Abstract

FICZ (6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole) is a potent aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has a poorly understood function in the regulation of inflammation. In this study, we investigated the effect of aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by FICZ in a murine model of autoimmune hepatitis induced by concanavalin A. High-throughput sequencing techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing and assay for transposase accessible chromatin sequencing were used to explore the mechanisms through which FICZ induces its effects. FICZ treatment attenuated concanavalin A–induced hepatitis, evidenced by decreased T-cell infiltration, decreased circulating alanine transaminase levels, and suppression of proinflammatory cytokines. Concanavalin A revealed an increase in natural killer T cells, T cells, and mature B cells upon concanavalin A injection while FICZ treatment reversed the presence of these subsets. Surprisingly, concanavalin A depleted a subset of CD55+ B cells, while FICZ partially protected this subset. The immune cells showed significant dysregulation in the gene expression profiles, including diverse expression of migratory markers such as CCL4, CCL5, and CXCL2 and critical regulatory markers such as Junb. Assay for transposase accessible chromatin sequencing showed more accessible chromatin in the CD3e promoter in the concanavalin A–only group as compared to the naive and concanavalin A–exposed, FICZ-treated group. While there was overall more accessible chromatin of the Adgre1 (F4/80) promoter in the FICZ-treated group, we observed less open chromatin in the Itgam (CD11b) promoter in Kupffer cells, supporting the ability of FICZ to reduce the infiltration of proinflammatory cytokine producing CD11b+ Kupffer cells. Taken together, these data demonstrate that aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by FICZ suppresses liver injury through the limitation of CD3+ T-cell activation and CD11b+ Kupffer cell infiltration.

Keywords: aryl hydrocarbon receptor, autoimmune hepatitis, FICZ, inflammation, liver injury, scATAC-seq, scRNA-seq

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by FICZ suppresses liver injury induced by concanavalin through the limitation of CD3+ T-cell activation and natural killer T-cell and CD11b+ Kupffer cell infiltration.

1. Introduction

In women under 65 yr of age, autoimmune diseases are among the leading causes of death in the United States.1 Although the liver was one of the first organs recognized for autoimmunity, there still exists a difficulty in correctly diagnosing autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and other liver autoimmune diseases.2 It is for these reasons that the relatively low prevalence of AIH is likely underestimated.3 Despite this, AIH accounts for nearly 6% of liver transplants in the United States, and the recurrence rate after transplantation ranges from 17% to 41%.4 AIH is generally defined as a T-cell–mediated response toward liver antigens characterized by the presence of circulating autoantibodies and high concentrations of serum globulins and aminotransferases.5,6 While current treatment with immunosuppressants can improve survival, there are several issues associated with this regimen, and novel strategies are needed to improve the treatment approach.7 To achieve this, more information is needed regarding the changes that occur in immune cells during the progression of an autoimmune response.

The concanavalin A (ConA) model of liver injury mimics AIH in humans in that the damage is induced by immune cells and the symptoms imitate autoimmunity.8,9 ConA is a plant lectin whose exposure results in immune cell activation, cytokine secretion, and serological and histological features, all of which are consistent with human AIH.10,11 It is well established that many immune cell subsets are involved during this model, so it is imperative to explore how each subset responds to ConA exposure and subsequent aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) activation.

The ligand-dependent transcription factor known as AhR has been implicated in not only xenobiotic metabolism but also immunity.11–15 Studies have shown success in using AhR ligands to modulate the immune response in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.11,16–20 The endogenous ligand 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ) exerts contrasting effects, possibly due to its rapid metabolism, including induction of proinflammatory T helper 17 cells (Th17) in some models and induction of anti-inflammatory cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) or subsets of macrophages in others.21 For these reasons, we sought to assess the mechanisms induced in liver immune cells upon activation of AhR with this ligand.

In the current study, we conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-cell assay for transposase accessible chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) on infiltrating liver mononuclear cells during ConA-induced liver injury to interrogate the immunological changes induced upon treatment with the AhR ligand FICZ. We found that FICZ improves the clinical parameters of ConA-induced liver injury, and in addition to reversing the presence of natural killer T (NKT) cells and T-cell subsets in the liver previously induced by ConA, molecular changes were also reversed. Further, more accessible chromatin was observed in Kupffer cell–associated genes, and flow cytometry showed that FICZ limited the infiltration of CD11b+ cytokine-producing Kupffer cells. We concluded that FICZ predominantly exerts effects on macrophages to attenuate ConA-induced liver injury.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

C57Bl/6 mice, 8–10 wk old, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA, USA) (JAX Stock # 000664). Mice were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC)-accredited, specific pathogen–free facility. Mice were randomized prior to treatments.

2.2. Reagents

The following reagents were used during the experiments: concanavalin A, FICZ, and β-mercaptoethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); Percoll from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Pittsburgh, PA, USA); mouse liver dissociation kit and red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany); RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and HEPES from VWR (West Chester, PA, USA); bovine albumin fraction V from ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, CA, USA); fluorophore-conjugated antibodies and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA); scRNA-seq and ATAC-seq kits from 10x Genomics (Pleasanton, CA, USA); Illumina NextSeq reagents from Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA); and penicillin–streptomycin by Gibco from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3. Induction of ConA-induced liver injury and FICZ treatment

ConA-induced liver injury was induced according to previously published protocols.22,23 In brief, mice were given a single dose via intravenous injection of 12.5 mg/kg body weight of ConA in PBS or vehicle (PBS). Mice were treated with 50 μg/kg FICZ or corn oil (vehicle) intraperitoneally 1 h later. Mice were euthanized by overdose isoflurane inhalation 24 h after ConA exposure. Protocols approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee were followed for all experiments.

2.4. Cell isolation

Liver mononuclear cells were isolated using the Miltenyi Biotec mouse liver dissociation kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Dissociation mix was prepared in C tubes and placed at 37 °C. Dissected liver tissue was placed in the C tubes and homogenized using the gentleMACS dissocator, under the m_liver_03 setting. Samples were rotated at 100 revolutions per minute (rpm), at 37 °C for 30 min. The tubes were placed back on the gentleMACS dissociator, and the cell suspension was filtered and then washed with 5 mL Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium. Samples were spun for 10 min at 25 °C and 300 × g, to generate a cell pellet. The supernatant was then discarded and the pellet resuspended in 6 mL staining buffer (PBS with 2% heat inactivated FBS and 1 mM EDTA). The reuspended cells were in Percoll to create a resulting 33% Percoll solution and then placed in the centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature (RT). After discarding the supernatant, cell pellets were resuspended in a 1-mL RBC lysis solution and incubated on ice for 5 min. Samples were then washed with staining solution. The resulting single-cell suspension was filtered and centrifuged for 7 min at 1,300 rpm at 4 °C. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 10 mL staining buffer and counted using the Bio-Rad TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Hercules, CA, USA).

2.5. Histology

Perfusion was performed on isoflurane-euthanized mice using 10 mL heparinized PBS preceding liver tissue dissection. Tissue fixation was performed by placing samples in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h, 70% ethanol for 24 h, and 1% PFA overnight. Fixed tissues were then embedded in paraffin by the university's instrumentation resource facility (IRF). The IRF continued to process tissues by sectioning tissue at 10 microns and placing on microscope slides before performing hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver sections under standard protocols. Using brightfield microcopy, samples were evaluated based on tissue injury and the presence of infiltrating leukocytes.

