is agriculture employment as the individual's current occupation, Father's AGREMP is father's agriculture employment as a current main occupation, HSize is household size, Gender is gender, Age is age, Rural is rural/urban.

Alexandria's OLS Equation:

| WI(i) = β0 +β1 LD(i) + β2 YS(i)+ β3 AGREMP(i) +β4 Father's AGREMP(i) + β5 HSize(i) +β6 Gender (i)+ β7 Age(i) +ε(i) |

Beheira's OLS Equation:

| WI(i) = β0 +β1 LD(i) + β2 YS(i)+ β3 AGREMP(i) +β4 Father's AGREMP(i) + β5 HSize(i) +β6 Gender (i)+ β7 Age(i) +β8 Rural(i) +ε(i) |

3.2.3. Results of the impacts of desertification/land degradation on socio economic development of Alexandria and Beheira

Results for Alexandria are shown in Table 5 above, and they reveal a significant positive relationship between land degradation and the wealth index. Expectedly, individuals in Alexandria are replacing their agricultural land with more financially rewarding uses. Other economic activities are increasingly becoming more attractive owing to the land's diminishing capacity to produce crops. Land degradation due to sea level rise and salinisation drove individuals to make efficient use of buildings and factories. Further, age has a positive relationship with wealth which relates to the life-cycle hypothesis, whereby individuals have positive wealth prospects over time. Years of schooling also positively contribute to wealth in Alexandria, corresponding to the rising enrolment in higher education. The results further show that household size, working in agriculture, fathers' employment in agriculture, as well as gender are insignificant. Results for Alexandria are in consensus with the literature that temperature has a quadratic effect on agriculture and that farmers who belong to the relatively higher income levels have a positive relationship with LDD [22,24,34].

Table 5.

Alexandria OLS regression results.

| Wealth Index | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-statistic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Degradation | 9.43a | 2.335 | 4.04 | 0.000 |

| Household Size | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.60 | 0.550 |

| Age | 0.012a | 0.003 | 3.67 | 0.000 |

| Gender | −0.065 | 0.1 | −0.65 | 0.516 |

| Years of Schooling | 0.111a | 0.009 | 12.88 | 0.000 |

| Agriculture Employment | −0.073 | 0.196 | −0.37 | 0.709 |

| Father Agriculture Employment | −0.061 | 0.165 | −0.37 | 0.711 |

Note: Number of observations:398; Dependent. Var: Wealth Index (WI); R -Squared: 0.37; Adjusted R-Squared: 0.36; Prob˃ F = 0.0000 Bold indicate significance.

significant at 5 %.

Results for Beheira are shown in Table 6 above and reveal that land degradation has a significant negative relationship with wealth. As a consequence, investments to rehabilitate the land and prevent it from deteriorating into desertification are pressing. Individuals who are dependent on agriculture as an economic activity in Beheira will get poorer as land degradation worsens. Results show that living in rural Beheira has a significant negative contribution to wealth since wages received in rural areas are low and the most financially rewarding economic activities pertain to urban jobs. Household size has a significant negative contribution to wealth in Beheira, while schooling positively contributes to individuals’ wealth indicating the importance of education. Finally, fathers working in agriculture and employment in the agricultural sector are both insignificant factors. The inverse relationship between LDD and living standards in Beheira is in line with [20,23,[25], [26], [27]].

Table 6.

Beheira OLS regression results.

| Wealth Index | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-statistic | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Degradation | −5.223a | 1.428 | −3.66 | 0.000 |

| Household Size | −0.026a | 0.012 | −2.24 | 0.026 |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.002 | 1.50 | 0.133 |

| Gender | 0.041 | 0.043 | 0.97 | 0.334 |

| Years of Schooling | 0.048a | 0.004 | 12.91 | 0.000 |

| Agriculture Labour | 0.009 | 0.048 | 0.18 | 0.859 |

| Father Agriculture Labour | −0.129a | 0.042 | −3.08 | 0.002 |

| Rural | −0.133a | 0.050 | −2.61 | 0.009 |

Note: Total Number of Observations: 1005; Dependent. Var: Wealth Index (WI); R-Squared: 0.23; Adjusted R-Squared: 0.23; Prob˃ F = 0.0000; Bold indicate significance.

significant at 5 %.

