The NHS was established as a compromise between key parties; it allowed those patients who could afford it to have access to both private health care and the NHS and it permitted consultants to have access to income from private practice while working in the NHS. This safety valve for excess demand was developed contrary to the founding principles of equity, but it has been a feature of health care in the United Kingdom ever since; it allows more affluent patients to circumvent the periodic funding crises in the NHS while maintaining their support for health care funded by taxes. However, the share of total healthcare spending contributed by the private sector has risen steadily. This trend has led some commentators to argue that the NHS is not sustainable, primarily because funding through taxation will lead to an increasing gap between the demand for and supply of health care. Alternatives to the NHS would involve requiring a larger private contribution to the costs of health care but such systems require complex regulation and seem to produce inequities that reveal the specific interests of their proponents. In contrast, expanding the funding of the NHS in line with increases in the gross national product is affordable and broadly equitable.

Whether the UK compromise between public and private interests will be sustained cannot be predicted. Recent developments suggest that major change may occur unintentionally through the cumulative effects of small or unplanned changes, or both, or result from applying policy thinking from other fields of welfare, such as social security reform.

Summary points

The advent of the NHS did not lead to the abolition of private finance for or the private provision of health care in the United Kingdom

Shares of total healthcare spending and healthcare provision contributed by the private sector have risen steadily since the end of the 1960s

Several recent policy developments may cumulatively lead to a radically different balance of public and private finance and insurance

Alternatives to the NHS that involved a larger share of private financing would require complex regulation and would be less equitable than current arrangements

Health care was rationalised, not nationalised

There is a tendency in commentary on the NHS to discuss it as though it is the only healthcare system in the United Kingdom but this has never been an accurate reflection of the situation. The early history of the NHS shows clearly that the newly nationalised service did not represent a clean break with the past even though it rapidly consigned private health care to a residual role that served a small minority of the population.1 Rather, it was a partial rationalisation of what existed, conditioned by a need to reassure and encourage, rather than coerce, a number of conservative professional interest groups to participate. Thus from the outset the NHS was entangled in a wide range of relationships (with both private finance and those who supplied health care and related goods and services privately) which compromised its goal of ensuring that health services were available exclusively on the basis of need.

Over the 50 years some of the large scale features of this compromise have remained remarkably stable, both within the NHS and in its relationships with the private sector (box next page). Thus the 1946 act which founded the NHS represents a long term compromise between the interests of the state and the interests of professional, commercial, middle income, and upper income groups. This compromised fudged the equity principle in the 1946 act by permitting, and at times encouraging, private health care to develop alongside the NHS as a safety valve for people with the resources to make additional provision for themselves. The question now is whether the compromise will continue to protect the NHS into the 21st century.

Continuity and change

Despite successive funding crises threatening the comprehensiveness and sustainability of the NHS, an increasing level of criticism of its apparently poor performance, and the tolerance of private health care by successive governments the main developments in NHS policy since 1948 have done little directly to undermine the fundamental principles of the NHS as being predominantly funded by taxes and providing universal access to services. Instead, changes in policy have attempted, as in the case of the internal market,2 to improve efficiency and responsiveness to patients’ needs within a publicly funded system.

Over time there have been shifts in the perception of what is possible and desirable in the future. Perhaps the biggest change has been in the perception that there is a widening gap between what the NHS might be able to provide with more resources and what it can provide at current levels of funding. For example, the increasing numbers of high cost drugs that the NHS is required to purchase lead to contentious priority decisions and fuel the demand for more spending. One result of this perceived gap is that successive government changes to the NHS have not reduced the attraction of private health care. Far from private practice diminishing as the NHS has grown, the private sector has become steadily more important both in financing and supplying health care, but this has not threatened the founding principles of the NHS.3 The box below summarises some of the main trends in the balance between private and public finance and the provision of health services.

