Abstract

A series of pyridine dipyrrolide actinide(IV) complexes, (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF) and An(MesPDPPh)2 (An = U, Th, where (MesPDPPh) is the doubly deprotonated form of 2,6-bis(5-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine), have been prepared. Characterization of all four complexes has been performed through a combination of solid- and solution-state methods, including elemental analysis, single crystal X-ray diffraction, and electronic absorption and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopies. Collectively, these data confirm the formation of the mono- and bis-ligated species. Time-dependent density functional theory has been performed on all four An(IV) complexes, providing insight into the nature of electronic transitions that are observed in the electronic absorption spectra of these compounds. Room temperature, solution-state luminescence of the actinide complexes is presented. Both Th(IV) derivatives exhibit strong photoluminescence; in contrast, the U(IV) species are nonemissive.

Short abstract

The synthesis and characterization of isostructural thorium(IV) and uranium(IV) adducts of a pyridine dipyrrolide ligand are reported. The thorium derivatives are photoluminescent, while the uranium complexes are nonemissive.

Introduction

A fundamental challenge in the study of molecules and materials derived from actinide ions is understanding the electronic structure of these elements.1−6 Interest in this area of research is driven, in part, by the lack of clarity in the role that 5f orbitals play in bonding and reactivity. Over the past three decades, progress has been made toward understanding the bonding and reactivity of early actinide complexes with unique ligand sets.7−9 It has been demonstrated that the 5f orbitals of the early actinides feature increasing f-orbital participation in bonding across the series (Th ≪ U < Np < Pu). This has been attributed to spin–orbit coupling that results in a decrease in the orbital energy degeneracy and an increase in the energy gaps between the 5f and 6d orbitals.10,11 Bonding descriptions of thorium compounds are unique because the 5f orbitals are slightly higher in energy than the 6d orbitals, resulting in bonding dominated by contributions from the metal 6d orbitals and π orbitals of the coordinated ligand. This is a notable difference compared to uranium, neptunium, and plutonium; as such, comparison between the electronic properties of isostructural thorium and uranium complexes presents an opportunity to probe the electronic effects of the addition of increased f-orbital participation in bonding in organoactinide species.

Historically, coordination chemistry involving uranium has focused on the uranyl moiety, [UO2]2+, due to its ubiquity in the environment and nuclear waste. Uranyl complexes have typically possessed ligands stable toward oxygen and moisture, targeting implementation in existing nuclear fuel processes.12,13 While pyrrole-derived ligands have been reported widely in studies describing the coordination chemistry of actinyl ions,14−20 actinide complexes in the 4+ oxidation state containing these ligands are comparatively scarce (Figure 1). The majority of uranium(IV) and thorium(IV) pyrrole complexes reported in the literature feature polypyrrolic macrocycles that bind uranium and thorium cations.21−23 For example, Sessler and co-workers have described a series of Th(IV), U(IV), and Np(IV) complexes featuring coordination to dipyriamethyrin.21 Additionally, Arnold and Love have demonstrated that polypyrrolic “Pacman” ligands are excellent platforms for reductively functionalizing uranyl bonds and have recently shown that these macrocycles can also stabilize UIV/UIV bent and linear μ-oxo complexes.22 Similarly, Arnold and co-workers have reported the utility of a corrole macrocycle, Mes2(p-OMePh)corrole, to coordinate Th(IV) and U(IV) cations, forming dimeric species bridged via bis(μ-chlorido) linkages.23

Figure 1.

Selected actinide(IV) complexes featuring pyrrole-derived ligands.

Of late, a new class of tridentate pincer ligands, pyridine dipyrrolides (PDPs) in the dianionic, doubly deprotonated form, have attracted attention as ligands for both transition metal and main group elements. Interest in these ligands has focused on the utility of the resultant complexes in photochemistry and catalysis.24−36 The group(IV)-derived photosensitizer Zr(MesPDPPh)2, where (MesPDPPh)2– is the doubly deprotonated form of 2,6-bis(5-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine), was recently reported by some of us.33 Thorough photophysical and theoretical studies of this compound have revealed that Zr(MesPDPPh)2 possesses a long-lived triplet excited state that exhibits photoluminescence (ΦPL = 0.45). Recent efforts in this space have focused on the isolation of heavier element congeners of the Zr(MesPDPPh)2 complex, notably Hf(IV) and Sn(IV), to investigate the effect of heavy atoms on the photophysical properties of the resultant complexes.38,78

The precedented coordination chemistry of PDP ligands with heavy group 4 metals, Zr(IV) and Hf(IV) in particular, was the basis of our interest in these ligands for the investigation of Th(IV) and U(IV) coordination chemistry. Indeed, second- and third-row group 4 metals are often considered to be nonradioactive surrogates for Th(IV) and U(IV). The goal of isolating isostructural U(MesPDPPh)2 and Th(MesPDPPh)2 compounds was identified as a means to probe what consequences the addition of f electrons may have on the electronic properties of the resulting An(MesPDPPh)2 complexes. In addition, with the exception of uranyl complexes whose photophysical properties have been studied in depth,13,37−41 photophysical studies of molecular actinide compounds are rare.

Herein, we report the synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of a series of pyridine dipyrrolide (PDP) f-element compounds. Access to the targeted bis-ligand species has been enabled through the formation of monoligated, dichloride intermediates, (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF). Theoretical studies using time-dependent density functional theory have confirmed LMCT transitions for the uranium compounds and a combination of intraligand charge transfer (ILCT) and ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) transitions for the thorium congeners. (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) and Th(MesPDPPh)2 both display strong photoluminescence with quantum yields similar to that of the Zr analogue and long lifetimes on the order of microseconds.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All air- and moisture-sensitive manipulations were carried out using a standard high-vacuum line, Schlenk techniques, or an MBraun inert atmosphere drybox containing an atmosphere of purified dinitrogen. All solids were dried under high vacuum to bring into the glovebox. Solvents for air- and moisture-sensitive manipulations were dried and deoxygenated using a glass contour solvent purification system (Pure Process Technology, LLC) and stored over activated 4 Å molecular sieves (Fisher Scientific) prior to use. Deuterated solvents for 1H NMR spectroscopy were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories and stored in the glovebox over activated 3 Å molecular sieves after three freeze–pump–thaw cycles. Chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. UCl4, ThCl4(DME)2, H2MesPDPPh, and K(CH2Ph) were synthesized following reported procedures.27,42−44

Safety Considerations

Caution! Depleted uranium (primary isotope 238U) is a weak α-emitter (4.197 MeV) with a half-life of 4.47 × 109 years, and 232Th is a weak α-emitter (4.082 MeV) with a half-life of 1.41 × 1010 years; manipulations and reactions should be carried out in monitored fume hoods or in an inert atmosphere drybox in a radiation laboratory equipped with α and β counting equipment.

Synthesis of (MesPDPPh)MCl2(THF); M = U (1a), Th (1b)

In the glovebox, H2MesPDPPh (0.015 g, 0.025 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in approximately 3 mL of THF in a 20 mL scintillation vial equipped with a stir bar. In a separate vial, LiN(SiMe3)2 (0.009 g, 0.053 mmol, 2.1 equiv) was dissolved in 3 mL of THF and added dropwise to the stirring H2MesPDPPh solution to make Li2MesPDPPh. The resultant solution was stirred for 2 h and then transferred to a 15 mL pressure vessel equipped with a stir bar. The actinide metal salt, UCl4 or ThCl4(DME)2 (0.01 g, 1 equiv), was dissolved in THF and added dropwise to the Li2MesPDPPh solution while stirring. The pressure vessel was sealed with a Teflon-lined cap, removed from the glovebox, and stirred overnight at 65 °C. The next day, the pressure vessel was cooled to room temperature and brought back into the glovebox. The resulting red (U) or yellow (Th) solution was transferred to a vial and dried under vacuum. The solid was triturated with pentane until washings ran clear and was dried under reduced pressure. The solid was dissolved in benzene and filtered over Celite and a glass frit, followed by removal of the solvent in vacuo, affording the title compound.

(MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (1a)

(0.015 g, 0.015 mmol, 62%.) 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 9.75 (s, 12H), 3.94 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H), −0.13 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 4H), −1.57 (s, 4H), −2.79 (s, 2H), −4.75 (s, 1H), −5.59 (s, 6H), −13.68 (s, 2H), −20.61 (s, 4H), −29.91 (s, 4H). Crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a toluene solution of the compound at −30 °C. Anal. Calcd for C47H45Cl2N3OU (mol. wt. 976.824 g/mol): C, 57.79%; H, 4.64%; N, 4.30%. Found: C, 57.64%; H, 4.63%; N, 3.99%.

(MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (1b)

(0.008 g, 0.008 mmol, 47%.) 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.56–7.51 (m, 4H), 7.19 (s, 6H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (s, 4H), 6.43 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (s, 2H), 2.58 (s, 12H), 2.01 (s, 4H), 1.28–1.23 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, C6D6) δ 155.74, 141.32, 140.34, 139.95, 138.75, 138.04, 137.88, 136.04, 130.71, 130.27, 128.69, 128.64, 127.00, 114.48, 113.77, 25.51, 21.66, 21.10. Crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a toluene solution of the compound at −30 °C. Anal. Calcd for C47H45Cl2N3OTh (mol. wt. 970.835 g/mol): C, 58.15%; H, 4.67%; N, 4.33%. Found: C, 58.15%; H, 4.59%; N, 4.19%.

