The NHS is 50 years old. Every government since 1948 has re-invoked its founding principles, but there is less agreement about how services based on these principles should be organised. Alongside remarkable stability in the espoused purpose of the NHS there has been almost constant structural change. Health action zones and primary care organisations are the latest offerings. There is a paper mountain of advice on reforms, restructuring, and managing change. Yet many behaviours do not change. The puzzle is why the NHS has been so unchanging, given the barrage of attempts to “reform” it.

Some things have changed, of course, in as much as complex systems can be changed from outside. Bits have been knocked off and elements have been downsized or re-engineered, but these changes have been resisted by most “insiders.” These insiders have been successfully self ordering so that much of what happens in the NHS is unchanged in nature, if reduced in quantity. During all this investment in managing change, most insiders have not come to want the NHS to be different.

In this anniversary year it may not be enough simply to restate values and purpose. A more fruitful approach may be to focus on the behaviour of this complex system and to try to understand what creates the internal dynamics and maintains enduring patterns of order and behaviour.

Summary points

Despite considerable structural change and numerous attempts at “reform,” the underlying nature of the NHS has remained remarkably stable and many behaviours have not changed

This stability could be explained by the stability of the guiding principles that shape behaviour in the NHS—“Can do, should do,” “Doing means treatment,” “Treatment should fix it,” and “I am responsible”

These principles, though once appropriate, may now be reducing the NHS’s adaptive capacity

To allow proper reform of the NHS, we have to engage directly with these guiding principles and change them, rather than simply changing the organisational structure

Commonly, change is understood in terms of top-down plans. The centre has a strategic “map,” and this is translated into organisational structures that are designed to fit, like the pieces of a jigsaw. But this has only a limited influence on the way that individual staff work with patients. Another approach is to look for guiding principles that are compatible with both the purpose of the NHS and the daily decision making that takes place in millions of patient contacts. If we could describe what gives rise to the behaviour patterns of the NHS this might help us decide what we want to retain and what we want to adapt to take us through the next 50 years. We can hypothesise that, if there are guiding principles that shape behaviour in the NHS, then the NHS can be reformed only by engaging with and changing the principles themselves.

Principles that shape behaviour

Can we describe the principles that shape the behaviour which we identify with the NHS? Are they still useful? May they now be reducing the NHS’s adaptive capacity, although they were once useful? What are the appropriate guiding principles for a modern, publicly funded, national health service? We have identified some principles that we believe, taken together, can describe current patterns of behaviour in the NHS:

Can do, should do

Doing means treatment

Treatment should fix it

I am responsible

Can do, should do

This reflects the way in which the original statement of purpose that the NHS provide a comprehensive health service is converted into everyday meaning that the NHS should provide health care on the basis of “what can be done should be done” (personal communication, M Flatau, Complexity and Management Centre, University of Hertfordshire). In 1948 this principle made sense: there were postwar shortages of everything (so more was better), far fewer available treatments, and a widespread belief that science produced unalloyed benefits. Fifty years later the same conditions do not apply: the range of possible medical interventions could swallow a huge section of our gross domestic product (GDP), we are more wary of technology,1 and treatment can be seen as unkind, unnecessary, ineffective, inappropriate, or unethical.2

Cochrane suggested that the NHS should provide all effective treatments free of charge.3 But does this mean do everything that is effective or does it mean do everything that is appropriate? Or, since there can surely be no guarantee that the NHS budget will be allowed to match that level of service, does it mean do everything that is on the authorised list of NHS treatments?

The introduction of purchasing in the 1980s has revealed that there may be two self ordering systems within the NHS—crudely, one represented by clinicians and patients and one by managers and public health practitioners. “Can do, should do” is a principle based on rights. For individual therapeutic decisions it probably still provides a reasonable basis for action, although “Can do, should be available” might be closer to the balance required between advantage and risk. In contrast, the public health principle of do what produces the maximum health gain with the available resources is founded on a goal based interpretation of distributive justice. This is not a dilemma when one or other horn presents the best solution. It is a paradox in which resolution requires the adequate expression of both elements.

From this perspective it may be time for the NHS to limit “Can do, should do” to a set of interventions recognised by all as effective and necessary for social cohesion and guaranteed to be universally available without delay. Any additional spending on health care would then be governed by the principle of maximising the health gain for the population.

Doing means treatment

In the 1940s the NHS was part of the creation of the welfare state, perhaps even its flagship. The motivation for change was not the unequal standardised mortality ratios of different social classes. The motivation was to make medical care available to everyone, which has become internalised as “Doing means treatment.” For practitioners and managers, equity has come to mean equal treatment rather than the agenda of redistributive social justice of the 1940s.