When climate change risks exacerbate poverty and unemployment individuals or families may migrate to nearby areas seeking better life opportunities. The following section provides an analysis of climate mobility dynamics for the Nile Delta Region and projections for future mobility prospects.

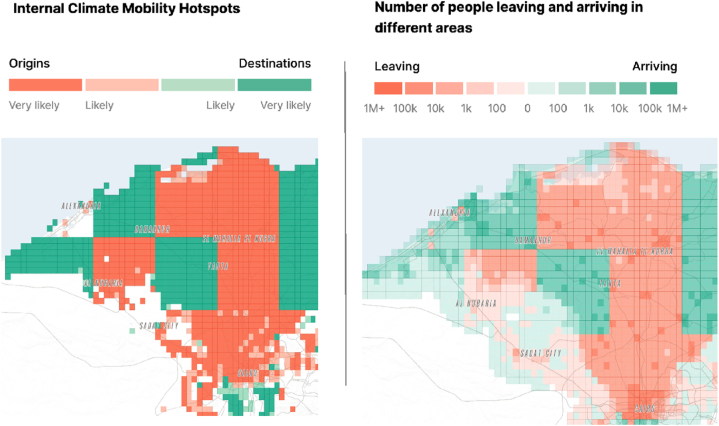

3.3. Climate mobility: climate induced displacement and migration

The African Shifts report highlights that many coastal cities in north, west, southern, and east Africa are likely to be hotspots of climate mobility: that is movement of human populations in response to the impacts of climate change. In the Nile delta, climate mobility dynamics are mixed [35] The continental trend for Africa shows there will be an initial increase in climate mobility into coastal zones up till 2030, but the trend will turn after 2030 as sea level rise and increasing riparian flooding begin to affect coastal areas, and by 2050 people are projected to leave these areas under both high emission scenarios [35].

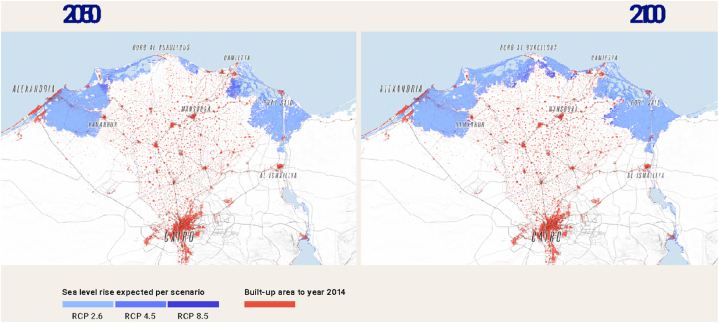

While the Cairo area appears as a source area of climate mobility, some nearby zones in the Nile Delta and the Mediterranean coast, including Alexandria, appear as destination areas based on their attractiveness, relative to many other cities. For some coastal cities, beyond sea level rise, flood risk from rivers will also result in significant displacement [35]. A significant part of the population in the Nile delta will be exposed to sea level rise risk, including part of the 5.3 million people projected to live in Alexandria and surroundings by 2050. However, the majority of people might prefer to stay due to their ties to the land or the means they might lack to move and start over in a different location [35]. Fig. 8 above shows projections of sea level rise for Cairo and Alexandria (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Projections of sea level rise for Cairo and Alexandria [35] 6.

Fig. 9.

Projected climate mobility for the Nile Delta Region showing climate mobility hotspots (left) and total numbers of population movements out, to and across the Nile Delta Region (right) in response to the impacts of climate change [35].7.

