Abstract

Purpose

Triggers have been developed internationally to identify intensive care patients with palliative care needs. Due to their work, nurses are close to the patient and their perspective should therefore be included. In this study, potential triggers were first identified and then a questionnaire was developed to analyse their acceptance among German intensive care nurses.

Methods

For the qualitative part of this mixed methods study, focus groups were conducted with intensive care nurses from different disciplines (surgery, neurosurgery, internal medicine), which were selected by convenience. Data were analysed using the “content-structuring content analysis” according to Kuckartz. For the quantitative study part, the thus identified triggers formed the basis for questionnaire items. The questionnaire was tested for comprehensibility in cognitive pretests and for feasibility in a pilot survey.

Results

In the qualitative part six focus groups were conducted at four university hospitals. From the data four main categories (prognosis, interprofessional cooperation, relatives, patients) with three to 15 subcategories each could be identified. The nurses described situations requiring palliative care consults that related to the severity of the disease, the therapeutic course, communication within the team and between team and patient/relatives, and typical characteristics of patients and relatives. In addition, a professional conflict between nurses and physicians emerged. The questionnaire, which was developed after six cognitive interviews, consists of 32 items plus one open question. The pilot had a response rate of 76.7% (23/30), whereby 30 triggers were accepted with an agreement of ≥ 50%.

Conclusion

Intensive care nurses see various triggers, with interprofessional collaboration and the patient's prognosis playing a major role. The questionnaire can be used for further surveys, e.g. interprofessional triggers could be developed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-024-04969-1.

Keywords: Trigger factors, Palliative care, Intensive care, Intensive care nurses, Interprofessional care, Interdisciplinary care

Background

Intensive care units (ICU) are places of surviving in which patients in crisis situations are stabilised to such extent that discharge can be aimed for and the possibility of recovery exists [1–3]. It is often claimed that a reduction in quality of life is accepted in return. However, attempts are made to include aspects of quality of life in therapy goals and treatment planning. Patients’ values are also enquired about and should be taken into account [4].

Despite the efforts of intensive care teams, critically ill people who can no longer be cured lie in intensive care units. In addition 20% of patients die in an ICU or shortly after admission to an ICU [1, 2]. ICU patients and their relatives can therefore suffer from distressing symptoms [1, 2]. Therefore palliative care needs may arise [2]. Appropriate pain and symptom management, as well as consistent communication and decision-making, can be a challenge in patients with life-threatening illness [5]. Recommendations support the early integration of palliative care structures within the ICU setting [6–8]. Integration of such structures is possible at various levels. Primary palliative care can be provided by the ICU teams themselves without specialised palliative care (sPC) teams by addressing all palliative needs of patients and relatives. Another option would be the consultative model, in which the specialised palliative care team addresses all palliative care needs. However, the mixed model is the most recommended. Here, ICU and sPC teams work together to fulfil the palliative needs of patients and relatives [9].

Palliative care teams focus on symptom relief, effective communication about treatment goals, alignment of treatment with patients’ preferences, family support and care planning [5]. Co-treatment by multiprofessional sPC teams therefore is an appropriate option for ICU patients and can also be offered in conjunction with life-prolonging treatments and especially in collaboration with ICU teams [10–12]. Timely integration of palliative care can complement counselling, treatment and support for relatives and patients, which can lead to improved quality of life and satisfaction for both [13]. The length of stay in ICU may be reduced and inappropriate therapies avoided [2, 5]. Communication between physicians and nurses can improve and lead to higher patient and care-taker satisfaction [13].

Despite the advantages of collaboration between intensive and palliative care, difficulties of identifying patients who benefit from such shared care persist. Various studies have investigated different incentives that should lead to involvement of palliative care, including treatment preferences and options, length of stay and conflicts [5, 14–17]. Such so-called triggers were either determined in expert panels or retrospectively collected using patient data.

