The World Health Organisation’s definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” clearly relates social and mental wellbeing to physical health.1 For many years, however, attempts to improve health in the developing world concentrated on physical illness—mental health was relegated to the bottom of the list of priorities.2 Only recently has it begun to appear at the forefront of international public health.3

Summary points

Deliberate self harm is common in the developing world

Self poisoning with agricultural pesticides or natural poisons such as oleander seeds is an important cause of mortality in many rural areas

Case fatality rates of pesticides such as paraquat and organophosphates may exceed 60%

Medical management of acute self poisoning is currently poor—better management protocols would reduce mortality

Research to improve management and find ways of reducing deliberate self harm is urgently required

Self poisoning in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has a high incidence of suicide—at least 40 suicides per 100 000 population each year compared with 8 per 100 000 in the United Kingdom.4,5 As part of a collaboration between the universities of Colombo and Oxford, we have been studying new treatments for self poisoning in Anuradhapura General Hospital, a secondary referral centre for 900 000 people living in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka. Our work there has allowed us to observe at first hand the tragic consequences of these deaths for the families and the community.

During 1995 and 1996, 2559 adults (age range 12-73 years; 1443 men and 1116 women) were admitted to the hospital with acute poisoning, almost all as a result of deliberate self harm. Altogether 325 (12.7%) died in the hospital—246 men and 79 women (17.0% and 7.1% of admissions, respectively). The poisons used were pesticides, yellow oleander (Thevetia peruviana) seeds, and medicinal or domestic agents. Organophosphate and carbamate pesticides caused 914 admissions to hospital and 199 (21.8%) deaths, and oleander poisoning accounted for 798 admissions to hospital and 33 (4.1%) deaths over a 21 month period.

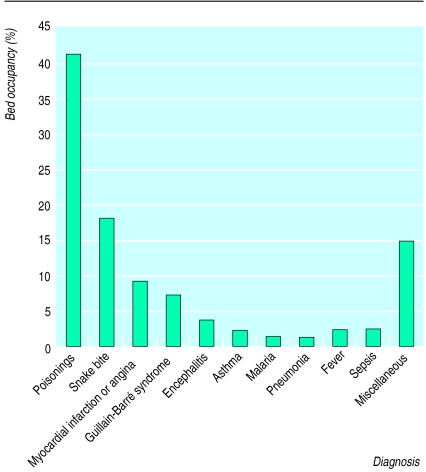

The number of patients admitted to hospital with acute poisoning in this region of Sri Lanka has increased enormously over the past five years, causing great stress to the already overstretched medical services. For example, in 1995 and 1996, patients with organophosphate poisoning occupied 41% of the hospital’s medical intensive care beds (fig 1), preventing other ill patients from being admitted to the unit.

Figure 1.

Bed occupancy in relation to diagnosis in the medical intensive care unit of Anuradhapura General Hospital, Sri Lanka, 1995-6

Deliberate self harm or attempted suicide?

Many people admitted for deliberate self poisoning were young: about two thirds were aged under 30. Few expressed a desire to die but, unfortunately, deaths are relatively common among the young. Sixty per cent of deaths in female patients occurred in those aged less than 25 years. For most of the youngsters, self poisoning seems to be the preferred method of dealing with difficult situations. Examples include a 16 year old girl who died after eating oleander seeds because her mother said she could not watch television; a 13 year old boy who drank organophosphates after his mother scolded him, and who spent three weeks in intensive care being ventilated; and a 14 year old boy who presented in complete heart block after eating oleander seeds because his pet mynah bird had died.

The children are learning from people around them—they are surrounded by people who have previously attempted suicide. In interviews with 85 patients on the general medical wards, more than 90% stated that they knew someone who had harmed themselves, and 90% knew someone who had killed themselves. If knowing someone who has committed suicide is a risk factor for deliberate self harm, whole communities in Sri Lanka are at very high risk.6

The reasons for the epidemic are unclear. Sociologists have suggested that the young have few support systems and are unable to cope with societal and cultural demands.7,8 Frustrations felt by Sri Lanka’s highly educated youth in the face of war, poverty, and the lack of opportunity at home and abroad are also likely to be exacerbating factors.9

High death rates

The case fatality rate in Sri Lanka is extremely high. Altogether 12.7% of patients admitted to Anuradhapura Hospital after self poisoning die, compared with 1-2% in the United Kingdom. The rate in men who have drunk organophosphate poisons reaches 60% during some months. The reasons for this high mortality probably include the toxic nature of the substances involved, the lack of antidotes, the long distances between hospitals, and overstretched medical staff. Acute pesticide poisoning does not occur just in Sri Lanka—it is a major problem throughout the developing world, with a worldwide incidence of 3 million cases and 220 000 deaths each year.10

We believe that reducing the number of suicides in the developing world should become an international public health priority. Our experience in Sri Lanka suggests that research to improve medical management of acute poisoning and to reduce the incidence of deliberate self harm will be important ways of achieving this.