The projected magnitude and direction of internal climate mobility will vary across space and time, and across future scenarios. However, for some areas (grid cells) the results of multiple scenarios agree on the direction of population change (increase vs. decrease or arrivals vs. departures). Those areas where the results of the Africa Climate Mobility Model are consistent across three or more future scenarios are represented here as so called “hotspots” of internal (within country) climate mobility. Hotspots are geographic areas that, regardless of the emissions and social development scenario, will likely become climate mobility origins or destinations in the future.

Several cities will see climate impacts drive people out of urban areas or away from more exposed to less risky areas within the city. Of the top four climate mobility source cities — Accra, Desouk, Casablanca and Asmara — the first three are coastal or on major rivers and are projected to experience increases of either sea-facing or river system flooding.

The climate mobility projections for coastal areas like those of Egypt's Delta suggest that, despite growing risks, people will move to and remain in cities along the coasts, tolerating flooding, erosion and other climate risks as the price to pay for access to opportunities. Many migrants take a calculated risk when they compare the potential gains and losses of migration with those of staying, given the conditions in their home communities [35]. Many of those who are willing and capable of absorbing the considerable financial and physical risks of moving in the near-term do so to achieve a multi-generational leap in social mobility. This has important implications for policy. People may claim a right to remain in vulnerable and hazard-prone areas and reject efforts at moving them, such as through planned relocation. This is particularly true if they are not able to meet their economic and livelihood needs otherwise, and if they are not able to address the non-material loss and damage associated with displacement [35].

This was the case for respondents to the ACMI survey in Al Max where mobility is not a feature of the population. Almost all (92 %) respondents reported that no one from their household had moved away from the area [35]. Only 5 % said it was normal and expected for people to move from the area, while 75 % reported that moving away was unusual and unexpected. Residents of Al Max were generally not in favour of moving from the area. Despite repeated government warnings that parts of Al Max are unsafe and not fit for habitation, people are reluctant to move, especially fishing families who need and want to be close to their boats and the water due to their source of livelihoods, irrespective of their living conditions and risks. Of those who left Al Max, the majority went to another part of Alexandria or to Cairo. It was mainly young men who moved, while older people were the least likely to move [35].

The second major finding of the Al Max case study was the widespread acquiescent immobility; people do not have the resources or capability to migrate, and neither do they have the aspiration to do so. It appears that immobility was the clear preference: people wished to remain in their community, in their profession, and in the environment, they know and value surrounded by their families and close networks. This was despite generally low income and education levels. The “unchanging” nature of Al Max was also strongly expressed through this study. Participants felt their world had not changed significantly in the recent past, and they did not predict that it would in the coming years. Furthermore, they felt their own lived experience of Al Max was shared by most other community members. The desire to stay was not reflected by extremely high satisfaction with life in Al Max, but possibly simply reflects a strong sense of belonging. The evidence suggests that when environmental factors such as flooding and pollution start to affect the population more, residents are likely to resist mobility up to an extreme point – up to where the means of survival are almost completely taken from them. This would be an extreme scenario, probably many years off, but in the meantime, climate-related events and processes are likely to have increasingly negative impacts on the population [35]. Climate induced displacement complicates the socioeconomic impacts of land degradation. In this regard, it is essential to analyse this issue further and to suggest relevant policy implications.

4. Conclusion, economic analysis and policy implications

The socioeconomic-LDD nexus reveals a significant correlation in both Alexandria and Beheira and has serious economic implications on the macro and micro levels. Consequently, climate change's impacts on agriculture causes a significant threat to Egyptian national and household food security [3,5,31]. Resulting in considerable reductions in real revenues from agriculture because of temperature increases, Alexandria faces the greater risk. Beheira is the Delta's largest crop producing governorate and has a considerable number of poor rural inhabitants working in agriculture and are becoming increasingly vulnerable. Stifled with outdated machinery, Beheira's farmers turn to livestock as an adaptation policy to make up for income losses. But because farmers depend on agricultural income for basic survival, land degradation withers away farmers' wealth. The most vulnerable are people living in rural Beheira, large families and individuals who have fathers working in agriculture. Education, however, gives people in Beheira a glimpse of hope about their future wealth perspectives, conditional on employment availability. For Alexandra, the narrative is different; farmers substitute land for alternative polluting uses that have wealth increasing effects. Improving household incomes in Egypt is a challenge since climate change will increasingly become the main driver of agricultural volatility and infrastructure deterioration for decades to come. Along with its rising population, income distribution, urban sprawl and technological capabilities, Egypt has limited options owing to inadequate scientific understanding of the climate change-socio-economic nexus that is shrouded by complexity. Policy implications need to be inclusive of social, economic, and environmental dimensions and incorporate all segments of the population for just transition to occur gradually.