Synthesis of M(MesPDPPh)2; M = U (2a), Th (2b)

In a 20 mL scintillation vial, (MesPDPPh)MCl2(THF) (U: 0.05 g, 0.051 mmol; Th: 0.028 g, 0.029 mmol) was dissolved in a minimal amount of THF. In a separate vial, K(CH2Ph) (2.1 equiv) was dissolved in THF, and both vials were frozen completely in the glovebox coldwell at −80 °C. Upon thawing, the (MesPDPPh)MCl2(THF) solution was added to the second vial, inducing a color change to dark burgundy (U) or dark red (Th). The vial was immediately dried under vacuum. The solid was suspended in diethyl ether and filtered over a glass frit with Celite. The resultant solution was pumped dry to afford the intermediate compound (MesPDPPh)M(CH2Ph)2(THF) (U: 0.028 g, 0.026 mmol; Th: 0.024 g, 0.022 mmol). This intermediate complex was dissolved in toluene and transferred to a 15 mL pressure vessel equipped with a stir bar. H2MesPDPPh (U: 0.014 g, 0.023 mmol; Th: 0.013 g, 0.022 mmol) was suspended in toluene and added to the pressure vessel, followed by sealing the vessel with a Teflon-lined cap. The pressure vessel was brought out of the glovebox, set to stir, and heated to 120 °C for 2 days. Then the dark-red (U) or bright-orange (Th) solution was allowed to cool to room temperature before being brought back into the glovebox. The resulting product was filtered over a glass frit packed with Celite and dried in vacuo. The solid was triturated with pentane until washings ran clear and was dried again to afford the title compound.

U(MesPDPPh)2 (2a)

(0.025 g, 0.017 mmol, 69%.) 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 18.47 (s, 4H), 12.28 (s, 24H), 6.21 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 8H), 6.07–5.98 (m, 12H), 2.89 (s, 8H), −2.87 (s, 12H), −3.44 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), −8.42 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H). Crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were grown from a concentrated diethyl ether solution of the compound at −30 °C. Anal. Calcd for C86H74N6U (mol. wt. 1429.65 g/mol): C, 71.25%; H, 5.22%; N, 5.88%. Found: C, 71.37%; H, 5.22%; N, 5.53%.

Th(MesPDPPh)2 (2b)

(0.023 g, 0.023 mmol, 77%.) 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.70 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 8H), 7.35 (q, J = 7.7 Hz, 8H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 8H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 6.54 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 11H), 6.05 (s, 4H), 2.16 (s, 24H), 1.94 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, C6D6) δ 154.85, 141.59, 139.14, 138.77, 136.93, 135.97, 130.98, 130.35, 130.20, 128.73, 126.99, 116.62, 113.45, 22.25, 21.09, 20.50. Crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction were grown from a concentrated diethyl ether solution of the compound at −30 °C. Anal. Calcd for C86H74N6Th (mol. wt. 1423.66 g/mol): C, 71.08%; H, 5.25%; N, 5.72%. Found: C, 71.06%; H, 5.11%; N, 5.33%.

Physical Measurements

1H NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature on a 400 MHz Bruker AVANCE spectrometer or a 500 MHz Bruker AVANCE spectrometer locked on the signal of deuterated solvents. All of the chemical shifts are reported relative to the chosen deuterated solvent as a standard. Electronic absorption measurements were recorded at room temperature in anhydrous toluene in sealed 1 cm quartz cuvettes using an Agilent Cary 6000i UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer. Emission spectra were collected with a Spex Fluoromax-3 fluorometer (Horiba) with a photomultiplier tube detector. Sample absorbances were kept below 0.2 OD in anhydrous toluene in 1 cm quartz cuvettes. Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) measurements were acquired using a home-built optical setup. Samples in anhydrous toluene solution were placed in 1 cm quartz cuvettes and photoexcited by a defocused laser beam provided by a pulsed laser diode (PicoHarp 300, PDL 800-D). Data was collected on a Tektronix TBS 1102B-Edu digital oscilloscope. Elemental analysis data were obtained from the Elemental Analysis Facility at the University of Rochester. Microanalysis samples were weighed with a PerkinElmer model AD6000 autobalance, and their compositions were determined with a PerkinElmer 2400 series II analyzer. Air-sensitive samples were handled in a VAC Atmospheres glovebox.

X-ray Crystallography

Each single crystal was collected on a nylon loop and mounted on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S Dualflex diffractometer equipped with a HyPix-6000HE HPC area detector for data collection at 100.00(10) K. A preliminary set of cell constants and an orientation matrix were calculated from a small sampling of reflections.45 A short pre-experiment was run, from which an optimal data collection strategy was determined. The full data collection for all four complexes was carried out using a PhotonJet (Cu) X-ray source. After the intensity data were corrected for absorption, the final cell constants were calculated from the xyz centroids of the strong reflections from the actual data collections after integration.45 The structure was solved using SHELXT46 and refined using SHELXL.47 Most or all non-hydrogen atoms were assigned from the solution. Full-matrix least-squares/difference Fourier cycles were performed, which located any remaining non-hydrogen atoms. All of the non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. All of the hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotropic displacement parameters. Structures 1a and 1b are isomorphous; structures 2a and 2b are as well.

For complexes 1a and 1b, the asymmetric unit contains one metal complex in a general position and one-half each of three toluene solvent molecules in special positions. Toluene molecules C48-C51 and C52-C55 are modeled as disordered over crystallographic 2-fold axes (0.50:0.50), and toluene molecule C56-C62 is modeled as disordered over a crystallographic inversion center (0.50:0.50). For complexes 2a and 2b, the asymmetric unit contains two metal complexes in general positions and one-half of a diethyl ether solvent molecule on a crystallographic inversion center; the ether molecule is modeled as disordered over the inversion center (0.50:0.50).

Computational Methods

All calculations were performed using the ORCA quantum chemical program package, version 5.0.1.48,49 Geometry optimizations used the PBE functional50 and were accelerated using the resolution of identity (RI) approximation.51,52 Scalar-relativistic effects were included via the zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA)53 using the relativistically recontracted triple-ζ quality basis set ZORA-def2-TZVP54 on nitrogen, oxygen, and chlorine atoms and SARC-ZORA-TZVP55 on thorium and uranium. All other atoms were handled with the recontracted split-valence ZORA-def2-SVP basis set.54 Noncovalent interactions were considered via atom-pairwise dispersion corrections with Becke–Johnson (D3BJ) damping.56,57 The TD-DFT calculations used the B3LYP density functional58 and were accelerated using the RIJCOSX approximation.59,60 Relativistic effects were included using the Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH) Hamiltonian with DKH-specific basis sets analogous to those used in the geometry optimizations (SARC-DKH-TZVP, DKH-def2-TZVP, and DKH-def2-SVP). The Tamm–Dancoff approximation was not used, and the effects of spin–orbit coupling (SOC) were probed using a spin–orbit mean field (SOMF) approach.61 All solvation effects were handled using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (C-PCM) and a Gaussian charge scheme.62 All orbital and spin-density plots were generated using the program Gabedit.63

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) Complexes

Initial attempts to synthesize AnIV(MesPDPPh)2 (An = Th, U) complexes focused on the uranium(IV) derivative. Two equivalents of LiN(SiMe3)2 were added to a solution of H2MesPDPPh in THF, affording the in situ generation of Li2MesPDPPh. Addition of this solution to 0.5 equiv of UCl4 in THF resulted in a gradual color change to dark red; after stirring the reaction mixture overnight, volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture by 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed the formation of a major product featuring 11 paramagnetically shifted and broadened resonances (Figure S1), with a general pattern resembling that of the monoligated uranium(IV) siloxide complex, (MesPDPPh)U(OSiMe3)2(DMAP) (where DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine), reported previously by our group.64 Free ligand was also observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product. Collectively, these results suggest that only a single PDP ligand is added to the uranium center under the described reaction conditions.

Further support for addition of a single ligand to the uranium center was obtained through targeted synthesis of the monoligated complex, (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF). The addition of 1 equiv of Li2MesPDPPh to a solution of UCl4 in THF results in a gradual color change to dark red after heating to 70 °C for 16 h. Workup of the product afforded (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (1a) in 60% yield (Scheme 1; see Experimental Section for additional details). The formation of the monoligated uranium species was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy; 11 paramagnetically shifted and broadened resonances ranging from +10 to −30 ppm were observed (Figure S2), matching the result obtained in the aforementioned attempt to access UIV(MesPDPPh)2. The distribution of resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum is consistent with the formation of a product with C2v symmetry. Closer inspection of the integrations in the 1H NMR spectrum of (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) reveals a resonance at −4.75 ppm with a relative integration of one and is assigned to the 4-pyridyl proton. This particular signal is typically used as a spectroscopic benchmark for PDP ligands bound to transition metal and metalloid centers.24,65 Moreover, a diagnostic singlet is observed at −2.79 ppm and is attributed to the 4-pyrrolide hydrogens. The highest-intensity signal in the spectrum is located at 9.75 ppm, with a relative integration of 12. We assign this resonance to the ortho-methyl groups of the mesityl substituent of the PDP ligand. A signal located at −5.59 ppm with a relative integration of six is assigned to the corresponding para-methyl group protons of the mesityl functionality.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF) Complexes (An = U (1a); Th (1b)).

