Abstract

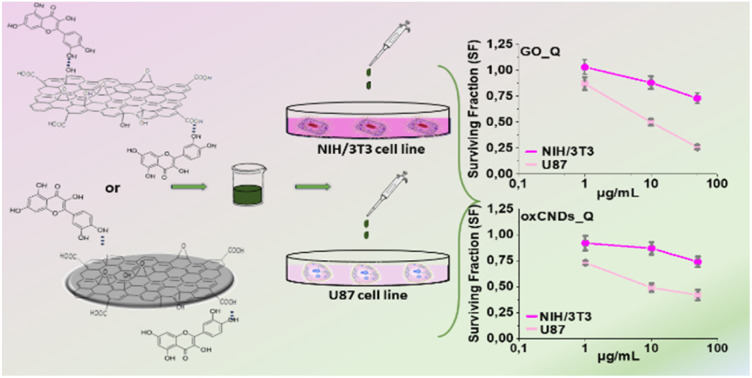

Targeting cancer cells without affecting normal cells poses a particular challenge. Nevertheless, the utilization of innovative nanomaterials in targeted cancer therapy has witnessed significant growth in recent years. In this study, we examined two layered carbon nanomaterials, graphene and carbon nanodiscs (CNDs), both of which possess extraordinary physicochemical and structural properties alongside their nano-scale dimensions, and explored their potential as nanocarriers for quercetin, a bioactive flavonoid known for its potent anticancer properties. Within both graphitic allotropes, oxidation results in heightened hydrophilicity and the incorporation of oxygen functionalities. These factors are of great significance for drug delivery purposes. The successful oxidation and interaction of quercetin with both graphene (GO) and CNDs (oxCNDs) have been confirmed through a range of characterization techniques, including FTIR, Raman, and XPS spectroscopy, as well as XRD and AFM. In vitro anticancer tests were conducted on both normal (NIH/3T3) and glioblastoma (U87) cells. The results revealed that the bonding of quercetin with GO and oxCNDs enhances its cytotoxic effect on cancer cells. GO-Quercetin and oxCNDs-Quercetin induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in U87 cells, whereas oxCNDs caused G2/M arrest, indicating a distinct mode of action. In long-term survival studies, cancer cells exhibited significantly lower viability than normal cells at all corresponding doses of GO-Quercetin and oxCNDs-Quercetin. This work leads us to conclude that the conjugation of quercetin to GO and oxCNDs shows promising potential for targeted anticancer activity. However, further research at the molecular level is necessary to substantiate our preliminary findings.

Graphene oxide and oxidized carbon nanodiscs have been utilized as potential nanocarriers of quercetin. The conjugation of quercetin to these nanomaterials further enhanced the cell cycle arrest effects.

1. Introduction

Precision targeting of cancer cells while preserving normal tissue integrity presents a formidable hurdle. Nevertheless, the adoption of cutting-edge nanomaterials in targeted cancer therapy has experienced notable advancements in recent years.1–3 Moreover, select modification strategies have demonstrated efficacy in augmenting the accumulation of nanodrugs specifically within tumor microenvironments.4,5 The field of biomedicine underwent a significant transformation with the discovery of carbon-based nanomaterials. Among these materials, graphene has found extensive use in various applications, including biosensing,6 drug delivery,7 and chemotherapy,8 experiencing a remarkable surge in utilization over the last decade. Despite possessing unique characteristics such as high surface area, excellent mechanical strength, great biocompatibility, and easy modification, graphene still has some limitations. Notably, it was initially insoluble in water; however, this drawback was overcome with the development of graphene's functional derivatives, such as graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO). GO is produced through the oxidation of graphene, resulting in the addition of several functional groups, such as hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups, which make graphene water soluble, thus enhancing its biocompatibility and bioavailability.9

GO has proven to be advantageous in the development of various biosensors, including Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (LDI-MS), and electrochemical biosensors.10 In the field of regenerative medicine, GO has been extensively studied for its potential use as a scaffold for nerve regeneration,11,12 muscle tissue engineering, and bone restoration.12 Like other graphene-based materials, GO also exhibits antibacterial properties, leading to bacterial death through various mechanisms. These mechanisms include damaging bacterial membranes with its sharp edges, inducing oxidative stress by generating excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), potentially affecting DNA and mitochondria, and ultimately inhibiting bacterial growth. Recent studies have also suggested the entrapment of bacteria within GO sheets as another possible antibacterial mechanism.13,14

The development of GO has also opened up new avenues in drug delivery systems (DDSs). Its large surface area and functional groups enable easy conjugation with other biomolecules, making it an ideal candidate for targeted and tissue-specific drug delivery.15 Lately, GO has been extensively studied as a nanocarrier, particularly for chemotherapy drugs, showing promise in enhancing drug efficiency while minimizing their toxicity.16–22 Additionally, studies suggest the use of GO in controlled drug delivery platforms, allowing for effective on-demand release of drugs when needed.23,24

In contrast to graphene and GO, carbon nanodiscs (CNDs) represent a very close relative to graphite synthesized via the so-called pyrolytic Kværner Carbon Black & H2 (CB & H) process,25,26 leading to disc-like ultra-thin, quasi-two-dimensional particles of sizes ranging between a few nanometers to several micrometers. Alongside the 2-D discs carbon cones of similar size may co-exist. The properties of this new allotrope of graphite are under investigation; however, at first glance the main difference from graphene is the shape, and thus it is important to explore the properties of CNDs as a promising nano-template for biomedical applications. Similarly, oxidized carbon-nanodiscs (oxCNDs) have emerged as potential alternatives for GO. However, to date, their potential as a material for various applications has remained understudied.

As CNDs and oxCNDs possess extremely appealing physicochemical properties (biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, chemical stability, electroconductivity, high reactivity, surface functionality, and low toxicity),27 more research on this aspect is necessary to explore their use in biomedical applications. In this study, we aimed to compare GO and oxCNDs as carriers of quercetin, a potent flavonoid found mainly in vegetables and fruits, which is characterized by its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-hypertensive, and anti-cancer properties.28 To that end, we designed an in vitro study utilizing a normal and a cancer cell line and compared the cytotoxic activity of pristine GO and oxCNDs as well as GO and oxCNDs conjugated with quercetin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials, chemicals and reagents

The graphite, C (purum, powder) and the pristine carbon nanodiscs (CNDs) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Strem Chemicals, Inc. (France), respectively. For the modified Staudenmaier's oxidation procedure two chemicals, 65% nitric acid (HNO3) and 95–97% sulfuric acid (H2SO4), which were supplied by Merck and one reagent, potassium chlorate, which was purchased from Alfa Aesar, were used.

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium High glucose, Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS), thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate, ≥97% (DCFDA), and crystal violet were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from PAN BIOTECH (Aidenbach, Germany). Trypsin-EDTA, penicillin-streptomycin and l-glutamine were purchased from Biowest (Riverside, USA). Hanks' Balanced Salt solution (HBSS) was obtained from Biosera (Nuaille, France). FITC Annexin V, Annexin V binding buffer and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from BioLegend Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA).

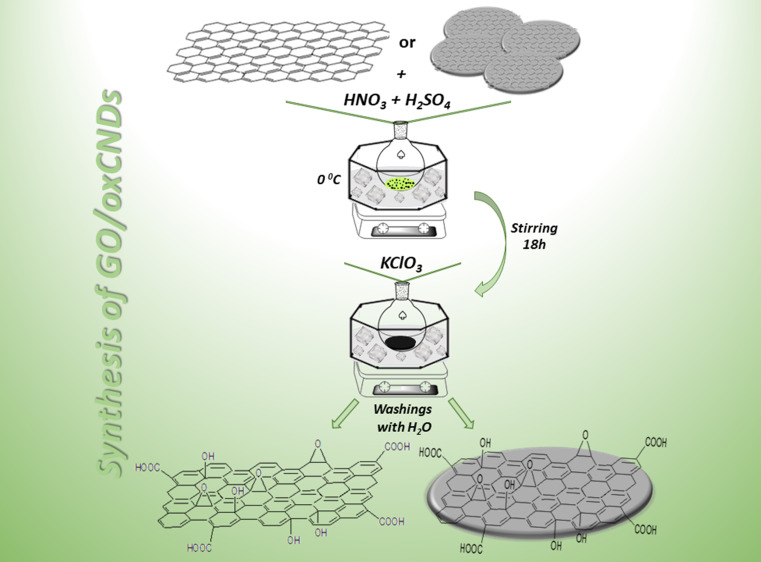

2.2. Oxidation of graphite and CNDs

The oxidation process of C and CNDs was based on a variant of the well-known Staudenmaier's method.29,30 The same chemical procedure was followed for both materials. In a submerged spherical flask in an ice bath (0 °C), 200 mg of carbon material (C or CNDs) were dispersed in a mixture of 8 mL of H2SO4 and 4 mL of HNO3 and stirred for 20 min. After this stage, 4 g of KClO3 were added in small portions and the stirring was continued and completed after 18 h. During the reaction, a thermometer was placed in order to control the temperature. The oxidized products were obtained after several centrifugations and washings with distilled water. The final oxidized product was dried on a glass plate under ambient conditions (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthetic procedures of GO (left) and oxCNDs (right).