In Germany, these triggers were supplemented in an expert panel and checked for acceptance among ICU physicians [18]. Table 1 describes examples of possible clinical situations to which potential triggers may apply and how patients can benefit from collaboration between ICU and sPC teams.

Table 1.

Examples for clinical situations with possible triggers and benefits

| Clinical situation | Possible trigger | Possible benefit from specialized palliative care (sPC) |

|---|---|---|

| Relatives are informed about a possible limitation of the patient's lifetime. They perceive that the ICU team is putting a lot of effort into symptom control. Nevertheless, they would like an integration of sPC (e.g. due to own burden) | Relatives’ sPC request | The sPC team can support the ICU team in caring for relatives. Together they can provide the best possible care for those affected. Thus relatives experience support and relief |

| The patient suffers from complex symptoms | High symptom burden | The sPC team can use its expertise and perspective to assess symptom burden and to recommend strategies to alleviate it. Together with the ICU team and their expertise, the best possible symptom control can be achieved |

| The patient has an inoperable, advanced tumor. He receives maximum intensive care therapy over a longer period of time, which is continued and not adapted to any new therapy goals that may need to be achieved | Unresectable malignancy | In the case of a serious life-limiting underlying disease, sPC can be consulted regardless of the indication for intensive care. The ICU and sPC team can work together to assess the situation and realistic therapy goals. Consequently, they plan and implement treatment and care for the patient's comfort |

As nurses play a major role in the care of ICU patients, they should be involved in decision-making [10] as well as in the development of triggers [15].

The aim of this study was to identify triggers that, from the perspective of German ICU nurses, should prompt the involvement of sPC for an ICU patient, and to evaluate the acceptance of these triggers.

Methods

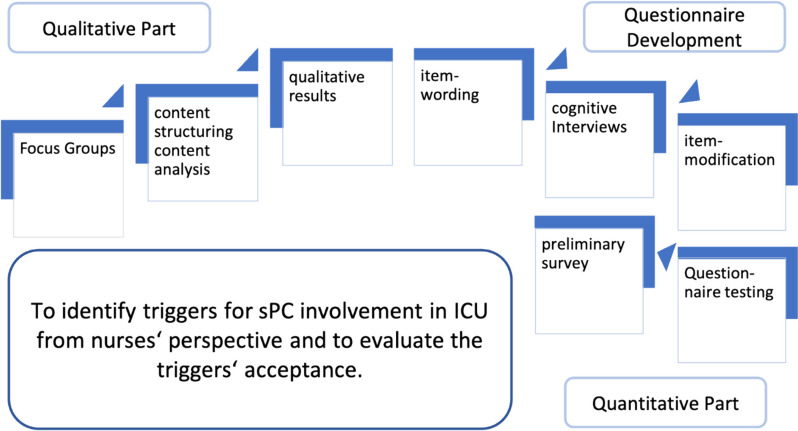

In order to achieve the study objective, focus groups were conducted to identify triggers. These were then formulated into items for a questionnaire. The questionnaire was tested and an initial analysis of the acceptance of the triggers was carried out. Figure 1 illustrates the detailed study design and objectives.

Fig. 1.

Conceptional model and study aims. sPC specialised palliative care, ICU intensive care unit

Focus groups

Semi-structured focus groups were conducted with ICU nurses to obtain their perspectives. Potential participants were informed about the study by gatekeepers, in this case management staff, and asked to participate. Volunteers participated in the sense of a convenience sample. Nurses with at least 1 year of professional experience and current work in ICU who had contact with sPC were included. The interview guide was developed by the author team based on the research question about possible triggers for sPC involvement, including sub-questions and targeted follow-up questions. The focus groups were moderated by MS, a nurse and research assistant (Dr. PH) with experience in qualitative research and palliative and neonatal intensive care. This experience and her interest in the study—to deeper understand and strengthen the nurses' perspective—was disclosed to the participants in advance. Focus groups were recorded as audio files and transcribed according to “simple rules” [19]. No field notes were made.