2.6. Analysis of alanine aminotransferase levels

Twenty-four hours after ConA injection, mice were euthanized, and blood was collected from the vena cava. Blood samples were centrifugated at 5,000 rpm for 10 min to separate and collect serum. Using the commercially available spectrophotometric assay kit (Pointe Scientific, Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada), the activity of the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was evaluated.22

2.7. Assessment of inflammatory profile

Culture supernatants were collected after 24 h from primary cultures of isolated liver mononuclear cells from various groups of mice and plated in 96-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well. Quantification of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) was performed by ELISA. Also, ELISA was performed with serum collected immediately after mice were euthanized to detect interferon γ (INF-γ) levels. These assays were performed according to BioLegend protocol. In brief, a 100-µL suspension of capture antibody was used to coat high-affinity protein-binding plates and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Four washes were completed using 300 µL of a wash solution consisting of PBS + 0.05% Tween-80, and all subsequent washes were performed in this manner. Incubation with a blocking solution for 1 h at RT occurred prior to 4 more washes. The plates were incubated for 2 h at RT with 100 µL of standards serially diluted 6 times per manufacturer instructions, or 100 µL of sample. After samples were washed, plates were then incubated with 100 µL of diluted biotinylated detection antibody for 1 h. Plates were again washed and incubated at RT for 30 min with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated avidin. Plates were washed 5 times for the last wash and incubated with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate for 20 min in the dark for fast color development. The chromatic reaction was stopped with 1 N hydrosulfuric acid. Plates were measured analyzed with a PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA) Victor2 plate reader. The concentrations were calculated by comparing the relative absorbance of samples at 450 nm, using standard concentrations to calculate the standard curve. To determine white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil counts and percentages from whole blood, samples were assayed using the hematological analyzer VetScan HM5 from ABAXIS (Union City, CA, USA).

2.8. Single-cell RNA sequencing

The liver mononuclear cells were washed in 10× buffer (1% bovine serum albumin + 1× PBS) and loaded onto the Chromium controller (10x Genomics) following the manufacturer’s procedure to target 3,000 cells per well. Samples were then process using the 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM single-cell 5′ reagent kit v2 (dual index) to generate scRNA-seq libraries. Using the NextSeq 550 sequencer (Illumina), we sequenced libraires with a depth of at least 25,000 reads per cell for each sample. Base call files generated from sequencing were analyzed with the 10x Genomics Cell Ranger pipeline (version 3.0.2) to generate FASTQ files, align reads to the mm10 genome, and generate the read count for each gene per individual cell. Cell counts were forced to 2,000 cells and reanalyzed using Loupe Browser (version 5.1). In order to determine cluster markers, differential gene expression was performed between the naive, ConA + vehicle (ConA + Veh), and ConA + FICZ samples.

2.9. Single-cell ATAC sequencing

As described above, live liver mononuclear cells were isolated. Nuclei from fresh cells were isolated according to the 10x Genomics protocol. In brief, cells were washed twice with 1 mL 0.04% bovine serum albumin in PBS. The cells (500,000) were transferred to a new tube for further lysis and centrifuged at 300 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 5 min and 4 °C to remove the supernatant. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of chilled lysis buffer for 5 min to lyse the cells. To stop the reaction, 1 mL of wash buffer was added, followed by centrifugation at 500 rcf for 5 min at 4 °C. Then, the pellet was resuspended in chilled diluted nuclei buffer aiming to target 200 nuclei for the naive group and 3,000 nuclei for the ConA-exposed groups. The final nuclei concentration was determined via a Bio-Rad TC20 Automated Cell Counter, and transposition was conducted. Samples were loaded onto the Chromium Controller targeting 2,000–3,000 cells per lane. The Chromium Next GEM single-cell ATAC Reagent kit v1.1 was used to process samples into single-cell ATAC libraries according to the manufacturer's protocol and sequenced on a NextSeq 550 instrument (Illumina). The 10x Genomics Cell Ranger ATAC pipeline (version 1.1.0) was used to generate data for downstream analysis using Loupe Browser (version 5.1) as described above.

2.10. Flow cytometry

Liver infiltrating mononuclear cells were counted using a TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad) and subsequently washed in staining buffer. TruStain FcX (BioLegend) incubation for 10 min at 4 °C was used to block Fc receptors. Samples were subsequently incubated with appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C (CD45-APC/Cy7, clone: 30-F11; F4/80-PE, clone: BM8; CD11b-FITC, clone: M1/70; CD68-BV421, clone: FA-11 from BioLegend). Analysis on a BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) FACSCelesta flow cytometer was performed after washing cells with staining buffer. Data analysis was performed with FlowJo (Ashland, OR, USA) v10 software.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The number of mice used in each experiment is depicted in the corresponding bar chart for Fig. 1. GraphPad Prism Version 9.0 for Mac (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test were utilized for multiple-group cross-comparative analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Fig. 1.

FICZ treatment reduces ConA-induced liver injury. C57BL/6 mice were injected with ConA followed by vehicle or FICZ 1 h later. After 24 h, livers were perfused, sectioned, and stained with H&E and serum from blood collected. (A) Histopathological analysis shows infiltrating cells in the liver of ConA + Veh mice when compared to the vehicle control and ConA + FICZ mice. N = 5(VEH), 5(ConA + VEH), 5(ConA + FICZ). (B) ALT levels in serum. N = 9(VEH), 7(ConA + VEH), 9(ConA + FICZ). (C) MCP-1 in serum, N = 8(VEH), 8(ConA + VEH), 6(ConA + FICZ). (D) TNFα in serum, N = 5(VEH), 4(ConA + VEH), 6(ConA + FICZ). (E) IFNγ in mononuclear cell culture supernatants. N = 14(VEH), 12(ConA + VEH), 14(ConA + FICZ). (F) Complete blood count showing total number and percentage of cells in plasma samples. N = 4(VEH), 4(ConA + VEH), 5(ConA + FICZ). Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Vertical bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. FICZ treatment reduces ConA-induced liver injury

To determine AhR-associated attenuation of liver injury in AIH, we used a model of immune-mediated liver injury induced by ConA. H&E staining of liver tissue collected at the end of the study demonstrated that ConA + Veh mice displayed substantial immune cell infiltration, which was reduced with FICZ treatment (Fig. 1A). FICZ treatment also significantly alleviated ConA-induced liver damage, as evidenced by a reduction in the circulating levels of ALT (Fig. 1B).

Next, we assessed the levels of the proinflammatory mediators MCP-1 (also known as CCL2), TNFα, and IFNγ during ConA-induced hepatitis. In the culture supernatants of mononuclear cells isolated from the livers, MCP-1 and TNFα were increased following ConA injection when compared to the vehicle controls while FICZ treatment significantly decreased their presence (Fig. 1C and D). An IFNγ ELISA on serum samples showed that IFNγ production was increased following ConA injection when compared to the vehicle controls (Fig. 1E), but FICZ did not significantly alter the IFNγ levels when compared to ConA + Veh group. These data suggested that FICZ reversed the effects of ConA-induced hepatitis which was associated with a decrease in inflammatory cytokine production such as MCP-1 and TNFα but not IFNγ.