Crystals of 1a suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) were grown from the slow diffusion of pentane into a concentrated solution of the product in toluene at −30 °C. Refinement of the data confirmed the structural composition of 1a as the anticipated six-coordinate species (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (Figure 2, Table 1). Complex 1a displays a distorted octahedral geometry at the uranium center; the equatorial positions of the octahedron are defined by the meridionally coordinated N3-(MesPDPPh) chelate and the tetrahydrofuran ligand. Two chloride ligands occupy the axial sites, and the pincer ligand enforces a N1–U–N3 bite angle of 132.67(16)° for 1a. This structural feature represents the largest deviation from octahedral geometry in 1a. The U–Npyridine distance of 2.474(2) Å is significantly shortened in comparison to that of (MesPDPPh)U(OSiMe3)2(DMAP) (U–Npyridine = 2.545(3) Å).64 Truncation of the U–Npyrrolide distances (U–N1, U–N3) of 1a (U–Npyrrolide = 2.309(5), 2.301(5) Å) is also observed in comparison to (MesPDPPh)U(OSiMe3)2(DMAP) (U–Npyrrolide = 2.545(3) Å). The U–Npyrrolide distances are among the shortest reported for U(IV)-pyrrolide species (U(IV)–Npyrrolide = 2.389(3)–2.531(7) Å).66−68 Collectively, these results suggest that the uranium(IV) center binds more tightly to the (MesPDPPh)2– ligand upon substitution of the electron-donating siloxide moieties with chlorido ligands. The U–Cl bond distances in 1a (2.5844(13) and 2.5927(14) Å) are slightly shorter than values reported previously for U(IV)Cl2(L) (L = neutral ligand) complexes (2.614(2)–2.751(3) Å).21,69−71 We hypothesize that the trans positioning of the chloride substituents renders the inverse trans influence operative in these axially bound X-type ligands.72

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (1a) shown with 30% probability ellipsoids. The molecular structure of (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (1b) is similar to that of 1a; the corresponding image can be found in the Supporting Information (Figure S4). Hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules have been removed for clarity. Key: pink, U; blue, N; gray, C; light green, Cl; red, O.

Table 1. Pertinent Bond Distances and Angles for Complexes (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF) (An = U, 1a; Th, 1b), with Distances and Angles for (MesPDPPh)U(OSiMe3)2(DMAP)64 Included for Comparison.

| Complex | (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (1a) An = U, E = Cl | (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (1b) An = Th, E = Cl | (MesPDPPh)U(OSiMe3)2(DMAP) An = U, E = OSiMe3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| An–E | 2.5844(13), 2.5927(14) Å | 2.6528(10), 2.6566(11) Å | 2.114(2), 2.123(2) Å |

| E–An–E | 174.04(4)° | 172.33(3)° | 178.95(8)° |

| An–Npyr | 2.474(4) Å | 2.548(3) Å | 2.545(3) Å |

| An–Npyrrolide | 2.301(5), 2.309(5) Å | 2.362(3), 2.358(4) Å | 2.369(3), 2.371(3) Å |

With complex 1a in hand, we next targeted the preparation of the isostructural thorium analogue, (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (1b). The synthesis of 1b is motivated by our interest in comparing the electronic structure of actinide complexes with and without 5f electrons (U(IV) = 5f2 vs Th(IV) = 5f0). The addition of in situ-generated Li2MesPDPPh in THF to a solution of ThCl4(DME)2 in the same solvent resulted in a gradual color change to yellow after heating to 70 °C for 16 h. Workup of the solution afforded complex 1b in 46% yield (Scheme 1). Characterization of the purified product by 1H NMR spectroscopy reveals the expected number of resonances (11) with relative integrations for a C2v-symmetric product in solution (Figure S3). Characteristic signals measured in the 1H NMR spectrum of 1b include a triplet at 6.43 ppm assigned to the 4-pyridyl proton. A diagnostic singlet is also observed at 6.14 ppm, corresponding to the 4-pyrrolide hydrogens. The ortho- and para-methyl groups of the mesityl moiety on the PDP ligand are located at 2.58 and 2.10 ppm, respectively, with relative integrations of 12:6. Resonances assigned to a bound THF ligand were identified at 3.37 (α-CH2) and 1.10 (β-CH2) ppm for 1b, with integrations consistent with a 1:1 THF:(MesPDPPh) ligand ratio. 13C NMR of 1b was also obtained and is consistent with the anticipated spectrum of the product (Figure S5).

Yellow crystals of (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) suitable for analysis via SCXRD were obtained from the slow diffusion of pentane into a concentrated toluene solution of 1b. Refinement of the data confirmed the identity of complex 1b as the pseudo-octahedral, six-coordinate species (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (Figure 2, Table 1). Notably, complexes 1a and 1b both crystallize in the Pbcn space group and with nearly identical unit cells. As observed in 1a, the (MesPDPPh)2– ligand and a bound tetrahydrofuran molecule occupy the equatorial plane of 1b, with two chloride atoms observed in the axial positions in a trans configuration. The Th–Npyrrolide distances of 2.362(3) and 2.358(4) Å are significantly shorter than values reported for a similar thorium(IV) bischloride complex bound to the tripyrrolide dianionic ligand, [(2,5-[(C4H3N)CPh2]2[C4H2N(Me))]ThCl2(thf) (Th–Npyrrolide = 2.408(7) and 2.399(7) Å).73 This feature of the molecular structure is reminiscent of complex 1a, which also displays truncated An–Npyrrolide bonds. The Th–Cl bond lengths in (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (2.6528(10), 2.6566(11) Å) are similar to values reported for [(C4H3N)CPh2]2[C4H2N(Me)]ThCl2(THF) (2.651(2), 2.681(2) Å) and also fall in a similar range as bound chloride atoms in a thorium complex with a 4,5-bis(2,6-diisopropylanilino)-2,7-di-tert-butyl-9,9-dimethylxanthene ligand (Th–Namido = 2.698(3), 2.686(3) Å).3

The striking differences in color between the uranium (dark red) and thorium (bright yellow) derivatives of (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF) prompted further characterization by electronic absorption spectroscopy. To our surprise, the electronic absorption spectra of 1a and 1b in toluene are quite similar (Figure 3). The UV region of each spectrum is dominated by two absorption features that are reminiscent of the absorption maxima of the free ligand, H2MesPDPPh (364 and 316 nm in THF), and therefore were assigned to originate predominantly from π–π* transitions within the individual ligands. Notably, these absorption bands are slightly shifted from those of the protonated PDP ligand, consistent with successful metalation (Figure S6); for an in-depth discussion of the absorption profile of the ligand, we direct readers to a recent report from Milsmann and co-workers.74 In the electronic absorption spectrum of 1b, these two intense bands are observed at 318 nm (ε = 14,006 M–1 cm–1–) and 360 nm (ε = 12,215 M–1 cm–1). In addition, complex 1b also contains a lower-energy transition at 458 nm (ε = 6,203 M–1 cm–1–), distinct from the electronic absorbance spectrum of H2MesPDPPh. A more detailed analysis of this low-energy feature is provided in the computational section below.

Figure 3.

Electronic absorption spectra for (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) (1a) and (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) (1b) collected at room temperature in toluene. The inset shows the near-infrared region of the electronic absorption spectrum of 1a to highlight f–f transitions of the U(IV) center.

In the case of the uranium complex, the electronic absorbance spectrum of 1a features two intense bands at 316 nm (ε = 20,273 M–1 cm–1–) and 356 nm (ε = 16,650 M–1 cm–1–). Similar to 1b, complex 1a also contains a lower-energy feature at 462 nm (ε = 6,391 M–1 cm–1). However, the band shape of this absorption event is quite different than that observed in the case of 1b. A significant increase in bandwidth results in an extension of absorption to ∼600 nm, translating to the dark-red color observed visually for complex 1a. This unique feature is reminiscent of a ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) transition measured experimentally and confirmed by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) in (MesPDPPh)UO2(THF).65 An analysis of the near-infrared region of the electronic absorbance spectrum of 1a also revealed weak and sharp f–f transitions, consistent with the assignment of a +4 oxidation state (5f2 valence electron configuration) of uranium.

To gain insight into the origin of the observed electronic transitions in the electronic absorption spectra of 1a and 1b, density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations were performed on (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) and (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF). Full molecule geometry optimizations were performed at the PBE/D3BJ level of theory. Relativistic effects due to the actinide ions were included through use of the zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA) with the appropriate relativistically recontracted basis sets. The resulting structural parameters for 1a and 1b are in good agreement with the experimental data. Single-point calculations at the B3LYP level of theory using the Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH) formalism to include relativistic effects were then performed to obtain insights into the molecular orbital manifolds of 1a and 1b.