Data were analysed in seven steps (initiating textwork–main categories–coding–compile passages–subcodes–coding–analysis) using the “content-structuring content analysis” according to Kuckartz [20]. Data coding was primarily done by MS using MAXQDA (Version 12, Verbi GmbH). The authors MN and JidS participated in the analysis and coding. This took place in close consultation.

Questionnaire development

The qualitative analysis took place independently of the following step of item formulation. Nevertheless, it was the basis for developing a questionnaire to assess the acceptance of the identified triggers. These were worded into items considering the ten principles of question framing [21]. An intention was to correspond to as closely as possible to the data material. Not only the main categories and subcategories were relevant, but also the data material in the sense of the transcripts of the focus groups in order to include the content mentioned. The formulated items were repeatedly discussed in a multi-stage process within the research group with regard to appropriateness and understanding. Participants were asked for agreement on a five-point Likert scale.

In order to optimise comprehensibility, cognitive interviews were conducted to learn more about the cognitive processes that take place when answering the questions. Of interests here is how the interviewees interpret and understand terms or questions, how they recall information and events from mind, how they make decisions about how to answer and how they allocate their answers to the formal answer categories. In the present study, the techniques of inquiring for understanding, paraphrasing and thinking aloud were used [22]. When inquiring about understanding, participants are asked to describe their understanding of certain terms or the entire item. Paraphrasing asks participants to repeat an item in their own words without remembering the literal text. Thinking aloud is intended to capture the mental processes that take place when answering the items. To do this, the item is read out loud and the participants are asked to speak out their thoughts on answering. The interviews were recorded as audio files and then also transcribed according to “simple rules” [19]. When MS conducted the interviews, care was taken not to use any non-verbal amplifiers.

In this way, almost all items were assessed for understanding. Only items that seemed evident were left out, such as the question whether the patients’ age could be a trigger for involving sPC. Test persons were nurses with intensive and palliative care experience.

Questionnaire testing with preliminary survey

Following the cognitive interview screening, a pilot was conducted in which the questionnaire was given to a small sample (n = 30) of the envisaged target group. For recruitment, head staff from three intensive care units were approached, who distributed the questionnaires to potential participants. The sample was asked to complete the questionnaire, and invited to critically comment on each item as well as at the end of the questionnaire. In addition, the time needed to complete the questionnaire was measured.

The analysis of the pilot also indicated a first tendency of the acceptance of triggers. For this purpose, as in a former study on the acceptance of triggers for sPC involvement among ICU physicians, all triggers that received at least 50% agreement were defined as accepted [18].

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University Duesseldorf, Germany (Study ID: 6114R) and conform to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were all at least 18 years old.

Results

Focus groups

Between February 2018 and July 2019, six focus groups were conducted at four German university hospitals, involving a total of 28 ICU nurses. They represented the fields of surgery, neurosurgery and internal medicine. Three participants cancelled their participation due to illness. The duration of the focus groups, which took place in separate rooms in the work environment, was 45–90 min.

After four focus groups, there seemed to be a saturation, which became more apparent after the fifth. To strengthen this assumption, a sixth focus group took place which yielded no relevant additional information.

Since all the triggers mentioned were to be included in the evaluation and thus in the development of the questionnaire, no member check, in which the analysis is returned to the participants for review, took place.

All participants were able to report experiences of cooperation with sPC. They expressed seeing the patients’ benefit from the support, but they would like the teams to be involved earlier and more regularly. The most important element is that sPC do something good for the patients and that nurses themselves can benefit from the expertise.

Just do something good for the person for an hour (FG 1)

Simply use the expertise they bring with them (FG 6)

Overall, four main categories “prognosis, interprofessional cooperation, relatives, patients” could be formed out of the data with three to 15 subcategories each. Table 2 shows the main categories of the focus groups with examples of the related quotes and examples of the answers to the open question on piloting the questionnaire.

Table 2.