Public-private ties established with the founding of the NHS

General practitioners work as independent contractors, not salaried employees

Specialist doctors and other professionals can maintain both NHS and private practices

NHS pay beds (essentially private beds in NHS hospitals which allow the trust to charge for the bed and consultants to charge separately for services)

Prescription and other charges to users for NHS services

Patient access to both NHS and private treatment, sometimes for the same condition; access to private treatment on the basis of ability to pay rather than need

Reliance of the NHS on pharmaceutical and other industries to develop new products with the NHS contributing resources to development and testing

Arguments for changes in the NHS

The NHS continues to have high levels of public support. Seventy seven per cent of the population support the principle of a health service available to all, although this does not necessarily mean that they oppose people having the choice of paying for private health care.8 Although it is difficult to believe when you are on an NHS waiting list, people are more satisfied with arrangements in the United Kingdom than are people in either Canada or the United States.9 The United Kingdom also compares favourably internationally in terms of fairness of funding, equality of access, and efficiency.10

Nevertheless, arguments persist that a higher share of private funding in a mixed economy of public and private care is inevitable and desirable. Critics tend to argue that a publicly funded system, particularly one funded through general taxation, cannot provide the volume and standard of health care that an increasingly affluent, aged, and sophisticated population wants (despite the fact that we cannot determine objectively what level of spending is correct). The main difference between the United Kingdom and other comparable countries lies not in the amount of public funding for health care but in the lower level of private funding. There is a clear gap between NHS resources and demand, shown particularly clearly in the provision of expensive new drugs such as interferon beta. Yet more public spending is not an option if the United Kingdom is to remain internationally competitive in increasingly global markets, and additional spending is political suicide for any government. If more affluent people are only able to spend more of their money on health care provided outside the NHS then, inevitably, the private sector will and should grow to meet the unmet demand in the public sector.

Trends in the mix of public and private financing

Total spending in the NHS and in the private healthcare sector rose from 3.9% of gross domestic product in 1960 to 7.1% of gross domestic product in 19924

The private sector’s share of total spending on health care rose from around 3% in the 1960s to 14% in 1985 and to 16% in 19923

Public and private expenditure on private hospital care and private nursing home care increased from 9.9% of total healthcare expenditure in 1986 to 19.9% in 19965

The number of subscribers to private heath insurance policies increased from 2.45 million in 1986 to 3.17 million in 19966

Payments by patients for NHS services rose from £35m in 1960 to £919m in 19967

Investment in new hospitals under the private finance initiative announced since 1 May 1997 was £660m (Department of Health press release 98/123)

Governments, including the current one, have responded to this argument by vowing to keep taxes and public spending down which further encourages the suspicion that institutions like the NHS are unsustainable and that more private finance is the only alternative. A range of solutions to the perceived financial unsustainablilty of the NHS has been proposed. For example, Hoffmeyer and McCarthy11 propose a model to replace the NHS and meet increasing demand with a guaranteed package of health care for all; their model comprises competing health insurance agencies, compulsory insurance, premiums based on income and (health) risk, a central fund designed to share the costs of high risk groups, safety nets for individuals unable to afford or find insurance, providers competing for the business of insurance agency purchasers, and a prohibition against insurers excluding whole groups of patients or insisting on unreasonable terms to avoid risk.

This model has something in common with the different forms of insurance that were available in the United Kingdom before the formation of the NHS. The central ideas are that patients can choose between different packages and insurers, and more affluent patients can insure themselves for higher levels of care, which would increase the level of funding for health care beyond that permitted by successive parsimonious governments. Behind the scenes the government would attempt to ensure that each insurer had roughly equal funds in relation to the requirements of those enrolled in their plan.

But is it the case that we cannot afford the NHS, and would it be a good thing to abandon the basic architecture of health care in the United Kingdom for something new? Analysis indicates that given even conservative estimates of economic growth the United Kingdom can continue to pay for the welfare state and the NHS through taxation, if it chooses.12 Whether we should spend more is a separate question to which there is no objective answer.