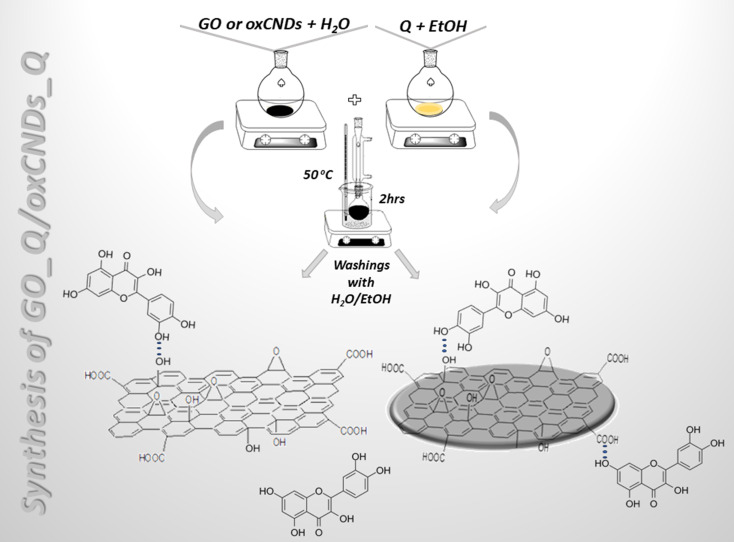

2.3. Decoration of GO and oxCNDs with quercetin

The main goal of this scientific research was the evaluation of two oxidized carbon nanostructures, GO and oxCNDs, as delivery systems of quercetin. The decoration processes for the two materials were similar. 100 mg of oxidized material (GO, oxCNDs) and 88 mg of Q were dispersed in 30 mL H2O and 10 mL EtOH, respectively. Afterwards, the dispersion of Q was added dropwise to that of the carbon material. The suspension was heated at 50 °C for 24 h. At the end of the reaction, the mixture was centrifugated and washed several times with distilled H2O/EtOH (3 : 1). The obtained solid material was dried on a glass plate at room temperature.31 The samples are denoted as GO_Q and oxCNDs_Q (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthetic procedures of GO_Q (left) and oxCNDs_Q (right).

2.4. Cell lines

For the toxicological assessments of nanomaterials, two different cell lines were used. NIH/3T3 a mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line and U87 a cancerous cell line were derived from a human patient with glioblastoma. Both cell lines were grown in high glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, at 37 °C.

2.5. MTT assay

5 × 103 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C). After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the compounds for 24 and 48 h. Cell viability was assessed by adding 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) for 3 h. Formazan that was formed after the addition of MTT was diluted with 100 μL of DMSO. Absorbance was then determined at 570 nm (background absorbance measurement at 690 nm) using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan Spectrum, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.6. Clonogenic assay

1 × 103 cells per well of NIH/3T3 and U87 cells were seeded in 6- well plates and incubated overnight. Treatment with selected doses of nanomaterials was performed to cells for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were incubated for another 7 days. Medium was renewed every two days. On the final day, the cells were stained with a mixture of 0.5% w/v crystal violet, 6% v/v glutaraldehyde and ddH2O. Visible colonies were measured with OpenCFU open-source software (version 3.9.0) (Geissmann, Q. OpenCFU, 2013) and the surviving fraction (SF%) of the treated cells was calculated (Franken, 2006).

2.7. Reactive oxygen species production assay

To assess whether the compounds produce Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), ROS production assay was performed. For this purpose, 15 × 104 cells per well were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated (5% CO2, 37 °C). After 5 h of incubation, treatment with different concentrations of the compounds was performed for 24 h. After treatment, the cells were detached with trypsin and centrifuged for 5 min. Pellets were then resuspended in 2 mL Hanks's balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2.5 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) and were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. Immediately after incubation, samples were put on ice and stained with 1 μg mL−1 PI. ROS production was evaluated directly by flow cytometry.

2.8. Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, 1 × 105 cells per well of both cell lines were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with 10 μg mL−1 of either GO, GO-quercetin, oxCNDs, oxCNDs-quercetin or quercetin for 24 h. Then, the medium was discarded, and the cells were detached with trypsin and centrifuged. Supernatants were discarded and pellets were resuspended with 0.5 mL ice cold PBS. After that, 0.5 mL of absolute ethanol was added to the solution drop by drop, and the samples were kept frozen at −20 °C for 7 days. On the seventh day, the samples were centrifuged, and the pellets were resuspended with 1 mL fresh ice-cold PBS containing PI (25 μg mL−1) and RNAsea (25 μg mL−1) and were incubated for 15 min in the dark. Analysis was performed immediately after incubation by flow cytometry.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate and all data were expressed as mean values +/− standard deviation. Student t-test was conducted to determine the statistically significant difference between the mean values. One-way ANOVA was applied to compare the effects of the quercetin, pristine compounds and quercetin-conjugated materials on NIH/3T3 and U87 cell lines. Values of <0.05 were declared as statistically significant.

2.10. Characterization techniques for GO, GO_Q, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra over the spectra range 400–4000 cm−1 were collected with a PerkinElmer Spectrum GX infrared spectrometer featuring a deuterated triglycine sulphate (DTGS) detector. Every spectrum was the average of 64 scans taken with 2 cm−1 resolution. Samples were prepared as KBr pellets with ca. 2 wt% sample. Raman spectra were recorded with a Micro–Raman system RM 1000 RENISHAW, using a laser excitation line at 532 nm (Nd – YAG), in the range of 1000–3500 cm−1. A power of 1 mW was utilized with a 1 μm focusing spot to avoid photodecomposition of the samples. The XRD patterns were collected on a D8 Advance Bruker diffractometer by using Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) and a secondary beam graphite monochromator. The patterns were recorded in the 2-theta (2Θ) range from 2 to 80°, in steps of 0.02° and a counting time of 2 s per step. Thermogravimetric measurements were carried out with a PerkinElmer Pyris Diamond TG/DTA. Samples of about 5 mg were heated in air from 25 °C to 900 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1. XPS measurements were applied under ultrahigh vacuum with a base pressure of 4 × 10−9 mbar using a SPECS GmbH instrument equipped with a monochromatic MgKa source (hv = 1253.6 eV) and a Phoibos-100 hemispherical analyzer. The energy resolution was set to 1.18 eV. Recorded spectra were set with an energy step set of 0.05 eV and dwell time of 1 s. All binding energies were referenced with regard to the C 1s core level centered at 284.6 eV. Spectral analysis included a Shirley or Linear background subtraction and peak deconvolution involving mixed Gaussian–Lorentzian functions was conducted with a least squares curve-fitting program (WinSpec, University of Namur, Belgium). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were recorded on silicon wafer substrates using tapping mode with a Bruker Multimode 3D Nanoscope (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural and morphological characterization of GO, GO_Q, oxCNDs and oxCNDs

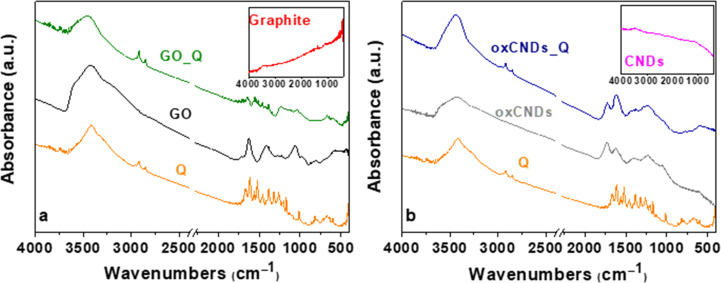

The FTIR spectra of GO and GO_Q are shown in Fig. 1a. For comparison, the spectra of pristine graphite and quercetin are also presented. The spectrum of GO compared with that of graphite presents more intense peaks. The band at 1058 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of C–O groups, while the peak at 1224 cm−1 is associated with the asymmetric stretching of C–O–C bridges in epoxy groups and/or to the deformation vibrations of O–H in the carboxylic acid groups. The peak at 1412 cm−1 corresponds to the bending vibrations (deformation) of hydroxyl groups. The bands which are located at 1622 and 1711 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the –COOH groups. The intense band at 3421 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl groups. The appearance of the bands which are analyzed above confirms the successful oxidation of the graphite.32 Observing the spectrum of GO_Q, it is shown that there are two peaks, in the range of 2800–3000 cm−1, which do not exist in that of GO. These are attributed to the stretching vibration of alkyl groups of quercetin, which represent a proof that the quercetin's molecules are present on the surface of GO. The other bands of Q are not distinct in the spectrum of GO_Q, due to the overlapping with the functional groups on the surface of GO.