Quotes from the main focus group categories and the open question in the pilot questionnaire

| Main categories focus groups | Quote examples |

|---|---|

| Prognosis | “where it is no longer ethically tenable” (FG 3) |

| “But he cannot die yet, because we simply interfere with our devices. What do we refrain from?” (FG4) | |

| “so above all […] the AML patients, ALL patients” (FG3) | |

| “for each long-term patient […] a weekly case discussion, preferably after the first week” (FG1) | |

| Interprofessional cooperation | “Many cases we consider already a palliative care case, but the physicians do not. They continue to deliver life-sustaining treatment until the overall condition of the patients deteriorates so drastically that nothing more can be done for them, and only then they die” (FG 6) |

| “There is no open discussion with the relatives. When you talk to them, they don't realise that this is the condition in which the patient will stay.” (FG3) | |

| Relatives | “Very serious complex illness situations where the relatives have to be supported […] where someone should also be there for the relatives.” (FG1) |

| “The medical treatment is exhausted, but the relatives see it differently […] Situation where relatives dictate the treatment and physicians allow it” (FG4) | |

| Patients | “How do you take away the shortness of breath, mental problems […] if you then also ask for a specialised palliative care consultation, the psychologist will also come.” (FG 6) |

| “actually mainly for very young patients”(FG 3) | |

| Open question questionnaire | “THIS absolutely has to happen and the specialised palliative care team could mediate” (on the item Involving relatives in discussions about the further procedure) |

| “Sometimes very good discussions are held, sometimes encouragement is still given where it is hopeless” |

Prognosis

In this category, factors are named that have an influence on or are associated with a certain course and thus the prognosis. Consequently, it is about the ethical assessment of the patient's situation and the treatments undertaken, in which the ICU nurses ask for support from sPC.

SPC can support in raising comprehensive awareness of the patient's situation and enable a natural passing in the highly technical field by looking at the overall situation.

Severe pre-existing conditions such as certain oncological diseases, complications, the need for resuscitation or ventilation and length of stay in the ICU can have an influence on the prognosis and were therefore seen as triggers for the involvement of sPC.

Interprofessional cooperation

The participants described a potential for conflicts between ICU nurses and physicians at various points of care when nurses would like to have support from sPC.

ICU nurses prefer to be more involved in decisions, especially in order not to maintain life-sustaining treatment unnecessarily. In addition, they see different levels of knowledge and understanding about the work and tasks of sPC which can intensify a conflict.

Conflicts can also arise in terms of communication. The participants see that ICU physicians do not always communicate openly with relatives as well as with themselves, the nurses. This can make decision-making more difficult and increase burdens.

Relatives

Factors that can trigger sPC consultation can also be found in relatives. For example, they may be so burdened by the situation that they need additional support. This is particularly relevant in decision-making, where relatives may feel a sense of responsibility. SPC can also provide support in involving relatives in care processes.

Relatives` wish for palliative care counts also as a trigger for the participants. Conversely, a relative`s forceful request for ongoing life-sustaining treatment in a clear palliative situation also represents a trigger.

Patients

Personal characteristics of the patients can also be reasons for involving sPC.

Concerning age, sPC is more likely to be involved in the case of young patients.

Questionnaire development

The triggers developed from the qualitative results led to 32 questionnaire items. These related to the individual patients` situation, the disease or the overall situation between the patient and the treatment team. The items were supplemented by an open free-text field in which further, unnamed triggers could be specified, as well as nine questions on demographics.

Cognitive interviews

In the cognitive interviews, 6 items were not tested because they were clearly understandable, such as the question about the age of the patient or the length of stay in the ICU.

In order to test the 26 other items, five cognitive interviews were conducted with one participant each, all of whom had experience in both intensive and palliative care. None of them had been part of the previous focus groups. They were asked about five or six items each in 60–90 min interviews.

The evaluation showed that four items should be modified. For example, the term “natural death” had to be defined more precisely. The remaining 22 items were understood as they were meant. The items’ interpretation by the participants was consistent to what the focus groups had described.