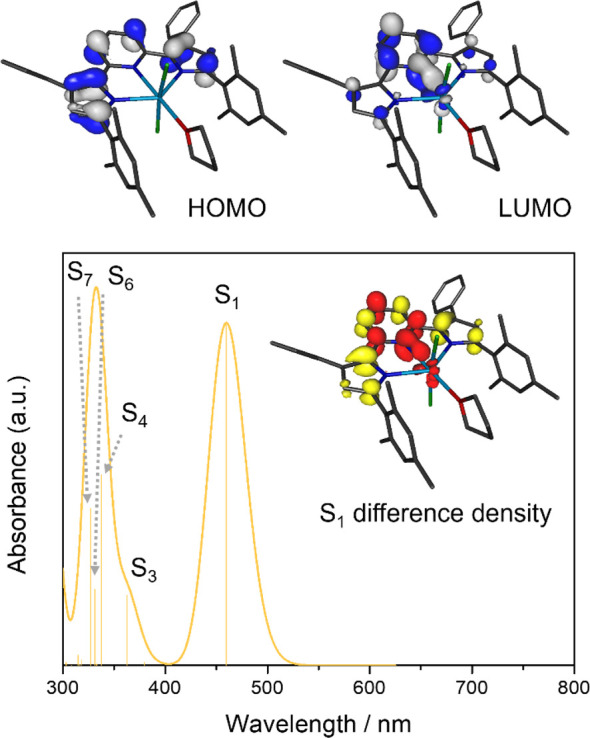

Based on the experimentally observed diamagnetism of thorium derivative 1b, a singlet ground state was assumed for all calculations and provided an electronic structure consistent with a +IV oxidation state for the thorium center with seven unoccupied f orbitals. Consistent with largely ionic metal–ligand interactions, the filled frontier molecular orbitals show negligible contributions from the thorium ion with less than 5% thorium character in the HOMO to HOMO–17. The HOMO of 1b is exclusively ligand-centered with major contributions from the π-systems of the electron-rich pyrrolide heterocycles, resembling the HOMOs of the ligand precursor, H2MesPDPPh, and its lithium salt, Li2MesPDPPh.75 Similarly, the LUMO and LUMO+1 are predominantly ligand-centered with major contributions from the pyridine π system and only minor contributions from thorium 6d orbitals (LUMO: 11% Th character, LUMO+1: 8% Th character). Like the HOMO, the LUMO of 1b resembles those of H2MesPDPPh and Li2MesPDPPh, providing a first indication that the lowest-energy excited state in 1b should have intraligand character (IL).

To further support our electronic structure analysis, TD-DFT calculations were performed at the B3LYP/DKH level of theory. The computed electronic absorption spectrum is in good agreement with the experimental data and exhibits a lowest-energy absorption band at 460 nm (Figure 4). Further analysis of the computational data revealed that this spectral feature can be attributed to a transition to the S1 excited state that is best described as the result of a dipole-allowed single-electron excitation from the HOMO to the LUMO of 1b. The dominating intraligand character of the S1 state (1IL), implied by the molecular orbital composition of the HOMO and LUMO, is further supported by Mulliken population analysis for the S1 state that reveals only minor charge migration from the ligand to the metal (ΔqTh = −0.12 e; Figure 4) compared to the ground state. Four additional transitions with appreciable intensities contribute to the second absorption feature predicted in the UV region between 300 and 400 nm. These are assigned as transitions to the S3, S4, S6, and S7 states and are all predominantly 1IL in nature. The absence of any low-energy ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) transitions is consistent with the very negative reduction potential for Th(IV) that indicates that occupation of the metal f and d orbitals is unfavorable for thorium.75

Figure 4.

Top: HOMO and LUMO of (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) obtained by DFT calculations. Bottom: TD-DFT calculated absorption spectrum (fwhm = 2000 cm–1) with individual transitions indicated by the stick plot. The inset shows the difference density for the lowest-energy excited state (red = increased electron density, yellow = reduced electron density), highlighting its 1IL character.

A more complex electronic structure analysis, using the unrestricted Kohn–Sham (UKS) formalism, is required for the paramagnetic uranium complex, 1a. Considering the experimentally assigned U(IV) oxidation state (5f2) of the complex, a triplet ground state was assumed for all calculations, and the computational results for 1a are consistent with a +IV oxidation state of the central actinide ion (Figure 5). As expected for a 5f2 configuration, two electrons are located in α-spin orbitals with majority contributions from uranium 5f orbitals (HOMO–3(α) 74% and HOMO–2(α) 58% U character), while all uranium 5f orbitals are unoccupied for the β-spin manifold. Mulliken population analysis provides a spin density value of 2.16 for uranium, also consistent with a 5f2 configuration and a triplet ground state. For both the α and β sets of orbitals of 1a, the HOMO and HOMO–1 are almost identical to those of thorium analog 1b and are exclusively ligand-centered (0% U character, major contributions from the PDP π system). In contrast, the LUMO(α) is best described as a uranium 5f orbital (79% U contribution), while the LUMO(β) shows more limited yet still substantial metal 5f character (39%). Therefore, low-energy transitions with significant LMCT character can be expected for 1a in contrast to 1b, consistent with the more moderate potentials for the UIV/UIII redox couple.75

Figure 5.

Top: Selected frontier molecular orbitals of (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) obtained by DFT calculations. The HOMO–2(α) and HOMO–3(α) have no corresponding occupied analogs in the β-spin orbital manifold and represent the magnetic orbitals (SOMOs) of the complex. Bottom: Spin density obtained by Mulliken population analysis for (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF).

The paramagnetic nature and the presence of low-energy f–f excited states also complicate the computational analysis of the electronic transitions for 1a compared to 1b. An accurate prediction of such metal-centered transitions and any potential charge transfer transitions involving the metal center would require the use of high-level multireference ab initio methods with large active spaces and is beyond the scope of this study. Instead, TD-DFT calculations were utilized to probe the presence of low-energy charge transfer states. While this approach cannot be expected to yield quantitatively accurate energies for the resulting electronic transitions or an accurate reproduction of the experimental electronic absorption spectrum overall, it nevertheless provides qualitative insight into the accessibility of charge transfer states in 1a in comparison to 1b.

Within the first 70 TD-DFT excitations, the lowest-energy transition excluding f–f excited states was identified as an absorption band at 634 nm. The corresponding excited state has significant 3LMCT character as reflected in the significant charge migration from the PDP ligand to the uranium center (ΔqU = −0.74 e). This charge distribution can be understood by an inspection of the unrelaxed difference density for this transition (Figure 6); a significant loss of electron density for the pyrrolide rings and an increase in electron density at the uranium ion are observed. Further supporting LMCT character, the spin density at the metal center increases to 2.83, in line with an f3 configuration and three unpaired electrons for uranium in this excited state. A second, more intense absorption feature centered at 494 nm can also be attributed to a single excited state with significant 3LMCT character (ΔqU = −0.32 e). The most intense absorption feature within the first 70 TD-DFT states was observed at 399 nm and is a combination of several energetically close-lying excited states that are predominantly IL in character (ΔqU < −0.1 e). These results demonstrate that several LMCT and IL transitions are accessible at low energies for 1a, which may explain the broad absorption band for this complex observed experimentally.

Figure 6.

TD-DFT calculated absorption spectrum (fwhm = 2000 cm–1) including the first 70 transitions for (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) with individual transitions indicated by the stick plot. The insets show the difference densities for the two lowest-energy charge transfer excited states (red = increased electron density, yellow = reduced electron density), highlighting their 1LMCT character.

Synthesis and Characterization of AnIV(MesPDPPh)2 Complexes

Returning to our initial aim to isolate An(MesPDPPh)2 compounds, new synthetic protocols were developed starting from complexes 1a and 1b. No reaction is observed when 1 equiv of in situ-generated Li2MesPDPPh in THF is added to complex 1a, even under prolonged reaction periods at elevated temperatures. This is likely a result of the bulky nature of the (MesPDPPh)2– ligand. To probe this hypothesis, we attempted the synthesis of the analogous bis-ligand complexes, featuring the much less bulky pyridine dipyrrolide ligands, (PhPDPPh)2–. These compounds can be synthesized at room temperature directly from the salt metathesis reaction of 2 equiv of in situ-prepared Li2PhPDPPh and 1 equiv of AnCl4 (An = UCl4 or ThCl4(DME)2) in Et2O or toluene. (See Figures S7 and S8 for the characterization of these complexes by 1H NMR and Table S2 for crystallographic details.)

Given the challenges noted in the attempted salt metathesis reactions for the coordination of a second pincer ligand, we proposed instead to alkylate the monoligated uranium(IV) compound, hypothesizing that the resultant uranium–carbon bonds would serve as an internal base to drive the formation of U(MesPDPPh)2. Indeed, evidence supporting the need to access an organometallic intermediary complex to isolate bis-PDP compounds was shown in a recent work by some of us; a cyclometalated Zr compound, (cyclo-MesPDPPh)ZrBn, was crucial to facilitate bis-ligand complex formation.76 The addition of 2 equiv of benzyl potassium (KCH2Ph) to (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) in THF at −80 °C resulted in an immediate color change from red to burgundy. Following a brief workup (see Experimental Section for details), the likely product of alkylation was resuspended in toluene and a second equivalent of H2MesPDPPh was added; subsequently, a gradual color change to bright red-orange was observed. After heating at 120 °C for 32 h, purification of the crude reaction mixture afforded complex U(MesPDPPh)2 (2a) in good yield (69%; Scheme 2, see Experimental Section for additional details).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of An(MesPDPPh)2 (An = U, 2a; Th, 2b).