To assess changes in the inflammatory profile, we performed complete blood counts on whole blood collected at the end of the study. We observed that ConA administration did not significantly alter the percentage or total number of WBCs, lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils when compared to the vehicle controls (Fig. 1F). Also, ConA + FICZ group did not show significant difference in these population of cells when compared to ConA + Veh group (Fig. 1F). However, the ConA + FICZ group showed a significant decrease in the percentage and numbers of lymphocytes, as well as an increase in monocyte and neutrophil percentage and numbers when compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 1F).

3.2. scRNA-seq reveals changes in liver mononuclear cell composition

To further characterize the changes induced upon ConA injection and subsequent FICZ treatment, scRNA-seq was performed on liver mononuclear cells isolated at the end of study. A total of 2,779 cells from the ConA + Veh sample, 2,086 cells from the naive sample, and 2,555 cells from the ConA + FICZ sample were captured and sequenced. Prior to downstream analysis, the cell count was forced to 2,000 cells per group to normalize the comparisons. Principal component analysis was used to generate t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots to visual multiple dimension data. Annotating each sample by color revealed several immune cell clusters (Fig. 2A). When annotating each cluster by color, we observed unique clusters in the ConA-treated mice compared to the naive mice, and FICZ treatment caused significant differences (Fig. 2B). Notably, we observed CD55+ B cells in the naive group (49.9%), which were absent in the ConA + Veh group (0.35%), although this finding was partially reversed following FICZ treatment (7.15%) (Fig. 2C). Naive T cells decreased in the ConA + Veh group when compared to the Veh group while the ConA + FICZ group showed a slight increase in naive T cells when compared to ConA + Veh group (Table 1). Also, the ConA + Veh group had NKT cells, CD4+/CD8+ T cells, activated T cells, and memory CD8 T cells, which were decreased or not found in the naive group and markedly decreased in the ConA + FICZ group (Table 1). FICZ increased the percentage of Kupffer cells and neutrophils (Fig. 2B). These data show that ConA injection, as well as AhR activation, can alter changes in immune cell populations in the liver.

Fig. 2.

scRNA-seq reveals changes in liver mononuclear cell composition. C57BL/6 mice were injected with ConA followed by vehicle or FICZ as described in Fig. 1. Liver mononuclear cells were isolated from the livers of 3 mice pooled per group and scRNA-seq was performed. (A) t-SNE plot with each sample categorized by color and main clusters labeled. (B) t-SNE plot separated by sample group and colored to show identified cell clusters. (C) Pie chart showing the percentage of cells contained in each t-SNE cluster.

Table 1.

Percentage of cells in each cluster from scRNA-seq analysis.

| Naïve, % | ConA + Veh, % | ConA + FICZ, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD55+ B cells | 49.90 | 0.35 | 7.15 |

| NKT cells | 4.10 | 16.00 | 11.40 |

| Mature B cells | 3.80 | 31.40 | 27.35 |

| Kupffer cells | 4.85 | 9.55 | 10.40 |

| T cells (CD4+ or CD8+) | 0.65 | 12.00 | 10.35 |

| Naive T cells | 14.55 | 1.30 | 3.15 |

| NK cells | 14.40 | 0.55 | 2.30 |

| Neutrophils | 1.05 | 2.85 | 9.40 |

| Naive γδ T cells | 0.40 | 6.00 | 6.40 |

| Activated T cells | 0.80 | 8.05 | 1.95 |

| Lymphatic endothelial cells | 2.85 | 4.95 | 2.70 |

| Memory CD8 T cells | 0.50 | 6.40 | 3.15 |

| Hepatocytes | 2.15 | 0.60 | 4.30 |

3.3. Significantly dysregulated genes in mature B-cell, lymphatic endothelial cell, and memory CD8+ T-cell clusters

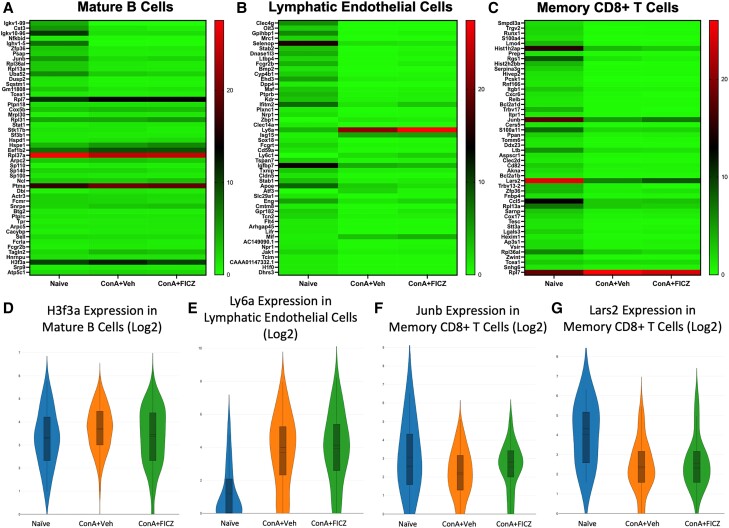

Fifty differentially expressed genes with significant P values per treatment group for each cluster were visualized in a heatmap (Fig. 3A–C). Genes of interest and their functions are shown in Table 2. In the mature B-cell cluster, the gene encoding for histone 3, family 3A (H3f3a) was upregulated upon ConA injection and downregulated in the FICZ-exposed group (Fig. 3D). Upregulation of this gene has been shown to correlate with thyroid cancer progression via increased proliferation and metastasis.23 Lymphocyte antigen complex, locus A (Ly6a), which is also known as stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1), has been shown to be upregulated in response to interferon α (IFNα) and suggested as a mediator of hematopoietic stem cell proliferation.24 In the lymphatic endothelial cell cluster, Ly6a was markedly upregulated in response to ConA, and FICZ treatment further upregulated the expression (naive mean = 1.178, ConA + Veh mean = 3.680, ConA + FICZ mean = 3.928) (Fig. 3E). In the memory CD8+ T-cell cluster, Junb, a critical transcription factor for macrophage activation,26 was downregulated in the ConA + Veh group, but FICZ treatment prevented downregulation to this level (naive mean = 3.072, ConA + Veh mean = 2.229, ConA + FICZ mean = 2.538) (Fig. 3C). Leucyl-tRNA synthetase 2 (Lars2) is a mitochondrial enzyme that has been linked to proapoptotic gene processing and shown to be downregulated in primary carcinoma samples.27,40 Lars2 was markedly downregulated in ConA-exposed groups within the memory CD8+ T-cell cluster (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Significantly dysregulated genes in mature B-cell, lymphatic endothelial cell, and memory CD8+ T-cell clusters. Heatmaps consisting of the top 50 differential genes per treatment were generated. Heatmaps of differentially expressed genes from (A) mature B cells, (B) lymphatic endothelial cells, and (C) memory CD8+ T-cell clusters. (D–G) Violin plot of Log2 expression of target gene.

Table 2.