Questionnaire pilot with preliminary survey

The questionnaire used for the pilot consisted of 32 triggers to be tested, one open question for triggers not mentioned, nine questions on demographics and three additional questions at the end that can give statements on the piloting of the questionnaire, i.e., a total of 45 questions.

Possible participation was openly addressed in the participating ICU teams, as was the voluntariness of participation. Due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the associated burdens as well as a general shortage of staff in nursing teams, the response rate was 76.7% of the 30 questionnaires distributed. The study team consulted with each other and decided that the number of questionnaires was sufficient for an initial survey and thus for the tendency of the results. Data on the participants are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participants in the questionnaire pilot n = 23 (in %) (*intensive care unit)

| Gender | Female 14 (60.9%) | Male 9 (39.1%) | Divers 0 |

| Department | Internal medicine 12 (52.2%) | Surgery 11 (47.8%) | |

| Professional experience | 1–5 years 6 (26.1%) | > 5 years 17 (73.9%) | |

| Age | 20–29 years 8 (34.8%) | 30–39 years 9 (39.1%) | 40–59 years 6 (26.1%) |

| ICU*experience | 1–5 years 8 (34.8%) | > 5 years 15 (65.2%) | |

| Intensive care and anaesthesia training | Yes 15 (65.2%) | No 8 (34.8%) |

On average, completion of the questionnaire took 27 min. Twelve participants used the free text fields under the items (Table 2). The free comments related mainly to a reason for accepting or rejecting the particular trigger.

Some free text statements were similar to the statements in the focus groups, describing own experiences with the sPC teams.

One item which refers to the likelihood to achieve treatment goals was adjusted on the basis of the free text comments because the term “treatment goal” was perceived as ambiguous.

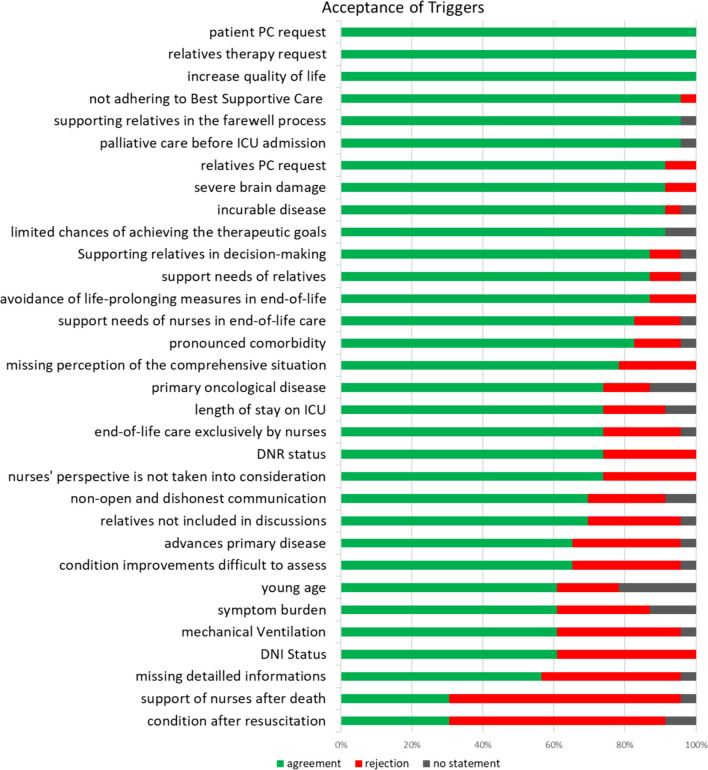

The answers “fully agree” and “rather agree” were evaluated as acceptance of the respective trigger, and “rather disagree” and “strongly disagree” as rejection. “No statement” was also collected and indicated, but was not included in acceptance or rejection. With at least 50% agreement, 30 of the 32 triggers were accepted and two were rejected. Figure 2 illustrates the results of the individual items.