The formation of a new uranium-containing product was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Nine paramagnetically shifted and broadened resonances ranging from +19 to −9 ppm were observed, consistent with the formation of the anticipated D2d-symmetric product (Figure S9). The 1H NMR spectrum of 2a possesses a triplet resonance that integrated to 2, assigned to the 4-pyridyl protons of the PDP ligand at −3.35 ppm. A diagnostic singlet resonance attributed to the 4-pyrrolide hydrogens was present at 18.38 ppm, and a doublet appearing at −8.31 ppm represents the 3-pyridyl hydrogens. The highest-intensity peak in the spectrum is observed at 12.17 ppm, with the relative integration of 24 corresponding to the ortho-methyl protons of the mesityl group. A signal corresponding to the para-methyl protons of the PDP mesityl group is located at −2.83 ppm. Both resonances are shifted downfield in comparison to the 1H NMR spectrum of 1a, indicating that the protons are significantly deshielded upon coordination of the second ligand equivalent to the paramagnetic actinide center.

Single crystals of 2a suitable for single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) were grown from a concentrated solution of the compound in neat diethyl ether at −30 °C. Refinement of the data confirmed formation of the anticipated six-coordinate, bis-ligand complex 2a (Figure 7, Table 2). The coordination environment around uranium is best described as distorted octahedral with two meridionally bound N3-(MesPDPPh)2– ligands. The dative interaction between the U–Npyridine (Npyridine = N2, N5) moieties results in bond lengths of 2.408(4) and 2.404(4) Å, further shortened in comparison to monoligated complex 1a (U–Npyridine = 2.474(4) Å). The U–Npyrrolide (Npyrrolide = N1, N3, N4, N6) bond distances (2.338(4) Å (average of N1 and N3), 2.313(4) Å (average of N4 and N6)) are elongated from the analogous bonds in 1a (2.309(5) Å, 2.301(5) Å). This is likely a result of the steric congestion surrounding the uranium metal center upon coordination of two (MesPDPPh)2– ligands. The Npyrrolide–M–Npyrrolide bond angles for the pyridine dipyrrolide ligands in 2a are 137.25(13) and 136.71(13)°; these values are slightly decreased from those reported for Zr(MesPDPPh)2 (Npyrrolide–Zr–Npyrrolide = 143.54(8)°).33 We hypothesize that this is due to the large ionic radius of U(IV) (0.89 Å) in comparison to that of Zr(IV) (0.72 Å), which displaces the metal center from the optimal coordination pocket of the tridentate ligand.77 Consequently, a striking difference that results from this is the decrease in linearity of the N2–M–N5 bond angle in 2a (N2–U–N5 = 173.31(12)°) as compared to Zr(MesPDPPh)2 (N2–Zr–N5 = 179.42(8)°).

Figure 7.

Molecular structure of U(MesPDPPh)2 (2a) shown with 30% probability ellipsoids. The molecular structure of Th(MesPDPPh)2 (2b) is analogous to 2a; the corresponding image can be found in the Supporting Information (Figure S11). Hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules have been removed for clarity. Key: pink, U; blue, N; gray, C.

Table 2. Pertinent Bond Distances and Angles for Complexes An(MesPDPPh)2 (An = U, 2a; Th, 2b); Distances and Angles for Zr(MesPDPPh)2REF Included for Comparison.

| Complex | U(MesPDPPh)2 (2a) | Th(MesPDPPh)2 (2b) | Zr(MesPDPPh)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| M–Npyridine | 2.408(4) Å | 2.489(5) Å | 2.262(2) Å |

| 2.404(4) Å | 2.496(5) Å | 2.262(2) Å | |

| M–Npyrrolide | 2.328(4), 2.347(4) Å | 2.381(4), 2.409(4) Å | 2.170(2), 2.166(2) Å |

| 2.297(4), 2.329(3) Å | 2.348(4), 2.384(4) Å | 2.170(2), 2.165(2) Å | |

| N2–M–N5 | 173.31(12)° | 171.79(14)° | 179.42(8)° |

With complex 2a isolated, we targeted the preparation of the isostructural thorium analogue, Th(MesPDPPh)2 (2b), following a procedure similar to that invoked in the successful formation of the uranium derivative. The addition of 2 equiv of KCH2Ph to (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) in THF at −80 °C resulted in an immediate color change from yellow to bright red. Upon workup, the benzyl-substituted complex MesPDPPhTh(CH2Ph)2(THF) was redissolved in toluene and 1 equiv of H2MesPDPPh suspended in toluene was added, resulting in a color change to orange. After heating to 120 °C for 32 h, workup of the solution afforded 2b in good yield (77%; Scheme 2). Characterization of the product by 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed the expected number of resonances with relative integrations for a D2d-symmetric product in solution (Figure S10). Diagnostic signals observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of 2b include an apparent triplet resonance at 6.53 ppm that overlaps with an aryl-proton peak, assigned to the 4-pyridyl protons of the PDP ligand backbone. A singlet resonance corresponding to the 4-pyrrolide hydrogen atoms appears at 6.04 ppm, whereas the ortho-mesityl and para-mesityl methyl protons are observed as singlet resonances located upfield at 2.15 and 1.94 ppm, respectively. 13C NMR of 2b was also obtained and is consistent with the anticipated spectrum of the product (Figure S12).

Yellow crystals of 2b suitable for analysis via SCXRD were obtained from a concentrated diethyl ether solution of the compound at −30 °C. Refinement of the data confirmed the identity of complex 2b as the desired pseudo-octahedral, six-coordinate species Th(MesPDPPh)2 (Figure 7, Table 2). The bis-ligated thorium complex displays average Th–Npyrrolide bond lengths of 2.395(4) and 2.366(4) Å, similar to other reported Th–Npyrrolide bond distances.73 The Npyrrolide–M–Npyrrolide bond angles for the pincer ligands in 2b are 133.75(15) and 132.32(15)°, slightly decreased from those in 2a and Zr(MesPDPPh)2 due to the increased size of the thorium ion (Th(IV) = 0.94 Å). Bond lengths for Th–Npyridine in Th(MesPDPPh)2 are significantly shortened at 2.489(5) and 2.496(5) Å compared to a Th(IV) porphyrin complex that reports a Th–Npyridine bond length of 2.614 Å;21 this is consistent with the overall truncation in An–N bond distances that is observed in this series of An–PDP complexes.

Analysis of the optical properties of the bis-ligated complexes, 2a and 2b, was performed by electronic absorption spectroscopy (Figure 8). Complexes 2a and 2b exhibit spectra similar to those of the monoligated derivatives. The absorption profile of Th(MesPDPPh)2 displays two intense bands located at 316 nm (ε = 61,077 M–1 cm–1) and 360 nm (ε = 51,105 M–1 cm–1) as well as a lower-energy feature at 462 nm (ε = 25,397 M–1 cm–1). In comparison to complex 1b, 2b possesses higher molar extinction coefficients for all three transitions observed in the electronic absorption spectrum. This is consistent with the addition of a second equivalent of ligand to the thorium center, as all transitions are proposed to be ligand-based. The electronic absorption spectrum of 2a likewise features two intense bands at 320 nm (ε = 43,317 M–1 cm–1–) and 358 nm (ε = 36,466 M–1 cm–1–), along with a weaker absorption noted at 450 nm (ε = 16,839 M–1 cm–1). As observed in the case of 1a, this absorption feature extends far into the visible region of the spectrum. Analysis of the near-infrared region of the spectrum of 2a also reveals weak and sharp f–f transitions, consistent with the retention of a +IV oxidation state of uranium upon addition of the second PDP ligand to the metal center. Complex 2a also shows higher molar extinction coefficients in comparison to 1a; overall, the coordination of a second (MesPDPPh)2– ligand to both actinide centers increases the probability of the allowed transitions to occur in the electronic absorption spectra of these compounds.

Figure 8.

Electronic absorption spectra for U(MesPDPPh)2 (2a) and Th(MesPDPPh)2 (2b) collected at room temperature in toluene. The inset shows the near-infrared region of the electronic absorption spectrum of 2a to highlight f–f transitions of the U(IV) center.

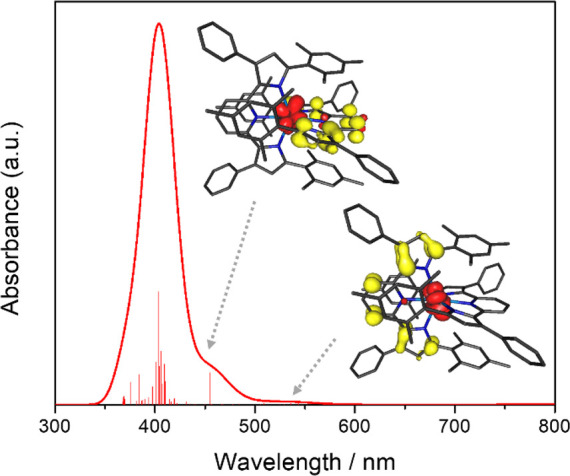

Computational analysis of the electronic structures and electronic transitions of U(MesPDPPh)2 and Th(MesPDPPh)2 was performed using the same computational approaches as described for monoligand complexes 1a and 1b. Like that noted in the case of the analysis of complex 1b, electronic structure analysis for diamagnetic thorium complex 2b proved to be straightforward and confirmed the presence of a Th(IV) center (Figure 9). All filled frontier molecular orbitals are exclusively ligand-centered with negligible contributions from the metal ion (<3%). The HOMO and HOMO–1 are nearly degenerate and exhibit major contributions from the pyrrolide π systems. Similar to the structurally related group 4 complexes Zr(MesPDPPh)2 and Hf(MesPDPPh)2, the LUMO and LUMO+1 form a degenerate orbital set (e) under idealized D2d symmetry. In contrast to its transition metal congeners, however, the LUMO/LUMO+1 of 2b exhibit only minor contributions from the Th center (10%) and contain dominant contributions from the pyridine rings of the two PDP ligands more akin to the main group compounds E(MePDPPh)2 (E = Si, Ge, Sn).