Associated functions of significantly dysregulated genes of interest.

| Gene | Associated Function |

|---|---|

| H3f3a | Thyroid cancer progression23 |

| Ly6a | Mediator of hematopoietic stem cell proliferation24 |

| Junb | Macrophage activation25 |

| Lars2 | Catalyzes reactions in mitochondrial-specific protein synthesis26 |

| Gzma | Pyroptosis27 |

| Srgn | Cytokine and chemokine secretion28 |

| Malat1 | Associated with interferon production29 |

| Ccl4 | Monocyte and neutrophil chemotaxis30 |

| Klf2 | Negative regulator of T cell proliferation31 |

| Ccl5 | Effector T and memory T cell recruitment32 |

| Hspd1 | T and B-cell activation, interferon and interleukin production, cell invasion, and Treg induction33–35 |

| Cxcl2 | Neutrophil recruitment36 |

| Lcn2 | Mediator of neutrophil and hepatic macrophage crosstalk37 |

| Ptma | Chromatin activity, apoptosis, and cellular proliferation38 |

| Rpl37a | Induces G2 cell cycle arrest39 |

3.4. Transcriptomic analysis of NK and NKT cell clusters

Within the NKT cell cluster, granzyme A (Gzma), serglycin (Srgn), and the long-chain noncoding RNA metastasis-related lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1) were identified as significantly dysregulated genes of interest (Fig. 4A). Gzma was upregulated in both ConA-exposed groups, supporting its role in mediating pyroptosis.28 Srgn, a proteoglycan associated with cytokine and chemokine secretion,31 was upregulated upon ConA injection, but this upregulation was hampered in the FICZ-treated group (Fig. 4D). FICZ treatment downregulated the expression of Malat1 in NKT cells (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Transcriptomic analysis of NK and NKT cell clusters. Heatmaps consisting of the top 50 differential genes per treatment were generated. Heatmaps of differentially expressed genes from (A) NKT and (B) NK cells clusters. (C–G) Violin plot of Log2 expression of target gene.

C-C motif chemokine ligand 4 (Ccl4) and Junb were identified as significantly dysregulated genes in the NK cell cluster (Fig. 4B). Ccl4 was upregulated in both ConA-exposed groups (Fig. 4F). Junb was downregulated in the ConA + Veh group but upregulated upon FICZ exposure (Fig. 4G).

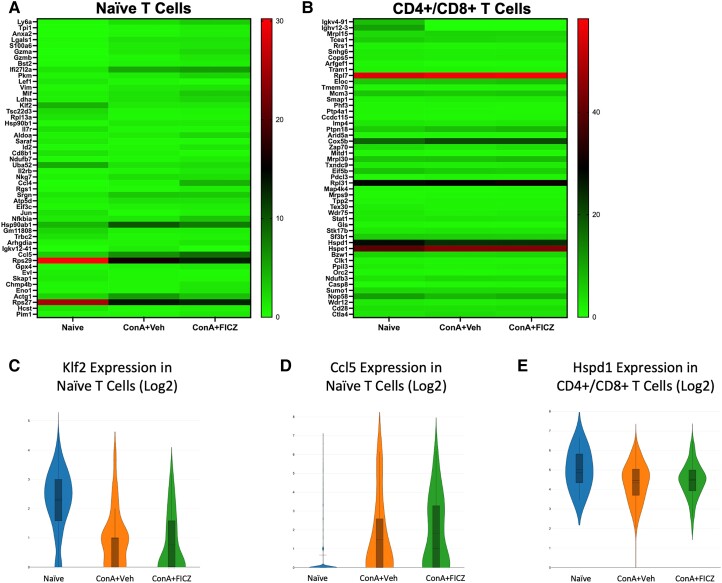

3.5. Klf2, Ccl5, and Hspd1 were identified as genes of interest in naive and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell clusters

Kruppel-like factor 2 (Klf2), a negative regulator of T-cell proliferation,41 and C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (Ccl5) were identified in the naive T-cell clusters as target genes (Fig. 5A). FICZ treatment partially recovered the decrease in Klf2 expression induced by ConA exposure (Fig. 5C), supporting FICZ's ability to limit T-cell proliferation in this model. Ccl5 was also drastically upregulated in both ConA-exposed groups in this cluster (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Klf2, Ccl5, and Hspd1 were identified as genes of interest in naive and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell clusters. Heatmaps consisting of the top 50 differential genes per treatment were generated. Heatmaps of differentially expressed genes from (A) naive T-cell and (B) CD4+/CD8+ T-cell clusters. (C–E) Violin plot of Log2 expression of target gene.

Within the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell clusters, heat shock protein family D member 1 (Hspd1) was identified as a gene of interest (Fig. 5B). Hspd1 has been shown to reduce immune inflammation through toll-like receptor 2 signaling.36 Hspd1 was downregulated in both ConA-exposed groups, although to a lesser extent with FICZ treatment (naive mean = 5.013, ConA + Veh mean = 4.336, ConA + FICZ mean = 4.454) (Fig. 5E).

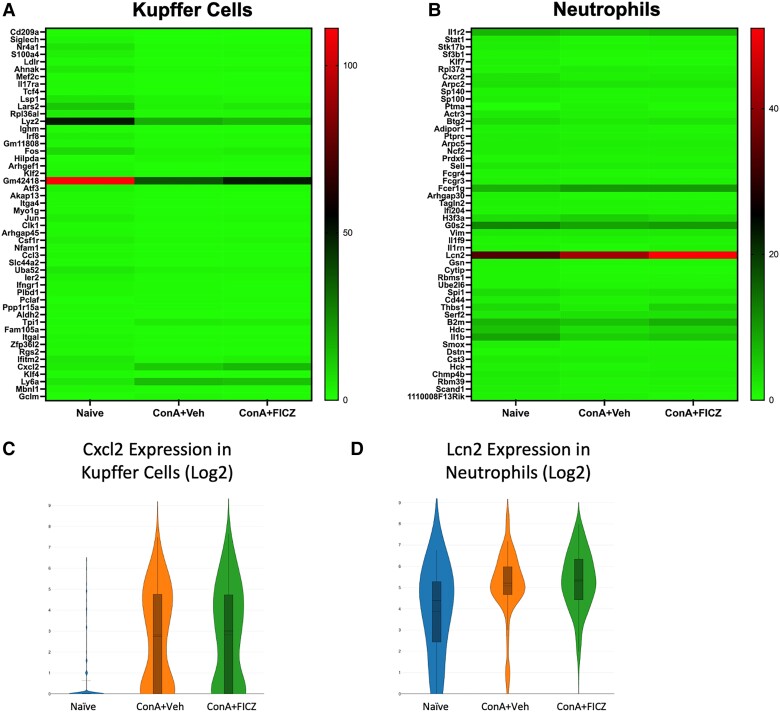

3.6. Analysis of gene dysregulation in Kupffer cells and neutrophils

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (Cxcl2) was identified as a gene of interest in the Kupffer cell cluster (Fig. 6A) while lipocalin 2 (Lcn2) was identified in the neutrophil cluster (Fig. 6B). CXCL2, a chemotaxis factor associated with neutrophil recruitment,37 was drastically upregulated in both ConA-exposed groups (Fig. 6C), supporting an increased infiltration of neutrophils. Lcn2 was also drastically upregulated in neutrophils in both ConA-exposed groups (Fig. 6D) and has been shown to be increased during hepatic injury.38 This gene also has been implicated as a mediator of neutrophil and hepatic macrophage crosstalk,38 thereby supporting the importance of the myeloid compartment in ConA-induced hepatitis and AhR activation by FICZ.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of gene dysregulation in Kupffer cells and neutrophils. Heatmaps consisting of the top 50 differential genes per treatment were generated. Heatmaps of differentially expressed genes from (A) Kupffer cell and (B) neutrophil clusters. (C, D) Violin plot of Log2 expression of target gene.