Fig. 1. FTIR spectra of (a) Q, graphite, GO, and GO_Q and (b) Q, pristine CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q.

In Fig. 1b are presented the FTIR spectra of Q, pristine CNDs, oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q. Comparing the spectrum of pristine CNDs and the oxidized ones, the oxCNDs present bands due to the creation of oxygen groups on their graphitic surface. More specifically, the peak at 1054 cm−1 is associated with the stretching vibrations of C–O groups and the band at 1225 cm−1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching of C–O–C bridges in epoxy groups and/or to the deformation vibrations of O–H in the carboxylic acid groups. The band at 1400 cm−1 is assigned to the bending vibrations (deformation) of hydroxyl groups. At 1621 and 1734 cm−1, the peaks that are observed are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the –COOH groups. Finally, the peak at 3433 cm−1 is associated with the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl groups.30 As in the case of GO_Q, the characteristic peaks of alkyl groups appear for oxCNDs_Q at 2849 and 2918 cm−1, confirming the presence of Q on the oxidative surface of oxCNDs. Concerning the Q bands in the spectrum of oxCNDs_Q, the same behavior as GO_Q is observed (explained in detail above).

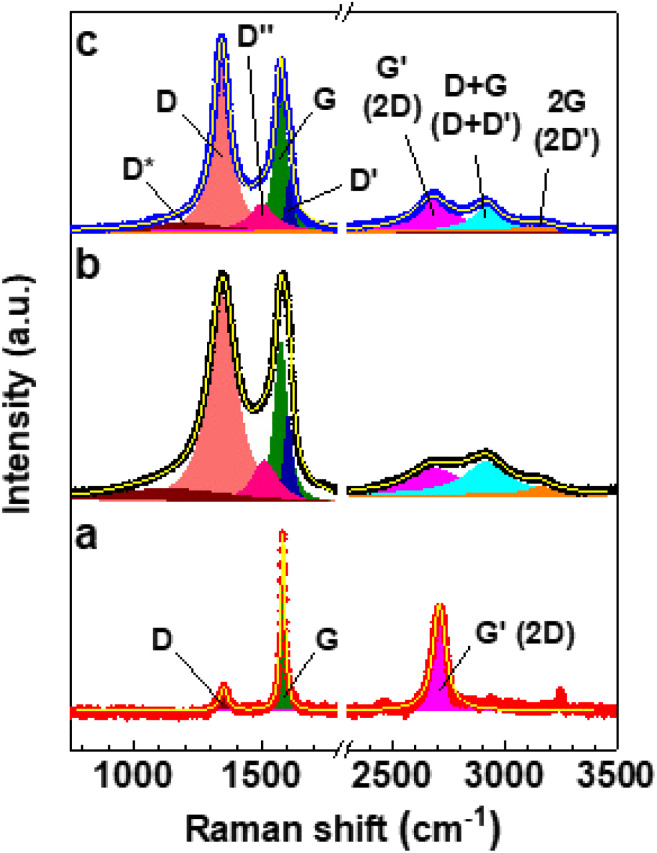

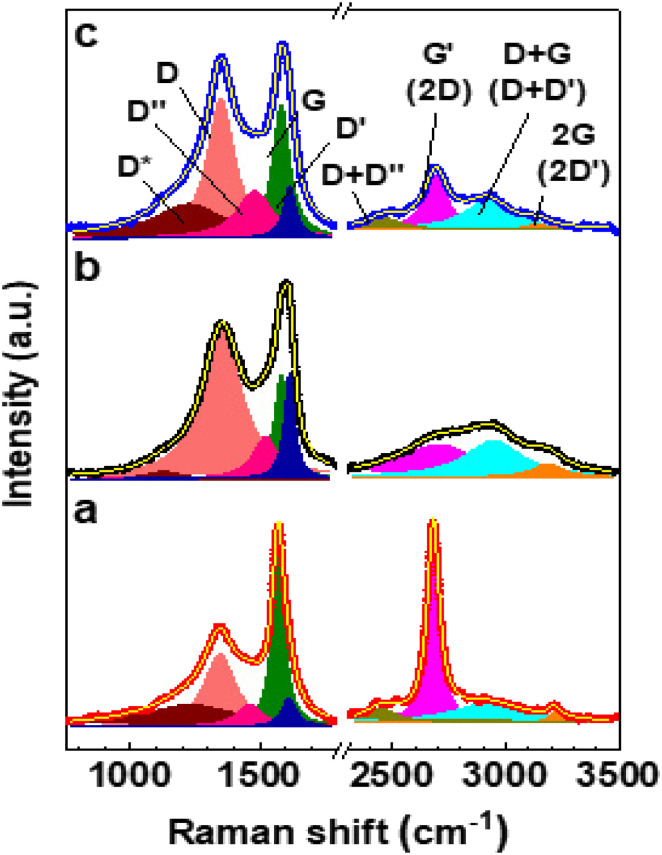

Fig. 2 depicts the Raman spectra of graphite, GO, and GO_Q. The Raman spectrum of graphite reveals intense G and G′ (2D) bands, and a weaker D band. The intense and broad D bands of GO and GO_Q can be attributed to the sp2-to-sp3 hybridization associated with the oxidation of graphite. This is evidenced by the emergence of the D*, D′′, D′, D + G (D + D′), and 2 G (2D′) bands, which are characteristic of GO-based nanomaterials.33,34 These bands were unveiled upon deconvolution, which was achieved by fitting the Raman spectra of GO and GO_Q to eight symmetric Lorentzian peaks as shown in Fig. 2. The Raman spectrum of graphite was fitted to three symmetric Lorentzian peaks corresponding to the D, G, and G′ (2D) bands. The Lorentzian curve fitting parameters for the Raman spectra of graphite, GO, and GO_Q are presented in Tables S1 and S2.†

Fig. 2. Deconvoluted Raman spectra of (a) graphite, (b) GO, and (c) GO_Q. All the bands were fit to Lorentzian profiles.

The D-to-G and D′-to-G band intensity ratios (ID/IG and ID′/IG, respectively) are directly proportional to defect concentration in graphene.35 As can be seen in Table 1, ID/IG and ID′/IG of GO are significantly higher than those of graphite. Furthermore, the G′-to-G band intensity ratio (IG′/IG), which is inversely proportional to defect concentration in graphene,35 decreases by ∼73% upon oxidation of graphite. Therefore, all these observations confirm the oxidation of graphite, which is also corroborated by the broadening of the G and G′ bands of GO relative to those of graphite as revealed by the full width at half maximum (FWHM) values of their respective G and G′ bands (Tables S1 and S2†).36 Interestingly, ID/IG and ID′/IG of GO_Q are respectively ∼6.2% and ∼38% lower than those of GO, whereas IG′/IG is ∼31% higher (Table 1). This can be attributed to the reduction of GO upon the adsorption of quercetin, which is evidenced by the ∼65% increase in the G′-to-D + G band intensity ratio (IG′/ID+G).34

Calculated Raman band intensity ratios for graphite, GO, and GO_Q. For graphite, the values of ID′/IG and IG′/ID+G were assumed to be due to the absence of D′ and D + G (D + D′) bands.