4.1. Alexandria

In Alexandria, the positive wealth-LDD relationship acts as a disincentive for investors in agriculture, especially amongst the private sector. Substituting agricultural land with real estate development, cement factories, petroleum refineries, black carbon firms, induces lack of trust in agricultural investments creating a domino effect. The chain reaction of accumulating environmentally hazardous projects, results in severe environmental degradation. Actions of encroaching on agricultural land inflates land prices creating a bubble effect [30]. Clearly, land use decisions seldom consider public costs and focus only on private benefits. Where agents do not bear the consequences of their actions, externalities arise creating market inefficiency, as advocated by the social cost theory.

Patterns of similar interactions between the socio-environmental systems may be the product of institutional failures, distorted market prices, incorrect incentives, defective or unenforced property rights and absence of information about the damages pertaining to LDD. Such factors prevent farmers from investing in sustainable land management (SLM) and soil conservation measures [32]. Hence, a comprehensive economic framework of good governance that guides incentives, investments and institutional action needs to be enforced in order to make informed decisions about prioritising action.

On the labour market front, similar successful attempts of sectoral shifts reflect on demand for skilled labour. Demand for a different set of skills arises, forcing agricultural labour into unemployment, hence, initiating an influx of (usually) internal migration. Farmers who move to urban cities are usually ill-equipped for jobs that are readily available there. They usually resort to the informal market working as street vendors or inhibit low-skilled jobs with little and irregular income. Whole families might move to slum areas adding pressure on already dense urban areas. Farmers’ children who have achieved upward social mobility and have dropped out of the agricultural labour force, migrate to urban cities looking for better life opportunities. UN-Habitat Egypt (2023) states that current villages and cities are largely surrounded by valuable agricultural land but are threatened by rapid and unplanned urban encroachment. Approximately, 40 percent of urban areas and 95 percent of rural areas in Egypt are unplanned. Accessibility to affordable housing is a challenge that threatens most low-income Egyptians. Living in rural or informal areas with poor facilities, many people lack access to water, public services, and transportation.

Implications for the above-mentioned outcomes in Alexandria may start by discouraging farmers from embarking on alternative uses to agricultural land. Backward and forward linkages to agriculture may be encouraged via incentives [36]. The evidence supporting the importance of linkages for agricultural development ranges from macro econometric and structural modelling of intersectoral growth linkages, to microeconomic and value-chain analyses of growth opportunities [37]. Linkages to nonfarm sectors form lucrative employment opportunities for the labour force who are dropping out of agriculture. People-positive adaptation efforts could build resilience and agency in the face of climate impacts. With the right incentives, some people to stay where they are rooted, help those who aspire to move to do so in a safe and informed manner, support communities that receive migrants, and anticipate and plan for situations where whole communities may need to relocate [38]. Recognising and supporting mobility as a legitimate coping and adaptation strategy can reduce the risks for those who move and allow communities to remain rooted in place. In the context of slow-onset climate impacts, it is rarely whole households or communities who relocate. Instead, some members leave to pursue opportunities and often support those staying behind. The resulting networks can strengthen resilience at a household and community level by diversifying revenue and support structures [38].