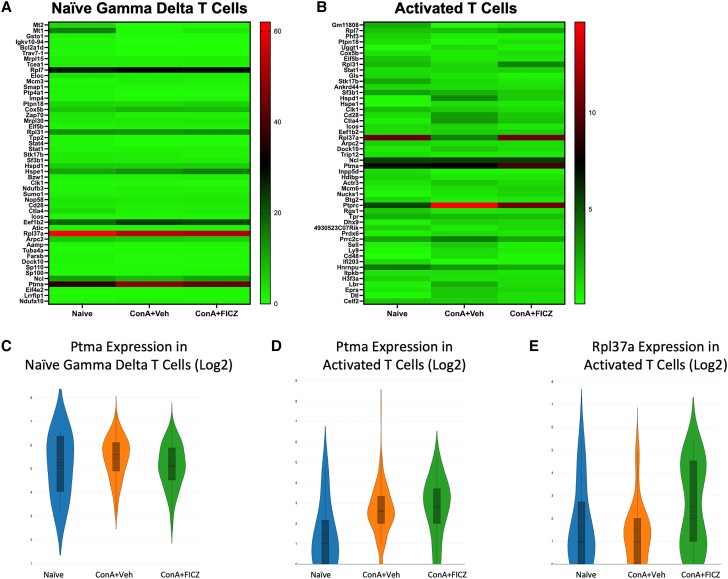

3.7. Ptma and Rpl37a as significantly dysregulated genes in naive γδ and activated T-cell clusters

Prothymosin alpha (Ptma) was identified in both the naive γδ T-cell and activated T-cell clusters as a significantly dysregulated gene of interest (Fig. 7A and B). PTMA was originally isolated from the thymus and has been shown to act as an immunomodulatory protein.42,43 It was upregulated upon ConA injection and downregulated with FICZ treatment in the naive γδ T-cell cluster (naive mean = 5.136, ConA + Veh mean = 5.600, ConA + FICZ mean = 5.106) (Fig. 7C), while contrarily, FICZ further upregulated its expression in the activated T-cell cluster (naive mean = 1.428, ConA + Veh mean = 2.619, ConA + FICZ mean = 2.800) (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Ptma and Rpl37a as significantly dysregulated genes in naive γδ and activated T-cell clusters. Heatmaps consisting of the top 50 differential genes per treatment were generated. Heatmaps of differentially expressed genes from (A) naive γδ T cells and (B) activated T-cell clusters. (C–E) Violin plot of Log2 expression of target gene.

Ribosomal protein L37a (Rpl37a) was also considered a gene of interest in the activated T-cell cluster due to its ability to induce G2 cell cycle arrest.44 High expression of this gene was observed upon FICZ treatment, again supporting the ability of FICZ to limit the proliferation of activated T cells.

3.8. scATAC-seq provides insights into immune cell chromatin accessibility alterations

scATAC-seq was performed on nuclei isolated from liver-infiltrating mononuclear cells to examine the changes in chromatin accessibility induced upon ConA challenge and subsequent FICZ treatment. Sequenced samples were forced to 700 cells to normalize comparisons. Each sample is represented by color in the tSNE plot illustrated in the text (Fig. 8A). ConA-treated mice again in comparison to the naive group showed unique immune cell clusters, and there were significant differences observed following FICZ treatment (Fig. 8B). Specifically, we observed an increase in exhausted CD8+ T cells expressing Tox2 and Bcl6 in the ConA + Veh group as well as NK cells, although treatment with FICZ reduced the prevalence of these cells (Fig. 8B). We also noticed an increase in Adgre1 (F4/80)–expressing Kupffer cells in the FICZ-treated group (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

scATAC-seq provides insights into immune cell chromatin accessibility alterations. C57BL/6 mice were injected with ConA followed by vehicle or FICZ, as described in Fig. 1. Liver mononuclear cells were isolated and nuclei isolation was performed, followed by transposition from the livers of 3 mice pooled per group. The Chromium Next GEM single-cell ATAC Reagent kit v1.1 was used to process samples into single-cell ATAC libraries according to the manufacturer's protocol and sequenced on a NextSeq 550 instrument (Illumina). The 10x Genomics Cell Ranger ATAC pipeline (version 1.1.0) was used to generate data for downstream analysis using Loupe Browser (version 5.1) as described in the Methods. (A) t-SNE plot with each sample categorized by color. (B) t-SNE plot separated by sample group and colored to show identified cell clusters. (C, D) Chromatin accessibility in promotor regions, showing cells with a peak at the CD3e promoter and Adgre1 promoter in the 3 groups.

When exploring promoter accessibility, we observed an overall increase in the proportion of cells with a peak at the CD3e promoter upon ConA exposure that was limited with FICZ treatment (Fig. 8C). Interestingly, upon exploring the Adgre1 promoter, there was an increase in the proportion of cells with a peak within the ConA + Veh group, and FICZ treatment further increased the proportion of cells (Fig. 8D). Together, these data support FICZ's ability to limit T-cell infiltration in this model, while suggesting a more prominent role for F4/80+ Kupffer cells.