Fig. 2.

Acceptance of the triggers in the pilot. ICU intensive care unit, PC palliative care, DNR do not resuscitate, DNI no ICU transfer

For further differentiation, the participants were able to provide detailed information on time and age for the questions on age, duration of ventilation and length of stay in the ICU. The median duration of ventilation was 21 days, the median duration of stay in the ICU was 14 days and the median age was < 50 years.

A further more detailed description was possible for the item symptom burden in order to name symptoms for which the participants expect a benefit from involving a sPC team. Anxiety, pain and depression were named most frequently.

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify possible triggers for the involvement of sPC for ICU patients and their relatives from the perspective of ICU nurses. The identification of patients who benefit most from sPC involvement is important both to address the patients individual needs and to use sPC as a limited resource efficiently [9, 23]. The triggers identified in the present study relate to the individual patient situation and the support needs of patients, relatives and the intensive care nurses.

The focus groups show a conflict between physicians and nurses. Intensive care nurses feel not sufficiently involved in treatment decisions, decisions about further procedures and discussions with the patient, as mentioned in the focus groups, which leads to frustration [3]. They feel that they would involve sPC more often if they were more involved in decisions or had the opportunity to involve sPC themselves. However, physicians still want to initiate sPC involvement themselves [16].

ICU nurses ask for support from sPC in recognising and adhering to treatment limitations and in including their perceptions in decision-making processes. Especially when the prognosis is unclear, the challenge often is to recognize timely when maximum therapeutic measures represent a burdensome overtreatment that is out of proportion to the possible outcome [4]. A good ethical climate in the ICU and nursing involvement at the end of life can reduce excessive care [24]. The rejection of the trigger “support of nurses after death” is difficult to interpret. In the literature, relatives describe the situation very differently, sometimes they continue to receive support, sometimes they have the feeling that care ends quickly after death [25]. Perhaps more education is needed here about the fact that palliative care does not have to end with the death of the patient, but that it can initially accompany the relatives. ICU and sPC nurses can then provide this support together. Perhaps ICU nurses do not see any need for themselves here because they have sufficient expertise in this area and do not have any need for further support. Further consideration is required here.

Pre-existing diseases, whether related to the acute crisis or not, can have an influence on prognosis. These can include oncological diseases or brain damage like mentioned in the focus groups. Other advanced conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure may also worsen prognosis [26, 27]. Such underlying diseases may facilitate the involvement of sPC. Here the tasks of palliative care lie in recovery and maintenance of quality of life [5, 28].

The importance of relatives in the decision to involve the sPC team is made clear in the study by the fact that they were often mentioned in the focus groups and also agreed with the items concerning them in the questionnaire. They should therefore be given prominence and taken into account not only in decision-making processes, but also in the provision of care.

They experience an exceptional situation, which can lead to increased stress and thus to an increased need for support [3]. SPC can offer additional support here, also because they can offer psycho(onco)logical support due to the multiprofessional structure. This can increase the quality of care [15].

ICU patients are often unable to communicate and thus express their wishes. As a result, relatives oftentimes communicate the patient's wishes on the basis of advance directives or presumed patient will and, if they are legal representatives, make decisions on their behalf. Therefore, they have to be adequately informed about the current condition, therapeutic options, their consequences and short- and long-term prognosis [29].

It may be helpful for them to be able to identify triggers for sPC involvement through discussion or involvement in decision-making and care. These may even be co-developed or asked for their perspective during the development. There is a need for further research.

The length of stay in an intensive care unit is mentioned as a trigger both in this study and in the literature. A stay of more than 7 days [15] or 1 month [14] is cited as a reason for sPC involvement. SPC can provide support in clarifying the prognosis, but can also be a constant reference person for relatives with frequently changing intensive care staff [30].