4.2. Beheira

LDD has detrimental implications on poor rural families in Beheira. Farmers earn low wages and are responsible to feed large families. Being constrained by little to no credit facilities, farmers are incapable of investing in sustainable land management practices. Consequently, a cyclical effect emerges between LDD and poverty. Typically, poor rural farmers have a high time preference, such that they attach more value to the present and discount the future at a higher rate. In addition to being categorised as risk averse, poor farmers randomly add low-cost additives to the soil for premature harvesting; the results being low-quality crops. Extended from the social cost theory and the theory of collective goods, this kind of land mismanagement and lack of conservation by famers is the result of low incentives to invest in improving productivity. Poor land use, chemical inputs, monoculture farming, over grazing and poor irrigation practices, diminish production triggering food price inflation through a multiplier effect. Inflated wheat, corn, beans, maize and rice prices (Egypt's five main strategic crops), will lead to a food security crisis, prompting malnutrition, conflict and forced migration. Serious long-term repercussions of a diminishing agricultural sector in Egypt fosters a reduction in its share of GDP. The relative share of agriculture to GDP and employment has declined recently as part of the structural transformation of the Egyptian economy, although output expanded [31]. Nevertheless, the low elasticity of demand for strategic crops, is expected to increase reliance on imports, hurting Egypt's already large balance of payments deficit.

Policies that induce investing in agriculture and education combined, enhances land management strategies and reverses adverse effects of the LDD-poverty nexus [18,19]. One of the primary arguments for investing in agriculture is that poverty elasticity of economic growth is much higher in the agricultural sector relative to other sectors of the economy. That is, agricultural sector growth leads to poverty reduction more than growth of the same magnitude in other sectors of the economy [39]. Through the ‘agriculture-first hypothesis,’ the agricultural sector is seen to play a vital role in poverty reduction. Hence, questions related to economic growth and poverty reduction need to consider the stability of the agricultural sector as a core priority in socioeconomic development. Through a Lewis-type structural transformation, investing in agriculture where the poor work, has proven more effective for poverty reduction than taking the poor out of agriculture and to an urban-industrial environment. Hence, the low-income communities are not found in agriculture due to adverse selection. Poverty reduction has proven to be more effective through productivity growth, links to forward and backward linkages, and extending credit, than through structural transformation [40].

Deteriorating climate conditions are worsening the positions of small farmers, especially that agricultural development critically depends on financial availability. Farmers are constrained in credit markets by facing asymmetric information, adverse selection, and moral hazard. Unlike other sectors, financial institutions are more reluctant to provide financial services to small farmers owing to the associated high default costs. Moreover, the lack of collateral owned by small farmers adds to the difficulty of accessing credit. Although policy makers in Egypt are already enhancing financial inclusion (individuals' and business’ ability to access financial services) the policy should actively incorporate rural small communities to make it easier to monitor credit extended to them. The government should enable increased financial access to small farmers as risk mitigating factors, for short-term and long-term investments in modern technology for the development SLM.

The introduction of high-value subsidised agricultural products (vegetables, fruits, and livestock products) may help farmers deal with market failures. Farmers face price risks in what is known to be a volatile market. The ability for farmers to attain improved imported seeds, safe pesticides will enable quality resilient farming. Moreover, offering a fixed product price in advance is one way for farmers to undertake new businesses through contract farming. Local supermarkets and agro processors are good opportunities to overcome these market failures. Supermarkets and agri-processors offer inputs on credit and production instruction to farmers. Studies found that farmers who are engaged in contract farming are the larger or wealthier farmers/landowners [41,42].

The agricultural growth linkage hypothesis suggests that agricultural technology drives development in the non-farm sector via numerous production linkages [43,44]. Investing in enhanced agricultural technology may spur development of industries that cater for agricultural inputs as well as service-related support to the agriculture sector (repair shops for machinery and delivery of inputs). Additionally, investments in food processing and agro-based manufacturing industries serve as linkages to agricultural supply. Creating such pro-poor non-farm jobs are promising because landless and near-landless households that belong to the poorest and vulnerable segments of the rural society actively seek nonfarm jobs than landed households. The development of non-farm sectors has the potential to affect the income distribution of families through wages. In the long run, the non-farm sector may succeed in absorbing the surplus rural labour force causing real wages to increase, what is known as the Lewis turning point which has its implications on poverty reduction as well as agricultural production as was evident in China [45].