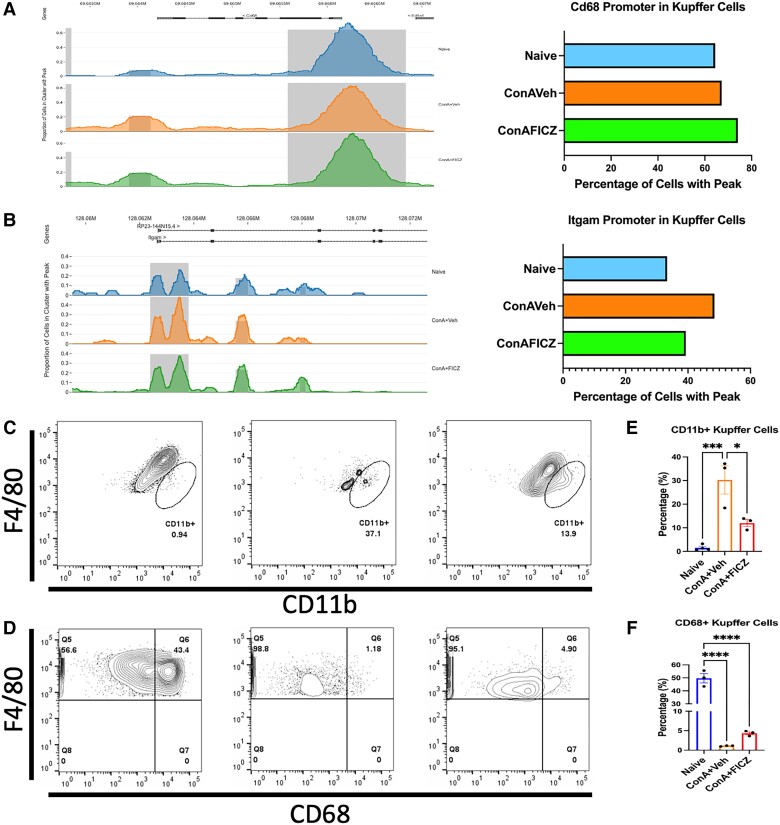

3.9. FICZ limits infiltration of CD11b+ Kupffer cells

It is generally accepted that there are 2 main subsets of Kupffer cells: a resident, immunotolerant, phagocytosing CD68+ subset and a cytokine-producing CD11b+ subset derived from circulating monocytes.45,46 We explored the Kupffer cell cluster within our scATAC-seq data and noticed an increase in chromatin accessibility with ConA exposure and FICZ treatment in the Cd68 promoter (Fig. 9A). However, analysis of the Itgam (CD11b) promoter within the Kupffer cell cluster showed an increase of the percentage of cells with a peak in this region in the ConA + Veh group, while FICZ limited this effect (Fig. 9B). We then performed flow cytometry on liver mononuclear cells to characterize the F4/80 population. We again saw that there was a significant increase in the percentage of F4/80 cells also positive for CD11b upon ConA challenge and that FICZ significantly decreased this population (Fig. 9C and E). We also found that ConA significantly decreased the percentage of F4/80+ CD68+ cells in the liver and that FICZ partially protected this population (Fig. 9D and 9F). Thus, FICZ reduced the severity of ConA-induced liver injury by limiting the infiltration of CD11b+ Kupffer cells induced upon ConA.

Fig. 9.

FICZ limits infiltration of CD11b+ Kupffer cells. Using Loupe Browser, coverage plots of accessibility at the (A) Cd68 promoter and (B) Itgam promoter were created and displayed as percentages of cells with peaks in a bar graph. Representative flow plots of (C) F4/80+CD11b+ cells and (D) F4/80+CD68+ cells. Corresponding bar graphs displaying the percentage of F4/80+ cells positive for (E) CD11b or (F) CD68. N = 3(VEH), 3(ConA + VEH), 3(ConA + FICZ). Significance was determined by 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Vertical bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

The murine model of ConA-induced, immune cell–mediated liver injury mimics autoimmune hepatitis in humans in that it mirrors the multicellular mechanisms involved.10,11 Traditionally believed to be a CD4+ T helper cell activated model, more recent studies have shown that in addition to interacting with major histocompatibility complex class II molecules, ConA also engages with the mannose receptor present on a variety of other liver immune cells, including Kupffer cells and neutrophils.10,47 AhR activation can suppress inflammation through a variety of mechanisms, including suppression of proinflammatory cytokines secreted by lymphocytes or cells within the myeloid compartment.48 FICZ binds AhR at the highest affinity, although its effects have been conflicting in that published data show FICZ both promoting and limiting inflammation.21,49–52 This study demonstrates that FICZ attenuates ConA-induced hepatitis, as evidenced by a decrease in ALT and proinflammatory cytokine secretion. To that end, we explored potential mechanisms through which it enacts these effects.

Through scRNA-seq, we observed decreases in T-cell subsets with FICZ treatment and increases in Kupffer cells and neutrophils. While there are studies focused on FICZ's ability to induce proinflammatory Th17 cells in various inflammatory models,15,19,50,52 it is well understood that these effects are both time and dose dependent.53 Thus, our results could potentially be due to how rapidly disease manifestation occurs in this model as well as our treatment time of 1 h after ConA injection. Additionally, it has been shown that FICZ treatment can lead to the stimulation of macrophages expressing immunosuppressive properties through modulation of microRNA-142a.54 Because we observed increases in Kupffer cells, epigenetic mechanisms of regulation should be explored to determine if a similar mechanism is utilized in this model.

In our scRNA-seq data, we observed that naive mice had significant levels of CD55+ B cells in the liver while ConA treatment led to marked decrease in these cells and FICZ exposure partially reversed this. Surprisingly, another high-affinity AhR ligand, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, was unable to restore this population of CD55+ B cells initially depleted by ConA (data not shown). CD55 (also known as decay-accelerating factor) is involved in complement activation, and its expression on T cells is involved in T-cell activation, response, and function.55 Thus, the CD55-expressing B cells may play a role in the regulation of the immune response in the liver, which needs further study.

We used scATAC-seq to determine the underlying mechanisms by which FICZ treatment induces Kupffer cell counts and concluded that chromatin accessibility is altered in our treatment groups in promoters involved in Kupffer cell phenotypes. Kupffer cells are characterized as F4/80+ cells that express CD11b or CD68 and have been shown to be critical in murine acute liver injury models.45,47 Decreases in the cytokine-producing subset of CD11b+ Kupffer cells by FICZ support the reduced secretion and/or circulation of MIP-1 and TNFα as well as attenuation of liver injury as TNFα is critical in disease pathogenesis in this model.9 It is worth noting that FICZ was not able to decrease the levels of IFNγ. It is well known that AhR activation regulates macrophage polarization and that a variety of liver immune cells, including Kupffer cells, express AhR.11,18,54,56 While this supports our findings of AhR activation by FICZ influencing Kupffer cell behavior, a limitation of this study is that the effects of AhR-specific activation in other liver cells, including endothelial cells, were not explored. These studies should be conducted in order to determine if AhR activation in other hepatocytes plays a role in disease attenuation.

Resident Kupffer cells have been shown to produce CXCL2 in the mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.57 Neutrophils egress from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood and to sites of inflammation driven by chemokine receptors CXCR2 expressed on neutrophils and the CXCR2 ligands such as CXCL1 and CXCL2.58 ConA administration led to significant induction of CXCL2 by Kupffer cells, thereby suggesting that these cells may play a role in neutrophil infiltration in the liver after ConA exposure. However, after ConA + FICZ treatment, the CXCL2 expression in Kupffer cells did not change significantly.

Additionally, lipocalin 2 (LCN2), also called neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, is a secreted glycoprotein involved in transportation of small lipophilic molecules.59 Recent studies have shown that LCN2 acts as a chemoattracting factor for the recruitment of neutrophils, which in turn produce more proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including LCN2, which drives the innate immune response.60 We found that LCN2 was markedly upregulated in neutrophils following ConA exposure while FICZ caused an additional minor increase. These data suggested that LCN2 produced by neutrophils during ConA-induced hepatitis may play a role in liver inflammation and that FICZ-mediated attenuation of hepatitis is independent of this pathway.

Prothymosin alpha (PTMA), originally isolated from the thymus, has been shown to act as an immunomodulatory protein.43 PTMA is known to regulate a variety of immune functions.43 For example, PTMA can stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation and cytotoxicity, as well as enhance maturation of dendritic cells.43 In the current study, we noted that PTMA was significantly induced in γδT cells and activated T cells upon ConA exposure. It was downregulated with FICZ treatment in the γδT cells, while contrarily, FICZ further upregulated its expression in the activated T cells. Thus, the role of PTMA in hepatic inflammation can be predicted, and it was likely not involved in FICZ-mediated attenuation of hepatitis.

One of the limitations of the current study is that we tested the effect of FICZ in only 1 model of liver injury caused by ConA, a T-cell mitogen. Thus, these findings cannot be used to generalize the concept that FICZ or AhR activation can attenuate inflammation in all forms of liver injury. Further studies are necessary to investigate if FICZ can attenuate liver injury in other models of autoimmune hepatitis.