There is no lack of evidence linking poor diet and poor housing, for example, to poor health,4,5 but this has little impact on behaviour in the NHS. The potential benefits of disease prevention and health promotion are uncontested. The principle of “Doing means treatment” has allowed preventive therapies and health promoting activities to be accepted at a personal level. But this principle may be responsible for the fact that 50 years later the NHS has not tackled the major determinants of ill health that require collective action. How will the NHS respond to today’s agenda from the Social Exclusion Unit and the government green paper Our Healthier Nation?6

Treatment should fix it

Most healthcare professionals are motivated to make people well. The hope that they can do so leads to the belief that treatment should fix it and, thus, that the product is cure. In 1948 there was a legacy of ill health that had never been treated. It was reasonable to assume that once treatment got under way the population would become healthier. Fifty years later this principle is no longer advantageous if the system is designed to deal with acute illness but still deals inadequately with chronic illness. The application of this principle over the years has resulted in relative underinvestment in caring and rehabilitative services. It is no accident that the Cinderella services remain Cinderellas.

I am responsible

Part of the “genetic code” of professional identity is the principle “I am responsible.” Professionals have to be able to decide and act autonomously. In 1948 many interventions could be handled by a single professional, and if that professional took responsibility the job would be responsibly done. Fifty years later the “I” can be a problem when it excludes others from sharing that responsibility. As technology has advanced and specialisation progressed, interprofessional working has become the norm. Responsibility has to be shared with patients too, many of whom are looking for a partnership with clinicians in deciding their treatment and care. And now the white paper The New NHS proposes something called “a duty of partnership” on all organisations in the NHS.7

When “I am responsible” leads to many different individuals struggling for dominance, team working and interagency cooperation become fraught. So called solutions turn out to have more to do with ownership than collaboration, which may go some way to explaining the NHS mania for reorganising control structures. How would it work if this principle were replaced by “I am responsible in partnership with others”? This would support working across boundaries to build relationships and other sorts of management activity. And we might see mainstream money, not just peripheral budgets, linked to working in partnership. What would it mean for professional interactions with patients, and with other professionals, to be guided by the principle “The system is responsible and I will behave responsibly”? For a start, we might expect a new emphasis on co-providing, in which professional-patient interactions would be seen as meetings between experts where the knowledge of experience is valued alongside professional expertise.8

Conclusions

Management of change in the NHS often consists of attempts to control behaviour by changing the organisational structure. I suggest that order, in contrast with control, may arise from guiding principles that reflect the meaning and purpose people ascribe to their work in the NHS. Changing to a new pattern of order may be achieved by engaging directly with these guiding principles.9

People are exploring ways of working that allow intervention at this level.10 These include, but are not limited to, large group interventions,11 and they share several key features:

People come together from a range of different perspectives

People spend enough time together to move beyond first impressions

People engage in conversations that generate possibilities but don’t start with problem solving.

You can start the process yourself by talking about “Can do, should do” over a cup of coffee with somebody you don’t usually work with.

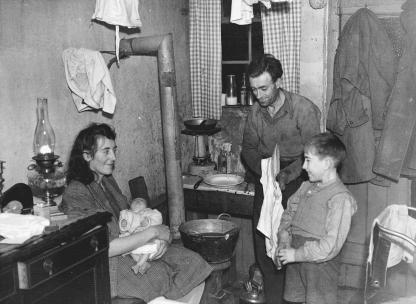

Figure.

The NHS’s concentration on treatment allowed it to ignore determinants of health such as poverty and ill housing

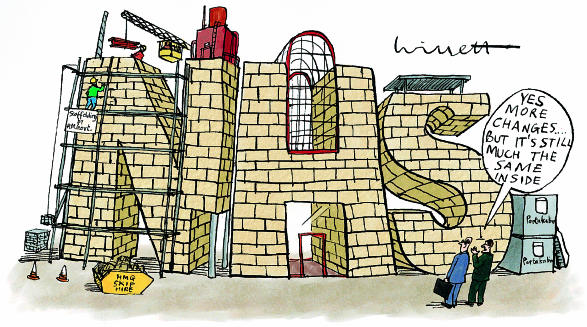

Figure.

Acknowledgments

The ideas in this article are from work in progress in the Urban Health Partnership based at the King’s Fund (members Martin Fischer, Pat Gordon, Diane Plamping, Julian Pratt). The partnership is developing a whole system approach to interagency partnership and public participation.

Footnotes

Funding: King’s Fund, Baring Foundation, St Thomas’s Trustees, NHSE North Thames. Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Beck U. Risk society: towards a new modernity. London: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennett B. High technology medicine: benefits and burdens. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochrane AL. Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DHSS Working Group on Inequalities in Health. The Black report. London: DHSS; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrose P. The real cost of poor homes. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. Our healthier nation: a contract for health. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popay J, Williams G. Public health research and lay knowledge. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:759–768. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratt J, Kitt I. Going home from hospital—a new approach to developing strategy. Br J Health Care Manage (in press).

- 10.Pratt J, Plamping D, Gordon P. Working whole systems. London: King’s Fund (in press).

- 11.Bunker BB, Alban BT. Large group interventions—engaging the whole system for rapid change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]