As to whether the United Kingdom should opt for a more explicitly mixed system with much more private finance and a basic publicly subsidised sector for the less well off, 40 years’ experience from all over the world cautions against it.13 Such systems, like that in the United States, tend to perform poorly in terms of public satisfaction, health outcomes, efficiency, access, and equity of finance, and are difficult to manage and regulate. They do, however, tend to increase expenditure, jobs, and incomes in the health sector. For this reason, they are supported by providers and private insurers. They are also attractive to upper income taxpayers since they enable such people to benefit at the expense of poorer people, because user charges and the cost of private insurance impose more of a burden on those who are poor and who are more likely to make higher use of services. The greater the reliance on private finance and the less the reliance on taxation or social insurance, the greater the opportunity for people to purchase more services for themselves without having to pay to support a similar standard of care for everyone else. Since those in need in any one year will be a small proportion of the population—and they will be disproportionately elderly people and those with chronic illnesses, who are least able to pay—private finance tends to improve access to care for those who are least likely to need it. Healthcare financing changes in the United Kingdom would thus have profound consequences for the equitable distribution of resources.

The shape of things to come

Irrespective of the merits of these arguments—and they have made little headway in most countries that have systems providing universal access to care—there is little doubt that a more mixed economy is emerging in the United Kingdom (box), albeit not always as a direct result of explicit reform of health policy. Further changes could occur simply through the accumulation of seemingly separate smaller scale changes which would further reduce the contribution of publicly funded health services; the box summarises a few of these changes.

Developments that are altering the mix of financing for health care

Charging for eye tests on the NHS

Moving NHS dental care into the private sector

Commercial funding for all major NHS capital schemes

Changes in social security leading to a requirement for personal insurance against accident and sickness

Plans for compulsory private insurance for long term care

Proposals from some NHS healthcare trusts for additional contributions from local people

Government plans to charge insurers for the full cost of NHS treatment of motorists and passengers involved in road accidents

Change may also come about unintentionally if the proposals contained in the government white paper The New NHS,14 which sets out Labour’s plans for the abolition of the internal market, are acted on. One theory is that the unwitting combination of the new primary care groups (groups of practices responsible both for commissioning hospital and community health services and developing general practitioner services) in England and the use of the private finance initiative (a scheme under which private finance is used to build hospitals which are then leased back to the NHS ) will lead to something akin to an American style system developing in the United Kingdom; general practitioners might in effect function outside the NHS and this could possibly trigger an unplanned shift to a system in which patients choose to enrol with a range of competing primary care based total healthcare plans using vouchers from the NHS together with private insurance to cover additional services.15

Some of the changes would emphasise more strongly the difference between the privately insured haves and the publicly subsidised have nots, along the lines of the American model,16 which could undermine the current majority support for the NHS. However, this does not seem to be the intention of the government, which has signalled that its priority is to support the NHS and to reduce the likelihood that people will use the private sector by making the reduction of NHS waiting lists a priority.18 Like its predecessor, this government’s aim seems to be to improve efficiency within the publicly funded system using management techniques borrowed from the private sector.

Conclusion

The overall position at the moment is one where most of the main elements of the 1946 compromise settlement remain in place—for better or for worse. The fact that the compromise was not simply between public and private interests but was more complex has made it difficult to change. Gazing into a crystal ball is rarely rewarding but it seems that the NHS may move in one of at least three different directions. In the first scenario key elements of the 1946 settlement, including the privileged position of consultants, will be renegotiated, with sources of finance staying broadly the same. The rapid evolution of the debate on clinical self regulation, particularly following the case in Bristol in which three surgeons were accused of continuing to operate despite high mortality,19 suggests that this may already be happening. The second scenario is of more radical change, whether planned or unplanned, with a far larger role for private finance. Some of the signs suggest that this is not out of the question. The third scenario, which tends already to be the outcome of the periodic crises in the NHS, is that it will continue to muddle through, with its current least worst settlement largely in place. As time goes on and if the private sector continues to grow this third path may become less likely, since an increasing proportion of the population will come to rely on the private sector for more of its health care.

Maybe the most important development will be in our sensibilities. Having been told for so long that change is inevitable, the prospect of change does not seem quite so alarming, even though the evidence that it will solve the enduring problems of health care in the United Kingdom is lacking.