| Sample | I D/IG | I D′/IG | I G′/IG | I G′/ID+G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite | 0.14 | ≈0 | 0.60 | ∞ |

| GO | 1.29 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.81 |

| GO_Q | 1.21 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 1.34 |

Fig. 3 depicts the deconvoluted Raman spectra of CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q. The Raman spectrum of oxCNDs exhibits the same eight characteristic bands of GO, whereas the Raman spectra of CNDs and oxCNDs_Q reveal an additional band at ∼2450 cm−1 corresponding to the D + D′′ band.37 For this reason, each of the Raman spectra of CNDs and oxCNDs_Q was fitted to nine symmetric Lorentzian peaks as shown in Fig. 3. The Lorentzian curve fitting parameters for the Raman spectra of CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q are presented in Tables S3 and S4.† The oxidation of CNDs seems to be remarkably similar to that of graphite. This is evidenced by the (i) significant increase in ID/IG and ID′/IG (Table 2); (ii) ∼72% decrease in IG′/IG (Table 2); (iii) broadening of the G and G′ bands (Tables S3 and S4†); (iv) ∼91% decrease in IG′/ID+G (Table 2). Moreover, the adsorption of quercetin onto oxCNDs seems to promote their reduction as in the case of GO. This is evidenced by the (i) ∼27% and ∼61% decrease in ID/IG and ID′/IG, respectively; (ii) ∼29% increase in IG′/IG; (iii) ∼108% increase in IG′/ID+G (Table 2). It is worth noting that ID/IG, ID′/IG, and IG′/IG of GO_Q and oxCNDs_Q are solely qualitative parameters that cannot be used to quantify the extent of reduction associated with the adsorption of quercetin. This is because quercetin exhibits an intense band at ∼1600 cm−1,38 which overlaps with the G and D′ bands of GO and oxCNDs. This leaves us with IG′/ID+G as the only quantitatively reliable parameter to estimate the extent of quercetin-promoted reduction of GO and oxCNDs.

Fig. 3. Deconvoluted Raman spectra of (a) CNDs, (b) oxCNDs, and (c) oxCNDs_Q. All the bands were fit to Lorentzian profiles.

Calculated Raman band intensity ratios for CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q.

| Sample | I D/IG | I D′/IG | I G′/IG | I G′/ID+G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNDs | 0.42 | 0.17 | 1.11 | 10.24 |

| oxCNDs | 1.42 | 1.01 | 0.31 | 0.89 |

| oxCNDs_Q | 1.04 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 1.85 |

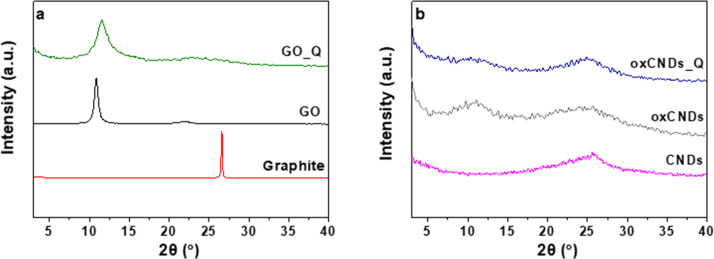

The XRD patterns of graphite, GO and GO_Q are presented in Fig. 4a. Graphite exhibits the characterized reflection 002 at 2θ = 25.60°, while in the pattern of GO the principal reflection 001 appears at 2θ = 10.70°. The interlayer space increased from 3.47 Å to 8.27 Å, which proves the successful creation of oxygen functional groups between the graphene layers. In the case of GO_Q, it is observed that the 001 reflection remains but is presented slightly shifted and broader, which in fact indicates that there is an interaction between the Q and the graphene sheets. In Fig. 4b the pattern of oxCNDs is compared with that of oxCNDs_Q while the corresponding pattern of pristine CNDs is also presented. After the oxidation process the 001 reflection at 10.88° appears and the interlayer space increased from 3.35 Å to 7.66 Å. After the decoration of oxCNDs with Q, the intensity of 001 reflection is reduced, indicating the partially exfoliation of the graphene layers due to the presence of Q.31,39

Fig. 4. XRD patterns of (a) graphite, GO, and GO_Q and (b) pristine CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q.

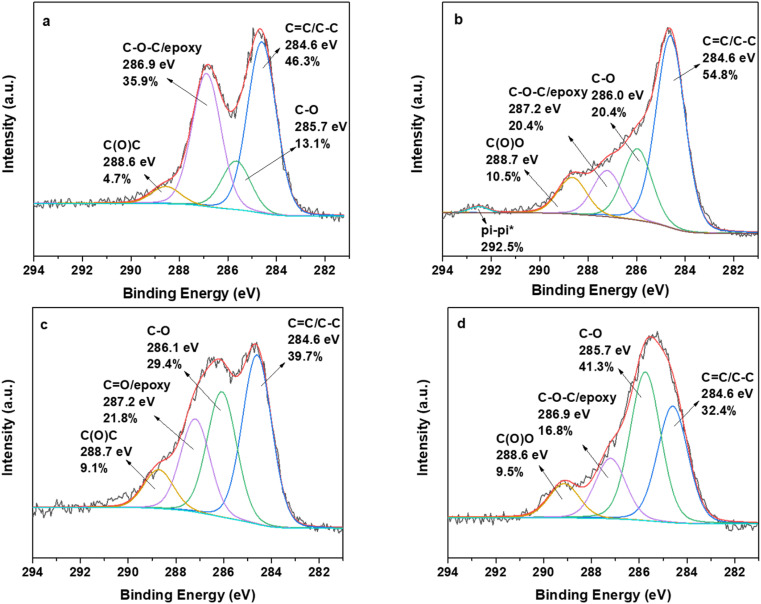

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was employed to investigate the kinds of oxygen functionalities of graphene and CNDs after the oxidation procedure, as well as the types of interactions between the two layered carbon matrices and quercetin. Fig. 5a (GO) and Fig. 5c (oxCNDs) display the C 1s photoelectron peak of GO and oxCNDs. For GO we detect the main aromatic frame at 284.6 eV accounting for 46.3% of the whole carbon peak, while at 285.7 eV is due to the C–O functionalities (13.1%). A very intense peak centered at 286.9 eV is responsible for the C–O–C and epoxy groups and is estimated to be 35.9% of the carbon 1s peak. Finally, a weak peak (4.7%) is due to the carboxyl end groups. The atomic percentage of carbon and oxygen is estimated to be 73.1% for carbon and 26.8% for oxygen.40 The respective results we obtain for oxCNDs are shown in Fig. 5c. The main difference compared to the C 1s peak of GO lies in the fact that the amount of C–O functional groups is higher for oxCNDs (29.4%), and the amount of epoxy groups is lower for oxCNDs (21.8%). After the adsorption of quercetin, the C 1s photoelectron peak is presented in Fig. 5b (GO_Q) and Fig. 5d (oxCNDs_Q). There are main differences that indicate the existence of quercetin on the surface of GO. In detail, we detect the main C–C/C C peak at 284.6 eV, which fills 54.8% of the whole carbon peak, while the C–O peak is increased (20.4%) and slightly shifted at 286.0 eV. This sub-electronvolt shift may be attributed to the weak interaction (Van Der Waals) of quercetin with the hydroxyl groups of GO, while the increase in the amount is due to the rich C–OH environment of the drug. At 287.2 eV, we detect the peak assigned to the C O groups of quercetin and epoxy groups. It is noteworthy to state here that the aforementioned peak dramatically decreased from 35.9% to 13.2%. Taking into account the extra C O groups from the drug, we propose that quercetin may reduce the epoxy groups of GO acting as a reducing agent. These results are in accordance with Raman spectroscopy, indicating that antioxidant drugs (such as quercetin) play the role of a reducing agent as well. The next peak at 288.7 eV is attributed to the carboxyl groups and is increased compared to GO estimated to be 10.5%. A very intriguing observation is a fitted peak at very high binding energies (292.5%), and this is due to the pi–pi* interactions between the aromatic groups of quercetin and graphene, denoting a second type of interaction. For oxCNDs, we do not detect any pi–pi* interactions assuming that there is only one type of interaction between quercetin and nanodiscs from the sub-electronvolt shift on the C–O and epoxy groups Fig. 5d.

Fig. 5. C 1s photoelectron spectra of (a) GO, (b) GO_Q, (c) oxCNDs and (d) oxCNDs_Q.