The current research renders benefits when replicated in studies on climate-risk regions, where populations are poor and depend on agriculture for livelihood. We suggest the replication of this study to additional areas in Egypt that are threatened by LDD. These regions include the North Coast, which is at the forefront of climate risk, facing severe LDD as a result of salinisation and high ground water levels. Areas in the North Coats include Al-Hammam, Marsa Matrouh, Apis region, and the Tina Plain. Additionally, Nile Delta governorates such as Kafr El Sheikh, Rashid, Damanhur, Beni Suef, Sohag and Minya are also at risk of LDD and may benefit from the replication of this study [46].

Data availability

Data was made available by the Ministry of Agriculture, CAPMAS and ERF. The ESI index was calculated as referenced in the following paper: Aboukouta, M. E. S., Hassaballa, H., Elhini M., and M. Ganzour, S. K (2024). Land degradation, desertification & environmental sensitivity to climate change in Alexandria and Beheira, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Soil Science, 64(1), 167–180.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maha Elhini: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hoda Hassaballa: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Nicholas P. Simpson: Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Maha Balbaa: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Remah Ibrahim: Data curation. Sameh Mansour: Resources, Data curation. Mohamed E. Abou-Kota: Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Shaimaa Ganzour: Software, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Orange shows built-up area in 2014. Shades of blue show permanent flooding due to sea level rise by 2050 and 2100 under low (RCP2.6), intermediate (RCP4.5) and high (RCP8.5) greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. RCP8.5 and RCP 4.5 are included in this Figure together with RCP2.6 to show the potential range of sea level rise and risk by 2050 and 20,100 even for ranges lower than RCP6.0. Darker colours for higher emissions scenarios show areas projected to be flooded in addition to those for lower emissions scenarios. The figure assumes failure of coastal defences in 2050. Some areas are already below current sea level and coastal defences need to be upgraded as sea levels rise. Blue shading shows permanent inundation surfaces predicted by Coastal Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) given the 95th percentile K14/RCP2.6, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, for present day and 2050 sea level projection for permanent inundation (inundation without a storm surge event), and RL10 (10-year return level storm). Low-lying areas isolated from the ocean are removed from the inundation surface using connected components analysis. Current water bodies are derived from the SRTM Water Body Dataset. Orange areas represent the extent of coastal human settlements in 2014 (Pörtner et al., 2022; Amakrane et al., 2023).

Explore the ACMI data here: https://africa.climatemobility.org/explore-the-data/internal-climate-mobility.

Zellner's seemingly unrelated regression, Stata Manual (2022).

Dr. Shaimaa Ganzour & Dr. M. Abou-Kota are researchers in The Soil, Water & Environment Research Institute, Agriculture Research Centre (ARC), Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture.

Dr. M. Abou-Kota researcher in The Soil, Water & Environment Research Institute, Agriculture Research Centre (ARC), Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture.

Economic Research Forum (ERF), Egypt Labour Market Panel Survey (2018).

Abou-Kota, M. E. S., Hassaballa, H., Elhini M., and M. Ganzour, S. K (2024). Land degradation, desertification & environmental sensitivity to climate change in Alexandria and Beheira, Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Soil Science, 64(1), 167–180.

Appendix.

Table A2-1.