Collectively, the current study demonstrates that FICZ has the ability to attenuate ConA-induced liver injury through both reduced CD3+ T-cell infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine-producing F4/80+ CD11b+ Kupffer cells. scATAC-seq provided critical insights into chromatin accessibility changes at these gene promoters, and in combination with scRNA-seq analysis, a more complete picture of the changes induced upon AhR activation by FICZ in this model was provided. Thus, with the emergence of more comprehensive studies involving high-throughput sequencing techniques such as these, the potential of AhR targeting is supported as a novel therapeutic.

Contributor Information

Alkeiver S Cannon, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Bryan L Holloman, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Kiesha Wilson, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Kathryn Miranda, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Prakash S Nagarkatti, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Mitzi Nagarkatti, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 6439 Garners Ferry Road, Columbia, SC 29209, United States.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.S.C., P.S.N., and M.N. Experimentation and data acquisition: A.S.C., B.L.H., K.W., and K.M. Validation: A.S.C. Formal analysis: A.S.C. and K.W. Resources: P.S.N. and M.N. Writing—original draft: A.S.C. Writing—review and editing: A.S.C., P.S.N., and M.N. Visualization: A.S.C. Supervision: P.S.N. and M.N. Funding acquisition: P.S.N. and M.N.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01ES019313, R01MH094755, R01AI123947, R01AI129788, P01AT003961, P20GM103641, R01AT006888, and 3R01AI123947-04S1 (P.S.N. and M.N.).

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Carolina. All mice were housed in the University of South Carolina School of Medicine AAALAC-accredited animal facility.