In the case of age, the literature tends to see old age as a trigger [5, 17]. The reason why young age is mentioned more in the focus groups may be due to the additional emotional burden felt by the caregivers.

In this study, triggers were analysed from the perspective of nurses. As nurses and physicians work together in the ICU, acceptance of the triggers by both professional groups is important.

The triggers in this study can only be partially compared with those from the literature due to the different identification. However, eight triggers—patients’ request, relatives' request, incurable disease, (severe) brain damage, length of stay in ICU, primary oncological disease, (high) symptom burden, mechanical ventilation—were tested for acceptance among German ICU physicians [18] and were also named by nursing staff in the present study. The four in italics are accepted by both professional groups and can therefore form the basis for interprofessional decisions or further studies on multiprofessional triggers.

Limitations

It cannot be excluded that for the focus groups mainly nurses volunteered who felt that the involvement of the sPC was particularly important, and therefore had a greater interest in participating. This may mean that other perspectives are underrepresented in our sample.

Much of what is said in the focus groups can also be part of an ethics consultation [31]. Here it would be necessary to differentiate whether sPC is necessary or whether an ethic consultation can support.

The pilot was planned with 30 questionnaires in order to test the questionnaire, but also to conduct a first evaluation. Due to the tense situation, also caused by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which led to enormous stress for the carers, this number was not reached. The response rate of 23 questionnaires allows no more than an explorative analysis of pure agreement versus rejection.

The participants in this study were ICU nurses. The results show that relatives are highly relevant. They and their perspective should therefore be the target group of future studies on this topic.

Conclusion

The nurses interviewed in the focus groups see a clear benefit for those affected in the shared care provided by sPC. In the perspective of ICU nurses, the relevant functions of sPC can be both advisory and (co-)treating.

With the formulated triggers, they can now bring this into decision-making processes. A shared exchange based on the triggers can also support the conflict described.

The piloted questionnaire can now be used to test the triggers for acceptance in a larger cohort. The initial evaluation confirms the triggers brought forward in the focus groups. A cross-professional survey is also possible to develop multi-professional triggers.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who openly reported on their daily work and without whom the study would not have been possible.