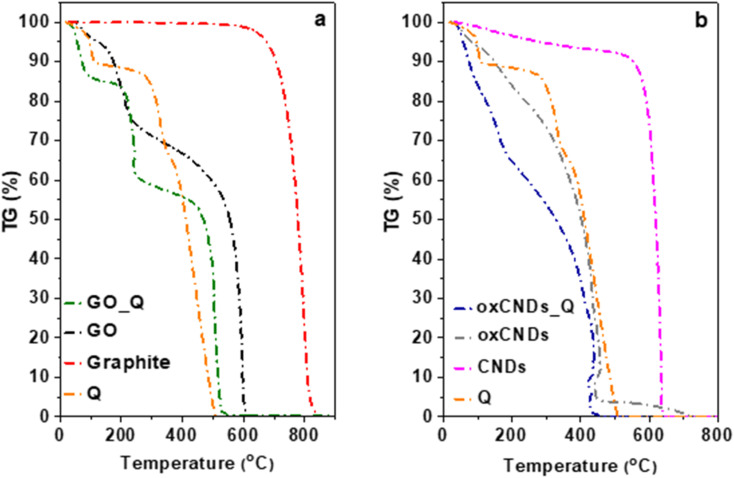

The thermogravimetric analyses of the initial (GO and oxCNDs) and decorated materials with quercetin (GO_Q and OxCNDs_Q) are presented in Fig. 6. For comparison reasons, the thermographs of graphite, pristine CNDs and quercetin are also shown. In Fig. 6a, the curve of GO presents three weight losses. More specifically, the initial mass loss (∼4%) takes place up to 100 °C, which is attributed to the removal of the water molecules. The following mass loss up to 420 °C (∼29%) corresponds to the removal of functional oxygen groups. The decomposition of the graphitic lattice constitutes the third combustion stage, which is followed by ∼67% weight loss. In the case of GO_Q, between 100 °C and 400 °C the curve exhibits a mass loss of ∼30%, caused by the removal of both the functional groups and the main organic compound. The combustion of the graphitic lattice takes place at approximately 400 °C, which is followed by ∼55% mass loss. Up to 100 °C, a weight mass loss of 15% is observed, which is attributed to the removal of the naturally adsorbed water molecules. This value is higher than that of GO because of the hydrophilicity of Q. In Fig. 6b, the analysis of oxCNDs indicates the existence of three mass losses. Up to 120 °C, the initial weight loss corresponds to the removal of the naturally adsorbed water molecules and the percentage was estimated to be ∼8 wt%. In the temperature range between 120 and 320 °C, a mass loss of 22% is observed which can be attributed to the decomposition of the oxygen containing groups. Upon heating, the deformation of the carbon network takes place (∼80%). Analyzing the oxCNDs_Q thermograph, between 120 and 300 °C, a weight loss in the order of 27% wt. is observed, which corresponds to the removal of both the oxygen functional groups and the main organic compound. The deformation of the graphitic lattice takes place at approximately 300 °C, which is followed by ∼53% mass loss. Up to 120 °C, a mass loss of 20% is observed, which corresponds to the removal of the water molecules. The higher percentage of the water molecules in oxCNDs_Q comparing to oxCNDs is attributed to the hydrophilic character of Q.

Fig. 6. TGA thermographs of (a) Q, graphite, GO, and GO_Q and (b) Q, pristine CNDs, oxCNDs, and oxCNDs_Q.

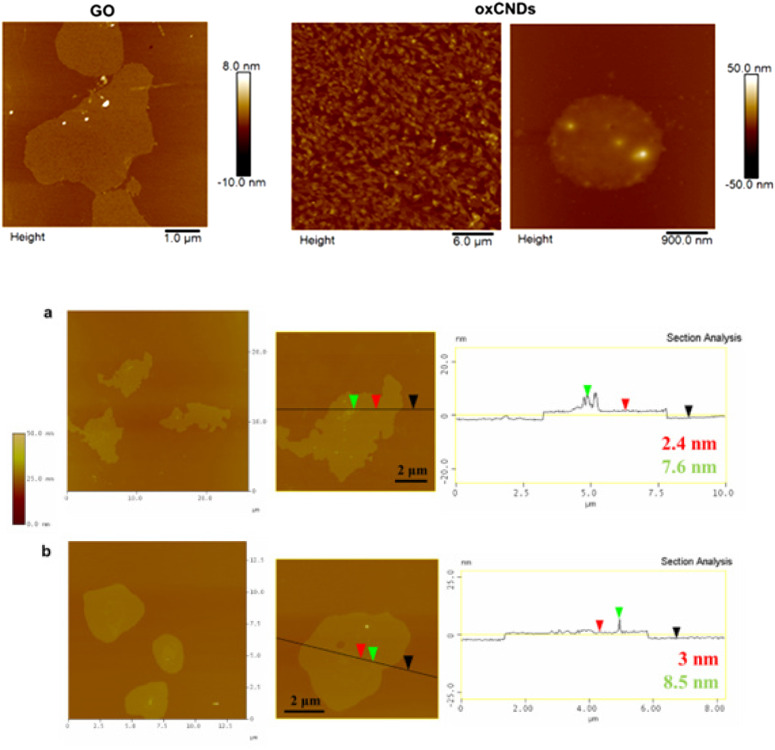

The representative AFM images of GO and oxCNDs deposited onto Si wafers from aqueous dispersions are shown in Fig. 7a. The average thickness of the oxidized carbon allotropes is 2 ± 1 nm, demonstrating single or few layer structures. Similar morphological characteristics are observed after the incorporation of quercetin as depicted in Fig. 7b. The AFM images of GO_Q and oxCNDs_Q hybrids show the presence of relatively uniform particles decorating several micrometer-sized layers, indicative of the successful attachment of relatively small aggregates of quercetin molecules on the surface of GO and oxCNDs. The average size of the quercetin molecules was about 7.5 ± 1 nm in both samples, while the thickness of graphenic layers was 3 ± 0.5 nm as determined from the cross-sectional analysis, corresponding to a stacking of very few graphene layers.

Fig. 7. (a) AFM height images of GO and oxCNDs. (b) AFM height images and cross section analysis of the GO and oxCND nanostructures chemically modified with quercetin molecules.

3.2. In vitro toxicity against NIH/3T3 and U87 cells

3.2.1. Toxicity evaluation of quercetin against NIH/3T3 and U87 cells

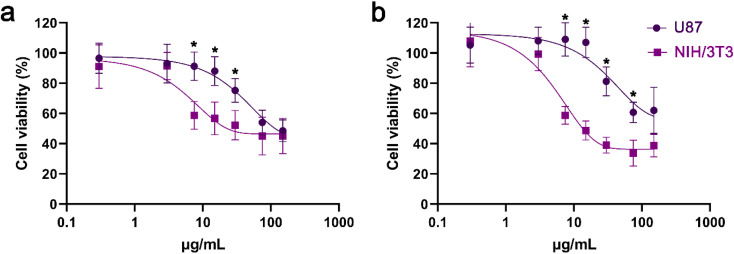

Firstly, we examined the cytotoxicity of quercetin against NIH/3T3 and U87 cells using MTT assay. Quercetin was tested in a wide range of doses, ranging from 0.3 to 150 μg mL−1. In both cell lines, quercetin induced dose-dependent toxicity. Treatment with low doses (below 7.5 μg mL−1) of quercetin for both 24 and 48 h exerted a similar effect in both cell lines. However, at doses higher than 7.5 μg mL−1, quercetin was found to be more toxic to NIH/3T3 cells than to U87 cells (Fig. 8). Exposure of NIH/3T3 and U87 cells to the maximum dose of 150 μg mL−1 resulted in a 60% and 40% decline in cell viability, respectively.

Fig. 8. Cell viability of NIH/3T3 and U87 cells after treatment with Q for (a) 24 and (b) 48 h. *, statistically significant difference between U87 and NIH/3T3 cells, p < 0.05.