References

- 1. Cooper GS, Stroehla BC. The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2003:2(3):119–125. 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00006-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Invernizzi P, Mackay IR. Autoimmune liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008:14(21):3290–3291. 10.3748/wjg.14.3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francque S, Vonghia L, Ramon A, Michielsen P. Epidemiology and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatic Med Evid Res. 2012:4:1–10. 10.2147/HMER.S16321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El-Masry M, Gilbert CP, Saab S. Recurrence of non-viral liver disease after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2011:31(3):291–302. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006:354(1):54–66. 10.1056/NEJMra050408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanaka A. Autoimmune hepatitis: 2019 update. Gut Liver. 2020:14(4):430–438. 10.5009/gnl19261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Czaja AJ, Bianchi FB, Carpenter HA, Krawitt EL, Lohse AW, Manns MP, McFarlane IG, Mieli-Vergani G, Toda G, Vergani D, et al. Treatment challenges and investigational opportunities in autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005:41(1):207–215. 10.1002/hep.20539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen D, McKallip RJ, Zeytun A, Do Y, Lombard C, Robertson JL, Mak TW, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. CD44-deficient mice exhibit enhanced hepatitis after concanavalin A injection: evidence for involvement of CD44 in activation-induced cell death. J Immunol. 2001:166(10):5889–5897. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heymann F, Hamesch K, Weiskirchen R, Tacke F. The concanavalin A model of acute hepatitis in mice. Lab Anim. 2015:49(1_suppl):12–20. 10.1177/0023677215572841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu Y, Hao H, Hou T. Concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis model in mice: mechanisms and future outlook. Open Life Sci. 2022:17(1):91–101. 10.1515/biol-2022-0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cannon AS, Holloman BL, Wilson K, Miranda K, Dopkins N, Nagarakatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Ahr activation leads to attenuation of murine autoimmune hepatitis: single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals unique immune cell phenotypes and gene expression changes in the liver. Front Immunol. 2022:13:899609. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.899609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bock KW. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) functions: balancing opposing processes including inflammatory reactions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020:178:114093. 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Negishi T, Kato Y, Ooneda O, Mimura J, Takada T, Mochizuki H, Yamamoto M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Furusako S. Effects of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling on the modulation of Th1/Th2 balance. J Immunol. 2005:175(11):7348–7356. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al-Ghezi ZZ, Singh N, Mehrpouya-Bahrami P, Busbee PB, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Ahr activation by TCDD (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) attenuates pertussis toxin-induced inflammatory responses by differential regulation of tregs and Th17 cells through specific targeting by microRNA. Front Microbiol. 2019:10:2349. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quintana FJ, Basso AS, Iglesias AH, Korn T, Farez MF, Bettelli E, Caccamo M, Oukka M, Weiner HL. Control of Treg and TH17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 2008:453(7191):65–71. 10.1038/nature06880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Busbee PB, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Natural indoles, indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM), attenuate staphylococcal enterotoxin B-mediated liver injury by downregulating miR-31 expression and promoting caspase-2-mediated apoptosis. PLoS One. 2015:10(2):e0118506. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kummari E, Rushing E, Nicaise A, McDonald A, Kaplan BLF. TCDD attenuates EAE through induction of FasL on B cells and inhibition of IgG production. Toxicology. 2021:448:152646. 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abron JD, Singh NP, Mishra MK, Price RL, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS, Singh UP. An endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand, ITE, induces regulatory T cells and ameliorates experimental colitis. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018:315(2):G220–G230. 10.1152/ajpgi.00413.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh NP, Singh UP, Singh B, Price RL, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) leads to reciprocal epigenetic regulation of FoxP3 and IL-17 expression and amelioration of experimental colitis. PLoS One. 2011:6(8):e23522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rouse M, Singh NP, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Indoles mitigate the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by induction of reciprocal differentiation of regulatory T cells and Th17 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013:169(6):1305–1321. 10.1111/bph.12205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rannug A. 6-Formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole, a potent ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor produced both endogenously and by microorganisms, can either promote or restrain inflammatory responses. Front Toxicol. 2022:4:775010. 10.3389/ftox.2022.775010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hegde VL, Hegde S, Cravatt BF, Hofseth LJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Attenuation of experimental autoimmune hepatitis by exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids: involvement of regulatory T cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008:74(1):20–33. 10.1124/mol.108.047035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hegde VL, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in amelioration of experimental autoimmune hepatitis following activation of TRPV1 receptors by cannabidiol. PLoS One. 2011:6(4):e18281. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fang J, Zhu JM, Dai HL, He LM, Kong L. MicroRNA-198 inhibits metastasis of thyroid cancer by targeting H3F3A. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020:24(23):12232–12240. 10.26355/eurrev_202012_24015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Essers MAG, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, Trumpp A. IFNα activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009:458(7240):904–908. 10.1038/nature07815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fontana MF, Baccarella A, Pancholi N, Pufall MA, Herbert DR, Kim CC. JUNB is a key transcriptional modulator of macrophage activation. J Immunol. 2015:194(1):177–186. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou W, Feng X, Li H, Wang L, Zhu B, Liu W, Zhao M, Yao K, Ren C. Inactivation of LARS2, located at the commonly deleted region 3p21.3, by both epigenetic and genetic mechanisms in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2009:41(1):54–62. 10.1093/abbs/gmn006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granzyme A from cytotoxic lymphocytes cleaves GSDMB to trigger pyroptosis in target cells. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aaz7548?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed& [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Liu W, Wang Z, Liu L, Yang Z, Liu S, Ma Z, Liu Y, Ma Y, Zhang L, Zhang X, et al. LncRNA Malat1 inhibition of TDP43 cleavage suppresses IRF3-initiated antiviral innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020:117(38):23695–23706. 10.1073/pnas.2003932117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gruber CN, Patel RS, Trachtman R, Lepow L, Amanat F, Krammer F, Wilson KM, Onel K, Geanon D, Tuballes K, et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell. 2020:183(4):982–995.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kolset SO, Pejler G. Serglycin: a structural and functional chameleon with wide impact on immune cells. J Immunol. 2011:187(10):4927–4933. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seo W, Shimizu K, Kojo S, Okeke A, Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Fujii S-I, Taniuchi I. Runx-mediated regulation of CCL5 via antagonizing two enhancers influences immune cell function and anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 2020:11(1):1562. 10.1038/s41467-020-15375-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SK, Kim K, Ryu JW, Ryu T-Y, Lim JH, Oh J-H, Min J-K, Jung C-R, Hamamoto R, Son M-Y, et al. The novel prognostic marker, EHMT2, is involved in cell proliferation via HSPD1 regulation in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2018:54(1):65–76. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kang BH, Shu CW, Chao JK, Lee C-H, Fu T-Y, Liou H-H, Ger L-P, Liu P-F. HSPD1 repressed E-cadherin expression to promote cell invasion and migration for poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019:9(1):8932. 10.1038/s41598-019-45489-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Kleer I, Vercoulen Y, Klein M, Meerding J, Albani S, van der Zee R, Sawitzki B, Hamann A, Kuis W, Prakken B. CD30 discriminates heat shock protein 60-induced FOXP3 + CD4+ T cells with a regulatory phenotype. J Immunol. 2010:185(4):2071–2079. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zanin-Zhorov A, Bruck R, Tal G, Oren S, Aeed H, Hershkoviz R, Cohen IR, Lider O. Heat shock protein 60 inhibits Th1-mediated hepatitis model via innate regulation of Th1/Th2 transcription factors and cytokines. J Immunol. 2005:174(6):3227–3236. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Faget J, Groeneveld S, Boivin G, Sankar M, Zangger N, Garcia M, Guex N, Zlobec I, Steiner L, Piersigilli A, et al. Neutrophils and snail orchestrate the establishment of a pro-tumor microenvironment in lung cancer. Cell Rep. 2017:21(11):3190–3204. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ye D, Yang K, Zang S, Lin Z, Chau H-T, Wang Y, Zhang J, Shi J, Xu A, Lin S, et al. Lipocalin-2 mediates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by promoting neutrophil-macrophage crosstalk via the induction of CXCR2. J Hepatol. 2016:65(5):988–997. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daftuar L, Zhu Y, Jacq X, Prives C. Ribosomal proteins RPL37, RPS15 and RPS20 regulate the Mdm2-p53-MdmX network. PLoS One. 2013:8(7):e68667. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lynch SJ, Zavadil J, Pellicer A. In TCR-stimulated T-cells, N-ras regulates specific genes and signal transduction pathways. PLoS One. 2013:8(6):e63193. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. García-Palma L, Horn S, Haag F, Diessenbacher P, Streichert T, Mayr GW, Jücker M. Up-regulation of the T cell quiescence factor KLF2 in a leukaemic T-cell line after expression of the inositol 5′-phosphatase SHIP-1. Br J Haematol. 2005:131(5):628–631. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barbeito P, Sarandeses CS, Díaz-Jullien C, Muras J, Covelo G, Moreira D, Freire-Cobo C, Freire M. Prothymosin α interacts with SET, ANP32A and ANP32B and other cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins in proliferating cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017:635:74–86. 10.1016/j.abb.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Samara P, Ioannou K, Tsitsilonis OE. Prothymosin alpha and immune responses: are we close to potential clinical applications? Vitam Horm. 2016:102:179–207. 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhou X, Liao WJ, Liao JM, Liao P, Lu H. Ribosomal proteins: functions beyond the ribosome. J Mol Cell Biol. 2015:7(2):92–104. 10.1093/jmcb/mjv014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kinoshita M, Uchida T, Sato A, Nakashima M, Nakashima H, Shono S, Habu Y, Miyazaki H, Hiroi S, Seki S. Characterization of two F4/80-positive Kupffer cell subsets by their function and phenotype in mice. J Hepatol. 2010:53(5):903–910. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Okamoto N, Ohama H, Matsui M, Fukunishi S, Higuchi K, Asai A. Hepatic F4/80+CD11b+CD68– cells influence the antibacterial response in irradiated mice with sepsis by Enterococcus faecalis. J Leukoc Biol. 2021:109(5):943–952. 10.1002/JLB.4A0820-550RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsutsui H, Nishiguchi S. Importance of kupffer cells in the development of acute liver injuries in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2014:15(5):7711–7730. 10.3390/ijms15057711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cannon AS, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Targeting AhR as a novel therapeutic modality against inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022:23(1):288. 10.3390/ijms23010288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang J, Cai X, Ou Y, Fan L, Zhou Y, Wang Y. Protective roles of FICZ and aryl hydrocarbon receptor axis on alveolar bone loss and inflammation in experimental periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2019:46(9):882–893. 10.1111/jcpe.13166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li X, Luck ME, Hammer AM, Cannon AR, Choudhry MA. 6-Formylindolo (3, 2-b) carbazole (FICZ)–mediated protection of gut barrier is dependent on T cells in a mouse model of alcohol combined with burn injury. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020:1866(11):165901. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abdulla OA, Neamah W, Sultan M, Alghetaa HK, Singh N, Busbee PB, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti P. The ability of AhR ligands to attenuate delayed type hypersensitivity reaction is associated with alterations in the gut microbiota. Front Immunol. 2021:12:2505. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.684727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Abdulla OA, Neamah W, Sultan M, Chatterjee S, Singh N, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti P. Ahr ligands differentially regulate miRNA-132 which targets HMGB1 and to control the differentiation of tregs and Th-17 cells during delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Front Immunol. 2021:12:635903. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Farmahin R, Crump D, O’Brien JM, Jones SP, Kennedy SW. Time-dependent transcriptomic and biochemical responses of 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ) and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) are explained by AHR activation time. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016:115:134–143. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang X, Liu H, Ye T, Duan C, Lv P, Wu X, Liu J, Jiang K, Lu H, Yang H, et al. Ahr activation attenuates calcium oxalate nephrocalcinosis by diminishing M1 macrophage polarization and promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Theranostics. 2020:10(26):12011–12025. 10.7150/thno.51144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nyambuya TM, Dludla PV, Mxinwa V, Nkambule BB. The pleotropic effects of fluvastatin on complement-mediated T-cell activation in hypercholesterolemia. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021:143:112224. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yan J, Tung HC, Li S, Niu Y, Garbacz WG, Lu P, Bi Y, Li Y, He J, Xu M, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling prevents activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2019:157(3):793–806.e14. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Han YH, Choi H, Kim HJ, Lee MO. Chemotactic cytokines secreted from Kupffer cells contribute to the sex-dependent susceptibility to non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. Life Sci. 2022:306:120846. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sadik CD, Kim ND, Luster AD. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011:32(10):452–460. 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abella V, Scotece M, Conde J, Gómez R, Lois A, Pino J, Gómez-Reino JJ, Lago F, Mobasheri A, Gualillo O. The potential of lipocalin-2/NGAL as biomarker for inflammatory and metabolic diseases. Biomarkers. 2015:20(8):565–571. 10.3109/1354750X.2015.1123354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Guardado S, Ojeda-Juárez D, Kaul M, Nordgren TM. Comprehensive review of lipocalin 2-mediated effects in lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021:321(4):L726–L733. 10.1152/ajplung.00080.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]