Figure 9.

Top: Depictions of the degenerate sets of HOMO/HOMO–1 and LUMO/LUMO+1 of Th(MesPDPPh)2 obtained by DFT calculations. Bottom: TD-DFT calculated absorption spectrum (fwhm = 2000 cm–1) with individual transitions indicated by the stick plot. The insets show the difference densities for the lowest-energy excited states (red = increased electron density, yellow = reduced electron density). The calculated S2 and S4 states are degenerate with respect to S1 and S3, respectively, and the corresponding difference densities can be obtained by a C2 operation interconverting the two MesPDPPh ligands.

TD-DFT calculations for 2b at the B3LYP/DKH level of theory predict a lowest-energy absorption band at 451 nm that is composed of two sets of degenerate transitions from the HOMO (a2) to the LUMO/LUMO+1 (e, S1 and S2) and from the HOMO–1 (b2) to the LUMO/LUMO+1 (S3 and S4) (Figure 9). Mulliken population analysis for the ground-state and the corresponding excited-state electron densities revealed only minor charge migration to the Th center (Δq1,2 = −0.08 e; Δq3,4 = −0.10 e), corroborating the intraligand (1IL) and singlet ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (1LLCT) character of the excited states. This is consistent with the orbital compositions of the donor and acceptor orbitals established for the ground-state electronic structure. A second absorption band computed at 350 nm can also be attributed to several higher-energy 1IL and 1LLCT transitions with minimal charge migration to the metal (Δq < −0.12 e).

Calculations for uranium analog 2a assuming a paramagnetic triplet ground state support a +IV oxidation state with an f2 electron configuration for the metal center, reflected in a spin density of 2.09 obtained by Mulliken population analysis. The HOMO and HOMO–1 for both the α- and β-orbital manifolds are degenerate under idealized D2d symmetry and exhibit exclusively ligand character much like the equivalent HOMO/HOMO–1 set for 2b. While the degenerate LUMO and LUMO+1 for the β-manifold exhibits only minor contributions from the uranium center, the corresponding orbitals in the α-set show substantial f-orbital contributions with 89.7 and 81.1% metal character. Consistent with these assignments, TD-DFT calculations predict several low-energy 3LMCT transitions between 550 and 350 nm, resulting in significant charge and spin density migration to the uranium center (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

TD-DFT calculated absorption spectrum for U(MesPDPPh)2 (fwhm = 2000 cm–1) including only the first 50 roots with individual transitions indicated by the stick plot. The insets show the difference densities for the two lowest-energy charge transfer excited states (red = increased electron density, yellow = reduced electron density), highlighting their 1LMCT character.

Luminescence Studies

We next conducted a preliminary investigation of the photophysical properties of our isostructural PDP An(IV) compounds. As described at the outset of this report, considering the remarkable photoluminescence properties of SnIV(MePDPPh)2 (5s05p0),36 ZrIV(MesPDPPh)2 (4d0),33 and HfIV(MesPDPPh)2 (5d0),76 thorium complex 2b represents a logical and convenient expansion into the f-block elements. Direct comparison of 2b (5f0) to its uranium analogue 2a (5f2) provides a route to probe the influence of energetically accessible 5f orbitals and f–f excited states on luminescence of these complexes. Notably, readily accessible d–d excited states have been well-established to facilitate a rapid nonradiative decay in transition metal complexes.78 Finally, comparing mono- and bis-ligated PDP complexes may illustrate whether two (MesPDPPh)2– ligands are required to achieve interesting optical properties in metal complexes of this type.

We begin our discussion with Th(MesPDPPh)2, due to its relation to other M(MesPDPPh)2 (M = Zr, Hf, Sn) complexes that have been reported previously. Excitation of Th(MesPDPPh)2 in an anhydrous toluene solution at room temperature with UV or visible light below 500 nm resulted in strong photoluminescence (Figure 11). The spectral profile features two broad, overlapping bands, with maxima at 548 and 586 nm. A photoluminescence quantum yield of 42% was determined for 2b at room temperature by the comparative method (ΦPL = 0.42 ± 0.01; Figure S13). This value indicates a high quantum efficiency for complex 2b and is substantially larger than values reported previously for Th(IV) complexes (e.g., [Li(THF)2][Th = NAr3,5-CF3(TriNOx)]; QY = 2.5%).79 The photoluminescence decay for Th(MesPDPPh)2 revealed a lifetime of 304 μs, which we hypothesize to be due to the decay of a long-lived triplet excited state (Figure S14).85

Figure 11.

(a) Molecular structures of complexes 1b and 2b; the photograph includes an image of samples of 1b (left) and 2b (right) irradiated in toluene under 365 nm light. (b) Emission recorded at room temperature for 1b in toluene. (c) Emission recorded at room temperature for 2b in toluene.

It is instructive to compare the photoluminescence properties of 2b with those of its transition metal and main group analogs Zr(MesPDPPh)2, Hf(MesPDPPh)2, and Sn(MePDPPh)2 (Table 3). All three reference compounds exhibit long-lived photoluminescence with lifetimes of hundreds of microseconds to milliseconds and high quantum yields resulting from thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) at room temperature. The similar values for lifetime and quantum yield observed in the present study suggest that a similar photoluminescence mechanism may be at play for Th(MesPDPPh)2. However, there are minor differences in the photophysical data that hint at subtle changes in the electronic structure among the four compounds. These may be a consequence of the difference in valence orbitals for main group, d-block, and f-block elements. Due to the very limited contributions of the Sn p orbitals to the frontier molecular orbitals of Sn(MePDPPh)2, the lowest-energy excited state is predominantly ligand-centered. Consequently, intersystem crossing (ISC) to the triplet state is relatively slow, resulting in the observation of competing prompt and delayed fluorescence at room temperature (kISC ≈ kPF). In contrast, significant d-orbital contributions to the LUMOs of Zr(MesPDPPh)2 and Hf(MesPDPPh)2 introduce LMCT character into the excited state, facilitating rapid ISC (kISC ≫ kPF) and exclusively TADF under ambient conditions. Th(MesPDPPh)2 presents an interesting case because it maximizes heavy-atom effects compared to the remaining three compounds but shows metal contributions that are in-between its main group and transition metal analogs. Highlighting its unusual position within the series, the room-temperature emission spectrum of Th(MesPDPPh)2 exhibits two emission maxima, while the remaining group 4 and 14 compounds show only one broad absorption feature. More detailed studies of the photophysics of Th(MesPDPPh)2 are required to firmly establish the nature of the electronic transitions responsible for emission but are beyond the scope of this initial report.

Table 3. Comparison of Optical Properties of M(RPDPPh)2 Complexes (M = Th, Zr, Hf; R = Mesityl) (M = Sn; R = Methyl).

| Complex | Th(MesPDPPh)2 | Zr(MesPDPPh)2 | Hf(MesPDPPh)2 | Sn(MePDPPh)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λabs (nm) | 462 | 525 | 507 | 464 |

| λem (nm) | 548, 586 | 581 | 558 | 512 |

| ΦPL | 42% | 45% | 41% | 32% |

| τ (ms) | 0.304 | 0.350 | 0.450 | 2.0 |

| Reference | This work | 33 | 76 | 36 |

Next, we investigated the luminescence of the mono-PDP thorium complex to determine the effect of the number of coordinated PDP ligands on the resulting photophysical properties. Excitation of the lowest-energy absorption band in (MesPDPPh)ThCl2(THF) in anhydrous toluene at room temperature resulted in strong photoluminescence (Figure 11). The emission profile is similar to that of 2b, featuring two broad, superimposed bands with maxima at 532 and 568 nm and an energy separation of 1,241 cm–1. Coordination of only one (MesPDPPh)2– ligand in 1b causes a blue shift in the emission profile of the complex in comparison to that of 2b and a slight increase in emission intensity at room temperature. Emission decay kinetics of 1b display similar behavior to that of 2b, with a lifetime of τ = 256 μs. (Figure S14). This observation suggests that the number of coordinated PDP ligands does not have a drastic effect on the decay pathways of these systems. In addition, the quantum yield determined for 1b by the comparative method is comparable to that of 2b at 45% (Φe = 0.45 ± 0.02) (Figure S13).

It is important to note that in contrast to the thorium(IV) congeners, excitation of (MesPDPPh)UCl2(THF) and U(MesPDPPh)2 in anhydrous toluene solutions at room temperature with UV or visible light below 600 nm resulted in no observable emission for both complexes. We believe that the emission decay pathway in the case of the uranium complexes is proceeding through the 5f orbital manifold due to the low-energy 3LMCT transitions present in 1a and 2a, which have been affirmed by TD-DFT calculations.