3.2.2. Toxicity evaluation of GO and GO-Q against NIH/3T3 and U87 cells

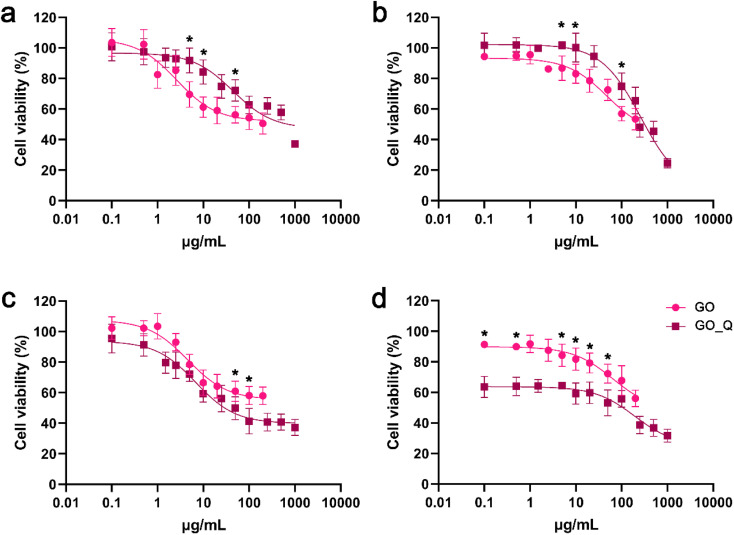

GO was tested over a range of 0.1–200 μg mL−1, while GO_Q was tested in a higher range of doses (0.1–1000 μg mL−1) to account for the percentage of quercetin bound to the GO nanoparticles.

In NIH/3T3 cells, both GO and GO_Q induced dose-dependent toxicity rather than time-dependent toxicity. However, cell viability was higher in cells treated with GO_Q for doses up to 100 μg mL−1 (Fig. 9a and b). In U87 cells, GO had a similar effect to that observed in NIH/3T3 cells. Conversely, GO_Q exerted a potent cytotoxic effect, and time-dependent toxicity was evident even at low doses. At 24 h, viability ranged between 70 and 90% up to a dose of 5 μg mL−1 and then gradually decreased to 60–40% at doses up to 1000 μg mL−1 (Fig. 9c). At 48 h, viability was relatively low even at the starting dose of 0.1 μg mL−1 (with 60–65% of cells remaining viable) and continued to decline, reaching 30–40% at higher doses (250–1000 μg mL−1) (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 9. Cell viability of NIH/3T3 (a and b) and U87 cells (c and d) after treatment with GO or GO_Q for 24 (a and c) and 48 h (b and d). *, statistically significant difference between GO and GO_Q at the corresponding concentrations, p < 0.05.

The cytotoxic effect of GO appears to vary depending on the cell type. Jaworski et al. conducted an investigation on U87 and U118 cells using XTT assay, reporting dose-dependent toxicity in both cell lines. They observed a 30% decrease in cell viability after 24 h of GO exposure.41 However, in human bone marrow stromal cells (HS-5 cells), GO doses up to 100 μg mL−1 were found to be nontoxic, and cell viability remained similar to the control after 24 h.42 Additionally, GO at 125 μg mL−1 did not significantly affect L929 and BT474 cell viability, with both cell lines exhibiting over 70% viability after 48 h of exposure. However, at 250 μg mL−1, only 50% of the L929 cells were able to survive. The same authors created GO nanocarriers loaded with different concentrations (2.5% and 5% w/v) of quercetin (GO_Q) and tested their biocompatibility. GO_Q 2.5% w/v induced a significant drop in the viability of both cell lines. On the other hand, GO_Q 5% w/v showed biocompatibility with fibroblasts and only exhibited slight cytotoxicity at higher doses in BT474 cells.43 This finding aligns with our study, although we observed a more potent cytotoxic effect towards cancer cells across a wider range of GO_Q doses.

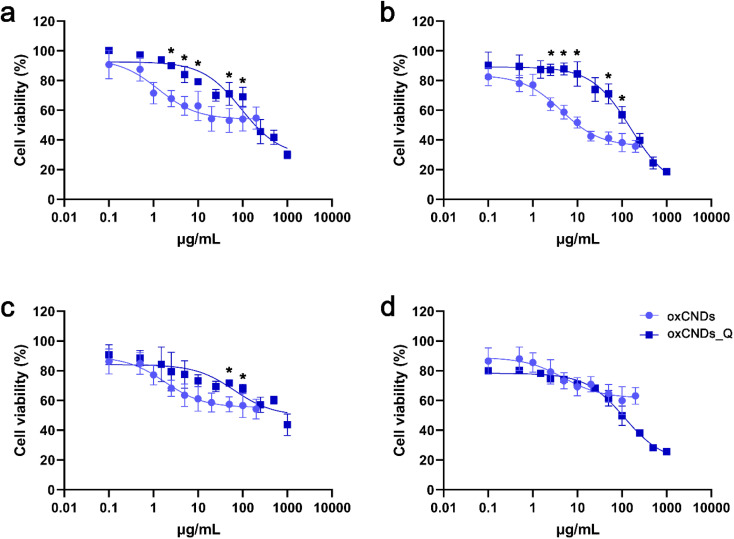

3.2.3. Toxicity evaluation of oxCNDs and oxCNDs-Q

In NIH/3T3 cells, oxCNDs exhibited dose-dependent toxicity with mild time-dependent effects. Cell viability at 24 h started at 90% for the lowest dose (0.1 μg mL−1) and decreased to 55% at the highest dose (200 μg mL−1). Similarly, at 48 h, cell viability started at 80% for the lowest dose and declined to 35% at 200 μg mL−1 (Fig. 10a and b). Up to a dose of 100 μg mL−1, oxCNDs_Q were found to be less toxic than oxCNDs in NIH/3T3 cells. Specifically, cell viability ranged between 70 and 90% for both 24 and 48 h, and then it decreased rapidly at higher doses.

Fig. 10. Cell viability of NIH/3T3 (a and b) and U87 cells (c and d) after treatment with oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q for 24 (a and c) and 48 h (b and d). *, statistically significant difference between oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q at the corresponding concentrations, p < 0.05.

In U87 cells, treatment with oxCNDs for 24 h displayed a dose-dependent effect. Cell viability remained high (70–80%) at low doses (0.1–2.5 μg mL−1) and then decreased to 55–65% at all doses up to 200 μg mL−1. For 24 h, oxCNDs_Q were less toxic than oxCNDs at all tested doses up to 100 μg mL−1 (Fig. 10c). However, at 48 h, both materials had almost the same effect in U87 cells, with viability values starting at 80% for the lowest dose (0.1 μg mL−1) and declining to 50% at 100 μg mL−1. Notably, at the highest dose of 1000 μg mL−1, oxCNDs_Q exhibited a significant toxic effect, with only 25% of cells remaining alive (Fig. 10d).

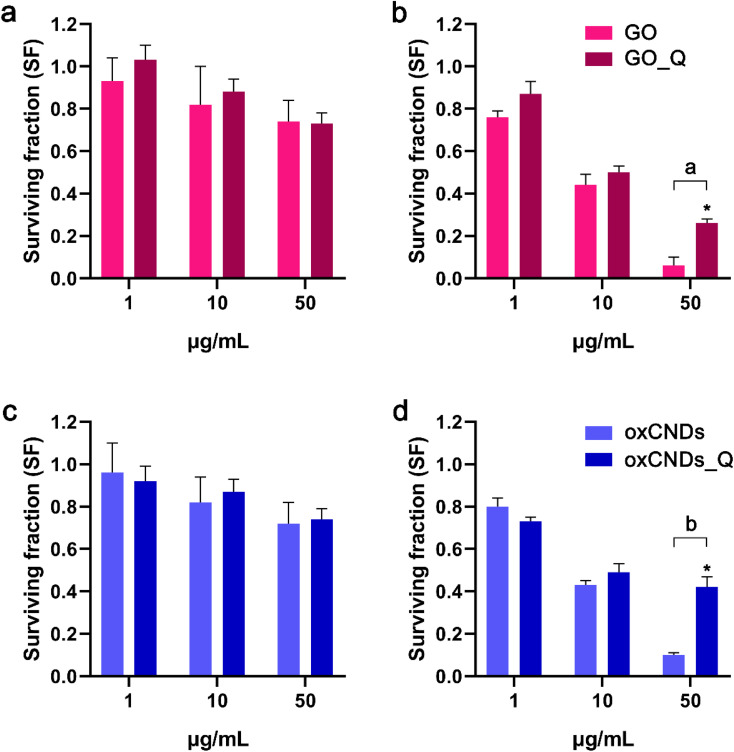

3.3. Ability of NIH and U87 cells to form colonies after treatment with GO, GO-Q, oxCNDs or oxCNDs-Q

Treatment with GO, GO_Q, oxCNDs, or oxCNDs_Q for 24 h showed a similar effect on NIH/3T3 cells. At the maximum tested dose of 50 μg mL−1, all materials resulted in a 30% reduction in cell viability (Fig. 11a and c). In U87 cells, the cytotoxic effect of the materials was more potent, and their ability to form colonies was dramatically decreased even after exposure to 10 μg mL−1. Interestingly, at the highest dose of 50 μg mL−1, the survival fraction for quercetin-conjugated materials was higher compared to the corresponding pristine compounds (Fig. 11b and d). Possibly, the pristine compounds induce greater damage than quercetin-conjugated materials, leading to the activation of apoptotic pathways and reduced long-term cell survival. Additionally, the interaction between pristine compounds and free quercetin (potentially released from quercetin-conjugated materials) may contribute to this outcome, necessitating further investigation.