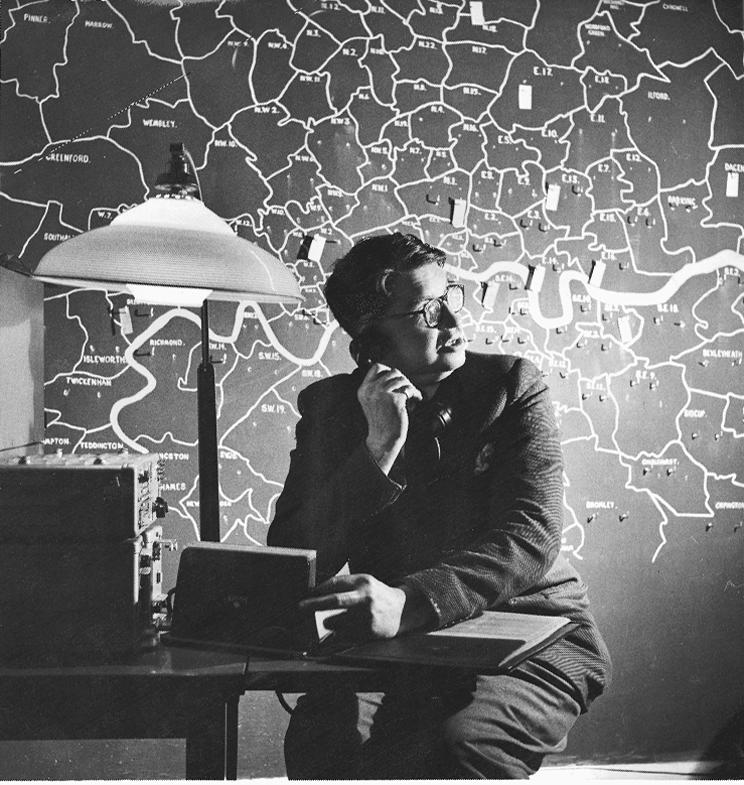

Figure.

Public and private have always coexisted in the NHS: an early general practitioner deputising service

Acknowledgments

Thanks for helpful comments, but no responsibility for the contents of this paper, are due to Tony Harrison and Sean Boyle.

References

- 1.Rivett G. From cradle to grave: fifty years of the NHS. London: King’s Fund; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Secretaries of State. Working for patients. London: HMSO; 1989. (Cm 555.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Propper C. Who pays for and who gets health care? London: Nuffield Trust; 1998. (Health economics series, no. 5.) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health care reform: the will to change. Paris: OECD; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laing W. Laing’s review of private healthcare. London: Laing and Buisson; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of British Insurers. The private medical insurance market. London: ABI; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuigan S. Office of Health Economics compendium of health statistics 1997. London: OHE; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Judge K, Mulligan J-A, New B. The NHS: new prescriptions needed? In: Jowell R, Curtice J, Park A, Brook L, Thomson K, Bryson C, editors. British social attitudes, the 14th report: the end of Conservative values? Aldershot: Ashgate/Social and Community Planning Research; 1997. pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blendon RJ, Leitman R, Morrison I, Donelan K. Satisfaction with health systems in ten nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1990;9:185–192. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Equity in the finance of health care: some international comparisons. J Health Economics. 1992;11:361–387. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(92)90012-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmeyer UK, McCarthy TR. Financing health care. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hills J. The future of welfare: a guide to the debate. Rev ed. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans RG. Health care reform: who’s selling the market and why? J Public Health Med. 1997;19:45–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollock A. The American way. Health Serv J. 1998;108:28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinhardt U. A social contract for 21st century health care: three-tier health care with bounty hunting. Health Economics. 1996;5:479–499. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199611)5:6<479::AID-HEC228>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milburn A. The chance we’ve been waiting for. Health Serv J. 1998;108:20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treasure T. Lessons from the British case. BMJ. 1998;316:1685–1686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]