Conclusions

Here, we report the synthesis and characterization of four actinide complexes of the pyridine dipyrrolide ligand class, (MesPDPPh)AnCl2(THF) and An(MesPDPPh)2 (An = U, Th). The title compounds have been characterized thoroughly through solid- and solution-state methods. The electronic absorption spectra of all complexes are dominated by two high-energy charge transfer bands with predominantly π–π* character, similar to previously reported transition metal and metalloid adducts of the PDP ligand. In the case of the uranium derivatives, evidence for LMCT is observed in the electronic absorption spectrum, characterized by low-energy transitions ranging from 500 to 600 nm, which has also been corroborated with TD-DFT calculations. In contrast, the thorium derivatives exhibit exclusively ILCT and LLCT transitions, consistent with the very negative reduction potential and high energy of the 5f orbitals of Th(IV) ions. Additionally, we report strong room-temperature photoluminescence for the thorium derivatives, with high quantum efficiencies ranging from 40 to 45%. More detailed temperature-dependent and time-resolved studies are required to elucidate the excited-state dynamics of MesPDPPhThCl2(THF) and Th(MesPDPPh)2, which is beyond the scope of this initial report.

Acknowledgments

L.R.V., B.M.H., E.S., and E.M.M. thank the Department of Energy for the financial support of this work, under award DE-SC0020436. L.R.V. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. The WVU High Performance Computing facilities are funded by the National Science Foundation EPSCoR Research Infrastructure Improvement Cooperative Agreement 1003907, the state of West Virginia (WVEPSCoR via the Higher Education Policy Commission), the WVU Research Corporation, and faculty investments. The authors thank Prof. Dave McCamant from the University of Rochester for providing access to his group’s photoluminescence spectrometers.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c04391.

Additional experimental procedures, spectroscopic and crystallographic data, and computational details (PDF)

Author Contributions

L.R.V. synthesized and characterized 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b. B.M.H. and E.S. synthesized and characterized An(PhPDPPh)2 compounds. D.C.L. obtained and analyzed all computational data. W.W.B. determined the crystal structures. C.M. and E.M.M. directed the project. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tsipis A. C.; Kefalidis C. E.; Tsipis C. A. The Role of the 5f Orbitals in Bonding, Aromaticity, and Reactivity of Planar Isocyclic and Heterocyclic Uranium Clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9144–9155. 10.1021/ja802344z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozimor S. A.; Yang P.; Batista E. R.; Boland K. S.; Burns C. J.; Clark D. L.; Conradson S. D.; Martin R. L.; Wilkerson M. P.; Wolfsberg L. E. Trends in Covalency for d- and f-Element Metallocene Dichlorides Identified Using Chlorine K-Edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy and Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12125–12136. 10.1021/ja9015759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidig M. L.; Clark D. L.; Martin R. L. Covalency in f-element complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257 (2), 394–406. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens W. W.; Edelstein N. M.; Magnani N.; Hayton T. W.; Fortier S.; Seaman L. A. Quantifying the σ and π Interactions between U(V) f Orbitals and Halide, Alkyl, Alkoxide, Amide and Ketimide Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (29), 10742–10754. 10.1021/ja403815h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitova T.; Pidchenko I.; Fellhauer D.; Bagus P. S.; Joly Y.; Pruessmann T.; Bahl S.; Gonzalez-Robles E.; Rothe J.; Altmaier M.; Denecke M. A.; Geckeis H. The role of the 5f valence orbitals of early actinides in chemical bonding. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16053. 10.1038/ncomms16053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L. P.; Yang P.; Minasian S. G.; Jilek R. E.; Batista E. R.; Boland K. S.; Boncella J. M.; Conradson S. D.; Clark D. L.; Hayton T. W.; Kozimor S. A.; Martin R. L.; MacInnes M. M.; Olson A. C.; Scott B. L.; Shuh D. K.; Wilkerson M. P. Tetrahalide Complexes of the [U(NR)2]2+ Ion: Synthesis, Theory, and Chlorine K-Edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2279–2290. 10.1021/ja310575j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. B.; Gaunt A. J. Recent Developments in Synthesis and Structural Chemistry of Nonaqueous Actinide Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1137–1198. 10.1021/cr300198m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle S. T. The Renaissance of Non-Aqueous Uranium Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8604–8641. 10.1002/anie.201412168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staun S. L.; Wu G.; Lukens W. W.; Hayton T. W. Synthesis of a heterobimetallic actinide nitride and an analysis of its bonding. Chemical Science 2021, 12, 15519–15527. 10.1039/D1SC05072A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J.; Batista E. R.; Boland K. S.; Bone S. E.; Bradley J. A.; Cary S. K.; Clark D. L.; Conradson S. D.; Ditter A. S.; Kaltsoyannis N.; Keith J. M.; Kerridge A.; Kozimor S. A.; Löble M. W.; Martin R. L.; Minasian S. G.; Mocko V.; La Pierre H. S.; Seidler G. T.; Shuh D. K.; Wilkerson M. P.; Yang P. Energy-Degeneracy-Driven Covalency in Actinide Bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17977–17984. 10.1021/jacs.8b09436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minasian S. G.; Keith J. M.; Batista E. R.; Boland K. S.; Clark D. L.; Kozimor S. A.; Martin R. L.; Shuh D. K.; Tyliszczak T. New evidence for 5f covalency in actinocenes determined from carbon K-edge XAS and electronic structure theory. Chemical Science 2014, 5, 351–359. 10.1039/C3SC52030G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold P. L.; Love J. B.; Patel D. Pentavalent uranyl complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1973–1978. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denning R. G. Electronic Structure and Bonding in Actinyl Ions and their Analogs. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 4125–4143. 10.1021/jp071061n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho I. T.; Zhang Z.; Ishida M.; Lynch V. M.; Cha W.-Y.; Sung Y. M.; Kim D.; Sessler J. L. A Hybrid Macrocycle with a Pyridine Subunit Displays Aromatic Character upon Uranyl Cation Complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4281–4286. 10.1021/ja412520g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler J. L.; Vivian A. E.; Seidel D.; Burrell A. K.; Hoehner M.; Mody T. D.; Gebauer A.; Weghorn S. J.; Lynch V. Actinide expanded porphyrin complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 216–217, 411–434. 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00395-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J. T.; He Q.; Anguera G.; Moore M. D.; Ke X.-S.; Lynch V. M.; Sessler J. L. Synthesis and characterization of a dipyriamethyrin-uranyl complex. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 4981–4984. 10.1039/C7CC01674C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguera G.; Brewster J. T. II; Moore M. D.; Lee J.; Vargas-Zúñiga G. I.; Zafar H.; Lynch V. M.; Sessler J. L. Naphthylbipyrrole-Containing Amethyrin Analogue: A New Ligand for the Uranyl (UO22+) Cation. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 9409–9412. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J. T.; Root H. D.; Mangel D.; Samia A.; Zafar H.; Sedgwick A. C.; Lynch V. M.; Sessler J. L. UO22+-mediated ring contraction of pyrihexaphyrin: synthesis of a contracted expanded porphyrin-uranyl complex. Chemical Science 2019, 10, 5596–5602. 10.1039/C9SC01593K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J. T.; Root H. D.; Mangel D.; Samia A.; Zafar H.; Sedgwick A. C.; Lynch V. M.; Sessler J. L. Correction: UO22+-mediated ring contraction of pyrihexaphyrin: synthesis of a contracted expanded porphyrin-uranyl complex. Chemical Science 2019, 10, 7119–7119. 10.1039/C9SC90138H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J. T. II; Zafar H.; Root H. D.; Thiabaud G. D.; Sessler J. L. Porphyrinoid f-Element Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 32–47. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J. T. II; Mangel D. N.; Gaunt A. J.; Saunders D. P.; Zafar H.; Lynch V. M.; Boreen M. A.; Garner M. E.; Goodwin C. A. P.; Settineri N. S.; Arnold J.; Sessler J. L. In-Plane Thorium(IV), Uranium(IV), and Neptunium(IV) Expanded Porphyrin Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (44), 17867–17874. 10.1021/jacs.9b09123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie B. E.; Douair I.; Maron L.; Love J. B.; Arnold P. L. Selective oxo ligand functionalisation and substitution reactivity in an oxo/catecholate-bridged UIV/UIV Pacman complex. Chemical Science 2020, 11, 7144–7157. 10.1039/D0SC02297G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A. L.; Buckley H. L.; Lukens W. W.; Arnold J. Synthesis and Characterization of Thorium(IV) and Uranium(IV) Corrole Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13965–13971. 10.1021/ja407203s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komine N.; Buell R. W.; Chen C.-H.; Hui A. K.; Pink M.; Caulton K. G. Probing the Steric and Electronic Characteristics of a New Bis-Pyrrolide Pincer Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 1361–1369. 10.1021/ic402120r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsche D.; Miehlich M. E.; Searles K.; Gouget G.; Zolnhofer E. M.; Fortier S.; Chen C.-H.; Gau M.; Carroll P. J.; Murray C. B.; Caulton K. G.; Khusniyarov M. M.; Meyer K.; Mindiola D. J. Unusual Dinitrogen Binding and Electron Storage in Dinuclear Iron Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 8147–8159. 10.1021/jacs.0c01488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda A. S.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Redox Chemistry of Bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine Chromium and Molybdenum Complexes: An Experimental and Density Functional Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 1919–1934. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakey B. M.; Darmon J. M.; Zhang Y.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Synthesis and Electronic Structure of Neutral Square-Planar High-Spin Iron(II) Complexes Supported by a Dianionic Pincer Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 1252–1266. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakey B. M.; Darmon J. M.; Akhmedov N. G.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Reactivity of Pyridine Dipyrrolide Iron(II) Complexes with Organic Azides: C-H Amination and Iron Tetrazene Formation. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 11028–11042. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakey B. M.; Leary D. C.; Rodriguez J. G.; Martinez J. C.; Vaughan N. B.; Darmon J. M.; Akhmedov N. G.; Petersen J. L.; Dolinar B. S.; Milsmann C. Effects of 2,6-Dichlorophenyl Substituents on the Coordination Chemistry of Pyridine Dipyrrolide Iron Complexes. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie 2021, 647, 1503–1517. 10.1002/zaac.202100117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakey B. M.; Leary D. C.; Xiong J.; Harris C. F.; Darmon J. M.; Petersen J. L.; Berry J. F.; Guo Y.; Milsmann C. High Magnetic Anisotropy of a Square-Planar Iron-Carbene Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 18575–18588. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. A Luminescent Zirconium(IV) Complex as a Molecular Photosensitizer for Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13115–13118. 10.1021/jacs.6b05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Leary D. C.; Belldina A. M.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Effects of Ligand Substitution on the Optical and Electrochemical Properties of (Pyridinedipyrrolide)zirconium Photosensitizers. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 14716–14730. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Lee T. S.; Favale J. M.; Leary D. C.; Petersen J. L.; Scholes G. D.; Castellano F. N.; Milsmann C. Delayed fluorescence from a zirconium(IV) photosensitizer with ligand-to-metal charge-transfer excited states. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 345–352. 10.1038/s41557-020-0430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Sheykhi S.; Zhang Y.; Milsmann C.; Castellano F. N. Low power threshold photochemical upconversion using a zirconium(IV) LMCT photosensitizer. Chemical Science 2021, 12, 9069–9077. 10.1039/D1SC01662H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S.; Dash C. One-pot Tandem Heck alkynylation/cyclization reactions catalyzed by Bis(Pyrrolyl)pyridine based palladium pincer complexes. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131350. 10.1016/j.tet.2020.131350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda A. S.; Lee T. S.; Rosko M. C.; Petersen J. L.; Castellano F. N.; Milsmann C. Long-Lived Photoluminescence of Molecular Group 14 Compounds through Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 7338–7348. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natrajan L. S. Developments in the photophysics and photochemistry of actinide ions and their coordination compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1583–1603. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond M. P.; Cornet S. M.; Woodall S. D.; Whittaker D.; Collison D.; Helliwell M.; Natrajan L. S. Probing the local coordination environment and nuclearity of uranyl(VI) complexes in non-aqueous media by emission spectroscopy. Dalton Transactions 2011, 40, 3914–3926. 10.1039/c0dt01464h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortu F.; Randall S.; Moulding D. J.; Woodward A. W.; Kerridge A.; Meyer K.; La Pierre H. S.; Natrajan L. S. Photoluminescence of Pentavalent Uranyl Amide Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13184–13194. 10.1021/jacs.1c05184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R.; Mondal J. A.; Ghosh H. N.; Palit D. K. Ultrafast Dynamics of the Excited States of the Uranyl Ion in Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5263–5270. 10.1021/jp912039r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuéry P.; Atoini Y.; Kusumoto S.; Hayami S.; Kim Y.; Harrowfield J. Optimizing Photoluminescence Quantum Yields in Uranyl Dicarboxylate Complexes: Further Investigations of 2,5-, 2,6- and 3,5-Pyridinedicarboxylates and 2,3-Pyrazinedicarboxylate. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 4391–4400. 10.1002/ejic.202000803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann J. A.; Suttle J. F.; Hoekstra H. R. Uranium(IV) Chloride. Inorganic Syntheses 1957, 5, 143–145. 10.1002/9780470132364.ch39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantat T.; Scott B. L.; Kiplinger J. L. Convenient access to the anhydrous thorium tetrachloride complexes ThCl4(DME)2, ThCl4(1,4-dioxane)2 and ThCl4(THF)3.5 using commercially available and inexpensive starting materials. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 919–921. 10.1039/b923558b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. A.; Kiernicki J. J.; Fanwick P. E.; Bart S. C. New Benzylpotassium Reagents and Their Utility for the Synthesis of Homoleptic Uranium(IV) Benzyl Derivatives. Organometallics 2015, 34, 2889–2895. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CrysAlisPro; Rigaku, 2021.