Fig. 11. Clonogenic assay in NIH/3T3 (a and c) and U87 cells (b and d) after incubation with increasing doses of GO and GO_Q (a and b) or oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q (c and d) for 24 h. *, statistically significant difference between GO_Q and oxCNDs_Q, p < 0.05; a, statistically significant difference between GO and GO_Q, p < 0.05; b, statistically significant difference between oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q, p < 0.05.

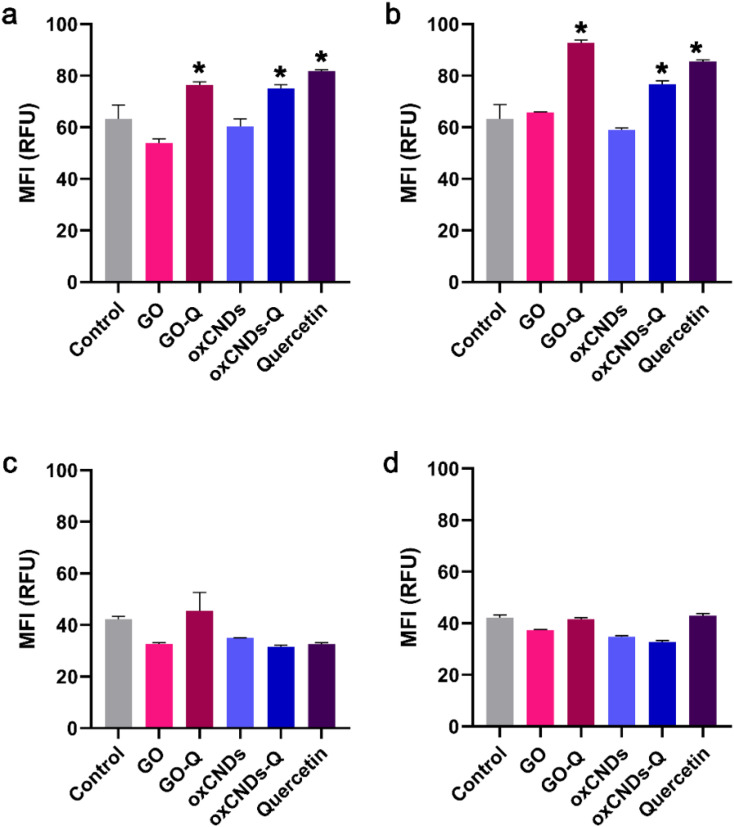

3.4. Intracellular ROS production in NIH/3T3 and U87 cells

Initial intracellular ROS levels were found to be higher in NIH/3T3 cells compared to U87 cells. When exposed to 1 or 10 μg mL−1 quercetin, only NIH/3T3 cells exhibited an increase in ROS levels. However, the pristine materials (GO and oxCNDs) did not interfere with the ROS status in either NIH/3T3 or U87 cells. On the other hand, quercetin-conjugated nanomaterials (GO_Q and oxCNDs_Q) led to the production of ROS in NIH/3T3 cells. At a dose of 1 μg mL−1, GO_Q induced a 13% increase in ROS production (p < 0.05), while oxCNDs_Q and quercetin caused an increase of 12% and 18%, respectively (p < 0.05) (Fig. 12a). Notably, for GO_Q, the elevation of ROS was dose-dependent, with a 30% higher ROS formation compared to the control at a dose of 10 μg mL−1 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 12b). Interestingly, in U87 cells, none of the nanomaterials induced a statistically significant elevation in ROS formation at the doses of 1 or 10 μg mL−1 (Fig. 12c and d). Additionally, Pelin et al. demonstrated in their study that GO induces a dose- and time-dependent ROS formation in HaCaT keratinocytes. Exposure of HaCaT cells to a higher GO dose (100 μg mL−1 for 24 h) than those used in our study (1 and 10 μg mL−1) resulted in a 33% increase in ROS production.44

Fig. 12. ROS production in NIH/3T3 (a and b) and U87 cells (c and d) after treatment with either 1 μg mL−1 (a and c) or 10 μg mL−1 (b and d) of GO, GO_Q, oxCNDs, oxCNDs_Q or quercetin alone, for 24 h. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. RFU, relative fluorescence units. *, statistically significant difference from the control, p < 0.05.

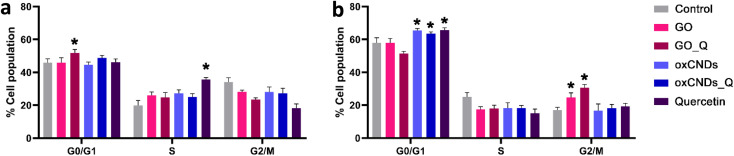

3.5. Cell cycle arrest

Quercetin treatment caused a significant increase in the S-phase of NIH/3T3 cells (control: 19.9% ± 3.0%, quercetin: 35.7% ± 1.1%, and p < 0.05) (Fig. 13a) and in the G0/G1 phase of U87 cells (control: 58.0% ± 3.0%, quercetin: 65.7 ± 1.4%, and p < 0.05) (Fig. 13b). Interestingly, only GO-Q induced cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase of NIH/3T3 cells (control: 45.9% ± 2.3%, GO_Q: 51.8% ± 2.1%, and p < 0.05) (Fig. 13a). In a previous study, micro-GO (mGO) and nano-GO (nGO) also induced cell cycle arrest in the S-phase of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) at tested doses of 100 and 200 μg mL−1. This increase in the cell population in the S-phase was also dose-dependent and correlated with an increase in intracellular ROS production.45

Fig. 13. Cell cycle arrest in NIH/3T3 (a) and U87 cells (b), after treatment with 10 μg mL−1 of each nanocompound for 24 h. *, statistically significant difference from the control, p < 0.05.

In U87 cells, oxCNDs and oxCNDs_Q induced cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase (control: 58.0% ± 3.0%, oxCNDs: 65.5% ± 1.1%, oxCNDs_Q: 63.6% ± 1.0%, and p < 0.05), while GO and GO-Q caused an 8% and 14% increase in the G2/M phase, respectively (control: 17.0% ± 1.8%, GO: 24.6% ± 2.9%, GO-Q: 30.6% ± 2%, and p < 0.05) (Fig. 13b). It is worth noting that Wang et al. did not observe any cell cycle alterations in U87 or U251 cells after treatment with 50 μg mL−1 of GO, which differs from our results.46

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed two layered carbon nanomaterials, namely GO and oxCNDs, as nanocarriers for quercetin. While quercetin alone exhibited limited cytotoxicity against cancer glioblastoma cells (U87) and higher toxicity against normal cells (NIH/3T3), likely due to excessive ROS generation, its conjugation with graphene oxide (GO) and oxidized carbon nanodots (oxCNDs) resulted in two novel hybrid systems that showed increased toxicity against cancer cells compared to normal cells. While quercetin alone showed limited cytotoxicity against cancer glioblastoma cells (U87), its conjugation with GO and oxCNDs resulted in two novel hybrid systems exhibiting higher toxicity against cancer cells compared to normal cells. Importantly, none of these compounds induced the generation of ROS. Specifically, GO induced G0/G1 arrest in U87 cells, while oxCNDs caused G2/M arrest. The conjugation of quercetin to these nanomaterials further enhanced the cell cycle arrest effects. Moreover, in long-term survival studies, cancer cells showed significantly lower viability than normal cells at all corresponding doses. This work represents a significant advancement in the development of nanomaterials capable of targeting cancer cells while minimizing impacts on normal cells. To gain a deeper understanding of the anticancer properties of these promising nanocompounds, further research is warranted. Specifically, in-depth analysis of signal transduction pathways, with a focus on apoptosis, studies on endocytosis mechanisms, and investigations into potential damages on cell membranes, will provide valuable insight.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: P. Z., K. S., Y. V. S., and V. R.; methodology: P. Z., G. T., M. A. and A. M. A.; validation: P. Z., K. S., Y. V. S., M. S., A. K., A. K. and K. T.; data curation: P. Z., K. S., M. S., A. K., A. K. and G. A.; formal analysis resources: P. V., K. T. and D. P.; writing–original draft preparation: P. Z., K. S., M. S., E. P., G. T. and Y. V. S.; writing–review and editing: P. Z., K. S., Y. V. S., K. T., P. V., E. P. and D. P. G.; visualization: K. T., E. P., P. V. and Y. V. S.; supervision: K. T. and V. R. and D. P. G.; project administration: Y. V. S. and D. P. G.; funding acquisition: V. R., D. P. and D. P. G.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Note added after first publication

This article replaces the version published on 17th April 2024, which contained errors in Scheme 1, Scheme 2, Figure 1 and Figure 4.