Improving management

Research is urgently required. Organophosphates produce respiratory failure and peripheral neuropathies; paraquat results in multiorgan failure or a drawn out death from lung fibrosis. Cardiotoxicity induced by yellow oleander can progress to ventricular fibrillation that resists shock from a direct current, and the status epilepticus induced by organochlorine can be managed only in major hospitals with facilities for mechanical ventilation.11

Protocols need to be developed for better management of these poisonings, particularly for use in rural units where patients first come into contact with the health services.12 At present, many patients die before they can be transferred to specialised hospitals. The available treatments also need to be subjected to rigorous trials. We still do not know, for example, whether pralidoxime is effective in organophosphate poisoning or whether activated charcoal improves the outcome.13,14

Preventing self harm

One way of reducing deliberate self harm would be to limit access to poisons.15 However, in Sri Lanka, most cases involve pesticides or yellow oleander seeds, and reducing access to these agents will be difficult. Since pesticides are the most lethal, it will be important to limit their availability (fig 2). Unfortunately, the rural farmer will continue to need ready access to pesticides since they are an important part of the developing world’s strategy for increasing its food production.16 Locking pesticides away safely (fig 2) is difficult in rural areas where farmers live in huts without bed, furniture, or cupboards. While it may be possible to ban the more toxic pesticides and replace them with safer ones, safer pesticides are expensive and therefore unaffordable in the developing world. Furthermore, banning particular pesticides has often led to the adoption of other, equally dangerous ones.

Figure 2.

“Lock up your pesticides.” A Sinhalese poster suggesting four reasons why someone might decide to take pesticides and telling people to lock their pesticides away safely

It seems much more important to strike at the core of the problem—the practice of deliberate self harm. It will be a major challenge to set up programmes that reduce its incidence. However, it is here that the greatest potential exists. Although untested, widespread education in schools to help children deal with life’s stresses and to get help, plus increased availability of counselling, may be the way forward.17

Conclusions

Deliberate self poisoning is a major problem in the developing world, where it is the cause of many deaths, particularly among young people. In suggesting ways of preventing deliberate self harm in the developing world we must be realistic, particularly since its incidence is still increasing in the West—2700 people are referred to hospital for self poisoning each week in the United Kingdom alone.18 It is likely to be even more difficult for the developing world, with its limited resources, to address this problem effectively. However, we think that the time has come to acknowledge the seriousness of the situation as a first step towards preventing this massive unnecessary loss of life.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors David Warrell and Kamini Mendis and the members of the Ox-Col Collaboration for support during ME’s time in Sri Lanka; Ariaranee Ariaratnam and Zeena for interviewing the patients, and Tony Hope, Varuni Ganepola, and Robert Mahler for their critical comments on the manuscript. We also thank Dr R Perera, Director General of Health Services, Sri Lanka, for comments on this manuscript and strong support for our work.

Footnotes

Funding: ME’s stay in Sri Lanka was supported by Therapeutic Antibodies Ltd, London.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Basic documents (forty-first edition) including amendments adopted up to 31 October 1996. Geneva: WHO; 1996. Constitution of the World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. World health report 1995. Geneva: WHO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, Kleinman A. Mental health: problems, priorities, and responses in low-income countries. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health. Annual health bulletin, Sri Lanka, 1995. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ministry of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. 1994 world health statistics annual. Geneva: WHO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawton K, Catalan J. Attempted suicide. A practical guide to its nature and management. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Silva P, editor. Suicide in Sri Lanka. Kandy: Institute of Fundamental Studies; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasturiaratchi ND, de Silva HJ, Ellawala NS, Senaratne DC, Premawardene AP, Seneviratne SL. A study of suicide in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Sumithrayo; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osmani SR. Is there a conflict between growth and welfarism? The significance of the Sri Lanka debate. Dev Change. 1994;25:387–421. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeyaratnam J. Acute pesticide poisoning: a major global health problem. World Health Stat Q. 1990;43:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sood AK, Yadav SP, Sood S. Endosulphan poisoning presenting as status epilepticus. Indian J Med Sci. 1994;48:68–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddleston M. Deliberate self-poisoning in Sri Lanka—improved medical management through clinical research. Ceylon Coll Physicians J (in press).

- 13.De Silva HJ, Wijewickrema R, Senanayake N. Does pralidoxime affect outcome of management in acute organophosphate poisoning? Lancet. 1992;339:1136–1138. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90733-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S, Batra YK, Singh SM, Wig N, Sharma BK. Is atropine alone sufficient in acute severe organophosphate poisoning? Experience of a north west Indian hospital. Int J Clin Pharmacol Therapeut. 1995;33:628–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Intervention Options. Investing in health research and development. Geneva: WHO; 1996. (Document TDR/Gen/96.1.) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Report of the world food summit. Rome: FAO; 1996. Commitment 3. Rome declaration on world food security and world food summit plan of action. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellawala NS. Strategies of suicide prevention. In: De Silva P, editor. Suicide in Sri Lanka. Kandy: Institute of Fundamental Studies; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A. Trends in deliberate self harm in Oxford, 1985-1995: implications for clinical services and the prevention of suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:556–560. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]