- Sheldrick G. SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallographica Section C 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2012, 2, 73–78. 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2022, 12, e1606. 10.1002/wcms.1606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahtras O.; Almlöf J.; Feyereisen M. W. Integral approximations for LCAO-SCF calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 213, 514–518. 10.1016/0009-2614(93)89151-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. An improvement of the resolution of the identity approximation for the formation of the Coulomb matrix. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1740–1747. 10.1002/jcc.10318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wüllen C. Molecular density functional calculations in the regular relativistic approximation: Method, application to coinage metal diatomics, hydrides, fluorides and chlorides, and comparison with first-order relativistic calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 392–399. 10.1063/1.476576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A.; Neese F. All-Electron Scalar Relativistic Basis Sets for the Actinides. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 677–684. 10.1021/ct100736b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F.; Wennmohs F.; Hansen A.; Becker U. Efficient, approximate and parallel Hartree-Fock and hybrid DFT calculations. A ‘chain-of-spheres’ algorithm for the Hartree-Fock exchange. Chem. Phys. 2009, 356, 98–109. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.10.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helmich-Paris B.; de Souza B.; Neese F.; Izsák R. An improved chain of spheres for exchange algorithm. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 104109. 10.1063/5.0058766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. Efficient and accurate approximations to the molecular spin-orbit coupling operator and their use in molecular g-tensor calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 034107. 10.1063/1.1829047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ratés M.; Neese F. Effect of the Solute Cavity on the Solvation Energy and its Derivatives within the Framework of the Gaussian Charge Scheme. J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41, 922–939. 10.1002/jcc.26139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche A.-R. Gabedit—A graphical user interface for computational chemistry softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 174–182. 10.1002/jcc.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio L. R.; Hakey B. M.; Brennessel W. W.; Matson E. M. Quantitative U = O bond activation in uranyl complexes via silyl radical transfer. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 11244–11247. 10.1039/D2CC04424B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakey B. M.; Leary D. C.; Lopez L. M.; Valerio L. R.; Brennessel W. W.; Milsmann C.; Matson E. M. Synthesis and Characterization of Pyridine Dipyrrolide Uranyl Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 6182–6192. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. L.; Mokhtarzadeh C. C.; Lever J. M.; Wu G.; Hayton T. W. Facile Reduction of a Uranyl(VI) β-Ketoiminate Complex to U(IV) Upon Oxo Silylation. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5105–5112. 10.1021/ic200387n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernicki J. J.; Cladis D. P.; Fanwick P. E.; Zeller M.; Bart S. C. Synthesis, Characterization, and Stoichiometric U-O Bond Scission in Uranyl Species Supported by Pyridine(diimine) Ligand Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11115–11125. 10.1021/jacs.5b06217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst J. R.; Bell N. L.; Zegke M.; Platts L. N.; Lamfsus C. A.; Maron L.; Natrajan L. S.; Sproules S.; Arnold P. L.; Love J. B. Inner-sphere vs. outer-sphere reduction of uranyl supported by a redox-active, donor-expanded dipyrrin. Chemical Science 2017, 8, 108–116. 10.1039/C6SC02912D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; McKearney D.; Leznoff D. B. Structural Diversity of F-Element Monophthalocyanine Complexes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 1027–1031. 10.1002/chem.201904535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobbe B. C.; Powell D. R.; Thomson R. K. Schiff base thorium(iv) and uranium(iv) chloro complexes: synthesis, substitution and oxidation chemistry. Dalton Transactions 2017, 46, 4888–4892. 10.1039/C7DT00580F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernicki J. J.; Newell B. S.; Matson E. M.; Anderson N. H.; Fanwick P. E.; Shores M. P.; Bart S. C. Multielectron C-O Bond Activation Mediated by a Family of Reduced Uranium Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 3730–3741. 10.1021/ic500012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K.; Hoffmann R. Bent cis d0 MoO22+ vs. linear trans d0f0 UO22+: a significant role for nonvalence 6p orbitals in uranyl. Inorg. Chem. 1980, 19, 2656–2658. 10.1021/ic50211a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalampillai A.; Crewdson P.; Korobkov I.; Gambarotta S. Ring Opening and C-O and C-N Bond Cleavage by Transient Reduced Thorium Species. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3856–3866. 10.1021/om060454q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leary D. C.; Martinez J. C.; Gowda A. S.; Akhmedov N. G.; Petersen J. L.; Milsmann C. Speciation and Photoluminescent Properties of a 2,6-Bis(pyrrol-2-yl)pyridine in Three Protonation States. ChemPhotoChem. 2023, 7, e202300094. 10.1002/cptc.202300094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S.Introduction to the Actinides. Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry; Wiley, 2006; pp 145–153. [Google Scholar]