Supplementary Material

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3na00966a

References

- Chu Z. Chen H. Wang P. Wang W. Yang J. Sun J. Chen B. Tian T. Zha Z. Wang H. Qian H. ACS Nano. 2022;16:4917–4929. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c00854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. Zhang C. Wang W. Chu Z. Zha Z. He X. Zhou W. Liu T. Wang H. Qian H. ACS Nano. 2020;14:14919–14928. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c04370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Chu Z. Yang J. Qian H. Xu J. Chen B. Tian T. Chen H. Xu Y. Wang F. ACS Nano. 2022;16:15471–15483. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c08013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan J. Liu H. Chen B. Wang F. Wang W. Zha Z. Qian H. Miao Z. Sun J. Tian T. He Y. Wang H. ACS Nano. 2021;15:11428–11440. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c01077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. Xiao L. Wang W. Xu L. Jiang Y. Zhang G. Liu L. Li X. Yu Y. Qian H. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15:33903–33915. doi: 10.1021/acsami.3c06838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou E. Simos Y. V. Spyrou K. Tzianni E. I. Vezyraki P. Tsamis K. Patila M. Tigas S. Prodromidis M. I. Gournis D. P. Stamatis H. Peschos D. Dounousi E. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023;248:14–25. doi: 10.1177/15353702221134105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jampilek J. Kralova K. Materials. 2021;14:1059. doi: 10.3390/ma14051059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo-Diogo D. Lima-Sousa R. Alves C. G. Costa E. C. Louro R. O. Correia I. J. Colloids Surf., B. 2018;171:260–275. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimiev A. M. and Eigler S., Graphene Oxide: Fundamentals and Applications, Wiley, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Kim J. Kim S. Min D.-H. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016;105:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y. Park J. Sim S. H. Sung M. G. Kim K. S. Hong B. H. Hong S. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:H263–H267. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleki M. Zarezadeh R. Nouri M. Sadigh A. R. Pouremamali F. Asemi Z. Kafil H. S. Alemi F. Yousefi B. Biomol. Concepts. 2020;11:182–200. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2020-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi S. KrishnaRao Eswar N. Singh S. A. Chatterjee K. Madras G. Sood A. K. RSC Adv. 2016;6:1231–1242. doi: 10.1039/C5RA19925E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P. Huo P. Zhang R. Liu B. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:737. doi: 10.3390/nano9050737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. Bytesnikova Z. Ashrafi A. M. Adam V. Richtera L. Processes. 2020;8:1636. doi: 10.3390/pr8121636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shim G. Kim M. G. Park J. Y. Oh Y. K. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016;105:205–227. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseini-Ghahfarokhi M. Mirkiani S. Mozaffari N. Abdolahi Sadatlu M. A. Ghasemi A. Abbaspour S. Akbarian M. Farjadian F. Karimi M. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:9469–9496. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S265876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Chen L. Shen B. Chen L. Mo J. Feng J. Langmuir. 2019;35:6120–6128. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L. Li G. Lu T. Wei Y. Nong Z. Wei M. Pan X. Qin Q. Meng F. Li X. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021;110:3631–3638. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Wang Y. Du J. Wang X. Duan A. Gao R. Liu J. Li B. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1725. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keklikcioglu Cakmak N. Eroğlu A. Polym. Bull. 2022;80:2171–2185. doi: 10.1007/s00289-022-04549-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giusto E. Žárská L. Beirne D. F. Rossi A. Bassi G. Ruffini A. Montesi M. Montagner D. Ranc V. Panseri S. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:2372. doi: 10.3390/nano12142372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver C. L. LaRosa J. M. Luo X. Cui X. T. ACS Nano. 2014;8:1834–1843. doi: 10.1021/nn406223e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T. Zhou X. Xing D. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4185–4194. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynum S., Hugdahl J., Hox K., Hildrum R. and Nordvik M., Micro-domain graphitic materials and method for producing the same (Patent), PCT/NO1998/000093, 2008, vol. 18

- Lynum S., Hugdahl J., Hox K., Hildrum R. and Nordvik M., Micro-domain graphitic materials and method for producing the same (Patent), US Pat., 20030091495A1, 2003, vol. 15

- Ranjan P., Khan R., Yadav S., Sadique M. A., Murali S. and Ban M. K., Carbon Dots in Agricultural Systems, Academic Press, 2022, pp. 117–133 [Google Scholar]

- Anand David A. V. Arulmoli R. Parasuraman S. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2016;10:84–89. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.194044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudenmaier L. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1898;31:1481–1487. doi: 10.1002/cber.18980310237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zygouri P. Tsoufis T. Kouloumpis A. Patila M. Potsi G. Sevastos A. A. Sideratou Z. Katsaros F. Charalambopoulou G. Stamatis H. Rudolf P. Steriotis T. A. Gournis D. RSC Adv. 2018;8:122–131. doi: 10.1039/C7RA11045F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zygouri P. Spyrou K. Papayannis D. K. Asimakopoulos G. Dounousi E. Stamatis H. Gournis D. Rudolf P. AppliedChem. 2022;2:93–105. doi: 10.3390/appliedchem2020006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spyrou K. Potsi G. Diamanti E. K. Ke X. Serestatidou E. Verginadis I. I. Velalopoulou A. P. Evangelou A. M. Deligiannakis Y. Van Tendeloo G. Gournis D. Rudolf P. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:5841–5850. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claramunt S. Varea A. López-Díaz D. Velázquez M. M. Cornet A. Cirera A. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:10123–10129. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhouzaam A. Abdelrazeq H. Khraisheh M. AlMomani F. Hameed B. H. Hassan M. K. Al-Ghouti M. A. Selvaraj R. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:1240. doi: 10.3390/nano12081240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar Z. Ni Z. H. Wu X. Shi Z. X. Nan H. Y. Bai J. Sun L. T. Carbon. 2013;61:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.04.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. Chhowalla M. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:2392–2415. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzi M. Bruneel J.-L. Talaga D. Bokobza L. Carbon. 2016;107:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Numata Y. Tanaka H. Food Chem. 2011;126:751–755. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsagkalias I. S. Manios T. K. Achilias D. S. Polymers. 2017;9:432. doi: 10.3390/polym9090432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyrou K. Calvaresi M. Diamanti E. K. Tsoufis T. Gournis D. Rudolf P. Zerbetto F. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015;25:263–269. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201402622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski S. Sawosz E. Kutwin M. Wierzbicki M. Hinzmann M. Grodzik M. Winnicka A. Lipińska L. Włodyga K. Chwalibog A. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:1585–1596. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S77591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski S. Strojny-Cieślak B. Wierzbicki M. Kutwin M. Sawosz E. Kamaszewski M. Matuszewski A. Sosnowska M. Szczepaniak J. Daniluk K. Lange A. Pruchniewski M. Zawadzka K. Łojkowski M. Chwalibog A. Materials. 2021;14:4250. doi: 10.3390/ma14154250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru A. M. Moroșan A. Tihăuan B. Oprea O. Motelică L. Trușcă R. Nicoară A. I. Popescu R. C. Savu D. Mihăiescu D. E. Ficai A. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:1943. doi: 10.3390/nano12111943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelin M. Fusco L. Martín C. Sosa S. Frontiñán-Rubio J. González-Domínguez J. M. Durán-Prado M. Vázquez E. Prato M. Tubaro A. Nanoscale. 2018;10:11820–11830. doi: 10.1039/C8NR02933D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi E. Akhavan O. Shamsara M. Ansari Majd S. Sanati M. H. Daliri Joupari M. Farmany A. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:6201–6209. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S260228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Zhou W. Li X. Ren J. Ji G. Du J. Tian W. Liu Q. Hao A. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:200. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02359-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.