Results of the augmented Dicky– Fuller unit root test in Alexandria

| Variable | Level |

First difference |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Prob | Statistic | Prob | |

| LAgricultural Revenue | 0.210 | 0.969 | −4.956 | 0.000 |

| lCropland Area | −2.629 | 0.099 | −4.896 | 0.000 |

| LEmployment in Agriculture | −2.939 | 0.053 | −8.211 | 0.000 |

| LIrrigation Machines | −1.849 | 0.351 | −5.499 | 0.000 |

| LLivestock | −1.064 | 0.717 | −4.614 | 0.001 |

| LPopulation Density | 1.104 | 0.997 | −5.469 | 0.000 |

| lPrecipitation | −4.271 | 0.002 | −5.376 | 0.000 |

| LTemperature | −1.146 | 0.683 | −8.019 | 0.000 |

| LTractors | −0.878 | 0.781 | −5.698 | 0.000 |

Note: Critical values were obtained from Mackinnon (1996), where the critical values for the ADF test with intercept are at 5 % significance level.

Table A2-2.

Results of the augmented Dicky– Fuller unit root test in Beheira

| Variable | Level |

First difference |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Prob | Statistic | Prob | |

| LAgricultural Revenue | 0.210 | 0.969 | −4.956 | 0.000 |

| lCropland Area | −2.629 | 0.099 | −4.896 | 0.000 |

| LEmployment in Agriculture | −2.939 | 0.053 | −8.211 | 0.000 |

| LIrrigation Machines | −1.849 | 0.351 | −5.499 | 0.000 |

| LLivestock | −1.064 | 0.717 | −4.614 | 0.001 |

| LPopulation Density | 1.104 | 0.997 | −5.469 | 0.000 |

| lPrecipitation | −4.271 | 0.002 | −5.376 | 0.000 |

| LTemperature | −1.146 | 0.683 | −8.019 | 0.000 |

| LTractors | −0.878 | 0.781 | −5.698 | 0.000 |

Note: Critical values were obtained from Mackinnon (1996), where the critical values for the ADF test with intercept are at 5 % significance level.

Table A2-3.

OLS Estimation Results: D(LAGRICULTURAL REVENUE)

| Region | Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | T-statistics | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandria | DLCA | 0.025 | 0.071 | 0.347 | 0.732 |

| DLEMP | 0.191∗ | 0.065 | 2.962 | 0.008 | |

| DLPOPD | −1.640 | 1.772 | −0.926 | 0.367 | |

| DLIRR | 0.172 | 0.113 | 1.513 | 0.148 | |

| DLIRRM | 0.136 | 0.125 | 1.091 | 0.289 | |

| DLLS | 0.483∗ | 0.136 | 3.559 | 0.002 | |

| DLPRC | 0.016 | 0.041 | 0.388 | 0.702 | |

| DLPRC^2 | −0.002 | 0.018 | −0.113 | 0.911 | |

| DLTEMP | −1.105 | 0.988 | −1.118 | 0.278 | |

| DLTEMP^2 | −32.411∗∗ | 15.192 | −2.133 | 0.047 | |

| DLTractors | 0.538 | 0.300 | 1.789 | 0.090 | |

| Constant | 0.039 | 0.059 | 0.661 | 0.517 | |

| R-Squared | 0.64 | ||||

| Beheira | DLCA | 0.031 | 0.195 | 0.157 | 0.877 |

| DLEMP | −0.034 | 0.061 | −0.553 | 0.587 | |

| DLPOPD | 1.411 | 2.921 | 0.483 | 0.635 | |

| DLIRR | 0.057 | 0.118 | 0.484 | 0.634 | |

| DLIRRM | −0.043 | 0.035 | −1.203 | 0.245 | |

| DLLS | 0.327∗∗∗ | 0.161 | 2.036 | 0.057 | |

| DLPRC | 0.053 | 0.097 | 0.544 | 0.593 | |

| DLPRC^2 | 0.154 | 0.298 | 0.518 | 0.612 | |

| DLTEMP | −0.891 | 0.609 | −1.459 | 0.162 | |

| DLTEMP^2 | 2.128 | 4.346 | 0.489 | 0.630 | |

| DLTractors | −0.198∗∗ | 0.092 | −2.161 | 0.044 | |

| Constant | 1.823 | 0.851 | 2.142 | 0.046 | |

| R-Squared | 0.44 |

Note: Significant coefficients are in bold.