Abbreviations

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- sPC

Specialised palliative care

- Dr. PH

Doctoral degree in public health

Author contributions

MS, MN, JS, AI, JidS developed the study. MS, MN, JidS, AI conducted and primarily evaluated the study. AI, JS, YNB, MMD, TT, SM provided support and advice. All authors contributed to the manuscript and agreed with the submission.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the extend but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received a positive ethics approval from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Germany (Study-ID: 6114R). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, which were all older than 18 years old.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ. Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of interventions. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:219–235. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemens KE, Klaschik E. Integration palliativmedizinischer Prinzipien in die Behandlung von Intensivpatienten: Vom "shared decision making" und der Begleitung von Angehörigen. Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2009;44:88–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michalsen A, Neitzke G, Dutzmann J, Rogge A, Seidlein A-H, Jöbges S, et al. Überversorgung in der Intensivmedizin: erkennen, benennen, vermeiden: Positionspapier der Sektion Ethik der DIVI und der Sektion Ethik der DGIIN. [Overtreatment in intensive care medicine-recognition, designation, and avoidance: Position paper of the Ethics Section of the DIVI and the Ethics section of the DGIIN] Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00063-021-00794-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michels G, John S, Janssens U, Raake P, Schütt KA, Bauersachs J, et al. Palliativmedizinische Aspekte in der klinischen Akut- und Notfallmedizin sowie Intensivmedizin: Konsensuspapier der DGIIN, DGK, DGP, DGHO, DGfN, DGNI, DGG, DGAI, DGINA und DG Palliativmedizin. [Palliative aspects in clinical acute and emergency medicine as well as intensive care medicine: Consensus paper of the DGIIN, DGK, DGP, DGHO, DGfN, DGNI, DGG, DGAI, DGINA and DG Palliativmedizin] Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2023;118:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s00063-023-01016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michels G, Schallenburger M, Neukirchen M. Recommendations on palliative care aspects in intensive care medicine. Crit Care. 2023;27:355. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04622-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neukirchen M, Metaxa V, Schaefer MS. Palliative care in intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:1538–1540. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07260-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JR, Higginson IJ, White DB. Integrating palliative care into the ICU: a lasting and developing legacy. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48:939–942. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards JD, Voigt LP, Nelson JE. Ten key points about ICU palliative care. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:83–85. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4481-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frontera JA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE, Campbell M, Gabriel M, Mosenthal AC, et al. Integrating palliative care into the care of neurocritically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1964–1977. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mentzelopoulos SD, Chen S, Nates JL, Kruser JM, Hartog C, Michalsen A, et al. Derivation and performance of an end-of-life practice score aimed at interpreting worldwide treatment-limiting decisions in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2022;26:106. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03971-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CT, Brasel KJ. Developing guidelines that identify patients who would benefit from palliative care services in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:946–950. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181968f68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson JE, Curtis JR, Mulkerin C, Campbell M, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, et al. Choosing and using screening criteria for palliative care consultation in the ICU: a report from the improving palliative care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Advisory Board. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2318–2327. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf12c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysham NG, Hua M, Hough CL, Gundel S, Docherty SL, Jones DM, et al. Improving ICU-based palliative care delivery: a multicenter, multidisciplinary survey of critical care clinician attitudes and beliefs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e372–e378. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the need for palliative care consultation across united states intensive care units using a trigger-based model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:428–436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adler K, Schlieper D, Kindgen-Milles D, Meier S, Schallenburger M, Sellmann T, et al. Will your patient benefit from palliative care? A multicenter exploratory survey about the acceptance of trigger factors for palliative care consultations among ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:125–127. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dresing T, Pehl T. Praxisbuch transkription: regelsysteme, software und praktische anleitungen für qualitative forscherinnen. 2. Marburg: Eigenverlag; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuckartz U. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, praxis, computerunterstützung. 4. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porst R. Praxis der umfrageforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prüfer P, Rexroth M. Kognitive interviews. Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downar J, Hua M, Wunsch H. Palliative care in the intensive care unit: past, present, and future. Crit Care Clin. 2023;39:529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2023.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benoit DD, Jensen HI, Malmgren J, Metaxa V, Reyners AK, Darmon M, et al. Outcome in patients perceived as receiving excessive care across different ethical climates: a prospective study in 68 intensive care units in Europe and the USA. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1039–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, Lustbader DR, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C, et al. Integrating palliative care in the ICU. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13:89–94. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318203d9ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao Y, Xing Z, Long H, Huang Y, Zeng P, Janssens J-P, Guo Y. Predictors of mortality in COPD exacerbation cases presenting to the respiratory intensive care unit. Respir Res. 2021;22:77. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01657-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai Y, Qin S, Pan H, Chen T, Bian D. Impacts of comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure on prognosis of critically ill patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:2707–2714. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S275573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berendt J, Ostgathe C, Simon ST, Tewes M, Schlieper D, Schallenburger M, et al. Zusammenarbeit von Intensivmedizin und Palliativmedizin: Eine Bestandsaufnahme an den deutschen onkologischen Spitzenzentren. [Cooperation between intensive care and palliative care: The status quo in German Comprehensive Cancer Centers] Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00063-020-00712-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox CE, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray AL, et al. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2888–2894. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab86ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murali KP, Fonseca LD, Blinderman CD, White DB, Hua M. Clinicians' views on the use of triggers for specialist palliative care in the ICU: a qualitative secondary analysis. J Crit Care. 2022;71:154054. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2022.154054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell JAH, Salis M, Tong E, Nekolaichuk E, Barned C, Bianchi A, et al. Clinical ethics consultations: a scoping review of reported outcomes. BMC Med Ethics. 2022;23:99. doi: 10.1186/s12910-022-00832-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the extend but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.